The English already had developed a model of policing Ireland and their other colonies.

Police accountability is an issue that has been with democracies since modern police were created. Citizens should be concerned about controlling police: they have immense authority; they are armed and authorized to use force; and unlike the military, they are not sequestered on bases—they are spread throughout the community.

Modern American policing had its origins in England, where, in 1829, the questions of whether to create a police force and, if created, how to keep this force accountable were debated by political, social, and philosophical elites for more than a century. Everything about policing was―on the table in this debate—the relationship of police to political authority, activities that would constitute the business of policing, organizational structure and administrative processes, and the means by which police would obtain their goals.

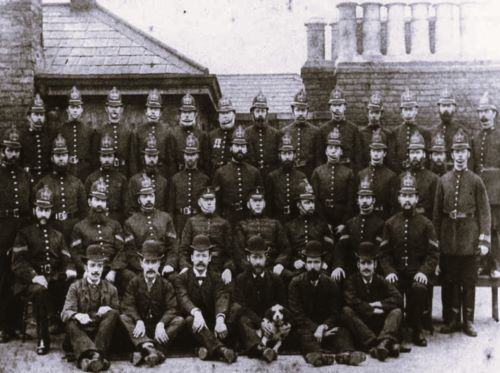

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the English stared across the channel at the French, or continental, model of policing, which relied upon secret police and paid informers. Likewise, the English already had developed a model of policing Ireland and their other colonies with armed mounted police operating in groups bivouacked to avoid contact with the native population.1

The English decided neither of these models was acceptable. Early English policing emphasized uniformed, unarmed, highly recognizable officers who were diffused geographically throughout London and patrolled on foot. These officers not only were granted authority from the Crown but also had to earn the citizens‘ trust. Investigations conducted by plainclothes police, at least initially, were rejected; victims pursued criminal investigations through some form of stipendiary police. Unobtrusive policing by public investigators risked police meddling in political matters, and militarized policing risked further alienation of the general population. The primary business of police was to prevent crime through presence, persuasion, and reduced opportunities.

In the United States, cities adopted the English model of policing. Although not originally outfitted in uniforms—this was deemed European elitism—American police were similarly diffused throughout cities, like their English counterparts, to prevent crime. For American police, the issue of who would control the police—urban political bosses or descendants of the original Dutch and English settlers—was the dominant public concern. This struggle to control police forces was to shape American police in remarkable ways.

During the first stage of evolutionary development (roughly from the 1850s to the 1920s), police were largely under the control of urban political machines; during the second stage (roughly the 1930s to the 1970s), police, with the support of the progressives, evolved into virtually autonomous urban agencies. Herman Goldstein has described police as evolving into the least accountable branch of urban government during this era.2

To achieve this shift—from politically dominated and controlled to virtually autonomous forces—practically every aspect of American policing was reformed during the early decades of the 20th century. Leading police thinkers (like O.W. Wilson, Leonard Fuld, and Bruce Smith) were overwhelmingly preoccupied with issues of control—that is, both wresting control of police at all levels from political influences and ensuring that only ―professional‖ police influence police. Bruce Smith, for example, wrote in 1929: ―Without exceptions, all proposals for improvement of organization and control have necessarily been aimed at the weakening or the elimination of political influences.3

In the name of eliminating corrupt political influences from policing, these men attempted to change the nature of the business from crime prevention to reactive law enforcement. They restructured police organizations, revised administrative processes, developed new tactics, and redefined the relationship between police and citizens—each, more or less successfully—all with an eye toward gaining administrative control of police, whether field commanders, supervisors, or patrol officers.4

By the 1950s, theorists wrote about the conduct of police work—services line officers perform in the course of their daily work—as being semiautomatic (i.e., police responses to incidents could be, or should be, so controlled as to be analogous to typing, piano playing, or rote adherence to a script). O.W. Wilson wrote in 1956, for example:

Administration has been defined as the art of getting things done. Police objectives are achieved by policemen at the level of performance where the patrolman or detective deals face-to-face with the public—the complainants, suspects, and offenders—and the success of the department is judged by the performance of these officers.

Decisions that are advantageous to the department are most likely to be made by policemen who have been selected in a manner to assure superior ability, who understand the police objectives and are sympathetic to them, who are loyal to their department and capable of operating effectively, efficiently, and semiautomatically (i.e., with a minimum of conscious self-direction, as in performance by a skilled typist or pianist), and who have high morale (i.e., the condition described by military leaders as the right heart). (Emphasis added.)5

Police work, in this view, as Egon Bittner once said, could be conducted by persons who have―the ‘manly virtues‘ of honesty, loyalty, aggressiveness, and visceral courage.6 The idea of officers thinking before they acted was to be discouraged. They were to follow rules loyally. The perception of police work as simple and under administrative control was shattered, of course, by research conducted in the 1950s by the American Bar Foundation, which showed that police work is complex, that police use enormous discretion, that discretion is at the core of police functioning, and that police use criminal law to sort out myriad problems. The research suggested that the control mechanisms that pervaded police organizations—especially rules and regulations, oversight, and militaristic structure and training—were incompatible with the problems that confront police officers daily and the realities of how police services are delivered. Aside from several who were scholars, few police administrators realized how ―out of touch existing practices were with day-to-day police realities. Paradoxically, a policing strategy that was overwhelmingly preoccupied with control, in the final analysis, failed to meet its most essential criteria. True, the strategy largely eliminated corrupt political influences in police departments.

However, it left officers mostly to their own devices in conducting the bulk of their work. This state of affairs has not gone unnoticed in either the legal or research community. The U.S. Supreme Court, for example, grew impatient with the unwillingness or inability of police executives to control criminal investigations—it was widely acknowledged since the 1930s Wickersham Commission that police procedure embraced the practice of torture—and through a series of decisions during the 1960s (the exclusionary rule, the requirement that offenders understand their right to an attorney, and so forth), established guidelines that shaped the future conduct of criminal investigations.7 Egon Bittner, based on his own research of police handling of drunkenness and mental illness, has written both eloquently and indignantly about the mismatch between ―official and real police work:

The official definition of the police mandate is that of a law enforcement agency. . . . The internal organization and division of labor within departments reflect categories of crime control. Recognition for meritorious performance is given for feats of valor and ingenuity in crime fighting. But the day-to-day work of most officers has very little to do with all of this. These officers are engaged in what is now commonly called peacekeeping and order maintenance, activities in which arrests are extremely rare. Those arrests that do occur are for the most part peacekeeping expedients rather than measures of law enforcement of the sort employed against thieves, rapists, or perpetrators of other major crimes.

For the rich variety of services of every kind, involving all sorts of emergencies, abatements of nuisances, dispute settlements, and an almost infinite range of repairs on the flow of life in modern society, the police neither receive nor claim credit. Nor is there any recognition of the fact that many of these human and social problems are quite complex, serious, and important, and that dealing with them requires skill, prudence, judgment, and knowledge.8

Endnotes

- Tobias, John J., ―The British Colonial Police: An Alternative Police Style, in Pioneers in

Policing, ed. Philip John Stead, Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1977: 241–261. - Goldstein, Herman, ―Categorizing and Structuring Discretion, Policing a Free Society,

Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company, 1977: 93–130. - Smith, Bruce, ―Municipal Police Administration, The Annals 146 (November 1929): 27.

- Kelling, George L., and Mark H. Moore, ―The Evolving Strategy of Policing, in Perspectives

on Policing, No. 4, Cambridge, MA: U.S. Department of Justice and Program in Criminal

Justice Policy and Management, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard

University, November 1988. - Wilson, O.W., ―Basic Police Policies, The Police Chief (November 1956): 28–29.

- Bittner, Egon, Aspects of Police Work, Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990: 6–7.

- The Wickersham Commission was the first national survey of criminal justice and police

practices. - Bittner, Aspects of Police Work.

Originally published by the National Institute of Justice, October 1999, to the public domain.