The portrayal of bears in Russian folklore and heraldry and their use as a symbol of national pride.

By Dr. Anne M. Platoff

Librarian

UCSB Library

University of California, Santa Barbara

Introduction

Viewers of international sporting events have become accustomed to seeing informal sporting flags waved by citizens of various countries. The most familiar of these flags, of course, are the “Boxing Kangaroo” flag used to represent Australia and the “Fighting Kiwi” flag used by fans from New Zealand. Both of these flags have become common at the Olympic Games when athletes from those nations compete. Recently a new flag of this type has been displayed at international soccer matches and the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics.

Unlike the Kangaroo and Kiwi flags, this new flag has been constructed using a defaced national flag, the Russian tricolor flag of white, blue, and red horizontal stripes, readopted as the flag of the Russian Federation after the breakup of the Soviet Union. A number of variations of the flag design have been used, but all of them contain two elements: the Russian text Vperëd Rossiia, which means “Forward Russia”, and a bear which appears to be breaking its way out of the flag.

To Westerners it seems only logical that the bear would be the animal selected to represent Russia on a flag celebrating Russian sporting might. However, to those familiar with the symbolism used by Russians to represent their own country, it illustrates an interesting trend in post-Soviet Russia. This paper examines various aspects of the “Russian bear” including the portrayal of bears in Russian folklore, bears used in Russian heraldry, Western usage of the bear to represent Russia, and the adoption of the bear by Russians as a symbol of national pride.

The Bear in Russian Language and Folklore

An examination of the bear within the context of Russian culture provides contrasting examples of how Russians have viewed this animal. First, linguists have long been fascinated by the very word used in Russian for the bear. Unlike many language groups within the Indo-European family of languages, the Slavic languages generally do not use words based upon the old Indo-European word for “bear”. Instead, most Slavic languages use what linguists call “substitutes”. For example, in the Russian language the word for “bear”— medved’ actually means “honey-eater”, and the roots of the word combine for an additional meaning of “knowledge of honey”. Russians commonly refer to bears by secondary substitution terms, as well, such as the names “Misha” or “Mishka”, diminutives of the male name “Mikhail” (Michael). This is similar to English-speakers sometimes calling bears “Teddy”, although the origin of the usage came about differently in the two languages. In addition, other secondary substitutions have been employed to avoid using even the substitution term that the language assigns to the animal. Such terms mean “black beast”, “beast with large paws”, “clumsy one”, “shaggy”, “forest devil”, “black disease”, and “ant-eater”.[1]

While linguists agree that these substitution terms are an interesting aspect of the language, they do not agree on the reason the substitutions occurred in the first place. Two theories offer plausible explanations for how the avoidance of a direct term for “bear” evolved in Russian—a “hunter’s taboo” and a “religious taboo”. One explanation of the “hunter’s taboo” is a belief that if hunters spoke the name of the bear aloud, rather than referring to it by a euphemism, the animal might overhear and evade the hunters. Another explanation offered by proponents of this theory is based upon the belief in many early cultures that the spoken word had magical evocative power. For example, if the actual name for “bear” rather than the substitute term were spoken aloud, it could result in the surprise manifestation of the animal before the hunter. In contrast, the “religious taboo” theory explains the practice of using substitute terms within a religious context. In this theory, the bear is connected with the supernatural world and therefore the avoidance of using its true name could either be attributed to fear or reverence. Regardless of which theory is correct, it is clear that within the context of the Russian language the bear holds a special position.[2]

Some have suggested that the bear’s linguistic status is connected to the bear cults that were found across many parts of pre-Christian Russia. Others note that much respect was given to this animal because of its connection with the cycle of the seasons. To the ancient Slavs the animal’s ability to hide underground during the winter only to come back to life in the spring made it a subject of both respect and celebration. In fact, in some Slavic communities the emergence of the bear from hibernation was celebrated on 23 March with a holiday called Komoeditsa. This traditional observance of the spring equinox has for the most part been absorbed into the Maslenitsa (“Butter Week” or “Pancake Week”) celebration which occurs during the seventh week before Easter.[3]

Assessment of the role of the bear in Russian folklore offers scant clarification of the relationship between the Russians and the bear. In traditional folktales, the bear plays a variety of roles, not all of which are particularly flattering. Some tales do ascribe supernatural status to the bear. In his books describing Russian folktales, Jack V. Haley describes one tale that explains the origin of bears. In the story, an old man goes into the forest to cut some firewood. A magical linden tree agrees to provide the man and his wife with certain quantities of wood in exchange for the man’s promise not to cut down the tree. Over time, the man’s greedy wife sends him back to the tree several times to extort first grain, and then money, from the tree. Finally, worried that their wealth will attract robbers, the man asks the tree for something to protect their home against thieves. The tree agrees and when the man returns home he trips over the threshold and is transformed into a bear. When his wife tries to escape, she also trips and becomes a bear. According to Haley, this story reflects a widespread folk belief among early Eastern Slavs that the bear was their common ancestor. Other stories in which bears have supernatural relationships with humans include either a man or a woman who has become the consort of a bear, or feature the offspring produced by a human-bear coupling.[4]

More often, however, the bear is portrayed in less-than-admirable ways in Russian folktales. The animal is often characterized as good-natured, overly trusting, gullible, stupid, lazy, clumsy, and a bit careless with its own strength. Frequently, the bear is exploited or tricked by other animals. In one story, a fox swindles his bear friend out of all his butter. In another, a bear tries to convince the other animals that they should build a warm hut for the winter. While none of the other animals are willing to assist in the construction of the hut, one by one they coerce the bear into letting them into the hut where it is warm. Very rarely does the bear get the better end of encounters, no matter if they are with other wildlife, domesticated animals, or humans. Usually, the bear suffers indignity, exploitation, or even death at the hands of the other characters in the stories.[5]

Bears in Russian Heraldry

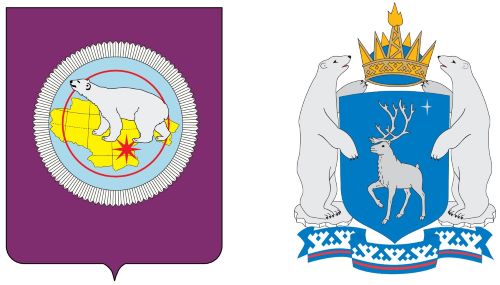

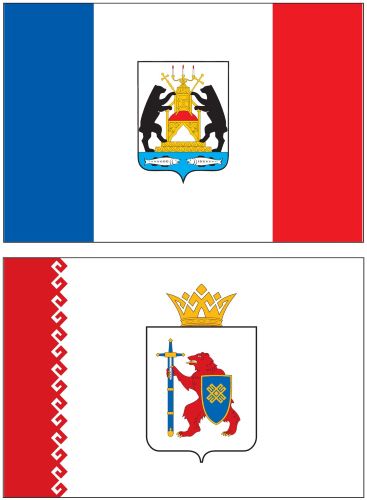

The regional heraldry of the Russian Federation has, in most cases, continued the heraldic tradition of pre-Soviet Russia. However, among the symbols used in arms and flags there are relatively few bears. The arms of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, one of Russia’s most northern territories, features a polar bear. Two polar bears also act as supporters on the arms of Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. There are bears, in these cases black bears, on the arms of the Republic of Karelia and Khabarovsk Krai.

Two black bears act as supports for the throne in the arms of Novgorod Oblast and are repeated in the simplified arms on the oblast’s flag. Both the arms and flag of the Republic of Marii El feature a bear. In all of these cases, the bears represent the region’s indigenous wildlife, rather than the “Russianness” of the people or region.[6]

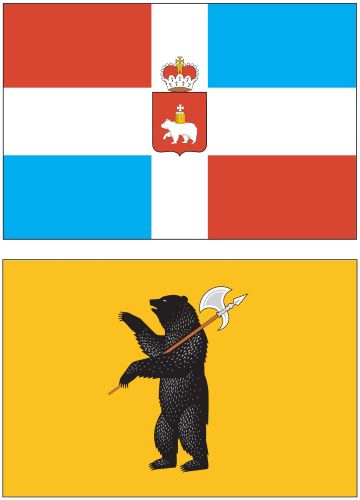

On the arms of Perm Krai, as well as on the arms shown on the flag, there is a more unusual bear. This bear carries the Book of the Gospels on its back, symbolizing how Christianity replaced the bear cult that had once been found in the territory.

A similar story is represented on the arms and flag of Yaroslavl Oblast. On those symbols, the bear symbolizes how Yaroslav the Wise slew a local cult’s sacred bear in order to convert the people to Christianity. So, in these cases the bears represent how the new religion (Russian Orthodox Christianity) defeated and replaced the earlier religion of the area. While there are bears used in regional heraldry, the animal has not been used in the heraldic symbols or the formal symbolism of the Russian Federation at the national level.[7]

So, when one looks at the linguistic background of the word for “bear” in Russian, examines the role of bears in Russian folktales, and considers the use of bears in Russian heraldry, the question arises—“just how did the bear become known as a symbol of Russia?” The answer lies far west of the Russian border.

Portrayal of the Russian Bear in Western Sources

It is difficult to trace the first usage of the bear as a symbol of Russia in the West. The earliest references used bears as illustrations of the fauna of the country. As one Russian scholar put it, “bears were only an exotic attribute of a mysterious country”. Examples can be found as far back as the 17th century in the literature of Europe. Even Shakespeare worked the untamed image of the Russian bear into his work, as illustrated by Act 3, Scene 4 of Macbeth. In the scene, Macbeth confronts the ghost of Banquo declaring that he was brave enough to face the spirit no matter how frightening the form he might take:

What man dare, I dare:

Approach thou like the rugged Russian bear,

The arm’d rhinoceros, or the Hyrcan tiger;

Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble: or be alive again…

Of course, Macbeth’s application of the adjective “Russian” to his bear reference is not being used to symbolize the country of Russia. Rather, it illustrates how little Europeans knew about Russia. The “Russianness” of the bear seems to imply that it would be somehow more exotic, wild, and dangerous than some other bear. For most Europeans at this time, Russia was a land of unknowns—wild, untamed, and full of dangers.

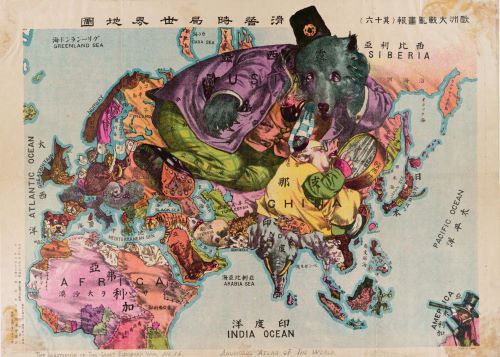

This perception was also evident in maps produced during this era. Mapmakers throughout the centuries have used exotic animals as embellishments to illustrate the fauna typical of different regions. They also used such illustrations to mark wild, unknown areas of the world. On maps it became popular to use bears within this context to mark the wild unknown regions of Russia. An early example is a map of Europe published in 1660 by Willem Janszoon Blaeu (Guilielmo Blaeuw), a Dutch cartographer. On the map several small bears inhabit the wilds of Russia, while a pride of lions marks the northern part of Africa. In both cases the implications are that those regions of the map are still the realms of wild animals.[8]

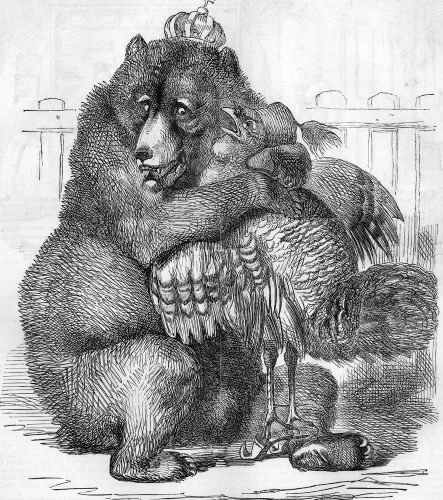

In later decades, the bear image evolved into an actual symbol of the country and its people. One of the earliest “bear” images in this category was a caricature entitled “The Russian Bear and Her Invincible Rider Encountering the British Legion”, published in April 1791. The image shows a bear with the head of Empress Catherine II (the Great). She is serving as a mount for Russia’s General Potemkin. England’s King George III and his ministers confront the duo. In later caricatures it was not uncommon to portray Russian leaders as human-bear hybrids or as bears dressed in human clothing and standing erect.[9]

Another early instance was a cartoon commonly referred to as “The Bear, the Bulldog, and the Monkey” published in August 1812 as French troops were marching toward Moscow. In the image, Napoleon is portrayed as a monkey in the clutches of a bear and a bulldog. The bear represents Russia, while the bulldog (labeled “Wellington” on its collar) represents Britain. Regardless of when and where the first usage of the bear symbol occurred, it was popularized in the media of Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. Political caricatures and cartoons using bears to represent Russia appeared frequently in the popular periodicals of the 19th century such as Britain’s Punch, or the London Charivari (usually just referred to as “Punch”), and America’s Harper’s Weekly.[10]

A survey of bear cartoons published in the Punch and Harper’s Weekly offers a variety of Western attitudes about Russia and events that brought the Russian Empire to attention of the Western media. The cartoons frequently portrayed the competition between Russia and Western powers to assert influence over central and eastern Asia. For example, in early 1853 tensions increased between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Western governments became concerned as Russia moved troops into the Danube region, presenting a direct threat to Turkey. “Turkey in Danger” appeared in Punch in the months before the outbreak of the Crimean War, illustrating perceived Russian intentions towards the region. By October of that year, the Turks had formally declared war on Russia, and eventually Britain, France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Duchy of Nassau joined the war on the side of the Ottoman Empire. The Crimean War of 1853–56 was fought not only on the battlefield, but also on the home front through political cartoons. For the caricaturists of the West, the Russian bear was a favorite symbol for the Russian Empire during the conflict. Nearly two decades later, Russia and Turkey were still competing for influence in the region.

Another Russia-Turkey cartoon, which appeared 22 October 1870, implies that even after the war the Russian bear still had intentions toward Turkey. “Russia and Turkey; Or, Which is the Gobbler?” appeared in Harper’s Weekly with a poem, illustrating that little had been resolved.[11]

Other cartoons from the decades of the 19th and early 20th century continued to use the bear symbol as Russia expanded its influence throughout Asia. In “Save Me From My Friends”, published in Punch in November 1878, the Ameer of Afghanistan watches warily as both the Russian bear and the British lion contemplate their next move. And, as Russia and Japan squared off in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), the cartoonists were quick to document it. So, while the bear in the cartoons was not always shown as an aggressor, it certainly conveyed the message that Russia was a big country that should be watched carefully.[12]

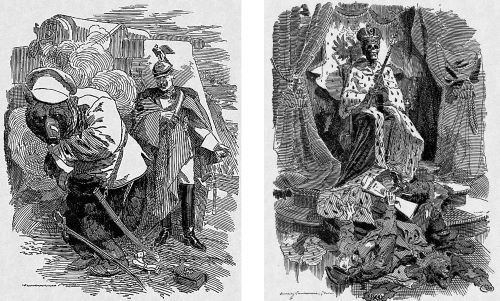

Not all the cartoons were about Russian expansionism, however. Events within the established Russian Empire did not escape the notice of the cartoonists. An example would be the events related to the “January Uprising” which began in 1863. While it was initially sparked by young Poles protesting against conscription into the Russian army, the conflict spread through the territories of present-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, Ukraine, and parts of Western Russia. The Russians did not completely reassert full control over the region until 1865. Two cartoons from Punch demonstrate Western Europe’s fascination with Russia’s imperial difficulties. In the first, entitled “A Growl for Poland”, a young woman representing Poland bravely swings her chains and stands her ground against a well-armed Russian bear. John Bull, a symbol of England, stands to one side watching and illustrates Britain’s official position of neutrality during the conflict. In “The Amnesty”, Poland seems to be getting the upper hand as she pummels the bear with the butt of a rifle. Figures representing France, Austria, and Britain watch from a distance.[13]

Other cartoons documented the internal problems within Russia. As revolutionaries stirred up unrest at home, it was clear from the images that the bear was not always as strong as it looked. A cartoon from an issue of Harper’s Weekly published in May 1879 is an example. In “More Trouble Bruin—Something the Matter Inside Now” Russia is portrayed as an injured bear, fatigued by war with Turkey and suffering from an internal illness. Another ailing bear appeared in both Punch and Harper’s Weekly in September 1904 while Russia was engaged in the Russo-Japanese War.

In the cartoon, entitled “Internal Disorder”, the bear says “It’s not only the fighting—it’s the awful pain inside”. As the cartoon suggests, military defeats combined with widespread discontent in the country had severely weakened the reign of Tsar Nicholas II. Another cartoon, published in March 1905, illustrated the tenuous position of the monarchy as Russia was racked by revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905 resulted in many concessions on the part of the Tsar. As Russia appeared to be self-destructing, Nicholas was pictured as a skeleton reigning over a dead peasant and a bearskin rug. The caption read “The Czar of All the Russias”. On 5 September 1905, Russia signed the Treaty of Portsmouth and agreed to give up its ambitions in East Asia. Twelve years later Nicholas II was forced to abdicate the throne after the February Revolution of 1917, and then the October Revolution of 1917 swept the Bolsheviks into power.[14]

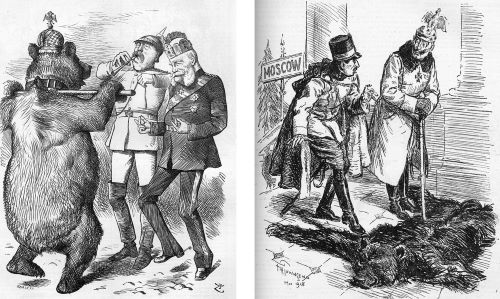

Even when Russia was attempting to secure peace through diplomatic means, the bear was subjected to various forms of humiliation. For example, a Punch cartoon entitled “O, Lovely Peace”, published in May 1875, shows Prussian statesman Prince Otto von Bismarck-Schonhausen leading a tamed Russian bear by a collar. Bismarck plays a tune on a penny whistle while Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary dances along. Another Punch cartoon published after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 reflects the British view of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The new government had signed the treaty in March 1918 giving up Russian claims in the Baltic region in order to extract Russia from World War I. In “A Walk-Over?”, Germany’s Emperor Wilhelm II treats the Russian bear as a doormat, while Austrian emperor Charles I cautiously follows him.[15]

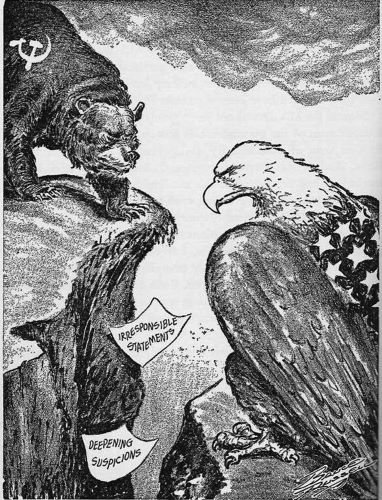

Following the Russian Revolution, the image of the bear came to represent the entire Soviet Union. Cartoons from World War II showed the bear in more favorable light as it fought off the Nazi aggressors. But that goodwill was short-lived, for as the war came to an end it became apparent that the new world order divided Europe into two opposing camps—the allies of the United States in the West, and the allies of the Soviet Union in the East. This new division was illustrated in a cartoon published in November 1945, as the Cold War era began. The bear wears the hammer and sickle symbol of the communist Soviet Union. It stares across the chasm at the American eagle, the two of them separated by “irresponsible statements” and “deepening suspicions”—represented by the papers falling into the gap. The Soviet bear did not have just the West to worry about.

In a cartoon published in 1978, the bear finds itself facing off against the Chinese dragon. During that period, these two communist nations—the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China—found themselves in conflict over old border disputes which predated the revolutions in the two countries. For Westerners, the cartoon was probably reassuring, since while the bear was engaged in Asia it would be less of a threat to the nations of Western Europe.[16]

One of the most interesting uses of the bear in Western media during the Cold War occurred during the 1984 presidential election in the United States. At that time, President Ronald Reagan was running for re-election. A popular president, he frequently used Cold War rhetoric to portray himself as a strong leader for America. Perhaps the most memorable television advertisement of his campaign was the “Bear in the Woods” ad. The 30-second spot featured imagery of a bear walking through the woods, with a drumming heartbeat soundtrack in the background. As the bear moved through the forest, the narrator spoke:

There is a bear in the woods. For some people, the bear is easy to see. Others don’t see it at all. Some people say the bear is tame. Others say it’s vicious and dangerous. Since no one can really be sure who’s right, isn’t it smart to be as strong as the bear? [Pause.] If there is a bear.

At the end of the ad, the bear encountered a man with a gun up on a ridge. The bear paused, and then took a step backward. At this point, the bear was replaced by a photo of President Reagan with an American flag, underneath text reading “President Reagan: Prepared for Peace.” For those familiar with the meaning of the bear symbol, the ad reminded them of Reagan’s Cold War belief that the armed might of the Soviet Union was a direct threat to the United States. It suggested to voters that politicians who refused to acknowledge the threat would leave America unprepared to face Soviet aggression. It also reinforced Reagan’s message of protecting America through the pursuit of an arms race with the Soviets. And, even for those who missed the allusion to the Soviet Union implied by the bear, the message was still clear—President Reagan would make American strong. In retrospect, the ad is a clear testament of the power of the bear as a symbol of Russia and the Soviet Union. There was no mention of the Soviets in the ad, but the threat they represented in Reagan’s world view was clearly represented by the footage of the bear.[17]

Even after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the bear symbol remained popular in the West. Searching through lists of articles relevant to post-Soviet Russia, the word “bear” is frequently found in the titles. And, when Russian troops invaded the nation of Georgia in 2008, images of the aggressive Russian bear were once again common in Western political cartoons. The bear image, as used in Western media, certainly carries with it many assumptions about the characteristics of Russia, the Russian government, and sometimes even the Russian people.

Characteristics of the Russian Bear

A 2009 survey conducted in both the United States and the Russian Federation polled 100 people in each country. Those polled were asked which of the listed symbols, according to their opinion, represented Russia. The most popular choice of symbol among the Americans was the bear (selected by 46% of those surveyed). This choice was followed by Red Square (39%); Mother Russia (32%); the Kremlin, “Matroshka” nesting dolls, and the AK-47 (each with 29%); followed by the two-headed eagle, the birch tree, and the Volga River (each with 7%); and Vladimir Putin (4%). However, among Russian respondents, the two-headed eagle was the most popular symbol, selected by 56% of those polled. Other choices also placed above the bear for the Russians, namely the Kremlin (38%) and the birch tree (23%). Only one-fifth (20%) of those surveyed in Russia selected the bear as one of their symbols for Russia. This was followed by “Matroshkas” (17%), the Volga (14%), Mother Russia (10%), the AK-47 (7%), and Putin (6%).[18]

Next, the respondents were asked about the portrayal of Russia as a bear in Western mass media and given a list of both positive and negative attributes. They were then asked to pick the top ten characteristics attributed to Russia through the use the symbol. Americans chose the following terms: aggressiveness (77%), strength (63%), brutality/cruelty (54%), barbarity (23%), good nature (13%), wisdom (13%), calmness (4%), artlessness/ingenuousness (4%), and stupidity (2%). The Russian respondents chose strength (58%), backwardness (43%), awkwardness/clumsiness (37%), aggressiveness (25%), stupidity (21%), good nature (14%), imperialism (6%), barbarity (5%), and artlessness/ ingenuousness (5%). Within each group of respondents about 13% of both Americans and Russians substituted their own terms as their 10th choice.[19]

T hese responses clearly reflect that both the Americans and Russians surveyed understood how the bear symbol had been used in the West to symbolize Russia. Throughout centuries of use, the bear image has illustrated the sheer size of Russia, its strength, its industrial development relative to that of Western countries, and its ability to defend itself when provoked. It has also been used to suggest that Russia can be aggressive and dangerous to those who oppose its interests. The poll results also tell us something interesting about the bear symbol. While it was not the most popular symbol of Russia selected by the Russians questioned, 20% did accept the bear as a symbol to represent their country. What had once been a symbol of the Western stereotype of Russia now seems to be a symbol recognized by the people of the Russian Federation themselves.

Adoption of the Bear as a Russian Symbol of Russia

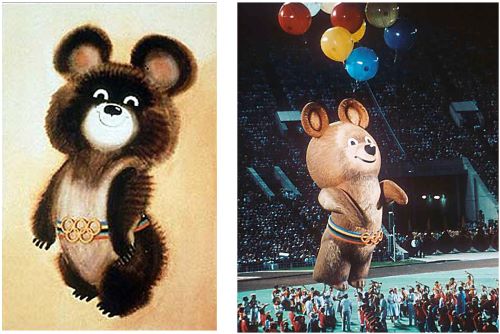

During the Soviet era, a bear was selected to be the mascot for the 1980 Summer Olympic Games. The games were held in Moscow and marked the first time that Russia or the Soviet Union had hosted the world’s most notable sporting event. While “Misha” was not specifically a symbol chosen to represent “Russia”, it is very likely that a bear was selected because of its association with Russia in other countries. Also known as “Mishka” or “The Olympic Misha”, the mascot was designed by Victor Chizhikov, a Russian illustrator known for his work on children’s books. Misha had all the characteristics which the Soviet hosts wanted to portray to the world—he was large, furry, smiling, affable, and lovable. He clearly portrayed the friendly image that the Soviets wished the world to see when they visited Moscow for the games. In the spirit of internationalism, he wore a striped belt of the Olympic colors with a buckle of Olympic rings.[20]

Misha the Olympic bear appeared on a variety of merchandise related to the Moscow games, as well as in an animated television series. Unfortunately for the organizers, most Western countries boycotted the Moscow Olympics in protest after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on 27 December 1979. Thus, the Olympic Misha missed his opportunity to serve as a positive bear symbol of Russia and the Soviet Union, and instead enjoyed popularity mostly within the Soviet Union.[21]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 the bear began to be used as a symbol of “Russianness” within the Russian Federation. One clear illustration is on the logo of its largest political party, Edinaya Rossiya (United Russia or One Russia), founded in 2001. The best-known leader of the party is Vladimir Putin, who has served as both prime minister and president of the country. Party member Dmitrii Medvedev was elected as Russia’s third president when Putin was precluded from running again due to term limits, and then succeeded by Putin in 2012. In addition, Edinaya Rossiya currently holds a majority of seats in the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian legislature. The party describes itself as conservative and “right of center”. It has gained popularity due to its efforts to restore political and economic stability to Russia, to return Russian to a position of strength in the international arena, and to assert Russian power when it has been perceived necessary to protect Russian interests.[22]

The party has used several different bear logos since its formation. In an early version, adopted in 2003, the Russian tricolor was used as the background of a circle with a geographic image of the Russian Federation at the top, the party name in Russian in the middle, and a brown bear walking along the bottom. The party changed its logo in 2005 so that it now shows a stylized Russian flag flying over the bear, with the party name below. The biggest change is in the color of the bear, which is now shown in white.[23]

The “Forward Russia” Flag

And now we return to the “Forward Russia” flag. This flag is not a onetime emblem for a specific sporting event, nor is it a political symbol. Rather, it has become a symbol of Russian pride and support for national sports teams. The flag first appeared 17 October 2007 during the qualification matches for the 2008 UEFA European Football Championship. Before a game in Moscow between England and Russia, fans displayed a huge flag at one end of the stadium. The flag was 80 meters by 130 meters, and was believed to be a world record. Playing on the Western stereotype of the aggressive Russian bear, the banner showed a fierce bear bursting through the tricolor field of the flag of the Russian Federation. On the flag were the words “Vperëd Rossiia”. This phrase is usually translated as “Forward Russia”, but could also be interpreted as “Advance Russia” or “Go Russia”. In the match the Russian team defeated England 2–1. Fans, ecstatic about the Russian victory over a long-time soccer power, joked that the English team had been intimidated by the bear. Others wanted to buy their own smaller copy of the flag. Several manufacturers within the Russian Federation now offer variations of this flag for sale. While the details of the bear’s design and placement of the words vary from maker to maker, all the designs carry the same basic elements.[24]

The flag is now well-known among fans of the Russian national teams, primarily those of the hockey and soccer teams. Russian fans waved it enthusiastically during the 2010 Winter Olympic Games in Vancouver, Canada, and the flag will surely make appearances at future Olympics, especially the Winter Games to be held in Sochi, Russia in 2014. Russians consider the flag a “sporting flag” and it is used only within the context of international sporting events.

The symbolism of the flag is, for the most part, obvious. The field of the flag incorporates the traditional Russian tricolor, which dates back to tsarist times. Readopted in 1991 as the flag of the Russian Federation after the breakup of the Soviet Union, it has become a symbol not just of the nation but also of “Russianness”. The bear, as discussed, is a well-established symbol of Russia both abroad and now within Russia. This particular bear personifies the strength and aggressiveness of the Russian national team, perhaps in an attempt to link the teams of the modern Russian Federation back to the sporting success enjoyed by the national teams of the Soviet Union. The phrase “Vperëd Rossiia”, meaning “Forward Russia”, has been used in several different contexts within Russia. For example, in the 1990s a voting bloc in the Russian State Duma used the name “Vperëd, Rossiia”. While the coalition no longer exists, the phrase is now popular in Russia. In 2009, President Dmitrii Medvedev wrote an article entitled “Rossiia, vperëd”. In Russian, the inversion of word order placed emphasis on the direction in which he wanted Russia to go: “Russia—Forward”. So, while the phrase has been used in a political context, its meaning has now moved beyond politics and into the realm of national pride.[25]

Conclusion

While not as well known as other sporting flags such as Australia’s “Boxing Kangaroo” and New Zealand’s “Fighting Kiwi”, the “Forward Russia” flag will likely gain more popularity as Russians endeavor to reestablish a record of sporting success for their national teams. As more Russian fans obtain their own copies of the flag and attend events, it will probably gain more recognition on the international scene. Unlike most other sporting flags, it incorporates the field of the national flag, clearly identifying its association with the Russian Federation. The motto on the flag draws on national politics and the desire of Russians to reestablish Russia’s place as a major world power, both politically and in the realm of international sports. Finally, the flag firmly establishes the bear as a symbol of a proud Russia. The Russians have now claimed this inconsistent symbol as their own. No longer is the bear a symbol of the Western stereotype of Russia. The Russians have now claimed this inconsistent symbol as their own.

Endnotes

- Maria Zagórska Brooks, “The Bear in Slavic and Polish Mythology and Folklore”, in: For Wiktor Weintraub: Essays in Polish Literature, Language, and History Presented on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday (The Hague: Mouton, 1975): pp. 107–111; M. B. Emeneau, “Taboos on Animal Names”, Language v. 24 #1 (Jan.–Mar. 1948): pp. 56–63; Eugenio Ramón Luján Martínez, “Pragmatics and Indo-European Linguistics”, Journal of Pragmatics v. 28 #2 (Aug. 1997): pp. 189–204; R. Smał-Stocki, “The Displacement of the Indo-European Words for Bear in Slavic—a ‘Religious Taboo’ Phenomenon?”, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages Bulletin v. 6 (1949): p. 80; Wilfred P. Lehmann, Historical Linguistics: an Introduction, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 90, 260–264; “Medved’: Etimologiia”, Vikislovar’, http://ru.wiktionary.org, accessed 4 September 2010; “Medved’”, Zhivoe slovo: Zabytiia etimologiia drevnego iazyka, http://korneslov.ru/publ/16-1-0-96, accessed 4 September 2010; “Medved’”, in A. G. Preobrazhensky, Etymological Dictionary of the Russian Language (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), p. 519; “Ved-”, in Catherine A. Wolkonsky and Marianna A. Poltoratzky, Handbook of Russian Roots (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), p. 27.

- Zagórska Brooks and Emeneau.

- “Komoeditsa (prazdnik)”, Vikipediia: svobodnaia entsiklopediia, no direct URL available, accessed 15 August 2010; “Maslenitsa”, Wikipedia: the Free Enclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslenitsa, accessed 15 August 2010; Jack V. Haney, An Introduction to the Russian Folktale, v. 1 of The Complete Russian Folktale (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1999), pp. 65–69.

- Haney, An Introduction to the Russian Folktale, pp. 69–70.

- Jack V. Haney, Russian Animal Tales, v. 2 of The Complete Russian Folktale (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1999), pp. xxxvi–xxxvii, 10–13, 28–31, 36–37, 68–69, 84, 99–101, 107–109, 115–130, 136–139, and 158–159; Alex E. Alexander, Russian Folklore: An Anthology in English Translation (Belmont, Massachusetts: Nordland Publishing Co., 1975), pp. 206–210.

- Anne M. Platoff, Russian Regional Flags: The Flags of the Subjects of the Russian Federation, published as volume 16 of Raven: A Journal of Vexillology (Trenton, New Jersey: North American Vexillological Association, 2009), pp. 49, 63, 65, 89, and 134; “U respubliki poiavilsia novyi gerb i flag”, Respublika Marii El: ofitsial’nyi internet portal, (9 March 2011) http://portal.mari.ru/president/Pages/News/2011/110309_1.aspx, accessed 2 May 2012. Images of flags and arms purchased from Vector-Images.com.

- Platoff, pp. 95–96 and 127. Images of flags and arms purchased from VectorImages.com.

- Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Europa recens descripta à Guilielmo Blaeuw, map (1660); at http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/?/en/items/NESA01:L01-0100, accessed 1 September 2010; A. Rossomakhin and D. Khrustalëv, “Rossiia kak medved’: Istoki vizualizatsii (XVI–XVIII veka)”, conference paper, Russkii medved’: istoriia, semiotika, politika (Ivanovo-Ples: Sentr etnicheskikh i national’nykh issledovanii Ivanovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 21–22 May 2009) http://cens.ivanovo.ac.ru/almanach/rossomahin-khrustalev-2008.htm (accessed 25 June 2010); Andrei Rossomakhin and Dennis Khrustalev, “Rossiia kak medved’” Neprikosnovennyi zapas no. 1 (57) (2008), http://magazines.russ.ru/nz/2008/1/ro14.html, accessed 25 June 2010; Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders, The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature (New York: Viking, 1985), pp. 34, 155.

- “The Russian Bear and Her Invincible Rider Encountering the British Legion”, political cartoon (19 April 1791), Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99404723, accessed 23 August 2010.

- “The Bear, the Bulldog, and the Monkey”, political cartoon, in A. M. Broadley, Napoleon in Caricature: 1795–1821 (New York: John Lane Company, 1911), pp. 310–313; Donald Dewey, “Drawing Russia”, Russian Life, v. 49 #5 (September/October 2006), pp. 44–49; “Russian Bear”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_Bear, accessed 22 August 2010; “Russkii medved’”, Vikipediia: Svobodnaia entsiklopediia, no direct URL available, accessed 22 February 2010; Oleg Riabov and Andrzej de Lazari, “Misha and the Bear: The Bear Metaphor for Russia in Representations of the ‘Five-Day War’”, Russian Politics and Law, v. 47 #5 (September–October 2009), pp. 2639; Robert Philippe, Political Graphics: Art as a Weapon (New York: Abbeville Press, 1980), pp. 164, 166–169, 184–186.

- “Turkey in Danger”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 24 (9 April 1853), p. 145; “Russia and Turkey; Or Which is the Gobbler?”, political cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, v. 14 #721 (22 October 1870), p. 683 [scanned image from the HarpWeek database]; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39; Anthony Cross, “The Crimean War and the Caricature War”, The Slavonic and East European Review, v. 84 #3 (July 2006), pp. 460–480; Dewey, pp. 44–49; Philippe, pp. 164, 166–169, 184–186.

- “Save Me From My Friends”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 75 (30 March 1878), p. 247; “All the World Waits”, political cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, v. 48 #2455 (9 January 1904), p. 70 [scanned image from HarpWeek]; Brandeis University, Archives & Special Collections Dept., The Crimean War in the French and British Satirical Press, online exhibit (August 2006), http://lts.brandeis.edu/research/archives-speccoll/exhibits/crimeanwar/TurkeyBear.html, accessed 18 August 2010; Philippe, pp. 164, 166–169, 184–186; Dewey, pp. 44–49; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- “A Growl for Poland”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 44 (21 February 1863), p. 75; “The Amnesty”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 44 (25 April 1863), p. 171; “January Uprising”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/January_uprising, accessed 29 August 2010.

- “More Trouble Bruin—Something the Matter Inside Now”, political cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, v. 23 #1168 (17 May 1879), p. 391; “Internal Disorder”, political cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, v. 48 #2492 (24 September 1904), p. 1478; “The Czar of All the Russias”, political cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, v. 49 #2516 (11 March 1905), p. 374 [scanned images from HarpWeek].

- “O, Lovely Peace”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 68 (22 May 1875), p. 219; “A Walk-Over?”, political cartoon, Punch, or the London Charivari, v. 154 (27 March 1918), p. 195.

- “Time to Bridge That Gulch”, political cartoon, Los Angeles Times (30 November 1945), p. A4; “Pulitzer Prize Awarded to ‘Times’ Cartoonist: Bruce Russell Honored by Committee for His Work Depicting Rift Between U.S. and Russia”, Los Angeles Times (7 May 1946), p. 1; [Chinese Dragon Breathing Fire on the Soviet Bear] (24 August 1978), In Edmund Valtman: The Cartoonist Who Came in From the Cold, online exhibit (14 March 2003), Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/valtman/presentation.html, accessed 8 September 2010.

- “Bear in the Woods” political ad, obtained from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library; Ted Brader, Campaign for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006): pp. 6–10; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39; Megan Cruise, “Reagan’s ‘Bear’ Parable”, http://search.colorado.edu/pwr/occasions/articles/Cruise_Reagan’s%20Bear%20 Parable.pdf, accessed 27 June 2010; Edwin Diamond and Stephen Bates, The Spot: The Rise of Political Advertising on Television, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT, 1992): pp. 24–28; A. Trevor Thrall, “A Bear in the Woods?: Threat Framing and the Marketplace of Values”, Security Studies v. 16 #3 (JulySept. 2007), pp. 452–488.

- Tat’iana Riabova, Ekaterina Tsalko, and Leonid Godunov, “Medved’ kak simvol Rossii: Sotsiologicheskoe izmerenie”, unpublished conference paper, Russkii medved’: istoriia, semiotika, politika (Ivanovo-Ples: Sentr etnicheskikh i national’nykh issledovanii Ivanovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 21–22 May 2009), text provided by Godunov (1 April 2010); Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- Ibid; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- “Misha”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Misha, accessed 22 August 2010; “Russian Bear”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia; “Russkii medved’”, Vikipediia: Svobodnaia entsiklopediia.

- “1980 Summer Olympics”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Moscow_1980, accessed 22 August 2010; Misha images from web site “Letnie Olimpiiskie igry 1980”, http://www.savok.name/176-olimpiada-1980. html, accessed 6 September 2010; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- “United Russia”, Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edinaya_Rossiya, accessed 22 August 2010; “Simvoly politicheskikh partii Rossii”, Vexillographia, http://www.vexillographia.ru/russia/mod_par3.htm, accessed 22 August 2010; “Medved’ navsegda: ‘Edinaia Rossiia’ gotova obnovit’ simboly”, Rossiiskaia gazeta – Federal’nyi vypusk, no. 3935 (25 November 2005), http://www.rg.ru/2005/11/25/edinorossi.html, accessed 22 August 2010; “‘Edinaia Rossiia’ pomeniala simvoliku: buryi medved’ stal belym”, NEWSru.com, (26 November 2005), http://www.newsru.com/russia/26nov2005/medv.html, accessed 22 August 2010; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- “Simvoly politicheskikh partii Rossii”, Vexillographia; Riabov and de Lazari, pp. 26–39.

- Victor Lomantsov, personal communication, 27 June 2010; “Futbol’nyi match Rossiia – Angliia” (2007), Vikipediia: Svobodnaia entsiklopediia, no direct URL available, accessed 5 September 2010; “Dlia sportivnykh bolel’shchikov”, BIAR Natsional’naia Simvolika, http://www.biar.ru/support.php?id=5, accessed 5 September 2010; “Flagi dlia bolel’shchikov”, BIAR Natsional’naia Simvolika, http://www.biar.ru/news.php?id=123, accessed 5 September 2010; “V Edinoi Rossii otkrestilos’ ot burgoo medvedia pobedy”, Lenta-ru (18 October 2007), http://lenta.ru/news/2007/10/18/bear/, accessed 27 June 2010; stadium photo from Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:RussianBear.jpg, accessed 2 May 2011.

- Victor Lomantsov, personal communication, 27 June 2010; “Vperëd, Rossiia”, Vikipediia: Svobodnaia entsiklopediia, no direct URL available, accessed 5 September 2010; “Rossiia, vperëd,” Vikipediia: Svobodnaia entsiklopediia, no direct URL available, accessed 5 September 2010; “Rossiia, vperëd! Stat’ia Dmitriia Medvedeva”, web site of the President of Russia (10 September 2009), http://kremlin.ru/news/5413, accessed 5 September 2010.

Originally published by Raven: A Journal of Vexillology 19 (2012, 99-126), republished by UC Santa Barbara under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.