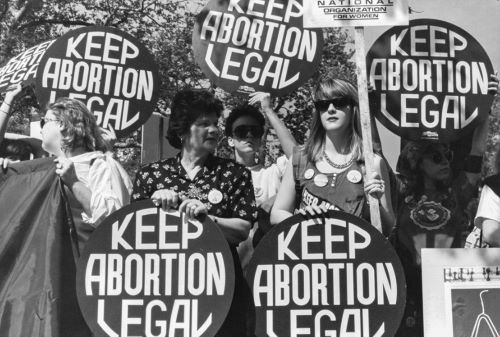

In recent debates over abortion laws, history has been front and center.

What Women Chose

Safer Than Childbirth

Abortion in the 19th century was widely accepted as a means of avoiding the risks of pregnancy.

At our rural county’s historical society, the past lives loosely in bulletins, news clippings, plat books, and handwritten index cards. It’s pieced together by pale, gray-haired women who sit at oak tables and pore over old photos. Western sun filters in, half-lighting the women as they name who’s pictured, who has passed on. Other volunteers gossip and cut obituaries from local newspapers.

I was sent here by hearsay. For years, my neighbor has claimed that the old cemetery in the low-lying field on my Wisconsin property contains more bodies than the scant number of tombstones indicates. The epic flood of 1978 washed away the markers of the nameless—Civil War soldiers, he says. I want to know who the dead were in life. After many walks through the cemetery, I’m familiar with the markers that remain. One narrow footstone reads simply, “MAS.” Three marble headstones rest at odd angles among the box elder trees. Stained, eroded, and lichen crusted, the stones belong to a boy and two baby girls who died in the 1850s and ’60s. On the boy’s is a relief of a weeping willow; on the sisters’ are rosebuds. Signs of young lives cut short.

I’m sitting at one of the oak tables when Carol, the historical society’s assistant curator, hands me a binder of cemetery records. A stranger has just sat beside me, her husband opposite us. I study the list of those buried on my land. I recognize the children’s names. I don’t see any men’s names. But there’s the name of a woman I’ve never heard of. I read it aloud: “Nancy Ann Harris.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE AMERICAN SCHOLAR

Aborted Fetus and Pill Bottle in 19th-Century Outhouse Reveal History of Family Planning

Two 19th century outhouses provide rare archaeological evidence of abortion.

The archaeological discovery of presumably aborted fetuses in outhouses in New York along with pill bottles and historical records have led researchers to conclude that many 19th century American women had family-planning concerns similar to those of 21st century women.

Writing in this month’s Historical Archaeology journal, archaeologist Andrea Zlotucha Kozub of the Public Archaeology Facility at Binghamton University details her discovery of fetal remains and associated artifacts in two upstate New York domestic outhouses. Although potential aborted fetuses have been previously found in an outhouse associated with a 19th century brothel in Manhattan, Zlotucha Kozub’s study is the first to find this sort of evidence from middle-class houses.

“Ladies of the night may have had the recurring need for abortion,”Zlotucha Kozub writes, “but historical documents show that housewives, particularly those from the White, Protestant middle class, regularly used abortion as a form of contraception.” However, she notes that defining abortion in the 19th century is made difficult by the fact that the word was used to describe both naturally occurring and induced miscarriages.

My Grandmother’s Desperate Choice

My questions about my grandmother’s death – from a self-induced abortion – haven’t changed since I was 12.

As a child, I knew only that my grandmother had died when my mom was still a baby. The one time I asked what had happened to her, a bolt of panic flashed across my mother’s face. “A household accident,” was all she said.

I was twelve years old when she finally told me the truth. Some friends and I had got into a long after-school discussion about abortion, prompted by the gruesome posters that a protester had staked in front of the Planned Parenthood in our Vermont town. I had already begun reading my mother’s Ms. magazines cover to cover, but this was the first time I’d encountered a pro-life position. When I hopped into my mom’s car after school, I was buzzing with new ideas. I had almost finished repeating one friend’s pro-life argument when I saw the look on Mom’s face. That’s when she told me: the “household accident” that had killed her mother had, in fact, been a self-induced abortion.

Her hands were tight on the steering wheel as she spoke. I realized later that it wasn’t the topic of abortion itself that made her so uneasy—she was a nurse and a Roe-era feminist who usually responded straightforwardly to even the most embarrassing health questions. Rather, her anguish arose from sharing a truth that she’d been brought up believing was too terrible to speak.

Sitting beside her in the passenger seat, I struggled to absorb the meaning of what she’d told me. I had only just grasped what abortion was a few hours earlier, and was still trying on this new pro-life idea. “O.K.,” I said, “but what about the uncle or aunt I never had?” Mom whipped toward me, face taut with a rage and fear that I somehow understood had nothing to do with me. “What about the mother I never had?” she said.

Until recently, everything my mom knew about her mother fit into one three-ring binder. Inside were letters, documents, and photos that my mother had collected over the years. After the election last fall, as an Administration hostile to women’s reproductive rights settled into the White House, I asked her to send the binder to me, and did some sleuthing of my own. I got in touch with aging relatives and family friends, who offered crumbling bundles of my grandmother’s letters, carefully preserved for decades. My questions about her life and death hadn’t changed since I was twelve years old. What felt new, in the Trump era, was the urgency of her story.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORKER

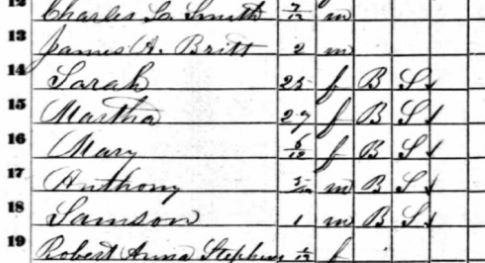

Sarah

An 1860 census record offers a glimpse into the choices available to pregnant women who were enslaved.

The known facts about Sarah’s life begin with one handwritten line in the 1860 U.S. Census. Even this brief individualization represented an anomaly. More than 99 percent of African Americans in Sumter County, Georgia, appeared without names in this simple government spreadsheet that apportioned power in the form of congressional representatives and electoral votes. Sarah was one of only 48 African Americans in the county named in this document by the local farmer and slaveowner who served as the census enumerator that year.

Sarah’s name harkened back to the wife of Abraham in the Book of Genesis and the start of important genealogies for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Born in Georgia about 1835, Sarah may have worked in a house or a kitchen or the cotton fields. The census worker listed her as unmarried; however, this marital status reveals little about her personal life because Georgia did not recognize enslaved unions. Sarah was pregnant though at the beginning of 1860. While the exact circumstances of her pregnancy went unrecorded, it can be inferred that Sarah did not want to bring a child — or perhaps an additional child if she was already a mother — into this world.

Sarah lived in southwest Georgia, a remote place with important links to broader histories. In 1864 and 1865, it became infamous for “Camp Sumter,” more commonly known as Andersonville, where 13,000 U.S. soldiers perished for want of shelter, wholesome food, and clean water. In the twentieth century, an interracial Christian commune launched a partnership housing program that became Habitat for Humanity. Jimmy Carter, born in Sumter County, became the first president born in a hospital and the first president from the deep South since before the Civil War. In 1860, though, Sumter County exemplified the “Black Belt” or what W.E.B. Du Bois later called “the shadow of a dream of slave empire” as he narrated his passage through the region. Slavery was more common than freedom here. The county’s enslaved population grew from 29 percent of the total population in 1840 to 52 percent in 1860. The 1840s and 1850s also saw an increase in large plantations. John B. Lamar, the brother-in-law of Howell Cobb who had large plantations across the state, kept 193 enslaved people in Sumter County alone on the eve of the Civil War.

Sarah had few choices and these options reflected an important day-to-day fault line under slavery. Slaveowners wanted enslaved women to produce children. Historian Sharla Fett writes that “soundness,” from the perspective of slaveowners, meant “an enslaved person’s overall state of health and, by extension, his or her worth in the marketplace.” Soundness equated to strength, a clean medical history, a good outward disposition, and for women it included the likelihood of having children. In January 1850, an overseer on John B. Lamar’s plantation in eastern Sumter County, settled his account with Polly Taylor, a local midwife. He paid her $16.50 “for midwife services to Antoinette, Harriet, Marry Ann, Viniy, Nancy Florida, and Fanny.”

Yet try as they might, slaveholders could never turn human beings into the extensions of their will. Contraception and abortion were methods of asserting control over one’s own body even if that body was legally owned by someone else. It could also mean resisting the dehumanization of slavery, including the threat of sexual violence posed by owners and overseers.

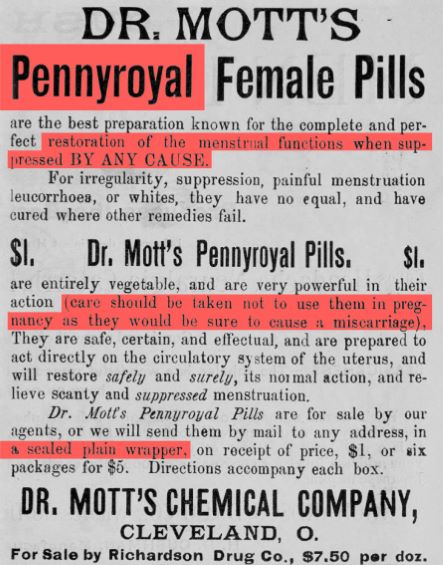

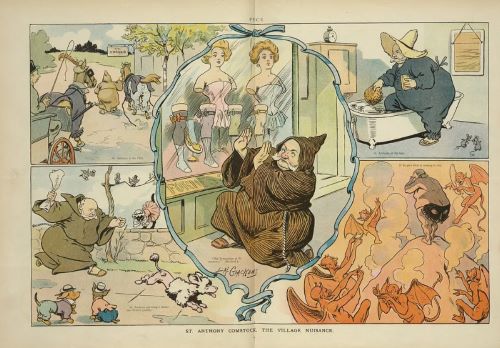

Contraception and abortion became more visible in nineteenth-century America until the Comstock Law of 1873 forbade “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material in the mail and more and more state legislatures criminalized abortion. Yet before the Comstock Law, physicians specializing in abortions and merchants specializing in abortifacient pills made the practice readily available for women with money. By one estimate, and the trustworthiness of these estimates are debatable, there was one abortion for every five or six live births by the 1840s and 1850s.

The patent medicines advertised in newspapers to produce abortions would have been difficult for Sarah to procure. She and other women relied on medicine practiced by enslaved midwives, root doctors, and herbalists. Enslaved women used cotton root on plantations before apothecaries began selling it as an abortifacient. In 1860, southern white physicians discussed herbal ways that enslaved women were believed to end pregnancies. The plants included tansy and rue as well as the “roots and seeds of the cotton plant, pennyroyal, cedar berries, and camphor.”

Patterns of miscarriages caught the attention of slaveowners. In 1855, rumors abounded in eastern Sumter County that the cruelty of overseer Stancil Barwick had resulted in enslaved women losing pregnancies in the field. When John B. Lamar asked his overseer for an explanation, Barwick described two recent miscarriages. A woman named Treaty lost a child, but Barwick said he knew nothing about it. He admitted that Louisine, about five-months pregnant, worked in the cotton fields that July, but he asserted “she was workt as she please[d].” In Barwick’s telling, Louisine came to him and told him she was sick. “I told her to go home,” he said. “She started an[d] on the way she miscarried.” Barwick believed enslaved men had spread these rumors to injure his reputation. He gave no outward indication the women intentionally ended their pregnancies, and the ambiguity of miscarriage provided cover for individual decision making.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE JOURNAL OF THE CIVIL WAR ERA

Coat Hangers and Knitting Needles

A brief history of self-induced abortion.

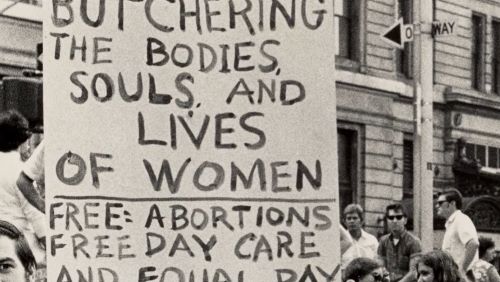

Knitting needles. Arsenic. Deliberately falling. These are just some of the methods that women used to self-induce abortion in the early twentieth century, when abortion was illegal.

This is not simply a subject confined to history books any more. Evidence suggests that self-induced abortion is rising once more, thanks in large part to political efforts that prevent women — especially poor women and women of color — from obtaining an abortion in a safe medical setting. In Texas, where efforts to curtail access to abortion have been particularly effective, researchers estimate that anywhere from 1.7 to 4.1% of women of childbearing age have attempted to induce an abortion themselves.

Researchers defined self-induced abortion as any attempt by a woman to end a pregnancy herself. The most common method of self-induced abortion among Texas women surveyed was to use the drug misoprostal, which is fairly effective in ending early pregnancies and is used by many clinics in the United States. The drug is widely available in Mexican pharmacies, and some Texas women are able to access the medication that way, although they are compelled to take it without medical supervision. However, not all women have the option of buying misoprostal across the border. Other common methods included herbs, homeopathic remedies, and punching oneself in the abdomen. This suggests that for many women, the state of reproductive healthcare has actually gone backwards in recent years.

On March 2, the Supreme Court heard arguments on the constitutionality of the Texas law HB2, which imposed significant restrictions on abortion providers. Since the law was passed in 2013, more than half of the clinics providing abortions in the state have shut down. When the Court decides on the matter of HB2, it should take into consideration both the past and present of self-induced abortion.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

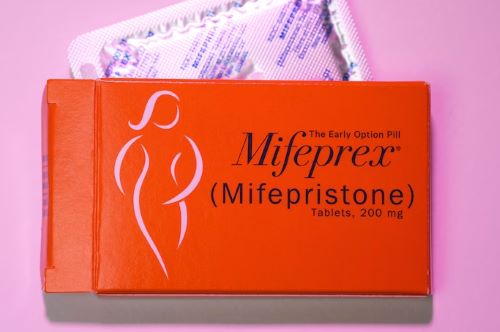

Pennyroyal, Mifepristone, and the Long History of Medication Abortions

Pennyroyal has been used as an abortifacient for over two thousand years.

Around midnight on September 16, 1866, Dr. W. A. Wilcox of Saint Louis, Missouri, was called to the home of “Mrs. L,” a thirty-year-old married mother of two. Mr. L had been out for the evening and returned home at eleven to find his wife unconscious. When Dr. Wilcox arrived, Mrs. L was pale and clammy; her breathing was heavy, her pulse was “feeble and quick,” and her extremities were cold. Her pupils did not contract when he shone light directly at them. Believing that she might have overdosed on opium, he forced “an emetic and fifteen to twenty drops of fluid extract of belladonna” down her throat every half hour and waited. After about three hours, Mrs. L began vomiting and regained consciousness. “The vomited matter,” Wilcox observed, “consisted of liquid smelling strongly of pennyroyal.”[1] When Mrs. L recovered enough to talk to the doctor, she told him she “had taken a teaspoonful of oil of pennyroyal” at nine in the evening before she went to bed. She had done this “in order to bring on her menses, which had been due several days.” Dr. Wilcox made no comment on this, except to note that Mrs. L began menstruating on September 17.

While “bringing on the menses” may sound to modern readers like code for abortion, it is impossible to say for certain that Mrs. L was trying to terminate a pregnancy. Regular menstruation was considered essential for a woman’s health, and many women took drugs – called “emmenagogues” – to bring on their menses if they were late. Most of the drugs used as emmenagogues could also be used as abortifacients. In Missouri in 1866, “bringing on the menses” was perfectly legal; inducing an abortion was not. Mrs. L may have lied to Dr. Wilcox about her intentions – or she may have been perfectly straightforward.

The drug in question, pennyroyal, is a species of mint with purple flowers. It smells like spearmint. And it has been used as an abortifacient for over two thousand years.

About half of all abortions in the United States are now medication abortions. In the past, that percentage was much higher. Up until the 20th century, most abortions, like Mrs. L’s, were medication abortions. A “surgical” abortion involved penetrating the cervix with some kind of sharp instrument. It was agonizingly painful and extremely dangerous. Even if the operation was successful at terminating the pregnancy, the ensuing infection could be deadly. Only with the advent of anesthesia and antisepsis in the late nineteenth century did surgical abortions become anything other than a desperate last resort. Most abortions were managed with medication, administered orally, vaginally, or topically. The medicines used were almost all herbal, and most had very long histories.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

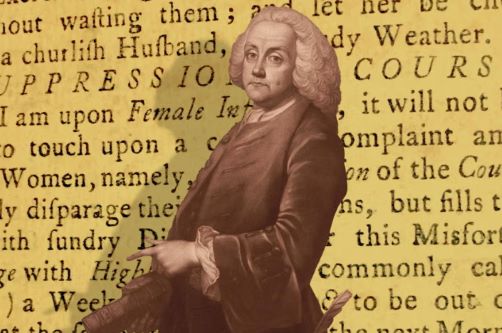

Ben Franklin Put an Abortion Recipe in His Math Textbook

To colonial Americans, termination was as normal as the ABCs and 123s.

The year was 1748, the place was Philadelphia, and the book was The Instructor, a popular British manual for everything from arithmetic to letter-writing to caring for horses’ hooves. Benjamin Franklin had set himself to adapting it for the American colonies.

Though Franklin already had a long and successful career by this point, he needed to find a way to convince colonial book-buyers—who for the most part didn’t even formally study arithmetic—that his version of George Fisher’s textbook was worth the investment. Franklin made all sorts of changes throughout the book, from place names to inserting colonial histories, but he made one really big change: adding John Tennent’s The Poor Planter’s Physician to the end. Tennent was a Virginia doctor whose medical pamphlet had first appeared in 1734.* By appending it to The Instructor (replacing a treatise on farriery) Franklin hoped to distinguish the book from its London ancestor. Franklin advertised that his edition was “the whole better adapted to these American Colonies, than any other book of the like kind.” In the preface he goes on to specifically mention his swapping out of sections, insisting that “in the British Edition of this Book, there were many Things of little or no Use in these Parts of the World: In this Edition those Things are omitted, and in their Room many other Matters inserted, more immediately useful to us Americans.” One of those useful “Matters” was a how-to on at-home abortion, made available to anyone who wanted a book that could teach the ABCs and 123s.

In this week’s leaked draft of a Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito wrote, “The inescapable conclusion is that a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions.” Yet abortion was so “deeply rooted” in colonial America that one of our nation’s most influential architects went out of his way to insert it into the most widely and enduringly read and reprinted math textbook of the colonial Americas—and he received so little pushback or outcry for the inclusion that historians have barely noticed it is there. Abortion was simply a part of life, as much as reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Franklin wasn’t even the first issuer of a math textbook on either side of the Atlantic to include among its materials a recipe for abortion, though his book certainly had the most reliable and explicit one. William Mather’s 1699 Young Man’s Companion also has one (the London book would inspire the very first arithmetic book to be printed in the colonies in 1705, by Franklin’s old boss Andrew Bradford). In Mather’s book, though, the recipe was short, misleading, and ineffective. It includes an entry for “Terms provoked,” a heading also found under comparable medical books with abortifacient concoctions (where the “term,” or period, needs “provoking”). Unfortunately for Mather’s readers, however, he prescribes “stinking Arach,” or goosefoot, which is an emmenagogue (an agent to stimulate or regulate menstruation) but not a reliable abortifacient. He also makes the even more dubious suggestion to “take a draught of White wine” under a full moon.

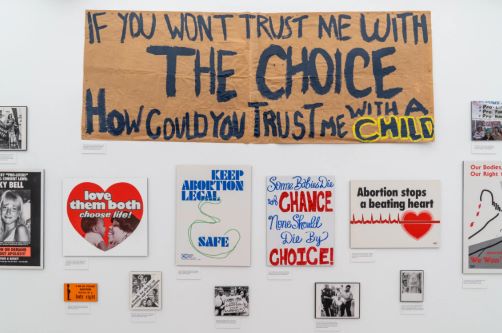

Women Have Always Had Abortions

History says the same thing over and over again.

Over the course of American history, women of all classes, races, ages and statuses have ended their pregnancies, both before there were any laws about abortion and after a raft of 19th-century laws restricted it. Our ignorance of this history, however, equips those in the anti-abortion movement with the power to create dangerous narratives. They peddle myths about the past where wayward women sought abortions out of desperation, pathetic victims of predatory abortionists. They wrongly argue that we have long thought about fetuses as people with rights. And they improperly frame Roe v. Wade as an anomaly, saying it liberalized a practice that Americans had always opposed.

But the historical record shows a far different set of conclusions.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, abortion was legal under common law before “quickening,” or when the pregnant woman could feel the fetus move, beginning around 16 weeks. The birth rate steadily dropped in the decades after the American Revolution, as couples sought to control the size of their families for a variety of reasons.

Abortion in the early stages of a pregnancy was common and generally not considered immoral or murderous. Along with breastfeeding, abstinence, the use of the rhythm method, vaginal douching and the use of herbs like pennyroyal or savin, which were believed to stimulate menstruation, abortion was considered part of the universe of what we now call “birth control.” By the 1820s, abortion services and contraceptive devices were advertised in newspapers with coded language.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Female Physicians in Antebellum New York City

“Female physicians” did a lot more than provide abortions.

In New York City newspapers in the 1840s and ʼ50s, reporters regularly decried the “female abortionist” who terminated pregnancies for the “base lucre” that it brought them, the “wretched creature who builds her fortune upon the misfortunes of her sex, caring no more for their sufferings of mind or body than does the butcher for the lives of the animals which it is his business to take.” In journals and at conferences, doctors affiliated with the American Medical Association influenced state legislatures to criminalize abortion in the 1850s and 1860s partially through their depictions of abortion providers as unskilled mercenaries who were driven by their lust for riches. Over and over again, critics of abortion—in the antebellum era as well as today—referred to those who terminated pregnancies as “abortionists,” despite the fact that many practitioners, both then and now, offered women a wide variety of reproductive services. It would be somewhat like calling dentists “tooth extractors” or dermatologists “mole removers,” equating practitioners with one procedure alone and simultaneously denigrating that procedure; it was a strategy to drive abortion providers out of business.

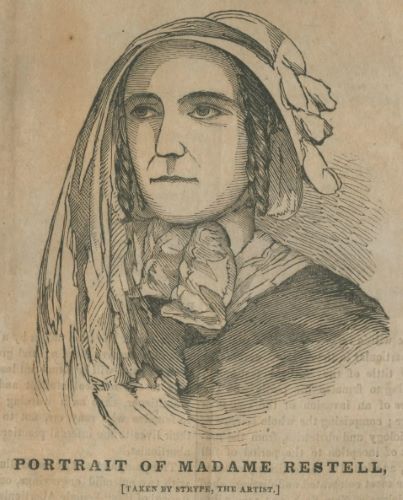

Rather than “abortionist,” the women I have been studying, all of whom operated in antebellum New York City, called themselves female physicians. Madame Restell (aka Ann Lohman) is the most well-remembered among them today, but there were many others. Longworth’s city directories of the late 1830s list an Elizabeth Mott, female physician, residing at 119 Spring Street. Others in the trade, including Mrs. Bird, Madame Costello, and Mrs. Sarah Anne Welch, one-time competitors of Restell, used the same language, both in city directories and in their advertisements. Madame Costello (aka Catharine Maxwell) published a book on the subject in 1860: A Female Physician to the Ladies of the United States: Being a Familiar and Practical Treatise on Matters of Utmost Importance Peculiar to Women.

None of these women had MDs. The first woman in the United States to receive formal medical training, Elizabeth Blackwell, did not earn her degree until 1849. In using the term, however, Restell and others of her ilk were not actually attempting to deceive. She and other New Yorkers would have understood a physician as a practitioner of medicine, as distinct from a surgeon, who was capable of operating on people, was likely to be formally trained, and was without question male. It is also the case that no medical doctor was licensed at the time; with a handful of short-lived exceptions, states simply did not issue medical licenses until later in the nineteenth century. It is highly unlikely that any unsuspecting patient would have believed that a female physician was formally trained. For Restell, and others, the phrase meant that she was a woman who provided medical services to other women, medical services that were almost exclusively related to that which made women distinct from men: their capacity for pregnancy. There is no question that “female physician” eventually became synonymous with “abortion” in the minds of many, but that should not detract from what those who used the phrase might have meant by it. In employing this language Restell and others like her were not simply describing their trade; implicitly they were also asserting their claim upon this term at a moment when medicine was changing, women losing ground in a domain that had largely been theirs for centuries, if not millennia.

Restell, Bird, Costello, and others provided services far beyond abortion precisely because they were in the business of treating women, no matter their needs. Like a more commercialized version of a midwife, many of them ran lying-in hospitals. Women came to them for their confinements and were delivered of their children. Despite lurid accounts to the contrary, many perfectly healthy babies left Restell’s home in the arms of their mothers. Sometimes female physicians arranged for babies to be adopted or to be placed with wet nurses, especially in the era before adoption was legally regulated. In an 1850 advertisement, Catharine Maxwell explained of her “Lying-in institution”: “Sore nipples or broken Breasts speedily healed by Mrs. Maxwell. Piles, falling of the womb, and all female diseases, attended to.” Female physicians also treated amenorrhea, or the suppression of the menstrual cycle, largely by selling emmenagogues. They also sold contraceptives: both condoms and herbal remedies. Finally, female physicians terminated pregnancies, either through the sale of abortifacients (usually some combination of tansy, rue, turpentine, ergot, and other herbs and resins) or through manually bringing on a miscarriage. Patients had the option of delivering the fetus in the lying-in hospital for a fee or returning to their homes and miscarrying there. I realize that focusing on what female physicians offered their patients other than abortion might have the effect of appearing to justify their practice via these other services. Instead what I am hoping to demonstrate is that female physicians of the antebellum era were in the business of serving all of their clients’ needs in a version of what we might today call “patient-centered care.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE PANORAMA

‘Hag of Misery’

Madame Restell is central to the story of how American women’s reproductive freedom was dismantled in the second half of the 19th century.

On a gloomy New England afternoon last winter, I climbed the stairs of the Adams Free Library, a grand Beaux Arts building in the Berkshires, to join in a historical commemoration. The venue was itself historic, a designated Civil War Memorial, its second floor originally the meeting hall for Post 126 of the Grand Army of the Republic, the association of Union veterans of Adams, Massachusetts. The post’s high-backed chairs are still on display, along with flags, swords, and sepia photographs of soldiers; the coffered ceiling is emblazoned with the names of bloody battles: Cold Harbor, Gettysburg, Antietam.

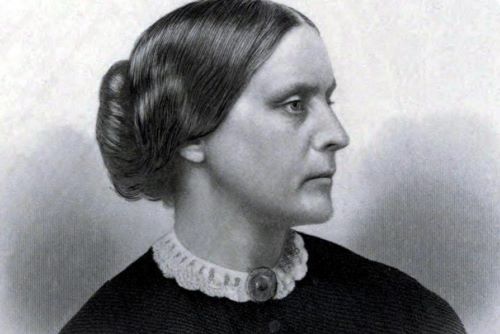

The day I visited, a crowd filled the rows of folding chairs and spilled into the aisles. We were there to honor a leader in another historic battle, Susan B. Anthony, on the occasion of her 203rd birthday. Anthony’s childhood home, a mile and a half away from the library, opened in 2010 as the Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. Its declared mission is “raising public awareness” of Anthony’s “wide-ranging legacy”—including her purported crusade against abortion.

You can spot the museum’s agenda in the offerings in its gift shop, from books (ProLife Feminism) to bumper stickers (WOMEN’S RIGHTS START IN THE WOMB), or in the inscriptions on the walkway’s bricks placed by donors, alluding to “the murder of the innocents.” On that February day at the library, Patricia Anthony, a museum board member and wife of a descendant, made that message explicit, enlisting an old civil war in service of a newer one. “Anthony and the women suffrage leaders allowed their previous work in the abolition antislavery movement to instruct them,” she told the assembled, not only to believe that “a human being could not be owned by another human being” but also that “a mother could not own her unborn child.” The antiabortion proprietors of the Birthplace Museum understand the uses of history.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK REVIEW

A Private Matter

Abortion and “The Scarlet Letter.”

As academic Arthur Riss puts it so well, “It is a truth now universally known that the scarlet letter upon Hester Prynne’s chest designates much more than adultery.” For another scholar, Laura Doyle, “Hester’s ‘A’ is a layered code,” one that gestures toward the concealed violence of American imperialism. And, in Franny Nudelman’s words, “Whether considered from a formal or a cultural vantage point, the letter’s power lies in its referential latitude, which allows it to accumulate and sustain a variety of readings under the rubric of its own simplicity. Its indeterminacy is indistinguishable from its inclusiveness, and both determine its critical stature.” Building on such formulations of the letter’s indeterminacy and layers of meaning, I propose another designation for the letter A, one that reflects or contains the following index from an 1846 issue of the National Police Gazette:

Abortion, prevention of

Abortion, seduction, and murder

Abortion, a felony

Abortionist, Restell the

Abortionist, convicted

Abortionists, detection of

Abortionists, horrible deeds of

Abortionists, more work of the

Abortionists, of New York

Abortionists, still at work

While I cannot prove that Nathaniel Hawthorne happened on precisely this page, it encapsulates a cultural phenomenon of which he must been aware. The letter folds the secret of a declined alternative within it, complicating the view that sex, pregnancy, and childbirth follow one from the other in an escapable train of consequences for Hawthorne’s protagonist.

The practice of abortion and its facilitation of nonreproductive sex in New England cities propelled medical and legal debates regarding pregnancy and its regulation in Hawthorne’s time, all of which played out in the press, in advertisements for abortifacients, in medical journals, and in the publicized trials of famed abortionist Madame Restell, the figure above named by the National Police Gazette.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAPHAM’S QUARTERLY

“She Had Smothered Her Baby On Purpose”

Enslaved women’s use of birth control, abortifacients, and even infanticide showed that they resisted by exerting control over their reproductive lives.

In Missouri in the spring of 1845, Vicey, an enslaved woman in her late twenties, gave birth to her fifth child, a son she named Stephen. In August of that same year, she killed him. Initially, Vicey claimed that Stephen died accidentally when she “fell into a deep sleep” with him in her arms. In preparation for burial, Stephen’s body “was placed away in the usual manner” and his death, attributed to his mother’s negligence, was not further investigated. Approximately six days after Stephen’s death, Vicey initiated a conversation with her enslaver, Catherine McMurtrey. Overwhelmed by guilt, Vicey confessed that “she had smothered her baby on purpose” by holding his “mouth and nose.” Prior to this confession, there is little to suggest that Stephen’s death was anything other than the accident that Vicey claimed it to be. As Catherine McMurtrey’s deposition testimony later revealed, however, Vicey asserted that her actions were not only deliberate, but they were also premeditated. When McMurtrey asked Vicey how long she had contemplated killing her son, she responded, “about three weeks.”

Enslaved women understood that their childbearing and rearing lay at the foundation of slavery. Consequently, preventing pregnancy or terminating a pregnancy represented more than an exercise of bodily autonomy, which was an act of resistance in and of itself; it represented a refusal to perform the labor deemed necessary for enslaved women. Vicey, like an unknowable number of enslaved women, consciously decided that she would not mother a child—to her, and others like her—her child’s death meant his freedom from slavery.

Although the specific impulses that led some enslaved women to kill their own children remain unknown, several women left no such doubts for their actions. Like Vicey, Margaret Garner saw infanticide as an act of emancipation. In 1856, Garner and her family ran away from the Kentucky plantations where they were enslaved. Their enslavers and Federal marshals tracked them to Ohio. Faced with capture and re-enslavement, Garner attacked her children, determined that they should not return to slavery and be “murdered by piece meal,” she decided that she “would much rather kill them at once and end their suffering.” In what was likely a spontaneous response to an immediate threat, Garner succeeded in killing her three-year-old daughter, Mary, but failed to kill her three other children.

Infanticide was an extreme means of maternal resistance. Preventing pregnancy and inducing abortion were other, likely more common but equally difficult to quantify, means of reproductive resistance. For enslaved women controlling their reproduction with preventatives and abortifacients represented the ultimate challenge to an enslaver’s authority as well as a reclamation of reproductive and bodily autonomy.

Constitutional decree ended the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808, effectively prohibiting the importation of enslaved people from outside the United States. In the early nineteenth century, a number of additional factors contributed to the acceleration of the domestic slave trade resulting in the forced relocation of over a million enslaved people from the Upper South to the Deep South and Southwest. Soil degradation in the Upper South from decades of tobacco cultivation, the invention of the cotton gin, the acquisition of millions of acres of land and subsequent forced removal of indigenous peoples to make land cheaply available to white settlers, and the invention of petit gulf cotton all played a role in the expansion of slavery and the plantation system. Consequently, enslaved women’s reproductive labor became even more important to the continuation of the system of slavery.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT AGE OF REVOLUTIONS

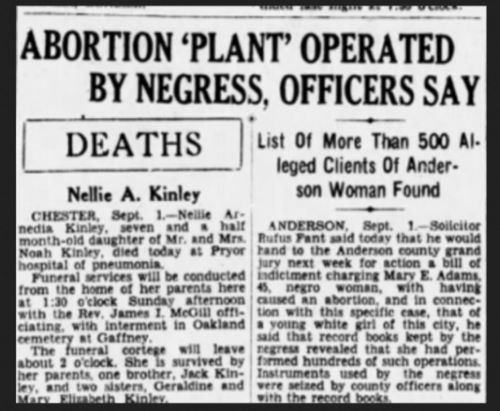

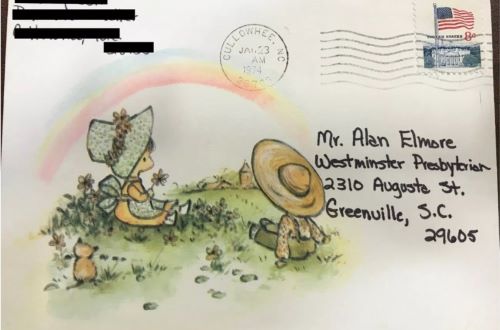

Abortion in Pre-Roe South Carolina

Uncovering Charleston’s “backstreet” abortion networks.

“Charleston was the place to come before Roe v. Wade, for abortions.”

Reminiscing about illegal abortion in South Carolina in the 1960s and early 1970s, this woman in her 60s, an oral history narrator, highlighted the roles of “backstreet” abortion networks in Charleston. She also told a story about a college friend who needed an abortion:

Because the medical university was here. Residents and interns would perform what we would call “No-Tell Motel” abortions….We came down for Citadel football and it was parents weekend or it was some kind of big weekend. And a girl who lived down my hall who was a senior had been dating a cadet, they were going to get married, she was in Charleston every chance she got. But that weekend or that Wednesday she came and asked if there was room in my car to come to Charleston and I said yeah….. We didn’t see ‘em at the parades, the Friday afternoon parade. We didn’t see ‘em at the football game Saturday. Sunday, when we were leaving to come back, all of us were there with our dates or whatever. She showed up and she looked God-awful, and we just thought, “Oh my god they had major fights,” because she had cried so much that her eyes were almost, she could see out of ‘em but you obviously knew she’d been crying. She said nothing on the way back to school… And we didn’t say an awful lot because we didn’t know what had gone on. Get back in and 3 o’clock the next morning, there’s a pounding on the room door across the hall from us …This girl was hemorrhaging. And I remember going into her room and looking at her and she’s lying on the bed and the bed is full of blood. She’d had an abortion, she’d gone up to Rivers Avenue [in North Charleston], to one of the motels.

This narrative was collected in 2016 by researchers from College of Charleston’s Women’s Health Research Team (WHRT), an interdisciplinary group of students and faculty that investigates health issues in order to empower women and girls in South Carolina and beyond.

Faculty and students on this project, entitled “Reproductive Health Histories,” gathered 70 oral histories focusing on reproductive health from women in South Carolina’s Lowcountry. Although we asked basic questions on fertility control and abortion, we were astounded at the in-depth knowledge about illegal abortion that our narrators demonstrated. These women provided intriguing glimpses into abortion realities in South Carolina’s recent past. They told us about the complexities of abortion: the diverse methods employed, the various spaces of abortion, and the roles played by “professional” abortionists.

Women over 50 and 60 had particularly telling things to say about abortion before it was decriminalized. They related a variety of abortion methods, including home or folk remedies such as herbal potions and turpentine consumption, surgical procedures at “professional” offices, and other self-inflicted mechanical procedures. According to one woman discussing the 1960s in Charleston, “you could go to one of these root doctors and you could get medicine for anything, and you could get medicine for preventing pregnancy or ending pregnancy.” Another told us:

I heard horror stories, just bits and pieces of people in the community that had gone off and had abortions in different methods. The clothes hanger method, of going to the doctor and how horrible that was. The people bleeding to death and getting infections. Stuff like that.

These remembrances of illegal abortion also raised additional questions: Who were the abortion providers? Where, other than “no-tell motels,” did abortions occur? How many illegal abortionists were brought to trial from 1900 to 1973?

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

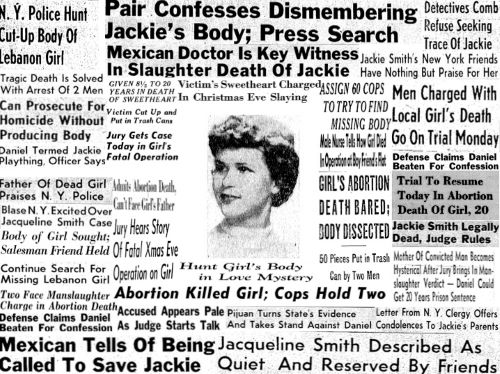

A Christmas Abortion

On Christmas Eve 1955, Jacqueline Smith died from an illegal abortion at her boyfriend Thomas G. Daniel’s apartment.

On Christmas Eve 1955, Jacqueline Smith died from an illegal abortion at her boyfriend Thomas G. Daniel’s apartment.

Jacqueline Smith was born in Lebanon, Pennsylvania in 1935. A quiet, driven and talented artist, she graduated from high school in 1953 and moved to New York City where she intended to become a fashion designer. In June of 1955, Jacqueline began to date Thomas, a sales trainee in a riding equipment shop. Although Jacqueline spent most nights in Thomas’s apartment, the stigma surrounding cohabiting and having premarital sex was so great that she kept an apartment with three other women in order to maintain appearances.

In November of 1955, Jacqueline discovered she was pregnant. When she shared the news of her pregnancy with Thomas, she hoped that he would marry her. At that time, unmarried pregnant women faced harsh consequences for their sexual activity, including job loss and stigmatization. Unwed mothers, pilloried and pathologized, faced limited prospects for marriage even as their children had the word “illegitimate” stamped on their birth certificates. Many young women went to maternity homes in other towns—their families would make excuses for their absence to hide the shame of unwed pregnancies—where they would have the baby and then give the child up in a closed adoption, all done in secrecy. Upon returning home, these women were expected to pretend that the pregnancy never happened and to make the most out of a second chance at respectability.

Thomas did not want to marry Jacqueline and began looking for a means to terminate her pregnancy. Over the next month, he asked colleagues and friends if they knew how to cause a miscarriage. Thomas convinced Jacqueline to take abortifacient pills, but these did not work. Jacqueline in the meantime went to her OBGYN twice for examinations, made plans for future checkups, and made arrangements to deliver the baby.

On Christmas Eve 1955, Thomas paid $50 to Leobaldo Pijuan, a hospital attendant, to perform an illegal abortion. Legal abortions—done at hospitals—required approval from a committee of doctors, which acted as deterrents for women seeking elective abortion. Hospitals usually authorized abortions in rare cases when a pregnancy endangered the health of the mother. Those unable to obtain hospital abortions would turn to underground abortionists, some of whom were skilled and some of whom were unskilled and whose lack of medical training physically endangered women. Leo Pijuan was one of the latter.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NOTCHES

How TV Lied about Abortion

For decades, dramatized plot lines about unwanted and unexpected pregnancies helped create our real-world abortion discourse.

n the second season of Mad Men, perpetually desperate Harry Crane needs to prove himself useful to his colleagues at Sterling Cooper. When he hears the CBS drama The Defenders is losing advertisers because of an abortion plot line — a 1962 real-world event — he tries to convince a lipstick company to buy airtime. The Belle Jolie executive balks at “entering the debate,” leaving Harry aghast at the lack of foresight. “Women,” he says incredulously, “will be watching!”

He was right, but so was the Belle Jolie exec.

For decades, abortion on television was largely depicted as a debate in narrative form, one that pitted melodramatic anti- and pro-abortion rights stances against each other through characters audiences knew and loved. Gretchen Sisson and Katrina Kimport, researchers at the University of California San Francisco, argued in 2014 that, over time, these narratives collectively created “common cultural ideas about what pregnancy, abortion, and women seeking abortion are like.” The result, according to Sisson and Kimport, was an inaccurate picture of who seeks abortions, and why.

Fictional abortions were also overdramatized. From the origins of television all the way through the past decade, overwhelmingly male TV writers created plot lines that framed abortion as a moral issue, amping up conflict for maximum emotional journeys. It isn’t hyperbolic to say that television significantly changed the way America understood abortion and, as a result, deeply influenced public policy.

Andrea Press, a communications professor who documented this relationship in a 1991 study, concluded that “when the moral language adopted by television differs from that of viewers, television viewing influences viewers to adopt its terms.” The medium is not a passive bystander in our social debates; it is an active participant, shaping attitudes and action.

In other words, the stories we see on TV help create who we are.

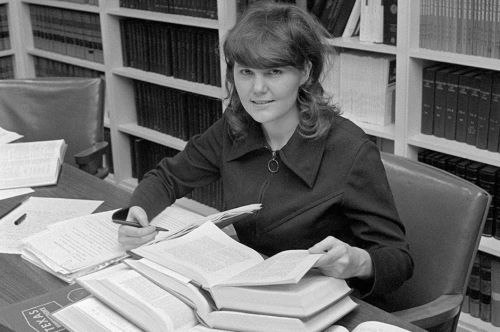

To Have and to Hold

Griswold v. Connecticut became about privacy; what if it had been about equality?

When Louise Trubek and her husband, Dave, drove from New Haven to Washington to listen to oral arguments before the Supreme Court in Trubek v. Ullman, she was pregnant. The Trubeks had met at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and married in 1958. The next year, while they were both students at Yale Law School, they filed a complaint against the State of Connecticut about a statute that prevented their physician, C. Lee Buxton, the chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Yale Medical School, from discussing contraception with them. They wanted to have children one day, according to the complaint, but “a pregnancy at this time would mean a disruption of Mrs. Trubek’s professional education.” By the time that Trubek v. Ullman reached the Supreme Court, in the spring of 1961, Louise Trubek had graduated from law school and was ready to start a family. The case was dismissed, without explanation.

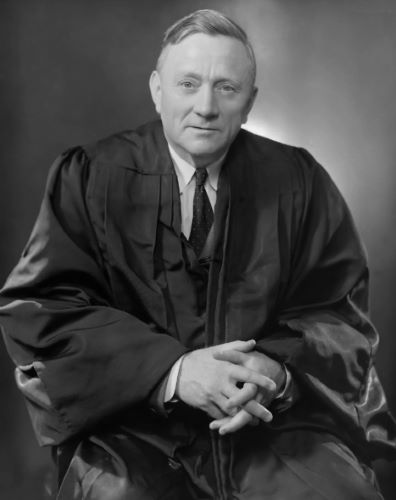

This spring marks the fiftieth anniversary of the case that went forward instead: Griswold v. Connecticut. (“We became the footnote to the footnote,” Trubek told me.) In Griswold, decided in June, 1965, the Supreme Court ruled 7–2 that Connecticut’s ban on contraception was unconstitutional, not on the ground of a woman’s right to determine the timing and the number of her pregnancies but on the ground of a married couple’s right to privacy. “We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights,” Justice William O. Douglas wrote in the majority opinion. “Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred.”

In the half century since Griswold, Douglas’s arguments about privacy and marriage have been the signal influence on a series of landmark Supreme Court decisions. In 1972, Eisenstadt v. Baird extended Griswold’s notion of privacy from married couples to individuals. “If the right of privacy means anything,” Justice William Brennan wrote, “it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.” Griswold informed Roe v. Wade, in 1973, the Court finding that the “right of privacy . . . is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” And in Lawrence v. Texas, in 2003, Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing a 6–3 decision overturning a ban on sodomy, described Griswold as “the most pertinent beginning point” for the Court’s line of reasoning: the generative case.

A few weeks ago, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Obergefell v. Hodges, a consolidation of the petitions of four couples seeking relief from state same-sex-marriage bans in Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee. The federal Defense of Marriage Act was struck down by the Court in 2013, in U.S. v. Windsor, a ruling in which Kennedy cited and quoted his opinion in Lawrence. But bans still stand in thirteen states. In 2004, Ohio passed a law stating that “only a union between one man and one woman may be a marriage valid in or recognized by this state.” The Ohioans James Obergefell and John Arthur had been together for nearly twenty years when Arthur was diagnosed with A.L.S., in 2011. In 2013, they flew to Maryland, a state without a same-sex-marriage ban, and were married on the tarmac. Arthur died three months later, at the age of forty-eight. To his widower, he was, under Ohio law, a stranger. The Court is expected to issue a ruling in June.

The coincidence of the fiftieth anniversary of the Court’s ruling in Griswold and its anticipated decision in Obergefell makes this, inescapably, an occasion for considering the past half century of legal reasoning about reproductive and gay rights. The cases that link Griswold to Obergefell are the product of political movements that have been closely allied, both philosophically and historically. That sex and marriage can be separated from reproduction is fundamental to both movements, and to their legal claims. Still, there’s a difference between the arguments of political movements and appeals to the Constitution. Good political arguments are expansive: they broaden and deepen the understanding of citizens and of legislators. Bad political arguments are as frothy as soapsuds: they get bigger and bigger, until they pop. But both good and bad constitutional arguments are more like blown-in insulation: they fill every last nook of a very cramped space, and then they harden. Over time, arguments based on a right to privacy have tended to weaken and crack; arguments based on equality have grown only stronger.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORKER

Judge Kacsmaryk’s Medication Abortion Decision Distorts a Key Precedent

One of the cases on which the judge relies said the opposite of what he claims it did.

Late on Wednesday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit issued a partial stay of Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s ruling suspending the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of mifepristone, one of the two drugs used in medication abortions and a drug used in miscarriage care. The decision will allow mifepristone to remain on the market, but it will keep changes the FDA made to the drug’s approved use in 2016 blocked, as well as the agency’s 2021 finding that the drug could be distributed by mail.

Kacsmaryk’s opinion was riddled with historical inaccuracies and distortions — none more egregious than his reference to the 1936 decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in United States v. One Package. Kacsmaryk states that the decision affirmed the illegality of shipping abortion-related devices by quoting two short passages.

But this is wrong: One Package did not concern mailing devices that the recipient could use for an abortion — instead, the case centered on the legal right of physicians to import devices for research and prescription, when the well-being of their patients was at stake. The case was a win for medical research on contraception and women who wanted control over their fertility. The case’s background and history expose how Kacsmaryk fundamentally misinterprets the case, and why his reliance upon it to impede the use of mifepristone is ill-informed.

In June 1932, Margaret Sanger, then the best-known advocate for contraception, set in motion what would become United States v. One Package.

After decades of advocacy, Sanger was frustrated with the slow progress toward passing legislation to enable unfettered access to contraception for women (diaphragms and cervical caps, specifically). So, she and free-speech advocate and attorney Morris Ernst set up a test case to assess the medical legitimacy of contraception and the rights of doctors to research medical devices.

The medical director of the Sanger-led Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, Dr. Hannah Stone, agreed to receive a package of pessaries (a.k.a. diaphragms) from a Japanese doctor, Sakae Koyama, whom Sanger had befriended on her travels to Japan. Section 305a of the U.S. Tariff Act of 1930 had recently extended the 1873 Comstock Act to foreign imports of materials perceived as obscene. And so, Sanger and Stone anticipated that the U.S. Customs Office would seize the shipment of pessaries under this law. Then, Ernst would defend Stone and the right to import contraceptives in court.

And that is precisely what happened.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

(Still Being) Sent Away: Post-Roe Anti-Abortion Maternity Homes

In the years before Roe v. Wade, maternity homes in the United States housed residents who, upon giving birth, often relinquished their children for adoption.

In the years before Roe v. Wade, and in a context of severe stigma of out-of-wedlock pregnancies, maternity homes in the United States housed residents who, upon giving birth, often relinquished their children for adoption. One consequence of the legalization of abortion in 1973 was that fewer American women and girls were “sent away” to maternity homes for the duration of their pregnancies. Far from a relic of the pre-Roe past, though, maternity homes in the 1980s and 1990s remained a feature of the US’s landscape, albeit still well hidden. These institutions differed from their predecessors, however, for many of these newer homes were explicitly affiliated with the anti-abortion movement. Indeed, numerous post-Roe maternity homes enjoyed close relationships with local crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) – right-to-life institutions that similarly worked to dissuade women from terminating their pregnancies. Post-Roe maternity homes also partnered with state and private adoption agencies to make adoption a viable alternative to abortion, and some were sponsored by Religious Right spokespeople such as Jerry Falwell, Billy Graham, and Pat Robertson.

In the hopes of “saving” those “at risk” of terminating their pregnancies, anti-abortion maternity homes advertised themselves as safe havens, offering housing and other resources to women and girls experiencing crisis pregnancies for little or no fee. While some pregnant people may have found much-needed comfort and security in these services, other residents’ stays were marred by abuse. Deliberately hidden from public view, little is known about these ever-elusive institutions. Nevertheless, the evidence we do have from residents’ testimonies and anti-abortion literature offers a glimpse into the anti-abortion movement’s evolving strategies in the 1980s and 1990s and sparks pertinent questions about women’s reproductive agency.

Political scientist Laura Hussey describes maternity homes as part of the anti-abortion movement’s “service” branch because, like CPCs, they worked to challenge the accusation that anti-abortion activists did little to temper the financial and emotional burdens of pregnancy and childrearing. Operating against a backdrop of welfare cuts, maternity homes hoped to provide an attractive alternative to abortion by providing the comfort and security necessary to make carrying one’s pregnancy to term possible. For instance, Bayard House, an independent maternity home in Wilmington, Delaware proclaimed that many of its residents felt “deprived of a free choice in deciding whether or not to keep their pregnancies because they lack[ed] necessary support or resources.” As this appropriation of the feminist language of reproductive “choice” makes clear, maternity homes sought to demonstrate their concern for pregnant women as well as fetuses: an increasingly salient anti-abortion tactic in the 1980s and 1990s.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

Who Provided Care

San Francisco’s Queen of Abortions Gets Her Moment of Recognition

Two new biographies look at the life of Inez Burns, an uncompromising and extravagant turn-of–the-century woman.

It was there, in the relative tranquility of her little cottage in the Women’s Department at San Quentin at Tehachapi and later at the federal prison at Alderson, in the twilight of her sixties, that notorious abortionist Inez Burns had her feminist awakening. More important than making money (and she loved making money), her work helped women to take charge of their bodies in a world controlled almost entirely by men — men who wanted to have their cake, eat it, and then moralize about the wickedness of baking in between visits to their mistresses.

She saw the church and its second class treatment of women as complicit in women’s suffering; all those years of watching Catholic women enter her clinic, trailing six children and desperate to prevent a seventh, left a sour taste in Burns’ mouth, even more so than their legislative efforts to put her out of business. In her eyes, the church was adding generations of misery around the world for the pleasure of men, and making slaves of half of the population by giving men unchecked control over the reproductive systems of their wives, girlfriends, and daughters. What had for so long been purely business had become a crusade for her, and when she got out of prison, she went right back to work.

Burns never met a man she couldn’t charm until she crossed paths with pathologically ambitious attorney Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, who aimed to launch his political career out of the ashes of her empire. He couldn’t have picked a tougher nut to crack — San Francisco’s “Queen of Abortions” was as tough as the steel needles she used to perform her services on thousands upon thousands of women. Burns’s improbable, fantastically scandalous trajectory took her from humble beginnings in a San Francisco slum to a Pittsburgh pickle packing plant, a fateful manicurist job at the ritzy Palace Hotel, and then onto her lifelong career as the West Coast grande dame who — assisted by her team of nurses in crisp white uniforms — provided safe, hygienic abortions on demand to WWI war widows, rape survivors, scorned lovers, Hollywood stars, and the Gilded Age elite alike. She made unholy amounts of money, bribed the cops with abandon, changed husbands like hats, sashayed through theater premieres in Paris couture, had a run in with one of Al Capone’s Mafia thugs, almost certainly dispatched one of her own husbands with arsenic — and she did it all with so much style, cunning, and hard-nosed grit that, for decades, she was untouchable.

Despite her larger-than-life influence, Inez Burns remains an obscure figure in American history, even within the canon of feminist scholarship. The thought of digging up Burns’ secrets and connecting the scattered dots of her extraordinary life makes for an intimidating prospect, considering the secretive nature of her business. (She often employed code words like “glantham” for cash, “Emily” for phantom pregnancies, and “ni-dash” for “don’t you dare open your mouth!” for an extra layer of security beyond her hidden staircase, trapdoors, and private cash reserves). However, the unsinkable Mrs. Burns’ tale of woe and wickedness captivated not one, but two authors in recent memory. 2017 saw the release of Lisa Riggin’s San Francisco’s Queen of Vice: The Strange Career of Abortionist Inez Brown Burns, and this month sees the release of Stephen G. Bloom’s The Audacity of Inez Burns: Dreams, Desire, Treachery, & Ruin in the City of Gold. It’s surely no accident that both books were released within spitting distance of the 45th anniversary of Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that effectively legalized abortion in the United States.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE OUTLINE

Abortion’s Past

Before Roe, abortion providers operated on the margins of medicine. They still do.

Life before Roe. For those of us who lived it, it is hard to believe there is already a generation that can only imagine it. It is the stuff of women’s cinema, unveiling conversations, demonstrations, stories cast in print or still untold.

I was a teenager back then, pregnant and desperate. Too terrified to make the midnight trip to the back alley with a password and hundreds of dollars (which I didn’t have anyway). The “therapeutic abortion” committee—strangers who prodded my body, exposed my deepest secrets, then told me “no.” The pain and violence of carrying a pregnancy to term against my will. The insidious punishment of sharing a hospital room with nursing mothers, as I nursed the indelible memory of her inked footprint before she was whisked away. Abandoned by my family, left to pick up the pieces of a broken life. And to think I was one of the “lucky” ones—still alive—not poisoned, perforated, hemorrhaging, raped, or dead, like thousands of other women.

But life before Roe is not only about the dark legacy of back alley butchers and women denied. It is also a story of resistance, of a movement of disparate organizations and individuals who operated underground and pressed in the streets, courts, and legislatures for safe and legal abortion. Carole Joffe’s Doctors of Conscience examines this historical period through the eyes of 45 mainstream physicians who began practicing medicine during the 30 years before Roe. Diverse in their origins and motivations, these physicians were each eventually compelled by what they witnessed to become involved in abortion activity, risking their careers and personal lives. They were perhaps a minority among the many “heroes” of the illegal abortion era. But as Joffe points out, precisely because they were part of the mainstream medical profession, “their stories tell us most about the difficult history and uncertain place that abortion services have had within the larger medical establishment.”

Doctors of Conscience does not offer detailed accounts of individual women seeking abortions, or the oft-quoted public health statistics on the morbidity and mortality of illegal abortion. Rather, Joffe captures the “lengths to which women would go” to control their reproduction in horrific snapshot images that come from the health professionals who treated them: emergency rooms teeming with women bleeding from corrosive agents, broken Coke bottles, catheters, and coat hangers; late-night operating rooms crowded with stretchers holding women who waited to have their instrumented uteruses evacuated or removed; a woman delivered to the emergency room with a paper bag containing eight feet of her intestines. This collective human suffering is attended by a palpable paranoia permeating the wards in which it occurred—the pervasive police presence; physicians, under the threat of the law, forced to grill patients about the identities of their abortionists in the moments before they died. No less chilling is the insidious misogyny that stigmatized these women, and devalued their lives. As one physician recounts, the special wards of public hospitals where women suffered and often died from septicemia, or overwhelming infection, were referred to as “septic tanks.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT BOSTON REVIEW

Before Roe v. Wade, U.S. Residents Sought Safer Abortions in Mexico

Transnational networks have long helped pregnant people navigate treatment options.

In the years after World War II, public frenzy developed over the proliferation of “abortion mills.” Across the country, well-known and at times well-respected abortion providers were raided and clandestine clinics closed. These aggressive tactics emerged during a period when, as one historian put it, there was “an assault on female independence” and an embrace of “traditional motherhood” as men returned from war looking for work and marriage.

While some women enlisted all-manner of grotesque tools or crude potions to end their pregnancies, others began traveling to Mexico for abortion services. Although the Catholic Church held some sway over the Mexican government’s position on birth control, there were fissures as the Mexican government sought to distance itself from the church in the early years of the 20th century. At the same time, the border region provided cover for such illicit activities as gambling, prostitution and alcohol consumption during Prohibition.

And so, by the 1940s, abortion providers began appearing along Mexico’s northern border in cities such as Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana, largely to serve U.S. residents in search of abortion care. They weren’t legal, but police, judges and attorneys in Mexico took kickbacks and turned a blind eye to the emerging business.

By the 1960s, with assistance from various organizations, including the Society for Human Abortions (SHA) in San Francisco and the Clergy Consultation Service (CCS) headquartered in New York, women from all over the United States received information about reliable abortion providers in Mexico. Some women drove hundreds of miles, while others took “abortion flights” — leaving Friday afternoon and returning Sunday morning — to the El Paso airport and crossed the border by foot or taxi to El Paso’s sister city Ciudad Juárez for the procedure.

People from all walks of life contacted SHA and CCS for guidance on finding reputable abortion providers in Mexico. One father pleaded with Patricia Maginnis, the feminist co-founder of SHA, to help him find an abortion practitioner for his young daughter who had become pregnant after a sexual assault. A mother wrote a letter to the organization asking for help when she could not physically or financially bear to have a fifth child. SHA received countless letters from college-age women seeking to end unplanned pregnancies because they wanted to complete their education on their own terms.

While it is difficult to know the class status and racial demographics of those seeking abortion information via SHA and CCS referrals — it was an illicit service after all — from missives directed to SHA, we can glean that people were able to scrape together the $250-$300 needed for the procedure and the additional $100 for transportation and lodging. It was a significant sum of money ($300 in 1965 would be approximately $2,500 in today’s dollars.) Still, it was minimal compared to the then-thousands of dollars women might spend trying to receive authorization from doctors and psychiatrists for abortions classified as legal in the United States.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

The Women of Jane

The story of an underground abortion service that operated pre-Roe vs. Wade.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade, abortion was illegal throughout most of the country. But that doesn’t mean women didn’t get them.

In 1965, an underground network was formed in Chicago to help pregnant women get abortions. At first, they connected women with doctors willing to break the law to perform the procedure. Eventually, they were trained and began performing abortions themselves. The group called itself “Jane.” Over the years, Jane performed more than 11,000 first and second-trimester abortions.

This story first aired in 2018 on All Things Considered. For more info check out Leslie Reagan’s book When Abortion Was a Crime and Laura Kaplan’s, The Story of Jane. Banner image: (From left) Martha Scott, Jeanne Galatzer-Levy, Abby Parisers, Sheila Smith and Madeline Schwenk were among the seven members of Jane arrested in 1972.

The transcript for this episode is available here in English.

Abortion Was Illegal. This Secret Group Defied the Law.

We tell the story of the Jane Collective, which provided thousands of illegal abortions fin Chicago rom 1969 to 1973, before Roe v. Wade.

The Supreme Court has reversed Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that established the constitutional right to abortion. We tell the story of the Jane Collective, which provided thousands of illegal abortions from 1969 to 1973.

Using tactics worthy of a spy novel, the Jane Collective carried out thousands of abortions in Chicago from 1969 to 1973. A woman seeking to end her pregnancy could leave a message on an answering machine. A “Callback Jane” phoned her, collected information and passed it to a “Big Jane.” Patients would be taken first to one address, “the front,” for counseling. They were then led, sometimes blindfolded, to another spot, “the place,” where an abortion was performed.

Failing to Embed Abortion Care in Mainstream Medicine Made It Politically Vulnerable

Actions by the medical profession in the 1970s still reverberate today.

By the time of Roe, a majority of the medical community supported legal abortion — but not necessarily those who provided it, who remained stigmatized and thought to be more closely associated with a back-alley quack than a respected medical professional. Beyond their discomfort with abortion providers, the largely White, male and conservative medical profession of that era was ambivalent about incorporating abortion care for other reasons.

The threat that abortion posed to conventional medical authority was one. As a doctor complained at an American Medical Association (AMA) meeting in 1970, where legalization was under discussion, “Legal abortion makes the patient truly the physician: she makes the diagnosis and establishes the therapy.” That this scenario would typically involve a female patient dictating a course of treatment to a male doctor only compounded the discomfort in an era when medical authority was almost entirely reserved for men and motherhood was considered normative for women.

Moreover, the evident association of abortion with social movements — both for and against legal abortion — was disturbing to many in a conflict-averse profession. On one hand, many in medicine were less than sympathetic to the feminist activists demanding “abortion on demand” in the years leading up to Roe. On the other hand, four days after the Roe decision was announced, the Church amendment, which offered “conscience protections” for health-care workers who refused to participate in abortion, was reintroduced in Congress (and passed several months later). This quick action sent a signal that this procedure would be more scrutinized than the rest of medicine.

What is striking about the years after Roe affirmed a constitutional right to abortion were the measures that were not taken.

Very few medical organizations took the steps that would normally be expected after a major policy change. Most medical groups issued no guidelines, standards or even statements of support. Leaders within OB/GYN did not make any effort at education, for legislators or the general public, about the health benefits of legal abortion. Most significantly, the organizations charged with establishing residency requirements in OB/GYN did not mandate routine training in abortion for another 20 years. Even then, Congress immediately weakened the mandate. In short, at a crucial time, medical leaders passed on the opportunity to fully integrate abortion care into mainstream medicine.

The significant violence and harassment that is now central to abortion politics in America did not begin in earnest until 1988, some 15 years after Roe, when a new organization, Operation Rescue, began blockades and clinic invasions. Days before the first abortion doctor was assassinated in 1993, Randall Terry, the organization’s founder, told a crowd, “We’ve found the weak link is the doctor. … We’re going to expose them, we’re going to humiliate them.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

Learning and Not Learning Abortion

The fact that most doctors like me don’t know how to perform abortions is one of the greatest scandals of contemporary medicine in the US.

I don’t know how to perform an in-clinic abortion (also known as a surgical abortion), or how to counsel a person about one; I also don’t know how to provide follow-up care, or how to identify and manage the rare complication that might arise—at least, no more than any other literate adult with access to the internet. The trouble is, I am a physician of internal medicine: my theoretical purview is all the organs of the adult body.

It’s true that my clinical job is what the poet John Berryman would’ve called “thinky”—fewer hands-on procedures; more diagnosis, counseling, and prescription—but I ought to know more than I do. Surgical abortion is a common procedure performed on an organ half the people on the planet possess. The fact that most doctors like me—and even my colleagues in obstetrics and gynecology—don’t know how to perform abortions is one of the great scandals of contemporary medicine in the US. As the recent Dobbs decision accelerates the 21st century’s steady dismantling of abortion rights in America, it’s worth examining how the medical profession has, for generations, systematically limited the extent to which doctors come to learn and practice the procedure.

Currently only 24 percent of ob-gyns nationally provide abortions. The American Medical Association (AMA) continues to refuse to make abortion education a curricular mandate across accredited schools, and half of all medical schools provide either zero or just one lecture on abortion. Even among specifically ob-gyn programs, only half provide routine abortion training to residents; there is currently no mandate that education or training on abortion be provided during students’ ob-gyn clinical rotations. Eighty-nine percent of US counties have no abortion providers in them at all. It is not by accident that the medical profession on the whole is bad at abortion and its accompanying care, counseling, and discourse.

With the end of the Roe era upon us, I share the general worry about a rise in unsafe abortions for people without other options, although I’m also heartened by the fact that the patients I know are often astonishingly creative at obtaining medications, procedures, and forms of care that their doctors can’t or won’t provide, often with great adaptability and courage. What worries me more is that given the moral authority still accorded to us doctors—the second most respected profession in the US for its ethics, after nurses, according to Gallup—our collective ineptitude around abortion might make it seem like maybe there isactually something wrong or untoward about abortion itself, that maybe the “safe, legal, and rare” Clintonism really is the decorous response. After all, there’s a reason why contemporary doctors are also inept at bloodletting, phrenology, and lobotomy. Mustn’t incompetence signal an essential noncentrality, a certain dodginess?

Meet the Queen Bee of Victorian Abortionists

The notorious Madame Restell lived large and fearlessly in a century not so far, far away.

Jennifer Wright opens her painfully timely biography of Madame Restell, the notorious “abortionist of Fifth Avenue,” with her final arrest, in 1878, at the hands of the anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock. For Comstock, a Victorian zealot who smeared his sexual obsessions all over American life well into the 20th century, this was the climax of an epic struggle between Satan’s handmaiden and his flaming sword of righteousness. To Restell, a grandmother in her late 60s, it was merely the latest in a long line of tedious interruptions to her business.

Born Ann Trow in 1811 in the Cotswolds village of Painswick, she became a maid-of-all-work, a grueling job that carried the constant threat of being “seduced or outright raped.” Although Ann avoided this fate, the experience was formative: Throughout her life, she felt sympathy for servants in trouble, and offered the members of her own staff better-than-average pay and working conditions. At 16, Ann married a tailor, and in 1831, with their toddler in tow, the family sailed for New York alongside thousands of other immigrants competing for work. They scraped along for two years in the Five Points slum before Ann’s husband, an alcoholic, died of typhoid.

In an era when some 10,000 prostitutes worked a city of a quarter-million people, the pretty young widow avoided sin and addressed its consequences instead. She befriended a pill compounder — a role Wright likens to a modern-day supplement shill — who taught her to assemble drugs from ingredients like pennyroyal, rue, Queen Anne’s lace, oil of tansy and turpentine, which have a long, perilous history of ending pregnancies. He may also have been the one who taught her to perform surgical abortions using whalebone. Ann apparently had a knack for gauging the dosage and mitigating the taste, and before long she struck out for herself, helped by her brother and her second husband, an easygoing, irreverent Russian immigrant named Charles Lohman. Together they dreamed up the persona of the exotic, Paris-trained “Madame Restell” and began to advertise — but the business was Ann’s alone. For more than 40 years, despite vociferous opposition, several arrests and stints in jail, she pursued her calling, terminating unwanted pregnancies and helping place unwanted babies, and became a city fixture. When attacked in the press, Restell published her own sharp retorts — today, Wright suggests, she “would be fighting on Twitter constantly.” Every denunciation, every trial, served as an advertisement for her services.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Legal Frameworks

Abortion in American History

How do ideological debates on gender roles influence the abortion debate?

Of all the issues roiling the ongoing culture wars, abortion is both the most intimate and the most common. Almost half of American women have terminated at least one pregnancy, and millions more Americans of both sexes have helped them, as partners, parents, health-care workers, counselors, friends. Collectively, it would seem, Americans have quite a bit of knowledge and experience of abortion. Yet the debate over legal abortion is curiously abstract: we might be discussing brain transplants. My files are crammed with articles assessing the question of when human life begins, the personhood of the fetus and its putative moral and legal status, and acceptable versus deplorable motives for terminating a pregnancy and the philosophical groundings of each one—not to mention the interests of the state, the medical profession, assorted religions, the taxpayer, the infertile, the fetal father, and even the fetal grandparent. Farfetched analogies abound: abortion is like the Holocaust, or slavery; denial of abortion is like forcing a person to spend nine months intravenously hooked up to a medically endangered stranger who happens to be a famous violinist. It sometimes seems that the further abortion is removed from the actual lives and circumstances of real girls and women, the more interesting it becomes to talk about. The famous-violinist scenario, the invention of the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson, has probably inspired as much commentary as any philosophical metaphor since Plato’s cave.

Abortion as philosophical puzzle and moral conundrum is all very well, but what about abortion as a real-life social practice? Since the abortion debate is, theoretically at least, aimed at shaping social policy, isn’t it important to look at abortion empirically and historically? Opponents often argue as if the widespread use of abortion were a modern innovation, the consequence of some aspect of contemporary life of which they disapprove (feminism, promiscuity, consumerism, Godlessness, permissiveness, individualism), and as if making it illegal would make it go away. What if none of this is true? In When Abortion Was a Crime, Leslie J. Reagan demonstrates that abortion has been a common procedure—“part of life”—in America since the eighteenth century, both during the slightly more than half of our history as a nation when it has been legal and during the slightly less than half when it was not. Important and original, vigorously written even down to the footnotes, When Abortion Was a Crime manages with apparent ease to combine serious scholarship (it won a President’s Book Award from the Social Science History Association) and broad appeal to the general reader.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE ATLANTIC

The History of Outlawing Abortion in America

Abortion was first criminalized in the mid 1900s amidst concerns that too many white women were ending their pregnancies.

For years, it’s been getting harder for American women to access abortion services as clinics have closed and state laws have raised barriers to getting these procedures. In coming years, the Supreme Court may move closer to overturning Roe vs. Wade altogether.