The ancient history of Gaza reveals a city shaped by its geography and sustained by its adaptability.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Gaza, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, occupies a unique place in ancient history. Situated at the crossroads of Africa and Asia, between the Sinai Peninsula and the Levantine corridor, Gaza served as a critical nexus for trade, culture, and military campaigns. From its earliest Canaanite origins through its role in Egyptian, Philistine, Israelite, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, and Roman contexts, Gaza’s history is a microcosm of the broader ancient Near East. This essay explores the multifaceted history of ancient Gaza from the Bronze Age through Late Antiquity, with particular attention to its political significance, economic prosperity, and religious transformations.

Bronze Age Gaza: Canaanite Roots and Egyptian Hegemony

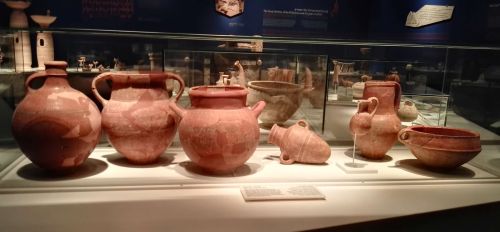

Gaza’s earliest roots can be traced to the Early Bronze Age, beginning around 3300 BCE at Tell es-Sakan, during which it emerged as a Canaanite city of considerable regional importance. Archaeological evidence indicates that the area was settled by Canaanite-speaking Semitic peoples who developed fortified urban centers and engaged in agriculture, metallurgy, and long-distance trade. Gaza’s strategic location at the southern end of the coastal plain of Canaan placed it on the critical overland trade route later called the “Way of Horus,” linking the Nile Delta to the Levant and Mesopotamia. This position allowed Gaza to serve as both a commercial and cultural bridge between Egypt and the Syro-Palestinian corridor. The Canaanite character of Bronze Age Gaza is evident in its ceramic typologies, religious iconography, and language, all of which reflect a West Semitic culture intertwined with Egyptian and Mesopotamian influences.1

By the Middle Bronze Age (circa 2000–1550 BCE), Gaza had become increasingly integrated into Egyptian commercial and diplomatic networks. Egyptian execration texts—inscribed pottery fragments used for ritualistic cursing of enemy cities—list cities in southern Canaan, including Gaza, as objects of Egyptian concern and influence. These texts suggest that Gaza was already perceived as a geopolitical player worthy of notice, if not full control. Egyptian interest in the region was not purely militaristic but also economic; Gaza acted as a key entrepôt for trade in copper, timber, wine, and other goods moving between Egypt and the broader Near East. Excavations at sites such as Tell el-Ajjul, located just south of Gaza and often identified with Bronze Age Gaza or one of its satellite settlements, have revealed imported Cypriot and Egyptian pottery alongside local Canaanite wares, attesting to the area’s international connections.2

Gaza’s incorporation into the New Kingdom Egyptian empire was a defining feature of the Late Bronze Age (circa 1550–1200 BCE). Following the expulsion of the Hyksos from the Nile Delta, Egypt pursued a policy of military expansion into Canaan. Thutmose III’s annals at Karnak record repeated campaigns into the Levant, during which Gaza served as a military base and logistical hub. Egyptian garrisons were stationed in Gaza, and administrative buildings were erected to oversee taxation and the movement of goods and troops. Egyptian control, however, was not total domination; rather, it operated through a system of indirect rule. Local Canaanite elites remained in place, often serving as vassals under Egyptian supervision. The Amarna Letters, a cache of diplomatic correspondence from the mid-14th century BCE, include references to the political instability of the region, with Gaza playing a part in the larger mosaic of city-states vying for influence under Egyptian oversight.3

The religious and cultural landscape of Gaza during this period was a hybrid of Canaanite and Egyptian traditions. Egyptian gods such as Ptah and Hathor appear in archaeological contexts, while native Canaanite deities, such as Baal and Asherah, retained local prominence. Funerary practices also display a blend of cultural traditions, with both Egyptian-style anthropoid coffins and local burial customs coexisting. This syncretism reflected a broader pattern seen throughout Egyptian-controlled Canaan, where imperial influence did not erase indigenous identities but reshaped them through acculturation and selective adaptation. The ruling elite in Gaza likely participated in Egyptian rituals and adopted elements of Egyptian dress and administration as markers of status and legitimacy.4 Such cultural integration bolstered Egypt’s control while simultaneously fostering a uniquely Gazan identity within the imperial framework.

By the end of the Late Bronze Age, Egypt’s grip on Canaan, including Gaza, began to loosen due to internal decline and external pressures. The rise of the so-called “Sea Peoples” around 1200 BCE brought widespread disruption to the Eastern Mediterranean. Gaza, along with many other coastal cities, suffered from the resulting upheavals. Egyptian records from the reign of Ramses III describe battles with these invaders, including the Philistines, who would eventually establish themselves in the region during the subsequent Iron Age. Despite the decline of Egyptian imperial control, the legacy of Bronze Age Gaza remained foundational for its future development. Its role as a center of trade, a node of intercultural exchange, and a locus of imperial ambition had already been firmly established—a pattern that would repeat throughout its ancient history.5

Iron Age Gaza: Philistine Ascendancy and Biblical References

The Iron Age (ca. 1200–586 BCE) witnessed a dramatic transformation in the southern Levant, particularly in Gaza and its surroundings, as the collapse of Bronze Age civilizations ushered in new populations and political realignments. Among the most significant newcomers were the Philistines, one of the so-called “Sea Peoples,” who established themselves along the coastal plain of southern Canaan. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Philistines settled in a pentapolis of major cities—Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath—with Gaza emerging as a critical center of power. This transformation is marked by the appearance of Mycenaean IIIC pottery, new architectural forms, and distinct burial practices, suggesting a complex cultural integration between incoming Aegean populations and the local Canaanite substrate.6 In Gaza, this period saw the establishment of a fortified urban polity that would dominate the southern coastal corridor and play a major role in regional politics and warfare.

Philistine Gaza occupied a vital strategic location along the coastal route connecting Egypt to the Levant and Mesopotamia. Its prosperity in the Iron Age stemmed from its control of trade routes, agricultural production in the fertile coastal plain, and its position as a buffer between the inland highlands and imperial powers such as Egypt and Assyria. Gaza’s harbor allowed it to function as a maritime and overland entrepôt, facilitating the exchange of goods ranging from grain and olive oil to luxury items like ceramics and metals. In this context, Gaza was not merely a Philistine stronghold but a thriving cosmopolitan city whose wealth and location attracted the interest of larger empires and neighboring polities. Material remains from this period—including Philistine bichrome pottery, iron tools, and religious figurines—indicate a fusion of Aegean, Canaanite, and Egyptian influences, pointing to Gaza’s multicultural identity during the Iron Age.7

The Hebrew Bible provides numerous references to Gaza, often portraying it as a symbol of Philistine power and hostility toward Israel. The most famous biblical episode involving Gaza is found in the Book of Judges, where the Israelite judge Samson is imprisoned and ultimately dies in Gaza after collapsing the temple of Dagon (Judg. 16:21–30). This story reflects broader historical tensions between the emerging Israelite tribes and the Philistine city-states during the early Iron Age. Though legendary in character, such narratives are consistent with archaeological indications of conflict between highland and lowland societies. Gaza is also mentioned in the prophetic books, where it is frequently condemned for its participation in the slave trade and violence against Israel (e.g., Amos 1:6–7, Zeph. 2:4). These references suggest that Gaza remained a formidable and adversarial presence throughout much of the Iron Age, representing both the power and perceived moral corruption of the Philistines in Israelite memory.8

Despite the adversarial tone of biblical texts, it is likely that interactions between Israelites and Philistines—including those of Gaza—were complex and included periods of trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. Archaeological discoveries in the broader Philistine region show evidence of Israelite-style pottery and religious artifacts, hinting at periods of coexistence and mutual influence. Gaza, as the southernmost of the Philistine cities and closest to Egypt, may have played a unique role as an intermediary in regional politics. While it maintained its identity as a Philistine city-state, its position may have allowed it to act as a stabilizing force during times of regional upheaval. Moreover, Assyrian records from the 8th and 7th centuries BCE indicate that Gaza was one of the Philistine cities that submitted to Assyrian rule, with rulers such as Hanunu of Gaza appearing in the tribute lists of Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II.9 Such vassalage allowed Gaza to maintain a degree of autonomy and prosperity, even under imperial domination.

By the end of the Iron Age, Gaza’s fortunes, like those of the other Philistine cities, declined significantly due to successive conquests by Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and ultimately Persian forces. The Babylonian conquest of the region in the early 6th century BCE marked the effective end of Philistine political independence. While the biblical tradition and Greek historians such as Herodotus continued to refer to Gaza as a Philistine city, the distinct Philistine culture had largely disappeared by this time, either through assimilation or displacement. Nonetheless, Gaza’s importance as a regional urban center persisted into the Persian period and beyond. The Iron Age had cemented its place not only as a military and economic hub, but also as a symbol of foreign power in Israelite ideology and memory—a duality that would endure throughout antiquity.10

Imperial Overlords: Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians

Gaza’s strategic significance did not wane with the decline of the Philistines. From the 8th century BCE onward, the city found itself under the domination of successive imperial powers, beginning with the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Assyrians, under rulers such as Tiglath-Pileser III, Sargon II, and Sennacherib, sought to control the Levantine corridor as a buffer against Egyptian influence and to secure lucrative trade routes. Gaza, situated at the junction between Mesopotamia and Africa, became an essential node in this system. The Assyrian annals frequently mention Gaza, notably in the account of Tiglath-Pileser III’s campaign in 734 BCE when King Hanunu of Gaza fled to Egypt for support, only to be captured and reinstated as a vassal.11 This episode illustrates the city’s liminal position between competing spheres of influence and its rulers’ diplomatic agility in navigating imperial politics.

Despite its incorporation into the Assyrian imperial structure, Gaza maintained a degree of administrative continuity. The Assyrians often preferred indirect rule, allowing local elites to govern under the supervision of appointed imperial officials. Gaza, like other cities in the region, paid tribute and provided troops but retained its urban hierarchy and religious institutions. Assyrian reliefs and inscriptions, such as those from Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh, underscore the wealth of cities like Gaza and their contributions to the empire in the form of exotic goods and manpower.12 While the Assyrian presence in Gaza was primarily administrative and extractive, there is archaeological evidence suggesting cultural influence as well. Iconography and ceramics from this period show Assyrian stylistic features, especially in luxury items, indicating both the imposition and voluntary adoption of imperial aesthetic norms among Gaza’s elite.13

The fall of the Assyrian Empire at the end of the 7th century BCE gave rise to Babylonian dominance under Nebuchadnezzar II, who sought to consolidate control over the former Assyrian territories, including Gaza. Babylonian hegemony in the region, while less ideologically driven than the Assyrian model, was no less severe in its methods. Nebuchadnezzar’s campaigns against rebellious cities were brutal, and though there is no specific record of a siege of Gaza, its location and history suggest it was likely targeted or at least subjected to tribute demands during these efforts to quell resistance in the Levant.14 Gaza’s political status under the Babylonians was likely that of a semi-autonomous vassal, with local rulers maintaining power contingent upon loyalty to Babylon. The city may have served as a staging ground for Babylonian forces during campaigns into Egypt, reflecting its continued military value.

The transition to Persian rule following Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE introduced a new imperial framework that favored regional autonomy and infrastructural development. Gaza was absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of the satrapy of “Beyond the River” (Eber-Nari), which included much of the Levant. The Persian administration emphasized efficient communication and trade, both of which benefited Gaza. The city likely prospered under Persian rule, becoming a key station along the Royal Road and facilitating commerce between Egypt, Arabia, and the Persian heartland.15 Although direct archaeological evidence from Persian-period Gaza is limited, references in Greek sources such as Herodotus and later in Aramaic documents from Elephantine indicate the city’s continued vitality and integration into imperial systems.16 The Persians tolerated local religions and governance structures, allowing Gaza’s population to retain a measure of cultural distinctiveness while participating in the broader imperial economy.

By the close of the Persian period in the 4th century BCE, Gaza had endured and adapted through centuries of foreign domination. Its geographic location ensured that no empire could ignore it, yet its survival also depended on the pragmatism of its rulers and population. While each imperial regime imposed distinct political and economic structures, Gaza’s civic institutions, religious life, and strategic value allowed it to weather these changes with resilience. The city’s role as a frontier hub—between Mesopotamia and Egypt, East and West, desert and sea—ensured its continuous relevance. From Assyrian domination to Babylonian control and Persian integration, Gaza exemplifies the complex local responses to imperial power in the ancient Near East, blending resistance, collaboration, and cultural negotiation into its urban history.17

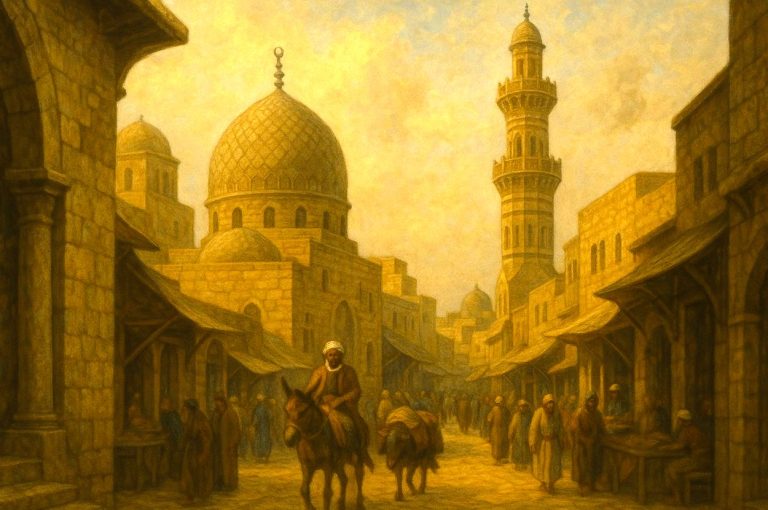

Hellenistic Gaza: Greek Culture and Conflict

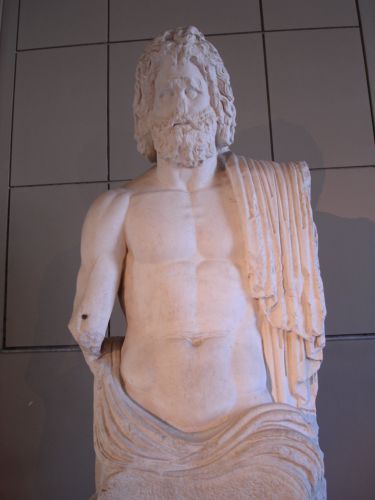

The conquest of the Near East by Alexander the Great in the late 4th century BCE marked a new epoch in Gaza’s history, ushering in the Hellenistic period characterized by the diffusion of Greek language, culture, and political systems. Gaza, strategically situated near the Egyptian border and the trade routes of the southern Levant, was among the last cities to fall to Alexander in his march toward Egypt. In 332 BCE, Alexander besieged Gaza for several months, encountering fierce resistance from the city’s defenders under the Persian-appointed Arab governor Batis. The protracted siege ended with Alexander breaching the city’s defenses and executing Batis, reportedly by dragging him behind a chariot in emulation of Achilles’ treatment of Hector—a symbolic act reinforcing the Hellenizing vision of the Macedonian conqueror.18 Gaza’s stubborn resistance earned it harsh retribution but also signaled its geopolitical significance in the eyes of the new imperial overlords.

Following Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his generals—known as the Diadochi—vied for control over his fragmented empire. Gaza, like much of the Levant, became a contested space between the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria. Initially absorbed into the Ptolemaic realm, Gaza was administered as part of the coastal province of Coele-Syria and enjoyed a degree of prosperity due to its role as a commercial hub linking Egyptian grain, Arabian incense, and Mediterranean goods. The Ptolemies invested in civic institutions and infrastructure, promoting Hellenistic culture while co-opting local elites. Gaza likely saw the construction of gymnasia, theaters, and other public buildings in the Greek style, though few survive archaeologically due to later urban development.19 This period marked the beginning of Gaza’s gradual transformation into a Hellenized polis, complete with Greek education, language, and art, layered atop a Semitic cultural substrate.

By the second century BCE, Gaza increasingly became a flashpoint in the conflict between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties. The Seleucid king Antiochus III seized Gaza during his campaign to wrest control of Coele-Syria from the Ptolemies in 200 BCE, as recorded in both Greek sources and the books of Maccabees.20 Under Seleucid rule, Gaza’s Hellenistic character deepened, although it remained a multiethnic city with diverse religious and cultural expressions. The presence of Greek settlers and soldiers introduced new cults and artistic forms, while older Semitic traditions persisted, resulting in a unique cultural synthesis. The Seleucids’ promotion of Greek civic institutions, including the elevation of Gaza’s political status, encouraged the assimilation of Greek norms among the city’s elites. Nevertheless, this cultural shift was not universally accepted and likely produced tensions between traditionalist and Hellenized factions within Gaza’s population.

One of the defining features of Hellenistic Gaza was its complex relationship with the Jewish populations of the region. While Gaza was not part of Judea proper, it was geographically and politically entangled in the Hasmonean revolt and subsequent Maccabean wars against Seleucid authority. In 96 BCE, the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus besieged and destroyed Gaza, accusing its population of anti-Jewish sentiment and hostility during earlier conflicts.21 This dramatic episode marked a rupture in the city’s history, interrupting its Hellenistic trajectory and illustrating the volatility of cultural and ethnic coexistence in the region. Gaza’s destruction under Jannaeus was not simply a military act but a symbolic assertion of Judaean power over a city long associated with foreign rule and Hellenistic values. Although the city was later rebuilt, its status as a Greek polis was temporarily eclipsed by the realities of regional power struggles and rising ethnic nationalism.

Despite these upheavals, Gaza remained a vital urban center into the late Hellenistic period. By the first century BCE, it had regained much of its former importance and was eventually incorporated into the Roman sphere of influence. Its enduring vitality rested on its strategic location, diversified economy, and capacity to adapt to changing political circumstances. The Hellenistic legacy in Gaza—manifested in its institutions, artistic production, and linguistic environment—would continue to shape the city well into the Roman period. Gaza’s experience under the Hellenistic empires reflects the broader dynamics of cultural negotiation, resistance, and adaptation that characterized the eastern Mediterranean in this era of empire. Far from being passively Hellenized, Gaza was an active participant in crafting a new civic identity at the crossroads of Greek, Semitic, and imperial traditions.22

Roman and Byzantine Gaza: Economic Golden Age and Christianization

Under Roman rule, Gaza entered a period of remarkable economic prosperity and cultural development. Following Pompey’s eastern campaigns in 63 BCE, Gaza was integrated into the Roman province of Syria and later, after administrative reforms, into the province of Palaestina Prima. The Romans recognized Gaza’s strategic location at the terminus of important trade routes connecting Arabia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean. Its port, Maiumas, facilitated the export of incense, textiles, and agricultural products, especially wine, which became Gaza’s signature commodity.23 Gaza wine was highly prized throughout the empire, as evidenced by amphorae bearing its stamps found across the Mediterranean, from Gaul to the Black Sea. This economic success financed the embellishment of the city with colonnaded streets, theaters, baths, and marketplaces that reflected the grandeur of Roman urbanism.

By the second and third centuries CE, Gaza had become one of the wealthiest cities in the Levant. Roman civic institutions, including a council (boule) and assembly (demos), allowed local elites to participate in governance while aligning with imperial authority. Gaza’s intellectual life flourished during this period, with rhetorical schools attracting students from across the empire. The most famous among these was the school of Procopius of Gaza, who, in the early sixth century, would become a leading figure in the rhetorical and theological life of the city.24 These schools were centers of both classical Greek education and, increasingly, Christian philosophy, reflecting the city’s transitional status as a Hellenized Roman city gradually becoming a Christian one. The coexistence of pagan and Christian institutions created a complex social tapestry, though one that would shift decisively with imperial support for Christianity.

Christianization of Gaza was a gradual and, at times, contested process. Although Christianity had taken root in nearby regions by the third century, Gaza remained a stronghold of paganism well into the fourth century. The city’s temples, particularly the great temple of Marnas (the local god of rain and grain), were famous throughout the region.25 The persistence of traditional religion in Gaza led to conflict with the growing Christian population, especially after Emperor Constantine’s conversion and subsequent policies favoring Christianity. In the late fourth and early fifth centuries, Gaza’s bishops—most notably Porphyry—campaigned vigorously for the destruction of pagan shrines and the construction of Christian churches. With support from Empress Eudoxia and Emperor Arcadius, Porphyry succeeded in closing and demolishing the temple of Marnas around 402 CE, symbolizing the definitive triumph of Christianity in Gaza.26 This event was accompanied by the rededication of urban space to Christian purposes, transforming the city’s religious and architectural landscape.

The Byzantine period saw Gaza reach the height of its cultural and religious prestige. With the collapse of organized paganism, Gaza became a prominent center of Christian scholarship, liturgy, and ecclesiastical politics. The city produced several notable Christian intellectuals and poets, such as Choricius of Gaza, whose works reveal the persistence of classical forms within a Christianized framework.27 Public buildings and basilicas were adorned with elaborate mosaics, inscriptions, and iconography that reflected Byzantine theological themes. Archaeological discoveries, including the mosaic floors of the Church of St. Stephen and the Gaza synagogue (converted to Christian use), attest to the city’s vibrant religious life and artistic production. The shift from pagan to Christian Gaza was not merely one of belief but of civic identity, as the city redefined itself within the orbit of the Christian Roman Empire.

However, this golden age would not last indefinitely. The Persian invasions of the early seventh century, followed by the Arab-Muslim conquest around 637 CE, marked the end of Gaza’s status as a major Byzantine Christian city. Nevertheless, the Roman and Byzantine centuries left an enduring legacy on Gaza’s urban fabric, religious traditions, and cultural memory. The city’s transformation from a pagan Greco-Roman center to a bastion of Christianity illustrates the broader shifts within the eastern Mediterranean world. Gaza’s experience encapsulates the dynamism of late antiquity: a period of flourishing intellectual life, economic integration, and profound religious change.28

Conclusion

The ancient history of Gaza reveals a city shaped by its geography and sustained by its adaptability. From its early Canaanite foundation through centuries of imperial domination and cultural transformation, Gaza served as a vital node in the ancient Near East. Its story is one of continuity amid change—a city both besieged and celebrated, conquered and cosmopolitan. Whether under Egyptian pharaohs, Philistine lords, Assyrian kings, Persian satraps, Greek generals, Roman governors, or Christian bishops, Gaza remained a critical and dynamic player in the historical narrative of the ancient world.

Appendix

Endnotes

- William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 71–75.

- Peter M. Fischer, Tell el-‘Ajjul: The Middle Bronze Age Pottery (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2006), 14–22.

- William L. Moran, ed. and trans., The Amarna Letters (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), EA 287–290.

- Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 BCE (New York: Doubleday, 1990), 254–259.

- Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 139–147.

- Trude Dothan and Moshe Dothan, People of the Sea: The Search for the Philistines (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 122–135.

- Gitin, “Philistines in the Books of Kings,”, 273-286.

- K. Lawson Younger Jr., A Political History of the Arameans: From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2016), 41–47.

- Finkelstein and Mazar, The Quest for the Historical Israel, 165-171.

- Lester L. Grabbe, Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? (London: T&T Clark, 2007), 213-219.

- Hayim Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria: Critical Edition with Introductions, Translations, and Commentary (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), 142–145.

- Eckart Frahm, A Companion to Assyria (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017), 439–441.

- John Malcolm Russell, The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1999), 91–93.

- Grabbe, Ancient Israel, 134-136.

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), 754–756.

- Herodotus, Histories, 3.5–6; Bezalel Porten, Archives from Elephantine: The Life of an Ancient Jewish Military Colony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 134–137.

- Amélie Kuhrt, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period (London: Routledge, 2007), 268–272.

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 2.26; Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great (London: Penguin, 1973), 255–257.

- Günther Hölbl, A History of the Ptolemaic Empire (London: Routledge, 2001), 123–125.

- 1 Maccabees 10:80–89; Polybius, Histories, 16.18; Bezalel Bar-Kochva, The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 184–186.

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13.13.3; Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World (London: Routledge, 2003), 41–43.

- Erich S. Gruen, Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 71–75.

- Peter Fibiger Bang, The Roman Bazaar: A Comparative Study of Trade and Markets in a Tributary Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 171–173.

- Robert J. Penella, The Rhetoric of Praise in the Greek Inscriptions of the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 96–99.

- Glen W. Bowersock, Hellenism in Late Antiquity (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 39–40.

- Mark the Deacon, Life of Porphyry of Gaza, trans. G.F. Hill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913), 65–67.

- Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, AD 395–700 (London: Routledge, 2011), 128–130.

- Hugh Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In (Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2007), 81–82.

Bibliography

- 1 Maccabees. In The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Arrian. Anabasis of Alexander. Translated by P.A. Brunt. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Bang, Peter Fibiger. The Roman Bazaar: A Comparative Study of Trade and Markets in a Tributary Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel. The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Bowersock, Glen W. Hellenism in Late Antiquity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990.

- Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

- Cameron, Averil. The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, AD 395–700. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Cline, Eric H. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001.

- Fischer, Peter M. Tell el-‘Ajjul: The Middle Bronze Age Pottery. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2006.

- Fox, Robin Lane. Alexander the Great. London: Penguin, 1973.

- Frahm, Eckart. A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

- Grabbe, Lester L. Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? London: T&T Clark, 2007.

- Gruen, Erich S. Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Hölbl, Günther. A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. Translated by William Whiston. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2007.

- Kuhrt, Amélie. The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Mark the Deacon. Life of Porphyry of Gaza. Translated by G.F. Hill. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

- Mazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 BCE. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

- Moran, William L., ed. and trans. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- Penella, Robert J. The Rhetoric of Praise in the Greek Inscriptions of the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Polybius. The Histories. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Porten, Bezalel. Archives from Elephantine: The Life of an Ancient Jewish Military Colony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

- Russell, John Malcolm. The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1999.

- Schäfer, Peter. The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander to the Arab Conquest. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Tadmor, Hayim. The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria: Critical Edition with Introductions, Translations, and Commentary. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.