People selectively perceive inequality from among all its manifold forms.

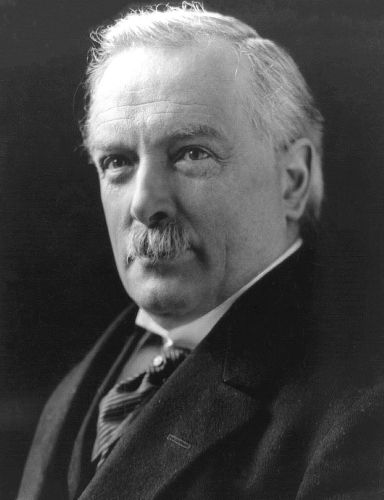

By Dr. Simon Szreter

Professor of History and Public Policy

Fellow, St. John’s College

University of Cambridge

Abstract

After reviewing evidence on long-run national trends in inequality since the 1320s and the history of ideas and measures of inequality, the focus is on the history of institutions which have influenced the trends in inequality. Here, the major surprise for many will be to learn that a progressively funded universal social security, health and welfare system was instituted by Elizabeth I in 1601. The welfare state was not invented but restored by the Labour government of 1945–51, decreasing inequalities substantially. In 1834, the parliament had reduced the Elizabethan Poor Law to a deterrent workhouse system, its funding halved in accord with the ideas of Bentham, Malthus and economic liberalism. Since 1979, the successor ideology of neo-liberalism has again increased inequality by reducing the progressivity of taxes and restraining expenditure on public services. After 1979, child poverty more than doubled to over 30% and has never returned to previous lower levels.

Introduction

In its initial report, the IFS Deaton Review pointed out that ‘[i]nequality cannot be reduced to any one dimension: it is the culmination of myriad forms of privilege and disadvantage, many of which reinforce each other’.1 This historical commentary will discuss the influence of the most significant institutions that have produced these interacting dimensions in British history, after first summarizing what is currently known of long-term historical trends in income and wealth inequality.

The longest-run trends available are for estimates of wealth inequality, as reasonably reliable registers of land (the main form of wealth before the industrial revolution) and tax records can be analysed for a number of European states (though not for Britain before 1670). The research by Alfani (2021) shows a steep decline in wealth inequality across the century c.1340–1440 after the Black Death (1348–49). This was followed by a steep rise in wealth inequality 1440–1540 back to the levels prevailing before the Black Death. Alfani and Garcia Montero (2021, Table 6) provide separate estimates for England in 1327–32 and in 1524–25, based on analysis of the lay subsidies, which indicate that, similarly to the rest of western Europe, by the latter years, inequality had returned to the same level as in the former years with 64% of wealth in the hands of the top 10% by 1524–25 (equivalent to a Gini coefficient of 0.756).

When we can next pick up the story for the UK, the research of Lindert (1986) offered a central estimate that about 82.7% of wealth was in the hands of the top 10% in 1670, implying further significant growth in inequality since c.1525.2 When it is next measured in 1740, there had been still further increase in inequality since 1670. However, the most recent research by Piketty (2020) indicates that at some point after 1740 there was a fall in overall wealth inequality, which is likely to have been under way some time before 1780 and which then continued down until 1800, by which time it was below the levels of 1740. From 1800 onwards, however, wealth inequality began once again to rise markedly, eventually surpassing all previous estimates at its historic peak, 1900–10.

Piketty (2020) has also been able to provide more distributional detail for the two most recent centuries, as shown in his Fig. 5.4. His estimates show that 1780–1800 saw a slight decline (from 89% to 86%) in the wealth proportion of the top 10% of private property holders, and an equivalent significant rise (from 10% to 13%) in the wealth held by the ‘middle 40%’, with the bottom 50% remaining at little more than 1%.3 However, if there had been any slight reduction in the wealth elites’ share in the second half of the 18th century, Piketty finds that this went into reverse for the whole of the 19th century, with wealth of the top 10% property holders peaking in 1900–10 at an all-time historic high of 94%—of the wealth of the richest state and largest empire on the planet! Indeed, the top 1% held 70%. From that date, however, the wealth of the top 10% began a gradual (1910–42) and then precipitate (1942–90) decline. By 1990, their share of national wealth had been almost cut in half to 48%, while the share of the ‘patrimonial middle class’—the next 40%—had risen to 42%. Even the lowest 50% now had a 10% share in the nation’s wealth, while the top 1% had ‘only’ 18%. Thus, the ‘short 20th century’, 1910–90, truly was an era of wealth equalization on a scale never before seen, affecting even the top 1%, who saw their share of the nation’s private wealth reduced from 70-fold to just 18-fold relative to their numbers. However, as is well known, income inequality has once again risen sharply since 1980, and this has already begun to show up also in wealth inequality, with the top 10% holding 54% by 2015, and the top 1% back up to 20%. The patrimonial middle class has meanwhile declined back to 40%; and the bottom 50% has also fallen back to 8%. Recent research from the Resolution Foundation has also tracked down £800 billion in wealth held by the top 1% of households, which was missing from official statistics, indicating that in 2020 their share was in fact standing at 23% (Advani et al. 2020).

Where income inequality is concerned, Bob Allen has recently published a careful re-working of the earliest available data from the 1680s to reconstruct aggregate estimates of long-term historical trends (Allen 2019, esp. pp. 110–12). His conclusions are that in the 1680s the upper 20% of the population probably received 50% of the national income (Gini coefficient of 0.54) and that this remained the case until the 1750s. However, a rapidly steepening rise in inequality occurred across the second half of the 18th century, between property-less labourers and those possessing land or commercial capital. By c.1800, the wealthiest 20% had increased their share of all income to 65% (Gini coefficient of 0.60) and this level of extreme income inequality prevailed until 1850.4 It was not until the third quarter of the 19th century that, for the first time, the trend of rising income inequality went into abeyance and even slightly fell back from its peak level, such that by c.1870 the Gini had dropped to 0.48 and remained at that level—somewhat less unequal than in the 1680s—until 1914.5 During the period 1914–79, income inequality then entered a period of sustained reduction, reaching the lowest Gini value of 0.24 by c.1979. It then climbed rapidly back to 0.34 by 1990 and has hardly deviated since (Cribb et al. 2018).

In the following sections, I provide a complementary historical perspective to that of Professor Allen’s. Where his article in this collection focuses on earned incomes and the labour market, investment and productivity, I will first briefly review the importance of the history of ideas and measures and then focus on three other key socio-political factors. Firstly, I will review the progressively tax-funded system of social security and health care. As the government’s own publications show, although they may not appear in measures of income and wealth inequality, the universal benefits in kind of the NHS and of education were, in 2017, worth 60.9% of the disposable income of the poorest one-fifth of the population—but only 8% of the richest one-fifth (Tomlinson 2020, p. 530). As we will see, the history of welfare provision has a far longer history in England and Wales than is often appreciated. Secondly, I will examine the nature of the changing provision made for education and training, where, once again, extremely long-term historical influences are more important than is sometimes appreciated. Thirdly, there is the issue of the changing political voice and powers of land, capital and labour, a subject that includes but is rather wider than the history of parliamentary representation and the suffrage. Finally, the conclusions will reflect on policy implications in the new era post–COVID-19.

Ideas and Measures

It matters how people—including those with the power in government to do something about it—selectively perceive inequality from among all its manifold forms. The historical measures of trends in economic inequality, summarized above, retrospectively apply analytic concepts and measures unknown to early modern British society. These are just some of the possible measures available today, adapted to the availability of long-run historical source materials. The concept of ‘inequality’ itself has a complex history (Béteille 1972; Christiansen and Jensen 2019)—as also do the increasingly sophisticated measures down to today’s incisive Palma ratio.6

Inequality today is often associated with the important concept of ‘intersectionality’, first theorized by Crenshaw (1989). This refers to the ways in which different forms of identity-related discrimination can often overlap and amplify their effects, engraining and deepening inequalities of gender, caste, sex, race, class, sexuality, religion, disability, physical appearance. In the health equity field, the approaches of Richard Wilkinson and Sir Michael Marmot extend this approach to inequality through addressing its multiple dimensions: the material, the social and the cultural (Wilkinson 1996; Marmot et al. 2020a). In the international development field, though it is explicitly not a measure of inequality, the United Nation’s Human Development Index (HDI) is also an attempt to embrace multiple dimensions of human flourishing (or its absence), beyond a reductively economic formulation. The HDI is derived from a conceptualization of human development as relating to differences in the entitlements, capabilities and functionings of individuals within a national polity, as formalized by Sen (1981, 1985); see also Stanton (2007). This is a philosophically rigorous elaboration of the ideas implicit in the United Nation’s approach to human rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 19487, which shared affinities with T. H. Marshall’s celebrated essay, ‘Citizenship and Social Class’, setting out the responsibilities a democratic state has for its citizens’ welfare (Marshall 1950). Marshall in turn was influenced by R. H. Tawney’s influential essay, ‘Equality’ (Tawney 1931; Jackson 2007). Thus, concepts and issues of inequality can be seen as closely related to political and constitutional ideas regarding the ways in which societies are—or are not—set up to promote all of their citizens’ potentials for human development. Twentieth century thought can, in turn, be seen as a culmination of ideas first propounded two or even three centuries earlier. John Rawls’ 1971 A Theory of Justice stands as the most influential and fully developed philosophical statement of this position.8

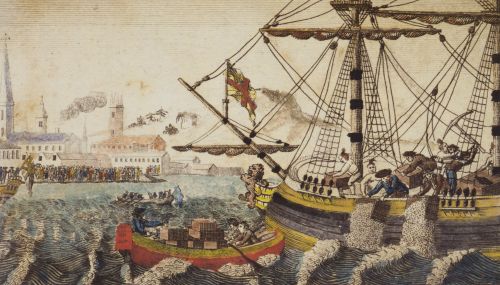

For millennia, the phenomenon of inequality, typically entailing subsistence precarity for many and freedom from subsistence insecurity for a minority, was simply seen as the unavoidable condition of human existence, rationalized by a ‘trifunctional’ ideology, according to which the twin ruling classes of religious and military leaders exercised exclusive property rights and legitimate control over the third group, the labouring masses (Piketty 2020, p. 5). That was until Enlightenment thinkers and the revolutionary movements they inspired on both side of the Atlantic in the late 18th century aspired to end this state of affairs (Stedman Jones 2008). Their proprietarian ideology claimed that universal property rights should be open to all, with a neutral state, elected by all, holding the ring of justice and defence. This ambitious ideal was immediately overwhelmed, however, by the social consequences of the competitive, capital-accumulating processes unleashed in the world-transforming industrial revolution, which created a new, oppressed category of ‘free’ but property-less wage labour, as first critically analysed by Karl Marx (Stedman Jones 2016).

Britain was the geographic epicentre of this maelstrom during the first half of the 19th century, producing an upsurge in destitution, poverty and early death in villages, towns and cities (Pooley and D’Cruze 1994; Szreter 2005, chapter 6). The dominant cultural response to the rising social inequalities was a religiously infused moralizing and individualist interpretation (Hilton 1988). The better-off ‘deserved’ their lot to the extent that they exhibited the virtues of independence and self-help, meaning a god-fearing work ethic of diligence, perseverance and self-denying thrift (Smiles 1859). The poor, stigmatized by the label ‘paupers’, equally deserved their lot, for the lack of these virtues, accused of indulging in laziness, impulsiveness and ungodly intemperance. The most debauched—the poorest—needed the harsh discipline of the workhouse to restore their work ethic. With the subsequent rise of biological science, this moralizing individualism acquired during the first half of the 20th century a further, eugenics-inspired conviction that the nation’s social hierarchy reflected a natural hierarchy—a distribution of ‘innate ability’ passed between families across generations. Though never an accepted consensus, this view had considerable influence over the initial design of the nation’s post–World War II education system, discussed below.

Nevertheless, there were always alternative views of inequality: radicals such as Thomas Paine, feminists, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, socialists, such as Robert Owen, and of course, Marx and Engels (Taylor 1983; Stedman Jones 2008, 2016). There were also those who worked at providing the earliest rigorous social scientific measures of inequality (Yeo 1996). In an era when comprehensive reliable economic data were lacking, the most impressive of these efforts addressed the mortality data generated by the nation’s new civil registration system initiated in 1837. In the hands of William Farr, the pioneer of comparative epidemiology, and his successors as the medical analysts of the demographic data collated by the General Register Office (GRO), a barrage of official publications, beginning in 1838, demonstrated year after year the extraordinary inequalities in health and mortality being experienced across the nation, with labouring families in industrial cities paying a very high price, up to half of their children dying before reaching age 5 years (Eyler 1979). Farr’s ‘public health’ analysis cut right across the individualist moralizing views, in that its explicit goal was to mobilize the relevant urban governing authorities to redress this tidal wave of ‘preventable deaths’ (Szreter 2005, chapter 8). Ultimately, a movement of municipal ‘gas and water socialism’ was launched in the 1870s, once working men finally began to acquire the vote (Szreter 2005, chapter 7; Aidt et al. 2010). When in the early 20th century, the GRO devised an official ‘social class’ model, which was used throughout the rest of the 20th century to analyse how the inequalities of life and death were correlated with social status (Szreter 1984, Szreter 1996, part II), it also—inadvertently—gave support to the view of the nation as a unidimensional hierarchy of intellect, income and wealth, later influencing education policy.

During the second half of the 20th century with the rise to prominence in public policy matters of the discipline of economics, direct measures of income and wealth inequality became more prominent. However, in the 1980s, following the early work of Kuznets (1955) and Atkinson and Harrison (1978), neoliberal governments, economists and even social scientists on both sides of the Atlantic increasingly professed indifference to mere matters of ‘distribution’, so long as per capita GDP continued to grow (O’Connor 2002; Tomlinson 2020). Atkinson lived long enough, however, to see the issues of inequality and distribution return to the top of the agenda following the 2008 financial crash, publishing a powerful epilogue to his career (Atkinson 2015), alongside Piketty’s galvanizing best-seller, ‘Capital in the Twenty-first Century’ (Piketty 2014). Amid a profusion of critical studies, Piketty has also published a substantial follow-up, focusing on the role throughout history of ideologies in justifying regimes of inequality. He argues that the ‘neo-propietarian’ ideology (fetishizing private ownership) of the current neoliberal policy regimes must be overturned, as it is entirely unable to resolve the two, linked existential crises of the 21st century—because they are of its own making: inequality and environmental deterioration (Piketty 2020, p. 46 and chapter 13). The important issue of ideologies relates to the politics of power, to which we return below.9

Social Security, Health Care, and Progressive Taxation

Piketty’s proposed solution to the critical pass that humanity had reached in 2020 envisages a central importance for progressive taxation to prevent ever-escalating inequalities. This also promotes respect and empathy between citizens while fully funding universal public services a dignified way (Piketty 2020, pp. 461–2, 981–8).

What is intriguing and surprising about British history is that, in fact, an enduring regime of this kind was first brought into being from 1601 in England and Wales by Elizabeth I.10 The English Poor Law has been hidden from history due to a succession of efforts to denigrate it, starting with the infamous hanging judges who sat on the 1834 Poor Law Commission, which brought this Elizabethan system to an end and replaced it with the notorious deterrent workhouses of the Victorian Poor Law (Brundage 1978; Charlesworth 2010, pp.16–20).11

In the ‘trifunctional’ era (nobility, clergy, commoners) that preceded the reign of Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII, inequality was viewed throughout Christendom as something divinely ordained, as was the entire cosmos, of course. There were pious obligations of mercy and charity to be performed by the clergy towards the poor and the suffering. Then in 1534, by Henry VIII’s Act of Supremacy, the kingdom of England and Wales joined the protestant movement, splitting from Rome. Creating the Anglican national Church with the monarch at its head, the entire Catholic edifice was dismantled, with the confiscated lands from abbeys and monasteries sold off to private landlords to fund Henry VIII’s expansionary wars (Ellis and Maginn 2007, pp. 127–31.)

A particular dilemma ensued for the English Crown. Having declared itself the spiritual as well as the temporal head of the nation, now synonymous with the Anglican faith, the monarch became ultimately responsible for the way in which all missions of mercy and charity—formerly dispensed by the Catholic Church—were to be organized and delivered. However, the resources with which to fund this had been sold off. Early modern populations were subject to regular harvest failure and repeated attacks of plague, fevers, agues and many other diseases of flora and fauna. The capacity to offer at least some support to the vulnerable was a very big deal. Without it, a monarch could fall in an instant, if unrest in times of hardship should turn into sedition and discontented risings, perhaps exploited by one’s Catholic dynastic enemies waiting in the wings (i.e. France or Spain). This threat was never far away for Elizabeth I throughout her long reign, repulsing the Armada in 1588.

The Tudor Crown’s solution to this self-created predicament was to prove of fundamental importance to the subsequent history of inequality in Britain. In the course of the period 1536–1662, by a process of trial and error, the English state gradually perfected the world’s first effective universal social security system (Slack 1990). Indeed, by the second half of the 18th century, it had developed and matured into a wide-ranging proto-welfare state, including provision of health care services (Williams 2011, pp. 161–2; King 2018).

By far, the most important stage in this process was an Act of 1601 establishing the ‘Elizabethan’ or ‘Old’ Poor Law. The Act decreed that every subject of the Crown was absolutely entitled, without exception, to community support when in need (Charlesworth 2010, ch.3). The Act specified that widows, the old, the ill, the disabled, orphans and the involuntary unemployed were all to be given ‘relief’. Each and every one of the approximately 10 000 parishes (average population of 400 persons) of the Anglican Church was mandated to provide financial support for its poor and vulnerable. It was funded by progressive taxation on the value of land occupied by parishioners. Parishioners were to take turns voluntarily administering the system and their efficiency and probity was legally overseen by Crown-appointed Justices of the Peace, whose decisions were in turn monitored by higher circuit judges. The Anglican parish thereby became the primary administrative unit of a highly devolved ‘welfare state’.

Without doubt, this nationwide system of social security was initially variable in the rapidity of its uptake and the efficiency of its operation. However, from the 1660s—after the Settlement Acts specified the rules of parish liability for mobile subjects—right through to 1834 historians are agreed that copious documentary evidence attests to its ubiquitous operation (Taylor 1989; Hindle 2004; Healey 2014). The most convincing ‘bottom line’ evidence of the Old Poor Law’s efficacy is the absence of a relationship between grain price rises and mortality spikes for the entire English population after 1623–24, indicating freedom from famine starvation two centuries earlier than most of the rest of Europe (Galloway 1988; Kelly and O’Grada 2011; Healey 2014, pp. 253–4).

This pioneering universal welfare system is of fundamental importance to the history of inequality. Firstly, it placed an effective floor of security under the lower end of the labour market. Secondly, it facilitated by far the highest rate of labour mobility seen in Europe c.1600–1834 (Wrigley 1967; Wrigley 2004, p. 89, Fig. 3.8). The younger generation could quit their parish of birth safe in the knowledge that it would always look after ill or elderly parents. Adam Smith got the mobility-promoting virtues of the Poor Law completely wrong (Campbell and Skinner 1976: 53–4). He seems to have been unaware of how much discretion poor law authorities were permitted in England, flexibly moderating their local policies to the patterns of labour demand in their own and other nearby parishes, as historians have now shown us (Taylor 1989; Wells 1993; Sokoll 2001).

It is, therefore, also possible to argue that the unusual, high-wage economy, which Allen has identified as being so propitious for early modern England’s precocious move toward labour-saving technology, is in part a product of the highly unusual institutional support for labour and its mobility and for the market price of grains provided by the Poor Laws.

By the same token, the radical overhaul of the Poor Laws that occurred in 1834, both turning them into a deliberately deterrent system and dramatically slashing in half (from over 2.5% of GNP to 1.2%) the value of transfer payments to the poor, was contributory to a quite severe increase in the precarity of any family whose breadwinning capacities might be impaired even just for a short period (Lindert 1998: 113–15). In a parliament mainly representing the landowning and gentry class, unhappiness with the strongly rising costs of the Poor Law since the 1760s had been steadily growing. So, when a Royal Commission led by representatives of the new ‘sciences’ of political economy and utilitarianism investigated and found (in a report that subsequently drew unanimous condemnation from historians for its blatant bases) that payments to people in their homes would only encourage further laziness, parliament acted decisively (Brundage 1978; Mandler 1987). Thus, the working classes were intentionally put into a state of chronic vulnerability to ensure they accepted the wage rates it suited employers to offer in the ‘free market’. The hated incarceral workhouses of the New Poor Laws—husbands, wives and sometimes children were segregated on entry—triggered widespread protests. The grievances fed into the decades-long struggle for the vote by working men, which began with Chartism, 1838–58 (Chase 2007). Membership of Friendly and Burial Societies to mutually self-insure against hardships and the usage of pawnshops for credit all multiplied as the working classes attempted to defend their families’ security in a free-market economy of withdrawn state support (Johnson 1985; Neave 1996).

By 1900, there had been 80 years of gradually rising average real wages. This was principally a consequence of reductions in the cost of living, particularly the basics. The cheap loaf was considered such a prized symbol of how free trade (symbolized in the Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846) had benefited the common people that defending it against the protectionist tariff reform movement won the Liberals a landslide victory from a predominantly working-class electorate in 1906 (Trentmann 2008, part I). However, despite the public health improvements since the 1870s in the sanitary environment and in infectious disease control, which meant that children aged 1 to 5 years no longer died in droves as they had in the 1840s (Mooney 2015), infants still did die at a ferocious rate (150 infant deaths per 1000 live births nationally). It has to be realized that the graph of rising average real wages applies only to a semi-fictional figure created by Victorian and subsequent statisticians: the full-time labourer blessed with less than average marital fertility, in rude health and continuous employment from age 12 years until—mercifully—dying in harness, rather than in the workhouse, at age 70 years. Furthermore, where inequality is concerned it has to be recalled this was also 80 years of runaway gains for employers, financiers and urban landlords, creating a peak in income and wealth inequality in the Edwardian period.

The fact that a life of precarious income insecurity was still the case for a majority of labouring families in 1900 was demonstrated by Seebohm Rowntree’s innovative investigations, which first brought to the attention of social policymakers the phenomenon of ‘life-cycle poverty’, causing an important change in policymakers’ understanding of inequality (Rowntree 1901). Rowntree showed that in a society lacking the kind of much-valued universal social security system that had existed before 1834, and which had been legislated since the 1880s in Germany, a normal working-class family—even with its main adult male breadwinner in employment and earning—would nevertheless experience absolute poverty at the point when they had several young children to feed, clothe and house. Additional misfortunes, such as illness or accident to the breadwinner, medical expenses incurred due to frequent childhood illnesses or temporary unemployment, could also tip them into absolute poverty.

Rowntree’s estimate was that 30% of the urban working class were living in poverty at any point in time, but this meant, as he emphasized, that a much greater proportion—probably most of the labouring poor—passed through poverty at various points in their life cycle, most unfortunately including the period when their family was full of growing children. Only those with the best-paid, skilled, unionized jobs or with small families (a growing practice, but only among some sections of the working classes in 1900) could hope to minimize ‘normal’ poverty, which meant children went hungry.12 When this precarity was confirmed by official enquires held in 1903–4, the response of the ‘New Liberal’ government elected in 1906 was to launch a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws but meanwhile also to pass a range of extensive social measures, 1907–11. These began to offer protections to the poor, notably including: old age pensions, free school meals, school medical inspection and—most expensively—national insurance for working men against illness, accident and unemployment (Searle 1971).

Forty years later, the modern, universal welfare state of citizen entitlement to free social security, health care and a range of social services was instituted in the UK and in many of the more economically developed nations of the world (including, though to a more limited extent, even the United States).13 The previous four decades had witnessed two world wars, mass unemployment and the complete breakdown in the 1930s of the 100-year-old, gold standard–based global trading system, along with the emergence of a revolutionary new Keynesian theory of state planning for the economy, and the rise of fully democratic electorates. Alongside Keynesian commitment to full employment, the welfare state provided the basis for three post-war decades of declining income and wealth inequality and rising affluence for a large swathe not only of the middle class but also the working class, free again from the fear of hunger for the first time in 110 years; working-class memoirs from England in the 1930s (such as Woodruff 2002) attest clearly to experiences of food poverty before the arrival of Beveridge’s welfare state.

The new post–World War II UK democracy had succeeded by c.1975 in reducing its own official measure of child poverty to 15% of all children, while the Gini coefficient registered a substantial decline in both income and wealth inequality to among the lowest in the developed world.

However, during the subsequent Conservative governments of Mrs Thatcher, 1979–90, the Gini coefficient of income inequality shot up in just ten years to the highest in Europe and the proportion of children growing up in official poverty more than doubled to over 30% (Resolution Foundation 2018). Atkinson showed that this was due to government policies, which both massively increased unemployment rates and, having made millions unemployed, also cumulatively cut their benefits (Tomlinson 2020, p. 527). It was also due to a regime of dramatic tax cuts for the highest earners, repeated again by George Osborne in 2010; and on both occasions James Mirrlees’ optimal tax theory of 1971 was part of the justification (Offer and Söderberg 2016, p. 171). Yet this Nobel-prize winner’s formalist theory was fundamentally flawed by its own self-contradictory asymmetric assumptions, most pithily summarized by Offer and Söderberg (2016, p. 173): ‘Optimal taxation…put together hybrid theories which combined the bad faith of asymmetric information with the good faith implicitly assumed in equilibrium analysis. This cannot be justified.’ More recent research by Diamond and Saez (2011), Piketty et al. (2014) and Atkinson (2015, pp. 179–88), taking into account a number of relevant factors insufficiently considered by Mirrlees, find that optimal taxation is progressive, with top marginal rates of at least 65% and up to 83%—both to maximize revenue and to take into account such issues as ‘fairness’, which one might have thought would be an essential consideration in a full democracy.

In 2023, despite the continuing existence of its welfare state and its NHS, the UK has now attained the undesirable status of being one of the most unequal societies in western Europe. A substantial proportion of its more than 30% of children living in poverty are now fed by over 2000 volunteer foodbanks, a new form of dependent vulnerability and inequality that did not exist before the Conservative-dominated governments’ 13-year sustained policy of reduced tax for corporations and the wealthiest, combined with austerity for the poorer half of the population. A 4-year freeze on all working-age benefits from 2016, the 5-week waiting period, the 2-child limit and squeezed housing benefits severely impacted all claimants. Hence benefits were worth 10% less by 2020 for an average out-of-work household than they had been in 2011, cutting £1600 off their income in real terms. For those with children, average benefits were worth 12% less than in 2011. This is equivalent to a loss in income of £2900 a year for families who had little margin above subsistence already in 2011 (Bourquin et al. 2020).

Education Provisions

Apart from social security and health care, the other major aspect of what we understand today by a welfare state is the nature of the provision of education and training on offer to the rising generation. This is the second major set of institutions that has influenced the general trends and patterns of inequality in British society. Once again, it is Elizabeth I, in two Acts at either end of her reign, in 1559 and 1601, who was a formative influence on the history of educational provision in England and Wales and its relationship with long-term patterns of inequality.14

Elizabeth I’s 1559 Act stipulated that in addition to instruction in Latin, all secondary schooling (provided at that time by several hundred philanthropically funded grammar schools) was to teach exclusively and compulsorily the doctrines of the new Anglican Church. Secondly, her 1601 Charitable Uses Act aimed to stimulate further the practice of making bequests for schools for the poor, by giving statutory recognition to founding ‘schools of learning’ ‘for the benefit of the public’ as a proper charitable purpose. Parishes were not permitted by the parallel 1601 Poor Law to use the local poor rates for such educational purposes, though they could use them to pay for orphans and poor children to be taken on as apprentices.

Thus, these Acts laid down for centuries to come, firstly, an intimate relationship between the interests of the state religion, Anglican Protestantism, and the nation’s secondary schools (and indeed its two Universities, Oxford and Cambridge, the majority of whose graduates were still in the 1860s entering the Church). Secondly, the provision of formal educational facilities was considered best left entirely in the hands of civic society and private initiative. Thirdly, apprenticeship in merely useful trades, as distinct from imbibing Latin and protestant theology, was differentially associated with the provisions of the Poor Law, along with providing manual work and sustenance for the unemployed.

It is truly extraordinary how fateful these three principles of what we might call the ‘Elizabethan educational settlement’ have been in determining the inequality-reproducing structures of the educational and training system serving the population of England and Wales, as it has evolved over the ensuing four centuries. As a result of this inheritance, firstly the British state was entirely content to leave to civic associations of working men the organization and provision of all forms of practical training in manual skills. In France and Germany, the training offered by guilds was brought under state supervision by the early 19th century, which, over the long run has enhanced their status. In Britain, the London guilds, along with friendly societies and trade unions all remained independent of such detailed state interference in their recruitment and training practices, leaving them with a separatist, ‘working-class’ status (Reid 2004, chapter 1).15

Secondly, the British state, relative to France, Germany, Holland and the United States, remained very hesitant to get involved even in elementary education (to age 11 years), preferring to leave it in the hands of religious organizations. When finally and reluctantly in 1902 it gave 150 electorally accountable Local Education Authorities (LEAs) the powers to ensure a coherent education system in all parts of the country, within the elementary component it was careful to preserve the many diverse ‘faith schools’, established over the course of many decades by the Anglican, non-conformist, Catholic and Jewish congregations (today one-third of state primary schools continue to be faith schools, including new Muslim schools).16 So religious diversity of provision was retained even within the state-funded system.

Thirdly, the historically long-established practice of philanthropic private provision of secondary, grammar schools for the poor has taken on an entirely new and different lease of life in the course of the last two centuries. Its original purpose has been completely subverted and turned on its head. This is of fundamental importance in the reproduction of elite privileges in British society, which strongly influences the structure of inequality.

The 1601 Act envisaged that it was a proper charitable purpose to provide for what we would today call social mobility. The aim was to encourage emulation of established royal practice: endowment of grammar schools to offer opportunities for boys born into humble or deprived circumstances to rise in society through their scholastic aptitudes to become Anglican clerics, even bishops. This was precisely the purpose of Eton College founded in 1440 by Henry VI to house and freely educate 70 poor boys.

However, as the centuries passed, many of the charitable boards running such schools increasingly succumbed to the practice of supplementing their revenues with fees from upper- and middle-class paying students, whose parents increasingly valued the route it offered to a safe haven in the Church, especially for younger sons. Eventually, an almighty parliamentary row broke out as the corrupted state of so many of the nation’s centuries-old self-governing charities was embarrassingly revealed by a series of no less than 32 enquires mounted in the period 1818–37 by Lord Henry Brougham, the same Whig reformer who was Lord Chancellor when the Great Reform Act was passed in 1832. Ultimately, all charities were brought under the watchful eye of a new Charity Commission established 1853–5 (Lowe 2021).

Seeing the writing on the wall, the leading charitable schools, such as Eton, Harrow and Winchester, which had by now built up a lucrative clientele educating the sons of the nation’s Anglican elite, had by the 1850s rapidly reformed themselves, following the model of Thomas Arnold installed as headmaster of Rugby School in 1827. His formula was to hive-off the local poor boys into a separate school to fulfil the charitable criteria, while taking primarily upper-class paying boarders from age 13 years in the main school. The revised curriculum on offer aimed to inculcate ‘intense patriotism, steeped in religious feeling’ and ‘patriotic militarism’ (Lowe 2021, chapter 2). First-hand study of the classics in Latin and Greek combined with competitive team-building sports was emphasized to be the acme of training for this new imperial leadership class. The successful strategy of these reformed elite educational institutions was formally confirmed by the Clarendon Commission report in 1864, which ensured that a handful of the nation’s most prestigious public schools should retain their charitable status while also remaining independent from oversight by the new Charity Commission.

Between 1840 and 1886, 72 new male public schools were created on this model, mostly in the Home Counties to cater for the demand from the rapidly growing and prospering metropolitan upper and middle class to guarantee their sons’ access to the imperial elite being incubated in these reformed ‘public schools’ (Banks 1954, Appendix R). Then, as competition for admission rose, 400 new fee-paying ‘preparatory’ schools appeared between 1870 and 1900 for those aged 7 to 13 years (Banks 1954, p. 190). Thus, an entirely independent, private fee-paying educational system for the nation’s social and financial elite emerged from the historic ‘charitable’ tradition- but excluding most of society from access due to the costs involved.17 Today this has grown to 1300 ‘independent’ schools educating the children of the wealthiest in society (and indeed from around the globe) while also receiving state maintenance in the form of tax-relief, calculated to be worth £640 000 per year in the case of Eton (Green and Kynaston 2019, p. 208). They receive the additional state subsidy of free training for those of their teachers who were in part or wholly state-funded through their education degrees.

Back in 1864–8 the Taunton Commission of 1864–8 had set out very clearly the overall architecture of the nation’s education system envisaged by the mid-Victorian parliament, still dominated as it was by the traditional landed elite (Piketty 2020, p. 177). They were now routinely sending their sons (and increasingly daughters, too) to private boarding schools for entry into the imperial, gentlemanly class. The Commission was entirely candid that the education system’s purpose was simply to replicate ad infinitum the prevailing structure of economic and social inequality, since any individual’s education was to be determined by the income of their parents.

The Commission envisaged four ranked grades of schooling, as follows.

- ‘Classical Schools’: Latin and Greek; education to age 18–19; mostly boarding; fees £60–£120 per annum (which was equivalent to a skilled manual worker’s annual income and so only affordable by the aristocracy and the Home Counties financial and professional elites).

- Second Grade Secondary Schools: Latin only; more ‘modern’/vocational subjects such as modern history, natural science, modern languages (permitted since the Grammar Schools Act 1840); education to age 16; day attendance, only; fees £10–£50 p.a. (affordable by the more prosperous among the commercial and professional middle classes).

- Third Grade Secondary School: no Classics; ‘a clerk’s education’, namely a thorough knowledge of arithmetic and ‘ability to write a good letter’; education to age 14; cost no more than £4 p.a. (affordable by the lower middle class and the aspirational upper, respectable skilled working class).

- Elementary education to age 12: ‘the three Rs’ (‘reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic’); cost no more than £1 p.a. Schooling on the cheap for the working classes: pupil teachers, large classes, both sexes mixed together.

Of course, in an industrial society it was accepted that the great majority of the population were to be catered for in grade D—elementary schooling, only.

It is intriguing to see how this socially conservative four-layered cake was yet again reconfirmed almost 60 years later on the eve of the end of the British Empire in the next major reform of the nation’s education system, which finally provided secondary education for all. It was carefully managed by another scion of this public-school and Oxbridge ruling elite, the Conservative wartime Minister of Education, R. A. Butler (with two sons at Eton at the time), and was influenced by the quasi-eugenic thinking of the 1938 Spens and 1943 Norwood reports (Lowe 2021, chapter 6).

From 1944, there were to be four grades of secondary schools: public (i.e. private) schools, grammar schools, technical schools and ‘secondary modern’ schools. The latter were for those failing an ‘11-plus’ aptitude test of supposed ‘innate ability’. Because, as subsequent educational research soon showed, it was a test biased towards middle-class socialization, secondary modern schools were mostly filled by working-class children, just like Grade D elementary schools in 1868 (Simon 1953; McKibbin 1998, pp. 217–35). For the few who could pass the test, it was now possible for lowly-born working-class children to move upwards, perhaps as far as grammar schools because attendance at these schools was now free. But the uppermost layer, where Butler’s sons were to be found, was carefully preserved in 1944, as in 1868, as an exclusive zone with a hefty price tag on the entry ticket to keep out all but the very rich.

Today it costs on average at least £17 000 p.a. for each child educated in private schools (over £40 000 at Eton). Each pupil taught in fee-paying private schools has had the benefit of exactly three times as much funding and twice as many teachers as in the schools attended by the rest of the population.

If the Deaton Review is to address not just the pattern but the deeper causes of inequality in British society, then it needs to take fully into account the powerful role of these separatist institutions for the wealthy to perpetuate their privileges. Educating just 6.6% of the population, they reproduce the majority of the top 10% by income and wealth and their products occupy 50% or more of the senior positions in the Cabinet and the civil service, in journalism and the judiciary (Green and Kynaston 2019, p. 5, Fig. 2). An historical perspective would, thus, suggest that England’s tax-subsidized ‘public’ schools be considered as one of the strongest and most pervasive influences on the reproduction of inequality. This would be well- reflected in the Palma ratio but such a measure does not begin to capture the profound and tightening stranglehold on political power and highest status opportunities of all kinds, which a private school education buys, as documented by the Sutton Trust (Kirby 2016)—and as revealed by the extraordinarily narrowly recruited, public-school dominated Conservative cabinets of Cameron and Johnson.

Political Powers

There have been major historical transformations in the relative political powers of institutions representing the interests of land, capital and labour. In 1600, landowners were without doubt in the driving seat, from the greatest of all—the Crown and the Church—through the Dukes and hereditary peers sitting in the House of Lords, down to the landed gentry, a representative sample of whom comprised many of the ‘commoners’ sitting in the House of Commons. Although there was a religiously-provoked conflict over the relative powers of the Crown and the lower house of parliament, which culminated in the trauma of the English Civil War, this did not disturb the rule of the landed interest, if anything strengthening it. It led to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and to parliament asserting its supremacy by the 1689 Bill of Rights; and by choosing its own monarch—installing the staunchly protestant William of Orange. In the 18th-century property-holders increased their accumulation of rents and landholdings through their use of parliament to promote enclosures of parishes and many other instruments of local economic improvement, boosting the concentration of landed wealth of both gentry and nobility at the expense of customary tenants and smallholders.18 With its system of locally-elected constituency M.P.s, the Anglican landed interests were able to continue to rule the roost in both Houses of Parliament right through to 1832 and even beyond—through the House of Lords—until 1911, as we have seen.

The period from c.1700 onwards, however, also saw an inexorable rise to greater power of two somewhat distinct socio-economic classes. Firstly, with the formation of the Bank of England in 1694, a private corporation with statutory protections to manage the government’s national debt, a secure anchoring institution was created further encouraging the growth of a rising class of rentier-citizens and associated financial service professionals, already associated with the City of London, the East India Company and numerous other early financial and insurance companies.(O’Brien and Palma 2023) Secondly, the northern and midland commercial and industrial bourgeoisie, many of whom were non-conformists now increased in fortunes and powers. Parliamentary reforms in 1832–5 endowed industrial cities with their first MPs and with elected local governments with a uniform franchise for all minor property-holders, amounting to about one-fifth of adult males. The Corn Laws, pouring money into the pockets of landowners, were repealed in 1846; and the nation committed itself to the free markets and global free trade of the new ideology of classical liberal economics.19 Great profits were reaped from making and selling manufactures worldwide, using steam-powered factories and cheap wage labour, so that capital replaced land and rents as the most lucrative activity—especially once England’s landowners encountered global competition as cheap food supplies and industrial raw materials flowed into Britain, all secured by the overwhelming power of the Royal Navy.

However, in the longer run, landowners, industrialists, financiers and merchants came together to form a new composite elite. And, certainly, in the shorter term, they could all agree that the most dangerous liberal idea—democracy, which had resulted in the loss of the American colonies—should be put on hold. As a result, the rise of capitalism was accompanied also by the relentless rise of inequality throughout the entire period to the cataclysm of World War I.

Despite their rapidly expanding numbers, the institutions to represent and promote the interests of waged labourers took decades—amounting to well over a century—gradually and painfully to build national political effectiveness, resourcefully resisted all along the way by the incumbent powers of the new compromise between land and capital, which Cain and Hopkins have dubbed ‘gentlemanly capitalism’, and which was formed in the fusion of the new elite’s public schools (Cain and Hopkins 2016). The workers were not slow to mount their initial campaign against ‘wage slavery’ and for the vote. However, the post-1832 reformed parliament, still dominated by Anglican landowners, successfully turned a deaf ear to the Chartists’ series of petitions of 1841–8. This was despite the fact that the largest, with 5.7 million signatures, impressively represented 72% of the 7.9 million persons, both sexes combined, aged 15–60 in 1841.

Over the next two decades, and despite the passing of the world’s first Public Health Act in 1848, the health of the over-crowded urban working classes suffered greatly from the burden of infectious and sanitary diseases (Szreter 2005, ch.6). However, continuing to press for the vote led to important parliamentary concessions between 1867 and 1872, the net result of which was to so significantly increase the voting power of working-class men in most urban constituencies that their votes could now outnumber those of the rate-paying propertied classes (Aidt et al. 2010). The industrialist Joseph Chamberlain, backed by his ward-level non-conformist Liberal caucus was able to get out the proletarian vote, wresting control away from the long-incumbent ‘do-nothing’ ratepayers’ party in Birmingham (Hennock 1973).

As thrice-elected mayor, 1873–6, Chamberlain pioneered the novel debt-financing (on the security of the city’s rate-base) essential to the success of the movement known as ‘gas and water socialism’. With his popular mandate, he got the council to agree to jack-up the city’s debt to the colossal sum of £2.5 million in order to buy up the local gas company (authorized by the Westminster Parliament because it recognized the legitimacy in liberal economic theory of the natural monopoly argument). This then generated a massive stream of revenue for cleaning up the city. The formula was so successful that, responding to demand from many other cities, HM Treasury commenced sanctioning a wide range of loans for sanitary and public health purposes (Harris and Hinde 2019, Fig. 10). At last, life expectancy in Britain’s cities, having been stuck in the doldrums for half a century or more, began to climb during each of the next four decades from 1870 onwards (Szreter 2005, chapters 6 and 7). Thus, given that health and survival are the most basic of measures of inequality, it can be seen that politics and a cross-class alliance between leading and visionary employers and their workers was a more important driver—than economics and relative incomes—of trends in this ‘biological’ dimension of inequality in industrial Britain right across the period c.1815–1914.

The Chartist demand for manhood suffrage was not finally achieved until after the war to end all wars in 1918; and a voting democracy for both sexes only arrived in 1928. Those rights were won in a protracted series of concessions wrung principally by the pressure mounted by the trade-union movement, which initially included only a small minority of craft workers. The major period of trade-union expansion was 1910–20 when combined membership rose 10-fold to three million, including for the first time lower-paid and less secure workers in a wide range of industries (Reid 2004, p. 229). A consequence was that the fledgling Labour Party, only formed in 1900, emerged at the 1922 election, thanks to a divided Liberal Party, as the official opposition in parliament to the Conservative government.

However, many of the most important initial statutory measures to redress the most gross aspects of inequality, built up over the course of the previous century and a half, had already been extracted by the smaller group of early Labour MPs, as the junior partner supporting the ‘progressive’ Liberal administration of 1906–14 (Reid 2004, pp. 259–66). The Liberals were responding to revelations about the poor state of physical health of working-class recruits for the Boer War, Rowntree’s demonstration of the life-cycle poverty in which poor children grew up, the miserable lives of the aged poor in workhouses, and the still shocking levels of infant mortality in many industrial towns—also to the threat to their vote represented by trade-union sponsored MPs and the Labour Party.

Local authorities were permitted to offer free schools meals, new Trade Boards ensured minimum wages in the most exploited industries (full of female home-workers), while the Trade Disputes Act and Workmen’s Compensation Act also gave labour rights that employers had previously resisted. Labour demands for legitimacy of trade-union political funds and for salaries for MPs (so their working men could afford to take their seats) were both granted to their allies by the Liberals. (Reid 2004, pp. XX) Finally, there were the famous big ticket items of ‘Bismarckian’-style National Insurance for working men paid for by progressive taxation, which the House of Lords foolishly opposed and thereby handed to Lloyd George the pretext the Liberals had been seeking for decades to dramatically reduce the upper house’s statutory potency. After hanging on to power for the entire 19th century, the hereditary aristocracy of landowners sitting in the House of Lords finally lost their parliamentary veto, while also succumbing to the principle of a long overdue progressive taxation on their inflated incomes and estates (Piketty 2020, pp. 176–85).

However, the economically severe inter-war decades saw only modest overall gains for labour incomes and the opening up of a new regional disparity. While the London economy diversified into new consumer goods, there was much privation and suffering in the north and midlands (Laybourn 1990; Pollard 1992, chapters 2–4). These regions bore the brunt of the permanent disruption in the markets for the products of Britain’s staple industries, which had begun during World War I. Indeed, this was compounded by the policy decisions of the nation’s re-formed and reconfigured financial elite—the gentlemanly capitalists and imperialists who populated the City, HM Treasury and the Bank of England. It was their interests that were best served by insisting on returning to the Gold Standard in 1925, thereby making British manufactures more expensive and condemning the north and the midlands to short-time working and penury. As for the reduction of women’s formal political disabilities some further progress was fought for and achieved in the 1920s, though little change in their exclusion from the higher-paid professional, managerial and commercial occupations where the marriage bar continued. (Thane 2022).

As is well known, the major event in the inequality history of the UK, confirmed by the reversal of Gini coefficients of income and wealth, occurred in the trans-war period c.1910–79 (Piketty 2014). This trend began with the pre-1914 progressive taxation and New Liberal legislation. It was maintained due to the wartime levelling-up of unskilled wage rates and the demographic and financial costs to the nation’s wealth elites of World War I. After the difficult inter-war decades, the trend towards greater equality was consolidated and extended by the combination of the second round of financial extraction from elites to pay for the 1939–45 war, combined with the wide range of reforms put in place by the first majority Labour government—exactly 100 years after Chartists had petitioned for the working-class vote.

The legitimating, new Keynesian theory and the practical proof of the efficacy of planned and nationalized industries, which won the war against fascism, were also important in ensuring that the new democratic consensus prevailed.

This meant that government policies to reduce inequality, to boost the share of labour and wages, as against capital, profits, land and rents, were in force through these decades. The accompanying high marginal rates of both income and wealth taxation—in the region of 80–90%%—were even accepted by three successive Conservative governments, 1951–64.20 This post-war settlement continued for a generation until the political counter-revolution of 1979–97, re-asserting the primacy of the interests of capital, land and, especially, finance (Gamble 1988; Shaxson 2018). Progressive marginal tax rates were then rapidly reduced to 40%, while regressive indirect taxation was increased. New legislation curtailed union powers of protest during a period of mass unemployment and a dramatic and fatal defeat was inflicted in 1984 by the government on the strongest trade union—in the nationalized coal-mining industry. The immediate consequences of all this for income inequality can be tracked in the Gini coefficient rising from 0.25 to 0.34, showing a reversal in a single decade of most of the egalitarian gains made over the previous half-century or more.

This once-off marked steepening of the gradient of inequality in the UK between 1979 and 1990, when the income Gini shifted from a prevailing level of 0.25, 1961–79, to a new level ever since of between 0.34 and 0.36, has had a continuing effect of additionally increasing inequality further in the decades since 1990. This is despite the fact that the Gini value has hardly changed.21 The reason for this lies in the interaction with the growth of national income, which has fluctuated around an average of about 2% p.a.22 As each year passes, this seven-fold gap is also growing by about 2% more in absolute terms (due to the growth in national income), a compound interest rate that adds 81% additional widening in the inequality gap over 30 years. Thus, as a result of the combined effect of this, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows the Palma ratio for equivalized disposable income continuing to rise after c. 1990 and peaking in 2007–08 (then declining after the financial crash to 2016–17, before rising back somewhat already by 2019–20).23

It is instructive to consider how the wide range of political, lobbying, advertising and mass media communication resources deployed by the wealth elites in the 21st century have very effectively promoted their financial self-interests, in addition to the Conservative Party. This helps in explaining both the marked rise in inequality that has occurred in the UK and also its apparent public acceptance—sufficient to return Conservative governments since 2010 that have deployed aggressive inequality policies.

Here we enter the contentious area of the politics of knowledge and the importance of control over information communication. The American and French Revolutions had been sharp reminders that the ideas and views of the common people could be dangerous for the elites and this had informed the state’s preparedness—later relented—both to outlaw trade unions and to tax the free press. These repressive measures were also accompanied by some charitable attempts by evangelicals from the 1810s onwards to minimally educate the illiterate poor in elementary schools which taught Christian meekness and ‘knowing one’s place’. Much later, once the votes of ordinary working-class people came to acquire evident political importance after the franchise reform Acts of 1867, 1872 and 1884, there were renewed efforts to guide the people’s thinking along politically safe lines through the innovation of universal elementary education and mass-circulation daily newspapers owned by plutocrats. By the post-1945 era, with the rise of the Labour Party, there were well-established, competing mass-circulation papers appealing to both Labour voters and to Conservatives.

Added to this, however, there have emerged the patently anti-democratic practices of ‘dark money’ buying lobbying power and influence. A number of high profile organizations, such as the Adam Smith Institute and the Institute of Economic Affairs, though often designated by the neutral term ‘think tanks’, have been anonymously funded by wealth elites for decades, unlike genuinely democratic, transparently funded think tanks, which disclose their sources of financial support.24 The convening of meetings and lavish dinners with ministers and activating ‘back-door’ contacts for contracts among individuals known to politicians was an abuse repeatedly exposed to view during the COVID era.25 There has also been the attempt by government ministers to determine the kind of official information published. A major example of this with direct relevance to the Deaton Review’s work is that on taking office in 2015 one of the Conservative government’s first acts, no longer shackled by their coalition with the Liberals, was to repeal the 2010 Child Poverty Act, which had set statutory targets for the reduction of child poverty, requiring future governments to make sure policies were in place to achieve this. While preparing to remove the Act from the statute books in 2016 the Conservatives had also planned to stop publishing official data that would enable trends in child poverty to be tracked. They only backed down on this in the face of highly vocal protesting campaign groups, charities and academic social scientists (see Cooper and Szreter, 2021, pp. 214–15) of a true storm of public protest.26

The interaction of all these factors together can form a potent cocktail, which, without being blatant and self-evident ‘fake news’, can extraordinarily skew what politicians (and journalists, too) think public opinion is—when it may not be. A crucially important example of a case in point—relevant to the whole recent and future history of inequality—is the public discourse during the last several decades on taxation. It was accepted as a shibboleth of the election-winning governments by New Labour throughout their administration, 1997–2010, that the Conservative era of dominance, 1979–97, had established that ‘the public’ simply would not brook income tax rises. The Labour government’s room for manoeuvre was therefore to some extent constrained. In order to attempt to improve the infrastructure for delivering public services, neglected by 17 years of Conservative underfunding, they adopted the strategy of using the infamous PFI deals. These were finally abandoned by Conservative Chancellor Hammond in 2018 for the very good reason that they required an extortionate payment model because the private sector is not suited to fund long-term public investments of this kind, as explained by Offer (2022). The consequence of all this is that we remain in the UK in 2023 with high rates of regressive indirect taxes and an absence of all but the most mild form of progressive taxation, completely unlike the rates reaching up to 80–90% on top incomes and wealth, seen in Britain’s era of greatest productivity growth and greatest social equality, c.1950–73.

However, reputable independent survey information, the British Social Attitudes survey (BSA), has been published annually throughout the period since 1983, which has always shown consistently that only a small minority of the public, barely above 5%, were positively in favour of lower taxation if it meant a reduction in public services, while in most years an absolute majority (50% or over) were in favour of higher taxes (the balance being for no change).27 Nevertheless, journalists and New Labour politicians alike all believed the public had turned decisively against income taxes as being too onerous and that this had happened during the 1970s –and was one of the reasons Mrs Thatcher was elected and why her project remained an electoral success. This is also a view that can be found in recent scholarly histories of taxation (Whiting 2000; Daunton 2002).

New doctoral research has established that no such evidence can be adduced for the period before the BAS began in 1983 and nor can any focus on this issue be found before the mid-1980s in the archival papers of the two main political parties, or the TUC, or the CBI.28 From the late 1940s through to 1979, inclusive, it is in fact only in occasional articles in the national press that assertions (with no evidence) can be found about the British public’s lack of appetite for taxation; and this only becomes relatively pronounced (in the press) at the time of the 1987 election and is again repeated by the media in the run-up to the 1992 (tax bombshell) election. Furthermore, the notion that British public attitudes themselves turned negative toward taxation during the 1970s is an entirely post-hoc invention, with no contemporary evidence from the 1970s to support it. The portrayal of public attitudes to tax rises in the national press was predominantly negative across the political spectrum from 1987 onwards and Labour front-bench politicians were never willing to challenge this—even though the BAS and other surveys of public opinion offered little evidential support for it!

Of course, income tax rises would have significantly impacted on the personal earnings of national newspaper journalists, members of parliament and everybody else on mostly middle-class salaries in the Westminster political world. John Cole, probably the most acute and celebrated political journalist the BBC has ever employed, candidly pointed this out, as also did the Labour front bench themselves in the run-up to the 1992 election. Indeed, Cole outright accused his colleagues in the press of bias in reporting on tax-raising policies:

‘… governments of the left which wish to use taxation as a means of redistribution and to fund improved public services have to argue their case and risk displeasure. The fact that this displeasure comes from the better-paid and often more articulate sections of the community, adds to the risks. When John Smith mentioned that he, Neil Kinnock, Jack Cunningham and other shadow ministers at Labour’s news conference would be among the “losers” under his [tax] proposal, the point was made. A high proportion not only of editors, but columnists, headline-writers, and lesser breeds below the newspaper fold fall into the same financial category. So these are proposals, which in the race for a good press, start some way behind the starting line.’29

As the Sutton Trust has recently shown, it is also the case that 50% of editors of leading publications and as much as 44% of media columnists are drawn from the 6.6% of the school population who attended expensive private schools, a small but influential constituency not known for their appreciation of progressive taxation. It seems plausible to suggest that it could be, at best, their unconscious bias and, at worst, simply their self-interested perspective that explains the consistent discrepancy between media presentation of the nation’s attitudes to taxation and the actual attitudes of the 93.4% who are not paying private school fees.30

Policy Conclusions from History in the Post-Pandemic Era

Seven contemporary policy conclusions can be drawn from this historical commentary.

Firstly, history shows that inequality is highly variable. The degree of inequality that has existed in Britain over just the last 120 years has included the record-breaking excesses of the imperial metropole in the first decade of the 20th century followed by a trend towards the most egalitarian period in Britain’s recorded history, c.1945–80, succeeded once again by an era of rising inequality to 2023.

Secondly, history attests that all the institutional forces examined here are resources that can be mobilized either for or against the promotion of equality. This is no surprise in relation to ideas and observational measures, ideologies and politics. But it is perhaps a little less obvious without an historical exposition in relation to the nation’s education system and its welfare provisions. These can be viewed in a somewhat naïve way as institutions that must, by definition, promote the nation’s human capital and assist the vulnerable. Indeed, they do—but not necessarily equally so. History shows that while the original intentions of founding grammar schools in the medieval and early modern period may have been genuinely philanthropic, encouraging what we would today call social mobility, throughout the last two centuries the wealth elites and their representatives in government have repeatedly taken great care to ensure that the nation’s changing structure of educational provision continues to ensure their privileged intergenerational access to high-status jobs, income and wealth.

Similarly, though Britain has had a universal welfare system since 1601, during two periods, 1834–1945 and 1979–2023 (with an all too brief respite c.1997–2010 as shown by Joyce and Sibieta 2013), it was re-designed in such a way as to stigmatize those needing to draw support from it. The net effect in both periods was to segregate, ingrain, deepen and intensify the experience of poverty for those unfortunate enough to need the collective resources begrudgingly provided to keep them alive.

This is highly relevant in the current context. Sir Michael Marmot, the champion of the globally adopted approach that addresses ‘the Social Determinants of Health’, observed, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, that the tightening of the screws under the decade-long austerity regime has meant that the decadal increase in life expectancy—which has been a sustained demographic feature for over a century—had slowed down right across the nation (Marmot et al. 2020a, p.15, Fig. 2.2). Indeed, for much of the decade (2010–12 to 2016–18) female life expectancy had even gone into temporary decline in the 10% of most deprived districts (Marmot et al. 2020a, p. 18, Fig. 2.5). Marked and widening inequalities in health and mortality were at their greatest across the whole decade between the most deprived neighbourhoods of the north-east and the most privileged neighbourhoods of London. These are among the most poignant and fundamental of all the myriad manifestations of inequalities; and they are the hardest to find any justification or rationalization for in a liberal democracy, not lacking in resources.

Thus, Richard Horton has argued that in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic Britain had among the highest excess death rates in western Europe because a deliberate government pro-inequality policy since 2010, involving a run-down of the welfare state and the NHS, had turned the COVID-19 infection into a ‘syndemic’ (Horton 2020). This is the coming together of the novel deadly respiratory illness, COVID-19, with a range of non-communicable health conditions (diabetes, obesity, etc.), which are already embedded by social inequality. A syndemic occurs when these risk factors intertwine and reinforce each other to exacerbate the lethal burden of disease, having its greatest effects on the poorer half of the population, which includes many of those working in exposed front-line public services, providing essential health care, social care or transport services; this has also interacted with the higher likelihood of ethnic minorities working in these lower-paid occupations (Singer 2009). This has also been empirically confirmed in Marmot’s first major post-COVID-19 report issued on 15 December 2020 (Marmot et al. 2020b). The difference between the death rate due ‘merely’ to pandemic COVID-19, as against the magnified effect created by a syndemic, can be robustly, if approximately, quantified by the fourfold greater death rate per million from COVID-19 in the UK at that time, compared with Germany, a population of comparable size, age and ethnic diversity, in which its welfare, health-care systems and poorer citizens were not subjected to a decade-long stigmatizing austerity policy in response to the financial crisis of 2008.31

Thirdly, history teaches that ideas and language are extremely important. ‘Pauper’ was turned into a hateful de-humanizing term when used by the Victorians. The depiction of poverty as a shameful condition should be accorded the status of hate speech. Discriminatory and disrespectful language towards the poor should be treated the same way as prejudices towards all other forms of intersectional inequality: age, sexual identity, gender, disability, skin colour, ethnicity. This must include ministers or MPs talking of shirkers or using other disrespectful forms of language of their fellow citizens.

Fourthly, to do anything about the social causes of inequality, the child-poverty rate should be promoted to equivalent importance in our public discourse to that currently enjoyed by GDP. Clear targets should be set for at least 2 percentage-point reductions each year for the next 15 years, with a final target of 0% growing up in poverty. If that seems over-ambitious, remember that Labour pledged in 1997 to end child poverty within a generation and don’t forget that under Mrs Thatcher’s administration, her policies produced close to a 2-percentage point increase in child poverty each year she was in office.32

Fifthly, as to the nation’s public schools, there can be no justification for charitable status for businesses charging up to £40 000 p.a. to the world’s wealth elites to ensure their children’s access to high-paying careers and marriage partners. Initiatives to create bursaries to admit poor scholars only emphasize the fundamental injustice of the whole system. To take this approach to its logical conclusion, supposing every private school was to make every one of its places available to a random lottery of 6.6% of children drawn from all the nation, so this lucky few could each receive three times the educational resources of everybody else. Would that be a fair system? Fairness can only truly enter the system when class sizes, pupil–teacher ratios and funding per pupil in private, ‘independent’ schools and in state-maintained schools are equalized. A cost-free start in the direction of fairness would be strict quotas in Russell Group universities to ensure that the offer and take-up of places to students from each sector is proportionate (ie 93.4% for state school pupils). This would constitute formal recognition of the need appropriately to allow for the gross discrepancies in resources if the university selection system is count as genuinely meritocratic.

Sixthly, the bargaining power between labour and capital, and between employees and employers needs to be re-balanced. Since John Stuart Mill’s 1862 edition of his textbook, Principles of Political Economy, it has been recognized that there is no good reason, in terms of competitive free market economics, for employers and capitalists not to be subject to the discipline of collective bargaining over employees’ remuneration and conditions of employment (Biagini 1987). Without sufficient trade union strength we have the ridiculous travesty, powerfully depicted in Ken Loach’s 2019 film, ‘Sorry We Missed You’, of the increasing in-work poverty and precarity of the casualized gig economy. This means that, in the supposed name of free market economics, taxpayers are topping up the incomes of underpaid workers so that inefficient employers can conduct a low-wage operation and still make a profit without bothering to invest or manage in such a way that takes into account their workers’ lives as family members. The low-wage economy that results from the lack of labour bargaining power may well be partly driving the much-discussed ‘productivity puzzle’ of the last decade.

Finally, history shows that the social security, welfare and health system, which empowers all citizens to flourish, develop their talents and access opportunities on a more genuinely equal—and therefore more truly meritocratic—basis, needs to be fully funded so that it can truly deliver Michael Marmot’s important principle of non-stigmatizing ‘proportionate universalism’ (those who start with the least in life get compensatingly more and better support). (Marmot et al. 2020a). This requires progressive taxation of income, wealth and inheritance, similarly to the way it was applied during Britain’s most successful period of post-war economic growth, c. 1950–1973. Additionally, it is extremely important to take into account in favour of this policy, as Thomas Piketty has cogently argued, that progressive taxation is not principally about the amounts of money raised from the wealthiest citizens. It is in order to achieve consent among all the middling ranks of income earners beneath the uppermost elite to the fairness of the principle of paying a rising proportion of their incomes in tax. If we all know that all those better off than ourselves are paying proportionately more of their additional resources, the tax system can itself be seen as fair and as symbolizing a collective form of justice and proportional universalism (Piketty 2020, p. 462).

This is what it means to be part of a democratic society offering fairness and empowerment to all of its citizens.33 There would still be plenty of room for a range of richer and poorer, but it means that, over time, individuals with literally 100—or even 1000 times—as much income or wealth as the average of others will cease to exist. No great loss for a true democracy of political and civic equals. There are other things to do in life than amass private fortunes on that scale—such as to take pride in contributing to the sustainable welfare of one’s fellow and future citizens, as has characterized British culture during long and economically successful periods in our past.

Appendix

Endnotes

- See Joyce and Xu (2019).