Vespasian’s efforts to revive official cult honors for the deified Claudius for continuity.

By Dr. Andrew Gallia

Professor of History

University of Minnesota

(De)Constructing Nero’s Legacy

In the second epigram of the De Spectaculis, Martial gives a tour of the area surrounding Rome’s new amphitheatre that is specifically crafted to highlight the contrast between the urban policies of the Flavian dynasty and those of Nero, whose infamous Golden House once occupied that quarter of the city. As Kathleen Coleman explains in her commentary, ‘Our poem is like a palimpsest: it supplies a map of the contemporary area, but at the same time we see traces of the same district under Nero.’1 This polemically loaded process of chronological displacement can be traced throughout the poem, from the sidereus colossus (‘starry colossus’, 1), which has taken the place of the invidiosa feri […] atria regis (‘hated halls of a cruel king’, 3), to the amphitheatre itself, which rises on the site of the former stagna Neronis (‘pools of Nero’, 5–6), to the new thermas (‘baths’, 7), which mark a spot where housing had been arrogantly expropriated to the imperial estates, and ultimately to the shade of the Claudia […] porticus (‘ Claudian […] portico’, 9), used to establish the furthest extent of Nero’s abolished palace.2 This sequence of retrospective antitheses, keyed to the repeated phrase hic ubi, or simply ubi, is meant to condemn Nero’s building programme as much as it praises the new edifices of the Flavians. The message, which Martial proclaims at the end of the poem, is reddita Roma sibi est et sunt […] / deliciae populi, quae fuerant domini (‘Rome has been returned to itself and […] what had been the pleasures of a master are now the pleasures of the people’, 11–12).3

And yet, from the very first line, we encounter a problem with the dichotomy Martial claims to be mapping out between the two regimes. As it happened, the colossus described as standing along the route of the Sacra Via was not originally intended as a Flavian monument. We know from Pliny the Elder (HN 34.45, cf. Suet. Ner. 31.1) that this work of the sculptor Zenodorus was originally commissioned as a statue of Nero, but was completed after that emperor’s death and condemnation as a dedication to the sun.4 The redesign of the statue and the demolition of the surrounding vestibule of the Golden House would have changed the interpretative context somewhat, but as Anne Wolsfeld elucidates in greater detail below, this monument cannot be used to establish a straightforward division between the restored Rome of the Flavians and its Neronian counterpart.5

The divergence between the actual history of this monument and the significance that Martial attempts to impose upon it reveals that, even in its earliest phases, the nature of the Flavian response to Nero (or in this case Nero’s Rome) was never one of absolute binary opposition, in which the Flavians simply tore down whatever their predecessor had done and proceeded to do the opposite. This would seem to be an obvious point, for however bad an emperor Nero may have been, and however much worse his successors made him out to be, there inevitably would have been some things worth keeping, such that the Flavians would have to be clever – and occasionally bend the truth a little – in squaring the continuation of advantageous policies within an overarching narrative of salvation from the horrors of Nero’s tyranny. The corollary but somewhat less obvious point is that the logic of being against Nero did not in itself necessarily underpin apparent shifts away from Neronian precedents. If we want to understand the policies of the Flavian regime, therefore, we must interpret their aims in broader terms than the mere desire to set themselves apart from the last of the Julio-Claudians.

The topic with which I will attempt to bring this issue into focus in this chapter relates to the last item in Martial’s list of supposedly ‘Flavian’ monuments, the ‘Claudian portico’ that stood around the Temple of Divus Claudius on the Caelian Hill. The completion of Claudius’ temple and its porticoes, which Martial indicates stood at the southern boundary of the demolished palace complex, is generally recognized as one of the major building projects with which Vespasian sought to set himself apart from the priorities of his decadent predecessor.6 Because of its religious and dynastic implications, the restoration of the temple and of Claudius’ cult generally represents a more complex and potentially self-contradictory aspect of the response to Nero’s legacy than the ‘rhetorical sleight of hand’ with which Martial and the Flavians attempted to expropriate credit for other Neronian works.7 Beyond the apparent contrast with Nero’s fecklessness, sufficient explanation for this undertaking has not yet been offered.

We know that Vespasian was adept in his selection and manipulation of earlier precedents, and that he had frequent recourse to the example of Augustus in particular in establishing a new dynasty for himself and his sons, all the while denigrating Nero’s memory.8 In this case, however, why did he choose to reaffirm, and even actively promote, the divinity of Nero’s adoptive father? Such a course of action appears counter-intuitive and perhaps even risky in hindsight. For many years, Nero’s position had been linked with that of Claudius. Although these ties began to break down in the latter part of Nero’s reign, the Flavian rejection of Nero need not have led to an affirmative celebration of Divus Claudius. The accounts of Tacitus and Suetonius testify to the mixed legacy of Claudius’ reign as well as the hostility with which a significant portion of the elite continued to regard his memory.9 The new emperor therefore needed a more compelling reason to countermand the judgement passed on Claudius’ divinity by Seneca in the Apocolocyntosis than the fact that Nero was also thought to have impiously rejected his father’s cult. It is the purpose of this chapter, therefore, to reopen the question of the place of Divus Claudius within the broader ideological programme of the Flavian regime.

Templum Divi Claudii

We can begin with the temple. Its status as a Flavian monument is affirmed by Suetonius, who says that the project was begun by Agrippina the Younger, but cancelled by Nero (presumably following his mother’s murder) when the structure was torn down, even to its very foundations (Vesp. 9.1, cf. Claud. 45). Our ability to check this final claim against the archaeology of the temple’s remains has not advanced much since the publication of Colini’s study of the topography of the Caelian Hill.10 It was already clear then, however, that the eastern facade of the temple platform was Neronian in date. This wall, still visible along the modern Via Claudia, was ornamented with a series of niches containing sculptures and fountains. Water was supplied to this nymphaeum through a spur off of the Aqua Claudia, also constructed under Nero (as discussed by Frontinus, Aq. 2 .76).11 The preservation of these features points to some degree of continuity between Nero’s designs for this area of the city and the f inal form of the temple as it was completed by the Flavians.12

The current state of the archaeological evidence makes it impossible to assess the full extent of this continuity, but it must also be conceded that Suetonius’ claims about Nero demolishing the temple would have made little sense if there had not at least been a significant change in the direction of the construction work carried out on the Caelian. The nature and purpose of these changes is inevitably intertwined with the chaotic dynastic politics of Nero’s reign, which further complicate our source tradition. Suetonius’ attribution of the temple’s initial phase of construction to Agrippina appears to be supported by recent excavations on the western side of the hill that point to two phases of construction under Nero, which would be consistent with an alteration to the plan following Agrippina’s death.13

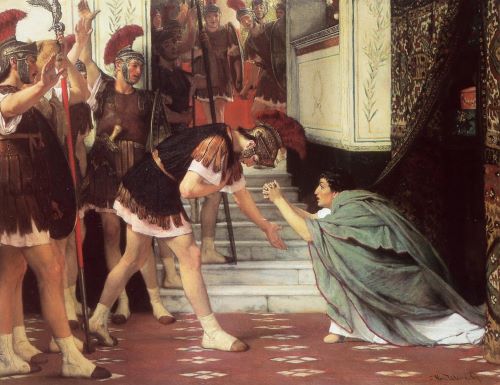

In the Tacitean account of Claudius’ apotheosis, the historian emphasizes Agrippina’s deliberate imitation of Livia, whose exalted position she sought to rival (Ann. 12.69.3). One of the honours Agrippina received from the Senate was therefore to be made a priestess of her deified husband, just as Livia had been for Divus Augustus (Tac. Ann. 13.2.3, cf. Cass. Dio 56.46.1). This evidence is taken more or less at face value by Anthony Barrett, who regards Claudius’ deification as ‘an important personal triumph for Agrippina’, and in some ways a validation of policies she had had a hand in shaping during her time as empress.14

While there is no reason to doubt the essential truth of these accounts, I suspect that Agrippina’s role in securing Claudius’ divinity may also have been played up by Nero and his allies following her death. Agrippina’s unprecedented power under Claudius and as dowager empress in the early years of Nero’s reign, to which the deaths of prominent figures like Lollia Paulina and Statilius Taurus (under Claudius) and M. Iunius Silanus (in the first year of Nero’s reign) could be attributed, proved useful in establishing a rationale for her murder.15 As Nero abandoned the construction of the temple and moved away from his own stake in Claudius’ divinity, the producers of this hostile tradition would have been able to further impugn Agrippina’s memory by highlighting the perversity of her attempt to gain personal glory through the deification of a husband whose murder she was also thought to have arranged (Cass. Dio 60.35.2, cf. Tac. Ann. 12.66–67, Plin. HN 2 2 .9 2).16

Certainly Agrippina’s connection with the worship of Divus Claudius cannot have had anything to do with Vespasian’s decision to complete the temple. If what Suetonius says about Vespasian being in danger during the early years of Nero’s reign because of Agrippina’s hostility toward the friends of Narcissus (Vesp. 4.2) is true, there would have been little incentive for him to honour his persecutor by completing a project that she had begun.17 More importantly, as Annemarie Ambühl explains in another chapter of this volume, Agrippina’s legacy as a preeminent figure within the imperial household (itself a reflection of Livia’s unprecedented position under Augustus and Tiberius) was a legacy of the Julio-Claudian sexual politics that the Flavians (at least Vespasian and Titus) purposefully eschewed in their response to Nero’s principate.

Agrippina’s role in this narrative is ultimately incidental to the problem we must confront in trying to understand why the Flavians chose to revive the cult of Divus Claudius, however. The rationale behind Claudius’ deification had not simply been to glorify Agrippina as the widow of a deified emperor; it was also, no doubt more recognizably, about establishing Nero as the son of one.18 Like Livia before her, Agrippina played an important role in creating this link between father and adoptive son, but the person whose position and authority were ultimately best served by Claudius’ divinity was Nero himself.

Nero as ‘Divi Filius’

Imperial titulature announces Nero as the son of Divus Claudius, a claim to charismatic authority with solid roots in the precedents established by Octavian and Tiberius.19 At some point, however, Nero lost interest in tying his own image to that of his adoptive father. Unlike Tiberius, who continued to style himself as the son of a god throughout his reign, Nero dropped the words divi filius from his titles on the imperial coinage within a few years of Agrippina’s death.20 Suetonius (Ner. 33.1) states that Nero was openly hostile to Claudius’ memory, joking that he had ceased ‘to play the fool’ among mortals (punning on a mispronunciation of mŏrari, ‘to linger’) and overturning his decrees and legal rulings. The biographer does not say anything explicit about abolishing the cult, however, although his comment that Nero enclosed the site of Claudius’ funeral pyre (and thus his apotheosis) with nothing but a flimsy earthen wall suggests a measure of disrespect, if not total disregard, for his divinity.21 The supposed demolition of the Caelian temple would be consistent with this position, as would the toleration of such explicitly hostile assessments of Claudius’ divinity as those found in the Apocolocyntosis or Junius Gallio’s remark that Claudius had been hauled up into heaven by a hook (Dio [Xiph.] 60.35.2–4).22 As I have already suggested, Agrippina’s close association with Divus Claudius may have been used to paint her as insincere and power-hungry following her murder, a line of attack that could be pursued more effectively as the emperor distanced himself from the cult.

Insofar as these attitudes coalesced into anything resembling a formal policy of denigration, the marginalization of Claudius’ divinity under Nero was slow to take form and was never systematically enacted. The inscriptions of the Arval Brethren securely document sacrifices offered to Divus Claudius at the start of the year 60 (CIL 6.2042 = CFA 28de) and again after Otho became emperor in January of 69 (CIL 6.2051 = CFA 4 0), but these records are too fragmentary to say whether or for how long the practice continued during the interval between these dates.23 In 61, two years after the assassination of Agrippina, Tacitus (Ann. 14.31.4) records that the cult was still going strong in Britain, as the extractions used to fund the Temple of Divus Claudius in Colchester became a catalyst for the rebellion of Boudicca.24 Combined with the continued prevalence of references to divine paternity elsewhere in the epigraphic record, this evidence suggests that no move was made to abandon the cult until after Nero’s divorce from Octavia in 62, at which point Nero’s break with the Claudian legacy was complete.25

Although Nero’s status as divi filius had disappeared from coins emanating from the imperial mint, Divus Claudius nevertheless continued to appear on the local coinages of Cappadocia and Syria until late in the reign.26 Nero’s status as the son of the deified emperor also continues to turn up in inscriptions set up outside of Rome after 62.27 Perhaps the most interesting case is a double statue base from the town of Luna in Campania, which dates to 67 (CIL 11.1331 = ILS 233). The first dedication begins with Nero’s full titles:

Imp. Neroni Claudio divi Claudi f. Germ.

Caesaris n. Ti. Caesaris Aug. pron. divi Aug. abn.

Caesari Aug. Germ. p. m. tr. pot. XIII imp. XI cos. IIIIFor Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, son of Divine Claudius, grandson of Germanicus Caesar, great-grandson of Tiberius Caesar Augustus, great-great-grandson of Divine Augustus, pontifex maximus, with tribunician power for the thirteenth time, imperator eleven times, consul four times.28

The companion inscription is headed:

Divae Poppaeae Augustae

Imp. Neronis Caesaris August(i)For Divine Poppaea Augusta, wife of Emperor Nero Caesar Augustus.

Beneath each of these titles, identical texts in a smaller script identify the sponsor of these dedications as L. Titinius Glaucus Lucretianus, whose full cursus honorum as an equestrian administrator is provided, along with an explanation that the monument was erected ex voto suscepto pro salute Imp. Neronis (‘from a vow undertaken for the well-being of Emperor Nero’) which had been pledged in 65, while Glaucus was still serving as praefectus pro legatus in the Balearic islands.29

Titinius Glaucus elsewhere credits Divus Claudius with involvement in his elevation to the duumvirate (CIL 11.6955 = ILS 8902: primus creatus bene/ficio divi Claudii), so it is plausible that some measure of personal devotion lies behind his continued invocation of Claudius’ divinity so long after its obsolescence at Nero’s court. It must also be noted, however, that this devotion does not portend any alienation from the current emperor. Glaucus’ career as a mid-level imperial functionary had continued to advance to new heights under Nero even after the elimination of Agrippina and Octavia. As a local priest of the imperial cult, flam(en) Romae / et Aug(ustorum?), Glaucus is likely to have been well informed on current policy regarding the divinity of Nero’s closest kin. Such awareness is confirmed by the decision to commemorate the deification of Poppaea, which took place in the same year as the original vow for the emperor’s safety (Tac. Ann. 16.6.1, cf. 16.21.2). Whether this vow was prompted by the apotheosis of Poppaea itself or a need to advertise loyalty in the aftermath of the Pisonian conspiracy is unclear (although the two issues were not unrelated: see Tac. Ann. 16. 22 .3).30 However one looks at it, the inclusion of the formula divi Claudi filio in Nero’s titulature can only be interpreted as a gesture of respect intended to bolster the emperor’s claim to charismatic auctoritas. Whether it would have been received as such does not really matter – this is the ideological work that the emperor’s subjects thought Claudius’ divinity was supposed to do for Nero.

Divinization and ‘Faith’

Glaucus’ case is instructive, because one of the primary arguments regularly given for the renewed emphasis on Claudius’ divinity under the Flavians is that Vespasian, whose rise to power began with a posting as legionary legate during the conquest of Britain (where he earned triumphal insignia: Suet. Vesp. 4.1–2), felt a personal affinity for his former commander-in-chief.31 This may well have been the case, although it is worth remembering that Josephus’ account of those early campaigns emphasizes the unearned glory that Claudius obtained through Vespasian’s hard work (καὶ τῷ πατρὶ Κλαυδίῳ παρέσχε χωρὶς ἱδρῶτος ἰδίου θρίαμβον καταγαγεῖν, ‘he permitted his [sc. Nero’s] father Claudius to celebrate a triumph without sweat of his own’, BJ 3.5). More to the point, the careers of the Flavians had advanced under Nero as well (and far more spectacularly than Glaucus), yet we do not expect Vespasian to show gratitude for the imperial favour he had received under Nero.32

Whatever credence one might give to stories about Vespasian nodding off at Nero’s recitals (Suet. Vesp. 4.4, Tac. Ann. 16.5.3), attempting to divine the sincerity of private, affective motivations is not a very useful, let alone reliable, way to explain an emperor’s treatment of his predecessors. This is not to say that sincerity of feeling is irrelevant to the question of an emperor’s posthumous divinity, however. While Christianizing notions of ‘faith’ are best avoided in discussions of the imperial cult, Pliny does emphasize the importance of personal belief when discussing the deif ication of Nerva in the Panegyricus.33 Specifically, he contrasts Trajan’s motivations with those of previous emperors in these terms:

Dicavit caelo Tiberius Augustum, sed ut maiestatis crimen induceret; Claudium Nero, sed ut irrideret; Vespasianum Titus, Domitianus Titum, sed ille ut dei f ilius, hic ut frater videretur. Tu sideribus patrem intulisti non ad metum civium, non in contumeliam numinum, non in honorem tuum, sed quia deum credis.

Tiberius declared that Augustus was divine, but in order to justify charges of treason. Nero did this with Claudius, but in order to mock him; Titus did this with Vespasian, and Domitian Titus, but one in order to appear as the son of a god, the other as the brother of one. You raised your father to the stars not to terrorize citizens, nor in contempt for the divine, nor for your own honour, but because you believe him to be a god. (Plin. Pan. 1 1 . 1– 2)

For this discussion, the cynical rationales that Pliny ascribes to earlier rulers are just as important as his claims about Trajan’s motivation for deifying Nerva. Presaging sentiments that f ind fuller articulation in the early books of Tacitus’ Annales (1.73, 4.34), Pliny accuses Tiberius of using Augustus’ divinity as a pretext for launching accusations under the maiestatis crimen against those who insulted the divinity of his predecessor.34 He then conf lates the gist of the Apocolocyntosis with the early policy of Nero’s reign, saying that Nero only deified Claudius in order to mock him. Finally, he attacks the Flavians for doing what modern historians still typically assume emperors were up to in deifying their predecessors, which is to say basking in the reflected glory of a divine father, or in Domitian’s case with Titus, a brother.35

At the end of this unsettling list of dubious motivations, Pliny comes to Trajan, whom he claims had no other motive than the sincere conviction that Nerva was a god. It must be conceded that none of Pliny’s explanations can f it what Vespasian was doing in restoring the honour of Divus Claudius except, perhaps, this last one. Seeing as how Trajan also acquired a measure of personal glory through the deification of Nerva (and later his natal father as well), it seems that we should move beyond the question of belief, which even if sincere could still be deployed as ideological cover for other aims.36 The problem persists, therefore. If anything, Pliny’s claim that Nero’s deification of Claudius had been an act of ridicule makes Vespasian’s policy more difficult to understand. Why decide to take seriously what had come to be regarded as an impious joke?

Claudius as ‘Exemplum’: Emperor and ‘Divus’

A somewhat more promising way of framing the previous argument is suggested by the so-called lex de imperio Vespasiani, the monumental inscription that preserves the latter part of a lex satura through which Vespasian was formally vested with power following the capture of Rome by Flavian armies in late December of 69 (CIL 6.930 = ILS 2 4 4).37 As is well known, this law is arranged into a series of clauses that enumerate the particular powers and prerogatives granted en bloc to the new princeps at the time of his accession. Most of these clauses also provide specific reference to the individual emperors to whom similar authority had previously been granted, namely Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius. As we should expect, Nero is not mentioned among these precedents, and neither is Caligula.38 Among the trio of acknowledged imperial predecessors, Claudius is the only one to be cited individually, when in the fifth clause of the surviving tablet (lines 14–16) he is invoked as a precedent for expanding Rome’s pomerium, a privilege Vespasian would ultimately avail himself of in 75 (CIL 6.31538a-c = ILS 248, cf. CIL 6.1231a-c = ILS 213, Tac. Ann. 12.23.2).39 Like the censorship that Vespasian and Titus held in 73, this was one of several Claudian innovations revived by the Flavians, which point to his importance as a model for the new regime as they went about asserting their position at the top of the Roman social order.40 This exemplary status might also have had something to do with the deference shown to Claudius’ divinity, but it cannot in itself explain the policy.

Before we can account for the relationship between Claudius’ divinity and his role as a precedent in the Flavian ideology of governance, there is some longstanding confusion about the way he is described in this law that needs to be cleared up. As a number of scholars going back to Charlesworth have pointed out, Claudius is not described with the epithet divus in the lex de imperio Vespasiani, despite the fact that Augustus is consistently described in these terms.41 This has been taken either as evidence for senatorial opposition to the notion of Claudius’ divinity at the start of Vespasian’s reign, or as a sign of initial uncertainty and/or ambivalence on the part of the Flavians regarding their plans to renew the cult. While I do not want to diminish the extent to which there were elements in the Senate hostile to both the memory of Claudius and the idea of his worship, this inscription cannot be used as proof of these senators’ inf luence at the time of Vespasian’s accession or, for that matter, as any kind of statement about the status of Claudius’ divinity at this crucial juncture.

Comparison with Flavian municipal legislation suggests that the omission of the title divus in this context is less significant than has sometimes been imagined. Throughout the tabula Irnitana, our most extensive example of these laws, we find the same collocation of Divus Augustus with (the non-divine) Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus, generally in limiting clauses that prohibit officials from acting contrary to the laws of the Roman people, senatus consulta, and the edicts, decrees, and decisions of previous emperors.42 What is remarkable about these legal texts is not the omission of divus from the titulature of Claudius, but rather its absence in the names of Vespasian and Titus.43 As we have them, these laws were promulgated under Domitian, and it is impossible to imagine that the emperor who dedicated not only a temple of Vespasian and Titus on the Capitol, but also the Templum Divorum in the Campus Martius and the Templum Gentis Flaviae on the Quirinal meant to leave any doubt about the divine status of his father and brother.44 In fact, he did not, for whenever these laws specify that someone should swear an oath, he is required to do so not just by Jupiter, but by Divus Augustus, Divus Claudius, Divus Vespasianus, and Divus Titus, as well as the genius of Domitian himself.45

At this stage in the development of Roman ideas about deified emperors, therefore, it appears that legal formulations were essentially consistent with patterns observed in literary texts, for example, those of Tacitus, in which Claudius is only described as divus twice: when discussing the invasion of Britain in the Agricola (13.3) and when explicitly referring to the operation of his cult in the Annales (14.31.4; cf. 12.65.3, 13.5.1).46 The deeds of Claudius’ principate were sometimes retroactively associated with his posthumously acknowledged divinity (cf. CIL 6.1257–1258 = ILS 218), but there was nothing pointed about the omission of the title in a non-religious context. In contrast to the extraordinary case of Augustus, whose divinity was invested with so much force that it regularly inserted itself into discussions of the accomplishments of his lifetime, for Claudius, as for Vespasian and Titus, there was a conceptual as well as a legal difference between the princeps, whose position other mortals might seek to attain, and the divus, whose nature and ideological function was of a substantially different order.47 While posthumous divinity might have been regarded as a consequence of virtuous rule (e.g. Plin. HN 2.18–19), it was not a prerequisite for inclusion among the canon of imperial predecessors upon whom the Flavians grounded their authority. This is why Tiberius was also invoked as a precedent in the lex de imperio Vespasiani and again in the tabula Irnitana (along with Galba), despite the fact that he had never been consecrated.48

The importance of this distinction between an emperor’s mortal acta and his posthumous divinity becomes even more pronounced when we consider the decidedly ambivalent legacy of Claudius as princeps. This Claudius represented as much a negative exemplum of what to avoid as a positive model for imitation.49 Although the Flavians embraced Claudius as a useful precedent for their assertions of imperial power, they generally distanced themselves from the most obvious mistakes of Claudius’ reign. Such unpopular features as his overinvolvement in the courts (Sen. Apocol. 7.4–5, Tac. Ann. 13.4.2), his reliance on freedmen in high-ranking posts (Sen. Apocol. 13.2–3; Plin. HN 33.134–135, 36.60), and especially the prominence granted to his wives (Plin. HN 35.201, Philostr. VA 5.32.2) were notably absent from Vespasian’s reign.50 Once we acknowledge that the Flavians’ invocation of Claudius as a source of authority was necessarily partial and selective, it also becomes clear that their interest in the divinity of Claudius needs to be understood on its own terms, rather than as part of a wholesale programme of Claudian restoration.

Divus Claudius and the Imperial Cult

To go further, I propose that the restoration of the temple and cult of the divine Claudius was ultimately motivated less by any perception of that emperor’s individual merit than by the importance of the category to which he belonged. As one of only three deified Caesars and the only one who was not a member of the gens Iulia, Divus Claudius provided above all else an important precedent for the eventual apotheosis of members of the Flavian dynasty. To put this in terms that Pliny might have used, Vespasian honoured the deified Claudius so that he too might become a god. The prospect of deification would have been of obvious importance as a source of charismatic authority for the Flavians, who lacked the prestige of familial nobilitas enjoyed by the Julio-Claudians and Nero in particular.51 The expansion and elaboration of the imperial cult in the provinces continued under Vespasian in sites ranging from Baetica to Gallia Narbonensis to Africa Proconsularis to Lycia.52 The trajectory led to apotheosis for Vespasian, and the eventual proliferation of cult activity surrounding the emperor and his family witnessed during the reign of Domitian.53 The restoration of Claudius’ cult and temple in Rome marked a renewed commitment to the importance of emperor worship, both as an institutional safeguard for the stability of the empire as a whole and as a source of inherent authority for the emperor himself.54

Scholars have come to think of posthumous deification as a routine feature of the transmission of imperial power from one ruler to the next.55 In this manner we adopt the perspective of the third-century historian Herodian, who prefaced his account of the apotheosis of Septimius Severus with the statement ἔθος γάρ ἐστι Ῥωμαίοις (‘it is a custom among the Romans’, 4.2.1, cf. App. B Civ. 2.148). As a matter of fact, however, this tradition was only really institutionalized under the Flavians.56 Of the five Julio-Claudian emperors, only Augustus and Claudius were deified, and, as we have already seen, serious doubts about the status of Claudius’ divinity had been raised before the end of Nero’s reign. The ‘long year’ 68–69 introduced three additional occupants of the imperial office, but all of these remained mortal to posterity. At the time of Vespasian’s accession, therefore, it was by no means inevitable that the imperial cult would take the form it did over the course of the next century and a half, with the imperial divi worshipped alongside the numen and/or genius of the living emperor, and forming what in hindsight might be regarded as a kind of ‘canon’ of meritorious rulers.57 The apotheosis of Vespasian provides the critical link for establishing this chain, and it in turn rested upon the precedent provided by Nero’s father, Claudius.

Last Words

Like Claudius’ apotheosis, the deification of Vespasian presents a number of challenges to the modern interpreter.58 One with particular relevance for the present discussion is the meaning of Vespasian’s deathbed pronouncement, vae, […] puto deus f io (‘Alas, […] I think I am becoming a god’, Suet. Vesp. 23.4, Dio [Xiph.] 66.17.3), which appears to confirm his plans for posthumous divinization.59 Manfred Schmidt has called attention to the echo of the final words ascribed to Claudius in the Apocolocyntosis: vae me, puto, concacavi me (‘Alas, I think I crapped myself,’ 4.3, cf. Tac. Ann. 1 2 .67.1).60 In light of what Suetonius reveals about the disease that led to Vespasian’s demise (Vesp. 24, cf. Dio [Xiph.] 66.17.1), the allusion can be read as a form of gallows humour about diarrhoea, which of course represented one of the leading causes of death in premodern Europe (as it remains today in places without access to clean drinking water and advanced medicines).61 The scatological register of this joke is in keeping with the biographer’s observations about Vespasian’s sense of humour, which Suetonius describes as etsi scurrilis et sordidae, ut ne praetextatis quidem verbis abstineret (‘sometimes clownish and dirty, since he did not even refrain from lewd words’, Vesp. 22). Schmidt nevertheless argues that the statement was spuriously attributed to the dying emperor by someone who wished to disparage Vespasian’s apotheosis by connecting it with Seneca’s mockery of Claudius’ divinity. But perhaps we should not be so suspicious of a self-deprecating joke.62 If Vespasian’s statement can be accepted as authentic, it offers a remarkably clear-sighted expression of the point I have attempted to articulate in this chapter, revealing that it was possible to embrace Claudius’ importance as a model for imperial apotheosis while simultaneously acknowledging even the most execratory elements of the anti-Claudian tradition. In so doing, Vespasian and his sons managed to preserve and transform the complicated legacy of Nero’s divine stepfather.63

Appendix

Endnotes

- Coleman (2006) 19.

- Hic ubi sidereus propius videt astra colossuset crescunt media pegmata celsa via,invidiosa feri radiabant atria regis unaque iam tota stabat in urbe domus. hic ubi conspicui venerabilis Amphitheatri erigitur moles, stagna Neronis erant. hic ubi miramur velocia munera thermas, abstulerat miseris tecta superbus ager. Claudia dif fusas ubi porticus explicat umbras, ultima pars aulae def icientis erat. reddita Roma sibi est et sunt te praeside, Caesar, deliciae populi, quae fuerant domini.‘Here, where the starry colossus sees the constellations close at hand and a lofty framework rises in the middle of the road, the hated halls of a cruel king used to gleam, and in the whole city there was only one house standing. Here, where the awesome bulk of the amphitheatre soars before our eyes, once lay Nero’s pools. Here, where we marvel at the swift blessing of the baths, an arrogant estate had robbed the poor of their dwellings. Where the Claudian portico weaves its spreading shade marks the point at which the palace finally stopped. Rome has been restored to herself, and with you in charge, Caesar, what used to be the pleasure of a master is now the pleasure of the people’ (Mart. Spect. 2, trans. Coleman).

- Charlesworth (1937) 54–55; Ramage (1983) 213; Ripoll (1999) 144–148; Darwall-Smith (1996) 36–38; Gallia (2016) 154–155; cf. Moormann (2003) 387 and in this volume.

- Albertson (2001), also La Rocca (2017) 197–201 and Varner (2017) 255.

- This objection does not necessarily apply to the amphitheatre itself, which may be regarded as a distinctly Flavian idea – or, according to Suetonius (Vesp. 9.1), originally an Augustan one. We might want to be sceptical of the velocia munera thermas (‘swift blessing of the baths’, Mart. Spect. 2.7), however. Noting that the orientation of the Baths of Titus corresponds to that of the Oppian wing of the Golden House, Coarelli (2007) 186–187 and Ball (2003) 250 suggest that the remarkably rapid construction of these baths points to the completion of a pre-existing Neronian project, rather than the execution of an entirely new design. On the Flavian redevelopment of this portion of the Golden House, see further the discussion of Raimondi Cominesi in this volume.

- Darwall-Smith (1996) 48–55; Griffin (1994) 312.

- Coleman (2006) 33.

- Levick (1999) 73; Hurlet (1993); Ramage (1983) 209–214.

- Syme (1958) 436–437, 439; Griffin (1990) 482–484; also McAlindon (1957); Taeger (1960) 303.

- Colini (1944). See also Buzzetti (1993); Darwall-Smith (1996) 50–52; Von Hesberg (2011) 109–110; Coarelli (2019) 279.

- The arches of this line of aqueduct, approaching the southern edge of the temple platform, appear on fragment 4a of the Severan Marble Plan: Rodríguez Almeida (1981) 63–65; Tucci (2006).

- Also noted by Raimondi Cominesi in this volume. Barrett (1996) 148 offers similar arguments about the western facade. Cf. Von Hesberg (2011) 110 and Varner (2017) 251, who suggest that the temple was in fact completed under Nero, and Vespasian ‘only rededicated the monument’, but also as Moormann (2003) 383–384, who argues that construction of the temple was never even begun under Nero.

- Cioncoloni and Sorella (2019).

- Barrett (1996) 148; Eck (1993) 51; also Turcan (1998) 165.

- Lollia: Tac. Ann. 12.22.1–3; Statilius: Ann. 12.59.1; Silanus: Ann. 13.1.1–2, Cass. Dio 61.6.4–5, cf. Plin. HN 7.58. Cf. Tac. Ann. 14.11.1–3, Luke (2013).

- This is not the place to relitigate the question of whether Claudius was, in fact, murdered: see the discussion in Aveline (2004). Important evidence for Agrippina’s association with Claudius’ cult is provided by the beautiful basanite sculpture, now in the museum of the Centrale Montemartini, showing Agrippina with her head veiled, apparently performing a sacrifice in her role as flaminica of her deif ied husband: see Talamo (2007); Gradel (2007). Flower (2006) 194 suggests that this statue, which was discovered in pieces on the Caelian, stood in Vespasian’s temple of Claudius. Varner (2004) 97–99 is more likely correct in suggesting that it went up under Nero and was subsequently smashed as part of public attacks on Agrippina’s memory following her murder (see Cass. Dio 61.16.2a).

- Nicols (1978) 21–22.

- Osgood (2011) 247, 250–251. It is worth noting that the empress was herself honoured as [θεᾶς Ἀγριπ]-πείνης [μητ]ρὸς (‘[goddess] mother Agrippina’, IvMag 158) in some parts of the empire, both during Claudius’ lifetime and after his deification (RPC I 1017, 2386–2388, 2349, 2685). Note especially IGR 4.560, which designates Nero as υἱόν φύ[σ]ει [θ]εᾶς [Ἀγριππίνης] (‘the son born of a goddess [Agrippina]’), on which see Hahn (1994) 186–197; Rose (1997) 47. So far as we know, Agrippina’s worship ended with her death and was not revived under the Flavians.

- AE 1968.549; IGR 4.1124; ITralles 54; RIC I2 150–151 nn. 1–7, 10. Rose (1997) 46; Hekster (2009) 104, (2015) 50–51; Hopkins (1978) 202. A full genealogy, listing Nero’s maternal grandfather Germanicus and great-grandfather Divus Augustus in addition to Divus Claudius, is typically adduced: CIL 2.4719 (= ILS 225), AE 1995.1633, CIL 2.183 (= ILS 5640), CIL 2.4884, RIB 92. Note especially CIL 6.40307, in which Nero is presented as part of a family group that also included Agrippina as divi Cl(audi) uxori (‘wife of deif ied Claudius’).

- Hekster (2015) 52–53; Levick (1990) 187.

- Cf. Strab. 5.3.8 (on Augustus’ ustrinum), with Cass. Dio 56.42.2–4 (on his funeral). Price (1987) 75–76, 93–97; Fishwick (2002) esp. 346–349.

- Osgood (2011) 251–256. I will not deal with the issue of the date of the Apocolocyntosis here. The consensus view, elaborated by Nauta (1987), associates it with the Saturnalia of 54, shortly after Claudius’ death.

- References to Claudius as a theos in the edict of Ti. Julius Alexander (under Galba, OGIS 669 = IGR 1.1263, 1.26, 27–28, 29) are likewise imperfect evidence for continuity of practice under Nero, but at least demonstrate that his divinity was not altogether forgotten before the Flavians came to power.

- Fishwick (1972).

- CIL 2. 4888, CIL 3.6123, IRT 341, AE 1999.1397, AE 1913.193, RMD 4.202 (all datable to 61). Cf. Tac. Ann. 14.60–64, Cass. Dio 62.13.1.

- RIC I2 186 nn. 619–622; RPC I.3647, 3652–3653; RPC I.4122–4123.

- RMD 2.79 (65), AE 1969/70.443 (66), CIL 11.1331 (67), CIL 10.8014 (67–68?).

- As noted above, n. 19, the tracing of Nero’s lineage back to Germanicus, Tiberius, and Divus Augustus is not uncommon in Nero’s titulature. In the context of this inscription, it is worth noticing how the use of conventional patronymic formulas obscures the fact that these connections were matrilineal, thereby facilitating the erasure of Agrippina from Nero’s dynastic legacy. Unless otherwise noted, translations are my own.

- On the career, see Demougin (1992) 489–492; Fentress (2003) 58–61. Eck (2010) 137 comments on the self-promotional aspect of the inscription.

- Cf. Demougin (1992) 492 n. 8.

- Charlesworth (1937) 56; Levick (1990) 190, (1999) 73; Birley (2005) 232–233. Cf. Philostr. VA5.29.2.

- See Nicols (1978) 22–34; also Levick (1999) 21–25.

- Schowalter (1993) 63–65; Price (1987) 81–82. Cf. Price (1984) 7–15; Fishwick (1987) 33; Gradel (2002) 4–7 and passim.

- See Bauman (1974) 71–85, 99–104.

- Price (1987) 80; Levick (1990) 187; Gradel (2002) 329–330.

- Bickermann (1929) 30.

- See, in general, Brunt (1977); Crawford (1996) 549–553.

- Hurlet (1993) 268; Peachin (2007) 84–85; Osgood (2011) 256, cf. 76. The omission of Galba, who would later be cited by the Flavians as a precedent (González [1986] 153 Table IIIA l. 20), relates to the as-yet unresolved nature of that emperor’s memory at the end of the year of four emperors: Gagé (1952); Zimmerman (1995) 60–62; cf. Tac. Hist. 4.40.1, Suet. Galb. 23.

- Levick (1999) 71.

- Griffin (199 4) 312 –313.

- Charlesworth (1937) 58; Levick (1990) 191; Griffin (1994) 311.

- González (1986) 153 Table IIIA ll. 17–22: dum ne quit eorum / omnium, quae supra scripta sunt, adversus leges plebescita senatus-/ve consulta edicta decreta constitutiones divi Aug(usti) [Ti(beri) I]uli Caesa-/ris Aug(usti), Imp(eratoris) Galbae Caesaris Aug(usti), Ti(beri) Claudi Caesaris Aug(usti), Imp(eratoris) Vespasia-/ni Caesaris Aug(usti), Imp(eratoris) Titi Caesaris Vespasiani Aug(usti), Imp(eratoris) Caes(aris) Domitiani / Aug(usti), pontif(icis) max(imi), p(atris) p(atriae) fiat, also 32–37; VA 10–15; IX A 24–28.

- Cf. González (1986) 153 Table IIIA ll. 1–2: ex edicto [I]mp(eratoris) Vespasiani Caesaris Aug(usti)Imp(eratoris)ve / T(iti) Caesaris Vespasiani Aug(usti) aut Imp(eratoris) Caesaris Domitiani Aug(usti), also 24–25, 48–49, IIIB 1–2. Cf. the lex Salpensana (CIL 2.1963 = FIRA I2 23) 6–7, 14–15.

- Scott (1936) 61–83; Darwall-Smith (1996) 153–178; Tuck (2016) 118–123.

- González (1986) 156 Table IIIB ll. 40–43: iurato in con-/tione per Iovem et divom Aug(ustum)et divom Claudium et divom Vespasi-/anum Aug(ustum) et divom Titum Aug(ustum) et genium Imp(eratoris) Caesaris Domitiani / Aug(usti) deosque Penates, also VB 32–35, VIIA 3–5, VIIIA 18–20, VIIIB 37–39, VIIIC 54–56. Cf. the lex Salpensana (CIL 2.1963 = FIRA I2 23) 30–31 and the lex Malacitana (CIL 2.1964 = FIRA I2 2 4) 15–19 .

- Charlesworth (1937) 59; Levick (1990) 187. Cf. Ascon. Sc. 45 (p. 27 Clark), Suet. Vesp. 9.1. Claudius as divus occurs more frequently in Pliny the Elder (HN 2.99, 3.141, 146, 5.20, 8.37, etc.), but the title is still frequently omitted (cf. 2.92, 3.119, 7.159, etc.), especially in citations of Claudius as an author (5.63, 6.27, 6.31, etc.).

- Gradel (2002) 332. Cf. Price (1987) 80 on the status of divi in Roman inheritance law.

- CIL 6.930 (= ILS 244) 2, 5, 20, etc., González (1986) 153 IIIA 19, etc. (quoted above, n. 42).

- Griffin (1994) 311: ‘his reputation was too complex to allow Claudius to become the kind of model that Augustus was’. See especially McAlindon (1957).

- Griffin (1994) 314; Levick (1999) 83, 132.

- Taeger (1960) 329–330, cf. Suet. Vesp. 7.2. See also Scott (1936) 3–17; Hopkins (1978) 232.

- Fishwick (1965) 155–167, (1987) 221, 241, 257–258; Deininger (1965) 28–31.

- Scott (1936) 61f f.; Taeger (1960) 334, 338–354; Friesen (1993); Elkins (2014); Laird (2015) 147–165; Tuck (2016) 118–123.

- In this regard, there may be a potential connection between Domitian’s Templum Gentis Flaviae, which was built on the Quirinal on the former site of his father’s house (Suet. Dom. 1), and the temple of Claudius, which Coarelli (2000) suggests (on the basis of Suet. Claud. 6.2 and Tib. 48) stood on the site of Claudius’ former residence on the Caelian.

- Hopkins (1978) 203; Beard, North, and Price (1998) 209–210, 253; Gradel (2002) 287–288.

- Hekster (2009) 104.

- Bickermann (1929) 2–4, 28–31; Price (1987) 87–91; Peppel (2003) 72–75. My omission of the deified female members of the imperial household from this narrative is admittedly arbitrary: see Hahn (1994); McIntyre (2016) 3–4, 93–109. First-century divae differed from divi in important ways, however, insofar as they did not have their own temples in Rome and, with the notable exception of Diva Augusta (Livia), their worship did not typically outlast the reign of the emperor who deified them. Reliance on patronymic formulas such as divi filius also meant that a woman’s divinity did not contribute to the prestige of her heirs in the same way that a deified father did.

- The most important of these is perhaps the problem of its date. A delay of several months, established by Buttrey (1976), may have had something to do with Titus’ decision to abolish prosecutions for asebeia (Dio [Xiph.] 66.19.1–2): see Gallia (2019).

- Scott (1936) 18–19; Taeger (1960) 330; Fishwick (1965) 155; Hopkins (1978) 216.

- Schmidt (1988); followed by Levick (1999) 197–198.

- Harper (2017) 84.

- Even Augustus could joke about his own divinity: Suet. Aug. 71.3, Quint. Inst. 6.3.77. Price (19 84) 1 1 4–1 16.

- I would like to thank the organizers, participants, and audience of the conference in Amsterdam for many stimulating discussions, which helped me to refine my thinking about this material, and the editors of this volume for suggesting a number of improvements to my text.

Bibliography

- Albertson, F. C. (2001). Zenodorus’s ‘Colossus of Nero’. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 46, 95–118.

- Aveline, J. (2004). The Death of Claudius. Historia, 53, 453–475.

- Ball, L. F. (2003). The Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution. Cambridge University Press.

- Barrett, A. A. (1996). Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire. Routledge.

- Bartsch, S., Freudenburg, K. & Littlewood, C. (Eds.) (2017). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Nero. Cambridge University Press.

- Bauman, R. A. (1974). Impietas in Principem: A Study of Treason against the Roman Emperor with Special Reference to the First Century A.D. Beck.

- Beard, M., North, J. & Price, S. (1998). Religions of Rome. Cambridge University Press.

- Bickermann, E. (1929). Die römische Kaiserapotheose. Archiv für Religionswis-senschaft, 27, 1–31.

- Birley, A. (2005). The Roman Government of Britain. Oxford University Press.Brunt, P. A. (1977). Lex de Imperio Vespasiani. Journal of Roman Studies, 67, 95–116.

- Burnand, Y., Le Bohec, Y. & Martin, J.-P. (Eds.) (1998). Claude de Lyon: Empereur Romain. Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne.

- Buttrey, T. V. (1976). Vespasian’s Consecratio and the Numismatic Evidence. Historia, 25, 449–457.

- Buzzetti, C. (1993). Claudius, divus, templum. Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, 1, 277–278.

- Cancik, H. & Hitzl, K. (Eds.) (2003). Die Praxis der Herrscher verehrung in Rom und seinen Provinzen. Mohr Siebeck.

- Cannadine, D. & Price, S. (Eds.) (1987). Rituals of Royalty: Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Charlesworth, M. P. (1937). Flaviana. Journal of Roman Studies, 27, 54–62.

- Cioncoloni, R. & Sorella, R. (2019). Un contesto di età giulio-claudia da scavi inediti all’Antiquarium del Celio. In Parisi Presicce, L. & Spagnuolo, L. (Eds.) Claudio Imperatore: Messalina, Agrippina e le ombre di una dinastia (pp. 283–285). ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider.

- Coarelli, F. (2000). Il tempio di Minerva Capta sul Celio e la domus di Claudio. Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, 70, 209–218.

- Coarelli, F. (2007). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide (J. J. Clauss and D. P. Harmon, Trans). University of California Press.

- Coarelli, F. (2019). Il tempio del Divo Claudio. In Parisi Presicce, L. & Spagnuolo, L. (Eds.) Claudio Imperatore: Messalina, Agrippina e le ombre di una dinastia (pp. 279–282). ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider.

- Coleman, K. M. (2006). M. Valerii Martialis Liber Spectacularum. Oxford University Press.

- Colini, A. M. (1944). Storia e Topografia del Celio nell’Antichità. Edizioni Quasar.

- Crawford, M. H. (Ed). (1996). Roman Statutes. Institute of Classical Studies.

- Croisille, J.-M., Martin, R. & Perrin, Y. (Eds.) (1999). Neronia V. Néron: histoire et légende: Actes du Ve colloque international de la SIEN, Clermont-Ferrand et Saint-Etienne, 2–6 novembre 1994. Latomus.

- Darwall-Smith, R. H. (1996). Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Latomus.

- de Blois, L. et al. (Eds.) (2003). The Representation and Perception of Roman Imperial Power:Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the International Net work Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.-A.D. 476), Rome, March 20–23, 2002. Brill.

- Deininger, J. (1965). Die Provinziallandtage der römischen Kaiserzeit. Beck. Demougin, S. (1992). Prosopographie des chevaliers romains julio-claudiens (43 av. J.- C .–70 ap. J.- C .). École française de Rome.

- Eck, W. (1993). Agrippina die Stadtgründerin Kölns: Eine Frau in der frühkaiser-zeitlichen Politik. Greven.

- Eck, W. (2010). Monument und Inschrift: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur senatorischen Repräsentation in der Kaiserzeit. De Gruyter.

- Elkins, N. (2014). The Procession and Placement of Imperial Cult Images the Colosseum. Papers of the British School at Rome, 82, 73–107.

- Fentress, E. (2003). Cosa V: An Intermittent Town, Excavations 1991–1997. University of Michigan Press.

- Fishwick, D. (1965). Vae Puto Deus Fio. Classical Quarterly, 15, 155–157.

- Fishwick, D. (1972). Templum Dio Claudio Constitutum. Britannia, 3, 164–181.

- Fishwick, D. (1987). The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, Volume I.2 vols. Brill.

- Fishwick, D. (2002). The Deification of Claudius. Classical Quarterly, 52, 341–349.

- Flower, H. I. (2006). The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture. University of North Carolina Press.

- Friesen, S. J. (1993). Twice Neokoros: Ephesus, Asia and the Cult of the Flavian Imperial Family. Brill.

- Gagé, J. (1952). Vespasien et la mémoire de Galba. Revue des Études Anciennes, 54, 290–315.

- Gallia, A. B. (2016). Remaking Rome. In Zissos (Ed.) A Companion to the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome (pp. 148–165). Wiley Blackwell.

- Gallia, A. B. (2019). Vespasian’s Apotheosis. Classical Quarterly, 69.1, 335–339.

- González, J. (1986). The Lex Irnitana: A New Copy of the Flavian Municipal Law. Journal of Roman Studies, 76, 147–243.

- Gradel, I. (2002). Emperor Worship and Roman Religion. University of Oxford Press.

- Gradel, I. (2007). Agrippina, Flaminica of Divus Claudius. In Moltesen, M. & Nielsen, A. M. (Eds.) (2007). Agrippina Minor: Life and Afterlife, Liv og eftermaele (pp. 67–70). Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

- Griffin, M. (1990). Claudius in Tacitus. Classical Quarterly, 40, 482–501.

- Griffin, M. (1994). Claudius in the Judgement of the Next Half-Century. In Strocka, V. M. (Ed.) (1994). Die Regierungszeit des Kaisers Claudius (41–54 n. Chr.): Umbruch oder Episode? (pp. 307–316). Zabern.

- Hahn, U. (1994). Die Frauen des römischen Kaiserhauses und ihre Ehrungen im griechischen Osten anhand epigraphischer und numismatischer Zeugnisse von Livia bis Sabina. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag.

- Harper, K. (2017). The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease and the End of an Empire. Princeton University Press.

- Hekster, O. (2009). Honoring Ancestors: The Dynamic of Deification. In Hekster, O., Schmidt-Hofner, S. & Witschel, C. (Eds.) (2009). Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in the Roman Empire (pp. 95–110). Brill.

- Hekster, O. (2015). Emperors and Ancestors: Roman Rulers and the Constraints of Tradition. Oxford University Press.

- Hekster, O., De Kleijn, G. & Slootjes, D. (Eds.) (2007). Crises and the Roman Empire. Brill.Hekster, O., Schmidt-Hofner, S. & Witschel, C. (Eds.) (2009). Ritual Dynamics and Religious Change in the Roman Empire. Brill.

- Hopkins, K. (1978). Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge University Press.

- Hurlet, F. (1993). La Lex de imperio Vespasiani et la légitimité augustéenne. Latomus, 52, 261–280.

- Laird, M. L. (2015). Civic Monuments and the Augustales in Roman Italy. Cambridge University Press.

- La Rocca, E. (2017). Staging Nero: Public Imagery and the Domus Aurea. In Bartsch, S., Freudenburg, K. & Littlewood, C. (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Nero (pp. 195–212). Cambridge University Press.

- Levick, B. (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press.

- Levick, B. (1999). Vespasian. Routledge.

- Luke, T. (2013). From Crisis to Consensus: Salutary Ideology and the Murder of Agrippina. Illinois Classical Studies, 38, 207–228.

- McAlindon, D. (1957). Claudius and the Senators. American Journal of Philology, 78, 279–286.

- McIntyre, G. (2016). A Family of Gods: The Worship of the Imperial Family in the Latin West. University of Michigan Press.

- Moltesen, M. & Nielsen, A. M. (Eds.) (2007). Agrippina Minor: Life and Afterlife, Liv og eftermaele. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

- Moormann, E. M. (2003). Some Observations on Nero and the City of Rome. In de Blois, L. et al. (Eds.) The Representation and Perception of Roman Imperial Power:Proceedings of the Third Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.-A.D. 476), Rome, March 20–23, 2002 (pp. 376–388). Brill.

- Nauta, R. R. (1987). Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis as Saturnalian Literature. Mnemosyne, 40, 69–96.

- Nicols, J. (1978). Vespasian and the Partes Flavianae. Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Osgood, J. (2011). Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press.

- Parisi Presicce, L. & Spagnuolo, L. (Eds.) (2019). Claudio Imperatore: Messalina, Agrippina e le ombre di una dinastia. ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider.

- Peachin, M. (2007). Exemplary Government in the Early Roman Empire. In Hekster, O., De Kleijn, G. & Slootjes, D. (Eds.) Crises and the Roman Empire (pp. 75–93). Brill.

- Peppel, M. (2003). Gott oder Mensch? Kaiserverehrung und Herrschaftskontrolle. In Cancik, H. & Hitzl, K. (Eds.) Die Praxis der Herrscher verehrung in Rom und seinen Provinzen (pp. 69–95).Mohr Siebeck.

- Price, S. R. F. (1984). Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press.

- Price, S. R. F. (1987). From Noble Funerals to Divine Cult: The Consecration of Roman Emperors. In Cannadine, D. & Price, S. (Eds.) Rituals of Royalty: Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies (pp. 56–105). Cambridge University Press.

- Ramage, E. S. (1983). Denigration of Predecessor under Claudius, Galba, and Vespasian . Historia, 32, 201–214.

- Ripoll, F. (1999). Aspects et fonction de Néron dans la propagande impériale f la-vienne. In Croisille, J.-M., Martin, R. & Perrin, Y. (Eds.) Neronia V. Néron: histoire et légende: Actes du Ve colloque international de la SIEN, Clermont-Ferrand et Saint-Etienne, 2–6 novembre 1994 (pp. 137–151). Latomus.

- Rodríguez Almeida, E. (1981). Forma Urbis Marmorea. Aggiornamento Generale 1980. Edizione Quasar.

- Rose, C. B. (1997). Dynastic Commemoration and Imperial Portraiture in the Julio-Claudian Period. Cambridge University Press.

- Schmidt, M. G. (1988). Claudius und Vespasian: Eine neue Interpretation des Wortes ‘vae, puto, deus fio’ (Suet. Vesp. 23 , 4). Chiron, 18, 83–89.

- Schowalter, D. N. (1993). The Emperor and the Gods: Images from the Time of Trajan. Fortress.

- Scott, K. (1936). The Imperial Cult under the Flavians. Kohlhammer.

- Steinby, E. M. (Ed.) (1993–2000). Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae. 6 vols. Edizioni Quasar.

- Strocka, V. M. (Ed.) (1994). Die Regierungszeit des Kaisers Claudius (41–54 n. Chr.): Umbruch oder Episode? Zabern.

- Syme, R. (1958). Tacitus. Clarendon Press.

- Taeger, F. (1960). Charisma: Studien zur Geschichte des antiken Herrscherkultes. Kohlhammer.

- Talamo, E. (2007). I Ritrovamenti Archeologici sul Celio e la Scoperta della Statua di Agrippina Orante. In Moltesen, M. & Nielsen, A. M. (Eds.) Agrippina Minor: Life and Afterlife, Liv og eftermaele (pp. 95–111). Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

- Tomei, M. A. & Rea, R. (Eds.) (2011). Nerone. Catalogo della mostra (Roma, 13 aprile–18 settembre 2011). Electa.

- Tucci, P. L. (2006). Ideology and Technology in Rome’s Water Supply: castella, the Toponym AQVEDVTIV M, and Supply to the Palatine and Caelian Hills. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 19, 94–120.

- Tuck, S. L. (2016). Imperial Image-Making. In Zissos, A. (Ed.) A Companion to the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome (pp. 109–128). Wiley Blackwell.

- Turcan, R. (1998). Templum divi Claudii. In Burnand, Y., Le Bohec, Y. & Martin, J.-P. (Eds.) Claude de Lyon: Empereur Romain (pp. 161–167). Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne.

- Varner, E. R. (2004). Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Brill.

- Varner, E. R. (2017). Nero’s Memory in Flavian Rome. In Bartsch, S., Freudenburg, K. & Littlewood, C. (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Nero (pp. 237–257). Cambridge University Press.

- Von Hesberg, H. (2011). L’Attività Edilizia a Roma all’Epoca di Nerone. In Tomei, M. A. & Rea, R. (Eds.) Nerone. Catalogo della mostra (Roma, 13 aprile–18 settembre 2011) (pp. 108–117). Electa.

- Zimmermann, M. (1995). Die restitutio honorum Galbas. Historia, 44, 56–82.

- Zissos, A. (Ed.) (2016). A Companion to the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome. Wiley Blackwell.

Chapter 2 (33-54) from Flavian Responses to Nero’s Rome, edited by Mark Heerink and Esther Meijer (Amsterdam University Press, 09.29.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license.