Investigating the earliest iconographic examples of writing practice given blurred boundaries between art and script.

By Dr. Rachele Pierini

Postdoctoral Researcher

Centre for Textile Research

University of Copenhagen

Introduction

In the earliest evidence for writing of the Aegean during the Bronze Age (2nd millennium BCE) there are blurred boundaries between art and script. Within this framework, a palaeographic study is also an iconographic inquiry, especially when undeciphered scripts are at play. This is the case of a set of signs referring to textiles in Cretan Hieroglyphic (c. 1900–1650 BCE), Linear A (c. 1800–1450 BCE) and Linear B (c. 1450–1200 BCE). LinearB is the only Aegean script to have been deciphered and records the earliest known form of the Greek language (Mycenaean), whereas the language that Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A encode (Minoan) is still poorly understood. This paper explores the relationship between iconography and textiles by focusing on textile logograms in the Aegean scripts. In particular, it analyses TELA+TE as a case study

During the archaeological excavation at the palace of Knossos on the island of Crete in 1900 CE, Arthur Evans brought to light epigraphic materials that provided evidence of hitherto unknown writing systems. By observing the shape of the inscribed signs, he quickly realised that three different writing systems were at play. He was also able to establish that all three writing systems were syllabic scripts with a strong logographic component and with signs for numerals. ‘Syllabograms’ represent phonetic unities whereas ‘logograms’ refer to complete words and thus have a specific value in that they identify objects or tangible realities. Both are expressed by means of drawings, which closely resemble the designed items in the case of logograms and the more stylised elements in the case of syllabograms. Numerals are expressed by means of vertical and horizontal strokes (units and tens, respectively).

Evans later named these scripts ‘Cretan Hieroglyphic’, Linear A and Linear B, and did so before the languages they encoded was known. He used the shape of the signs that made up these scripts to differentiate between the writing systems. He called ‘Cretan Hieroglyphic’ the writing system he interpreted as a sort of pictographic version of the Egyptian Hieroglyphs. He qualified the other two scripts as ‘linear’. The shapes of the two ‘linear’ scripts, when compared to the decorative and calligraphic signs of Cretan Hieroglyphic, appeared to be more squared and linear. Next, he distinguished the two ‘linear’ scripts by arguing that one was older and the other more recent. Accordingly, Evans named the first ‘Linear A’ and the second ‘Linear B’. Although this nomenclature is still in use, more recent research and the discovery of new materials have revealed many aspects of these scripts and, in some cases, profoundly reshaped the interpretation of these writing systems.1

Potential similarities between Cretan Hieroglyphic and Egyptian Hieroglyphic have long been dismissed and Cretan Hieroglyphic is currently understood to be a logo-syllabic writing system that shares about 20 out of 100 signs with Linear A. Moreover, elements of the Cretan Hieroglyphic routinely understood as decorative patterns have more recently been recognised instead to be an integral part of the writing system. This demonstrates just how fluid were the boundaries between iconography and script in the earliest writing systems.2 In particular, the debate is still ongoing as to whether some of the signs found on seals represent examples of a highly iconic script or of decorative elements.

Whereas Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A share only about a fifth of their signs with each other, Linear A and Linear B show a close palaeographic connection, sharing about 75% of the signs that make up their syllabaries. This characteristic has led to the conclusion that the two ‘linear’ writing systems are derived from one another, with Linear A having acted as a template for Linear B. However, this assumption has recently been challenged with the suggestion that it is more likely that a ‘soft’ process of script adaptation took place on the north coast of Crete because the Linear A from this area shows the closest palaeographic similarity to the earliest known evidence of Linear B.3

Against this background, it is worth focusing on those elements which have specific attributes. An element appearing in all three writing systems, for example, may offer up clues as to its meaning as might a sign that names an archaeological artefact, even though the script encoding it has yet to be deciphered. This paper will adopt this approach to investigate textile logograms by analysing TELA+TE,4 a particular LinearB textile type, and its palaeographic ancestors in Linear A and Cretan Hieroglyphic.

Iconography in Aegean Scripts, TELA+TE as a Case Study

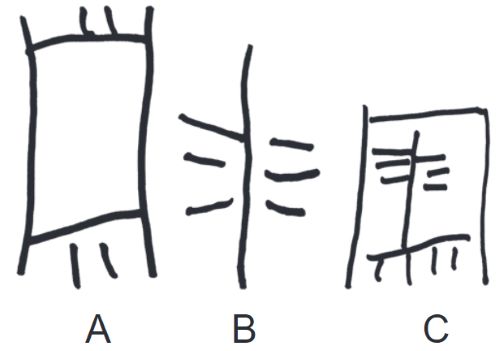

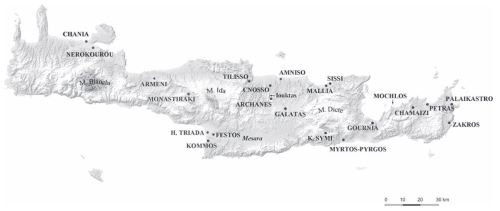

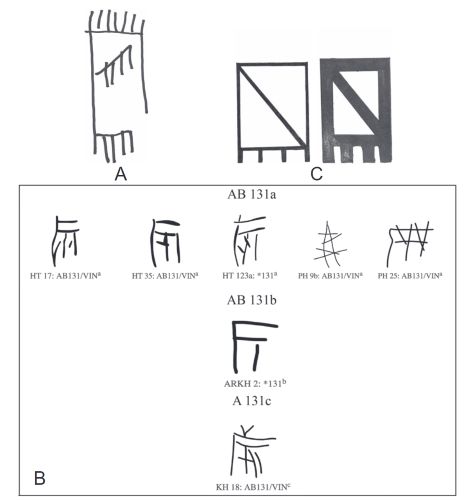

Iconography plays a major role in Aegean scripts because it is an integral part of the writing systems themselves. In particular, logograms have a direct connection with the material object they refer to. Their shape itself makes the item recognisable in the context of the text. For example, the logogram for ‘textile’ in Linear B (Fig.3.1.a), which is transcribed as TELA, represents a rectangular item with small vertical strokes at the bottom. This image immediately conveys information about the shape, which can be matched with the archaeological evidence.5 In Linear B texts, additional detail such as the fibre used to make the textile or the colour of the fabric are expressed syllabically, i.e. by means of words spelled out in full. In particular, a specific textile type can be expressed either syllabically or by means of ligatures. A ligature (or ligatured sign) is obtained by inserting an endogram into the logogram, i.e. a syllabic sign written inside the logogram to specify a particular kind of object. By adding the endogram TE inside the generic logogram tela, the ligature TELA+TE (Fig.3.1.c) refers to the particular textile type that, expressed syllabically, is te-pa.

The meaning of te-pa is a matter of debate in Mycenaean studies. Although it has been related to the alphabetic Greek τάπης ‘carpet’,6 such a comparison presents phonetic and morphological difficulties.7 There is another suggestion that has long gone unnoticed:8 te-pa could be the ancestor of the alphabetic Greek τήβεννα, i.e. the word that the Greek language uses for the Latin toga. From an etymological perspective, both τάπης and τήβεννα are loan words with Eastern origins and have an obscure formation.9 A renewed focus on the hypothesis of te-pa as τήβεννα together with additional Near East parallels have added further weight to the interpretation of te-pa as a textile or an item of clothing rather than a carpet.10

Within this framework, it is useful to focus on four key elements. First, Linear B inherited the scribal practice of ligature from Linear A. This makes this writing convention a feature common to both writing systems. Therefore, an analysis of the Linear A ancestor of tela+te is crucial to providing a better understanding of the particular textile to which the Linear B ligature refers. Second, in addition to the tight palaeographic connection between the two ‘linear’ scripts, the backward projection of Linear B phonetic values to Linear A signs is possible in c. 72% of AB signs, i.e. signs that share the same palaeographic shape and phonetic value.11 Signs constituting the Linear A ancestor of tela+te happen to fall within the group of those signs with a common phonetic value in both scripts, which are referred to as the AB signs. Third, although the language that LinearA and Cretan Hieroglyphic encode is scarcely intelligible, it is likely to be of non-Greek origins.12 The noun te-pa is not an Indo-European word; this makes its analysis in the non-Greek context that Linear A and Cretan Hieroglyphic document particularly appealing. Fourth, in dealing with scripts that are as yet undeciphered, images play a central role since they are particularly helpful in elucidating meaning in contexts that can still not be properly read. In particular, Linear A logograms, as well as signs used logographically, are a primary source of information for understanding these writing systems. Recent research has further enhanced the understanding of Linear A documents by highlighting the point that the size of a logogram and the disposition of its ligatured elements have a direct connection with the reading order of the signs involved.13

Given these circumstances, TELA+TE can be examined in the context of Linear B documents where both textual and iconographic analyses are possible. This paper will now compare Linear A and Cretan Hieroglyphic data on the ligature before using images to shed light on a context that would otherwise be unintelligible. It concludes by combining data from this analysis with the evidence from archaeological artefacts.

The TELA Logogram and the Ligature ‘TELA+TE’ in Linear B

Logogram *159 TELA ‘cloth’ (Fig.3.1.a) is the generic Linear B sign for textile. By incorporating the syllabogram te, sign 04 of the Linear B signary (Fig.3.1.b), inside the plain logogram tela, the ligature TELA+TE (Fig.3.1.c) is obtained. Syllabically, this item is referred to as te-pa. In Linear B texts, this type of textile is mainly referred to by means of the ligature TELA+TE14 whereas the full spelling te-pa appears in only a few documents.15

In the large dossier of TELA+TE, the drawing of the ligature appears to be quite uniform. The generic TELA logogram primarily has the shape of a main rectangular body with small vertical strokes at the bottom, two laterals and often one in the middle (Fig.3.1.a). Fringes that occasionally appear on its upper or lower edge account for scribal habits rather than textile quality.16 Thus, in its basic form, the TELA+TE ligature is made up of the telalogogram with the sign te placed inside the main rectangular space (Fig.3.1.c). The sign te, in turn, is constituted by a vertical stroke and three horizontal and detached strokes, on both the left and the right side (Fig.3.1.b).

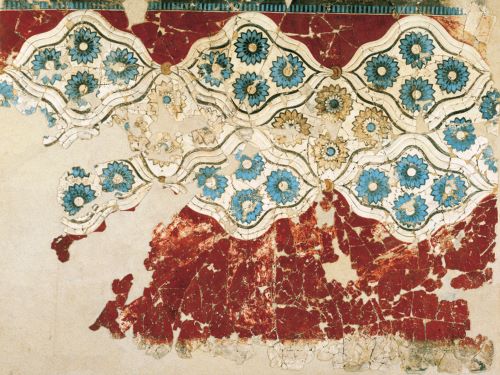

On the basis of this broad contextual information, te-pa has been interpreted as a textile made of sheep wool and characterised as being heavy, large and rectangular, an item occasionally given as compensation to people serving in the palace and sanctuaries.17 Moreover, te-pa is related to royal and ritual contexts18 and is often described as a red item.19 Because of the considerable amount of wool it requires, which is larger than any other Mycenaean textile, te-pa must indicate some kind of thick or heavy textile.20 Its use in royal contexts and its description as a red textile point toward the interpretation of te-pa not only as a proper dress, rather than a carpet, but also as clothing to be worn by prominent figures when carrying out their duties.21

The Linear A Ancestors: Signs AB 54 and AB 04

The sign AB 54 is commonly understood to be the palaeo-graphic ancestor of both the Linear B logogram *159 TELA and the syllabogram 54 (=wa). Both uses, syllabographic and logographic, are displayed also in Linear A. In addition, AB 54 is attested, as a logogram,22 in both its plain variant and ligatures.23 A slight difference in shape can be detected in AB 54 according to whether it is used as a syllabogram or a logogram inasmuch as the former is ‘linear’ and square (Fig.3.2.a) and the latter pictographic and round (Fig.3.2.c). Moreover, it is worth noting that Linear B wa (Fig.3.2.b) very closely resembles the shape of AB 54 used syllabically.

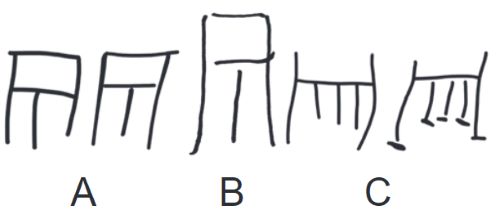

Not only does AB 04 belong to the large set of the homomorphic signs, it also happens to fall within the group of syllabograms of confirmed reading.24 Therefore, the phonetic value te can be inferred with some confidence on a comparative basis. In terms of its drawing, the main difference with the following Linear B sign 04 concerns the number and the orientation of the lateral strokes. Whereas Linear B te shows three horizontal and detached lines on each side of the stem (Fig.3.1.b), the lateral branches of AB 04 (Fig.3.3) might vary in number and orientation. The former ranges from a minimum of two to a maximum of six lines per side respectively on tablets such as ARKH 2.1 and HT 8a.3. The latter is drawn with either oblique or horizontal lines, with a slight preference given to oblique strokes (except on documents from Khania, in which lateral strokes are consistently drawn horizontally).25

The Ligature AB 54+AB 04 on the Tel Haror Inscription (TEL Zb 1)

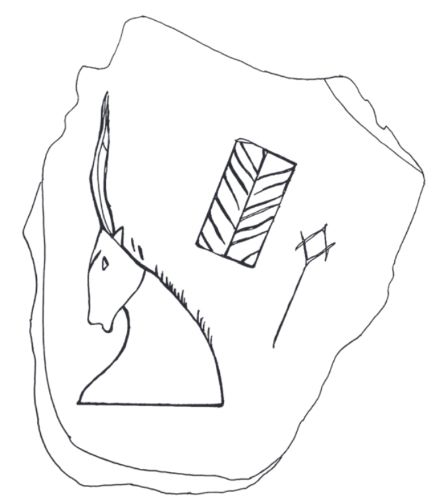

A potsherd from a handmade pithos found in the Tel Haror site (in the Negev Desert, Israel, about 20 km east of the Mediterranean Sea) is the only evidence of Aegean scripts found outside the Aegean area. The Tel Haror site has uncovered in areaK a building complex termed a cultic space because of the presence of features such as an offering altar, incense burners, zoomorphic vessels and human figurines. The pithos fragment TEL Zb 1, already broken in ancient times and without further sherds found nearby, can be dated to the late 17th or early 16th century BCE and interpreted as an ex-voto (Fig.3.4).26

Petrographic analyses have established its provenance to be the south coast of Crete (Myrtos Pyrgos) (Fig. 3.5). Epigraphic investigation has revealed that the three pre-fired incised signs the pithos fragment bears might be logograms representing commodities, namely – from left to right – a bull’s head, the ligature AB 54+04 and a fig-tree. The function of the sherd, the meaning of its inscription and even why it was present at the site of Tel Haror have yet to be explained.

The ligature AB 54+04 that the graffito sherd bears is directly comparable to Linear B TELA+TE.27 It remains a matter of debate as to whether this inscription belongs to the Cretan Hieroglyphic or to Linear A.28 It is also difficult to place the inscription within known Aegean palaeo-graphic traditions.29 The drawing of the endogram AB 04 on TEL Zb1 has two important elements: the number and the orientation of the lateral strokes. As already mentioned above, in the Linear B attestations the lateral strokes of AB04 are three in number and horizontally oriented, whereas these elements may vary in the Linear A documents, being up to six in number and both horizontally and obliquely orientated. A comparison of the data from the two ‘linear’ scripts reveals that LinearA attestations show both of these orientations in all the archives except for Khania (which only shows horizontally oriented lateral branches); by contrast, LinearB shows only the horizontal orientation. Interestingly, Khania is located on the north coast of Crete where the process of script adaptation from Linear A to Linear B is thought to have taken place.30 The inference here is that the oblique orientation is a palaeographic archaism that has not been carried over into Linear B. Similar inferences can be drawn by examining Linear A data from a diachronic perspective. It is significant that the two tablets showing the drawing of AB 04 with six lateral (and oblique) strokes all come from Hagia Triada and Phaistos, i.e. HT 8a.3 and PH 13c. Given that these two sites were located on the western end of the central part of Crete (Fig. 3.5), they can scarcely have contributed to the palaeographic development of the subsequent Linear B script since the process of script adaptation took place on the north coast of Crete.31 Taking into account this data on the palaeographic isolation of these two archives as well as the chronology of Linear A tablets from Phaistos (c.1750–1700 BCE), stratigraphically higher than the other Linear A deposits (c. 1500–1450 BCE),32 it could be argued that the oblique orientation of the lateral strokes of the sign AB 04 is a palaeographic archaism. Although there is still insufficient evidence to conclude with certainty that this data resolves the question of the script to which the Tel Haror sherd belongs, this consideration adds weight to the higher chronology of the artefact – and it offers a starting point from which to investigate further its palaeographic tradition.

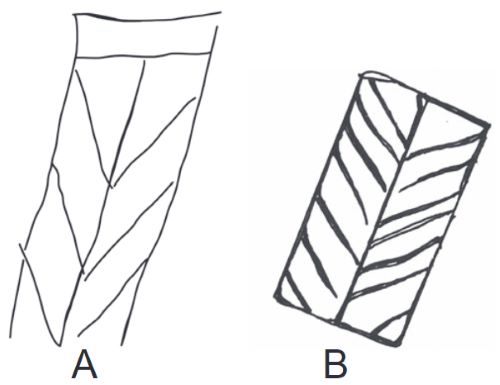

As Nosch points out,33 the ligature AB 54+04 has an appealing parallel in the ladies’ dresses on the 13th century BCE Tanagra larnax (small closed coffin or urn) (Fig.3.6).This artefact comes from the tomb 6 of the Gephyra cemetery at Tanagra from which more than 50 larnakes have come to light, most of them dated to Late Helladic period IIIA2-B (c. 1300 BCE, corresponding to the peak of the Mycenaean civilisation). The long side of the larnax on which the ladies’ dresses appear portrays five women pulling at their hair and with their mouths wide open to pronounce the funeral lament. The scene is a ritual procession of mourning women.34 Although there is insufficient evidence to fully sustain the comparison between the pattern of the ligature on TEL Zb1 and the ladies’ dresses on the Tanagra larnax, certain characteristics stand out. First, both artefacts are related to ritual, and ritual is also the content of the Linear B tablets that record tela+te. Second, if there is indeed a common origin for AB04 and the pattern on the Tanagra skirts, it might follow that the same feature has evolved following two different paths. On the one hand, the evolution of the scripts has progressively simplified the AB 04 drawing, from a sign with up to six lateral and oblique strokes in the earliest Linear A attestations to a sign with three horizontal lateral strokes on Linear B documents. On the other hand, the original shape might have been retained as such in the decoration of textile items such as the skirts used in ritual procession. If further research strengthens the likelihood of a relationship between the patterns on TEL Zb1 and the ladies’ dresses, which seem to resonate with one another, this would add weight to the hypothesis that iconography and script might have mutually influenced each other or have had a bi-directional course.35 Finally, should the relationship between the ligature on the sherd and pattern on the skirts be confirmed, this would strengthen the hypothesis that te-pa is a dress that was worn by people when performing their ritual roles.

Cretan Hieroglyphic Precursor(s)

The tela logogram appears to have had its palaeographic origin in Cretan Hieroglyphic logogram *163 (Fig.3.7.a), which is shown on the medallion CHIC #103.b, from the Dépôt hiéroglyphique at Malia and dated to the final phase of the Middle Minoan period (c. 1650 BCE). In its iconography, logogram *163 appears as a long and tiny rectangle with many fringes on both upper and lower sides. The sign inside it on #103.b does not correspond to any of the signs known thus far, thus making it difficult to decide whether it is an endogram. The comparison between the AB logogram for tela and the Cretan Hieroglyphic logogram *163 is a matter for debate, mainly because in the CHIC sign *163 is associated with AB 131 (Fig. 3.7.b). AB 131, in turn, is also linked to the sign041 (Fig. 3.7.c), which functions syllabically and has some differences in the way it has been drawn.36

A Different Connection?

Salgarella37 has pointed out that none of the representations of AB 131, coming in three different variants (AB 131a, AB 131b, AB 131c) throughout the corpus of Linear A inscriptions, exhibit the close vertical line on their upper right side shown in CHIC. However, it is worth making a further comparison by stressing the similarity between one of these variants as a ligatured sign, namely AB 131a+AB 04 [= A588] on KN Zb 34 (Fig.3.8.a), and the ligature on the Tel Haror sherd (Fig.3.8.b).38

Linear A logograms have recently been analysed on the basis of the size and position of the signs which form them. As a result, they have been distinguished in composite signs and ligatures.39 In the former case, the additional sign is a component of the logogram itself (and possibly of the spelled word as well) and is added as a smaller sign to the right of the biggest sign. In the latter case, the additional sign acts as an endogram since it is placed in the body of the main sign. According to this classification, both AB 131a+AB 04 [= A 588] on KN Zb 34 and AB 54+04 on TEL Zb 1 can be classified as ligatures in that they show a sign that is contained within the main logogram. There are further shared elements that merit additional comment. First, AB 131a+AB 04 [= A 588] corresponds to Vin+te, ‘wine’ being the commodity to which AB 131a refers. Next to the ligature AB 54 + AB 04, the graffito sherd records the logogram for the ‘fig-tree’, an agricultural product that – along with wine – was used in religious contexts and for ritual purposes.40 Second, both inscriptions are found on vessels (pithoi), a characteristic also underpinned by their classification as Zb. These data favour the interpretation of the ligature on the sherd as wine, given that pithoi were specifically meant to contain wine. In addition, the relationship between artefacts and the texts they bear is particularly secure if what is inscribed is either the owner’s name or the content of an item to be shipped.41 The latter seems to be the case with this potsherd, made in Crete and found on a Palestinian site. Finally, both inscriptions come from central Crete. Even though differing in number, the lateral branches present an oblique angle in both texts. It is noteworthy that data seem to show a connection between the orientation of the lateral strokes in sign AB 04 and the geographical origins of the inscription.

As mentioned earlier, within the Linear A corpus, lateral strokes of AB 04 might appear obliquely or horizontally positioned and some evidence suggests that such a disposition has a connection with the geographical provenance of the attestations.42 Located in the central part of the island, the site of Archanes has produced two examples of AB 04 with lateral lines that are obliquely oriented. Likewise, in inscriptions from east and southeast Crete, i.e. the deposits of Malia and Zakros, similar characteristics can be observed. Even though examples with horizontal branches are slightly more plentiful here, the oblique disposition is still prevalent. In the central sites of Knossos and Phaistos, as well as in the central-south deposit of Hagia Triada, despite a more uniform situation, a subtle preference for the oblique orientation can still be traced. In particular, in Hagia Triada, the oblique disposition appears highly prevalent on seals. The picture emerging for Khania, on the north coast of Crete, however, is drastically different. Texts from this site systematically show a fixed pattern in which AB 04 is regularly drawn with horizontal strokes that are consistently found in sets of three. This is exactly what can be seen in Linear B texts, where the only drawing thus far found of te shows horizontally oriented strokes in a set of three (cf. Fig. 3.1.b).

Conclusion

The case study of TELA+TE presented here highlights the range of criteria involved in understanding the use of iconography in the study of the Bronze Age Aegean scripts, where blurred boundaries between art and script characterise in particular the earliest attestations of the writing practice. Within this framework, the palaeographic analysis of a particular sign also becomes an iconographic inquiry, especially when dealing with scripts that have yet to be deciphered. The analysis of TELA+TE on the Linear B tablets, which are so far the only readable documents, has elucidated that te-pa is a loan word. The non-Greek origin of this noun, combined with the fact that evidence for the term is almost exclusively found in Knossos, fi ts perfectly within the Knossos textile terminology which – though plentiful – does not include Indo-European words, which are to be found only in documents from the mainland.43 It is also noteworthy that the attestations of the ligature significantly outnumber those of the spelled word. This might hint at the fact that particular Linear A scribal practices were still actively used on the island of Crete at the time of Linear B texts. Moreover, the palaeographic and iconographic analysis of the sign AB 04 adds further weight to the hypothesis that Linear A texts from the north coast of Crete show the closest similarity to the earliest known evidence of Linear B.

The development of Linear A might also be better understood by cross-checking palaeographic data from documents against the chronological data from archaeological sites. Furthermore, the analysis of the ligature throughout the corpus of Aegean scripts highlights the association between this feature and the ritual context. It would be tempting to include the ladies’ dress on the Tanagra larnax as a further example of this but, regrettably, there is still insufficient evidence to support this interpretation. However, exploring comparisons between texts and artefacts offers a cogent direction for future research. It may not be possible at this early stage in the research to conclusively demonstrate particular relationships, but further work will hopefully reveal new and exciting insights into the shapes, iconography, textiles and language of Bronze Age Crete.

Appendix

Endnotes

- For a recent overview of Cretan Hieroglyphic, Linear A and Linear B see, respectively, Karnava (2016); Perna (2016); Del Freo (2016).

- Ferrara et al. (2016); Decorte (2017).

- Salgarella (2018).

- Textile logograms are to be included among the archaeological artefacts after Nosch (2012, with further references and details, especially nn.5–7).

- Greek clothing is regularly based on a rectangular pattern, whereas other civilisations, e.g. the Romans, used a variety of forms: Bonfante Warren (1973, 585).

- DMic s.v. te-pa.

- Nosch (2012); Luján (2014); Pierini (2018).

- Peruzzi (1975).

- DELGs.vv. τάπης and τήβεννα as well as EDGs.vv. τάπης and τήβεννα.

- Pierini (2018).

- Steele and Meissner (2017).

- Duhoux (1978).

- Salgarella (2018).

- KN Ap5748, Lc525, 526, 527, 529, 530, 532, 533, 536, 541, 543, 547, 551, 553, 558, 561, 646, 5746, Le641, 642, 5629, 5646, 5903, 5930, 6014, Ln1568, L5660, 8160, Ws8153; PY La624, 1393, Un6. The sealing KN Wm 8493 might be added to this list: Driessen (2000, 209).

- KN L5090, Ws8153, X1432 and MY Oe107.

- Nosch (2012, 308–309).

- Nosch (2012, 325). Of the three different types of te-pa apparently shown by Linear B tablets, namely pe-ko-totela+te, mi-ja-ro tela+te and ‘unqualified’ tela+te (Firth 2012, 229), we can assume that both mi-ja-ro tela+te and ‘unqualified’ tela+terefer to the same type of textile, Killen (1987). Even though there may be insufficient documentation and technical knowledge to clearly understand its meaning, Del Freo etal. (2010, 357–358), pe-ko-to seems to denote textiles with the external side characterised by a hairy and fine appearance, Luján (1996–1997, 345–346); mi-ja-ro, on the other hand, could refer to uncombed woollen fabrics with a rough appearance (Firth 2012, 232) or dyed clothing (Luján 2010, 381).

- On KN Lc 525 it is specified that the recorded units of tela+te are wa-na-ka-te-ra ‘royal’, whereas on PY Un 6 the ligature appears together with two religious figures, namely i-je-re-ja ‘priestess(es)’ and ka-ra-wi-po-ro ‘key-bearer(s)’.

- In three entries these red items are specifically said to be for guests or foreigners: Firth (2012, 240).

- Sevenunits of wool are needed for the type tela+te, whereas the type pe-ko-to corresponds to ten units of wool: Nosch (2012, 325).

- Pierini (2018).

- For an in-depth description of AB54 used logographically and its contextual evidence, see Del Freo etal. (2010, 351–353).

- The syllabographic use of AB54 is to be found on PK Za11, HT6b.1, 36.2, 85b.4, 86.a3, 128.a2, Wc 3005, 3007, 3008, IO Za2a.1, MA10b.1, IO Za3, ARKH 2.5, ZA6.a1, 10b.1, TY3a.6 (see also Salgarella 2018). As a logogram, it appears in its plain variant on the roundel HT Wc3019 and the tablets HT 16.2, 20.4, whereas the ligatures are seen on THE8.2 (AB159+AB 09?) and twice on HT38.3, with two different endograms, respectively: AB159+AB81 (=A535) and AB159+AB312 (=A536).

- Olivier (1975); Godart (1984).

- Salgarella (2018).

- See further references and details in Oren (1993); Oren et al.(1996); Day et al. (1999); Olivier (1999, 2010); Karnava (2005); Del Freo etal. (2010); Nosch (2012); Petrakis (2012); Ferrara etal. (2016).

- Del Freo etal. (2010); Nosch (2012).

- Oren et al. (1996).

- Petrakis (2012, 78).

- Salgarella (2018). See also the introduction to this paper and what follows below.

- Salgarella (2018, in particular 162–171).

- Perna (2016, 93–94).

- Nosch (2012, 319).

- On this Tanagra larnax, see Demakopoulou and Konsola (1981, 85). For an in-depth analysis of the Tanagra larnakes, see, most recently, Kramer-Hajos (2015 with further references and details).

- Decorte (2017).

- Oren et al. (1996, 101–102 and n.6); Day et al. (1999); Karnava (2005); Del Freo etal. (2010); Nosch (2012).

- Salgarella (2018).

- Petrakis (2012).

- Salgarella (2018).

- Palmer (1994); Nagy (2019).

- Steele (2014).

- The dossier of AB 04 in the Linear A corpus is to be found in SigLA, which also reports the drawing of both the tablets and the signs. The attestations of the sign are presented according to the provenance of the documents. Source: https://sigla.phis.me/index.html (accessed 21 June 2021).

- Luján (1996–1997).

Bibliography

- Bernabé, A. and Luján, E. (2006) Introducción al griego micénico. Gramática, selección de textos y glosario. Zaragoza, Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

- Bonfante Warren, L. (1973) Roman Costumes: A Glossary and Some Etruscan Derivations. Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen WeltI 4, 584–614.

- Day, P.M., Oren, E.D., Joyner, L. and Quinn, P.S. (1999) Petrographic Analysis of the Tel Haror Inscribed Sherd: Seeking Provenance within Crete. In P. Betancourt, V. Karageorghis, R.Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds), MELETEMATA. Studies in Aegean Archaeology Presented to Malcolm H.Wiener as He Enters his 65th Year, Aegaeum 20, 191–196. Liège and Austin, Universitéde Liège and University of Texas at Austin.

- Decorte, R. (2017) Cretan ‘Hieroglyphic’ and the Nature of Script. In P. Steele (ed.), Understanding Relations Between Scripts: The Aegean Writing Systems, 33–56. Oxford and Philadelphia, Oxbow Books.

- Del Freo, M. (2016) La scrittura Linear B. In M. Del Freo and M. Perna (ed.), Manuale di epigrafia micenea. Introduzione allo studio dei testi in lineare B, 123–166. Padova, libreriau-niversitaria.it edizioni.

- Del Freo, M. and Perna, M. (eds) (2019) Manuale di epigrafia micenea. Introduzione allo studio dei testi in lineare B. 2nd edn [online]. Padova, libreriauniversitaria.it edizioni.

- Del Freo, M., Nosch, M.-L. and Rougemont, F. (2010) The Terminology of Textiles in the Linear B Tablets, Including Some Considerations on LinearA Logograms and Abbreviations. In C. Michel and M.-L. Nosch (eds), Textile Terminologies in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean from the Third to the First Millennia BC, 338–373. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Demakopoulou, K. and Konsola, D. (1981) Archaeological Museum of Thebes: Guide. Athens, General Direction of Antiquities and Restoration.

- Driessen, J. (2000) The Scribes of the Room of the Chariot Tablets at Knossos: Interdisciplinary Approach to the Study of the Linear B Deposit. Salamanca, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

- Duhoux, Y. (1978) Une analyse linguistique du linéaire A. In Y.Duhoux (ed.), Etudes minoennes, 65–129. Leuven, Peeters.

- Ferrara, S., Weingarten, J. and Cadogan, G. (2016) Cretan Hieroglyphic at Myrtos-Pyrgos. Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici Nuova Serie 2, 81–99.

- Firth, R. (2012) An Interpretation of the Specification of the Textiles on Ln 1568. In P. Carlier, C. de Lamberterie, M. Egetmeyer, N. Gilleux, F. Rougemont and J. Zurbach (eds), Études mycéniennes. Actes du XIII[e] colloque international sur les textes égéens, Sèvres, Paris, Nanterre, 20–23 septembre 2010, 229–241. Pisa and Roma, Fabrizio Serra Editore.

- Godart, L. (1984) Du linéaire A au linéaire B. In Centre Gustave Glotz (ed.), Aux origines de l’Hellénisme. La Crete e la Grèce. Hommage à Henri van Effenterre presente par le Centre G.Glotz, Série histoire ancienne et médiévale 15, 121–128. Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Karnava, A. (2005) The Tel Haror Inscription and Crete: A Further Link. In R. Laffineur and E. Greco (eds), Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean, 837–844. Liège, Université de Liège.

- Karnava, A. (2016) La scrittura ‘geroglifica’ cretese. In M. Del Freo and M. Perna (eds) Manuale di epigrafia micenea. Introduzione allo studio dei testi in lineare B, 63–86. Padova, libreriauniversitaria.it edizioni.

- Killen, J.T. (1987) Notes on the Knossos Tablets. In J.T. Killen, J.L. Melena and J.-P. Olivier (eds), Studies in Mycenaean and Classical Greek Presented to John Chadwick (Minos 20–22), 319–331. Salamanca, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

- Kramer-Hajos, M. (2015) Mourning on the Larnakes at Tanagra: Gender and Agency in Late Bronze Age Greece. Hesperia 84, 627–667.

- Luján, E. (1996–1997) El léxico micénico de las telas. Minos 31–32, 335–369.

- Luján, E. (2010) Mycenaean Textile Terminology at Work: The KN Lc(1)-Tablets and the Occupational Nouns of the Textile Industry. In C. Michel and M.-L. Nosch (eds), Textile Terminologies in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean from the Third to the First Millennia BC, 374–387. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Luján, E. (2014) Los temas en -s en micénico. In A. Bernabé and E. Luján (eds), Donum micenologicum. Mycenaean Studies in Honour of Francisco Aura Jorro, 51–73. Louvain-La-Neuve-Walpole, MA, Peeters.

- Nagy, G. (2019) Minoan and Mycenaean Fig Trees: Some Retrospective and Prospective Comments. Classical Inquiries. December 2019, Open Research Online. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/minoan-and-mycenaean-fig-trees-some-retrospective-and-prospective-comments/ (accessed 5July 2021).

- Nosch, M.-L. (2012) The Textile Logograms in the Linear B Tablets: Les idéogrammes archéologiques – des textiles. In P. Carlier, C. de Lamberterie, M. Egetmeyer, N. Gilleux, N.,Rougemont, F. and Zurbach, J. (eds), Études mycéniennes. Actes du XIII[e] colloque international sur les textes égéens, Sèvres, Paris, Nanterre, 20–23 septembre 2010, 303–344. Pisa and Roma, Fabrizio Serra Editore.

- Olivier, J.-P. (1975) ‘Lire’ le linéaire A. In J. Bingen, G. Cambier and G. Nachtergael (eds), Le monde grec: pensée, littérature, histoire, documents. Hommages à Claire Préaux, 441–449. Bruxelles, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Olivier, J.-P. (1999) Rapport 1991–1995 sur les textes en écriture ‘hiéroglyphique’ crétoise, en linéaire A et en linéaire B. In S.Deger-Jalkotzy, S. Hiller and O. Panagl (eds), Floreant Studia Mycenaea 2, 419–435. Wien, Verlage der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Olivier, J.-P. (2010) Les sceaux et scelles inédits en ‘hiéroglyphique’ crétois, en linéaire A et en linéaire B en Crète et en Grèce continentale, en chypro-minoen et dans les syllabaires du Ier millénaire à Chypre: un bilan. In W. Müller (ed.), Die Bedeutung der minoischen und mykenischen Glyptik, CMS Beiheft 8, 287–295. Mainz am Rhein, von Zabern.

- Oren, E.D. (1993) Tel Haror. In E. Stern (ed.), The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, 580–584. New York, NY, Simon and Schuster.

- Oren, E.D., Olivier, J.-P., Goren, Y., Betancourt, P., Myer, G.H. and Yellin, J. (1996) A Minoan Graffito from Tel Haror (Negev, Israel). Cretan Studies 5, 91–118.

- Palmer, R. (1994) Wine in the Mycenaean Palace Economy. Liège, Université de Liège.

- Perna, M. (2016) La scrittura Lineare A. In M. Del Freo and M.Perna (eds), Manuale di epigrafia micenea. Introduzione allo studio dei testi in lineare B, 87–114. Padova, libreriauni-versitaria.it edizioni.

- Peruzzi, E. (1975) Τήβεννα. Euphrosyne 7, 137–143. Petrakis, V. (2012) ‘Minoan’ to ‘Mycenaean’: Thoughts on the Emergence of the Knossian Textile Industry. In M.-L. Nosch and R. Laffineur (eds), KOSMOS. Jewellery, Adornment and Textile in the Aegean Bronze Age, Aegaeum 33, xxvi–xxvii and 77–86. Leuven and Liège, Peeters.

- Pierini, R. (2018) AB 54+04, Mycenaean te-pa, Alphabetic Greek τήβεννα, Latin toga: Semantic Remarks and Possible Near East Parallels. Journal of Latin Linguistics 17, 111–119.

- Salgarella, E. (2018) Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship between Linear A and Linear B. PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge.

- Steele, P. (2014) The Mystery of the Ancient Cypriot Clay Balls. British Academy Review 24, 60–63.

- Steele, P. and Meissner, T. (2017) From Linear B to Linear A: The Problem of the Backward Projection of Sound Values. In P. Steele (ed.), Understanding Relations Between Scripts: The Aegean Writing Systems, 93–110. Oxford and Philadelphia, Oxbow Books.

Chapter 3 (41-50) from Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography (Ancient Textiles Series 38), edited by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns AND Marta Zuchowska, (Oxbow Books, 02.03.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.