The Slave Narrative Collection provides a unique and virtually unsurpassed collective portrait of an historical population.

By Dr. Norman R. Yetman

Professor Emeritus of Sociology

The University of Kansas

Introduction

The Slave Narrative Collection, a group of autobiographical accounts of former slaves, today stands as one of the most enduring and noteworthy achievements of the WPA, Compiled in seventeen states during the years 1936-38, the collection consists of more than two thousand interviews with former slaves, most of them first-person accounts of slave life and the respondents’ own reactions to bondage. This introductory essay, which accompanied the Library’s initial 2001 release of the collection, was written by Norman R. Yetman, then Chancellors Club Teaching Professor of American Studies and Sociology and Chair of the American Studies Program at the University of Kansas, where he was also Courtesy Professor of African and African-American Studies and co-editor (with David Katzman) of the transdisciplinary journal American Studies. Among other publications, Yetman is the author of Life Under the ‘Peculiar Institution’: Selections from the Slave Narrative Collection (1970), also published under the title Voices from Slavery: 100 Authentic Slave Narratives (revised edition, 2000).

In 1855, John Little, a fugitive slave who had escaped to Canada, uttered this perceptive commentary upon attempts to convey the realities of the existence that he had fled: “Tisn’t he who has stood and looked on, that can tell you what slavery is–’tis he who has endured.” The view that slavery could best be described by those who had themselves experienced it personally has found expression in several thousand commentaries, autobiographies, narratives, and interviews with those who “endured.” Although most of these accounts appeared before the Civil War, more than one-third are the result of the ambitious efforts of the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to interview surviving ex-slaves during the 1930s. The result of these efforts was the Slave Narrative Collection, a group of autobiographical accounts of former slaves that today stands as one of the most enduring and noteworthy achievements of the WPA. Compiled in seventeen states during the years 1936-38, the collection consists of more than two thousand interviews with former slaves, most of them first-person accounts of slave life and the respondents’ own reactions to bondage. The interviews afforded aged ex-slaves an unparalleled opportunity to give their personal accounts of life under the “peculiar institution,” to describe in their own words what it felt like to be a slave in the United States.1

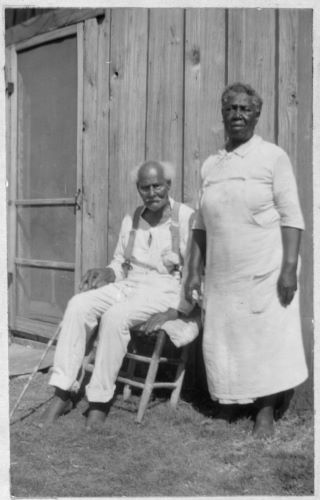

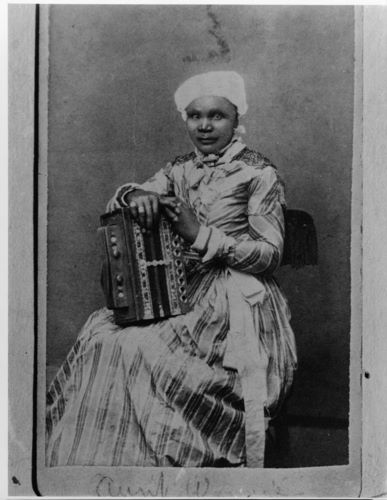

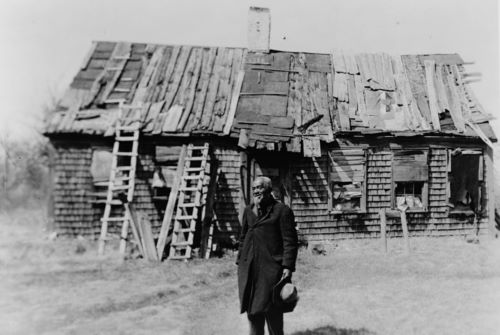

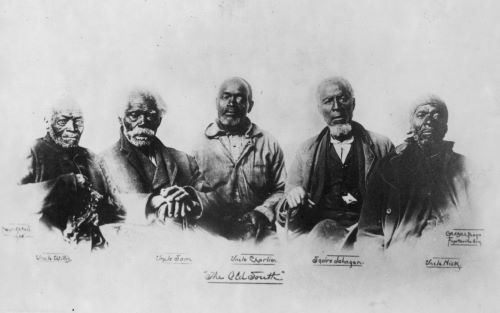

The Slave Narrative Collection provides a unique and virtually unsurpassed collective portrait of a historical population. Indeed, historian David Brion Davis has argued that the voluminous number of documented slave testimonies available in the United States “is indisputably unique among former slaveholding nations.”2 In addition to the substantial number of life histories it contains, the most compelling feature of the collection is the composition of the sample of people who made up its informants. Although not a representative sample of the slave population, they were a remarkably diverse and inclusive cross-section of former slaves. Those whose voices are included in the collection ranged in age from one to fifty at the time of emancipation in 1865, which meant that more than two-thirds were over eighty when they were interviewed. Almost all had experienced slavery within the states of the Confederacy and still lived there. They represented all the major slave occupations. Moreover, the size of the slave units on which respondents reported living varied considerably, from plantations with over a thousand slaves to situations in which the informant was his or her owner’s only slave. The treatment these individuals reported ran the gamut from the most harsh, impersonal, and exploitative to work and living conditions and environments that were intimate and benevolent. In fact, except that most of the informants were relatively young when they experienced slavery (older slaves had died long before these interviews were undertaken), all the major categories of the slave population appear to be well represented in the collection.

Because the actual occupational distribution of the slave population is unknown, assurance of total randomness in this sample is impossible. But there appears little reason to believe that the processes involved in the selection of interviewees produced a sample that systematically diverged from the larger population. At least the sample biases that characterized the universe of antebellum slave autobiographies–the disproportionate number of runaways, individuals who had purchased their freedom or had been freed, males, craftsmen, and individuals from border states–are absent. While not totally eliminated, the methodological problem of sample bias that inevitably confronts the historian is substantially reduced in this sample of the ex-slave universe. The WPA narratives thus constitute an illuminating and invaluable source of data about antebellum and post-Emancipation Southern life, the institution of slavery, and, most important, the reactions and perspectives of those who had been enslaved.

Slave Narratives from Slavery to the Great Depression

Slave Narratives During Slavery and After

The Slave Narrative Collection represents the culmination of a literary tradition that extends back to the eighteenth century, when the earliest American slave narratives began to appear. The greatest vogue of this genre occurred during the three decades of sectional controversy that preceded the Civil War. The avowed intention of the antebellum narrative was to challenge the roseate portrait of slavery painted by its apologists. The proslavery justification of the “peculiar institution” alleged that it was a benevolent system and that the position of the slave was more secure than that of the Northern wage earner. The slave, according to George Fitzhugh, one of the most vigorous of the proslavery propagandists, “was happy as a human can be.”3

But the stereotype of the “contented slave” was contradicted by the many fugitive slaves who sought refuge from bondage in the North and in Canada. Their often sensational revelations of the realities of slave life provided a persuasive challenge to Southern justifications of slavery. During the antebellum period thousands of autobiographical and biographical accounts of slave experiences were published and generally promoted and distributed by abolitionist propagandists. These narratives enjoyed immense popularity, were eagerly sought for publication by abolitionist journals, and proved financially successful. While it is difficult to weigh their precise influence on the antislavery crusade, there is little doubt that they effectively countered the propaganda of proslavery apologists.

The vogue for the slave narrative waned after the Civil War. The typical antebellum narrative had served as an exposé of the horrors of the “peculiar institution,” but the Civil War settled the issue of slavery and destroyed the narrative’s raison d’être. The sensational narrative of prewar vintage lingered on, but its publication after the war failed to elicit the same sympathy and enthusiasm. A nation weary of war and intent upon reconciliation expressed little desire to be reminded of the realities of life before the war. Most of the narratives that did appear in the half-century following Reconstruction–their number meager when compared to the plethora of antebellum narratives–reflected a radically different conception of slave life. Now the narratives were employed almost exclusively as a nostalgic and sentimental reaffirmation of the “plantation legend” popularized by Southern local colorists. While local-color treatment of the oral tradition of the ex-slave helped to sustain an interest in African-American folklore during the early years of the twentieth century, this alone proved insufficient to arouse a more general interest in recording ex-slaves’ accounts of life under slavery. As the ranks of former slaves dwindled, so did the possibility of preserving the “inside view” of slavery that their testimonies provided.

The Twentieth Century Revival

The late 1920s and 1930s witnessed a revival of interest in slave narratives. During this period several independent projects to secure ex-slave testimonies were undertaken. What most clearly distinguished these from earlier efforts was their sociological character. The single-minded moralism that had pervaded earlier narratives diminished substantially. The typical supplanted the dramatic as the primary focus of inquiry; detailed questionnaires were designed to obtain a catalogue of information on the daily round of slave life. The primary goal in each instance was simply to get aged African Americans to discuss the range of their experiences and impressions of life under the slave regime. The Federal Writers’ Project study that produced the Slave Narrative Collection was the most ambitious and comprehensive of several such efforts.

The reasons for the resurgence of interest in slave narratives are both numerous and complex. With the number of surviving ex-slaves rapidly diminishing by the 1930s, the time was imminent when their testimonies could no longer be obtained. This fact was often cited as a motivation by those compiling the narratives. However, while it goes far toward explaining the sense of urgency that inspired the several narrative-gathering efforts, it is insufficient to account for the heightened awareness of the narratives’ value at this particular time. The underlying sources of this interest must be sought elsewhere.

Slave Narratives and the New Debate about Slavery

Just as the antebellum slave narratives had gained prominence in reaction to the Southern defense of slavery, so interest in the latter-day slave narrative was stimulated by the dominant attitudes toward the slave regime that prevailed in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Seldom before or since has racism been so pervasive and so academically respectable in the United States. The assumption of the innate and inherited inferiority of non-Anglo-Saxon racial and ethnic groups permeated and dominated white intellectual and popular thought. Social, scientific, and historical thought both mirrored and reinforced this racism.

By far the most profound influence upon the historical study of slavery during this period was the writings of Ulrich B. Phillips, whose monumental American Negro Slavery established him as the leading authority on the subject.4 American Negro Slavery was so comprehensive, its scholarship so exacting, and its racial assumptions so closely attuned to those then prevailing, that it “succeeded in neutralizing almost every assumption of the anti-slavery tradition.”5 The portrait of slavery that emerged from this work bore a striking resemblance to that espoused by proslavery apologists before the Civil War. It minimized the severity of American slavery, extolled its civilizing and Christianizing functions, and reasserted the notion that the slave was submissive rather than defiant. The overall effect was a verification of the “plantation myth” and a confirmation of what Stanley M. Elkins has termed the “Sambo” image of the slave.

Against this background, the revival of interest in the slave narrative reflected a post-World War I revitalization of African-American culture that was instituted and promoted in large measure by blacks themselves. Most dramatically manifested in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, this revitalization was marked by a concerted quest for a “usable” past, one that would impart a sense of self-respect, dignity, and identity to African Americans. One result was the serious study of black history, spearheaded by the unremitting efforts and inspiration of W. E. B. DuBois and of Carter G. Woodson, the energetic founder, editor, and moving spirit behind the Journal of Negro History. The emergence of an increasing number of black scholars signaled the demise of black acquiescence to the prevailing white interpretations of the African-American past.

The authority of Phillips’s interpretation therefore did more than rekindle interest in the subject of slavery. Although accepted as authoritative in most academic circles, his sympathetic view was indignantly contested by the new generation of black scholars who, as the slaves’ blood and spiritual descendants, could not approach slavery in the spirit of erudition alone. Just as Phillips’s Southern background and heritage had exerted a profound and pervasive influence upon his view of slavery, so the portrait espoused by African Americans was derived from a tradition perpetuated and enriched by the accounts of those who had experienced life under the slave regime. When Phillips spurned the use of ex-slave reminiscences as historical data, he rejected the validity of the very source upon which many of the basic assumptions of African-American scholars were ultimately founded.

Phillips’s aversion to using slave narratives as appropriate sources of historical data also precluded the study of slavery written from the standpoint of the slave, since the sources he employed were inadequate to answer the question “What was it like to be a slave?” The recognition that only individuals who had lived under the slave regime could adequately answer this question contributed substantially to the surge of interest in obtaining the testimonies of former slaves.

Slave Narratives and the Waning Authority of Racism

The discovery of African-American culture during the 1920s and 1930s engaged the attention of a growing number of whites as well as blacks. White writers found in African-American life and culture a fresh source of artistic materials, and serious treatment of black culture was a distinguishing feature of the Southern literary renaissance that flourished in the 1920s. Interest in black art and entertainment was reflected in the acceptance of jazz by white musicians and its popularity among white audiences. Fascination with black folklore, which extended back to the nineteenth century, increased significantly during the twenties and was enlivened by innovations such as the unique brand of folk sociology pioneered by Howard W. Odum at the University of North Carolina.

This burgeoning interest in African-American culture was enhanced immeasurably by the rapidly expanding disciplines of anthropology and sociology. While social-scientific thought was not immune to the popular racial preconceptions of the day, the authority of such doctrines was weakened by the impact of intellectual currents from within the social sciences themselves. The concept of culture, more than any other single idea, contributed to the erosion of respectable racism. Although explicitly accepted only in avant-garde circles during the twenties, the culture concept had been an implicit and sometimes contradictory component of the working assumptions of many social scientists even at the zenith of the vogue of racist thought. Facilitated by the decline of racialist explanations and by an increased sophistication in methodological techniques, social-scientific attention to race and African-American culture steadily increased throughout the twenties and thirties. The convergence of these several currents fostered a climate receptive to efforts to obtain personal testimonies concerning antebellum slave life, and it was from within this cultural milieu that interest in the collection of ex-slave narratives arose.

Collections That Led the Way

The earliest of the endeavors to secure interviews with ex-slaves was initiated in 1929 under private auspices when separate and independent projects began simultaneously at Fisk University, Southern University, and Prairie View State College. The projects at Southern and at Prairie View were directed by John B. Cade, a historian whose interest in using the accounts of ex-slaves was initially aroused by the controversy over the nature of the slave regime and, in particular, by Ulrich B. Phillips’s contention that slaves had been contented with their lot. Cade later summarized the materials collected under his direction at Southern in the article “Out of the Mouths of Ex-Slaves,” and its success stimulated him to undertake a similar effort at Prairie View during the mid-1930s.6

The Fisk collection of slave narratives evolved as an unanticipated consequence of research directed by Charles S. Johnson, who had established the Social Science Institute at Fisk in 1928. One of Johnson’s earliest projects, an extensive community study of the African-American neighborhoods adjacent to Fisk in Nashville, foreshadowed the influence his research training at the University of Chicago’s renowned Department of Sociology was to exert on the Fisk collection of slave narratives. In that study, Johnson’s research design relied heavily on personal interviews, and Ophelia Settle of the Institute’s research staff interviewed a large number of former slaves. Johnson quickly recognized the value of preserving such firsthand accounts of slave life and urged that a concerted effort be made to obtain them. In addition to those in Nashville, interviews were conducted in rural Tennessee and Kentucky and later as an integral component of Johnson’s study of Macon County, Alabama, which formed the substance of his analysis of the plantation as a social institution.7 These interviews proved so satisfactory that Johnson planned to publish a volume based on an analysis of the one hundred documents Settle had obtained. Although the plan was never realized, the Institute’s Unwritten History of Slavery reproduced approximately one-third of the narratives.8

The WPA and the Slave Narrative Collection

The WPA and Americans’ Life Histories

Private efforts to preserve the life histories of former slaves accounted for only a small portion of the narratives collected during the late 1920s and 1930s. The advent of the New Deal marked a new phase, for it was under New Deal employment programs for jobless white-collar workers that narrative collecting reached its zenith, first in 1934 in a Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA) white-collar project headed by Lawrence D. Reddick at Kentucky State College and subsequently in its successor organization, the Works Progress Administration. Both agencies were created in response to the massive unemployment of the Great Depression and were designed to use unemployed workers on public-works projects such as building roads, dams, bridges, and swimming pools. However, the scourge of unemployment during the Depression was not restricted to blue-collar workers, and thus both the FERA and the WPA included projects for white-collar workers as well. The most notable of these were the WPA Arts Projects.

The spirit of innovation and experimentation that was the hallmark of the New Deal was nowhere more clearly manifested than in the establishment of Federal Project Number One, better known as the Federal Arts Project, an umbrella organization that included the Federal Art, Music, Theatre, and Writers’ Projects designed to assist unemployed writers, artists, musicians, and actors by providing them with employment that would use their occupational skills. With the creation of the Arts Project the Federal government embarked upon an unprecedented program of support for artistic and cultural endeavors.

As originally envisioned, the primary task of the Federal Writers’ Project (also known by its initials, FWP) was to prepare a comprehensive and panoramic “American Guide,” a geographical-social-historical portrait of the states, cities, and localities of the entire United States. The original idea of a single multi-volume national guide ultimately gave way to the American Guide Series, composed of a number of state and local guides.

As the Writers’ Project became more firmly established and its research potential more apparent, the scope of its efforts broadened beyond the guides and activities initially associated with them assumed independent significance. Among these was a series of projects manifesting a fresh appreciation for the folk elements in American life, the most innovative of which sought interviews for anthologies reflecting the lives of Americans from many different backgrounds. According to Ann Banks, the result was “the largest body of first-person narratives ever collected in this country.”9 And the collections of folklore, life histories, and materials on African-American life that resulted gave impetus to the collection of slave narratives.

Thus the program and personnel of the Writers’ Project presented a unique opportunity to pursue folklore research on a national basis, and the emphasis upon the collection of folklore materials became one of the project’s most characteristic and productive features. To direct activities in this area, the Writers’ Project recruited John A. Lomax, one of the foremost figures in the development of American folklore. A man whose pioneering efforts in folklore research established him as “the greatest popularizer and one of the greatest field collectors of American folksong,” Lomax was instrumental in identifying and preserving important black folk materials that had previously been overlooked or ignored.10

Lomax’s tenure with the Writers’ Project was relatively brief, but his impact upon it, and especially on the formation of the Slave Narrative Collection, was enduring. His early direction of the project’s folklore research mirrored his personal interest in Southern and rural materials. The interview method of collecting folklore and the corollary emphasis upon the collection of life-history materials, both of which he introduced, became a hallmark of Writers’ Project research. The life-history approach was used not only in the Slave Narrative Collection but in several unpublished Writers’ Project studies, such as the autobiographies of Texas and Kansas range pioneers. It was most fully developed in the highly original and widely acclaimed These Are Our Lives, a series of life histories of a broad and diverse but undistinguished group of residents of the southeastern United States.11 The Slave Narrative Collection was thus a natural and logical extension of the Writers’ Project goal of letting ordinary people tell their own life stories.

The Black Presence in the Writers’ Project

During the Depression, an awakened appreciation for the cultural diversity of the American people heightened interest in and sympathy for American minority groups. The broad egalitarianism of the New Deal both reflected and inspired this attitude. The Roosevelt administration proved more responsive to the needs and interests of African Americans than had anyadministration since Lincoln’s; blacks, in turn, became an important element in the New Deal coalition. Cooperation was fostered by the efforts of a handful of prominent administration spokesmen and by the pressures that African Americans themselves exerted to obtain representation in New Deal programs. Through these efforts, blacks were appointed to positions of responsibility within numerous governmental agencies, creating the “Black Cabinet” or “Black Brain Trust”–a vocal and eloquent group of highly trained and politically astute African-American intellectuals who spearheaded the struggle for civil rights during the thirties. Within the administration, its members served, officially and unofficially, as their agency’s “race relations advisor” and “to look out for the Negro interests.” Discrimination still flourished, for this representation of African Americans in the New Deal was largely token. But compared to the indifference of previous administrations, it was also a significant departure.

African-American participation on the Writers’ Project was achieved only after the lack of black personnel had been scored by black leaders. Following the predictable New Deal pattern, an Office of Negro Affairs was created, which played a vital role in the Writers’ Project program. With “Black Cabinet” support, Sterling A. Brown, a Washington, D.C., poet and Howard University English professor, was enlisted to insure that “the Negro [was] not neglected in any of the publications written by or sponsored by the Writers’ Project.”12

While its primary official responsibilities were editorial, the Office of Negro Affairs also served as watchdog over the Writers’ Project’s personnel practices. In this capacity its course of action was limited because personnel policies were largely determined by the participating states, and the national office could do little more than deplore the discrimination that existed and recommend the addition of qualified black writers. Black participation was in many instances circumscribed by white Southern mores that dictated the establishment of separate units for white and black, the cost of which was often prohibitive. Moreover, state Writers’ Project officials were extremely sensitive to local white public opinion and were reluctant to take any action that might endanger their already tenuous status in the eyes of the white community. When individual African Americans were hired in states lacking separate black units, their terms were often of short duration; the familiar pattern of “last hired, first fired” is amply documented in FWP records.

Yet the record of the FWP on this score is mixed. While African Americans were virtually excluded from Writers’ Projects in several Southern states, the pattern was not universal. In several states–notably Virginia, Louisiana, and Florida–ambitious black units flourished; in several others the number of black workers fluctuated in response to work quotas. And the energies of the black writers were directed almost exclusively to the collection of materials pertaining to African-American culture.

The relative paucity of black personnel on the Writers’ Project makes their accomplishments all the more impressive. In addition to the collection and preparation of materials for the state guides, African-American workers in Arkansas, Louisiana, Florida, and Virginia engaged in research studies on black history and culture. The Washington office of the FWP also contemplated publishing a history of the antislavery struggle “from the Negro point of view”; development of a comprehensive bibliography of writings on African-American culture; and the compilation of a documentary record of events in the history of the Underground Railroad. Sterling A. Brown, whose unstinting support and encouragement sustained each of those efforts, had personally formulated plans for the publication of a volume that would draw substantially upon Writers’ Project materials obtained by black researchers. These studies were curtailed and publication plans based upon them thwarted, however, by the abrupt termination of the Writers’ Project in 1939. Only The Negro in Virginia, a product of that state’s black unit directed by Roscoe E. Lewis and one of the outstanding achievements of the Writers’ Project, attained publication.13

The WPA Begins Collecting Slave Narratives

Preliminary plans for the Writers’ Project made no provision for collecting slave autobiographies, testimonies, and reminiscences. Interviews with former slaves were undertaken spontaneously after the inception of the FWP and were included among the activities of several Southern Writers’ Projects for almost a year before these isolated and unrelated efforts were transformed into a concerted regional project coordinated by the Washington office. Project records reveal that a small number of ex-slave interviews had been sporadically conducted, often by a single black employee, in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia without explicit direction or apparent recognition from Washington before the collection of narratives was officially inaugurated by the national headquarters of the FWP in April of 1937.

It was a group of ex-slave narratives submitted by the Florida Writers’ Project that directly sparked the establishment of a regional study under FWP auspices. The Florida narratives had been independently undertaken under the direction of the State Director of the Florida Writers’ Project, Carita Doggett Corse, who earlier in her career had glimpsed the potential value of such interviews while engaged in research on a history of Fort George Island. When Corse was appointed Director of the Florida Writers’ Project in the fall of 1935, the recollection of her conversations with an aged ex-slave who had vividly recalled much of the island’s past, coupled with the Writers’ Project emphases upon personal history and interview methods of data collection, suggested the possibility of using project personnel to interview ex-slaves. In 1936 employees of Florida’s active black FWP unit, which included the novelist-anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, interviewed a substantial number of former slaves as an integral part of their quest for indigenous African-American folk materials. These activities were nominally associated with the compilation of the Florida Guide and the narratives obtained were later considered for inclusion in a projected volume entitled The Negro in Florida which was never completed.14

In March of 1937 several of the Florida interviews were forwarded to Washington for editorial comment. Lomax and Brown were intrigued by the narratives and immediately recognized the value of preserving them. Excited by the possibilities that the structure and emphases of the Writers’ Project afforded for large-scale collection of life histories, Lomax proposed that such efforts be extended more systematically to the remaining Southern and border states. On April 1, 1937, the collection of slave narratives formally began with the dispatch of instructions to each of these states directing their Writers’ Project workers to the task of interviewing former slaves.

John Lomax’s Leadership and the Issue of Race

The WPA project to interview former slaves assumed a form and a scope that bore Lomax’s imprint and reflected his experience and zeal as a collector of folklore. His sense of urgency inspired the efforts in several states. And his prestige and personal influence enlisted the support of many project officials, particularly in the deep South, who might otherwise have been unresponsive to requests for materials of this type.

One might question the wisdom of selecting Lomax, a white Southerner, to direct a project involving the collection of data from black former slaves. Yet whatever racial preconceptions Lomax may have held do not appear to have had an appreciable effect upon the Slave Narrative Collection. Lomax’s instructions to interviewers emphasized the necessity of obtaining a faithful account of the ex-slave’s version of his or her experience. “It should be remembered that the Federal Writers’ Project is not interested in taking sides on any question. The worker should not censor any materials collected regardless of its [sic] nature.”15 Lomax constantly reiterated his insistence that the interviews be recorded verbatim, with no holds barred. In his editorial capacity he closely adhered to this dictum, making only minor grammatical corrections, never altering the substance of the narratives. Narratives were never rejected or revised because of questions about their authenticity.

On the other hand, while Lomax was keenly sensitive to the importance of establishing adequate rapport with the aged informants, it does not appear that he seriously considered the possibility that black interviewers might accomplish this more effectively than white. Earlier evaluations of the Georgia narratives had reported that black interviewers appeared “able to gain better insight” than whites and that the interviews obtained by blacks were “less tinged with glamour.” Nevertheless, no special attempt was made to assign African Americans to this task, as had previously been done in Georgia, Florida, and several other states. Indeed, after the national office of the FWP began directing the project, the writers employed as interviewers were almost exclusively white–and it is probable that in many instances caste etiquette led ex-slaves to tell white interviewers “what they wanted to hear.” Lomax’s personal success in obtaining African-American folklore may have blinded him to the effects of the interviewer’s race on the interview situation.

Yet Lomax should not be held solely responsible for the paucity of black interviewers, for his duties were editorial rather than administrative. And as noted above, African Americans were underrepresented among the writers in the Writers’ Project primarily because Washington officials were unable to ensure that black personnel be included in local and state FWP units, especially in the South.

How the Narratives Were Compiled

The responses of the FWP’s state units Lomax’s request for ex-slave materials varied. Interviews were conducted in all Southern and most border states, as well as in New York and Rhode Island. Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas sponsored especially productive projects, but the achievement of the Arkansas Project– whose Director, Bernice Babcock, had a special interest in the ex-slave narratives–exceeded that of any other state. Although their brevity often limits their utility, the nearly seven hundred Arkansas narratives constitute almost one-third of the entire collection. One writer alone, Irene Robertson, interviewed 286 former slaves. Yet in this instance, as in many others in the history of the Writers’ Project, plans for publication were frustrated by the termination of the FWP.

Most of the narratives were compiled in 1937 and early 1938. Thereafter, interviewing was curtailed for several reasons. The competing demands of several other FWP projects in addition to the preparation of the Guides meant that the slave narrative project could not continue indefinitely. Uncertainty about the ultimate disposition of the narratives curbed interest as well. Many officials also felt that the repetition that characterized the narratives marked a point of diminishing returns. Finally, many felt-erroneously, it now appears–that the supply of ex-slaves had been exhausted.16 By the spring of 1939 the collecting of ex-slave interviews had ceased.

After interviewing ended, the narratives lay dormant for several years and it appeared that they might be relegated to permanent archival oblivion in their respective states. Upon the termination of the Writers’ Project, however, responsibility for the final disposition of the narratives was assumed by the Writers’ Unit of the Library of Congress Project, which was concerned primarily with the conservation of Writers’ Project materials not intended for publication by the individual states. Approximately 2,300 narratives, as well as a thousand related documents and other “non-narrative materials” (consisting primarily of copies of the following documents: newspaper advertisements of slave auctions and runaways, state laws and bills pertaining to slavery, tax enumerations on slaves,bills of sale, and so forth), were among the materials called in from the states for permanent storage in the Library of Congress.

Benjamin A. Botkin, a noted folklorist who had succeeded Lomax as Folklore Editor of the Writers’ Project, directed the processing of these materials. Botkin was chiefly responsible for preserving the narratives in a permanent collection, for without his sensitivity to the value of this collective portrait and without his concern for their preservation and what could be made of them, the interviews would probably never have been put to use. Appropriately subtitling the collection “A Folk History of Slavery in the United States,” Botkin supervised the accession of the interview materials from the states and their organization into bound volumes that were then deposited in the Rare Book Room of the Library of Congress.17 With the exception of a number of the Virginia narratives used in the preparation of The Negro in Virginia and not forwarded to Washington, all the narratives that had been sent to Washington from state Writers’ Project offices were presented in bound volumes to the Library of Congress in 1941.

Making the Collection Known

The first publication to use the Slave Narrative Collection was the Virginia Writers’ Project’s The Negro in Virginia, which drew on many of the interviews obtained by the Federal Writers to reconstruct the history of slavery in the Old Dominion. Other publications in the 1940s that used or drew inspiration from Writers’ Project interviews with former slaves included the Georgia Writers’ Project’s Drums and Shadows, on the cultural traditions of African Americans along the Georgia coast, and the Louisiana Writers’ Program’s Gumbo-Ya-Ya, a miscellany of Louisiana folklore that is based in part on interviews with former slaves, most of which were obtained after the Writers’ Project had come to an end.18 These works used the collection as primary-source material but the collection itself was not their main focus.

In 1945, the existence of the collection was widely publicized for the first time by Botkin’s Lay My Burden Down, a work that assembled excerpts and selections from the collection that were mainly in the form of anecdotes and folklore. While Lay My Burden Down vividly captures the flavor of the collection’s contents, fewer than twenty of the more than two thousand interviews in the collection were included in it in their entirety.19 Responding to the need to make these materials more widely available, in 1970 I published Voices From Slavery (also published in a text edition under the title Life Under the “Peculiar Institution”), which contains one hundred complete interviews.20

Although Lay My Burden Down and Voices From Slavery publicized the existence of the Slave Narrative Collection, the entire collection still remained relatively inaccessible. This impediment was removed in 1972 with publication of the entire series by Greenwood Press under the title The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, edited by George P. Rawick. As an introduction to the series, Greenwood also published Rawick’s interpretive study of slavery From Sundown to Sunup, which is based almost exclusively upon interviews found in the Slave Narrative Collection. The series also includes two volumes of the interviews obtained under the direction of Charles S. Johnson at Fisk University during the 1920s.21

Discovering More Slave Narratives

Although much has been written about the Writers’ Project, much of its story may never be told.22 This is because most of the research concerning the project has focused upon the activities and objectives of the national office in Washington and has consulted local and state records only infrequently. Yet many of the activities of the state units were undertaken with minimal direction from the national office and when the FWP was terminated, their records and data were hurriedly boxed and stored in local libraries and archives in anticipation of the project’s renewal after World War II. They remained untouched for many years or, in some cases, were destroyed.

Yet as additional WPA and Writers’ Project records at the national and, especially, state levels have been examined, a number of other oral history materials have been discovered. In 1977 and 1979, after Rawick and several other researchers had sifted through many of the voluminous state WPA and Writers’ Project records in libraries and depositories throughout the country, Greenwood Press published two supplementary series to The American Slave totaling twenty-two additional volumes of interviews. Most of these had been collected as part of the Writers’ Project efforts to interview former slaves, but some of them had been obtained in other contexts. Not only did these searches uncover additional narratives that had not been forwarded to Washington, but they also yielded earlier, pre-edited versions of those interviews that were sent from the states to the Writers’ Project national headquarters.23

Such research in local and state archives and libraries has also demonstrated that the Writers’ Project was not alone among New Deal projects in interviewing former slaves. The National Archives houses several excellent interviews that were obtained by workers on the Federal Theater Project. In some states interviews were conducted by workers for the Historical Records Survey. Moreover, in many states there were work projects for white-collar workers apart from the Federal Arts Projects (which included the Art, Writers’, Theater, and Music Projects), and a systematic survey of the records of these projects for possible oral-history materials remains to be undertaken. As additional records of state units of the many WPA agencies are examined, it is likely that they will reveal other valuable oral histories.24

The Limitations of the Slave Narrative Collection

Problems of Memory

Before the resurgence of interest in slavery generated by the Black Protest Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, few historians or social scientists sought to mine the riches of the ex-slave testimonies. One major reason for this neglect was that until 1972 the entire collection was relatively inaccessible. Although the original transcripts were available for reference in the Rare Book Division of the Library of Congress, the collection does not circulate, and its sheer bulk (more than ten thousand unindexed pages) undoubtedly discouraged efforts to use it more widely and effectively.25 Since the early 1970s, however, both the entire Slave Narrative Collection and selections from it have been widely reprinted, and the present effort by the Library of Congress to make the collection available through the Internet now renders that limitation moot.

A more significant reason for the neglect of the Slave Narrative Collection before the 1970s, however, was the circumspection with which historians have generally regarded personal reminiscences. Recollection of the past is always a highly subjective phenomenon, one continually susceptible to modification and distortion. The alleged untrustworthiness of these interviews with aged former slaves has, therefore, been a frequent and not inconsequential objection to their use in historical research. For example, John Blassingame, whose book The Slave Community was a pioneering effort to analyze the personal accounts of former slaves–in this case primarily the antebellum slave narratives–has been especially skeptical of the Slave Narrative Collection interviews, and, although aware of their existence, did not use them in The Slave Community for fear that their use would “lead almost inevitably to a simplistic and distorted view of the plantation as a paternalistic institution where the chief feature of life was mutual love and respect between masters and slaves.”26

Certainly the interviews in the Slave Narrative Collection present problems beyond the general issue of the reliability and accuracy of recollections of the past. Not only had more than seventy years elapsed between Emancipation and the time of the interviews, but most informants had experienced slavery only as children or adolescents. Those interviewed were extremely old and most were living in conditions of abject poverty during the Depression years of the 1930s. These factors often combined to make them look upon the past through rose-colored glasses; they fondly described events and situations that had not been, in reality, so positive as they recalled them. Moreover, it is apparent that some informants, mistaking the interviewer for a government representative who might somehow assist them in their economic plight, replied to questions with flattery and calculated exaggeration in an effort to curry the interviewer’s favor. Exaggeration may often have been the consequence of the interview itself, which gave informants an opportunity to be the center of attention.

It is uncertain, then, whether the former slaves reported their experience under slavery accurately and truthfully. Two other major questions surrounding the use of the slave narratives concern, first, whether the interviewers were able to elicit candid responses from their informants and, second, whether what the informants said was accurately recorded.

It is axiomatic that the quality of an interview depends on the skill of the individual who obtains it. The quality of typewritten accounts contained in the Collection is grossly uneven, reflecting the varied talents of the Federal Writers. Most of the interviewers were amateurs, inexperienced and unsophisticated in the use of interview techniques. Most expressed little concern about the problems of distortion inherent in the interview process and were insensitive to the nuances of interview procedure. A questionnaire devised by Lomax suggesting possible categories of discussion was often partially or totally ignored, frequently resulting in rambling and trivial comments. When the questionnaire was too closely followed, the result was stylized and superficial responses, devoid of spontaneity. Moreover, it is problematic how accurately interviewers wrote down exactly what the informant had said, especially when, as in many narratives, there was great attention given to dialect. In addition, as Rawick’s searches of state Writers’ Project records indicate, some of the writers and editors themselves undertook to revise, alter, or censor the accounts.27

Race and Representativeness

It is probable that the interviewer’s race affected an informant’s response. As noted earlier, the staffs of the Writers’ Projects in the states in which former slaves were interviewed were overwhelmingly white. The relative absence of black interviewers introduced an important source of bias, for the interviewer’s race was a significant factor in eliciting responses from the former slaves. The etiquette of Southern race relations influenced the definition of the interview situation for these aged African Americans, and some of their interviewers were even members of the former slaveholding families. As a result, informants may frequently have told their white interviewers “what they wanted to hear.” For similar reasons many were undoubtedly less than fully candid or refused to tell a complete story, resulting in a kind of self-censorship.

Fortunately, some black interviewers were involved in obtaining the narratives, and it is therefore possible to assess the influence of race by comparing the responses of those interviewed by whites with those of people interviewed by blacks. For example, in a systematic analysis of the Slave Narrative Collection and similar interviews obtained earlier by Fisk University interviewers, Paul D. Escott found that 72 percent of the ex-slaves interviewed by whites rated the quality of their food as good, while only 46 percent of those interviewed by blacks did. Similarly, 26 percent of those responding to white interviewers expressed unfavorable attitudes toward their former masters compared to 39 percent of those who responded to black interviewers.28

However, it is important to recognize that distortion is not something inherent in the interview situation, but is relative to the specific questions asked by the researcher. There are questions and issues that were not affectively charged by the race of the interviewer. For example, in a systematic analysis of family patterns in the ex-slave interviews, Herman R. Lantz found no evidence that the race of the interviewer affected the overall reporting of family relationships.29 Therefore, depending upon how unobtrusive or subtle the measures used by the researcher, how much the race of the interviewer affected responses is an open question.

Another problem surrounding the Slave Narrative Collection concerns the representativeness of the informants. Despite the large number of interviews obtained by the Writers’ Project, less than two percent of the available ex-slaves were interviewed. This in itself is not an insurmountable problem, except that it has been impossible to determine the processes by which informants were selected. There appears to have been little concern in the Writers’ Project for systematic sampling procedures or for obtaining a representative sample of the former slaves, since the problem is nowhere mentioned in the project’s extensive correspondence. The skew of the sample can be seen simply in the following figures: while blacks over eighty-five years of age lived primarily in rural areas in the 1930s, those whose accounts are found in the collection were overwhelmingly urban residents. Apparently the primary basis for selection was availability; those in closest proximity to the cities in which the Federal Writers were based were most likely to be interviewed. Finally, the number of interviews obtained by each of the participating states varied considerably, ranging from three in Kansas to nearly seven hundred in Arkansas.

Should the Slave Narrative Collection Be Used?

Given the myriad problems of authenticity and reliability surrounding the interviews, one might despair of using them at all. Indeed, until the 1970s they were not widely used in a serious fashion by scholars. The reservations concerning their use were summarized by David Henige, who, after a cursory discussion of the context within which the interviews were obtained, concludes that “the combination of weaknesses that characterizes the ex-slave narratives restricts their reliable data to such matters as childhood under slavery, some aspects of family life, some details on slave genealogies, and some unintended insights into the nature of memory and of interview psychology….” Therefore, he contends, the Federal Writers’ Project effort to preserve the life histories of the former slaves “was largely an opportunity lost.”30

However, a blanket indictment of the interviews is as unjustified as their indiscriminate or uncritical use. Each kind of historical document has its own particular usefulness as well as its own inherent limitations for providing understanding of the past. The utility of the ex-slave interviews can only be determined in the context of the objectives of the researcher. For example, if one is interested in entering the perennial debate over the profitability of slavery, information obtained from the narratives will be highly impressionistic and much less valuable than that from other sources such as plantation records. Yet if one wishes to understand the nature of the “peculiar institution” from the perspective of the slave, to reconstruct the cultural and social milieu of the slave community, or to analyze the social dynamics of the slave system, then these data are not only relevant; they are essential. That is not to imply that they should be used exclusively or without caution. Yet the hazards of attempting to comprehend slavery without using them far outweigh the limitations of their use.31 Saidiya V. Hartman has recently undertaken a penetrating assessment of the Slave Narrative Collection’s utility. With all their limitations, she asks,

How does one use these sources? At best with the awareness that a totalizing of history cannot be reconstructed from these interested, selective, and fragmentary accounts and with an acknowledgment of the interventionist role of the interpreter, the equally interested labor of historical revision, and the impossibility of reconstituting the past free from the disfigurements of present concerns. With all these provisos issued, these narratives nonetheless remain an important source for understanding the everyday experience of slavery and its aftermath…. I read these documents with the hope of gaining a glimpse of black life during slavery and the postbellum period while remaining aware of the impossibility of fully reconstituting the experience of the enslaved.32

The Importance of the Slave Narrative Collection

Elsewhere I have described the dramatic impact that knowledge of the Slave Narrative Collection has had on the subsequent revitalization of African-American history and, particularly, on the study of American slavery.33 The outpouring of scholarship on slavery represents a dramatic shift in American historiography. Though several major works on the topic appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, since the late 1960s the study of slavery has engaged many of the most prominent and able of American historians. As David Brion Davis, one of the most distinguished of these scholars, wrote in 1974 at what then appeared to be the height of scholarly examination of the “peculiar institution,” “the institution of slavery has now been probed at every spot, often with passionate intensity, and the explosive debates have left few questions settled.”34

In large measure this surge of interest was stimulated by the Black Protest Movement of the 1960s and 1970s and its challenge to examine critically the roots of the racial inequalities that have pervaded and degraded American life. It also coincided with the emergence in the 1970s of the “new social history,” as historians expanded both the sources of data and the methods they used to reconstruct the past and shifted their focus from the study of elites to the study of the lives of formerly anonymous Americans. History written “from the bottom up”–from the perspectives of the unlettered, the undistinguished, the powerless–became increasingly fashionable.

Evidence from slave sources–most important, the Slave Narrative Collection interviews–has been a critical ingredient in this surge of scholarship. The Slave Narrative Collection has not only provided a wealth of previously unexploited data on the institution of slavery, but it has also responded to the interests of the proponents of the “new social history” for data that would reflect the perspectives of the voiceless masses who seldom left written evidence from which to write their history. Indeed, in 1974 Davis called the availability of an abundance of ex-slave testimonies in published form one the five major “turning points” in the post-World War II historiography of slavery and predicted that they would be indispensable to future studies of the subject.35

Yet not even Davis could have anticipated the profusion of scholarship that has borne out his prediction: in a voluminous range of literature published since the early 1970s, the published ex-slave interviews have been the single most important source of data used to examine the “peculiar institution” and its impact.36 Thus the comprehension of American slavery has been enhanced immeasurably by these testimonies. Without the personal accounts of former slaves, any attempt to present an account of slavery or to comprehend the reality of slave culture, especially from the slave’s perspective, would have lacked a crucial ingredient. The ex-slave interviews are not the only source with which to reconstruct the slaves’ experience of slavery, but they have become indispensable to comprehending it. Although the questions, interpretations, and conceptual frameworks with which historians approach the phenomenon of American slavery may change, these data will continue to remain essential to their endeavors.

Endnotes

- For the sake of brevity, I have omitted many references in this essay. More extensive and detailed discussion and documentation can be found in two articles that I have previously published on which I have drawn substantially in my discussion here: “The Background of the Slave Narrative Collection,” American Quarterly 19, no. 3 (Fall 1967), 534-53, and “Ex-Slave Interviews and the Historiography of Slavery,” American Quarterly 36, no. 2 (Summer 1984), 181-210. © The American Studies Association. Reproduced with permission of the Johns Hopkins University Press.

- David Brion Davis, “Slavery and the Post-World War II Historians,” Daedalus 103 (Spring 1974): 7.

- George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society (Richmond, Va., 1854), 246.

- Ulrich B. Phillips, American Negro Slavery, A Survey of the Supply, Employment, and Control of Negro Labor as Determined by the Plantation Regime (New York, 1918; reprint Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1996).

- Stanley M. Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (Chicago, 1959), 11.

- John B. Cade, “Out of the Mouths of Ex-Slaves,” Journal of Negro History, XX (July 1935).

- Charles S. Johnson, Shadow of the Plantation (Chicago, 1934); see also E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago, 1939).

- The Fisk University interviews were originally published in mimeographed form: Ophelia Settle Egypt, J. Masuoka, and Charles S. Johnson, Unwritten History of Slavery: Autobiographical Accounts of Negro Ex-Slaves (Nashville, 1945). A second volume, Fisk University Social Science Institute, God Struck Me Dead: Religion Conversion Experiences and Autobiographies of Ex-Slaves (Nashville, 1945), was also part of this project and was published at the same time. Both documents have been reprinted as volumes 18 and 19, respectively, of George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, Conn., 1972-79). God Struck Me Dead has also been reprinted by Clifton H. Johnson, ed. (Philadelphia, 1969).

- Ann Banks, ed., First Person America (New York, 1981), xiii.

- Donald K. Wilgus, Anglo-American Folksong Scholarship Since 1898 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1959), 157.

- Federal Writers’ Project, These Are Our Lives (Chapel Hill, N. C., 1939). In 1978 Tom Terrill and Jerrold Hirsch published a sequel, Such As Us: Southern Voices of the Thirties (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1978), which was drawn from the same materials. Twenty-eight Alabama life histories from Writers’ Project materials have also been reprinted in James Seay Brown, Up Before Daylight: Life Histories from the Alabama Writers’ Project, 1938-1939 (University, Ala., 1982). The most comprehensive of the works using these life histories is Ann Banks’s First Person America (1981), which emphasizes the nation’s occupational, ethnic, and regional diversity during the thirties.

- Eugene C. Homes, Assistant Editor for Negro Affairs to the Editor, The Spokesman, San Francisco, April 10, 1938, Negro Studies File, Record Group 69, National Archives; Sterling A. Brown to author, interview, July 20, 1965.

- Virginia Writers’ Project, The Negro in Virginia (New York, 1940). Roscoe Lewis evinced a keen interest in the tales of former slaves, both in this and in his later research activities. His efforts to obtain slave narratives continued after the Writers’ Project was terminated. At the time of his death in 1961 he had begun a systematic analysis of the more than two hundred life histories he had collected.

- In 1993 Gary W. McDonogh edited The Florida Negro: A Federal Writers’ Project Legacy (Jackson, Miss., 1993), a previously unpublished product of the Florida Writers Project, which relied extensively on interviews with African Americans.

- “Supplementary Instructions #9E to the ‘American Guide Manual.'” April 22, 1937. Records of the Library of Congress Project, Writers’ Unit, NA.

- In fact, the number of individuals whose accounts are found in the Slave Narrative Collection represented approximately 2 percent of the total ex-slave population in the United States at that time. See Yetman, “The Background of the Slave Narrative Collection,” 534-35.

- The “non-narrative materials” that accompanied the interviews were deposited in the Library of Congress’s Archive of Folk Song.

- Georgia Writers Project, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes (Athens, Georgia, 1940; reprint Athens, 1986). Selecting the “most revealing, valuable, and reliable” of the Georgia Narratives, in 1973 Ronald Killion and Charles Waller reprinted eighteen complete interviews and fragments from fifty others in their Slavery Times When I Was Chillun Down on Marster’s Plantation (Savannah, Georgia, 1973). Lyle Saxon, comp., Gumbo Ya Ya: A Collection of Louisiana Folk Tales (Boston, 1945); see also Ronnie W. Clayton, Mother Wit: The Ex-Slave Narratives of the Louisiana Writers’ Project (New York, 1990). Louisiana was the only Southern state not to participate in the Writers’ Project ex-slave study, but interviews with former slaves were conducted in Louisiana after the termination of the Writers’ Project.

- Benjamin A. Botkin, Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery (Chicago, 1945; reprint Athens, Georgia, 1989; New York, 1994).

- Norman R. Yetman, Voices From Slavery and Life Under the “Peculiar Institution”: Selections from the Slave Narrative Collection (New York, 1970; reprint Melbourne, Florida, 1976; Mineola, N.Y., 2000). See also Julius Lester’s To Be a Slave (New York, 1968; reprint, 1998), a brief interpretive and documentary history of slavery in the United States.

- Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography; From Sundown to Sunup: The Making of the Black Community is the first volume of this work. In addition to the separate volumes of ex-slave interviews from Georgia, Florida, and Louisiana noted above, books containing interviews obtained by members of the Texas, North Carolina, and Oklahoma Writers’ Projects have been published. See Ronnie C. Tyler and Lawrence R. Murphy, The Slave Narratives of Texas (Austin, 1974), which contains edited excerpts from slightly more than one-third of the 308 Texas interviews found in the Slave Narrative Collection; Belinda Hurmence, My Folks Don’t Want Me to Talk About Slavery: Twenty-One Oral Histories of Former North Carolina Slaves (Winston-Salem, N.C., 1984); and T. Lindsey Baker and Julie P. Baker, eds., The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives (Norman, Oklahoma, 1996).

- Jerre Mangione, The Dream and the Deal: The Federal Writers’ Project, 1935-1943 (Boston, 1972); Monty Noam Penkower, The Federal Writers’ Project: A Study in Government Patronage of the Arts (Urbana, Illinois, 1977); William F. McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration (Columbus, Ohio, 1969).

- George P. Rawick, Jan Hillegas, and Ken Lawrence, eds., The American Slave, Supplement Series 1, 12 vols. (Westport, Conn., 1977); Rawick, The American Slave, Supplement Series 2, 10 vols. (Westport, Conn., 1979). For an index to all forty-one volumes of The American Slave, see Donald M. Jacobs, The Index to the American Slave (Westport, Conn., 1981).

- See, for example, Charles Orson Cook and James M. Poteet, eds. “‘Dem Was Black Times, Sure ‘Nough’: The Slave Narratives of Lydia Jefferson and Stephen Wiliams,” Louisiana History 20 (Summer 1979): 281-92.

- By the 1960s a microfilm version of the collection had become available.

- John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Ante-Bellum South (New York, 1972; revised edition 1979); John W. Blassingame, “Using the Testimony of Ex-Slaves: Approaches and Problems,” Journal of Southern History 41 (1975): 490. For a critical assessment of The Slave Community, see Al-Tony Gilmore, ed., Revisiting Blassingame’s “The Slave Community”: The Scholars Respond (Westport, Conn., 1978). A substantially expanded version of Blassingame’s detailed critical assessment of different forms of personal testimonies, particularly the Slave Narrative Collection interviews, serves as the introductory essay for his Slave Testimony (Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1977), an exhaustive compilation of letters and speeches of slaves and former slaves; interviews conducted by journalists, scholars, and government officials; and autobiographies. Fears that the ex-slave interviews would be accepted at face value and used uncritically recently surfaced in North Carolina, where the state N.A.A.C.P. challenged a community college course taught by local members of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, who contended that, based on their analysis of Slave Narrative Collection interviews, “70 percent of slaves were satisfied with their lives in captivity.” “Class Teaches That Slaves Were Happy,” New York Times, November 16, 1998, A15.

- Rawick, The American Slave, Supplement Series 1 and 2. See especially Rawick’s comments comparing earlier versions of Texas interviews with those that were finally sent to Washington for inclusion in the Slave Narrative Collection. Most of the material deleted from later versions did not conform to the prevailing white notions of proper race relations and racial etiquette. Rawick, The American Slave, Supplement Series 2, 1: xxx-xxxix.

- Paul D. Escott, Slavery Remembered: A Record of Twentieth-Century Slave Narratives (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1979).

- Herman R. Lantz, “Family and Kin as Revealed in the Narratives of Ex-Slaves,” Social Science Quarterly 60 (1980): 670.

- David Henige, Oral Historiography (London, 1982), 117,118.

- For critical assessments of the utility of the ex-slave interviews, see Rawick, From Sundown to Sunup, xviii-xix; Escott, Slavery Remembered, 6-17; Rawick, The American Slave, Supplementary Series 1, 1:xix-xli, lxxxvi-cvi; Yetman, Voices From Slavery, 3-4; C. Vann Woodward, “History from Slave Sources,” American Historical Review 79 (1974): 470-81; Eugene D. Genovese, “Getting to Know the Slaves,” New York Review of Books, 19, 21 Sept. 1972, pp. 16-19; Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York, 1974), 676; Thomas F. Soapes, “The Federal Writers’ Project Slave Interviews: Useful Data or Misleading Source,” Oral History Review 2 (1977): 33-38; David Thomas Bailey, “A Divided Prism: Two Sources on Black Testimony on Slavery,” Journal of Southern History 46 (1980): 381-404; Donna J. Spindel, “Assessing Memory: Twentieth-Century Slave Narratives Reconsidered,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 27 (1996): 247-61; Herbert C. Covey and Paul T. Lockman Jr., “Narrative References to Older African Americans Living Under Slavery,” Social Science Journal 33 (1996): 23-37.

- Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York, 1997), 11.

- Yetman, “Ex-Slave Interviews and the Historiography of Slavery,” American Quarterly 36, no. 2 (Summer 1984): 181-210 and the Preface to the Dover Edition of Voices From Slavery (2000).

- Davis, “Slavery and the Post-World War II Historians,” 2, 7.

- Charles S. Johnson, Shadow of the Plantation (Chicago, 1934); see also E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago, 1939).

- The task of reviewing that extensive literature is well beyond the scope of this introductory essay, but let me suggest, in addition to those already mentioned, some of the most important of the numerous books that have effectively incorporated materials from the Slave Narrative Collection into their analyses: Rawick, From Sundown to Sunup (1972); Gladys-Marie Fry, Night-Riders in Black Folk History (Knoxville, Tenn., 1975); Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll (1974); Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (New York, 1976); Ollie Alho, The Religion of the Slaves: A Study of the Religious Tradition and Behavior of Plantation Slaves in the United States, 1830-1865 (Helsinki, 1976); Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought From Slavery to Freedom (New York, 1977); Thomas L. Webber, Deep Like the Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community, 1831-1865 (New York, 1978); Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (New York, 1978); Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York, 1979); Escott, Slavery Remembered (1979); William L. Van Deburg, The Slave Drivers: Black Agricultural Labor Supervisors in the Antebellum South (Westport, Conn., 1979); Charles Joyner, Down by the Riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community (Urbana, Illinois, 1984); Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (New York, 1988); Katrina Hazzard-Gordon, Jookin’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture (Philadelphia, 1990); Roger D. Abrahams, Singing the Master: The Emergence of African-American Culture in the Plantation South (New York, 1992); Ann Patton Malone, Slave Family and Household Structure in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1992); John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1993); Wilma King, Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America (Bloomington, Ind., 1995); Hartman, Scenes of Subjection (1997); Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, Mass., 1998). The quintessential fictional use of the slave narrative form is Ernest Gaines’s epic novel The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (New York, 1971).

Originally published by the Library of Congress to the public domain.