A selection of books, articles, and resources on conceptualizing race in the Ancient world.

Introduction

Race is inherently unstable. It is a composite identity not imparted on someone by innate biology but encoded through a series of political, cultural, social, geographical, and moral metamorphoses. Yet this instability has long justified the exclusion of race’s critical examination, discussion, and pedagogy in the study of texts, arts, and artifacts of antiquity. The absence of scholarship on race has delimited the potential of Classics and fettered its intellectual relevance and position in the modern academy.

If race is not just one thing, then the methods used to approach it cannot be either. The following bibliography aims to fill this gap in the discussion of race in antiquity, creating an accessible and coherent list of sources from various disciplines that seek to explicate some facet of race, racialization, and racism in the ancient world. The bibliography opens with the question, “How can we conceptualize race in the ancient world?”, with each subheading providing possible answers in the form of theories, methodologies, genres, and innovations that are not necessarily Classical but speak to the matters of antiquity. The sources included were chosen for the example they provide of how one may conduct a research project regarding material as political and obscured as race, without sacrificing rigorous and tangible investigation. These sources also introduce frameworks that are innovative and compelling, and even when they do not directly address the ancient world, still provide powerful suggestions and tools for doing so.

Race via Afrocentrism

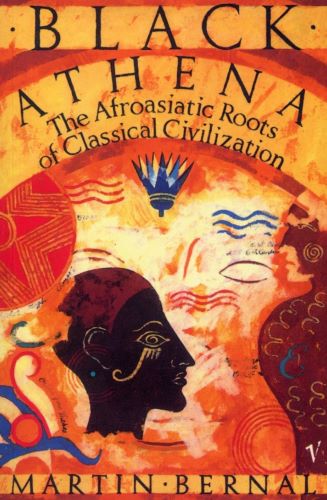

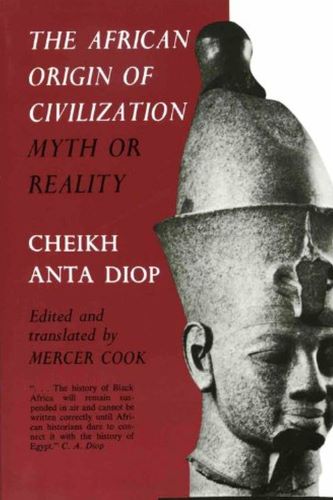

Afrocentrism is a movement in the humanities to focalize – rather than view as an object, responder, or colonized subject – the African continent. While this explicitly anti-racist approach was pioneered by Drusilla Dunjee Houston in her 1926 book Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, and was carried on by scholars such as Cheikh Anta Diop, its implications for ancient studies have become most apparent since Martin Bernal published his extremely influential and controversial multi-volume book Black Athena in the 1980s. In Classics and Ancient Studies, Afrocentrism has primarily been utilized as a lens for exploring Egypt’s relationship to Nubian and subSaharan African cultures. The following sources explore methods and case studies of Afrocentrism that examine not only Egypt, but also Nubia, Ethiopia, and Pan Africanism.

Presented in three equally monumental volumes, the first published in 1987, Bernal’s Black Athena is perhaps the most controversial work in the modern discipline of Classics. Bernal, the grandson of one of the twentieth century’s most famous Egyptologists, was a scholar of ancient China by training. As a result of studying Semitic languages and cultures, Bernal found new interest in what he saw to be the Afroasiatic roots of Greek civilization. In essence, Bernal asserts that cultural, linguistic, and religious similarities demonstrate that Greek civilization took its lineage – as Herodotus and other ancient authors assert – from Egyptian civilization, making Classical civilization ultimately of African heritage. Although the evidence he mobilizes has been frequently contested, Black Athena is important in that it explores the various ways in which Classics as a discipline has been invested in closely guarding the purity of its European roots. Bernal’s text – which won the American Book Award – generated widespread debate in the field of Classics, but its reception in Black studies and other areas has been largely positive and productive. (ALR, 2020)

Further reading on Black Athena and its tumultous reception can be found in Denise McCoskey’s article in Eidolon, “Black Athena, White Power.” See also Mary Lefkowitz’s hearty rebuke of Bernal in her book, Not Out Of Africa: How “Afrocentrism” Became An Excuse To Teach Myth As History, to which Bernal responded in his 1987 work, Black Athena Writes Back.

Cheikh Anta Diop, born in Francophone Senegal, wrote numerous histories that offered a cohesive account of Africa’s ancient past. His most frequent focus was on Ancient Egypt. Diop believed that racial-ethnic terminology such as “Mediterranean,” “Middle-Eastern,” and even “Caucasian” served to dissociate Egypt from its African identity and tradition. Importantly, Diop wanted the term “black,” in academic literature and common vernacular, to have as broad a meaning as the term “white,” leading him to write numerous histories on Egypt that focused on the Blackness of the population. Like Bernal, Diop is a controversial figure in the academy. His view that Egypt should be viewed as a thoroughly African civilization, however, and many of his insights and observations are important.

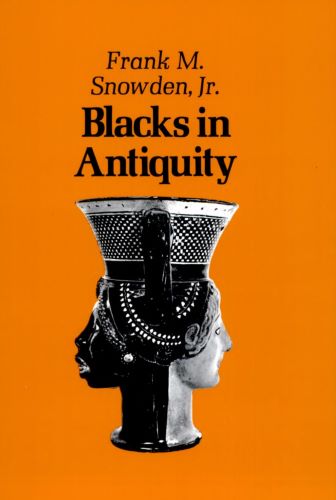

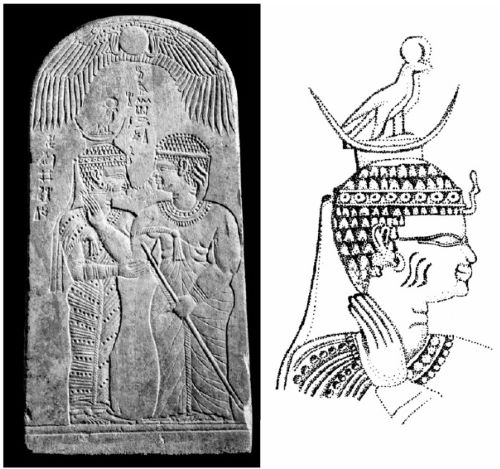

In his far-reaching project, Frank Snowden, renowned professor of Classics at Howard University, presents a history of Blackness in the ancient world through a transdisciplinary examination of “Ethiopians.” Ethiopian, as Snowden demonstrates, became in the Greco-Roman world a catchall term for Black-skinned individuals, and particularly those from regions south of Egypt’s first cataract. Obvious divisions existed among those in this racial category, and Snowden demonstrates the rich and varied nature of the surviving evidence. Using archeological, historical, and literary sources from both Greek and Roman civilizations, Snowden foregrounds and illuminates the heterogeneous experiences of Africans in contexts of culture contact. In doing so, he problematizes the notion that modern biases can be easily transposed upon the peoples of the ancient world. This is an excellent text for those seeking visual and material sources regarding race in antiquity.

A decade after Blacks in Antiquity, Snowden wrote Before Color Prejudice. Snowden’s essential supposition in the text – that not only was there no color prejudice against Black Africans in antiquity but that the group was by and large highly favored and respected – is a complicated view. Snowden argues that while “Ethiopians” (mostly Nubians and sub-Saharan Africans) encountered in the classical world as slaves suffered from the stigma common to all slaves, rich Ethiopians were respected and their poorer counterparts weren’t discriminated against on the basis of their skin color. Thus, Snowden offers an image of race in the ancient world that rewrites the assumptions of post-colonial logics. Race and racial projects are largely about power; so, the fact that – unlike Egypt – “Ethiopia” remained unconquered meant, in Snowden’s view, that its people could be known for other traits such as piety and righteousness. It’s important to note that Before Color Prejudice was met with skepticism by some Black scholars in other departments, famously Orlando Patterson, whose 1982 text Slavery as Social Death served as antithesis to Snowden’s. To some extent such differences in opinion rest on whether one privileges literary satire, artistic caricature, and evidence for Black slaves or whether one focalizes instead the plentiful evidence for flattering depictions of free Ethiopians in art and text.

Race via Archaeology and Material Culture

When it comes to approaching race in the ancient world, the largest barrier is evidence, the qualifications for which are ever-shifting and often impossible to meet. Insofar as ethnic and racial identities often overlap, the work of archaeologists in exploring the material artifacts of antiquity can provide an important window into past constructions of identity. This is particularly true with reference to non-elites and to women. Thus, archaeology often serves as an irreplaceable counterbalance to the biases inherent in ancient written evidence and artistic production. The following sources not only present findings from excavations but include theoretical frames. Some, however, focus less on evidence than they do on ethics and argue for re-envisioning the discipline.

Corrine Bonnet looks at archaeological evidence of ritual tophet structures in Punic Carthage, which are usually tied to an etic idea of Punic traditions of human sacrifice. As little written material from the colony survives, it is impossible to construct a purely emic understanding of the significance of the tophet and practices of human sacrifice based on written records. The chapter examines the unique position of Carthage as a colonial settlement that interacted with the indigenous population of North Africa and as a diaspora community with close ties to Phoenician culture and identity. It places its material culture in dialogue with the ideas of Punic-Carthaginian ethnicity as viewed from an etic Greek and/or Roman perspective. Punic-Carthaginian ethnicity and identity could be expressed, Bonnet argues, by the presence and ritual use of tophet structures in and outside of Punic Carthage. (LC, 2021)

As imperial Rome spread its dominion, it is often considered to have been completing the civilizing process of ‘Romanization.’ However, as Carr argues in this text, this is an outdated model. Romanization is really just a specified form of acculturation, which is a term that has been used historically as a unidirectional process of a dominant society implanting its cultural norms onto a subjugated society. Modern scholarship would argue that we should instead be considering multidirectional cultural exchange when we look at boundaries and interactions between ancient societies. Here, Carr employs the linguistic concepts of creolization and pidginization to analyze the material culture of early Roman Britain. So too, she asks if we can find people creating ‘pidgin’ artifacts in the wake of foreign infiltration and interactions. Carr argues that we cannot understand the Romans and the Britains to be two opposing, monolithic groups, because the archaeological record includes items that blend both societies. Carr demonstrates in particular how creolization is important because it allows “the non-elite native voice to be heard within the complex mix of hybrid Roman and non-Roman identities and counter-cultures which made up Roman Britain.” Carr’s approach in this work – using analytical tools usually applied exclusively to language formation in colonial settings – is an innovative alternative to outdated theories regarding colonizer-colonized relationships.

This work discusses plant remains from 8th-5th century BCE Kawa, a major urban center of the Napatan state in Nubia. Evidence of dates and grape plants may indicate the possibility of a plantation economy, which would have been made possible by the new irrigation systems introduced as a result of New Kingdom Egyptian colonialism. Fuller argues that the intensive agricultural work necessary to maintain such crops would have impacted conceptions of ethnicity in the region, as large groups of people would by necessity have been brought together, thus likely resulting in transculturation. So too, the shift to new crops may have caused a change in culinary habits—thereby affecting the foodways that constitute a key signifier of ethnic identity for many groups.

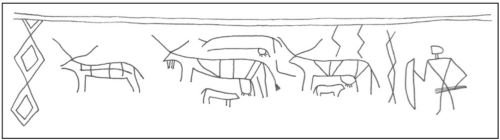

This book investigates the ethnic identity of the C-group people of Lower Nubia and how their cattle pastoralist lifestyle impacted their culture. While much is still not known about the C-Group, as they did not have a literary tradition, much can be extrapolated from their art, funerary practices, and the impression they left on their literate Egyptian neighbors. This article provides an overview of the C-group’s cultural trajectory from its presumed ethnogenesis in the late Old Kingdom until its seeming disappearance in the early New Kingdom. It also draws on ethnographic studies of cattle pastoralist societies to argue women were very likely responsible for milking and therefore also for manufacturing pottery. If so, women would have had a significant role in manufacturing many of the material signatures that archaeologists utilize to identify the culture ethnically.

In 2018, following decades of political pressure and social movements, the popular tide in France had shifted towards considering the possible restitution of the artifacts France had pillaged, looted, and otherwise unethically acquired during its colonial reign of northwestern Africa. As such, PM Macron commissioned French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese scholar Felwine Sarr to write a report on the impact of the lost artifacts on the African continent and the possible futures restitution may bring about. The report is a triumph of public intellectualism, bringing together centuries of context to the matter of cultural theft. The report humanizes “the artifact” not as an evidentiary thing that provides truth within the academy but as a holder of immense cultural and personal value, one whose absence deprives people of a past and whose presence is necessary in building futures. While archaeologists working with antiquity continue to excavate lands in whose presence they have little stake, an undeniably important pursuit, the Savoy-Sarr report is a grounding work that reframes the narrative life of artifacts and suggests the value of their remaining in their countries of origin. As of February 2021, no artifacts have been restituted to Africa from France.

Gillian Shepherd focuses on ethnic identity in ancient Sicily during a time when the island was home to native Sicilian populations, as well as Greek and Phoenician colonies/city-states. Thucydides, as well as other literary sources, offer insights into the etic perspectives of identity in ancient Sicily. Thucydides details the mother cities of Greek colonies in Sicily, the presence of Phoenicians, and the three main Sicilian native groups as Sicans, Elymians, and Sikels. Despite this clear delineation of ethnicities set forth in the ancient textual record, Shepherd argues that the material evidence of Sicily does not reflect these same clear-cut boundaries. The material culture of the native, the Phoenician, and the Greek populations incorporate elements of one another, especially in burial practices for particular social groups. These patterns of mixed assemblages and practices serve to delineate between families or social sub-groups within an ethnic group, rather than act as ethnic signifiers. Shepherd’s findings thus remind archaeologists and historians that material culture does not necessarily reflect one’s ethnicity, but instead may serve specific purposes in different contexts; even more, these findings could indicate a plurality of identities in which ethnic boundaries shift.

Much emphasis is placed on Egypt’s interactions with the Greco-Roman world, but understanding the relationship between Egyptians and ethnic others during the pharaonic era provides valuable perspective. Of critical importance to any meaningful study of race in antiquity are the various kingdoms of Nubia, which often rivaled or even surpassed Egypt in power and importance. Through examining the archaeological record at the colonial Egyptian settlement of Askut and cemetery at Tombos, Smith is able to demonstrate the ways in which shifting power dynamics between Egypt and Nubia radically altered the way ethnicity was performed and conceived. In Egyptian-occupied Nubia at the fortress of Askut, for example, Nubian cookware increased steadily over time. Residue analysis indicates that the food prepared in Nubian cookware differed from that prepared in Egyptian cookware, which suggests that – as in the American Southwest –colonial men likely formed households with indigenous women. These women deeply influenced the foodways of their Egyptian partners and the foodways and other cultural practices of their Egypto-Nubian descendants. Smith uncovered unambiguous evidence for such intermarriages (or at least entanglements) at Tombos, where women buried according to Kerman traditions shared space in tombs with men and women buried according to Egyptian traditions.

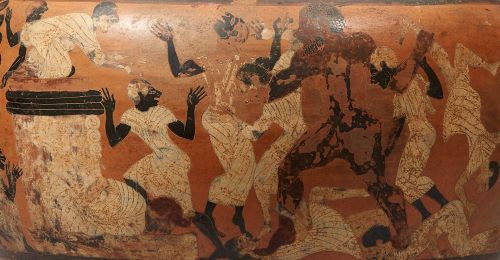

Race via Artistic Representations

Many ancient cultures took a seemingly “ethnographic” interest in representing the foreign peoples they encountered in war or through more peaceful interactions. While such depictions appear to offer a beguilingly easy method to access the way ancient people looked, representations of cultural others almost always conform to stereotypes that are intended to render them recognizable and also, often, to feed into the cultural chauvinism of the viewer. Even self-representations, however, can be problematic, as gender, class, and other identifying markers were clearly broadcast to internal audiences through skin color, hairstyle, and costume. These caveats aside, artistic representations of people in the distant past offer valuable clues as to etic and emic understandings of racial and ethnic difference.

Jennifer Gates-Foster explores the interactions between ethnic identities and imperial government in the case of the Achaemenid Empire. She looks to the art of the Achaemenid empire and its incorporation of artistic customs and depictions of conquered peoples. The portrayals of different ethnic groups under Achaemenid control were central to the empire’s ideology, as they created a visual representation of the diversity and expanse of the state. Similarly, she indicates that Achaemenid kings gradually incorporated more art forms and iconographic motifs derived from the art of conquered groups to again emphasize the power of the king and the empire. Gates-Foster points out, however, that the interactions between the empire and ethnic groups in the satrapies was much more complicated, and the relationship between the two as displayed in art remains unclear. Gates-Foster’s approach to this work thus provides a useful lens for viewing state perceptions of ethnicity, not local perceptions.

Ferris – continuing his previous analysis of the ‘barbarian’ character in ancient art – contrasts the Ludovisi Gaul by Epigonus (a Greek sculpture that had to be recreated in Rome) and a gilt diptych of the semi-barbarian general Stilicho at the Monza Cathedral Treasury. He does so in order to determine how these works provide insight into the social and cultural mindset of the creators and audience of their times. Where the Ludovisi Gauls sculpture depicts a nude man of great force and motion – “his body [as] wild power personified” – the sculpture of the Romano-Vandal Stilicho, possibly self-commissioned, has a static figure and stoic face.

Additionally, the woman displayed in the Ludovisi Gauls is described as limp and lifeless (forever infertile), whereas Stilicho is portrayed with both his wife Serena and his son. Working within the framework of colonial discourse, Ferris finds that to some degree works of art like these serve to exoticize and create a sense of nostalgia for the strength and pure primitivism of the ‘barbarian,’ but also this stereotype is in direct opposition to the ideal character of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Ferris’ work is an excellent example of how approaches through art history can shed let on how author or artist perspectives shape these stock characters of the ancient world.

Race via Critical Race Theory

A school of thought pioneered by Black scholars in the mid 1980s, Critical Race Theory (CRT) transformed the reading of literature, history, law, and nearly every other facet of the academy by suggesting that race, especially white supremacy, permeates the fiber of the world. CRT is a framework that can be widely applied and serves to question the fundamental assumptions of the scholarship and knowledge production through the complication of racial(ized) thought. Of the following sources Omi and Winant serve as an introduction to the topic, while other sources provide examples of how CRT can be utilized in classical research or suggest innovations to the framework itself.

Understanding race and ethnicity in the ancient world does not necessarily require experts on antiquity to give meaning, context, and important intervention to the texts and materials considered. Michael Omi and Howard Winant are sociologists concerned with America in the modern era, yet their construction of racial formation theory is a valuable model for thinking through ancient contexts. Most importantly, Omi and Winant challenge common notions of race as fixed and codified, proposing instead an idea of race as unstable, dynamic, and adaptive to its milieu – especially in the context of political and social conflicts. This theory is laid out primarily in chapter 4, “The Theory of Racial Formation,” which helpfully defines and complicates the terms race, racialization, and racialized. Racial Formation in the United States stands out in the bibliography of any student of Classics or ancient studies, as it gives an insightful and timely “outsiders” take on the matters at hand.

Haley, a Black woman and scholar of Latin poetry, masterfully explores how the two often isolated fields of Classics and Critical Race Studies can be meaningfully and revealingly placed into dialogue. Moving through some of the best known Latin works – among them selections from Catullus and Vergil – Haley puts her own translations alongside well known alternatives in order to demonstrate the power of taking a common Latin adjective instead as a racial descriptor. This work is especially useful to readers of Latin, for whom the text demonstrates how race and racial thought are encoded in poems that are often taken as race-neutral.

In her studies of “the afterlife of slavery,” Saidiya Hartman has forged new ground in interpreting Atlantic slave trade documents and in archival studies more generally. “Venus in Two Acts” is Hartman’s attempt to solve the mystery of Venus’ abundance and meaning for enslaved women in the Caribbean. Reading the diaries of Thomas Thistlewood – a cruel and perverse slavemaster who primarily wrote in Latin – Hartman demonstrates the violence of archives that serve to silence Black slaves. Aside from its overt connections to antiquity, “Venus in Two Acts” is essential reading for the student of CRT for its discussion of critical fabulation. In Hartman’s own words, “The intention [of critical fabulation] isn’t anything as miraculous as recovering the lives of the enslaved or redeeming the dead, but rather laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible. This double gesture can be described as straining against the limits of the archive to write a cultural history of the captive, and, at the same time, enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration.” This tool, widely and keenly applicable to the Classical canon, which is often marked more by its silence than its voice, will enhance the theoretical approach taken by any scholar.

Speaking at a panel on Race and Periodization, literary theorist Margo Hendricks called for the abandonment of Premodern Race Studies – something she sees regularly and unproductively performed in academic settings – in favor of Premodern Critical Race Studies. The impact of the word “critical” here adds an important valence, one that pushes against the white academic seizure of Premodern Race Studies. Premodern Critical Race Studies, Hendricks notes, “actively pursues not only the study of race in the premodern, not only the way in which periods helped to define, demarcate, tear apart, and bring together the study of race in the premodern era, but the way that outcome, the way those studies can affect a transformation of the academy and its relationship to our world. [Premodern Critical Race Studies] is about being a public humanist. It’s about being an activist.” Clearly, the field of Critical Race and antiquity is still actively forming. Listening to the scholars who are currently pushing the boundaries of conceptualizing race in antiquity and reshaping these limits is vital.

Isaac never marks out his method as being in line with CRT – partly because his primary interest is in the development of antisemitism as a product of antiquity rather than anti-Blackness – but the text is placed here as it makes not just a claim of race, but of racism, which is explored through the lens of white supremacist values. In many ways, Isaac is the antithesis to Snowden in Before Color Prejudice (mentioned earlier in the bibliography), as he finds there to be a direct line of development between Greco-Roman supremacy and European white supremacy, which he substantiates in the reading of imperial texts. Isaac is one of the few scholars of Classics who suggests that racism is itself ancient, and this is a hypothesis, contested though it may be, that is worth unpacking and sitting with. The text will be particularly useful for students of Jewish history and those interested in the formation of genocidal thought and holocaust, but serves a broader function of forcing confrontation with racism itself.

In Race: Antiquity and its Legacy, McCoskey provides the most salient generalist’s overview to race and ethnicity in the ancient world. McCoskey’s thesis is that race in antiquity is distinct from the way race comes to function after the colonial era but that ancient ideas concerning race gave way and perhaps even gave power to more modern conceptions. While this notion might seem obvious, McCoskey’s text eruditely guides the reader through these ideas with accessible analogies. For example, she places the dichotomy of “Black versus white” in dialogue with the sense of “Greek versus Barbarian” in the post Persian War context. Race: Antiquity and its Legacy, while certainly not an anthology, provides numerous primary sources in a distilled and contextualized form, thereby granting its reader not only theory but also applicable further reading. This work is a necessary companion to any formal introduction of race and ethnicity in the ancient world.

In this article, Tristan Samuels confirms the existence of Blackness in ancient Egypt and reorients our understanding of the origins of anti-Blackness in Western thought. In examining the writings of Herodotus, Western scholars of the late 20th century actively engaged in the “denial of ancient Egypt’s Blackness” by acknowledging the “so-called Black features” of Egyptians (like hair texture or skin tone) described in ancient Greek writing, while also maintaining that the “ancient Egyptians could have been anything—but Black.” This erasure is the product of a white supremacist lens in Greco-Roman studies that “equates ‘Negro’ with inferiority and ugliness” but according to Samuels, this lens started before 20th century academia and even before the transatlantic slave-trade. Drawing on Herodotus 3.101, he argues that the Greek historian ‘othered’ the Black body, promoting ideas of the hypersexuality, savagery, and cowardice. Here, Samuels illustrates both the prevalence of Blackness in the Classical sphere and argues for the “antiquity of anti-Black racial prejudice” in Western thought.

Race via Ethnic Studies

The study of ethnicity has been a fashionable investigation far longer than race in Classical and ancient studies. This is in a large part because it is obvious that ancient peoples had strong notions of ethnicity, marking themselves out in clusters conjoined by common descent, linguistic affiliation, religion, and location. That being said, the longevity of the project of ethnic explication does not preclude the growth in the area which is ever-(re)forming in response to new discoveries. The following sources are rooted in various aspects of ethnic formation, and cover ethnic groups from many parts of the ancient world. The featured work of Jonathan Hall gives a well-wrought construction of ethnicity and is a good place to begin.

Hall’s Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity is an excellent introduction to various methodologies useful in approaching race and ethnicity in the Hellenistic world. The text’s primary utility is its inclusion of theoretical frames, with full definition relating the terms both to modern and ancient contexts. Hall views ethnicity in the ancient world as operating in an instrumental sense, which is to say that ancestral, mythological, and even genetic linkages are cultivated in a group’s pursuit of political and economic power. The instrumental view, and Hall’s definition of the ethnic group itself, is largely formed in chapter 2, “The nature and expression of ethnicity: an anthropological view.” Hall outlines his primary stakes in the argument, which he applies in later chapters to other areas – among them archaeology and linguistics. Moreover, Hall tests his own theories of race and ethnicity in antiquity alongside those of other scholars, so the text itself provides a decent intellectual history. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity is a wonderful resource for anyone looking to find footing in the vast scope of ancient ethnic studies, and it leaves its reader with a robust vocabulary and theoretical foundation in approaching these arguments in primary sources.

Allen-Hornblower acknowledges that the veracity of Herodotus’ accounts leaves much to be desired; however, she argues in this piece that while the factual reliability of Histories remains questionable, the way in which Herodotus depicts displays of emotion (whether real or imagined) reveals an under-explored methodology of discussing how ancient peoples viewed other ethnic groups. Importantly, emotional responses (and how they are perceived by others) betray a society’s values and form how they interact with and understand the actions of other groups. Perceived emotional responses (whether genuine or not) to events that befall another group, for example, warfare or famine, can indicate how two separate entities perceived their relation to one another, both along ethnic and political bounds. Allen-Hornblower analyzes how the emotions of fear, anger, pity, and grief are depicted in Histories, offering valuable insight as to how emotion can act as a gateway between ethnic groups.

Ethnicity is conditioned by several factors: geography, ancestry, language, and importantly, religion. The rise of Christianity from a fringe religious movement to the central dominating and binding identity of the Roman Empire was not a swift nor even a fully understood transition but one that is pertinent to any examination of ethnic mutability and mobility in antiquity. Peter Brown’s lecture explains Christianisation as a multifaceted and often decentralized project, noting, “I have long suspected that accounts of the Christianisation of the Roman world are at their most misleading when they speak of that process as if it were a single entity, capable of a single comprehensive description that, in turn, implies the possibility of a single, all-embracing explanation.” In his view, ethnic alteration was nuanced and imbalanced, yet focalized and meaningful. This selection from the Tanner Lectures series is an accessible and thorough beginning to one’s study of Christian identity.

The dawn of the Roman Empire brought about massive shifts in the ethnic composition of the ancient Mediterranean. With its expansion over vast tracts of the Near East, North Africa, and Europe, the formulation of a coherent “Roman” identity was a necessary, critical, and ever-tenuous project. Regulating concepts of identity in Rome, Dench argues, involved a strict and decisive imperial effort that drastically impacted epistemologies of self, empire, and citizenship. In tracing the foundation mythology of Romulus and Remus through its living history, Dench is able to analyze changing judicial, mythological, imperial, and familial notions of belonging to Rome, lending her project an impressive scope. Among the most important of Dench’s interventions is her suggestion that Roman identity was “virtual” (i.e. geographically diffuse and shifting) – a helpful framework for approaching various instances of ethnic formation in the ancient world.

Language functions as one of the most obvious signifiers group identity. For example, Athenians referred to ‘others’ as Barbarians based on their inability to speak Greek. Language is not, however, necessarily fundamental to a group’s identity. In “Ethnicity and Language in the Ancient Mediterranean,” Haarmann sees ethnic identities as dynamic – with languages and other salient markers changing naturally over time and through interaction with others. Migration and conquest often spread both culture and language, as countless studies of Indo-European population movements attest, but in such encounters cultural influence went both ways, resulting in transculturation. In the Roman Empire, as Haarmann notes, Latin changed significantly due to the linguistic assimilation of Etruscan words and nomenclature.

Harland explores the strategies three Judean authors—Philo, Paul, and Josephus—used to navigate Greek and Roman ethnic hierarchies, respective to their social and political climate. Philo of Alexandria, for instance, lived during a time of peak ethnic tension between Greeks, Egyptians, and Judeans and thus resorted to aligning Judeans with Greeks by playing into stereotypes of “inferior, seditious Egyptians and superior, loyal Judeans.” Josephus, on the other hand, altered Judean proximity to Greekness depending on rhetorical effect. Like Philo, he brought Judeans closer to Greekness by distancing Judeans from “low-down” Egyptians, but also distanced Judeans from Greekness when characterizing Greek culture as “new and therefore inferior.” Finally, Paul avoided playing into the established ethnic hierarchy at all and created “an alternative to the hegemonic ladder” that placed Judeans at the very top and that tended to “clump together all non-Israelite peoples” in a way that blurred specific ethnic distinctions. These strategies, though each unique and distinct, overlapped in their reliance on the way “othering” stereotypes “generate an ethnic hierarchy.”

Herodotus’ Histories is well known among classical historians for its titillating, albeit at times inaccurate, accounts of ancient history. In his essay, Brian Hill explores Herodotus’ usage of the Greek word ethnos in his Histories. Hill extracts Herodotus’ definition of ethnos through close analysis of several short passages from the Histories, as he attempts to determine what constitutes an ethnic group from Herodotus’ perspective (as opposed to what constitutes a group that is merely a part of a larger ethnic entity, and as such is not designated by Herodotus to be a separate ethnos). In doing so, Hill offers readers a more nuanced understanding of the word ethnos as it is used in Herodotus’ accounts. This source is particularly useful for those who read Greek, as it explicates the complex connotations of ethnos in ancient Greek literature.

The title of this chapter is a bit misleading, as Ingram does not discuss ‘teenage rebellion’ at all. Instead, she provides an overview of Nubian scarification and tattooing, explaining how they would have been done and the purposes they may have served. This is relevant to the concept of a Nubian ethnic identity both because these body modifications communicated important affiliations and cultural messages internally and because they influenced outgroup perceptions of Nubian identity. Egyptian literature and art include scarification as an important trait in identifying (or disguising oneself as) a Nubian. Additionally, because tattooing was practiced primarily women and because similar tattoos in Egypt are witnessed on priestesses and cultic dancers, Ingram suggests that the bodily modifications may have been undertaken as fertility magic. Scarification, however, is thought to have had a medicinal aspect to its use, which would explain why it is far more common (and unisex) than tattooing.

Miller’s article (the first in a series) examines the scholarly conversation around the Greek word ‘Ioudaios’ in early Christian literature, which is often translated as ‘Jew’ or ‘Judean.’ This work serves as a case study for the complications involved with translating ancient labels into modern language. By looking at how the term is used differently in various sources and the studies of various scholars, Miller concludes that when the word was in use, ‘Ioudaios’ was employed by outsiders to describe the group, while ‘Israel’ was the term used by the people to describe themselves. After establishing who used the term and in what context, Miller moves on to uncover the meaning of the term by comparing it to how other groups were labelled at the time – such as by nationality, religious and ethnic affiliation, the latter of which might be separate from or dependent on other factors such as geography. This article would be particularly useful to people interested in the etic and emic resonances of ethnic nomenclature as well as people interested on the socio-historical implications of language.

Building from Edith Hall’s theories in Inventing the Barbarian, Thompson examines two works by the Roman authors Julius Caesar and Tacitus that speak of the German ‘barbaric other.’ Thompson argues that these texts are more representative of Roman self-perception and society than they are historical accounts of Roman Germania and its people. Julius Caesar’s work addresses the Roman aristocratic male and is composed of his own military accounts from the Gallic wars, supplemented by ethnographies. However, Thompson claims that Caesar’s purpose is to “construct an ethnocentric worldview that fits his colonist ambitions.” Here, the German barbarian ‘other’ serves as justification for imperialism. Meanwhile Tacitus’ work – written in the heat of the Roman imperium – has anti-imperialist undertones as it creates the character of the ‘noble savage.’ Thompson demonstrates that in tying the German political system to Republican Roman ideals, Tacitus can undermine Imperial Rome. Overall, Thompson’s work is important in both understanding how ancient authors can manipulate the ‘other’ or barbarian to suit their own political agenda within a text and also in how we ought to be wary of accepting ethnographies embedded in texts like these as representative of peripheral societies.

Race via Geography and Environmental Theory

A thought that often emerges in approaching race in the ancient world is that race might not have existed but homeland-based discrimination did. The reason for this is that the barbarian – that uncivilized, hated being – was by definition a person born in the non-Greek world. The following works attempt to explain how geographies and historiographies that detail space contribute to a salient construction of the foreigner and the qualities which they embody. They also attempt to come to terms with cartography and topological imaginations.

Conceptual geography was not only an important facet of relationships between ethnic groups, but connections to specific places often helped, literally and metaphorically, to define a people’s orientation. Specifically examining this intimate relationship in the context of Judaism and Jewish intellectual history, Ben-Eliyahu’s work explores spatial awareness in post-Biblical antiquity. While the work does little to contextualize the project of Jewish homeland studies in the modern era, it is a largely insightful examination of how ethnicity and religious cohesion is predicated on histories of self that are bound to changing landscapes and notions of the “Holy Land.” Specifically exploring such changes in the Age of Hadrian, Ben-Eliyahu lends both theories of intimacy and place alongside well-formed historiographical work to the study of Judaism in antiquity.

The Hippocratic Corpus offers insight into ancient notions of race and ethnicity by virtue of its expansive categorization of various geographically disparate groups. While not all produced by Hippocrates, the Corpus is bound by a common notion of environmental determinism, asserting that the specific characteristics, temperaments, and physicalities of a population are largely due to the location from which they hail. Calame, in this chapter from his book Masks of Authority, explores the pseudoscientific racism that underlies Hippocrates’ project as well as more modern adoptions of the Hippocratic ethic. Serving as a thorough introduction to many aspects of Hippocrates and his legacy, Calame should be read by those who hope to glean more insight to geography as the foundational constructor of racialized hierarchies.

Mono-chromatic differentiation, that is racial and ethnic demarcations which exist between groups of the same skin-color, contributes to a substantial portion of all racialized encounters in the ancient world. One set of interrelations that illustrates this phenomenon took place between the Romans and the Celts, the inhabitants of the British Isles during the 1st century CE, who were conquered under the Roman general Agricola. Katherine Clarke’s close reading of Tacitus’ Agricola constitutes an important intervention in environmental studies, as she demonstrates how Britain’s geographic otherness and isolation made it, for Tacitus and his countrymen, a natural and elusive foe. Clarke’s work is bolstered by a vast array of ancient sources and makes valuable contributions to island theory – the examination of how islands manifest in human history and imagination.

Though this work could easily belong in the section on ethnicity, the most interesting reading Nippel presents is that of topoi as “commonplaces” which creates a topological throughline in this chapter. Nippel’s primary interest is how, if Barbarian marks out a shifting position of relative non-Greekness, the spatial realm of the Barbarian is altered. The piece is dense with the names of ethnic groups, tribes, and polities most of whom are pulled from Herodotus and Xenophon, but its real strength lies in its close analysis of the terminologies of differentiation. Readings of topoi as they pertain to Greeks and Romans, the latter being a once barbarous group, are particularly interesting and frames these tensions of identity as tensions of boundary and empire. Nippel makes a curious move in the last pages of the chapter, shifting to think about the Medieval and early-modern eras and considering how topoi and otherness are picked by the European empires successive of the Greeks as a pattern of translatio imperii, transfer of power, marked out in historiographical literature.

Race via Intermarriage, Citizenship, and Legal Regulation

In situations of interethnic contact there existed no greater threat to group identity than intermarriage. Although intermarriage could be strategic – or even necessary – in certain circumstances, it often became subject to strict social or legal sanction by those eager to preserve the status quo. Such concerns often shaped legal and fiscal policy. Yet the bicultural products of such intermarriages frequently grew numerous enough that they served as the basis for a new culture that creatively combined different aspects of previously distinct cultural heritages.

Alan L. Boegehold explores the motivating factors behind an Athenian law which limited Athenian citizenship to “men born of two Athenians.” Boegehold notes that the Greek philosopher Aristotle explained this law as a way to reduce the already large body of citizens; he argues, however, that this does not explain the motivations for limiting the population of citizens. Boegehold tackles this issue by first exploring the perks of citizenship, such as protections against torture and arrest, the ability to hold office, and the right to own and inherit property. This last perk is the most important to Boegehold, given the limited amount of land in Attika, the region surrounding Athens. He argues that previous laws of citizenship were unclear, leading to many legal disputes and subdivisions of land. Thus, Perikles’ redefinition of citizenship was motivated by a desire to limit the population, as Aristotle said, so as to ameliorate these recurring problems. Boegehold’s chapter therefore offers an example of how economic and political factors influence the legal definitions of ethnicity.

Kennedy seeks to redefine the experience of metic, or foreign-born, women in classical Athens by closely examining the laws and practices instituted to either prevent or aid in their assimilation into Athenian society. In particular, Kennedy discusses the implications of the 451 BCE Periklean Citizenship Law on the experiences of metic women in Athens, exploring how the law affected their ability to intermarry, bear legitimate children, and engage meaningfully with Athenian society. Kennedy demonstrates that a metic woman’s ability to claim Athenian citizenship fluctuated with the stability of the state and could expand or contract accordingly. By tracking the evolution of the Citizenship Law, from its conception through several of its adaptations, Kennedy successfully explicates social statuses that could be achieved by immigrant women in Athens. This text is useful for those who are interested in the intersection of gender, class, and ethnic identities in ancient Greece.

This text looks at the intermarriage ‘crises’ written about in the ancient Jewish books of Ezra and Nehemiah regarding ethnic identity and the importance or lack thereof of language in the context of Jewish identity. Southwood explores the idea of language as a part of ethnicity in many different ways including as a tool for boundary maintenance, part of political identity, and as a symbol. Grounding the text on issues of intermarriage allows language to be seen as a factor that threatens ethnic boundaries, seeing as they can be so easily threatened by bilingualism. Although Southwood does not provide much background or contexts for Ezra and Nehemiah’s literature, this text is useful in the theoretical sense for looking at strategies of group preservation from authorities in the ancient world as well as exploring ideas that transcend specific circumstances such as intermarriage.

Race via Reception in Literature

Artists across the world have long mobilized Greco-Roman literature as a prompt to reimagine, articulate, and imbue with recognized universal value stories pertinent to their own cultural experience. For authors interested anti- and post-colonial literatures, reframing classical myths and narratives has likewise allowed them, in the words of Emily Greenfield, “to mediate and represent subaltern conditions and experience and to give them wider currency.” Their works – whether set in the Caribbean or in the American South or in some other highly racialized sphere –subvert any sense that the lives of those who struggle under and against white supremacy are not epic, tragic, or worthy of song.

The Middle Passage was the leg of the triangular trade wherein African slaves were moved to plantations in America, usually carried on European boats. Emily Greenwood selects two representations of the voyage – Walcott’s Omeros and NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! – and uses them as points of mediation: first as “classical myths and/or texts that serve to mediate and disseminate Black Atlantic experience,” and second as “tempering or reconciling received ideas of classical texts.” Unlayering the Greco-Roman epic tradition, which pervades the motivations and aesthetics within both works, Greenwood demonstrates how both Walcott and NourbeSe Philip mobilize Latin in a production of reorienting and dismembering structures of power.

The first paragraph alone of Toni Morrison’s 1988 Tanner Lecture on Human Values is enough to exercise one’s brain and suspend typical expectations of language. Morrison, most broadly, seeks to locate African-Americanness in a canon it has long been present, yet unacknowledged, in. A student of Greek at Howard, Morrison’s works are imbued with resonances of – and clear departures from – ancient mythology. Morrison is especially interested in how canons are constructed and in the processes of legitimation, inclusion, and flattening. As she puts it, “The subliminal, the underground life of a novel, is the area most likely to link arms with the reader and facilitate making it one’s own.” Morrison provides an excellent entry to Classical reception, as she frequently mentions both Classical works and the scholars who unpack them (Bernal makes an important appearance). Yet she also moves beyond what the Classical canon is to discuss what it has become and, powerfully, what it can mean.

For more information on the Classical threads woven within Morrison’s works, see Justine McConnell’s Postcolonial Sparagmos: Toni Morrison’s Sula and Wole Soyinka’s The Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite, which also draws attention to Soyinka’s translation of the Bacchae (undertaken while he was political refugee in London). Tessa Royon’s “The Africanness of Classicism in the Work of Toni Morrison” published in African Athena: New Agendas, also explores the entanglements and tensions between Morrison and the Classics.

Through the examination of a single Du Bois novel, The Quest of the Silver Fleece, Jackie Murray attempts to demonstrate a Classically informed and compelled character using biographical analysis and literary examination. Murray uses The Quest of the Silver Fleece to meditate on Du Bois’ beliefs on higher education and political representation, especially through the myth of Medea and Jason. The text is well paired with Rankine’s “Classics for All” chapter, as both discuss Black access to Classical pedagogies and the motivations behind this education. Moreover, Murray receives not only Du Bois’ the Souls of Black Folks but also the Argonautica of Apollonius. The cooperative reading lends new meaning to both texts and binds them to a larger conversation about the Classical education of Black America.

Heroism and the idiom of the Classical hero extant in the art, aesthetic, and experience of Black Americans is the central exploration Rankine presents in Ulysses in Black. Through tracing the “journey” of the hero, outlined in the first part as the journey “From Eurocentrism to Black Classicism”, and the second part as “Ralph Ellison’s Black American Ulysses”, the book presents a rich catalogue of Black experiences of the Classical canon and by this presents Classics as one mechanism of the formation of Black American identity. Though the text is essentially an exploration of reception, on account of his crafting Ralph Ellison as the emblematic creator in the Black Classical tradition, the work is perhaps best situated in literary and performance studies as a close reading of Invisible Man and Juneteenth demonstrates how to read Classical presence out of Black literature rather than into it. (ALR, 2021)

One of the most important texts discussed in Ulysses in Black, though briefly, is Countée Cullen’s Medea and Other Poems (1935), a collection which recasts Euripides’ Medea alongside several other characters from the Classical canon which is further discussed in Lillian Courti’s “Countée Cullen’s Medea” in African American Review (1998). For more treatment of Black American Classical theatre traditions, receptions, and productions, Kevin Westmore’s collections Black Dionysus: Greek Tragedy and African American Theatre (2010) and Black Medea: Adaptations in Modern Plays (2013) are good places to look.

Salvage the Bones is a novel by author Jesmyn Ward, published in 2011, that follows a Black American working-class family living in Mississippi and dealing with the events and aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The narrator, Esch, finds that the mythical story of Medea resonates with parts of her life. In an interview with the Paris Review, Ward says of Esch’s attachment to the myth, “it infuriates me that the work of white American writers can be universal and lay claim to classic texts, while black and female authors are ghetto-ized as ‘other.’ I wanted to align Esch with that classic text, with the universal figure of Medea, the antihero, to claim that tradition as part of my Western literary heritage.” Ward expertly draws on the universal themes of family, infidelity, and motherhood by placing the classic legend of Medea in direct dialogue with the story of a Black teenage girl in the 21st century American South.

Race via Reception in Performance Traditions

Embrace of racial conversation in Classical scholarship likely happened first not in the pages of some journal but on the Greek stage, which since pre-modern times has had to confront the racialized implications of various dramas and texts. The many sources in this category will lead you towards several digitized performances of ancient plays as well as their modern reimaginings. Some are tragedies that were directed and set in the Global South, while others were performed within the racial subtext in the West. All lend tools to read, and read critically, literary texts and performances produced in antiquity.

Luis Alfaro, a Chicano playwright from East Los Angeles, first adapted Greek Tragedy set to the tune of Latinx struggle with his Electricidad, a 2003 rendition of Sophocles’ Electra about vengeance and paternal piety in the Cholo Gang. In 2010 he followed the Sophoclean trend directing Oedipus El Rey, a play about prison gangs, and in 2015 Alfaro put out Mojada – a take on Medea about an undocumented mother traversing the Mexican-American border with her children. Alfaro’s Chicano Greek trilogy is a harsh reenvisioning of the originals, putting pressure on the theme of exile to consider incarceration and on the theme of familial duty to consider gangs. All three plays can be found for free through the Center Theatre Group and additionally have regular runs in New York City theaters.

On August 9, 2014, Michael Brown’s body lay exposed on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri for hours after his murder. The gathering crowd, aware that a white police officer had shot the young Black man in the back, several times over, set up a candlelight vigil as they witnessed the state-sanctioned effort to cover up and justify his homicide. The Greek stage provided the (male) citizens of Athens a space to witness great performances of violence and process these communally. Some echoes of that ancient tradition were reborn in 2016 when, in the auditorium of Normandy High School, from which Michael Brown had graduated just eight days prior to his death, Theatre of War productions staged Antigone in Ferguson. The play diverges little from the plot and dialogue of Antigone, but in the context of the shameful exposure of Brown’s body and the fissure this political decision caused in the city of Ferguson, the Sophoclean tragedy took on entirely new meaning. Accompanied with a gospel choir composed of members of the Ferguson community, the production is an ambitious and moving project of healing through art and community. The play is performed frequently, for free, across the United States, and online recordings can be accessed through the Theatre of War’s website.

Agostinho Olavo’s Além do Rio (Medea) premiered on stage in Rio in 1961, leaving unfortunately little record of its original production. Its legacy, upon which dos Santos builds his argument, however, is resonant in Brazilian theatrical traditions. Olavo’s Medea was potentially as transgressive to the norms of 1960s Brazil as the original Euripides was to his own Athenian audience, with Olavo adapting the story to reflect the legacy of African slave trade in Brazil and the social conflicts brought on by the presence of blackness in the nation. Olavo’s rendition is acutely critical of the nation state, and Brazil’s purported “racial democracy,” which in the 20th century was used to describe an unrealistic but supposedly realized state of absolute social mobility and racial equality. Além do Rio is complex and requires reading on 1960s Brazil to appreciate more fully, but it is nonetheless foundational to South American Classical receptions and performance traditions. (ALR, 2020)

For more information on Olavo’s Além do Rio, readers should consult Maria Cecilia de Miranda’s Five Medea’s in Brazil in the Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, which places Olavo in important context with other Brazilian receptions of Medea, as well as introducing rare photographs of these performances. In addition, readers more broadly interested in Brazilian adaptations of Greek tragedy should reference the work of Jorge Andre, who is extensively covered in the Latin American Theatre Review.

Exploring six productions of Greek tragedy taken up by Black artists in non-European contexts, Goff and Simpson introduce the reader to performances – and the traditions born from them – of Classical drama that are intentionally racialized and necessarily transgressive. These six performances are, Ola Rotimi’s The Gods Are Not To Blame, Rita Dove’s The Darker Face of the Earth, Lee Breuer’s Gospel at Colonus, Kamau Brathwaite’s Odale’s Choice, Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona’s The Island, and Femi Osofisan’s Tegonni. Most of these performances are inspired by the tales of Oedipus and Antigone, and Goff and Simpson go to great lengths to understand the importance of these two figures in the lifespan of African drama. The result is an in depth and sharp analysis of the Theban cycle and the latent racial hierarchy within it, a hierarchy that is suggested to be highly translatable to the African context. In addition, the collection aims to shift readings in Classical theatre away from psychoanalytic interpretations and instead focalize postcolonial theorists, especially Frantz Fanon, making the text a valuable addition to any syllabus.

Since Edith Hall’s publication of Inventing the Barbarian in 1989, the idea that Panhellenic Greek identity was forged in response to the Greco-Persian War(s) has been well-trodden. Regardless of the extent to which Hall’s hypothesis is accepted, there is surely truth that engagement with the Persians forced Greek consideration of self-definition, an undertaking that required political and literary pressure. Aeschylus’ The Persians was performed first in 472 BC, soon after the end of the decade long battle which ended in Achaemenid defeat. Since then, the play – which depicts the demise of hubristic Xerxes, attended by his widowed mother and ghost father – has been emblematic of the violence between “The West” and “The East.” Hall’s chapter in her collection Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium, traces the production history of The Persians, with focus given to those productions of it that followed the Gulf War and American intervention in the Middle East, as well as performances that happened outside of the western hemisphere. Hall’s work illustrates the value of tracking various forms of a production through different eras, regions, and contexts, and synthesizes around the notion that an inherent hatred for the East is produced by and contained in The Persians.

Though this edited volume uses the frame of post-colonialism as a temporal rather than discursive marker, this collection remains one of the most expansive collections on the non-Western productions and performances of Classics voiced through multiform methods and cultural traditions. Published in 2007, and based primarily off of discussions in the afterlife of a 2004 conference on “Classics in the Post-Colonial World,” there is an eerie quality as the text is forward looking and discusses the future of Classics, a future that at this point remains unrealized, yet helps contextualize the intellectual movement towards “non-traditional” Classics and demonstrates a clear ethic of discipline and disciplinarian culture.

Diaspora is an important lens through which to examine receptions and structures of Classicism. Classicisms in the Black Atlantic, which has several other chapters featured in this bibliography, is a collection that examines the theatrical and artistic productions of one particular diaspora, the Black Caribbean, and explores Classical reverberations in slave tradings, rebellions, and settlements in the New World. Adam Lecznar’s examination of Martinican author Aimé Césaire’s corpus uses the Classical philology of Nietzsche to reconsider certain structures within Césaire. Lecznar can be a little difficult to follow if you’re not fully familiar with theories of tragedy, tragic performance, and its reception, but his reading of Césaire is a valuable examination of race through literary reception. Moreover, Lecznar’s examination of the Nietzschean tension within the work of Césaire, itself inspired by and transcending Greek tragedy, brings various regions of reception to heads with each other.

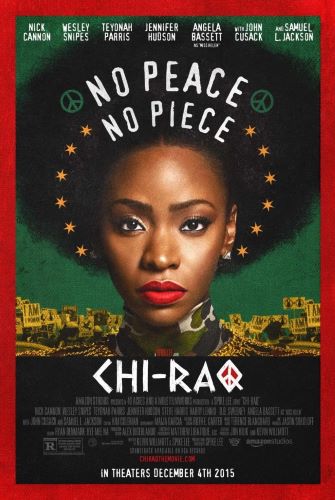

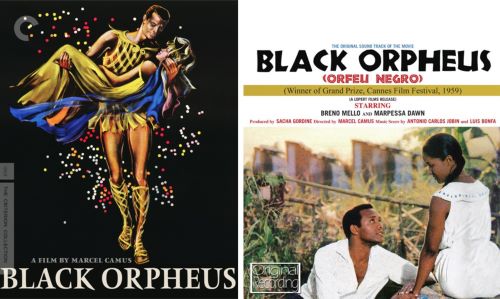

Chi-Raq is a 2015 feature film directed and produced by Spike Lee and co-written by Spike Lee and Kevin Willmott. It is a modern adaptation of the Aristophanes comedy Lysistrata set in the South Side of Chicago, where gang-related gun violence is prevalent. The premise of Aristophanes’ play is that a group of women threaten to withhold sex from their husbands in order to get them to stop the Peloponnesian war. In this adaptation, the girlfriends and wives of the members of two rival gangs do the same after a young girl is accidentally killed in a shooting as a plea to end the violence before another innocent member of the community gets hurt. The women in the film reference the pacifist activist Leymah Gbowee, a real person who led a women’s movement in Liberia to stop the nation’s Second Civil War. Threatening a sex strike was among the strategies the women employed (Mighty be our Powers, Gbowee, 2011). In the tradition of Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus, the film repurposes a story from classical Greco-Roman mythology in a Black, urban context.

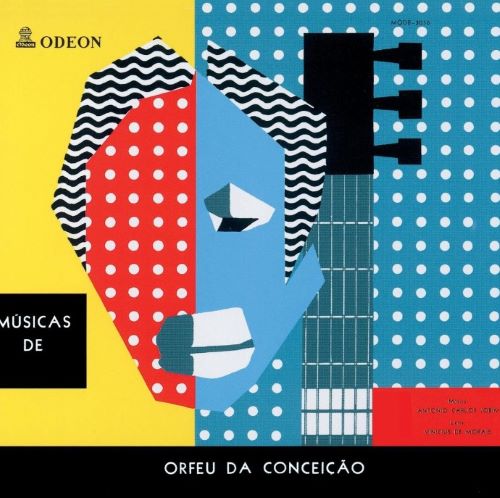

Orpheus of the Conception (Portuguese: Orfeu da Conceição) is a 1956 stage play in three acts written by the Brazilian playwright Vinícius de Moraes, with music by the Brazilian composer Antônio Carlos Jobim. The play follows the two lovers, Orfeu and Eurydice, through the tragic events of the classic myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, this time set in a favela in Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. At the beginning of the play, Moraes designates that all characters must be played by actors “da raça negra” (of the black race). The play was adapted into a feature-length film titled Black Orpheus (Portuguese: Orfeu Negro) by French director Marcel Camus in 1959 with a primarily Afro-Brazilian cast. The film opens with an image of a bas-relief sculpture in the classical style which shatters to reveal the Black residents of the favela dancing and playing music in celebration. In the same vein, both the film and the original play can be seen as deconstructing the whiteness and exclusivity of the classical canon.

The Aethiopica of Heliodorus, likely written in the 3rd century CE, tells the story of a Nubian King and Queen who produce a white-skinned daughter. Her mother, fearing the stigma of the child’s skin color, arranges for the child to be secreted away, and she is raised in Greece without knowledge of her royal ancestry or heritage. The antics which follow make Aethiopica a phenomenally fun read, as well a rich resource for discussions of race in antiquity. Incidentally, the text was repeatedly rediscovered, gaining new resonance in each context. Ndiaye Noémie, a scholar of identity formation through literature in the early modern era, explores the transmission of Aethiopica in France and the impact its stagings had on British theatre in the 17th century. Performing an ancient work whose stance on racial supremacy is obscure in a context where race and colonial expansion into Africa is a central motivating force imbued new meaning to the text and its reception.

Race via Reception in Nonfiction

The wide array of sources in this section will lead the reader to various receptions – intellectual, political, artistic, and cultural – and illustrate the multifaceted approach and form that reception as a method can take. The literature and philosophy of the Greeks and Romans became the foundation of educational curriculums in schools and universities worldwide. In colonial settings, Europeans hoped a classical education would prove useful in forestalling or avoiding revolutions. So, too, military leaders and politicians have long studied the imperial tactics and racial practices of Athenians and Romans for their own purposes. The cultural legacy of the classical world is neither inherently good nor bad, but people on nearly all ends of the social and political spectrum have found this legacy particularly useful to think with.

An artist whose primary medium is painting, Kimanthi Donkor examines representations of Andromeda – an Ethiopian princess, who was sentenced to be sacrificed to a sea monster as punishment for her mother’s hubristic vanity. Andromeda is eventually rescued by the hero Perseus. Donkor writes in an interesting and accessible fashion of his attempts while at the Tate Modern to discern Andromeda’s placement in the canon of Classical and classically influenced artwork. Specifically, he is concerned with the racial politics of her portrayal as Black or White. The piece is a wonderful exploration of a non-textual archive through the eyes of an artist.

Cleopatra VII is presented in duality; she is either a ruler or a homewrecker, a historical figure or a cinematic sensation, and, most recently, a Black woman or a white woman. Examining years of fierce historical debate, Mary Hamer questions the obsession with Cleopatra’s race (for an example of this see the Daily News article that the image is drawn from). She aims not to draw a definitive statement about her race, which many scholars have done in the past, but to instead explore the reasons why many are so concerned about assigning racial identity to Cleopatra in the first place, and what that fervent interest might say about racism in modern society and in ancient studies. In Hamer’s own words, “the demands of the movement have always determined Cleopatra’s image.” This article is an invaluable source for anyone interested in learning more about a ruler whose name has not only become commonplace in Western society but has also been utilized as an “argument… carried out among white people and the intellectuals who” have historically set “the terms of discussion.”

Green states that Bernal’s intentions in Black Athena to bring Jewish and African histories closer together – through positing an Afro-Asiaticism that underlies western civilization – ultimately fails. Using a framework of hybridity, however, Green offers a reading of Bernal that generates commonality between Jewish and African communities rather than discord. More than anything, Green is writing a piece of reception on one aspect of Bernal’s far stretching argument, namely that the unyielding divisions between Jewish and African communities can be traced through certain historical arcs to the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Classicists Margaret Malamud and Martha Malamud present a fascinating case study of two nineteenth century renditions of Cleopatra: one by William Wetmore Story, a white sculptor, and another by Edmonia Lewis, a Native American and African American sculptor. Story made the deliberate choice to give “African features” to his Cleopatra (1860), a drastic deviation “from classicizing portrayals of the queen” (it is important to note that this was received as an artistic choice and not as a statement of racial identity). On the other hand, Lewis chose to portray Cleopatra as white in The Death of Cleopatra (1876). This poignant article examines Lewis’s choice, which was perhaps established by her “encounters with white male artistic and literary fantasies of Cleopatra and her legendary sexual allure…” along with her “awareness of contemporary racist associations with excessive Black female sexuality.” With explorations of the ways racism functions even within Black representation, this is a relevant read for those who wish to learn more about the talented artist Edmonia Lewis and about race through artistic reception.

The Black Atlantic is a region marked out for its antiquity and for its trauma. Millions were dragged through its waters. These individuals would lose their families, homes, and freedoms only to become the foundation of the New World and all that would be built upon it. Classicisms in the Black Atlantic receives and responds to various traditions – literary, intellectual, philosophical – that emerged from the region, and it considers these in light of the Classical canon.

Rankine’s examination of issues of access and delimitation of thought in the post-Obama era lends itself to an important discussion of the point of Classics itself. Rankine notes that Classics for All, a campaign to give universal access to Greek and Latin language learning for school children, is problematized by “[its] idea of unidirectional mastery, namely that the recipients benefit from the discipline and leave it as pristine as they found it.” Rankine draws a meaningful analogy between the loss of particularity in approaching Classics and the Neoliberal flattening of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Victorian-era British scholars were forced to grapple with pederasty in ancient Greece and the moral dilemmas brought about by increasing contact with the “savage” and “sexually deviant” Orient due to British expansionism. The British blamed the Greeks’ pederastic behavior on Phoenician encounters in Crete (i.e., on non-white, non-European influence). This fed the “worrying prospect of ‘going native’” during British expeditions into Africa and Asia.” Just as the British could colonize the East with military might and exploitation, the British could be reverse-colonized by the East with moral depravity, impure sexuality, and effeminacy. Like their supposed racial ancestors, the Greeks, the British could suffer a “regression back into the Orient,” blurring the comfortably distinct racial lines between the East and the West. This line of reasoning also forced the British to reconsider the merits of a Classical education. Did Classical literature “civilize” or did it allow for the romanitization of its homoerotic, “uncivilizing” undertones? And more troublingly, were the Greeks secretly “savage”? And how much of that “savagery” did the British inherit?

As ubiquitous a text as it may be, Said’s Orientalism is worth revisiting, specifically as a work of Classical reception. Though his main interest is with the colonial movements which follow the Napoleonic Wars, Said, as an intellectual historian, places the foundational production of orientalism within the years following the Greco-Persian Wars. Further, Said puts an important tension on the dichotomies of East versus West, undoings which serve any project of ethnic and racial examination and certainly those of antiquity. Finally, Said’s seminal text is extraordinarily useful for its references and bibliography, as he culls together sources, historical moments, and artistic productions that are each worthy of exploration.

For more information on Said’s relevance within the field of Classics, consult Phiroze Vasunia’s article “Hellenism and Empire: Reading Edward Said“.

The Turkish nationalism that arose alongside Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who is considered the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, deliberately set itself apart from material and cultural markers of the deteriorated Ottoman Empire, instead focusing on emphasizing Turkish connections to ancient civilizations. In this article, Dr. Kenan Sharpe delves into the ways that two Turkish literary movements, New Hellenism and Blue Anatolia, sought to “establish a national mythology based in geography,” evoking the ancient histories of Anatolian civilizations such as the Hittites, Assyrians, and Trojans, which shared similar geographical spaces with Turkey. Dr. Sharpe argues that these literary movements also served as a ploy to incorporate Turkey into a broader Western European tradition based on classical heritage, and in doing so attempt to “challenge their neighbor Greece’s claim” to Hellenic civilization. This article is a fascinating example of the ways modern nations utilize ancient ethnic and cultural heritage (whether real or perceived) for both intranational and international relations and prestige.

The Classics in Colonial India were received first by the British colonizers, who were interested in conceptualizing their new domain and the people indigenous to it through the frames of the history and myth that appeared to support or motivate their imperial ideology. Shortly thereafter, however, it would be the colonized Indians who used Classics both to conceptualize the conditions and mechanisms of their colonization and to imagine a future that lay beyond it. These various receptions are central to Vasunia’s project, which considers representations of figures as central as Alexander (Sikhander) the Great and Gandhi. Vasunia’s use of both English and Indian archives, as well as his own familiarity with vernacular Indian traditions allows him access to intellectual traditions and sources not previously considered in the realm of Classics.

Race via Science and Technology

Reconstructing race is not just the project of the humanities but one driven by advancements in science and technology. From video games to genomic sequences, modern technology has enabled us to not just discern race through texts and artifacts but through methodologies and methods unavailable to previous generations of scholars. The following sources present a sampling of such projects and also the ethical issues we will contend with in their wake.

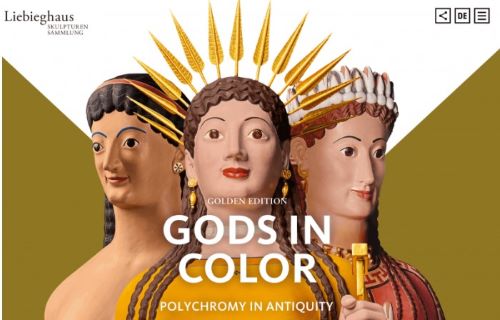

This remarkable online museum resource introduces individuals to the complexity of color and curation, unraveling the story of “white marble,” which historically was not at all white, but rather vividly bright. The curatorial staff at Liebieghaus are among a small but dedicated group of scholars attempting to reconstruct the original coloration of statues from the Greco-Roman world, which were purposefully white-washed for centuries in order to propagate a false notion of aesthetic purity. The Digitorial exhibit gives dozens of reconstructions, that serve to correct the incorrect belief that the Greeks and Romans fetishized white skin as beautiful and virtuous. Via their project, and by drawing attention to others of a similar vein, the Liebieghaus team argue persuasively that while the whitening of statues has usurped ancient conceptions of beauty, race, and self, technological advancements in restoration allow for a reversal of such usurpation.

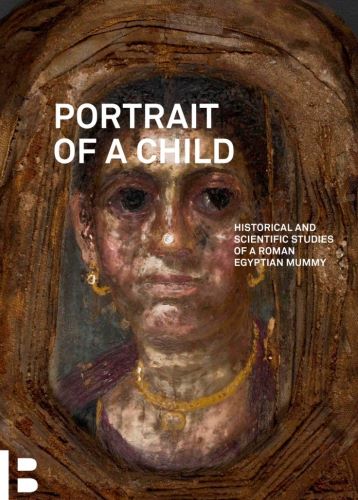

Forensic reconstruction in the past few years has largely focused its attention, rightly or wrongly, on Egypt. Perhaps this is due to the prevalence of physical remains or to questions regarding Egypt’s ethnic makeup in the Greco-Roman period, but through various projects we now have faces, races and even voices of ancient Egyptians. For example, a team at the Institute of Pathology in München, Germany led by Andreas Nerlich, used CT technology to examine the body of a young child and to create a facial reconstruction. That reconstruction was then compared with the funerary portrait incorporated into its mummy wrappings. The portrait was found to be reasonably accurate, although the child was presented as if slightly older than he turned out to be. (ALR, 2020)

The ethical considerations that attend to such reconstructions are as valuable to consider as the reconstructions themselves. Jasmine Day’s “Thinking Makes it So: Reflections on the Ethics of Displaying Egyptian Mummies” and Gareth Jones and Maja Whitaker’s “The Contested Realm of Displaying Dead Bodies” are two examples of such ethically-minded meditations. For more specific readings on reconstructional debates, Kenneth C. Nystrom’s “History of Bioarchaeology and Mummy Studies” and Bettina Lonfat and Ina Kaufman’s “A Code of Ethics for Evidence‐Based Research With Ancient Human Remains” lend important insight.

When approaching the issue of race in the ancient world, it is difficult to avoid preconceived notions of how these people looked, acted, and moved through their worlds. Often these logics are informed by the depictions of ancient people and places in popular media. Video games are integral to the formation of this imagination, with one notable example being Assassin’s Creed. Depicting events from Ptolemaic Egypt and the Peloponnesian War, Assassin’s Creed invites players to partake in fundamental moments in world history. In his in-depth examination of Assassin’s Creed’s representational hierarchies, Hammar explores how the game presents “real” and “authentic” visualisations that are intentionally uncomplicated – thereby undermining historical trauma. Hammar argues that video games serve as procedural and performative methods of memory-making and thus should approach their historical subjects with more nuance and care.

Originally published by Classics & Ancient Studies, Barnard College, open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.