It was a coveted territory in antiquity.

By Dr. Maria do Céu Grácio Zambujo Fialho

Professor of Classics

University of Coimbra

Abstract

Basing on the accounts of Thucydides and Plutarch, the paper analyses the way Sicily and the proposed Athenian expedition to Sicily, as a strategic bridge to advance over Carthage, define Nicias and Alcibiades, and what they represent: old Athens, comprised of experienced rulers and devoted, thoughtful citizens, who retreat, aware of the madness and threat of disaster that will lead to the ruinous outcome of the civil war. Forced to join the expedition, Nicias, as the embodiment of this polis, will stay until the end, in a campaign with which he does not agree, trying to save his fellow citizens. Alcibiades together with what he represents are fighting fiercely for the realisation of a megalomaniacal dream that will bring fortune and power for their own advantage. While Nicias accepts the command out of duty and imitation, Alcibiades yearns for it. In this background, Sicily and Carthage, waving from afar with their wealth and promise of power, constitute the stimulus for action that ultimately destroys an Athens close to defeat. On the other hand, in the young Roman republic, Sicily and Carthage offer natural encouragement of the conquest and submission of their power, as an imperative of the logic of expansion, affirmation and survival of Rome as a nascent power. It is the generation of the old Roman nobility that claims Carthago delenda est.

Introduction

Sicily: Its Strategic Position

The historical phenomenon of colonisation,1 as it is known, was a major move-ment. It began with colonising expeditions to islands in the eastern Mediterranean, northeast and southeast and, later, to the coasts of Asia Minor, following a general climate of economic and social crisis that was sweeping mainland Ancient Greece. As a result of Doric invasions, agricultural devastation, and the rough mountainous backbone that runs through the Balkan Peninsula from north to south, leaving only a narrow strip of fertile land between mountain and coast, hungry peasants were fleeing to seek shelter in the cities of eastern Greece—those that had once been founded by Ionic and Aeolian ethnicities, of the same strain to which the refugees belonged. Overcrowding of the poleis, with all its implications, led the most daring of Greeks to regard the sea as a space for recon-structing their lives. Although this movement had seen its expansion from the beginning of the 8th century BCE, reaching its climax in the century 7th century BCE, there exists testimony of the migration of the first Aeolians and Ionians from as early as the end of the second millennium, as well as of the existence of an amphictyony of colonies on the Ionian Sea and the western coast of Anatolia.

The umbilical relationship between a colony and its metropolis would, in future, decisively manifest itself in commercial mobility, in protection in the event of war, but also in the expectation of loyalty and alliance on the part of the metropolis. And that was how this movement was extended, still in the 8th century BCE, to the western and northwestern strip of Greece, as well as to the Peloponnese, populated by Greeks who were, for the most part, of Doric ances-try and whose dialect constituted a different bloc than the eastern bloc, which consisted of dialects that were closer together, such as that of the Ionic-Attic.

The geographical vocation of this new colonisation movement was, naturally, to look to the west and, through the Ionian Sea, reach Sicily, the western coast of the Italic Peninsula and the Mediterranean coastal strip of the current French Riviera, up to the Iberian Peninsula. The importance and prestige of the entire complex of colonies founded there justifies the designation by which this entire region would later be known: ἡ Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς (Polybius 2.39.1; Strabo 6.1.2). Within this cosmos, Sicily stands out. Due to its climate, the richness of its soil and subsoil, and its geostrategic position, as guardian of the passage between the eastern and western Mediterranean, this island attracted the attention of those leading the colonising expeditions, who would come to found cities that saw a rapid development and soon became rich and powerful. This was the case, among others, for Syracuse (733), Selinus (650–628), Himera (649), Gela and Leontini (also in the 7th century). Later, we witnessed the phenomena of the foundation of new cities by citizens of established colonies: this was the case for Agrigentum (581–580), founded by citizens of Gela, and for Camarina, founded by Syracusans. The island’s own extension and geographical configuration established a network of relations between its cities, giving rise to new centres, but also to a complex web of hostilities: let us recall, for example, the town of Leontini, occupied by Gela and subsequently maintained under the control of Syracuse, or the story of Camarina, created by Syracusans in 599 and destroyed, again by Syracusans, in 552. Gela supported its reconstruction in 461 and, in 405, the city once again fell victim to the conquering threat of Carthage.

The island’s wealth and strategic position had long since shaped it as a coveted territory in Antiquity. The indigenous population coexisted with Phoenicians, who had introduced commercial warehouses and converted them into prosperous cities, such as the city of Egesta, whose origins are lost in time. Thucydides 6.2 attributes its foundation to Trojans fleeing the devastation of their homeland. The city was not Greek and, if we believe the testimony of Diodorus Siculus 11.20.71, there were rumours of hostilities between Egesta and Selinus from 580 BCE onwards, as the territories of both cities expanded—clashes that would continue between them.

Indeed, the Sicily colonised by the Greeks was not a formerly uninhabited territory. In addition to indigenous ethnic groups, the Phoenicians had established themselves there and, moreover, the Carthaginians then controlled part of the island, especially to the west and northwest (Hitchner 2009, 430–1). Eager to take advantage of the rivalry between the cities, the Carthaginians, commanded by Hamilcar I, responded to the call of the tyrant of Himera, who was expelled from his city by Theron of Agrigentum. This aimed to weaken the growing hegemony of the new inhabitants, which posed a threat to their dominance of the Western Mediterranean and their strategic position between West and East, capable of converting Sicily into a vast strategic bastion.

Despite an extensive fleet, advances on the island were hampered by a storm. Still, Hamilcar’s forces advanced to Himera, where they were confronted with a Greek coalition, led by Gelon of Syracuse. The defeat of the Carthaginians, in 480 BCE, is symbolic of his loss of power and influence in Sicily, lasting for many years.2 Syracuse, for its part, grew in power and preponderance over the other poleis and fuelled its hostility towards Carthage. An awareness of the strategic position and wealth of the largest island in the Mediterranean determined the multiple pretensions of dominion that stretched over it for centuries.

Sicily is praised for its livestock and fertility. Numerous allusions attest to this throughout Greek poetry: Pindar, in his Olympic Ode I, dedicates his lyrics to the tyrant of Syracuse; Hieron, who is victorious in the horse races at the Pan-Hellenic games, is based “in Sicily rich in cattle” (ἐν πολυμήλωι Σικελίαι, v v.12–3); in the victory song in honour of Hieron of Etna, the poet praises the polis, famous for its festivals and for its horses (P. 1.37–8), near the fearsome mountain, “front of the fruitful land” (εὐκάρποιο γαίας μέτωπον, P. 1.31 ); “The vast fields of fertile Sicily” (τῆς καλικάρπου Σικελίας λευροὺς γ ύας) are invoked by Aeschylus, the Sicilian poet, in the words of Prometheus (Pr. 3 6 9).3

And that land, which would become the breadbasket of Rome, allows the Syracuse tyrant, Gelon, to respond to the Hellenic symmachia embassy that travels to his city in 480 and asks him for support and alliance against the Persians, with the promise of generous military reinforcements of men, horses, and ships, as well as general provisions for Greek livelihood, as long as the great confrontation with the Persians endures—this, in exchange for granting him command of the army. The Spartan envoy violently refuses, according to the account of Herodotus 7. 158–61. Gelon makes a new proposal: the offer of outstanding support if, at least, he is given leadership of the Greek fleet, which the Athenians refuse. Gelon then retreats to a position of neutrality (Hammond 1986, 223–5). It should, in passing, be said that, among the reforms implemented by the tyrant in the government of Syracuse, one of the most notable was the organisation of a proper naval force that would ensure the undisputed hegemony of his city on the island, as a naval power capable of facing the Carthaginian enemy.

Sicily: A Source of Knowledge and High Achievements

That episode, reported by Herodotus, mirrors the conscience and proud affirmation of a Sicilian identity before the Hellenic symmachia, whose representative approaches the lord of the most powerful polis of this great island. From this it can be concluded that, in terms of its resources, Sicily is autonomous, and that its great weakness lies in its motherland: the rivalries between its poleis. Gelon, through his alliance with Theron of Agrigentum, which is consolidated when he marries his daughter, Demarete, is capable of seizing power in Syracuse, which he governs between 485–78 BCE. He destroys and annexes several Sicilian colonies and transforms Syracuse—that colony founded by Greeks from Corinth, the eternal rival of Athens—into the most powerful city of the island. Meanwhile, shielded by his symmachia with Agrigentum, he resumes hostilities towards the Carthaginians. It is in this context that the Battle of Himera takes place.

Gelon inaugurates the tradition of participation of the Sicilian aristocracy, namely of the city governors, in the Panhellenic games. In 488 BCE, he wins the horse chariots race at the Olympic Games and thus inaugurates a brilliant tradition that finds echoes in the epinikia of Pindar and Bacchylides, dedicated, for the most part, to the winners of several modalities using horses, who are in charge of numerous poleis of the island (Hirata 2012, 23–38): Syracuse, Agrigentum, Etna, Himera, Gela. It is understood that this is a policy of Panhellenic affirmation of the authority and prestige of these great lords, who hold absolute pow-er. Euripides, in his Trojan Women, v v. 222–23, bows to this splendour of glory from successive sporting victories, when he praises the land of Etna through the Chorus of Trojan Captives and its crowns, which were obtained in the games and expanded its fame by merit.

In fact, a phenomenon peculiar to many of the colonies, including those in the Aegean, lies in the form of government adopted. The colonies of Sicily are, even in the classical era, ruled by tyrannoi, descendants of the founders of the cities, several of them associated, by kinship ties or wedding rings, with the reigning house of Syracuse, as seen above, for example, between Syracuse and Agrigentum (R hodes 2007, 71–3). It was only as they approached the second half of the century V BCE that the political landscape began to change and, one after another, the Sicilian poleis grew familiar with a democratic regime. This movement started with the revolt and expulsion from Syracuse of the tyrant Thrasybulus, in 466, and the subsequent institution of a democratic form of government, before then extending to other cities (Rhodes 2007, 76).

The form of deliberation in the assemblies and voting in judicial cases promotes an awareness that, in addition to the weight of truth inherent in the argument, powers of persuasion depend heavily on the expertise behind the argument. Thus, persuasion becomes autonomous as an art form, capable of being learned, with precise techniques. The Syracusans Corax and Teisias were the first two figures of whom there is an echo in this early rhetorike techne. The last quarter of the fifth century is notable for the presence of Gorgias of Leontini, the Sophist and Rhetor, in Athens, who taught the art of the word in exchange for money,4 demonstrating the possibility that a discourse built on expertise can persuade listeners either of a thesis or of its opposite.5 The teaching of the Sophists in Athens, and their discussions in the agora, which coincide, precisely, with the troubled time of the Peloponnesian War, provoked a sharp revolution of mentalities and a strong sense of controversy between those who rejected them and their disciples or sympathisers (Guthrie 1971, chap. 8).

In Magna Graecia, between the 6th and 5th centuries, and between cities in the south of the Italian Peninsula and Sicily, a great circuit of ideas and philosophical schools was constituted, within the scope of Pythagoreanism and its contamination with Orphism (Bernabé 2013, 121–30; Casadesús Bordoy 2013, 153 ff.), the dimensions of which cannot be determined, neither by the Ancients, nor by contemporary research (Rossetti and Santaniello 2004, chap. 3). Plato visited Archytas’ school in Tarentum several times; by contrast, without having travelled to Athens, Empedocles of Agrigentum saw his philosophy spread throughout the Greek world, including Athens. This involved his cosmogony and theory of the four elements and the dynamic role of Neikos and Philia, as well as his views with respect to ontology and his convictions about metempsychosis (which coincide, to a great extent, with the reports that Herodotus 2 would have heard in Egypt).

Thus, for the collective of Athenian citizens facing troubled times of civil war in the last quarter of the 5th century, the distant Sicily imposed itself, on the imagination and knowledge of travellers, as a safeguard between the western and eastern Mediterranean, a buffer against Carthage expansionist ambitions and a land of fertility and prosperity, wealth and glory, strength and wisdom, albeit suffering from a terrible evil: that of a devastating hostility between cities, based on alliances or intentional strategy. Hence the formation of the verb σικελίζω, “to be in bad faith, like the Sicilians”, occurring in Epicharmus.

Athens and the Expedition to Sicily (415-13 BCE) in the Context of the Peloponnesian War

Background Hostilities (427, 424, 422 BCE)

From the middle of the 5th century, following the democratisation of the Sicilian poleis, Athens began, with increasing interest, to follow developments in Magna Graecia. Syracuse, in its eagerness for hegemony in Sicily, tried to dominate the political constellation of the island, continuing its attacks on other cities—an action that was far from eased by the context of the Peloponnesian War. Fully aware of the original animosity between Syracuse and Athens, cities allied to Athens, such as Leontini and R hegium (in current Calabria), sought the assistance of the latter in the unequal war they waged with Syracuse, supported by the island of Dorian poleis (with the exception of Camarina and the Chalcid-ian cities, Thuc. 3.86). An embassy was sent to Athens; one of its members was the speaker Gorgias, whose art of persuasion would have deeply impressed the Athenians (Plato, Hp. Mai. 282b). In 427 the Athenians then sent a fleet of 20 ships to Sicily, under the command of two generals. This would ensure control of the strait between Italy and the island, with the Athenians installed in Rhegium. According to Thucydides 3.86:

The Athenians sent it [a fleet] upon the plea of their common descent, but in reality to prevent the exportation of Sicilian corn to the Peloponnesus and to test the possibility of bringing Sicily into subjection. Accordingly, they established themselves in Rhegium in Italy, and from thence carried on the war in concert with their allies.6

On beginning the account of events in which Alcibiades was involved and which led to the ruinous expedition to Sicily, Plutarch, Alc. 17.1 recognises that “already in the life of Pericles, the Athenians had their eyes set on Sicily”.7 After his death they joined the campaign. Every time a Sicilian community was mistreated by Syracusans, they sent what they called “aid” and “military support”. And the island became the primary target of the young Alcibiades (Alc. 17.2).

It is quite probable that, in view of his ambition to command an expedition to Sicily, Alcibiades would have been concerned to impose himself, in the eyes of the Assembly and the demos, as an energetic, implacable and triumphant general. His eccentricities, allied to his prodigalities, exercised a manipulative power of the demos, which excused those (Plut. Alc.16).8 He seems to have been one of the fiercest defenders of the attack and the fate given to the Melians, in the expedition and siege of 416 BCE (see Rhodes 2011, 37–8)—this same man who takes a Melian captive as his concubine, to whom he makes a son.9 Another of his bets consisted of ostentation and triumphs in the Olympic Games (although the way in which he appropriated chariots bought by Teisias was the subject of yet another of his scandals).10

This call from both Sicilian factions for support from parties at war led Sparta to set expectations for support from Syracusans—but to no avail. Skilfully, Hermocrates of Syracuse proposed a peace treaty between the remaining Greek cities on the island, in order to be freed from the influence and pressure of Athens and to maintain the island’s autonomy. The deal was made in 424. The Athenian forces stationed there returned, defrauded, to their homeland, without having achieved Sicilian dominance. Instead of taking control of the island, their generals were removed or accused of receiving bribes (Hammond 1986, 369–70; Rhodes 2 0 0 7, 10 2 – 6).

This coalition, however, was extremely fragile, not only because of the military record between the cities, but also because living conditions were changing rapidly. The war aggravated disparities between rich and poor, which fostered conditions for civil strife. In Leontini, democrats proposed land redistribution, which the oligarchs rejected. The same happened in Messina, resulting in civil war between social classes, just as in Leontini and Corcyra. The Leontini oligarchs sought Syracuse’s assistance. This was, according to Athens, an opportunity to try to reach an agreement against Syracuse. In 422 the Athenians sent Phaeax, leading a diplomatic embassy, to the ancient allied cities of Sicily, in the hope of being able to recover an alliance against Syracuse. Times had changed: Phaeax was well received in Agrigentum and Camarina, as well as by the Siculi and Locrians, but the same could not be said in Gela and other cities (Thuc. 5.5–6). Disappointed, Phaeax returned to Athens, when the Peace of Nicias was brought about following the death of Cleon at Amphipolis, in a battle against the Spartans, who were commanded by Brasidas. Once again, a prosperous Sicily thus evaded Athenian attacks, in search of allies and, above all, the geostrategic domain that the island represented.

Divergences in Athens: Around the Sicilian Expedition (415-13 BCE)

Nicias and Alcibiades: Two Groups in Opposition

After long and difficult talks and negotiations, Sparta and Athens managed to sign a peace treaty in 421 BCE that should have been in force for fifty years. It is evident that, after Cleon’s death and substantial losses in the war, both Sparta and Athens were eager to regain peace. General Nicias, renowned for his performance in the war and his prudence,11 was presented with this difficult dialogue with the enemy.12 The peace achieved by Nicias was received with enthusiasm in Athens. The agricultural Athenians saw in that peace the return of times when they could safely cultivate their farms (Hammond 1986, 380). The old aristocracy, for its part, considered that conditions ripe for the normal functioning of the city and its institutions had been restored. However, the expectations brought about by the war had not been fulfilled at all: hostilities persisted with Boeotia, Megara, Corinth. The Athenians’ conquest of Sicyon in the summer of 421—resulting in the cruel execution of all men and the exploitation of women and children as slaves (Thuc. 5.32)—increased the animosity between cities in the Peloponnesian League. The Chalcidians attacked cities allied with the Athenians and captured a garrison. Despite the truce, Athens’ citizens were therefore prisoners of war.

In addition, it should be recalled that there was a dangerous distance and conflict of interest in Athens between descendants of the old aristocracy and the agitated demos that filled the assemblies. Hammond (1986, 369–70) points to the consequences of the plague: it had stolen the lives of a third of the population. In the year of 424, despite recent military successes, the city therefore had a reduced military force—the number of hoplites was low. The fleet, for its part, was reinforced: the plague had clearly not hit the ships and the crew was essentially made up of people recruited from the lower classes: artisans from whom the war had stripped their usual work, or landless rural workers—the thetai, paid as mercenaries, for whom war was a source of income. Small farmers, in turn, experienced the tragedy of systematically devastated fields, while the Athenians of wealthier families, through trade, land tenure, and mines, paid taxes to the state coffers and maintained, through their land, a relationship of deeper roots, which increased their desire for peace and stability. It was, in turn, these people who were responsible for leading the military forces into battle, by land or sea. Invigorated by warmongers, they avoided confrontation with the crowds in Athens. This ochlophobia was not, therefore, a unique feature of Nicias, but rather a typical reaction of a social group.

Lasting peace was unlikely from the outset: the interests of the poleis of both constellations were abundant and diverse. There were even cities in the Peloponnese and, above all, Corinth, that were unhappy with the conditions of the treaty. They too yearned to satisfy and guarantee their acquired hegemonic interests. Corinth went so far as to create an autonomous league with Boeotians, Thracians and Megarians (Thuc. 5. 38), with a view to also involving Argos. By the winter of 421–20 the climate had changed, even in Sparta: two new ephors, Cleobulus and Xenares, defended the reinstating of hostilities (Thuc. 5. 36). As conditions deteriorated, according to Thucydides 5.45 (followed by Plutarch, Alc. 14–5), the young Alcibiades entered the field in the summer of 420 BCE, in order to put into practice a subtle and perfidious plan of intrigue, provoking the wrath of the Assembly of Athens against Spartan ambassadors and causing the Athenians, on impulse, to establish an agreement with Argos, the traditional antagonist of Sparta (Ruzé 2006, 269–72; Rhodes 2007, 126), as well as with Mantinea and Elis (Romilly 1995, 64–7).

According to Thucydides 5.46, Nicias attempted to lead the Assembly to postpone the agreement with Argos. Their efforts were in vain and did not prevent the truce from being officially broken. It was then that Alcibiades started to gain supporters in the Assembly, having been immediately elected commander. At the same time, he continued its efforts to discredit Nicias.13 As a matter of fact, Nicias represented the voice of the citizens who disagreed with a euphoric and dangerous military policy, while his prudence, taste for privacy and aversion to crowds were well known. Alcibiades, on the contrary, yearned to be the centre of attention. As vain as he was intelligent, as prone to excesses and eccentricities as he was capable of seducing public opinion, ambitious, manipulative and endowed with a refined oratory talent, Alcibiades knew how to play on the volubility and emotions of the masses.14

Plutarch (Alc. 17.1–2) recognises that the Athenians had their eyes set on Sicily, even at an early stage of Pericles’ life. Pericles, however, knew how to curb the crowd’s foolish impulses. As recognised by the polygraph of Chaeronea, conquering the island was a clear objective of the young Alcibiades, who was thus preparing, from an early age, to boost morale and mobilise the Athenians for a campaign from which he hoped to extract maximum glory and profit.

Nicias did not belong to the generation of Alcibiades. He was a prestigious general, having proved his worth in the field in the year of 424. In a joint action with Demosthenes and Hippocrates, he had achieved success through a strategy of blockading Sparta, by means of the conquest and occupation of strategic cities in favour of a great rival, intercepting commercial maritime circuits (Hammond 1986, 368–421). He belonged to the same generation as Cleon. However, a deep contrast separated them in the way they conducted themselves in political life. Concerning Cleon, Thucydides suggests that he was the first to deserve the designation of demagogue;15 aggressive and relentless in attacking antagonists in the Assembly, he argued in order to obtain the favour of the people. Nicias, on the other hand, remained discreet and avoided the crowds, whose emotional irrationality he feared, despite his performance in the war and the generous way in which he distributed his personal wealth.

Nicias did not have an aristocratic ancestry, but he behaved like an aristocrat and identified himself with the aristoi, from whom he sought and obtained sympathy. As Plutarch informs us, the enormous fortune inherited from his father was due to the possession and exploitation of silver mines in Attica (Plut. Nic. 4.2). He was a pious man and possessed a noble character, although, in the synthesis formulated by Rhodes (2007, 121), and in keeping with Plutarch’s Vita, “he may have been general every year from 427/6 until his death in Sicily in 413: he seems to have been a competent commander, but more anxious to avoid failure than eager to achieve success”. This is undoubtedly an aspect explored in Alcibiades’ argument in the Assembly where the great expedition was decided on.

The speeches made by Thucydides, in his book 6, and attributed to Nicias and Alcibiades, do not correspond to exactly what was pronounced by the two antagonists. However, their verisimilitude and potential truth are valuable—they correspond to what would have potentially been said according to the circumstances, characters and position of the age group and the respective ethical and political values that each of the two speakers represented. On the one hand, the reader apprehends, in this way, the ethos of both figures, their intentions and motivations, the political and social context in which they speak and what they defend. Nicias represents the voice of thoughtfulness, embodying the prolonged experience of leading the war, of those who defend, above all, the security of Athens and the stability of the city, to arrive, unscathed, at a time of peace: from a group that is increasingly stifled by the noise of the demos, stimulated against the madness of the demagogues, the group of an aristocratic generation, wounded by the war and its visceral relation to the city.

On the other hand, although descended from an aristocratic lineage, Alcibiades represents, to the worst extreme, the voice of a new aristocracy—that of dissolute, ambitious young people, thirsty for adventure and protagonism. He prevailed over these young people, according to the multitude of testimonies from Thucydides, Xenophon, Plato, Plutarch. It is a generation that is the product of war and that, in the extent of its ambition, approaches the irrational greed of a crowd, influenced and manipulated by the argument of profit and wealth induced by war. Alcibiades dominates the powerful new weapon brought precisely from Sicily, by Gorgias, to the Athens of his time: the technique of argumentation and persuasion. He prevails over Nicias.

The arguments exchanged may not have been between the two, but they certainly correspond to the incongruity of opinion in Athens: one formulated more timidly, the other in a sonorous and ostentatious way. Prudence and experience lead us to consider that, at the point the war has reached, it is extremely dangerous to breach a military front (Thuc. 6.10), sending part of the forces to Sicily. This strategy weakens Athens and endangers the control of the empire it still has in the East. In addition to this argument, another emerges, based on experience of relations with Sicily: the island, despite its strategic interest, is too far away, in the event of an Athenian victory, to possibly be controlled remotely (Thuc. 6.11). There is an awareness that, if the island’s cities are rich, they are also powerful and of stable government (Thuc. 6.20). They would understand each other more easily than they would tolerate Athenian hegemony. This argument was based on historical background.

The greed and euphoria of power are fixed on the wealth and prosperity of the island and its cities, belittling their strength. The mistakes pointed out by Thucydides (2.65.11), concerning the initiative of the expedition, may be the geographical ignorance of the demos, led to approve it, but the generals knew perfectly what kind of physical obstacles were between Athens and Sicily (Mosconi 2021, 186–94).

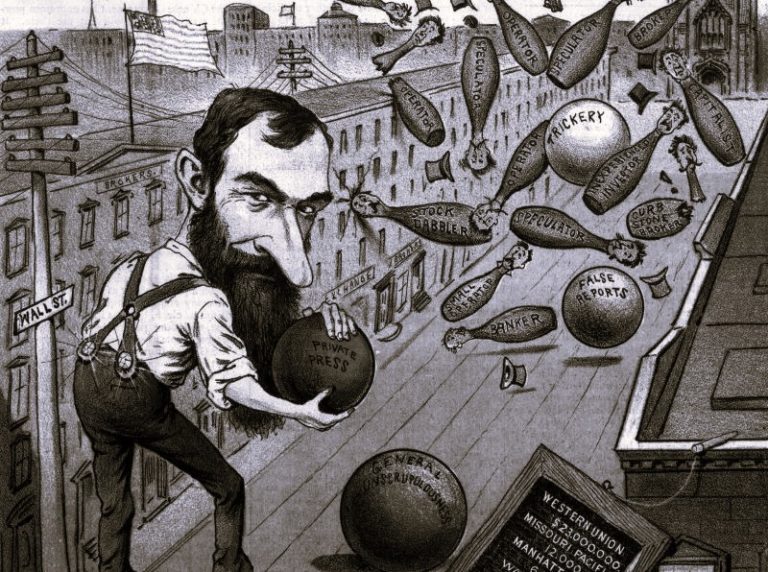

Based on the constant wars between the cities of Sicily, it would be easy—but mistaken—to conclude that their governments are weak and chaotic (Thuc. 6.17) and, therefore, that the campaign would be easy and guaranteed to bring a certain profit and glory. And as if distance were not enough, Alcibiades (or the strand he represents) argues with a strategic leap that, given the distance, represents a mirage: Sicily is a bridge to Carthage and to an assault on the wealth of another empire (Thuc. 6.15.2). Thucydides understands and points out to Alcibiades’ immensely ambitious plan: to conquer Sicily in order to pass to Carthage.

What represents a mirage of ambition, due to this distance and military con-text, will reveal itself, for another state in the process of affirmation and expansion, as a natural and inevitable undertaking: for the Rome of the early days of its republic. Sicily represented, as it were, the natural extension of Italy and the outpost in the Mediterranean. In Sicily, the need to neutralise another empire by having a presence there—Carthage, based on the African coast and dominating the sea—would certainly be confirmed. For the safety of Rome and its navigation, so that the Mediterranean could become the mare nostrum, evidence is imposed, this time by irony of fate, on the conservative optimates of old Rome: “Carthago delenda est”. Shy was the voice of those who eventually advocated the opposite thesis.

Thus, in the face of Egesta’s request for help, promising deceptive treasures if the Athenians assisted it in the war against Selinus, a city then supported by Syracuse, the Assembly voted in favour of sending the disastrous expedition.16 For fear that Alcibiades would take absolute power in the campaign and, later, in Athens, Lamachus and Nicias were, in addition to Alcibiades, appointed as chiefs.

It is around this time, in the summer of 415 BCE, that numerous Hermes were found at dawn, beheaded in the streets of Athens. Suspicion fell on Alcibiades and his ensemble of night parties. Witnesses were listed. Soon after, there was a rumour that Alcibiades and his friends had, in one of their parties, staged a parody of the Eleusinian Mysteries (Thuc. 6.27). It remains unclear whether Alcibiades was the author or instigator, or whether the two sacrileges were designed to incriminate Alcibiades, for civic fear that the young man presented the threat of becoming a tyrant; what is certain is that a lawsuit was filed against him.17

So, when sailing on the high seas, the fleet sees the ship Salaminia, which had come seeking Alcibiades to be tried. The young general then escaped to Sparta. Lamachus later died in Sicily and it was Nicias who continued a campaign with which he was at odds, already sick and injured, until he was cruelly killed in 413 at the hands of his enemies, pleading nobly for the life of his soldiers, according to Plutarch (Nic. 27.5), to the Spartan general Gylippus in Syracuse. Thucydides 7.83.2–4 gives us another version: realising that the Greeks are irretrievably lost, Nicias proposes to offer a very high sum of money from his personal assets, if the Sicilians and Gylippus allow the Athenians to return safely to their motherland. The offer is declined. In 7.86.2–3, Thucydides cites that generals Nicias and Demosthenes were savagely murdered by the Sicilians, against Gylippus’ will, adding that Nicias had not deserved that fate.18

This effect of tragic outcome is literarily prepared through its contrast with the final speeches given by the Athenian general, in which his ethos of a pious man towards the gods, and a just citizen towards men, with a deep sense of belonging to his polis, leads him to urge and appeal to his soldiers’ sense of political community. This speaking voice is that of an Athens from the past. The Athens of the present, having already lost its most devoted leaders and citizens, is delivered into the hands of an uncontrolled crowd comprised of those who manipulate in accordance with their interests.

Alcibiades, having gone to the Spartan side and later taken refuge in the court of Persian satraps, eventually returned to Athens, where he would liberate the way to Eleusis and obtain brilliant but brief victories. He ended up as a fugitive, pursued by the weight of his own vices, while Athens faced defeat in a ruinous war. The organisation of the polis would never recover.

Concluding Remarks

The Time of ‘Great Men’: Stasis or Disruption?

Aristotle repeatedly stated, in his Nicomachean Ethics and in his Poetics, that the human ethos is defined in action and that human action develops, on the part of each agent, with one objective—to achieve eudaimonia. In truth, this eudaimonia is measured and gains meaning in the context of the polis. Applied as a reading tool, this perspective on the paths of Nicias and Alcibiades seems extremely productive—so much so that Plutarch appears to have resorted to it too.

In times of upheaval and civic disorder, class unrest, parties, threats from within or without, which disintegrate a community, its future destiny—whether that be a new order or destruction and wandering—remains in doubt. It is in these fracturing historical moments that figures who usually identify with one of the groups in dispute appear, or who see, beyond the dispute, the sensible solution to reach. They may take the profile of natural leaders, who impose themselves through their leadership skills and with whom a community identifies, or they can become “leaders by force”. In this case, these are figures respected for their status and qualities of character, but without political ambitions—lovers of their private life, who are compelled to assume a leadership role by conjuncture and collective request. Let us recall, for example, the figure of Cincinnatus in Rome.

In any case, these figures, who we can call “great men”, give voice to a collective conscience. In times of crisis and rupture, communities lack visible representations of their identity markers as a promise of stability or confidence in the revolutionary adventure. The historian, on the other hand—and this is already noticeable in Thucydides—tends to project onto such figures the reading he makes of an era, of a crisis, of the consciousness of a people or a class. Historical biography and literary portraits are grown from this dynamic. Plutarch’s Vitae constitute an exquisite example of this construction of a character-symbol, as a field for the projection and personification of a historical process of which he becomes an agent, of the collective spirit that gives him a dimension of universality (Catroga 2004, 257–60).

Can we understand as stasis, according to the Aristotelian concept (Pol.1.2.1253a),19 this whole process of conflict and confrontation in the polis? In the beginning, in the historiography of Thucydides and the biography of Plutarch, both Nicias and Alcibiades concentrate in themselves the representative dimension of two groups that, in Athens, have been confronted, moved by opposing interests, guided by antagonistic values. However, as can be seen, while Nicias sets up the struggle for what is fair and useful to the city, acting prudently, even reluctantly, but within a traditional model of piety, Alcibiades sets up the dimension of individualism of all those who encourage war for their own benefit. This faction dominates the events and change to which the city is subjected and which the polis will soon undergo. It does not represent the establishment of a new order, but rather the extreme disruption and weakening of democracy and of the polis system itself, without a valid alternative.

Thus, the course of action and life of Nicias, in the History of the Peloponnesian War and in the Parallel Lives of Plutarch, tends to embody the journey and destiny of an old caste of citizens of Athens, characterised by their nobility, piety, love of the city and compassion—a caste of citizens, guided by democratic ideals, who were by no means at ease in the face of agitated assemblies or crowds manipulated by demagogues. This Athens was shipwrecked by the disaster that was the expedition to Sicily, without deserving such a destination. In turn, refined in intelligence and perversion, Alcibiades is the symbol of a new Athenian caste, eager for profit and fame, grown in and having assimilated the logic of the war: everything is worth, intrigue, command by arms, dominion of crowds by the art of argumentation, to achieve their ends. The city is only the means by which personal interests are achieved.

Greece and Rome: Their Views Towards Sicily

Thus, Sicily and the proposed expedition to Sicily, as a strategic bridge to advance over Carthage, define both figures and what they represent: old Athens, comprised of experienced rulers and devoted, thoughtful citizens, who retreat, aware of the madness and threat of disaster that will lead to the ruinous out-come of the civil war. The threat that constitutes the people in a manipulated uproar in the Assembly intimidates and inhibits the arguments of this Athens. Forced to join the expedition, Nicias, as the embodiment of this polis, will stay until the end, in a campaign with which he does not agree, trying to save his fellow citizens. Alcibiades and what he represents are fighting fiercely for the realisation of a megalomaniacal dream that will bring fortune and power for their own advantage. W hile Nicias accepts the command out of duty and imitation, Alcibiades yearns for it. However, on the verge of being taken to court before the city, he dodges and passes to the enemy’s side. He will survive, thanks to his unparalleled chameleonic capacity,20 with Spartans, Persians; he will return to Athens, in triumph, and end up being persecuted, ingloriously killed, victim of his own vices. Alcibiades is the image of this new suicidal Athens.

In fact, Plutarch carefully chooses the public figures of the Greek and Roman universe to be biographed according to their potential to represent a personification of the qualities and defects or the essential of the historical trajectory of the community to which they belong—Alcibiades’ Vita, which follows so closely the historical narrative of Thucydides, is not an exception.

Sicily and Carthage, waving from afar with their wealth and promise of power, constitute the stimulus for action that ultimately destroys an Athens close to defeat.21

On the other hand, in the young Roman republic, Sicily and Carthage offer natural encouragement of the conquest and submission of their power, as an imperative of the logic of expansion, affirmation and survival of Rome as a nascent power. It is the generation of the old Roman nobility that claims Carthago delenda est.

Appendix

Endnotes

- This research was developed for the project “Rome our Home: (Auto)biographical Tradition and the Shaping of Identity(ies)” (PTDC/LLT-OUT/28431/2017), funded by the FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology. This research is also part of the project “Crises (sta-seis) and changes (metabolai). The Athenian democracy in contemporary times” supported by CAPES (Brazil) and FCT (Portugal) (2019–2022).

- Herodotus 7.166–67 asserts that the battle took place on the same day as that of Salamis. Although this was not the case, this reading reveals the awareness of the analogous and decisive consequences of the two battles for the survival and reinforcement of Greek identity. See the account of Diodorus Siculus 11.20–7.

- It is not appropriate to engage here in discussion about the authorship of the play, as it deviates from the objective of this study.

- Cf. Euripides, Hec., v v. 812 ff.

- López Eire (2002, 191–6) underlines the psychagogical dimension as an objective of Gorgias’ rhetorical-argumentative technique. This is evidenced by the fact that Gorgias composed a speech “Against Helen”, which was lost, and another “In defense of Helen”, which reached us partially.

- As pointed out by Rhodes (2007, 103–4): “We do not know to what extent the Peloponnesians were importing grain from Sicily, but if they did they could spare more time from their own farms for fighting. Whether the Athenians were already thinking of conquest Sicily in 427 cannot be confirmed, but they were certainly doing so by the end of this campaign in 424”.

- Translation borrowed from Strassler and Hanson (1996). On the whole relational complex of Magna Graecia with continental Hellas, according to the perspective of Thucydides, see Zahrnt (2006).

- Bearing in mind that these are attitudes and strategies adopted by an aristocrat with the aim of manipulating public opinion about him, Mosconi’s systematization and conclusion, in the last thesis (2021) is right: the demos has deliberative powers and competence, but it is ultimately vitiated, by political leaders who were given command responsibility.

- According to Vickers (1999a, 265–281), the ‘Dialogue of the Melians’ represents a careful approach, on the part of Thucydides, to make understandable Alcibiades’ connection to this undertaking. Cf. Vickers 2019b, 115 ff.

- Stuttard 2018, 134 ff.

- Although Plutarch (Nic. 6.1–2) interprets the reticence of Nicias in action as a defect, reflecting indecision and lack of commitment to developing warlike actions, it is important to remember that Plutarch sets up his presentation of Nicias according to the parallelism established with Crassus, in the Vitae of both, preparing a final evaluative judgment in favour of Crassus.

- Rhodes (2007, 124): “But a peace which resulted from Sparta’s failure rather than Athens’ success might in any case not have been long-lasting; and, as we have seen…, the terms of the peace were not fully implemented and several of Sparta allies refused to swear it.”

- Cf. Plut. Alc. 14.4 –5.

- On this point, Plutarch agrees with Thucydides and observes the Athenian historian very closely.

- Thuc. 4. 21. Vide Rhodes (1997, 120), who notes that, even so, Thucydides seems to have exaggerated Cleon’s character traits.

- On the deceitful behaviour of Egesta see Rhodes (2006, 537–38).

- On Alcibiades and the Eleusinian Mysteries, see Leão (2012), with bibliography.

- Rhodes (2007, 140) remarks: “The hard-headed Thucydides has puzzled his readers by making no comment on Demosthenes but remarking that Nicias was particularly undeserving of his fate because of his devotion to virtue”.

- On the “politicization” of stasis in Aristotle see Rogan (2018, 207–10).

- This topic was previously addressed by Fialho (2008, 107–16).

- Soares, in his contribution to this volume, published as the chapter “Nature and natural phenomena in Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War: physis and kinesis as factors of political disturbance” considers: “After having imposed the law of physis upon nomos against the Melians (V.84–116), it is the Athenians who will experience the unstoppable law of physis in their disastrous expedition to Sicily” with Nicias and Diodotus representing peace and Cleon and Alcibiades embodying war. So, the author concludes: “Stasis alone configures an extreme image of kinesis, an eruption of terrible social and political consequences”: this is the huge stasis that fatally shook the foundations of Athenian democracy.

Bibliography

- Bernabé, Alberto. 2013. “Orphics and Pythagoreans: the Greek perspective.” In On Pythagoreanism, edited by Gabriele Cornelli, Richard Mckirahan, and Constantinos Macris, 117–52. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110318500.117

- Casadesús, Bordoy F. 2013. “On the origin of the Orphic-Pythagorean motive of the immortality of the soul.” In On Pythagoreanism, edited by Gabriele Cornelli, Richard Mckirahan, and Constantinos Macris, 153–76. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110318500.153

- Catroga, Fernando. 2004. “O magistério da História e exemplaridade do ‘grande homem’: a biografia em Oliveira Martins.” In O retrato literário e a biografia como estratégias de teorização política, edited by José R . Ferreira, Maria do Céu Fialho, and Aurelio Pérez Jiménez, 243–87. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade.

- Fialho, Maria do Céu. 2008. “From flower to chameleon. Values and counter-values in Alcibibiades’ Life.” In Philosophy in Society. Virtues and Values in Plutarch, edited by José R . Ferreira, Luc Van der Stockt, and Maria do Céu Fialho, 107–16. Leuven and Coimbra: University Press.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. 1998. The Sophists, 3rd repr. ed. Cambridge: University Press.

- Hammond, N. G. L. 1986. A History of Greece to 322 BCE, 3rd repr. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Hirata, Elaine F. V. 2012. “Monumentalidade e representações do poder tirânico.” In Representações da cidade antiga. Categorias históricas e discursos filosóficos, edited by Gabriele Cornelli, 23–38. Coimbra-São Paulo: Imprensa da Universidade-Annablume. http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/9 78-989-8281-20-3_ 2

- Hitchner, R . Bruce. 2009. “The Mediterranean and the history of Antiquity.” In A Companion to Ancient History, edited by Andrew Erskine, 429–35. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444308372.ch37

- Leão, Delfim. 2012. “The Eleusinian Mysteries and political timing in the Life of Alcibiades.” In Plutarch in the religious and philosophical discourse of late antiquity, edited by Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta, and Israel Muñoz Gallarte, 181–92. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004236851_014

- López, Eire A. 2002. Poéticas y retóricas griegas. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis.

- Mosconi, G. 2021. Democrazia e buon governo. Cinque tesi democratiche nella Grecia del V secolo a.C. Milano: Ed. Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

- Rhodes, P. J. 2006. “Thucydides and the Athenian history.” In Brill’s Companion to Thucydides, edited by Antonios Rengakos and Antonis Tsakmakis, 523–46. Leiden: Brill.

- Rhodes, P. J. 2007. A History of the Classical Greek World. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Rhodes, P. J. 2011. Alcibiades: Athenian Playboy, General and Traitor. Barnsely (South Yorkshire): Pen and Sword Military Books.

- Rogan, Esther. 2018. La stasis dans la Politique d’Aristote. Paris: Classiques Garnier. Romilly, Jacqueline de. 1995. Alcibiade. Paris: Éditions de Fallois.

- Rossetti, Livio, e Carlo Santaniello. 2004. Studi sul pensiero e sulla lingua di Empedocle. Bari: Levante.

- Ruzé, Françoise. 2006. “Spartans and the use of treachery among their enemies.” In Sparta & War, edited by Stephen Hodkinson, and Anton Powell, 267–85. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales.

- Strassler, Robert B., and Victor D. Hanson. 1996. The Landmark Thucydides. A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. New York: Free Press.

- Stuttard, David. 2018. Nemesis. Alcibiades and the Fall of Athens. Cambridge (Mass.)-London: Harvard University Press.

- Vickers, Michael. 1999a. “Alcibiades and Melos: Thucydides 5.84–116.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 48, 3: 265–81.

- Vickers, Michael. 2019b. Sophocles and Alcibiades. Athenian Politics in Ancient Greek Literature. London-New York: Routledge.

- Zahrnt, Michael. 2006. “Sicily and Southern Italy in Thucydides.” In Brill’s Companion to Thucydides, edited by Antonios Rengakos and Antonis Tsakmakis, 629–55. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047404842_026

Contribution (93-108) to Crises (Staseis) and Changes (Metabolai). Athenian Democracy in the Making, edited by Breno Battistin Sebastiani, Delfim Ferreira Leão (2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.