A rationale for studying the origins of the prehistoric state in Greece.

By Dr. Jack L. Davis

Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology

University of Cincinnati

Introduction

Once defined as an archaeological culture, Mycenaeans played an important role in combatting the ideas of those who argued that there had been a break in continuity between modern and ancient Greece. At the same time, Greek prehistory in Greece and abroad found a comfortable home in the field of Classics, which broadly embraced a phylogenetic narrative of the past.

Most American university courses concerned with the origins of the state focus on so-called primary or pristine states, areas of the world where civilizations—ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Mesoamerica, or China—supposedly arose independent of external influences. Prehistorians recognize that the general processes that led to state formation were very much the same everywhere in the world.1 States in Greece, however, are considered to be secondary states and often imagined to have come into existence in response to contact with the primary states of the Middle East and Egypt.2

Why then study the origins of early states in Greece? Greece (130,000 sq km) is small in comparison to Mesopotamia (500,000 sq km), modern Egypt (1 million sq km), or modern China (9.5 million sq km), much smaller even than the Mayan heartland in Mesoamerica (390,000 sq km) (see map 1). But within this small area, the quantity and quality of relevant archaeological data is staggeringly great, accumulated both through excavations and surface surveys, and the potential for learning more about state origins is correspondingly high. In Greece, projects have been sponsored by the Greek Ministry of Culture, Greek universities, Greek private institutions (notably the Archaeological Society at Athens), and foreign schools of archaeology in Athens.3 Since the 1980s, a virtual avalanche of relevant information has accumulated in direct response to generous funding from the New York–based Institute for Aegean Prehistory and in association with development programs co-funded by Greece and the European Union.4

The road to social complexity in Greece was long and winding—despite considerable evidence for contact with the Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Although some have argued for an indigenous origin of agriculture in the Balkans, it is now generally accepted that major grains and domesticated animals reached Greece from the Near East. Evidence points to the transmission of these essentials for a Neolithic (New Stone Age) lifestyle already in the seventh millennium B.C., yet the state in Greece emerged only after 2000 B.C.—in contrast with Egypt and Mesopotamia, where such developments took place in the fourth millennium B.C. What explains the lag? What broke the inertia two thousand years later, on Crete ca. 1900 B.C. and then on the Greek mainland ca. 1600 B.C.? Social complexity in Mainland Greece moved in fits and starts, more so than in Crete, where a steady pace led to the emergence of the Minoan civilization earlier than the Mycenaean.

Blegen as Sather Professor

It seems uncontroversial to me why the emergence of Mycenaean civilization should be of interest to anthropologists, but it is perhaps less clear why readers who come from a background in Classical languages and literature should care about the topic. Why would the University of California’s faculty of Classics invite me to Berkeley? After all, the Sather Professor holds the Sather Professorship of Classical Literature, not archaeology, let alone Greek prehistory.

The very first Sather Professor, J. L. Myres of Oxford, was, nonetheless, deeply interested in earliest Greece and collaborated with Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of the Palace of Minos at Knossos, in an attempt to decipher the Linear A script of the Minoan civilization (see figure 1). Other Sather professors of the earlier twentieth century shared Myres’s interest in Greek prehistory. They included Martin Nilsson, who explored Mycenaean mythology; Axel Persson, who lectured on Bronze Age Greek religion; and Blegen himself. Clearly the Greek Bronze Age has always been a significant, if intermittent, component of the Sather Lecture series. How-come this was the case? What has more generally been the role played by Greek prehistory in Classics over the past century?5

To answer these questions requires an understanding of the developmental history of the discipline of Greek prehistory and the role that Blegen played in it prior to World War II. Blegen came to Berkeley as Sather Professor in 1942, an impossible year for Britain. Germany had been systematically bombing London since September 1940, and a naval blockade had begun earlier. Sir John Beazley, who had accepted the Sather Professorship for 1941–42, was stuck in Oxford. Berkeley had a problem—and an impromptu solution was found. The duties of the Sather Professor that year were divided between Harold Cherniss and Blegen.6

It is easy to see why Berkeley called on Cherniss. Both he and his wife were University of California alumni. Although teaching at Johns Hopkins, Cherniss held a Guggenheim fellowship that year and was free to travel. Blegen, whose first language was Norwegian, was probably tapped through the intervention of Axel Persson, Sather Professor for 1941. In a letter to Blegen in Swedish, archived at the University of Cincinnati, Persson addressed him as “Dear Friend” and described his own presentations before he had returned to Sweden via the Far East (he was already expecting proofs of his The Religion of Greece in Prehistoric Times, Sather Classical Lectures 17).7

Predictably, Blegen spoke at Berkeley about his campaigns at Troy and his more recent discovery of the Palace of Nestor. But also of interest is an informal public discussion he led while at Berkeley. According to the Daily Californian, Berkeley’s independent, student-run newspaper, Blegen described the Greeks as a “courageous people, universally admired for their determined stand in defense of their country” against Mussolini and Hitler. In 1939 he had written his sister that both dictators “deserved to be boiled in oil.” The Greeks, in his mind, were clearly special, having stood up to the determined onslaught of the Axis powers. Blegen’s belief in the exceptional nature of the Greek character also pervaded and colored his views about Greek prehistory, as well as those of his contemporaries.

In reference to the Greek Bronze Age and the Mycenaean civilization, Michael Fotiadis has written that “the phantasy we inherited . . . has become the ideology that sustains our practice today.”8 And Blegen is as responsible for this situation as anyone. Unlike early complex societies in the Middle East and Egypt, which were literate, Bronze Age Greece is largely the creation of archaeology—a fact that has over the past 150 years made the field particularly susceptible to manipulation by forces of nationalism, especially but not exclusively those exerted by the modern Greek nation-state. Understanding this phenomenon requires inspection of certain foundational documents of Greek prehistory composed by Blegen and his closest friend and colleague Alan Wace.

In 1941 the University of Pennsylvania published the text of a lecture that Blegen presented within the framework of its bicentennial celebration.9 The text is important in that in it, Blegen, a man who rarely wandered far from descriptive prose, allowed himself to speculate. In so doing, he provided a charter for the inclusion of Greek prehistory within programs of Classics in his day. Blegen emphasized the following four points:

- “Mycenaean civilization . . . maintained its existence some three hundred years, during which a slow progressive decline is manifest both on the material and artistic sides.”

- The Mycenaean palaces (and Troy) were all destroyed at more or less the same time by fire, as the result of an external attack by the Dorians.

- “Mycenaean culture was not completely obliterated. . . . It may safely be concluded that some part of the earlier inhabitants survived” and merged with the racially akin Dorian stock.

- “By the end of the 10th century the amalgamation was virtually complete, and the Hellenic race had emerged ready to commence its creative role in cultural history.”

He concluded:

The race was now a distinctive one, unified and sharply differentiated from those outside the pale; and the constituent elements of the blend are of course no longer recognizable. If one is familiar with the earlier archaeological material, however, one may indulge in some harmless speculation regarding the particular sources of some of the outstanding traits of the Greek character.

What were those outstanding traits?

- “superstition, coarseness, and occasional unbridled passion and cruelty,” inherited from those occupying Greece in the Neolithic.

- “delicacy of feeling, freedom of imagination, sobriety of judgment, and love of beauty” from those who had arrived in the Early Bronze Age and “whose greatest achievement” was the creation of the Minoan civilization.

- “physical and mental vigor, directness of view, and that epic spirit of adventure in games, in the chase, and in war,” attributable to the Aryan blood of the Mycenaean and Dorian population.

Cultural and political “divisions” in historical times are explained as differences in the proportions of racial blending represented in a given population and the speed at which that process took place. Blegen uses a metallurgical simile according to which “a similar alloy was everywhere purified and hardened during those later centuries of Aryan accretions, culminating in the pouring of the Dorian flux.”10

Blegen himself was the product of blended cultures. His father had immigrated from Norway to the U.S. in 1869, where he studied in Minneapolis and later taught Greek. By 1908 young Carl had acquired a B.A. from Yale, his third, and, as a graduate student, continued to study Latin and Greek. It was at Yale that he also decided to attend the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) in 1910. In Athens at the ASCSA, under the mentorship of director Bert Hodge Hill, Blegen made decisions that would shift the focus of his research from literary and philological studies to prehistory and archaeology.11

For his doctoral degree, he began in 1915 to excavate Korakou, where he learned British techniques of stratigraphical excavation from Wace. Wace also schooled Blegen in the typology of prehistoric pottery, so critical for relative dating. Korakou: A Prehistoric Settlement near Corinth, his published dissertation, provided scholars for the first time with a clear outline of the prehistory of the entire Bronze Age in southern Greece.12

Blegen’s evolutionary picture of the Greek Bronze Age must have influenced philologist William T. Semple’s decision to hire him to teach students about prehistoric Greece at the University of Cincinnati and to conduct excavations on behalf of his Department of Classics. Semple’s newly founded department was being built so as to fit into the phylogenetic model of Greek history popular at the turn of the twentieth century.13 In fact, by the time Blegen arrived as a student in Athens, few, if any, serious scholars doubted that ancestors of the modern Greeks had created the Mycenaean civilization. Schliemann’s finds at Mycenae already lay a quarter century in the past and had transformed views about Pre-classical Greece.

Scholars of prehistoric Greece before Schliemann, in the 1860s and early 1870s, had been concerned with artifacts from eras that, because of their temporal remoteness, had left no traces in later Greek written sources. They sought to incorporate Greece into European prehistory by documenting a Greek Stone Age, imagining that primitive lake dwellers had lived in Greece, as they had in Switzerland. The Cyclopean walls of the Argolid around Mycenae and Tiryns, constructed of massive, roughly hewn blocks, were thought to be Pelasgian, built by a pan-Mediterranean pre-Greek population—a proposition encouraged by Petit-Radel’s 1841 Monuments Cyclopéens, a commentary on models in the Pelasgian Gallery of Paris’s Mazarin Library.14

But after Schliemann’s discoveries, it was Mycenaeans full steam ahead, not Pelasgians. At Korakou, Blegen began to explore the “nameless τις of the Homeric poems.”15 The Greek past was being pushed back into what had previously been a European prehistory, and young Blegen’s mission was to marshal evidence for the continuity of the Greek people. He had committed himself to the nationalist project of the Greek state, a campaign in hyperdrive in his day in reaction to a critique by Jacob Fallmerayer, who in 1830 had written:

The race of the Hellenes has been wiped out in Europe. Physical beauty, intellectual brilliance, innate harmony and simplicity, art, competition, city, village, the splen-dour of column and temple—indeed, even the name has disappeared from the surface of the Greek continent. . . . Not the slightest drop of undiluted Hellenic blood flows in the veins of the Christian population of present-day Greece.16

Fallmerayer argued that the Greeks had deliberately misled European elite. Michael Herzfeld has described the forceful Greek response:

The very name of Fallmerayer has been execrated in Greece from 1830 until our own time. . . . That execration, however, was extraordinarily productive, for Fallmerayer flung down a challenge which the Greeks could ill afford to ignore; and they met it magnificently. . . . Fallmerayer’s crime consisted in denying them descent from the ancient Hellenes.17

Blegen never questioned the logic of this “magnificent” Greek defense and viewed the study of the Greek Bronze Age by philhellenes like himself as a means by which foreigners could participate, through archaeology, in the process of Greek nation building. But Blegen was also committed to political action. He fully supported the irredentist platform of Prime Minister Venizelos and his party, the so-called Grand Idea (Μεγάλη Ιδέα) that Greece should capture former territories of the Byzantine Empire. In 1919 he was an asset of the Greek intelligence service in Bulgaria, where he gathered data on the Greek minority. And in 1920 he tacitly approved the Greek annexation of western Turkey by initiating excavations at Colophon, in the Greek zone of occupation.18

By 1930 Blegen had published two articles that cemented his reputation as a pre-eminent prehistorian: “The Pre-Mycenaean Pottery of the Greek Mainland” (1918) with Wace, and “The “Coming of the Greeks” (1928) with J. B. Haley. According to Blegen and Wace, the cultures of Crete, of the Greek islands, and of the Greek mainland were all “branches of one great parent stock which pursued parallel, but more or less independent courses [while] the Mycenaean civilization is the fruit of the Cretan graft set on the wild stock of the mainland.”19

Wace and Blegen’s ideas fell on fertile ground, sprouted, and blossomed—welcomed by an audience well-prepared for the narrative they were writing. Long before the 1870s, there had been an interest in the ruins of Mycenae because of its central role in ancient Greek literature as Agamemnon’s seat. In the fifteenth century Cyriacus of Ancona had searched for it unsuccessfully, but a hundred years later the Venetians knew exactly where Mycenae lay. Francesco Vandeyk, an engineer, produced a map of the Argolid in 1700, described the ruins of Mycenae in detail, and may even have uncovered the Lion Gate. A 1703 account by Alessandro Pini, a Florentine doctor in the service of Venice, explicitly links the ruins to the Homeric epics—and through them to the ancestors of the historical Greeks. He wrote:

Among the ruins, which exist at present, there is a very majestic and large cupola, but full of earth. Anyone who has even a little knowledge recognizes it as a grave, and it is not unlikely that it is the Tomb of Agamemnon, as described by Pausanias.20

Blegen and Wace’s orthodoxy owed much to the views of the Greek archaeologist Christos Tsountas. Tsountas’s ideas had been promulgated in the Anglophone world through his book The Mycenaean Age: A Study of the Monuments and Culture of Pre-Homeric Greece (1897), a translation of an earlier work in Greek. The noted biblical scholar, George Goodspeed of the University of Chicago, empha-sized that Tsountas was writing Greek history:

We may be said now to possess a new chapter, or rather several new chapters, of early Greek history, about which we are better informed than concerning several later chapters, even that which has to do with Homer himself.21

The Greek Bronze Age was welcomed into the curricula of departments of Classics, particularly those that embraced the broad Altertumswissenschaft (science of antiquity) perspective. The idea of a Homeric archaeology, drawing on Mycenaean discoveries, had also emerged in Germany with the appearance of Wolfgang Reichel’s Homerische Waffen (1901). By the turn of the century, outside Germany, it had infected influential philologists such as Walter Leaf, who, in 1900, included an appendix on Homeric armor in his edition of the Iliad (1900).

Tsountas’s influence can hardly be exaggerated.22 He declared the Greekness of Mycenaean culture six decades before Michael Ventris deciphered the Linear B script and confirmed that the administrative language of the Mycenaean palaces was Greek.23 Tsountas imagined that Mycenaean culture resulted from an indigenous evolution that reached back to the Neolithic, where he believed that he had documented precedents for the Homeric palace-hall in his excavations at Dimini and Sesklo near Volos in Thessaly. In so arguing, he was incorporating an archaeologically based prehistory within the 1885 narrative of ethnic continuity composed by the Greek nationalist historian Constantine Paparrigopoulos.24

Blegen remained dedicated to that same narrative until the end of his life, and because of his diplomatic service in Greece after World War II, his opinions were even sought outside the narrow field of Greek archaeology. A continued adherence to the Greek national project is clear from his (unpublished) book “The United States and Greece,” written for the American Foreign Policy Library.25 In it, he writes:

There is no doubt that in the people of modern Greece we must recognize the descendants of the ancient Greeks; and certainly there are few, if any, other races that can show so long a history of continuous national existence, contrary to the theory advanced by Fallmerayer.26

According to Blegen, under the Ottoman Empire, the Balkans were occupied by “peoples with a motley pattern of distribution”; new nation-states “in their infancy” retained elements of the Ottoman pattern, “almost inextricably mixed in their population”; and this “confusion” was “largely cleared away” through “far-sighted agreements for the exchange of minorities.” He speaks, furthermore, of the Greek race’s “astonishing power to absorb and assimilate alien elements that from time to time established a foothold on Hellenic soil.”27

The decipherment of Linear B as Greek in 1952, hastened by Blegen’s discovery of the archives of the Palace of Nestor in 1939, came as no particular surprise to the fathers of Greek prehistory. Blegen in 1954 could write to Wace,

“Many thanks . . . for the copy of your bilge on ‘The Coming of the Greeks.’ I have read it with much interest and of course am in full general agreement with the views you express. In the main it is just what we’ve been thinking and saying for years on the basis of the archaeological evidence, before the clinching linguistic evidence was available.”28

Wace’s article to which Blegen referred read:

Thus since the inhabitants of Greece in the Classical Period were Greeks and spoke and wrote Greek, we can only conclude that the time of their arrival in Greece was the Middle Bronze Age. In other words, the new race with a new culture which entered Greece at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age was the Greek race, the first Hellenes to come to Greece. Other waves of Greek speaking peoples like the Dorians probably came into Greece at different dates in later times, but the Middle Helladic people were the first Greeks. . . . The substance of this archaeological argument is that the Mycenaeans of the Late Bronze Age would have been Greeks and would have spoken and written Greek. The Mycenaean culture therefore is the first manifestation of Greek art and civilisation.29

But what of the term Mycenaean as an identity attached to a particular people? Before Schliemann, the adjective Mycenaean had been used in Western languages only to describe the residents of ancient Mycenae, the earliest attestation in English being a Renaissance commentary on Diodorus Siculus, a historian of the first century B.C.: “This lyon . . . resortyd moche emonge the Micenyens, bitwene theym and the grete wode callyd Nemea.”30 Schliemann applied the term to categories of artifacts from his excavations: “Mycenaean idols” or “Mycenaean metals.”31 It was used more broadly by German Classical archaeologists Adolf Furtwaengler and Georg Loeschke when they published their monumental Mykenische Vasen in 1886—the first steps toward defining a “Mycenaean” style of vase painting. By the mid-1890s French archaeologist Georges Perrot and art historian Charles Chipiez were speaking of “l’art mycénien.”

Tsountas and J. Irving Manatt, a professor at Brown University who had translated The Mycenaean Age from the Greek, would write in English in 1897 of the “Mycenaean Age,” of the “second decade of Mycenaeology,” while using “the Mycenaeans” both in reference to the prehistoric and historic residents of Mycenae. “The” Mycenaeans is applied there in every sort of context, from discussions of the prehistoric economy to social organization, religion, warfare, and craftsmanship. For the most part, Tsountas and Manatt used “the Greeks” to emphasize contrasts and to make comparisons with “the Mycenaeans,” but they also speak of “the Mycenaean Greeks” and wonder which “race or races among the Greeks known to history [is it] to whom the achievement of Mycenaean civilization is to be ascribed?”32

It was Tsountas’s use of the terms μυκηναίος and μυκηναίοι five years earlier that had popularized the extension of the term Mycenaean to refer to peoples of the Late Helladic period.33 He certainly hoped that it would:

As the outcome of all these discoveries and the studies based upon them, there stands revealed a distinct and homogeneous civilization, a civilization so singular in many aspects that scholars have been slow to see in it an unfolding of Hellenic culture. At first, indeed, it was pronounced exotic and barbarous. . . . While other terms (as Achaean and Aegean) have been proposed, it seems desirable for the present to adhere to that name for this civilization which is at once suggested by its earliest known and (so far as yet ascertained) its chief seat, Mycenae. And to the authors and bearers of this civilization throughout Greece, we must apply the same term Mycenaean.34

The director of the Hermitage, Ludolf Stephani, had been one of the scholars slow to see in Mycenaean finds an unfolding of Hellenic culture. Stephani reasoned that Schliemann’s finds had been buried at the time of the Herulian invasion of Greece in the third century after Christ. Wolfgang Helbig of the German Archaeological Institute was another doubting Thomas; he had argued in 1895 that Mycenaean art was the creation of Phoenician craftsmen.35

Only rarely, however, has anyone tried to unpack the term Mycenaean, and then with little conviction. Lord William Taylour, who directed British excavations at Mycenae in the later 1950s and 1960s, comments in The Mycenaeans: “‘The Mycenaeans’ is not a designation that will be found in the Classical authors.”36 He asks who were the people who created the Mycenaean civilization:

“It was grudgingly admitted that they were ancestors of the Greeks, but how Greek were they? What is certain is that through its entire history Greece has been subject to the influx of foreign peoples, more often coming with hostile intent.”37

He concludes, however, that the origins of the “Greek miracle” lay in the Bronze Age and celebrates, as had Blegen in 1947, the ability of Greek culture to absorb foreign elements.

The Lamarckian concept of cultural evolution that pervades the foundational documents of our field was founded in racial and racist concepts, even as is Taylour’s question “How Greek were they?” The notion that Greek culture had a remarkable superpower to create an amalgam from diverse peoples that would trigger accomplishments a half millennium later must arouse suspicion.

Even after Schliemann’s discoveries, not all would agree with Tsountas, Blegen, and Wace as to the relevance of Greek prehistory to the larger field of Greek studies. Already in 1911 Professor Percy Gardner, president of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, addressed his membership in London:

Another kind of expansion of Greek Archaeology has also been notable in the last thirty years. A strong tendency towards a research into origins set in with the rise of Darwinism in the mid-Victorian age. . . . The chasm dividing prehistoric from historic Greece is growing wider and deeper; and those who were at first disposed to leap over it now recognize that such feats are impossible. We shall all be disposed most heartily to welcome the spread of knowledge in regard to primitive and prehistoric Greece. It is a fresh breeze to fill our sails, and fresh point of view whence to approach the subjects which so deeply interest us. Yet I hope you will allow me on the last occasion on which I shall thus address you, to express my own preference for what is purely Greek.38

So what does the field of Classics gain from study of the Greek Bronze Age?

Greek Prehistory and Classics

Finally, we turn to the relationship between the study of Greek prehistory and the field of Classics today. Once the nationalist agenda that chartered Greek prehistory within Classics is removed, as it should be, what is the rationale for continuing to teach Greek prehistory within a Classics environment?

Τhe recent publication of a two-volume collection of papers titled A Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean hints at one answer.39 Contributors were invited explicitly to consider the debt (if any) to the Bronze Age of Classical city-states. William Cavanagh, in his essay on Sparta, states his own agenda clearly (and it is that of others too):

Opinions about the inheritance from Mycenaean to Archaic Greece has swung from a view that the culture of the 14th–13th centuries deeply influenced what was to follow in the 8th–6th centuries to a view that a deep gulf separated the two. The Iliad and the Odyssey have been seen by some as a window on the Bronze Age, by others as a reflection of the time the poems were put together, centuries later. The nature of their creation is hotly contested: are they each the vision of one great poet or constantly reshaped by a fluid oral tradition? Their central theme, the Trojan War, has been reconstructed as a seminal historical clash or alternatively as a powerful myth but not a real event.40

Cavanagh concludes that, among other things, the nature of the Spartan historical settlement pattern, the cluster of villages that constituted Sparta itself, perioikic (non-Spartan) communities, and a general sense of Spartan identity had emerged already in the Mycenaean period. He even suggests that the origins of the Spartan system of holding a subject population in thrall, helotry, might be traced back to the fall of the Mycenaean palaces and the dispersion into hinterlands of dependent labor forces.

In Pylos there also had been a very large community around the Palace of Nestor, including slaves. We have just enough finds in and around the ruins of the palace and elsewhere to know that that particular area was never totally deserted. In the main, however, the population would likely also have survived the fall of the palace, as in Laconia, dispersed elsewhere or invisible to us as archaeologists. This invisibility had already been the case in the Late Bronze Age, when only a fraction of the population seems to have had access to formal burial in tholos or chamber tombs. It was the elite culture that had been so obtrusive in the landscape, with their monumental burials, the buildings on the acropolis, and the ceramic production that we know the palace sponsored in the thirteenth century B.C.

In A Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean, Sharon Stocker and I explicitly considered the aftermath of Mycenaean Pylos. The Archaic period did not begin as a tabula rasa in Messenia, and we concluded that a memory of a united Mycenaean kingdom surely remained, passed from generation to generation. Such traditions were likely strongest in places that had been integrated into a common polity the longest, such as the Hither Province of Nestor’s realm. It was also there, north of the Bay of Navarino, that associations with Nestor were preserved in Classical times at the Cave of Nestor and at the Tomb of Thrasymedes, Nestor’s son, mentioned by the traveler Pausanias in Roman times.41 If cult practice also played a role in transmitting memories from the Bronze Age to historical Messenians, this does not, however, appear to have happened at the site of the former Palace of Nestor itself, but nearer the coast where an early sanctuary of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, has been recently discovered.42

So too for the Further Province—aspects of its Mycenaean background may have played a role in conditioning its historical development. Classical Thouria, on the outskirts of the modern metropolis of Kalamata, seems to have been the capital of the Further Province.43 This settlement sat in a position critical for communications between Messenia and other parts of the Peloponnese through Laconia, by passes in the high mountain range of Taygetos. Indeed, shared cultural features, such as massive chamber tombs, may attest to direct relations between the Eurotas valley of Laconia and the Pamisos valley of Messenia already in Mycenaean times. The Pamisos Valley, the core of what had been the Further Province, would have been most exposed to Spartan aggression in the Early Iron Age simply because of its geographical proximity to Laconia. But the success of the Spartan invasion may also reflect a political weakness attributable to the fact that the area east of the Aigaleon range had not been so well-integrated into the Mycenaean palatial system and thus lacked as strong a sense of common identity as the area to the west. Here the Spartans could and did firmly impose their system.

Messenia after the Bronze Age split along its natural cleavage into eastern and western zones, although some memory of the Mycenaean provinces may be preserved in the Odyssey. Telemachos, son of Odysseus, in search for information about his father, stopped both at the Palace of Nestor and the house of Diocles at Pherai (probably modern Kalamata).44 Only then did he cross from the Pamisos to the Eurotas valley via the Ager Dentheliatis, where the Spartan wars of conquest later began at the Sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis.

Can the prehistoric foundations of Messenia tell us anything about the likely distribution of its Helot and perioikic populations? Common sense suggests that principal Spartan estates would have been located on the best land, in the plains of the Pamisos River and Stenyklaros Plain. Nino Luraghi suggests that patterns of settlement in western Messenia beg to be compared with those in perioikic areas of Laconia, and we agree.45 In the area of Pylos, it seems likely that such perioikic settlements, formed by those who survived the fall of the Palace of Nestor, preserved memories of the Mycenaean past more vividly, while it must have been in the Pamisos Valley that Messenians were “laden with heavy burdens like asses, forced to bring to their lords a half of all the fruit of the soil.”46 Helot resistance against the Spartans was focused on Mount Ithomi in the Pamisos Valley, not the center of the old Mycenaean state, on the western side of the Aigaleon range. It was a popular hero there, Aristomenes, who supported the revolt. No reborn King Nestor led the charge.

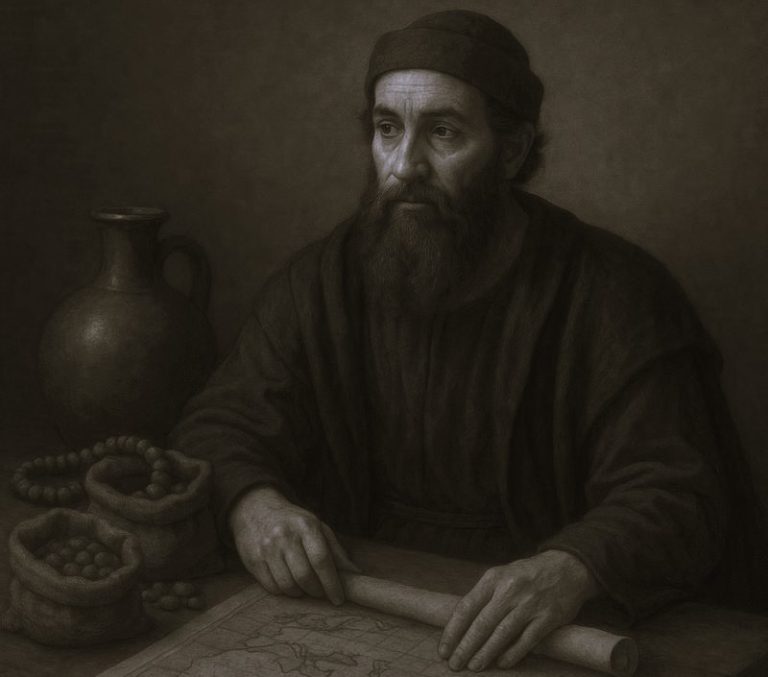

Prehistory also offers grist for the mill of any scholar of Homer. An extraordinary find from Pylos provides one new example. The Pylos Combat Agate, from the grave of the Griffin Warrior, may be the finest example of glyptic art from the Greek Bronze Age ever found (see figure 2). It is a Cretan work of the New Palace period. The face of this seal stone bears a representation of combat that draws on an iconography of battle scenes known from the Shaft Grave period on the Greek mainland and in New Palace Crete. The level of detail in the representation of weapons and clothing, like the attention given to the physiognomy of the human bodies, is without parallel. We realized almost immediately that we had unearthed a masterpiece—one that had the potential to shed light on myth and legend in the Early Mycenaean period.

Schliemann had a strong emotional reaction on discovering at Mycenae the gold signet ring that has become known as the Battle of the Glen and the equally renowned gold ring depicting a hunting scene.47 His interpretation of their iconography in light of Homeric texts was direct:

When I brought to light these wonderful signets, I involuntarily exclaimed: “The author of the Iliad and the Odyssey cannot but have been born and educated amidst a civilization which was able to produce such works as these. Only a poet who had objects of art like these continually before his eyes could compose those divine poems.”48

It is entirely understandable that Schliemann would draw connections between his finds and Homeric tales,inasmuch as he firmly believed that he was excavating the graves of warriors who had fought at Troy. But what were the broader iconographic and mytho-historical contexts of such a scene? Emily Vermeule stated the obvious:

“I need not stress that the great period of Troy VI down to the early fourteenth century is also the great period of Greek interest in battle art and siege scenes.”49

Is it too fanciful to imagine that both mainlanders and Cretans in viewing the Combat Agate would have understood it to be a vignette from a well-known tale? Might some even have recognized one of the city sackers who would become, if they were not already, subjects of the Iliad, our most celebrated saga of war? This is not to say that we must believe that the composition on the Combat Agate was intended by its maker to reflect a Trojan War epic, but as Peter Warren wrote many years ago in reference to the Ship Fresco from Akrotiri and contemporary works,

exploits in such engagements were deemed worthy of record on frescoes, metalwork, stonework and faience. But is not this a familiar story? May we not see these exquisite but silent works as the visual counterparts of oral poets, who have long been thought to have composed their tales of heroic exploits since the earliest Mycenaean times?50

And it is undeniable that elements from the Early Mycenaean period survived frozen in the oldest strata of the Homeric poems.51

The heroic character of the victor depicted on the Combat Agate is emphasized by both his lack of defensive armor and his nearly complete nudity. Such a theme would have been as intelligible to a Mycenaean as to a Minoan viewer, although open to varying interpretations in different contexts, irrespective of the intent of the craftsperson who designed it or any larger composition from which it was excerpted. The victor’s triumph over such a heavily armed opponent expresses his courage, skill, strength, and status. We can imagine that this particular seal held a special significance for the Griffin Warrior and for those who prepared his sepulcher—the depiction of the hero on the seal corresponding to his view of himself and also serving as a reflection of how his family intended to display him to their community in the course of burial ritual. The Pylos Combat Agate clearly befits the interment of one counted among the acquisitive elites who ultimately succeeded in elevating the community on the Englianos Ridge to a dominant position of power in Messenia. He was not Nestor, not Neleus, but an individual no less significant for our understanding of the emergence of the Mycenaean state. Perhaps even the bard depicted on the walls of the Throne Room of the thirteenth-century-B.C. Palace of Nestor continued to sing his exploits.

Endnotes

- Anthropological literature concerning the origins of the state is deep. Fundamental texts include Fried, Evolution of Political Society; Service, Origins of the State and Civilization; Earle, How Chiefs Come to Power; Feinman and Marcus, Archaic States; and Yoffee, Myths of the Archaic State.

- For so-called secondary states, see Parkinson and Galaty, Secondary States in Perspective.

- The foreign schools in Athens, now numbering more than twenty chartered by the Greek Ministry of Culture, are a mix of private and governmental institutions that coordinate and facilitate research in Greece by foreign archaeologists. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Foreign_Archaeological_Institutes_in_Greece.

- Handbooks summarize much of this information, including Cline, Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean; Lemos and Kotsonas, Archaeology of Early Greece; and Shelmerdine, Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age.

- Anne Duray’s Stanford dissertation, “The Idea of Greek (Pre)history,” addresses some of the same questions.

- Cherniss’s scholarship continues today to shape discourse in the field of ancient philosophy, although he is perhaps better known for the role he played in defending Robert Oppenheimer’s standing in the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton and in supporting Berkeley colleagues who refused to sign the loyalty oath demanded by the University of California Board of Regents. Beazley would take up his post later, in 1949, publishing his lectures as The Development of Attic Black-Figure (Sather Classical Lectures 24).

- Blegen was also available to travel, with teaching assignments in Cincinnati only in autumn term; soon he would join the war effort as an OSS officer, recruited to run the Greek Section of the Foreign Nationalities Branch in Washington, D.C.

- For the quote, see Fotiades, “Factual Claims,” 22; see also “Aegean Prehistory without Schliemann.”

- Blegen, “Preclassical Greece: A Survey.”

- Blegen, “Preclassical Greece: A Survey.” By “the Dorian flux,” Blegen was referring to the so-called Return of the Sons of Herakles, known from ancient Greek legends, and once believed responsible for the establishment of the Dorian dialect spoken by the Spartans and others in the Peloponnese in historical times.

- The ASCSA was founded as a private research consortium of American universities in 1887, its mission to educate, conduct excavations, and provide research facilities to students and scholars. Today the ASCSA, located in the heart of Athens, is the largest of the foreign schools of archaeology in Greece.

- Blegen’s Korakou was the first account of an excavation of a prehistoric archaeological site on the Greek mainland to be published by the ASCSA.

- Semple formed the department in 1921, with himself as head, by merging programs in Latin and Greek and adding ancient history and archaeology. He had been smitten by archaeology as a student in Germany, Greece, and Rome and praised it for its ability “to clarify and vivify” Classical literature and philosophy and as a mechanism for promoting Classical studies to a general public by unearthing “new beauty”: “When one digs one is always inspired by the feeling that the next spadeful will turn up something new, something tangible, some beautiful something that without further effort or further ado will immediately and rapturously increase the sum total of the beauty of life.” Quotes are from an unpublished paper titled “Archaeology in General and Troy in Particular,” delivered by Semple on November 19, 1934, to the Literary Club of Cincinnati (Papers of the Literary Club 57 [1934–1935]), 101–5.

- Louis Charles François Petit-Radel (1756–1836) served as director of the Mazarin Library, the oldest public library in France, from 1814 to 1836.

- By employing τις, the ancient Greek indefinite pronoun, Blegen informed readers that his object was the “everyman” of Homeric times, what we might today call “daily life.”

- Leeb, Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, 55. Fallmerayer (1790–1861), a Tyrolean politician, travel writer, and historian, first presented this theory in the foreword to the first volume of his Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea.

- Herzfeld, Ours Once More, 74. Herzfeld explores this conflict in his history of folkloric studies in modern Greece.

- Eleftherios Venizelos (1864–1936), leader of the Liberal Party of Greece, was committed to the incorporation of territories of the Byzantine Empire into the modern Greek state, including Istanbul/Constantinople. On his relationship with Blegen, see Davis, “Politics of Volunteerism.”

- Wace and Blegen, “The Pre-Mycenaean Pottery,” 188.

- For Cyriacus of Ancona and Venetian sources, see Archaeological Atlas of Mycenae; and Moore, Rowlands, and Karadimas, In Search of Agamemnon. For the Italian doctor, see Malliaris, Alessandro Pini, 45 (the translation is mine).

- Review of The Mycenaean Age in The American Journal of Theology 2, no. 3 (July 1898), 646–48.

- No Greek archaeologist had greater influence on the development of the field of Greek prehistory than Christos Tsountas (1857–1934). Tsountas not only excavated at Mycenae and Tiryns but contributed to an understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age through excavations at Dimini and Sesklo in Thessaly, Vapheio in Laconia, and in the Cycladic islands. Voutsaki, “Hellenization of Greek Prehistory.”

- Chadwick, The Decipherment of Linear B; more recently, Fox, The Riddle of the Labyrinth, rightly crediting research by Alice Kober that was fundamental to the decipherment.

- Paparrigopoulos, Ιστορία του ελληνικού έθνους.

- Lalaki, “Social Construction of Hellenism,” for discussion; for the book itself, http://www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/archives/blegens-united-states-and-greece.

- Blegen, “The United States and Greece,” 27.

- Blegen, “The United States and Greece,” 27.

- Blegen to Wace, February 17, 1954, University of Cincinnati Classics Department, Carl W. Blegen Papers, folder 594i.

- Wace, “The Arrival of the Greeks,” 217–18.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, trans. John Skelton (ca. 1487), ed. Frederick M. Salter and H. L. R. Edwards, v. 371.

- Schliemann, Mycenae.

- Tsountas and Manatt, The Mycenaean Age, 340.

- I retain Mycenaean and Mycenaeans to refer to the culture of the southern Greek mainland in the Bronze Age, although others have expressed a preference for the terms Helladic and Helladics.

- Tsountas and Manatt, The Mycenaean Age, 10–11.

- Gardner, “Stephani on the Tombs at Mycenae”; Helbig, “Sur la question mycéni-enne.” Helbig’s theory was quashed by Solomon Reinach in Le mirage oriental.

- Taylour, The Mycenaeans, 15.

- Taylour, The Mycenaeans, 22.

- Gardner, “Annual Report of the Council.”

- Lemos and Kotsonas, Archaeology of Early Greece.

- Cavanagh, “Sparta and Laconia,” 649.

- Pausanias, Book 4.36.1–3.

- Davis and Stocker, “Messenia,” 679.

- Bennet, “Leuktron as a Secondary Capital.”

- Odyssey, Book 3.488–90.

- Luraghi, The Ancient Messenians, 688.

- Tyrtaios, Thesaurus Linguae Graecae fragment 266.5. trans. by the author.

- Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen SiegelI, no. 15 and no. 16.

- Schliemann, Mycenae, 227.

- Vermeule, “Priam’s Castle Blazing,” 88.

- Warren, “The Miniature Fresco from the West House.”

- Sherratt, “Reading the Texts.”

Chapter 1 (1-14) from A Greek State in Formation: The Origins of Civilization in Mycenaean Pylos, by Jack L. Davis (University of California Press, 05.03.2022), republished by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.