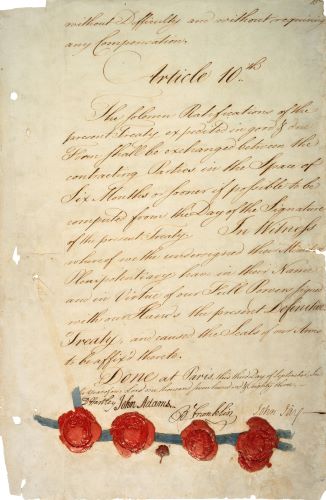

The desire to gather the papers and records of the Revolution informed a series of publishing projects.

Introduction

The literary monument to the American Revolution is vast. Shelves and now digital stores of scholarly articles, collections of documents, historical monographs and bibliographies cover all aspects of the Revolution. To these can be added great range of popular titles, guides, documentaries, films and websites. The output shows no signs of slowing. The following guide is by no means exhaustive, but seeks to define some of the contours of this output, charting very roughly the changing ways in which the Revolution has been understood or used by writers from the Revolution to recent times. Needless to say, every generation rewrites the Revolution according to its own concerns, but the questions posed by the Revolution – How is the Revolution to be defined? Did the idea of liberty, the demands of politics, or the realities of economics and society predominate? Is America in some way ‘exceptional’? – continue to be

addressed. A short bibliography, including helpful and accessible introductory and historiographical works, follows this short essay.

Early Histories

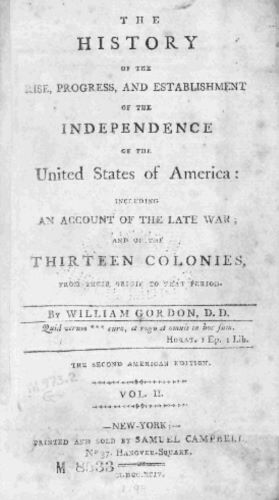

In 1788, William Gordon, a dissenting minister, published the first proper history of the Revolution, his four-volume, epistolary History of the Rise, Progress and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America.1 Gordon noted in the preface to his work that ‘History has been stiled, “The evidence of time – The light of truth – The school of virtue – The depository of events’. For Gordon, like many of his contemporaries, history was an attempt to explain the ‘principles on which states and empires have risen to power and the errors by which they have fallen into decay or have been totally dissolved’. He found the errors easily enough in the ‘sins of the Crown’, which attempted to usurp the liberties and inherited English constitutional rights of the settlers. Gordon securely placed the Revolution within a tradition of historical writing that told the story of a gradual, but inevitable, spread of liberty. David Ramsay’s History of the American Revolution (1789), pressed the point further, arguing that the colonies had developed their own form of freedom and government, creating a polity that was without historical parallel. The world, he announced, ‘had has not hitherto exhibited so fair an opportunity for promoting social happiness… we behold our species in a new situation’.2 His work, like other Revolutionary histories, contributed to this project, helping to define and construct the early American nation by educating and

informing his readers. This idea of America’s special destiny and of ‘American exceptionalism’ would become a central part of the U.S.’s national myth and theme for many subsequent historians and writers.3

Gordon and his contemporaries also began the work of gathering the materials on which to base the study of the Revolution. Ramsay noted that ‘As I write about recent events, known to thousands as well as myself, proofs are at present less necessary than they will be in the future.’4 They did not seek to distort the truth, but believed that patient collection and study of the source materials would reveal the meaning of history. The ideal historian, Gordon pointed out, ‘should have neither country, nor particular religion’ and he assured the public that ‘he has paid a sacred regard to truth… and has labored to divest himself of all undue attachment to every person.’5 His history was based on the ‘best materials, whether oral, written, or printed’, and he inspected the records of the United States Congress and the papers of Washington, Gates, Greene, Lincoln and Otho Williams, as well as the papers of the Massachusetts’ Bay Company. Gordon’s expression of concern for objectivity and the collection and consultation of contemporary materials informed many late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century accounts. Ramsay similarly made great claim to the fact that he had ‘access to all the official papers of the United States. Every letter written to Congress by General Washington, from the day he took the command of the American army till he resigned it, was carefully perused, and it’s [sic] contents noted. The same was done with the letters of other general officers, ministers of Congress, and others in public stations.’

The desire to gather the papers and records of the Revolution also informed a series of publishing projects, notably Jared Sparks’ series on the papers of public figures of the Revolution, such as Benjamin Franklin. Sparks was also well known for his biographies of the ‘Founding Fathers’, including Ethan Allen and George Washington; indeed, a fascination with individual actors in the Revolution became the dominant historical mode.6 Whether scholarly, in the works of Mercy Otis Warren, or more popular, as in the ‘book-peddling parson’, Mason Locke Weem’s hugely successful Life of George Washington (1801).7

The American Epic, George Bancroft, and Liberal Patriotism

All these works shared the general assumption that man’s tendency towards liberty and self-government drove the historical process. Furthermore, they often concluded that North America provided a remarkably suitable environment for these desires to flourish. Such ‘Whig’ writings found their apogee in George Bancroft’s massive ‘multivolume sermon’, the History of the United States (1834-1874), whose ‘great principle of action’ was the pursuit of liberty.8 The History offered a detailed, authoritative and hugely influential account of the Revolution as a search for national liberty. Bancroft, who had come of age during the patriotic fervour that followed the war of 1812 and well-read in Romantic literature, such as that of Sir Walter Scott, provided a vivid portrait of the birth of nation, from the landing at Jamestown in 1607 to the adoption of the Constitution in 1788. He charted America’s providential course from arbitrary rule to self-government, and argued that the United States was a creation of Divine Providence,

that ‘mysterious influence [which] enchains the destinies of states.’9 He offered his readers assurance that the America people had faced challenges before and would surmount future ones, so long as they held to their cherished Constitutional arrangements. Bancroft, and his readers, could find moral or political guidance for their current dilemmas in the nation’s history. As secretary to President Polk, Bancroft signed the order leading to the Mexican war, and supported Californian independence as part of the nation’s ‘Manifest Destiny’; he also came to see that the unity of the nation depended on abolition of slavery, an ‘unjust, wasteful, and unhappy system… fastened upon the rising institutions of America… by the mercantile avarice of foreign nations.’10

Bancroft’s liberal patriotism was generally shared by historians outside of the U.S., including W.E.H. Lecky and George Otto Trevelyan, and was hugely influential in his day, but it was rejected by a generation of scholars trained in the new methods of scientific history.11 Earlier historians were denounced for relying on biased or unverified printed accounts, such as the Annual Register, for their source material and

sometimes simply copying or paraphrasing its content. Bancroft was questioned on matters of fact and interpretation.12 More seriously, the assumption that a desire for liberty drove the historical process was challenged by a world-view that placed economic interests at the heart of social and political change. Bancroft’s providential historical view was also challenged by another influential history, Henry Adams’s

deeply pessimistic The History of the United States during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1889-1891). The ideals of the revolutionaries were betrayed by the failings of human nature and the interventions of other nations, all, wrote James, ‘were bourne away by the stream, struggling, gesticulating, praying, murdering, robbing; each blind to everything but a selfish interest, and all helping more or less unconsciously to reach the new level which society was obliged to seek’.13 Bancroft’s work was not free of such fears.

The Imperial School and British History

Historians also responded to Bancroft’s narrow nationalism, and from the late nineteenth-century sought to explain the Revolution in terms of the British empire as a whole, explaining with scientific, historical rationalism the relationship between Britain and the colonies. By the 1920s, historians such as Herbert Levi Osgood, George Louis Beer and Charles McLean Andrews showed that the British government was not, as Osgood wrote, ‘guilty of intentional tyranny toward the colonies’ but rather responded to provocations from the colonies and fears of French influence. Nonetheless, a desire for liberty remained the long-term cause of the Revolution, with Andrews showing how a divergence in social, economic and environmental conditions created ‘new wants, new desires, and new points of view’ in America, which led over time to a ‘new order of society’.14 These concerns with the imperial setting were investigated in ever-greater detail by a second generation of imperial historians, culminating in Lawrence Henry Gipson’s fifteen-volume The British Empire before the American Revolution.15

American historians’ concern with imperial dimension of the conflict was paralleled by a new ways of the writing of eighteenth-century British history. Lewis Namier’s work transformed understandings of the structure and working of British government, arguing that politics took place among a narrow elite, which was reflected in the make-up of the House of Commons and was best studies in biographical terms of loose faction, family, or commercial groups, rather than by party. In general, this elite ‘political nation’

accepted the Whig terms of the Revolutionary Settlement, and that politics was a matter of the struggle for office and influence, rather than ideology. Namier also reasserted the importance of the monarch to politics.16 The implications of this interpretation for the study of the Revolution, which Namier himself did not examine in any great detail, dovetailed neatly with the imperial view. George III and his politicians were engaged in local squabbles, rather than tyrannical plans; the king was also bound to support the constitutional arrangements that the colonists demands for extra-Parliamentary rights undermined.

The ‘political nation’, as studies by John Brooke and others demonstrated, was not divided by the American question until 1775. It supported the right for Parliament to tax the colonies, but the detail of policy was a result of factional squabbles, rather than a real concern with the American question. The structure of British politics did not allow for a flexible, pragmatic response to the American demands.17 More popular and radical responses to the Revolution and War have been studied, as well as its consequences for British culture and politics.18 J. C. D. Clarke has ingeniously asserted the importance of legal and religious language and symbolism for British and American society, arguing that England should be seen as a ‘confessional state’ dominated by a Anglican, monarchical and hereditary order. In the early modern Atlantic world, a cluster of ideas around the concept of a providential English destiny, as well as

dissenting, protestant theology, provided the seedbed for the constitutional ideas and collective identity of the American revolutionaries.

The Progressive Interpretation

Awareness of the inequalities in American society at the end of the nineteenth-century focused attention on earlier economic divisions amongst the colonists. A number of historians began to re-examine the conflict of interest between the property-owning elite and the poorer groups in society, such as the artisan, tenant farmer or labourer. Just as the French Revolution was thought to have been the result of class conflict, so the American Revolution could be seen as a battle for democracy by the disenfranchised.

The Progressive movement saw economics as the agent of change, making historians sceptical of the influence of ideas or ideology, preferring to see concepts such as ‘republicanism’ as an abstraction hiding deeper, ‘real’ rational and economic motives.

When Charles H. Lincoln examined Pennsylvania society and Carl L. Becker studied New York during the Revolutionary era, they discovered that responses to the Revolution could be explained by pre-existing social conditions. Becker, for example, showed how the radical poor were pitched against a commercial and property-owning elite in New York. Such economic and social causes were seen on a national level in

Arthur Meier Schlesinger’s 1918 study, The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution, which argued that the commercial classes acted in their own interests, at first opposing British restrictions, then attempting to operate as a break on the more radical, democratic demands of the popular classes. J. Franklin Jameson’s The American Revolution Considered as a Social Movement (1926) saw the Revolution as a great social revolution, in which colonial society was transformed. For Jameson, ‘The stream of revolution,’ he wrote, ‘once started, could not be confined but spread abroad upon the land.’ Finally, the Confederate Period was shown to be a moment of an important clash between the aristocratic and the democratic. What had traditionally been seen as a political conflict between federalists and antifederalists, was shown by Merrill Jensen in The Articles of Confederations (1940) and The New Nation (1950) to

have been a successful, social ‘conservative counter-revolution’ against the ‘will of the people.’ The historical consensus saw the Revolution as a socioeconomic event, the outcome of an internal contest between colonial ‘aristocrats’ and ‘democrats’ in which the constitutional conflict with Britain was of a secondary importance.

The Neo-Whig Interpretation

Indebted to social and economic theory, the Progressive view of the Revolution placed little emphasis on human agency or the role of ideas and placed the causes of the Revolution far back into the colonial past. A generation of historians who began to publish during the Cold War rejected his view, and instead projected a Revolution that was preoccupied with political questions and constitutional debate. Dubbed ‘neo-Whigs’, since they reasserted the colonist’s emphasis on liberty and constitutional rights, this influential group of historians took the time to study the great output of pamphlet literature produced before and during the Revolution. Here they discovered a greater coherence and sophistication amongst colonial thought than assumed by the Progressives or was expressed by the first generations of historians.19 As Edmund S. Morgan and Helen M. Morgan’s argued in The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (1953), the Revolution could be explained by the power of the idea of constitutional liberties. By re-examining one of the most studied pre-Revolutionary events, they demonstrated the ideological coherence of the colonists, and argued that ideas were not a means of disguising economic motives. In short, there was no class-based Revolution.

The dominance of political ideology in the Revolution was further reinforced by the work of Bernard Bailyn, who in The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967) mined the rich seam of pre-Revolutionary pamphlet material to argue for an ‘ideological-constitutional struggle’, indebted to the political opposition in Walpolean Britain who emphasised the dangers of conspiracy and corruption.20 Alert to such potential tyranny, the colonists viewed British behaviour through this lens of political

language. In 1969, Gordon S. Wood argued in The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 for the vital importance of a serious political debate over the need to create a virtuous citizenry versus the creation of ‘institutional contrivance’ to defeat the growth of government corruption.21 The American Revolution, as Daniel J. Boorstin argued in The Genius of American Politics, was again seen as ‘a victory of constitutionalism’; a conservative Revolution that sought to assert existing constitutional rights, rather than a social conflict.22

Specialisation and the Return of the Narrative

The growth of the professional historical profession during the 1950s and 1960s, the development of research libraries and archives, and the steady publication of edited collections of primary sources underpinned a continual growth in research on the American Revolution. Although ‘neo-Progressive’ historians, such as Staughton Lynd, continued to emphasise the socioeconomic roots of the Revolution, the neo-Whig interpretation remained the dominant overall interpretation of its origins and nature.23

New historical methods, influenced by the social sciences and cultural theory, the political concerns of the New Left, and a growing awareness of the need for histories of race and gender immensely broadened historians’ questions, approaches and subject matter. Along with numerous local studies, historians began to reconstruct the huge varieties of America’s communities and subcultures, recreating lost mental, psychological or physical worlds and putting into better focus issues of slavery and religion. These groups have also included Loyalists, who were most often neglected in previous accounts. Important studies include those of Wallace Brown, The Good Americans (1969), Robert M. Calhoon, The Loyalists in Revolutionary America (1973), William H. Nelson, The American Tory (1961), William A. Benton, Whig-Loyalism (1969) and Esmond Wright (ed), A Tug of Loyalties (1975). An interest in the wider world continues, not least because of the reconception of early modern colonies and nations as part of a complex ‘Atlantic World’.24

Finally, after several decades of increasing fragmentation and specialist analysis, historians have returned to narrative. A scholarly interest in narrative coincided with the growth in popular histories, biographies and syntheses. Blockbuster biographies many of the Founding Fathers have stormed the bestseller charts, and debates, particularly the slave-owning Fathers, have been drawn into the ongoing culture wars.25 The work begun by Gordon and others shows no sign of slowing.

Endnotes

- Alexander Gordon, rev. Troy O. Bickham, ‘Gordon, William (1727/8–1807)’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004), http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11088 (accessed March 9, 2007). It was published in London, rather than the United States as he suspect that an impartial account would not be welcome in the new republic. Despite his fears, Gordon found a number of American subscribers, including George Washington, and it was published in New York in the following year. Gordon’s work was not reprinted after the third, U.S. edition, in 1801 until 1969.

- David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution (London, 1792 edition), vol. 1 p. 356.

- Arthur H. Shaffer, ‘Ramsay, David (1749–1815)’, ODNB [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/68646, accessed 12 March 2007]; Arthur H. Shaffer, To Be an American: David Ramsay and the Making of the American Consciousness (Columbia, 1991), but see also Karen O’Brien, ‘David Ramsay and the Delayed Americanization of American History’, Early American Literature 29:1 (1994), pp. 1-18, who argues that Ramsay is best seen in the context of eighteenth-century historiography, rather than a harbinger of nineteenth-century Romantic history. On the U.S.’ national ‘myth’, see Michael Kammen, A Season of Youth: the American revolution and the historical imagination (New York, 1978).

- Ramsay, History, preface.

- William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independent United States of America: including an account of the late war, vol. 1 (London, 1788).

- Jared Sparks, The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution. Being the letters of Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, John Adams… and others, 12 vols. (Boston [Mass.], 1829, 30); The Writings of George Washington, being his Correspondence, Addresses, Messages and other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original MSS.; with a life of the author, notes and illustrations, 12 vols. (Boston, [Mass.], 1837-33-36).

- Mercy Otis Warren. History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution: interspersed with biographical, political, and moral observations (Indianapolis, 1988, 1805).

- Sir Herbert Butterfield, The Whig Interpretation of History (London, 1931); Bernard Bailyn, ‘A Whig Interpretation’, Yale Review, 50 (1961), pp. 438-41. Bancroft’s first volume appeared in 1834 and he published the final narrative (vol. 10) in 1874. Bancroft continued to revise the text and a six-volume Centenary Edition appeared in 1876; two volumes relating to constitutional ratification were published in 1882. The final Author’s Last Revision was published between 1882 and 1884. Bancroft died in 1889. A useful abridgement is The History of the United States of America from the Discovery of the Continent, ed. Russel B. Nye (Chicago, 1966). See also Russel B. Nye, George Bancroft. Brahmin Rebel (New York, 1944).

- Quoted in Arthur H. Shaffer, The Politics of History: writing the history of the American Revolution 1783-1815 (Chicago, 1975), pp. 178-79.

- Quoted and discussed in Hoffer, Liberty or Order, p. 268.

- W. E. H. Lecky, A History of England in the Eighteenth Century, 8 vols. (London and New York, 1878-1890); George Otto Trevelyan, The American Revolution, 4 vols. (London and New York, 1899-1913). See Jack P. Greene, Interpreting Early America. Historiographical essays (Charlottesville & London, 1996), pp. 367-9.

- Gordon noted in his preface to his History that ‘the Register and other publications have been of service to the compiler if the present work, who has frequently copied from them, without varying the language,

except for method and conciseness.’ Orin G. Libby, ‘A Critical Examination of William Gordon’s History of the American Revolution’, Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1 (1899), pp. 367-88; ‘Some Pseudo Histories of the American Revolution’, Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, 13:1 (1900), pp. 419-25; ‘Ramsay as a Plagiarist’, American Historical Review, 7 (1902), pp. 697-703; Watt Stewart, ‘George Bancroft Historian of the American Republic’, Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 19: 1 (1932), pp. 77-86. - Henry Adams, The History of the United States during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1889-1891), vol. 4, p. 302.

- Herbert L. Osgood, ‘The American Revolution’, Political Science Quarterly 13 (1898), pp. 41-59; George Louis Beer, British Colonial Policy, 1754-1765 (New York, 1907); Charles McLean Andrews, The colonial background of the American Revolution (New Haven, 1924). See also Greene, Interpreting Early America, pp. 369-72.

- Lawrence Henry Gipson, The British Empire before the American Revolution (Caldwell, Ohio, 1936).

- Lewis Namier, The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III, 2 vols. (London, 1929), and England in the Age of the American Revolution (London, 1930).

- John Brooke, The Chatham Administration, 1766-1768 (London, 1956); Charles Ritcheson, British Politics and the American Revolution; Richard Pares, King George III and the Politicians.

- Ian R. Christie, Wilkes, Wyvill, and Reform: the Parliamentary Reform Movement in British Politics, 1760-1778, (London and New York, 1962); Paul David Nelson, ‘British Conduct of the American Revolutionary War: a review of interpretations’, The Journal of American History, 65:3 (1978), pp. 623-653; Stephen Conway, The British Isles and the American War of Independence (Oxford, 2000).

- The term ‘neo-Whig’ was coined in Jack P. Greene, ‘The Flight from Determinism: a review of recent literature on the coming of the American Revolution’, South Atlantic Quarterly 61 (1962), pp. 235-59; reprinted in Greene, Interpreting Early America, chapter 17.

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1967).

- Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1969).

- Daniel J. Boorstin, The Genius of American Politics (Chicago, 1953).

- Staughton Lynd, Class Conflict, Slavery and the United States Constitution (1968).

- On British culture in America, see Eliga H. Gould, The Persistence of Empire: British political culture in the age of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, N.C. and London, 2000). On the Atlantic World, Elliott, John Huxtable. Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America, 1492-1830 (New Haven, Conn. and London, 2006). For both, see Nicholas P. Canny and A. R. Pagden, Colonial Identity in the Atlantic World. 1500-1800 (Princeton and Guildford, 1987).

- Notable examples include: David G McCullough, John Adams (New York, 2001), 1776 (New York, 2005). Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (London, 2004); Simon Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution (London, 2005).

Bibliography

General and Introductory Works

- Conway, Stephen, The War of American Independence (London, 1995).

- Derry, John W., English politics and the American Revolution (London, 1976).

- Dickinson, H. T., Britain and the American Revolution (London and New York, 1998).

- Holton, Woody, Forced Founders: Indians, debtors, slaves, and the making of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, 1999).

- Jones, Maldwyn A. The Limits of Liberty. American history 1607-1992, 2nd edition (Oxford, 1995), chs. 3, 4.

- Morgan, Edmud S., The Birth of the Republic, 1773-1789, 3rd edition (Chicago and London, 1992).

- Middlekauff, Robert, The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution 1763-1789 (Oxford, 2005).

- Wright, Esmond, Fabric of Freedom, revised edition (London, 1980).

- Wood, Gordon, The Creation of the American Republic 1776-1787, 1993 printing (New York & London, 1993).

Historiographical Works

- Greene, Jack P., Interpreting Early America. Historiographical essays (Charlottesville and London, 1996).

- Hoffer, Peter Charles, Liberty or Order: two views of American history from the revolutionary crisis to the early works of George Bancroft and Wendell Phillips (New York and London, 1988).

- Kammen, Michael, A Season of Youth: the American revolution and the historical imagination (New York, 1978).

- Nelson, Paul David, ‘British Conduct of the American Revolutionary War: a review of interpretations’, The Journal of American History, 65:3 (1978), pp. 623-653.

- Newman, Simon P., ed., Europe’s American Revolution (Basingstoke, 2006).

- Shaffer, Arthur H., The Politics of History: writing the history of the American Revolution 1783-1815 (Chicago, 1975).

Atlases, Bibliographies, and Historical Dictionaries

- Adams, Thomas R., The American Controversy: a bibliographical study of the British pamphlets about the American disputes, 1764-1783 (Providence and New York, 1980) [HLR 973.27 Open Access; see also the related microforms at MFR/1700 5409 DSC].

- Gephart, Ronald M., Revolutionary America, 1763-1789: a bibliography (2 vols. Washington, D.C., 1984) [HLR 973.3 Open Access].

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole, A Companion to the American Revolution (Malden, Ma. and Oxford, 2000).

- Jones, Maldwyn A. The Limits of Liberty. American history 1607-1992, 2nd edition (Oxford, 1995), includes a useful bibliographic guide.

- Mays, Terry M. Historical Dictionary of the American Revolution (Lanham and London, 1999) [HLR 973.303 Open Access].

- McEvedy, Colin, The Penguin Atlas of North American History (Harmondsworth, 1988).

- Smith, Dwight L., ed. Era of the American Revolution: a bibliography (Santa Barbara, Calif., 1975).

Originally published by the British Library under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.