Exploring Britain’s railways from 1812 to 2007.

1812: The First Effective Locomotive-Powered Railway

The coal-carrying Middleton Railway, near Leeds, introduced rack-and-pinion locomotives to haul its trains in 1812. Formerly, coal had been transported from the Middleton pits by wagon way, using horse-drawn wagons.

The locomotive’s cylinders drove the pinions through right-angled cranks, so that the engine would start wherever it came to rest.

It is widely considered as being the first commercial railway to make effective use of steam locomotive power, although several accidents in the early years of operation later resulted in the reintroduction of horse haulage.

1830: Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The opening of the railway signified the birth of modern railways.

It was the first inter-city railway which used locomotives and the first to offer a timetabled passenger service. Its success and popularity proved the viability of the railways and led to the huge expansion in the ‘railway network’.

The actual opening was, however, marred by the death of MP William Huskisson who was fatally injured when an engine ran over his legs. This is often cited as the first railway fatality.

1841: Thomas Cook Runs His First Rail Excursion

Railways changed people’s leisure habits, allowing large numbers of people to travel cheaply to events and holiday destinations for the first time.

Cook was one of the most successful travel agents to exploit the new mode of transport – originally negotiating with the railway a package deal for a group of temperance campaigners to attend a rally – and there were many others whose businesses were not as long-lived. But excursion trains were far from travelling idylls; they were overcrowded, noisy and slow, and early ones even used open wagons.

1842: Queen Victoria Makes Her First Journey by Rail

Persuaded by her husband Albert, an enthusiast for new technology, the Queen expressed her desire to journey to London to the GWR with two day’s notice.

The Morning Chronicle reported the Queen saying “Not quite so fast next time, Mr Conductor, if you please,” but the journey convinced her of the merits of the railway and she travelled regularly by train throughout the rest of her reign.

The patronage of the royal family was a significant factor in increasing the popularity of the railways among the general public.

1846: Height of ‘Railway Mania’

Applications for powers to construct and operate a railway were granted to companies by the passing of Private Acts of Parliament. During the height of railway expansion, in 1846, there were 272 Acts of Parliament for proposed railway lines.

The increasing price of railway shares led to a speculative frenzy, but a subsequent economic downturn and overexpansion by the railways led to a deterioration in financial performance.

Thousands of people’s lives changed through their investment in railway shares, and entrepreneurs such as ‘railway king’ George Hudson made spectacular fortunes, and suffered equally spectacular falls.

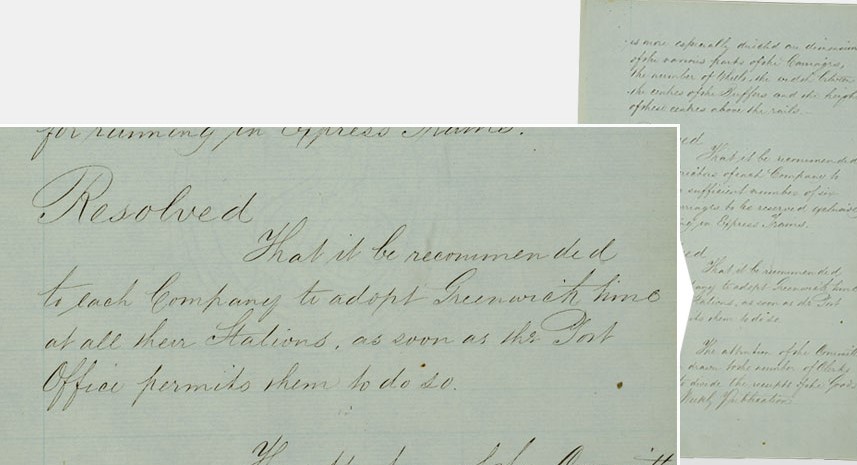

1847: Greenwich Mean Time Adopted by the Railway Clearing House

The improvements in rapid communication and travel in the early 19th century made accurate and consistent timekeeping increasingly important. In 1847 the Railway Clearing House stated Greenwich Mean Time should be adopted as the time by all stations. This subsequently led to the synchronising of time across the country and a single national time zone being created.

Previously there had been local variations in time. These time inconsistencies made it difficult to create reliable national timetables. The railways encouraged a single standard time to be adopted to improve both efficiency and safety.

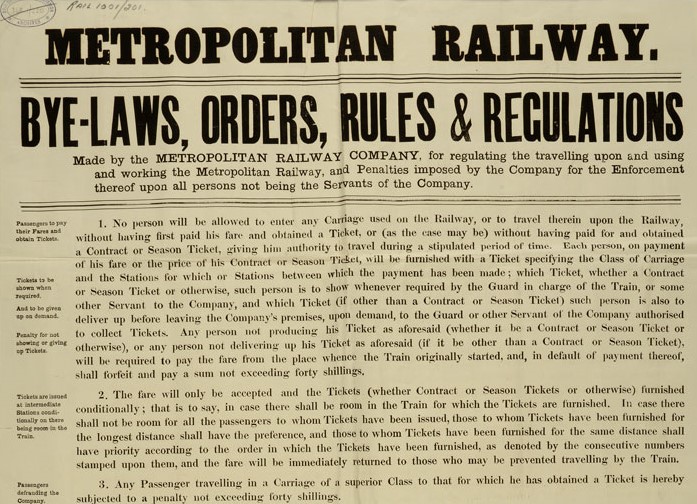

1863: Opening of the First Underground Railway

Although an underground railway linking the City of London with the mainline terminus stations had originally been proposed in the 1830s, construction of the first line, covering 3.75 miles, and 7 stations, between Farringdon Street and Bishop’s Road (Paddington) did not commence until 1860, using a ‘cut-and-cover’ method of tunnel building.

When this line opened to the public on 10 January 1863, with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, it was the world’s first underground railway, and eventually became part of the network brought together as London Underground.

1864: The ‘Müller Murder’

Thomas Briggs became the first person to be murdered on Britain’s railways in 1864.

The 69-year-old banker was beaten and robbed while he travelled in the first class carriage on the North London Railway. Franz Müller was eventually charged and hanged before a crowd outside Newgate prison.

It created a media sensation, as well as heightening fears about railway safety.

Partly in response to the case, four years later the Regulation of Railways Act led to communication cords linked to the guard’s van being placed on non-stop trains travelling more than 20 miles.

1889: Armagh Rail Disaster

This horrific crash killed 80 people, including many children travelling on a Sunday school excursion train, when an inadequately braked portion of a divided train ran backwards and collided with another service.

Following the accident, the state took a greater role in the safety and regulation of the railways, introducing legal requirements for a number of safety measures. It led to continuous automatic braking ( a brake system that operates along the length of the train, even when the connecting hose is broken) becoming mandatory.

1892: Demise of Broad Gauge

In 1830s Britain there were two widths, or gauges, of railway track. The engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel favoured rails 7 feet apart (Broad Gauge) on the Great Western Railway, while George and Robert Stephenson used a gauge measuring 4 ft 8 ½ inches (Standard Gauge).

While Broad Gauge had advantages, more lines used the narrower, and cheaper, Standard Gauge system. Over time the advantages of a national standard gauge railway outweighed the benefits of wider tracks. Gradually all broad gauge lines were converted to standard gauge, ending with the Exeter to Truro route in May 1892.

1900: Taff Vale Railway Strike

Workers at the Taff Vale Railway Company, (members of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants), striking to protest against the company’s treatment of an employee ran a sabotage campaign to disrupt the railways’ daily running by replacement workers.

The following year, the railway company sued the union for damages and won. The ruling outlined that unions could be liable for the loss of profit from strike action.

It is known as one of the key events leading to the formation of the Labour party, which later in a coalition government passed the Trades Disputes Act 1906, overriding the ruling.

1914: Formation of the Railway Executive Committee

When war was declared in 1914, the 130 extant railway companies were taken over by the government in the form of the Railway Executive Committee, consisting of the general managers of the major railway companies. Rolling stock was pooled, workshops were given over to munitions work and locomotives were sent overseas for the war effort.

Railwaymen were encouraged to join the Royal Engineers, contributing to army operations as part of the Railway Operating Division and delivering troops, ammunition and supplies to the front lines.

The operation was seen by some as a pre-cursor to the nationalisation of the railways.

1915: Quintinshill Rail Disaster

The crash involving five trains at Quintinshill, Scotland on 22 May 1915 caused 226 deaths. The majority of the fatalities were soldiers from the Royal Scots regiment, who had been travelling on one of the two trains involved in the initial collision.

The initial investigation laid the blame for the accident with two signalmen, who were later prosecuted and imprisoned for criminal negligence.

Railway safety improvements such as the use of track circuits and signaller reminder devices were introduced to prevent similar railway accidents in the future.

1926: Use of Amateurs on the Railways during the General Strike

The Trade Union Congress called a General Strike on 4 May 1926 in response to government plans to change working conditions for coal miners.

Two million workers across Britain, including railwaymen, went on strike. The railway companies resorted to recruiting volunteers with no railway experience to act as train drivers and signalmen. These amateurs ran the risk of violence from strikers, and the Flying Scotsman was deliberately derailed in Northumberland. The strike lasted nine days, and the following year the government passed the Trade Disputes Act which outlawed the sympathetic strike action that had created the General Strike.

1950: Campaign to Preserve Talyllyn Railway

Originally built to carry slate to the mid-Wales coast, the Talyllyn Railway was the first railway in the world to be preserved and run as a heritage line by volunteers. Since preservation, the line has been extended and new rolling stock acquired.

The campaign to save the railway marked the beginning of the United Kingdom railway heritage movement, which has grown into a significant part of tourist and local economies, with several hundred heritage railways operating in the UK.

1955: British Railways Modernisation Plan

Intended to bring Britain’s railways up-to-date and to eliminate their deficit by increasing speed, reliability and efficiency, the Modernisation Plan in many respects was a failure, involving expensive mistakes and missed opportunities.

The phasing-out of steam traction engines announced in the plan meant that many steam locomotives were scrapped when only a few years old, and often before a reliable and practical diesel or electric equivalent was available. However, the diesel and electric trains it introduced generally changed travelling conditions for the better for passengers and crew.

1963: Publication of ‘The Reshaping of Britain’s Railways’, Known to Many as ‘The Beeching Report’

The early growth of railways led to many lines in rural areas which, in some cases, never made a profit.

In 1961 Dr Richard Beeching was appointed Chairman of the British Railways Board, tasked with returning the industry to profitability. His controversial report called for the closure of one-third of the country’s less profitable stations, and the cuts which were eventually made resulted in the loss of many branch lines. Critics accused Beeching of ignoring the social cost of the cuts and increasing dependency on cars. However, Beeching did also equip BR to compete more effectively with road transport for bulk freight traffic.

1965: Launch of the New British Rail Corporate Identity

One of the biggest industrial rebranding exercises ever undertaken, and supposedly signposting a bold future, the 1965 rebranding introduced the blue liveries, the famous double arrow logo (symbolising the direction of travel on a double track railway) and a new typeface, ‘Rail Alphabet’, which was also adopted by the NHS and the British Airports Authority.

The double arrow logo survived the demise of British Rail and is employed as a generic symbol denoting railway stations under the National Rail brand.

1994: The Channel Tunnel Opens

The Channel Tunnel has added a new dimension to European business and leisure travel, and linked mainland UK and continental Europe for continuous travel for the first time. It has driven the development of High Speed rail lines in Britain. However, the idea of a tunnel was first conceived in the early 19th century and the idea of some kind of ‘fixed link’ spanning the Channel goes back to the Romans. Ideas have included boats lashed together, a string of artificial islands and several bridges, as well as numerous tunnel schemes preceding the eventual completion of the Channel Tunnel.

2007: Launch of ‘High Speed 1’, the First High Speed Line

Subject to impassioned economic and environmental debate during its construction, HS1 is Britain’s first genuine high speed line, with speeds of 186mph possible in some sections. As well as high speed services through the Channel Tunnel, it has enabled Kent-London Javelin commuter services to reach speeds of 140mph, and also allows European container freight to reach London for the first time.

HS1’s success is playing a major part in the debates around HS2, the proposed high speed link from London to the North.

Originally published by The UK National Archives under Crown CopyrightOpen Government Licensing.