Federal courts, particularly the Supreme Court, are the final authority on interpreting federal law.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Article III, Section 1

The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause provides that the Constitution, federal statutes, and treaties shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

The Supremacy Clause thus presumes that state courts will interpret—and be bound by—federal law.

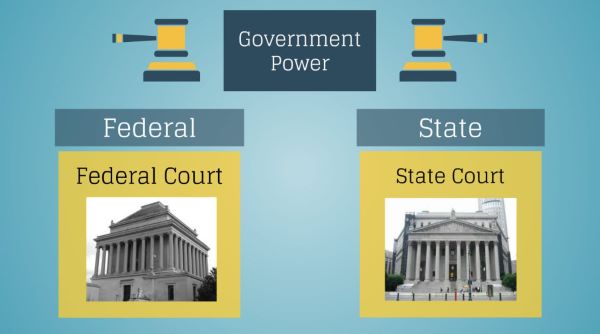

Under modern practice, both state and federal courts play an important role in interpreting and applying the Constitution and federal law. However, at the time of the Founding it was not initially clear how that power would be divided between federal and state courts.

In the years since the Founding, Supreme Court decisions have established that federal courts, particularly the Supreme Court, are the final authority on interpreting federal law, and federal courts possess the constitutional authority to review state court decisions that allegedly conflict with the Constitution or federal law. Various statutory and court-made rules govern when such review is available, however. In some circumstances, a complainant bringing a claim under federal law is required to exhaust available state legislative or administrative remedies before seeking relief in federal court; by contrast, exhaustion of state judicial remedies—for example, by first bringing related state law claims in state court—is not generally required. There are also circumstances in which the federal courts have the power to assert jurisdiction over a case but decline to do so out of respect for the sovereign authority of state courts.

As for state courts, they are generally authorized to hear claims involving federal law, except in areas where the federal courts possess exclusive jurisdiction. Moreover, subject to limited exceptions, state courts are usually required to hear cases arising under federal law over which they have jurisdiction. State courts generally lack the authority to enjoin proceedings in federal court or prevent the enforcement of federal court judgments.

Historical Background

At the time of the Founding, each state had its own system of courts, while the Articles of Confederation did not provide for an independent Federal Judiciary. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention agreed early on that the new Constitution should establish a federal Judicial Branch including a Supreme Court; however, they debated other questions about how to balance federal and state judicial power.

The Framers generally accepted that state courts would play a significant role in interpreting and applying federal law. However, some of the Framers also entertained concerns about whether state courts would apply federal law correctly, uniformly, and without bias. Then, as now, the specific structure of state courts varied significantly from state to state. State court judges often did not enjoy the safeguards that were afforded federal judges, such as life tenure during good behavior and salary protection. Certain delegates to the Constitutional Convention expressed concerns as to whether state court judges might therefore be subject to political pressures that could affect their decision-making. Others raised the prospect of disputes between states, noting that a state court might issue decisions that were biased in favor of its home state. Some Founders worried that the multiple state courts could interpret federal law differently, undermining the interest in having uniform federal laws.

To mitigate those concerns, the Framers provided for a federal Supreme Court with the power to review state judicial decisions involving issues of federal statutory or constitutional law. Debate arose, however, on the question of whether lower federal courts were also necessary. Some delegates argued that establishing lower federal courts would encroach on the power of the states. Some argued that a right of appeal from state court to a federal appellate court would suffice to ensure uniformity and prevent bias. Other delegates countered that a right to appeal would provide less effective protection of federal rights than the right to consideration by an impartial tribunal in the first instance. The Convention discussed whether creating lower federal courts would lessen the burden on the Supreme Court and prevent it from being overwhelmed by numerous appeals. Some delegates voiced an interest in flexibility, contending that lower federal courts might be needed in the future even if they were not immediately necessary.

Ultimately, the Framers left the decision of whether to create lower federal courts to Congress. Article III of the Constitution provides for one supreme Court, and . . . such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.

The first Congress exercised its authority promptly, creating lower federal courts in the Judiciary Act of 1798, the first legislation related to the Federal Judiciary.

Doctrine on Federal and State Courts

By specifying the extent of the judicial Power,

the Constitution authorized the creation of federal courts with limited subject matter jurisdiction. Article III identifies several categories of cases over which the Supreme Court possesses original jurisdiction. In addition, the Constitution generally authorizes federal courts to hear all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority,

as well as admiralty cases, cases between citizens of different states, and cases between citizens of a state and a foreign state or its citizens.

Within those broad categories, Congress has traditionally been understood to exercise significant discretion to decide which cases particular federal courts have jurisdiction to hear. The Constitution sets the maximum possible extent of federal court jurisdiction. Congress cannot expand such jurisdiction beyond the applicable constitutional limits, but is free to grant the federal courts authority over only a subset of constitutionally permissible cases. In practice, Congress has always granted the federal courts less expansive jurisdiction than the Constitution authorizes. The first Judiciary Act granted the federal courts exclusive jurisdiction over matters including federal criminal cases, admiralty cases, and certain cases involving seizures of property under federal law. The Act also granted the federal and state courts concurrent jurisdiction over other classes of cases, including certain tort suits brought by foreign nationals and common law suits brought by the United States government. Since that time, Congress has periodically expanded the scope of federal court jurisdiction, but has never provided for federal court jurisdiction in all possible cases that would be authorized under the Constitution’s jurisdictional limits.

In contrast to the federal system, the states operate courts of general jurisdiction, which are not subject to the constitutional jurisdictional limits placed on federal courts. As part of such general jurisdiction, state courts have concurrent jurisdiction to hear most cases that raise issues under the Constitution or federal law. Congress may enact legislation providing that certain claims arising under federal law may only be heard in federal court. However, unless Congress provides for exclusive federal court jurisdiction, a case raising federal law claims may proceed in either state or federal court.

If a plaintiff files in state court a case over which the federal courts could exercise jurisdiction, the defendant may elect to remove the case to federal court pursuant to federal statute. In addition, a party may seek Supreme Court review of a decision of a state’s highest court in cases where a state law, executive action, or judicial interpretation allegedly conflicts with the Constitution or a federal law or treaty.

As the following sections discuss in more detail, other interactions between federal and state courts may occur as cases move through the judicial system. For example, because the federal Constitution, statutes, and treaties are the the supreme Law of the Land,

and federal courts are the final authority on the interpretation of federal law, state courts applying federal law are bound by controlling decisions of the federal courts. Relatedly, federal courts may sometimes enjoin proceedings in state court, and federal courts can hear challenges to state criminal convictions pursuant to petitions for a writ of habeas corpus. By contrast, state courts have much more limited power to enjoin or otherwise affect federal proceedings. Nonetheless, as a matter of federal-state comity, federal courts will sometimes abstain from hearing cases raising novel questions of state law, and in some cases may require litigants to exhaust available remedies under state law before filing suit in federal court.

State Court Jurisdiction to Enforce Federal Law

Unless the federal courts possess exclusive jurisdiction over a matter, state courts may hear cases over which federal courts would have also had jurisdiction. However, it does not necessarily follow from the fact that state courts are authorized to hear claims arising under federal law that the state courts must agree to hear federal claims. In deciding multiple cases on this issue, the Supreme Court has ruled that state courts generally must hear federal law claims unless state law bars a state court from hearing a federal claim through a neutral rule of judicial administration

that does not improperly burden claims arising under federal law.

In the 1876 case Claflin v. Houseman, the Supreme Court held that state courts could hear cases arising under federal bankruptcy law. The Court reasoned:

The laws of the United States are laws in the several States, and just as much binding on the citizens and courts thereof as the State laws are. The United States is not a foreign sovereignty as regards the several States, but is a concurrent, and, within its jurisdiction, paramount sovereignty.

The Court thus held that the State courts have concurrent jurisdiction whenever, by their own constitution, they are competent to take it.

While Claflin concerned when state courts may exercise jurisdiction over federal claims, a number of subsequent cases have cited Claflin when considering when state courts may validly decline jurisdiction over federal claims.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has upheld state courts’ refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a valid excuse

to decline jurisdiction. For instance, in Douglas v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., the Court upheld a state law that allowed state courts to decline jurisdiction over both state and federal law claims when neither party was a resident of the State. The Supreme Court noted that there was nothing in the federal statute at issue that purports to force a duty

to hear cases on state courts as against an otherwise valid excuse.

In Howlett v. Rose, the Court summarized cases like Douglas, where states had validly declined to hear federal claims, as involving neutral rule[s] of judicial administration.

By contrast, in Mondou v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., a Connecticut court declined to hear a case arising under federal law, in part because the state court held it was at liberty to decline cognizance of actions to enforce rights arising under [the federal] act, because . . . the policy manifested by it is not in accord with the policy of the state.

The Supreme Court rejected that proposition and held that the state court must hear the case. In so holding, the Court emphasized that the case did not involve any attempt by Congress to enlarge or regulate the jurisdiction of state courts, or to control or affect their modes of procedure,

but only a question of when state courts must hear federal claims that fall within their ordinary jurisdiction, as prescribed by local laws.

Similarly, in Testa v. Katt, the Rhode Island Supreme Court declined to enforce a federal statute containing a punitive damages provision, finding that the law was penal in nature and the state need not enforce the penal laws of a government which is ‘foreign in the international sense.’

The U.S. Supreme Court reversed, holding that the Rhode Island court must enforce the federal statute, and that a state policy of not enforcing penal statutes of other sovereigns was not a valid excuse

under Douglas. Among other things, the Court explained that [i]t cannot be assumed, the supremacy clause considered, that the responsibilities of a state to enforce the laws of a sister state are identical with its responsibilities to enforce federal laws.

In the 2009 case Haywood v. Drown, the Supreme Court considered a state statute that divested New York state courts of jurisdiction over suits under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 seeking money damages from corrections officers, as well as similar state law claims against corrections officers. The Court held that the New York law violated the Supremacy Clause. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens explained, we have emphasized that only a neutral jurisdictional rule will be deemed a ‘valid excuse’ for departing from the default assumption

that state courts will hear federal claims. Although the New York statute removed jurisdiction over both state and federal claims, the Court held, equality of treatment

between state and federal claims does not ensure that a state law will be deemed . . . a valid excuse for refusing to entertain a federal cause of action.

Rather, by distinguishing between Section 1983 claims against corrections officers and all other Section 1983 suits, New York undermined the federal policy of making relief under Section 1983 broadly available. The Court held that this was impermissible: having made the decision to create courts of general jurisdiction that regularly sit to entertain analogous suits, New York is not at liberty to shut the courthouse door to federal claims that it considers at odds with its local policy.

The question of state court enforcement of federal law is related to, but distinct from, the anti-commandeering doctrine. In Printz v. United States, the Supreme Court distinguished between federal control over state courts and commandeering of the political branches of state government. Justice Antonin Scalia’s majority opinion surveyed federal legislation from early Congresses that required state courts to take certain actions, such as recording applications for citizenship, but noted that state courts are bound by the Supremacy Clause, which expressly requires them to apply federal law. The Court thus concluded, we do not think the early statutes imposing obligations on state courts imply a power of Congress to impress the state executive into its service.

Supreme Court Review of State Court Interpretations of Federal Law

As a substantive matter, state courts interpreting federal law are bound by applicable federal court precedents and subject to review by the Supreme Court. This rule dates back to Section 25 of Judiciary Act of 1789, which authorized the U.S. Supreme Court to review certain decisions of the states’ highest courts involving the construction of the Constitution, a treaty, or federal law.

The Supreme Court considered a constitutional challenge to Section 25 in the 1816 case Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee. In that case, litigation involving title to land in Virginia was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held that a treaty between the United States and Britain controlled the dispute. On remand, the Virginia state court of appeals refused to honor the Supreme Court’s judgment, opining that the appellate power of the supreme court of the United States does not extend to this court under a sound construction of the constitution of the United States,

and that Section 25 was unconstitutional in that it extends the appellate jurisdiction of the supreme court to this court.

The case returned to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Section 25. Justice Joseph Story’s majority opinion emphasized that the Constitution vests in the Supreme Court the authority to hear all cases subject to the federal judicial power, explaining that the constitution not only contemplated, but meant to provide for cases within the scope of the judicial power of the United States, which might yet depend before state tribunals.

Similarly, in Cohens v. Virginia, individuals convicted under Virginia state criminal law for selling lottery tickets argued that their convictions violated federal law. On appeal to the Supreme Court, the state argued that while the Virginia courts were constitutionally obliged to prefer federal law over conflicting state laws, the state courts, as courts of a separate sovereign, were bound only by their own interpretation of the supreme law. The state further contended that the judicial power of the United States extended only to cases brought in the first instance in federal court. Chief Justice John Marshall’s majority opinion rejected this narrow interpretation, holding that the words of the Constitution give to the Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction in all cases arising under the constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States. The words are broad enough to comprehend all cases of this description, in whatever Court they may be decided.

Originally published by the United States Congress to the public domain.