Dia speiro (“to sow over” or “to scatter about”) indicates a transplanting of a culture from one area to another.

By Dr. Rebecca Denova

Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies

University of Pittsburgh

Introduction

A diaspora is a large group of people with a similar heritage or homeland who have since moved from their original homelands to another country. In terms of ethnicity, they share a common language, worldviews, myths, religious concepts and rituals, social customs, and food. The Greek term dia speiro (“to sow over” or “to scatter about”) indicates a transplanting of a culture from one area to another.

Bronze Age Collapse

Then as now, the migration of peoples occurred for many reasons. Hunter-gatherers relocated following herds of animals or in search of new grazing lands. With the introduction of agriculture, movement expanded when small plots no longer produced enough surplus for trade. The establishment of urban centers provided movement from the countryside, especially with the evolution of technology and crafts that became part of the larger economy.

In the Western tradition, we first began seeing a reference to the concept of diaspora in the region of the Eastern Mediterranean Basin. At the end of the Bronze Age, the region was collectively invaded by a group known as the Sea Peoples who established colonies and cities. Great sea traders and merchants, they are the Philistines of the Bible. Their origin remains unknown, but the prevailing theories indicate an origin in and around the Mediterranean. This is the beginning of the Iron Age, with the introduction of new weapons and tools.

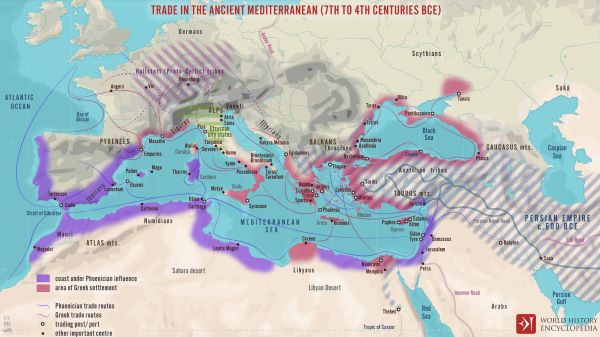

The Phoenicians came to prominence at this time, collectively categorized as older Canaanite tribes of the Levant region. Also great seafarers and traders, they established colonies from Cyprus to the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. The Greek term for these people (phoenix) became “Punic” in Latin (thus the Punic Wars of Rome against Carthage). The Phoenicians are now credited with the introduction of their alphabet for Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, and Cyrillic systems.

Greek Expansion

In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, Greece began establishing colonies throughout the Mediterranean Basin. Factors such as periodic famines, plagues, wars between the city-states, and the need for larger commercial outlets contributed to these migrations. They settled around the Black Sea, Anatolia (Turkey), Southern France, Southern Italy, and Sicily. The area of Greek settlement in Italy was called Magna Graecia (“Greater Greece”). This Hellenic culture was fused with the indigenous tribes of Italy and greatly influenced the emerging culture of Rome. Rome conquered the Greek city of Neapolis in 327 BCE, followed by other conquests and eventually conquered Sicily.

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) was proud of his Greek heritage; he had been tutored by Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Everywhere he conquered, he introduced Greek philosophy, language, governance, religion, and education. After the conquests, Alexander settled his veterans in colonies throughout the Middle East, where they mixed with the local cultures. This resulted in what scholars term syncretism.

As a conqueror, Alexander could have demolished all local cult centers. Instead, he layered older traditions with his own. For example, when entering a temple, he simply added a lightning bolt and hyphenated the name of Zeus to the older god. The locals were happy to keep their older gods but could now add Zeus. Zeus must have been a great god because he was the god of Alexander.

Syncretism can result in a broader, expanded worldview (old and new) or sometimes can form the basis of a new culture or a new religion. Syncretism became associated with understanding diaspora communities, which maintained their own traditions while simultaneously adopting elements of the new settlement as well as influencing the local culture.

Ancient Judaism

Like all ancient cultures, the Jews experienced migration patterns. The first traditional migration took place with the call of Abraham to leave his homeland (at the head of the Persian Gulf) with his family and settled in Canaan. According to the book of Exodus, a second major migration took place when there was famine in Israel, and the Jews migrated to Egypt and established a large community.

But the descriptive Greek term ‘diaspora’ came into use after the Assyrian destruction of the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE and the Babylonian destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 587 BCE. Both conquerors had a program of population exchanges. Of the twelve tribes of Israel, the ten Northern tribes were taken to Assyria and became ‘lost’ to history. The Jews of Jerusalem were taken to the capital city of Babylon; the period became known as the Babylonian Exile.

Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) conquered the Babylonians. He granted the Jews funds to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the city and rebuild the Temple. However, life in the Achaemenid Empire led to the prosperity of the Jewish community, and many decided to stay. This is when the term diaspora (often translated into the English “dispersion”) was utilized to describe communities living outside of the land. Jews established synagogue communities throughout the Roman Empire and beyond.

Diaspora Studies

The study of diaspora communities only became popular after the introduction of the disciplines of the social sciences into academia in the 1900s. Studies analyze cultural adaptations in both conceptual thinking, socialization, and behavior. These factors help to categorize the differences between migration and what can be understood as a diaspora community. For example, in Europe, during Late Antiquity, major migrations of tribes of Goths, Visigoths, Vandals, Huns, and the later Viking raids, did not result in the formation of unique ethnic and cultural communities; they were absorbed into the cultural traditions of Europe. Outside of the Western tradition, migration communities from China, Korea, Japan, and India to the South Pacific and beyond are analyzed. African migrations (including the forced migrations of slavery to the New World) are also the subject of study.

Comparative analyses of common factors that both motivate migration as well as adaptability are of renewed interest in the postcolonial world. Many diaspora communities share a common history of persecution and/or expulsion from their original homelands. This has resulted in the politicization of diaspora ideology. In some countries, diaspora communities present themselves as oppositional nation-states against the continuing tyranny of their homelands (governments-in-exile). After World War II (1939-1945), dozens of countries in the French and British Empires sought independence. Embroiled now in civil wars, many groups migrated to the original host countries, rejecting the imposition of some of the new systems. This period saw a globalization of diaspora communities throughout the world.

Other scholars focus on the problem of unequal resources, unemployment, and lack of educational opportunities for the motivating elements of migrant communities. At times, the host country can stimulate migration for economic reasons. For example, the United States began importing Chinese workers in great numbers to work on the construction of railroads in the western states in the 19th century.

The Politics of Diaspora

A common feature of diaspora communities is that they maintain a relationship and loyalty to their home country and traditional customs. However, during a geopolitical crisis or war, this loyalty can be construed as a threat. Although the FBI investigated German and Italian Americans, the Japanese communities on the West Coast were relocated to internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor, from 1942 to 1945. This included American citizens and their children. Now viewed as a black stain in American history and a violation of constitutional rights, a similar reaction occurred against Muslim Americans after the terrorist attacks on 9/11.

The Armenian people were absorbed into the Ottoman Empire. Fearing an internal rebellion, the Ottoman government ordered the mass slaughter and deportation of Armenians during World War I (1914-1918). From then until now, Armenian communities have protested the current Turkish government’s refusal to label this a genocide in the history of this period. As of 2021, 31 countries have recognized the event as genocide.

Science

The popular interest in diaspora communities utilizes the sciences of DNA studies and genome tracking to analyze both the origin of a people as well as their integration into host communities. This is particularly important in archaeological excavations of tombs and cemeteries, where DNA analysis of the skeletons can provide ancestral lineages of mixed populations to determine the degree of integration. Genome studies have been conducted in the communities along the ancient Silk Road in Asia as an effort to trace the lost tribes of Israel.

An estimated 10% of the world’s population currently live in diaspora communities. We are gradually learning to appreciate the positive benefits of these communities in the sharing of knowledge, technology, and the continuing diversity of cultural and religious views and customs.

Bibliography

- Cohen, Robin. Global Diasporas. Routledge, 2008.

- Stierstorfer, Klaus & Wilson, Janet. The Routledge Diaspora Studies Reader. Routledge, 2017.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 02.24.2022, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.