Introduction

The history of these civilizations stretches from very ancient times to just a few centuries ago. Mayan civilization dates back to 2000 B.C.E. It reached its height in what is called the Classic period, from about 300 to 900 C.E. The Aztecs and the Incas built their empires in the two centuries before the Spanish arrived in the 1500s.

Scholars have learned about these cultures in various ways. They have studied artifacts found at the sites of old settlements. They have read accounts left by Spanish soldiers and priests. And they have observed traditions that can still be found among the descendants of the Mayas, Aztecs, and Incas.

The more we learn about these cultures, the more we can appreciate what was special about each of them. The Mayas, for example, made striking advances in writing, astronomy, and architecture. Both the Mayas and the Aztecs created highly accurate calendars. The Aztecs adapted earlier pyramid designs to build massive stone temples. The Incas showed great skill in engineering and in managing their huge empire. Moreover, those great cultures contributed to entertainment development, coming up with games that have evolved into football, card games like multiplayer solitaire, and other entertainment forms we enjoy daily.

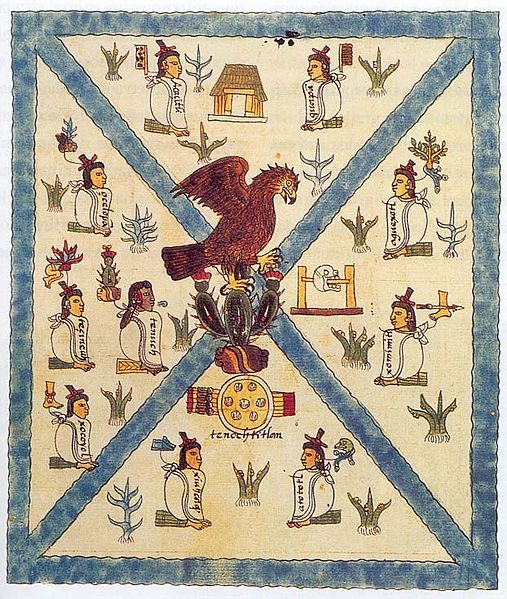

Aztecs

The Aztecs adapted many ideas from earlier groups, including their calendars and temple-pyramids. But the Aztecs improved on these ideas and made them their own.

Science and Technology

One of the Aztecs’ most remarkable technological achievements was the construction of their island city, Tenochtitlán. The Aztecs enlarged the area of the city by creating artificial islands called chinampas. Today, flower farmers in Xochimilco, near Mexico City, still use chinampas. Tourists enjoy taking boat trips to see these “floating gardens.”

Just as impressive as the chinampas were the three causeways that connected Tenochtitlán to the mainland. The causeways were often crowded with people traveling in and out of the capital. During the rainy season, when the waters of the lake rose, the causeways also served as dikes.

To manage time, the Aztecs adapted the Mayan solar and sacred calendars. The 365-day solar calendar was especially useful for farming, since it tracked the seasons. Priests used the sacred 260-day calendar to predict events and to determine “lucky” days for such things as planting crops and going to war.

One of the most famous Aztec artifacts is a calendar called the Sun Stone. Dedicated to the god of the sun, this beautifully carved stone is nearly twelve feet wide and weighs almost twenty-five tons. The center shows the face of the sun god. Today, the Sun Stone is a well-known symbol of Mexico.

Art and Architecture

The Aztecs practiced a number of arts, including poetry, music, dance, and sculpture. Poets wrote verses to sing the praises of the gods, to tell stories, and to celebrate the natural world. Poetry was highly valued. Aztec poets sung their poems or recited them to music. Sometimes, actors performed them, creating a dramatic show with dialogue and costumes.

Music and dance were important features of Aztec ceremonies and holidays. People dressed up for these special occasions. Women wore beautiful blouses over their skirts. Men painted their faces, greased their hair, and wore feathered headdresses. The dancers formed large circles and moved to the beat of drums and the sound of rattle bells. The dances had religious meaning, and the dancers had to perform every step correctly. Sometimes, thousands of people danced at one time. Even the emperor occasionally joined in.

The Aztecs were also gifted painters and sculptors. Painters used brilliant colors to create scenes showing gods and religious ceremonies. Sculptors fashioned stone statues and relief sculptures on temple walls. They also carved small, lifelike figures of people and animals from rock and semiprecious stones, such as jade. In technical craft and beauty, their work surpassed that of earlier Mesoamerican cultures.

In architecture, the Aztecs are best remembered today for their massive stone temples. The Aztecs were unique in building double stairways, like those of the Great Temple in Tenochtitlán. The staircases led to two temples, one for the sun god and one for the god of rain. Smaller pyramids nearby had their own temples, where sacrificial fires burned before huge statues of the gods.

Language and Writing

Spoken language was raised to an art in Aztec society. Almost any occasion called for dramatic and often flowery speeches. The rich vocabulary of the Aztec language, Nahuatl, allowed speakers to create new words and describe abstract concepts.

The Aztec system of writing used both glyphs and pictographs. A pictograph is a drawing that depicts a word, phrase, or name, rather than symbolizes it. For example, the Aztec pictograph for war was a symbol of a shield and a club. The Aztecs did not have enough pictographs and glyphs to express everything that could be spoken in their language. Instead, scribes used writing to list data or to outline events. Priests used these writings to spark their memories when relating stories from the past.

Inca

Like the Aztecs, the Incas often borrowed and improved upon ideas from other cultures. But the Incas faced a unique challenge in managing the largest empire in the Americas. Maintaining tight control over such a huge area was one of their most impressive accomplishments.

Science and Technology

The Incas’ greatest technological skill was engineering. The best example is their amazing system of roads.

The Incas built roads across the length and width of their empire. To create routes through steep mountain ranges, they carved staircases and gouged tunnels out of rock. They also built suspension bridges over rivers. Thick rope cables were anchored at stone towers on either side of the river. Two cables served as rails, while three others held a walkway.

In agriculture, the Incas showed their technological skill by vastly enlarging the system of terraces already in use by earlier Andean farmers. The Incas anchored their step-like terraces with stones and improved the drainage systems in the fields. On some terraces, they planted different crops at elevations where the plants would grow best.

To irrigate the crops, the Incas built canals that brought water to the top of a hillside of terraces. From there, the water ran down, level by level. People in South America still grow crops on Incan terraces.

The Incas also made remarkable advances in medicine. Incan priests, who were in charge of healing, practiced a type of surgery called trephination. Usually, the patient was an injured warrior. Priests cut into the patient’s skull to remove bone fragments that were pressing against the brain. As drastic as this sounds, many people survived the operation and recovered full health.

Walking Across Space: Incan Rope Bridges

You’re standing at the edge of a canyon high in the Andes Mountains, looking down at a raging river far below. You look across to the other side. The only way to get there is to walk across a narrow rope bridge. You grit your teeth and step out into space. The bridge sinks beneath your weight. Will the bridge hold? Will it flip you over into the gorge below? Don’t worry—this bridge was built by people who really know what they’re doing!

The Incas lived in a land of high mountains separated by rivers and deep valleys. They built a vast system of roads to help them travel and communicate. They also built amazing bridges that crossed the vast chasms between cliffs and canyons. These bridges were made of thick rope cables woven from grass. That’s right—grass.

For centuries, these rope bridges played a critical role in transportation throughout the Andes Mountains. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) professor John Ochsendorf is a structural engineer who has spent years studying Incan rope bridges. He thinks that the bridges were just as important as the Incan road system. They allowed the Incas to cross natural barriers, such as canyons and rivers. Without the amazing engineering that created these rope bridges, the Incas could not have connected the roads into the effective communication system that helped them create and control their large empire.

In the Quechua language, a grass rope bridge is called a Keshwa-chaka. According to Ochsendorf, there were two types of rope bridges: large and small. Each type was carefully planned and maintained. There is evidence that the Incan emperor himself drew plans for large bridges and made sure that they were repaired and protected.

Large bridges had a Chaka Camayoc, which means “bridgekeeper” in the Quechua language. Living at the bridge, the Chaka Camayoc was responsible for guarding and repairing it. Large bridges were usually located on the Royal Road, built between the present-day cities of Cuzco, Peru, and Quito, Ecuador.

Smaller bridges connected rural communities to one another and to the Royal Road. The local people were responsible for building and maintaining them as part of their annual service to the empire. Working together, they repaired or rebuilt these bridges every year.

The last remaining Incan rope bridge is believed to be located in the remote village of Huinchiri, Peru. It hangs about two hundred feet over the Apurimac River and spans a distance of over one hundred feet. People in the area use a modern metal bridge for everyday transportation across the river. But each year, Quechua villagers hold a three-day festival during which they cut down the old rope bridge and build a new one. Using weaving and construction techniques that have passed from generation to generation, they honor their culture and ancestors. Tourists come from around the world to watch the villagers rebuild the bridge.

During the festival, villagers organize the work in the same way it has been done for centuries. Each household is responsible for a certain job. There are four key tasks in constructing a bridge: making rope; braiding it into cables; repairing or rebuilding the stone anchors on either side of the river; and making the ties, the handrails, and a floor system.

The basic material that makes up the huge cables needed to hold up the bridge is a thin, two-ply rope. Hundreds of families work before the festival begins to make this rope. They start by gathering dry stalks of grass. Then they twist pieces of grass together. As they add grass, the rope becomes longer and longer. The villagers make the rope in lengths of about fifty yards. Approximately ten miles of rope are needed to build the bridge.

On the first day of the festival, construction begins. Families bring their handmade thin ropes to the bridge site. The chief bridge builder and the priest make offerings to Paca Mama, or Mother Earth. They ask that she bless their work. They also ask that the bridge stay safe and strong until they rebuild it next year.

Next, the men make large cables. They braid the thin ropes together, three at a time, to make thicker cables. Then they braid these cables together to make even thicker ones. Each cable measures 6 inches in diameter, weighs about 150 pounds, and is 150 feet long. Six of these big cables are needed to make the bridge. Four cables form the bridge floor to carry the weight of people and animals, and the remaining two cables serve as handrails.

On the second day, the villagers cut down the old bridge and let it fall into the river. Then the men put up new cables. A guide rope is attached to each cable. Using the guide rope, the men pull each cable across the river. They lift each one to the top of the cliff on the other side of the canyon. Then, they pull on the cables to make sure they are very tight. Finally, they connect the cables to strong timbers and stone anchor blocks located on each side of the river.

On the festival’s final day, people gather at the bridge in colorful party clothes. They watch the current bridgekeeper connect rope ties from the floor cables to the handrail cables. Other men lay down cross-ties, or sticks that will help keep the floor cables in place. Finally, they lay reed floor mats over the cross-ties and floor cables to complete the bridge.

Once the bridge is finished, a celebration begins. The villagers may offer guests or tourists a traditional Quechua meal. Then anyone who wants to is invited to walk across the bridge. Would you walk across it?

When Spanish soldiers first saw these bridges, they were terrified. Some soldiers crawled across them on their hands and knees. The bridges were strong and safe, however. The Spanish even crossed them with their horses and cannons.

Ephraim George Squier, an American visitor to Peru in the 1870s, gave good advice about crossing the rope bridge over the Apurimac. He wrote, “It is usual for the traveler to time his day’s journey so as to reach the bridge in the morning, before the strong wind sets in; for, during the greater part of the day, it sweeps up the canyon of the Apurimac with great force, and then the bridge sways like a gigantic hammock, and crossing is next to impossible.”

An American scientist who crossed the newly rebuilt bridge described her walk with words that echoed those of Ephraim Squier from the 1870s. As she crossed slowly to keep the bridge from swaying too much or flipping over, she said, “I want to look down, but I’m afraid to look down, so I’m looking at everybody across. I know I can do this. I think I’m going to be sick. No, I’m not.”

Many tourists accept the invitation to walk across the newly finished bridge. After watching its construction, they feel sure that it is sturdy and safe. Laboratory tests done by Professor John Ochsendorf show that the bridge is quite strong. It can hold 56 people spread out in a row across the bridge at one time, or 4,200 pounds of weight.

What the Incas accomplished centuries ago makes their Quechua descendants very proud. They know that their ancestors were gifted engineers. The Incas solved the problem of connecting roads by using the resources at hand. They also know that these bridges function well, since they were rebuilt again and again for more than 400 years, until metal bridges started to replace them in the 19th century. Anyone watching the Incas’ Quechua descendents build a bridge in just three days will see that they are living examples of a way of life that has endured for centuries.

Art and Architecture

Making textiles for clothing was one of the most important Incan arts. The quality and design of a person’s clothes were a sign of status. The delicate cloth worn by Incan nobles often featured bright colors and bold geometric patterns. Incan women also made feather tunics, or long shirts, weaving feathers from jungle birds right into the cloth.

Fashioning objects out of gold was another important art. The Incas prized gold, which they called the “sweat of the sun.” Gold covered almost every inch inside the Temple of the Sun in the Incan capital city of Cuzco. Incan goldsmiths also fashioned masks, sculptures, knives, and jewelry.

Music was a major part of Incan life. The Incas played flutes, seashell horns, rattles, drums, and panpipes. Scholars believe that the modern music of the Andes region preserves elements of Incan music.

In architecture, the Incas are known for their huge, durable stone buildings. The massive stones of Incan structures fit together so tightly that a knife blade could not be slipped between them. Incan buildings were sturdy, too—many remain standing today.

Language and Writing

The Incas made their language, Quechua (KECH-wah), the official language of the empire. As a result, Quechua spread far and wide. About ten million people in South America still speak it.

The Incas did not have a written language. Instead, they developed an ingenious substitute: the knotted sets of strings called quipus. The Incas used quipus as memory aids when sending messages and recording information.

Maya

Many of the greatest achievements of the Mayas date from the Classic period (about 300 to 900 C.E.). Hundreds of years later, their ideas and practices continued to influence other Mesoamerican groups, including the Aztecs.

Science and Technology

The Mayas made important breakthroughs in astronomy and mathematics. Throughout Mayan lands, priests studied the sky from observatories. They were able to track the movements of stars and planets with great accuracy. The Mayas used their observations to calculate the solar year. The Mayan figure for their year of 365.2420 days is amazingly precise.

These calculations allowed the Mayas to create their solar calendar of 365 days. They also had a sacred 260-day calendar. Every 52 years, the first date in both calendars fell on the same day. This gave the Mayas a longer unit of time that they called a Calendar Round. For the ancient Mayas, this 52-year period was something like what a century is to us.

Mayan astronomy and calendar-making depended on a deep understanding of mathematics. In some ways, the Mayan number system was like ours. The Mayas used place values for numbers, just as we do. However, instead of being based on the number 10, their system was based on 20. So instead of place values for 1s, 10s, and 100s, the Mayas had place values for 1s, 20s, 400s (20 times 20), and so on.

The Mayas also recognized the need for zero—a discovery made by few other early civilizations. In the Mayan system for writing numbers, a dot stood for one, a bar for five, and a shell symbol for zero. To add and subtract, people lined up two numbers and then combined or took away dots and bars.

Art and Architecture

The Mayas were equally gifted in the arts. They painted, using colors mixed from minerals and plants. We can see the artistry of Mayan painters in the Bonampak murals, which were found in Chiapas, Mexico. The murals show nobles and priests, as well as battle scenes, ceremonies, and sacrifice rituals.

The Mayas also constructed upright stone slabs called steles (STEE-leez), which they often placed in front of temples. Most steles stood between 5 and 12 feet tall, although some rose as high as 30 feet. Steles usually had three-dimensional carvings of gods and rulers. Sometimes, the Mayas inscribed them with dates and hieroglyphics in honor of significant events.

Another important art was weaving. We know from steles and paintings that the Mayas wove colorful fabric in complex patterns. Women made embroidered tunics called huipiles and fashioned lengths of cloth for trade. Mayan women still use similar techniques today. They still make their huipiles in traditional designs. People from different towns can be distinguished by the colors and patterns of their garments.

In architecture, the Mayas built temple-pyramids from hand-cut limestone bricks. An unusual feature of Mayan buildings was a type of arch called a corbel vault. Builders stacked stones so that they gradually angled in toward each other to form a triangular archway. At the top of the arch, where the stones almost touched, one stone joined the two sides. The archway always had nine stone layers, representing the nine layers of the underworld (the place where souls were thought to go after death).

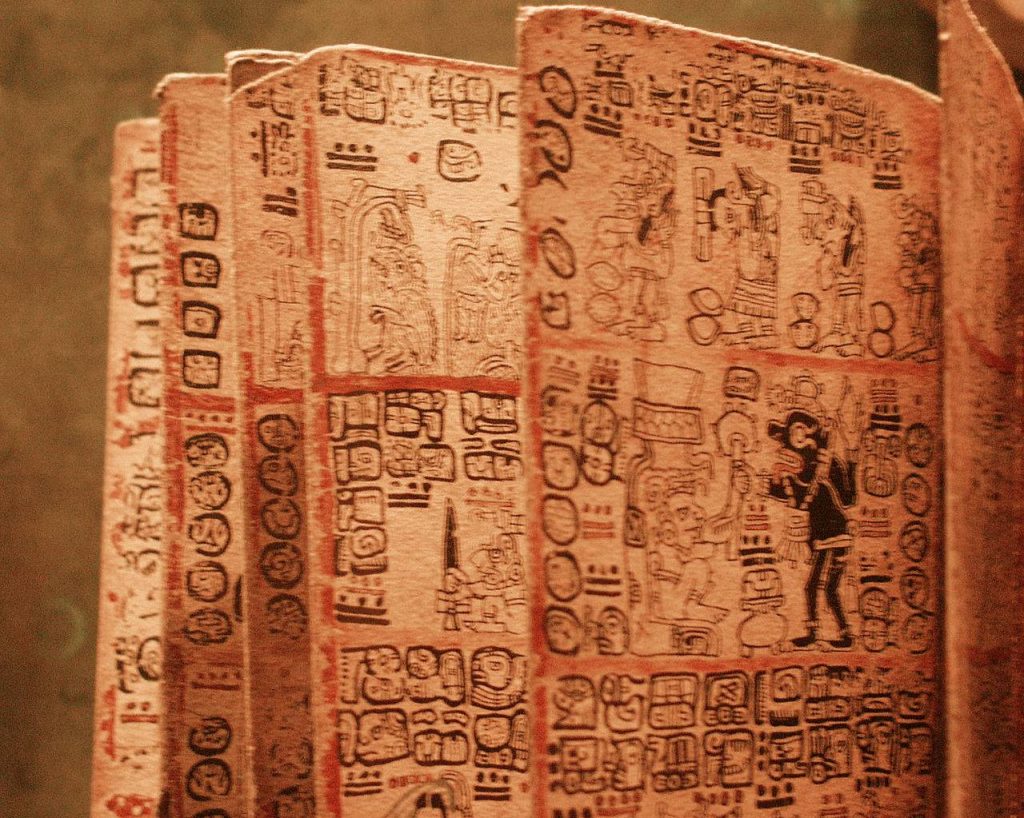

Language and Writing

The Mayas developed the most complex system of writing in the ancient Americas. They used hieroglyphics, or picture symbols, to represent sounds, words, and ideas. Hieroglyphic inscriptions have been found on stoneware and other artifacts dating from possibly as early as 300 B.C.E.

Over time, the Mayas created hundreds of glyphs. Eventually, scribes could write down anything in the spoken language. They often wrote about rulers, history, myths and gods, and astronomy.

Not all Mayan groups shared the same language. Instead, they spoke related dialects. Today, about four million Mesoamericans still speak one of thirty or so Mayan dialects.

Originally published by Flores World History, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.