The medieval era was a time of hydraulic experimentation, adaptation, and diffusion.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Thirst for Innovation

The medieval period, stretching roughly from the 5th to the 15th century CE, is often imagined as a technologically stagnant era, especially in the Western imagination. Yet across the medieval world—from Europe to the Islamic caliphates, from South Asia to East Asia, Africa, and the Americas—societies developed and refined an impressive array of water technologies to meet the basic needs of agriculture, urban life, industry, and ritual. These technologies reveal not only pragmatic solutions to environmental constraints but also the circulation of ideas across regions through trade, conquest, and intellectual exchange.

Hydraulic Heritage in the Islamic World

Nowhere was water technology more advanced in the early medieval period than in the Islamic world. Drawing on Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian precedents, engineers in the Abbasid Caliphate and Andalusian Spain refined technologies such as the qanat (a subterranean channel system) and noria (a waterwheel powered by flowing water). The 9th-century engineer al-Jazari designed elaborate water-raising machines and described them in his Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, blending art and engineering. His works inspired both practical implementation and later Renaissance engineers.¹

In cities like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba, water was not only abundant but carefully managed. Urban water supplies included aqueducts, public fountains, and baths, with water distributed according to complex social hierarchies and municipal planning.

Water Management in Medieval Europe

In Europe, Roman aqueduct systems fell into decline after the collapse of the Western Empire, but medieval communities adapted. Monasteries became centers of hydraulic ingenuity, often installing systems for bathing, brewing, milling, and irrigation. Cistercian monks in particular developed complex canal networks to manage water for agriculture and proto-industrial use.²

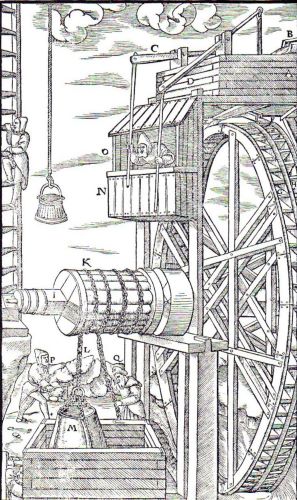

The spread of the horizontal waterwheel and the overshot vertical wheel revolutionized European milling in the 12th and 13th centuries. These mills were not only used for grinding grain but also for fulling cloth, powering bellows, and crushing ores. Legal disputes over mill rights and water diversion were frequent, underscoring the economic value of water power.

China: Hydraulic Sophistication and State Power

In medieval China, especially under the Song Dynasty (960–1279), water management reached remarkable heights. The state invested in large-scale canal construction, including the maintenance and expansion of the Grand Canal, which connected the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers to support grain transport and administrative control. Engineers such as Su Song and Shen Kuo documented water-powered astronomical instruments and mechanical clocks, representing the intersection of hydraulics with scientific advancement.³

Chinese cities featured public baths and irrigation systems, while rice cultivation in the south benefited from intricate dike and paddy systems that required careful seasonal management of water. The wheelbarrow, treadle pump, and chain pump were all widely used and exported to other parts of Asia.

India and the Subcontinent: Wells, Tanks, and Stepwells

In South Asia, where monsoonal patterns and seasonal rivers defined water availability, local communities constructed stepwells (baolis or vavs), tanks, and elaborate reservoir systems. These structures served not only utilitarian functions but also spiritual and aesthetic ones. The Rani ki Vav stepwell in Gujarat, built in the 11th century, is both a water reservoir and an architectural marvel.⁴

Irrigation in medieval India often relied on localized systems maintained by village communities or temple trusts. The Chola dynasty in southern India supported large-scale tank irrigation systems, essential for rice agriculture and deeply integrated with temple-based religious life.⁵

Africa and Indigenous Water Knowledge

In the Sahel and East Africa, medieval communities developed water harvesting techniques suited to arid conditions. The city of Timbuktu, for instance, relied on seasonal flooding and dug wells to support a thriving urban culture. In the Horn of Africa and along the Swahili coast, coral-stone cisterns and rooftop rainwater catchment systems were used to supplement scarce freshwater supplies.⁶

Indigenous African water knowledge was adapted to microclimates, often passed down through oral tradition and embodied in sacred groves, seasonal rituals, and social taboos regarding water use.

Mesoamerica: Canals, Chinampas, and Ritual Water Management

In Mesoamerica, particularly among the Maya and Aztec civilizations, water technology was crucial to urban and agricultural systems. The Maya, inhabiting a region with seasonal rainfall and limited surface water, developed chultuns (underground storage chambers), aguadas (man-made reservoirs), and complex drainage systems to sustain cities like Tikal and Calakmul.⁷

The Aztecs famously employed chinampas, or floating gardens, on the shallow lakes of the Valley of Mexico. These artificially constructed plots used canals for irrigation and transport and supported year-round agriculture. Water from Lake Texcoco was also managed through causeways, sluices, and aqueducts that brought spring water into the city of Tenochtitlán, one of the most advanced urban hydraulic systems in the pre-Columbian world.⁸

Water in Mesoamerica was not only utilitarian but deeply embedded in ritual and cosmology. Rain deities such as Tlaloc were central to public ceremonies, and control over water reinforced political and religious authority.

Conclusion: A Connected Hydraulic World

Rather than a period of stagnation, the medieval era was a time of hydraulic experimentation, adaptation, and diffusion. Water technologies developed independently and in dialogue across cultural boundaries. Whether through Islamic treatises, Buddhist temple tanks, or monastic mills, water shaped not only survival but also religious practice, economic life, and scientific discovery.

The medieval global world was one of shared challenges and diverse solutions—a reminder that innovation is often driven by necessity, shaped by culture, and sustained by knowledge exchange.

Appendix

Endnotes

- al-Jazari, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, trans. Donald R. Hill (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1974).

- Paolo Squatriti, Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400–1000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2: Mechanical Engineering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965).

- Vijaya Ramaswamy, “Water Management in India: Historical and Cultural Dimensions,” Studies in History 18, no. 1 (2002): 23–45.

- Kathleen D. Morrison, Fields of Victory: Vijayanagara and the Course of Intensification (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

- Toby Wilkinson, The Nile: A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present (New York: Vintage, 2015).

- Prudence M. Rice, Maya Political Science: Time, Astronomy, and the Cosmos (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004).

- Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, The Aztecs (London: Thames & Hudson, 1988).

Bibliography

- al-Jazari. The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Translated by Donald R. Hill. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1974.

- Glick, Thomas F. Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages: Comparative Perspectives on Social and Cultural Formation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo. The Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson, 1988.

- Morrison, Kathleen D. Fields of Victory: Vijayanagara and the Course of Intensification. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2: Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Water Management in India: Historical and Cultural Dimensions.” Studies in History 18, no. 1 (2002): 23–45.

- Rice, Prudence M. Maya Political Science: Time, Astronomy, and the Cosmos. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

- Squatriti, Paolo. Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400–1000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wilkinson, Toby. The Nile: A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present. New York: Vintage, 2015.

- Wittfogel, Karl A. Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.