Hierarchical society flourished in ancient Egypt largely because of the central cultural principle of ma’at.

By Dr. Amy Calvert

Egyptologist and Archaeologist

A Hierarchy

Ancient Egyptian society was a strictly divided hierarchy. The king, chosen by the gods to rule, was at the top with layers underneath—including officials like the vizier, scribes, overseers, and regional governors (called “nomarchs”), priests, the military, and the general population of artists, tradespeople, craftspeople, agricultural workers, laborers, and enslaved people.

This hierarchical society flourished for much of ancient Egypt’s very long history largely because of the central cultural principle of ma’at—the cosmic force of order and balance that Egyptians believed governed their world. The economy was centrally organized, with a fixed wage and state distribution system. Through this process, the properly functioning state (proof of the king being in accord with ma’at) provided for the populace. The king officially owned all the land and the state received goods and services through taxation. Taxes were levied, collected, and recorded by the offices of the vizier and placed in centralized storehouses. These goods were then redistributed back to the people.

Pharaoh—Top of the Food Chain

Ruler’s Role

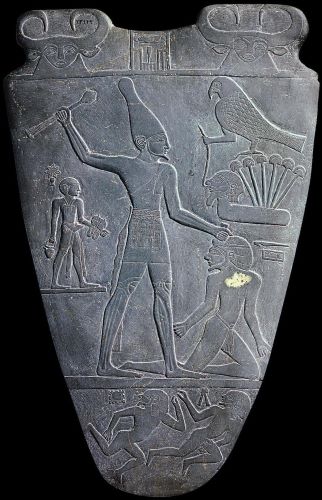

Many aspects of royal ideology and iconography were visible from the earliest monuments and continued to be used for thousands of years. The Narmer Palette for example, includes the iconic smiting pose, elements of regalia like crowns, weapons, and the ceremonial beard, and a blending of divine and terrestrial elements in the same scene in support of the king’s efforts.

The ruler’s role as the champion of ma’at was paramount, as was the expectation that a ruler would protect Egypt from its enemies and administer the vast resources of the Two Lands to the benefit of the people. As time passed, the ruler had additional expectations, including being a good shepherd and protector and, in the militaristic period of the New Kingdom, to display great skill in battle and physical prowess.

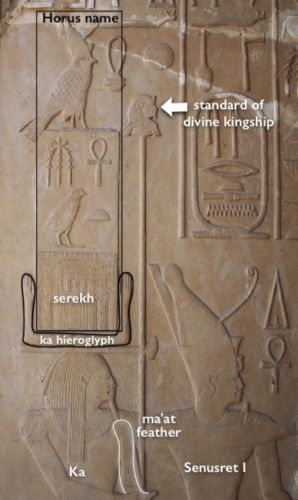

Kings in ancient Egypt were living humans, but they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler, and it was this divine aspect of the office that gave authority to the individual person who was the king. The living ruler was viewed as the embodiment of the god Horus, the powerful, falcon-headed god who was believed to have bestowed the throne to the first human king, Menes. Once they died, the ruler became connected with Osiris, the eternal Lord of the Underworld, and their successor rose as the new Horus.

King Names

Over time, the royal title developed so that each individual king had five names that emphasized different aspects of kingship and highlighted the king’s relationships with the gods.

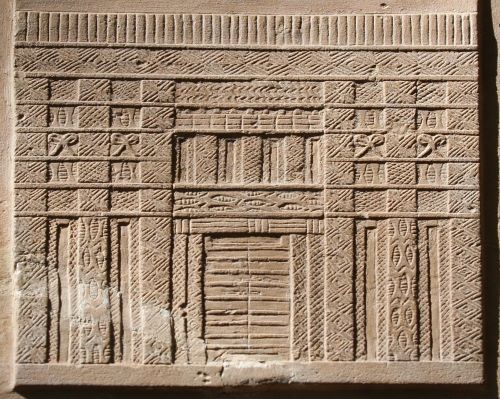

Horus-name: The earliest of the five names to appear was the Horus-name (also known as the ka-name). This name identified the king as the earthly embodiment of Horus, the patron god of kingship, and was enclosed in a serekh (a paneled rectangular form that likely represents a stylized palace gateway) topped with the Horus falcon.

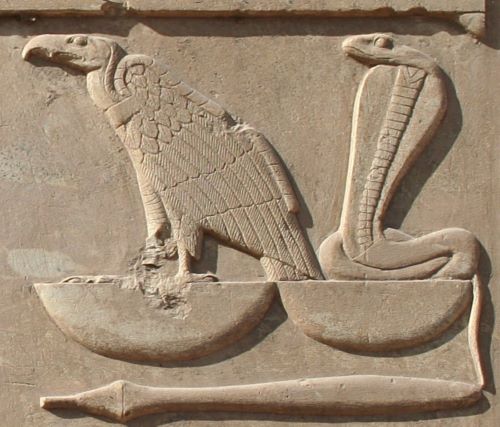

The Two Ladies-name (nebty): This name demonstrated that the Two Lands were unified under the king’s rule. This name was topped by the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet, usually represented in the title as a vulture and a cobra wearing the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, the White and Red crown, respectively.

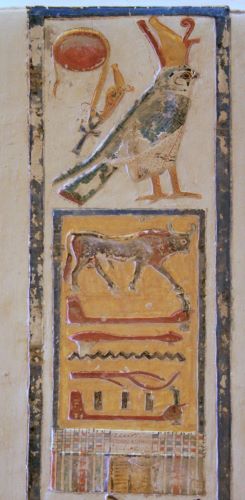

Golden Horus-name: The title of the Golden Horus-name was written as a falcon seated atop the hieroglyph for gold; the meaning of this name is unclear but likely indicates a wish for the king to be an “eternal Horus.”

nesu-bjt-name: Often referred to as the prenomen, the nesu-bjt-name is titled by hieroglyphs of a sedge and bee. Often translated as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” it seems instead to be closer in meaning to a merging of the eternal aspect of divine kingship (nesu) with the ephemeral human ruler holding power at that moment in time (bit).

The birth name or nomen: This was the only one of the five that was given to a king at their birth; the rest being given when they took the crown. The nomen is the Son of Ra-name, titled by a goose and sun disc —the hieroglyphs that spell out “son of Ra.”

Both the nomen and prenomen were enclosed in the elongated cartouche (an oval shape). This device, which may signify the infinite expanse of the king’s realm, clearly distinguished royal names from surrounding text.

Old Kingdom: First Dynasty through the First Intermediate Period

From the First Dynasty onwards, kings were known by the Horus-name. They served as political, religious, and military leaders. The ruler was expected to be the powerful champion of ma’at and capable of wielding that divine strength to protect Egypt from her foes.

The earliest sculptures of a specific ruler anywhere in the world may be two images of the Second Dynasty king Khasekhemwy wearing the White Crown and crushing chaotic enemies under his feet (one is pictured above) as an agent of ma’at. By the Fourth Dynasty, the king was viewed as the “Son of Ra,” acting as a deputy of the sun god on earth.

Kings of the Old Kingdom were viewed almost as divine; statuary of this time shows them with perfected bodies and serene faces (like Menkaura and his queen) that seemed focused on the world beyond. Toward the end of the Sixth Dynasty, several factors (including low Nile inundations that may suggest famine and apparent disorganization), led to the loss of centralized control and the end of the Old Kingdom. Simultaneously, the prominence of local governors (nomarchs) began to increase in their individual regions and rise in importance. They became increasingly independent from the king and central administration, leading to a politically fractured period we call the First Intermediate Period.

Middle Kingdom through Second Intermediate Period

After the disunity of the First Intermediate Period, we see the democratization of previously royal prerogatives (such as the assumption of royal titles, regalia, and mortuary practices by local nomarchs), and the role of the pharaoh shifted. Kings of the Middle Kingdom focused more attention on being responsible protectors of Egypt, rather than on their divinity. Statues of the pharaohs from this time convey the heaviness of the crown and the role of kingship, the weight of their responsibilities evident on the face. The ears of these figures are also distinctly oversized—the better, it is believed, to hear the pleas of their people.

During the Second Intermediate Period, peoples from western Asia took control of the Nile delta region. During this disjointed period, there was an Egyptian pharaoh ruling the south from Thebes and a Hyksos king ruling the north from a city called Avaris. Military conflicts between the two groups extended for generations and were fierce; one of the royal Egyptian mummies from this period shows severe injuries that indicate a violent death on the battlefield. Eventually, the pharaoh Ahmose was able to drive the occupiers out of the delta, re-unify the country under his rule, and establish the New Kingdom.

New Kingdom

After successfully regaining their country, New Kingdom rulers placed extra emphasis on military capabilities and were expected to be skilled in battle as the supreme commander of the armies. Perhaps in response to being invaded and occupied, the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty led numerous military campaigns and expanded the borders of Egypt north all the way to the Euphrates river, and south deep into Nubia. Even after the borders were stabilized, this role of the king as Egypt’s protector was paramount, as evidenced by the huge numbers of triumphant battle scenes that appear on temple walls.

Female Rulers

Female rulers, although rare, controlled the country at several points in Egypt’s history. One of the most famous of these was the powerful Hatshepsut, who reigned for around 20 years during the New Kingdom. A prolific builder, Hatshepsut’s magnificent terraced mortuary temple cut into the cliffs in west Thebes remains one of the most stunning structures from the ancient world.

Many of Hatshepsut’s images show her as a masculine ruler, with her feminine characteristics deemphasized and wearing all the same royal regalia as male kings. Texts on these images, however, clearly identify her properly as female. As always before the gods, it was her capabilities as a good king that was of the greatest import; her gender was not an issue.

Rulers from Abroad

Even rulers of non-Egyptian origin, including the much later Roman emperors who appear in temple relief carvings, presented themselves with the traditional iconography and regalia that clearly identified them as an Egyptian pharaoh. This practice linked them with the long line of kings that came before them and helped legitimize their rule to the illiterate populace. Rulers from Kerma, whose own culture displayed a fascinating blend of Nubian and Egyptian imagery, emphasized Egyptian deities in their monuments. These Kushite kings ruled Egypt for around 75 years. They were especially devoted to the god Amun, who had a well-established and important cult in their homeland.

King Lists

Kings recorded the names of their predecessors in vast “king-lists” on the walls of their temples and depicted themselves making offerings to the rulers who came before them—one of the best known examples is in the temple of Seti I at Abydos. These lists were often condensed, with some rulers (such as the contentious and disruptive Akhenaten and his successor, Tutankhamun) and even entire dynasties omitted from the record; they are not truly history, rather they are a form of ancestor worship, a celebration of the consistency of kingship of which the current ruler was a part.

Ancient Egyptian society has been portrayed as a pyramid, with the king at the very top and the population layered beneath them. Egypt was a theocratic monarchy, where the king ruled by the command of the gods and served as intermediary between the people and the divine. He was maintainer of ma’at, chief officiant in all ritual actions before the gods, military commander and protector of Egypt, living Horus, and provider for the people. If he fulfilled all his required roles to the satisfaction of the gods, then the land flourished and the people prospered. In general, the society was divided into those who administered (the officials) and those who were administered (the masses of the population). Given that there was no “church and state” separation, the temples were also part of the administration, lending divine oversight to state activities. All large-scale ventures, whether quarrying expeditions, building projects, or the maintenance of workshops of artisans, were controlled by the state.

Ancient Egyptian society was a theocratic monarchy with a strict hierarchical structure. The most important individual in the society, the king (pharaoh), was discussed in a separate essay. Below the king were administrative officials, such as the vizier, overseers, scores of scribes, and regional governors (called “nomarchs”) who handled local resource management. There were also priests dedicated to the divine and royal cults, ranks of the military, and the general population of artists, tradespeople, craftspeople, agricultural workers, laborers, and slaves.

The Egyptians believed their world was governed by ma’at, a divine force of cosmic balance, which is what provided stability. The centrally-organized storehouse economy and state-run distribution system supplied the people with a fixed wage based on their labor type and skill level. In general, there was little social mobility or free choice of career; instead, sons followed their fathers in their professions.

Administration: Viziers, Officials, and Overseers

Egyptian bureaucracy was hierarchical, with the pharaoh at the top and layers of administrators beneath them that governed on the king’s behalf. This group of elites were among the very small portion of the population that was literate. The top official below the king was known in Egyptian as tjaty; this individual is now referred to as the vizier (Arabic for “high official”) and was much like a modern prime minister. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms there was one vizier for the whole country, but during the New Kingdom this position was split into a vizier of Upper Egypt and another for Lower Egypt (from the beginning of its history, Egypt was viewed as being two lands: Upper Egypt in the south, and Lower Egypt in the north), while a third, the Viceroy of Kush, oversaw the valuable lands of Nubia south of the First Cataract.

These high-ranking figures functioned as the king’s representatives and directed the administration of the country. Below them were the local officials and provincial governors who performed a range of responsibilities—most importantly the collection of taxes, oversight of local granaries and storehouses, and drafting of labor for state projects. They were accountable to the vizier for any failures. Civil justice was meted out by councils of local officials and high-ranking priests. The vizier served as the chair of the “Great Council,” which oversaw cases that affected the state, such as property disputes that could impact taxation and serious crimes like murder. Local councils oversaw social claims such as theft, adultery, and wife-beating—both men and women had the right to seek redress in court.

Scribes and Priests: Holders of Secret Knowledge

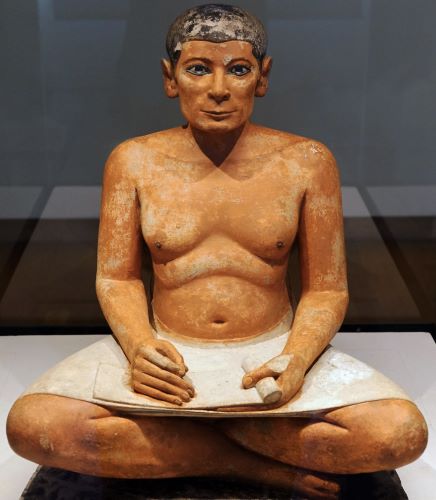

The scribal class was part of the administration and they were high-ranking professionals. These individuals could understand and write hieroglyphs, which the ancient Egyptians called medu netjer or “words of the gods.” The word for scribe was written hieroglyphically as a scribal palette with ink recesses and an attached stylus.

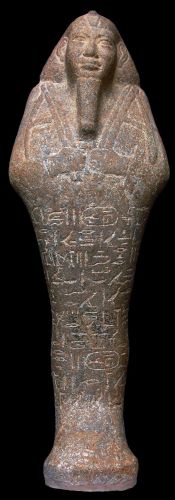

Scribes served an essential function in society and were often portrayed as serene, confident, and self-assured in their elevated position. They were trained in special schools associated with the court and certain temples, with students focused on copying existing texts. Training seems to have been based on memorizing entire sections of text rather than individual signs. The Egyptian language developed over time and was not only written in the fully pictorial hieroglyphic script, but also in other forms of the language. Although the hieroglyphic script is entirely made up of images, it was not pictographic writing. Instead, these signs stood for sounds or groups of sounds that were clustered together to form words. Scrolls of papyrus were the usual surface for formal texts, although many informal texts were jotted down on sherds of pottery or flakes of stone known as ostraca. Ink was applied using a reed stylus; black for the primary writing and red for headings and corrections.

Scribal training was required to become an official, a physician, or a priest. As most diseases were thought to have come as a punishment from the gods or divine lesson, there was little distinction between priests and physicians and in some sects, like that of the goddess Serket, all the priests were also doctors. Priests needed to be able to read and write in order to perform their duties; many of the rituals had long incantations that had to be read. It is interesting to note that no separate priestly class existed until the New Kingdom. Prior to this time, priestly duties were performed by civil officials who served for a period of months and then returned to their regular, secular tasks.

New Kingdom priests were trained as scribes and then submitted to a series of ritual purifications and annointings along with vows of purity and obedience. There were strict requirements for purity, including shaved heads and regular washings, as well as proscriptions from certain foods and activities while in the service of the gods.

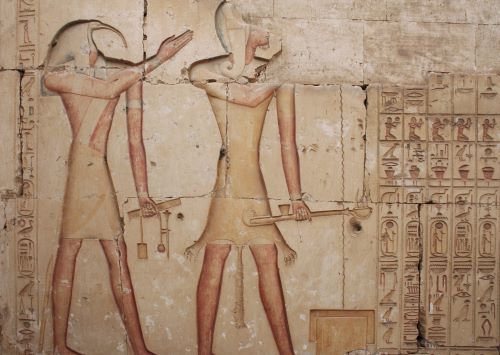

Several different types of priests are known from early times. For instance, there were lector priests, who wore a diagonal sash across their chest and recited the formulas that accompanied cult rituals, while sem priests wore leopard skins and were associated with funerary rites and the essential Opening of the Mouth ritual.

At the numerous divine and royal temples throughout the country, the administrations included overseers and inspectors of the priests who were responsible for the organization and management of the daily operations of each temple. At the top of the hierarchy was the high priest who was referred to as the hem-netjer-tepy or “first servant of god.” This position was frequently appointed by the king but over time it became more hereditary. Priestesses are known from the Old Kingdom onwards, with many elite females holding the title of hemet-netjer, “(female) servant of god.” Usually, women served female deities although some seem to have served as priestesses of Thoth and Ptah.

Military: Shield of Egypt

We know little about the military until the New Kingdom and there was apparently no standing army until at least the Middle Kingdom. Prior to this, if troops were needed they were conscripted, armed—with hide-covered shields, clubs, battle-axes, daggers, simple bows and arrows, slings, and lances—and placed under the command of a local official who was their superior in civil life. After the Old Kingdom, mercenaries and professional soldiers appeared and a permanent fighting force developed. In addition to forts in the eastern desert and along trade routes, Middle Kingdom rulers established a series of riverine forts in Nubia that were well-manned and used to establish control of the valuable resources in the region, especially gold.

Models from the Middle Kingdom tomb of Mesehti show 2 units of armed soldiers (40 Egyptian foot soldiers and 40 Nubian archers) preserving their costumes and weapons. During the New Kingdom, the military machine massively expanded. Major military campaigns were carried out throughout this period and supported a mass of professional troops. The New Kingdom was founded on generations of battle, with the need to drive the Hyksos out of the Nile delta. The Egyptian military embraced the weapons that had been introduced by the Hyksos, including the scimitar, horse-drawn chariot, and composite bow, and made them their own. New Kingdom kings greatly expanded the borders of their influence. A rare gateway to social mobility, prowess in battle and military capabilities could elevate the status of even the lowest-born soldier to that of a distinguished veteran.

Artisans and Craftspeople: Creators of Beauty and Function

Below the scribal layer were semi- or non-literate skilled artisans and craftspeople who produced the goods required by the elite. Although for most of Egypt’s history, we know little about individual craftspeople, surviving examples show that some were honored with statues and private tombs—one early, 3rd Dynasty example being a ship-builder and smith named Akhwa who was identified as a “Royal Acquaintance.”

The special village of Deir el-Medina on the west bank at Thebes provides a unique view into the daily lives of this class during the New Kingdom. For many generations, the artisans who dug out and decorated the royal tombs of the Valley of the Kings lived with their families in this isolated village on the edge of the desert. Due to their professions, a significant portion of the population of this village could read and write and excavations have revealed tens of thousands of ostraca (texts were jotted down on sherds of pottery or flakes of stone).

Basically the “post-its” of the ancient world, there were used for all sorts of lists, letters, simple notes, and creative drawings and provide an intimate look at their day-to-day interactions. One of the most fascinating events recorded was a worker’s strike that occurred at Deir el Medina in around 1150 B.C.E. A state shortfall had resulted in a delay of the worker’s wages and the royal artisans stopped working until the matter was addressed. The vizier himself came to the village to assure them assistance was coming, but when that fell through they struck again and even took control of the royal mortuary temples. Eventually, their demands were met and they returned to work, having successfully won the first recorded labor strike in history.

Agricultural Workers and Laborers: Producers of the Bounty

The largest portion of Egypt’s population were the illiterate masses who worked the land as independent farmers or agricultural laborers. This strata generated the crops, produced the foodstuffs, and raised the animals that supplied the populace and elite classes with the bounty of the land. This is also the group that provided much of the paid labor force for state building projects, such as the pyramids. During the annual flooding of the Nile, when it became impossible to work in the fields, these laborers were conscripted to go work on the king’s state-funded projects instead. Much less is directly recorded by this class, as they did not have the resources to commission monuments nor the knowledge to write texts. We do have some information about their lives and work through the viewpoint of the elite, although these representations depict them in terms of their service to and supporting the nobles rather than in their own right.

Images of these classes in private tombs, whether in relief or in statuary, tend to show great freedom in the way they are rendered in pose, action, and realism. They are depicted in a wide range of activities—such as gathering fish from the Nile, herding cattle, weaving cloth, making bricks, hewing wood, grinding grain, baking bread, and brewing beer—which were intended to provide benefit for the deceased in the afterlife. It was their actions performed on behalf of the deceased, rather than the figure itself, that was considered important. Regardless of the level to which they are recorded, it is clear that this group—responsible for maintaining agricultural production—was the backbone of Egyptian society.

Slaves: Through Capture and Debt

Given that the Egyptian population was not “free” in the modern sense (in general, they could not move freely around the country or change their professions) the idea of “servitude” was viewed quite differently. Tied to the land, the vast majority of the population were considered “possessions”of the king, temple estates, or high-ranking officials, somewhat like serfs in the feudal society of medieval Europe. These peasants worked the land and paid tribute to their masters as a form of social insurance; in times of drought the landowner would open their storehouses and granaries to provide for their people. Through this administrative structure, subjects were provided with a sense of security that fostered stability and growth.

In Egypt, as elsewhere, the oldest and primary cause of slavery was capture in battle. Conquered soldiers and their communities were taken as a royal resource. Those captives who weren’t retained by the royal administration would be distributed to various towns, quarries, and temples to augment their labor forces. They were also dispersed to victorious soldiers as war booty and to deserving individuals as awards of merit. While individuals could be endowed by the king with up to 19 captives, temples could receive unlimited numbers—some texts refer to bequests of thousands of people. Native and non-native servants intermingled. For native Egyptians, the main pathway to enter the state of slavery was an inability to pay off debt; in many of these cases, the creditor not only took the debtor as a slave, but their families as well. Criminal activities could also result in a life of servitude, often for the convicted and their families both.

Slaves could be employed in domestic activities, such as cooking, brewing, cleaning, or caring for children, or in manual labor, such as farming, making bricks, gardening, or tending the animals. They were sometimes trained in particular crafts as skilled labor, which increased their value, or could be taught to read and write. Some slaves even rose to management positions on their master’s estates. Slaves could be handed down along with other property as part of an inheritance. In general, it appears that slaves assimilated quickly into the local population; they were not viewed as a separate social group. Their legal situation was not always clear, but they were capable of owning land, negotiating transactions, and had the right to private property.

Ensuring Order

Ancient Egyptian society hinged on the king, who ruled by the command of the gods and served as intermediary between the people and the divine. If the king lived in ma’at and fulfilled all his required roles to the satisfaction of the gods, then the land flourished and the people prospered. The ruler and officials who administered the country had clear directives regarding maintaining proper societal function and a specific responsibility to provide for the needs of the entire population. The Egyptians seem to have largely embraced and supported this hierarchy, falling in line with ma’at. Every occupation—whether scribe, potter, soldier, weaver, doctor, or farmer—was believed to play an equally important role in the smooth functioning of society.

Originally published by Smarthistory, 02.27.2022, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.