Map of the Ancient Near East / Wikimedia Commons

Edited by Matthew A. McIntosh / 04.14.2016

Brewminate Editor-in-Chief

The Cradle of Civilization

Introduction

By Dr. Senta German

Faculty of Classics

Andrew W Mellon Foundation Teaching Curator, Ashmolean Museum

University of Oxford

Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (in modern day Iraq), is often referred to as the cradle of civilization because it is the first place where complex urban centers grew. The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

What’s In a Name?

Illustration from: Sir Austen Henry Layard, The Ninevah Court in the Crystal Palace, 1854

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed “the near east.” Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn’t have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West’s interests in the Biblical “Holy Land” that ancient Near Eastern materials have been be regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art. An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French 19th century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were discovered and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The excavations inspired The Nineveh Court at the 1851 World’s Fair in London and a style of decorative art and architecture called Assyrian Revival. Ancient Near Eastern art remains popular today; in 2007 a 2.25 inch high, early 3rd millennium limestone sculpture, the Guennol Lioness, was sold for 57.2 million dollars, the second most expensive piece of sculpture sold at that time.

A Complex History

The Euphrates River in 2005

The history of the Ancient Near East is complex and the names of rulers and locations are often difficult to read, pronounce and spell. Moreover, this is a part of the world which today remains remote from the West culturally while political tensions have impeded mutual understanding. However, once you get a handle on the general geography of the area and its history, the art reveals itself as uniquely beautiful, intimate and fascinating in its complexity.

Geography and the Growth of Cities

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

The region lacks stone (for building), precious metals and timber. Historically, it has relied on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture. Here, for the first time, thanks to ample food and a strong administrative class, the West develops a very high level of craft specialization and artistic production.

Cuneiform: An Introduction

From The British Museum

The earliest writing we know of dates back to around 3,000 B.C.E. and was probably invented by the Sumerians, living in major cities with centralized economies in what is now southern Iraq. The earliest tablets with written inscriptions represent the work of administrators, perhaps of large temple institutions, recording the allocation of rations or the movement and storage of goods. Temple officials needed to keep records of the grain, sheep and cattle entering or leaving their stores and farms and it became impossible to rely on memory. So, an alternative method was required and the very earliest texts were pictures of the items scribes needed to record (known as pictographs).

Writing, the recording of a spoken language, emerged from earlier recording systems at the end of the fourth millennium. The first written language in Mesopotamia is called Sumerian. Most of the early tablets come from the site of Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, and it may have been here that this form of writing was invented.

Early Writing Tablet recording the allocation of beer, 3100-3000 B.C.E, Late Prehistoric period, clay, probably from southern Iraq. © Trustees of the British Museum. The symbol for beer, an upright jar with pointed base, appears three times on the tablet. Beer was the most popular drink in Mesopotamia and was issued as rations to workers. Alongside the pictographs are five different shaped impressions, representing numerical symbols. Over time these signs became more abstract and wedge-like, or “cuneiform.” The signs are grouped into boxes and, at this early date, are usually read from top to bottom and right to left. One sign, in the bottom row on the left, shows a bowl tipped towards a schematic human head. This is the sign for “to eat.”

These texts were drawn on damp clay tablets using a pointed tool. It seems the scribes realized it was quicker and easier to produce representations of such things as animals, rather than naturalistic impressions of them. They began to draw marks in the clay to make up signs, which were standardized so they could be recognized by many people.

Cuneiform

From these beginnings, cuneiform signs were put together and developed to represent sounds, so they could be used to record spoken language. Once this was achieved, ideas and concepts could be expressed and communicated in writing.

Cuneiform is one of the oldest forms of writing known. It means “wedge-shaped,” because people wrote it using a reed stylus cut to make a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet.

Letters enclosed in clay envelopes, as well as works of literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh have been found. Historical accounts have also come to light, as have huge libraries such as that belonging to the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal (668-627 B.C.E.).

Cuneiform writing was used to record a variety of information such as temple activities, business and trade. Cuneiform was also used to write stories, myths, and personal letters.

The latest known example of cuneiform is an astronomical text from C.E. 75. During its 3,000-year history cuneiform was used to write around 15 different languages including Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Elamite, Hittite, Urartian and Old Persian.

Cuneiform Tablets at The British Museum

The department’s collection of cuneiform tablets is among the most important in the world. It contains approximately 130,000 texts and fragments and is perhaps the largest collection outside of Iraq.

The centerpiece of the collection is the Library of Ashurbanipal, comprising many thousands of the most important tablets ever found. The significance of these tablets was immediately realized by the Library’s excavator, Austin Henry Layard, who wrote:

They furnish us with materials for the complete decipherment of the cuneiform character, for restoring the language and history of Assyria, and for inquiring into the customs, sciences, and … literature, of its people.

The Library of Ashurbanipal is the oldest surviving royal library in the world. British Museum archaeologists discovered more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments at his capital, Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik). Alongside historical inscriptions, letters, administrative and legal texts, were found thousands of divinatory, magical, medical, literary and lexical texts. This treasure-house of learning has held unparalleled importance to the modern study of the ancient Near East ever since the first fragments were excavated in the 1850s.

Epic of Gilgamesh and The Flood Tablet

The Flood Tablet, relating part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, 7th century B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, 15.24 x 13.33 x 3.17 cm, from Nineveh, northern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum

The best known piece of literature from ancient Mesopotamia is the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary ruler of Uruk, and his search for immortality. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a huge work, the longest piece of literature in Akkadian (the language of Babylonia and Assyria). It was known across the ancient Near East, with versions also found at Hattusas (capital of the Hittites), Emar in Syria and Megiddo in the Levant.

This, the eleventh tablet of the Epic, describes the meeting of Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with all his precious possessions, his kith and kin, domesticated and wild animals and skilled craftsmen of every kind.

Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he released did not return, showing that the waters must have receded.

This Assyrian version of the Old Testament flood story is the most famous cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia. It was identified in 1872 by George Smith, an assistant in The British Museum. On reading the text he … jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself.’

Map of the World

Map of the World, Babylonian, c. 700-500 B.C.E., clay, 12.2 x 8.2 cm, probably from Sippar, southern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the center (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam and other places are also named.

The central area is ringed by a circular waterway labelled “Salt-Sea.” The outer rim of the sea is surrounded by what were probably originally eight regions, each indicated by a triangle, labelled “Region” or “Island,” and marked with the distance in between. The cuneiform text describes these regions, and it seems that strange and mythical beasts as well as great heroes lived there, although the text is far from complete. The regions are shown as triangles since that was how it was visualized that they first would look when approached by water.

The map is sometimes taken as a serious example of ancient geography, but although the places are shown in their approximately correct positions, the real purpose of the map is to explain the Babylonian view of the mythological world.

Observations of Venus

Cuneiform tablet with observations of Venus, Neo-Assyrian, 7th century B.C.E., from Nineveh, northern Iraq, clay, 17.14 x 9.20 x 2.22 cm (The British Museum)

Thanks to Assyrian records, the chronology of Mesopotamia is relatively clear back to around 1200 B.C.E. However, before this time dating is less certain.

This tablet is one of the most important (and controversial) cuneiform tablets for reconstructing Mesopotamian chronology before around 1400 B.C.E.

The text of the tablet is a copy, made at Nineveh in the seventh century B.C.E., of observations of the planet Venus made in the reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon, about 1000 years earlier. Modern astronomers have used the details of the observations in an attempt to calculate the dates of Ammisaduqa (reigned 1646-26 B.C.E.). Ideally this process would also allow us to date the Babylonian rulers of the early second and late third millennium B.C.E. Unfortunately, however, there is much uncertainty in the dating because the records are so inconsistent. This has led to different chronologies being adopted with some scholars favoring a “high” chronology while others adopt a ‘middle’ or ‘low’ range of dates. There are good arguments for each of these.

Scribes

Literacy was not widespread in Mesopotamia. Scribes, nearly always men, had to undergo training, and having successfully completed a curriculum became entitled to call themselves dubsar, which means “scribe.” They became members of a privileged élite who, like scribes in ancient Egypt, might look with contempt upon their fellow citizens.

Understanding of life in Babylonian schools is based on a group of Sumerian texts of the Old Babylonian period. These texts became part of the curriculum and were still being copied a thousand years later. Schooling began at an early age in the é-dubba, the “tablet house.” Although the house had a headmaster, his assistant and a clerk, much of the initial instruction and discipline seems to have been in the hands of an elder student; the scholar’s “big brother.” All these had to be flattered or bribed with gifts from time to time to avoid a beating.

Apart from mathematics, the Babylonian scribal education concentrated on learning to write Sumerian and Akkadian using cuneiform and on learning the conventions for writing letters, contracts and accounts. Scribes were under the patronage of the Sumerian goddess Nisaba. In later times her place was taken by the god Nabu whose symbol was the stylus (a cut reed used to make signs in damp clay).

Deciphering Cuneiform

The decipherment of cuneiform began in the eighteenth century as European scholars searched for proof of the places and events recorded in the Bible. Travelers, antiquaries and some of the earliest archaeologists visited the ancient Near East where they uncovered great cities such as Nineveh. They brought back a range of artifacts, including thousands of clay tablets covered in cuneiform.

Scholars began the incredibly difficult job of trying to decipher these strange signs representing languages no-one had heard for thousands of years. Gradually the cuneiform signs representing these different languages were deciphered thanks to the work of a number of dedicated people.

Confirmation that they had succeeded came in 1857. The Royal Asiatic Society sent copies of a newly found clay record of the military and hunting achievements of King Tiglath-pileser I (reigned 1114-1076 B.C.E.) to four scholars, Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, Julius Oppert and William H. Fox Talbot. They each worked independently and returned translations that broadly agreed with each other.

This was accepted as proof that cuneiform had been successfully deciphered, but there are still elements that we don’t completely understand and the study continues. What we have been able to read, however, has opened up the ancient world of Mesopotamia. It has not only revealed information about trade, building and government, but also great works of literature, history and everyday life in the region.

Writing Cuneiform

From The British Museum

Cuneiform Tablets

From the UCLA Library

Sumerian

Sumerian Art: An Introduction

By Dr. Senta German

Cities of ancient Sumer, photo Wikimedia Commons

The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is in Sumer that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk.

Uruk

Prehistory ends with Uruk, where we find some of the earliest written records. This large city-state (and it environs) was largely dedicated to agriculture and eventually dominated southern Mesopotamia. Uruk perfected Mesopotamian irrigation and administration systems.

An Agricultural Theocracy

Within the city of Uruk, there was a large temple complex dedicated to Innana, the patron goddess of the city. The City-State’s agricultural production would be “given” to her and stored at her temple. Harvested crops would then be processed (grain ground into flour, barley fermented into beer) and given back to the citizens of Uruk in equal share at regular intervals.

Reconstruction of the ziggurat at Uruk dedicated to the goddess Inanna (created by Artefacts/DAI, copyright DAI, CC-BY-NC-ND)

The head of the temple administration, the chief priest of Innana, also served as political leader, making Uruk the first known theocracy. We know many details about this theocratic administration because the Sumerians left numerous documents in the form of tablets written in cuneiform script.

Cuneiform tablet still in its clay case: legal case from Niqmepuh, King of Iamhad (Aleppo), 1720 B.C.E., 3.94 x 2″ (British Museum)

It is almost impossible to imagine a time before writing. However, you might be disappointed to learn that writing was not invented to record stories, poetry, or prayers to a god. The first fully developed written script, cuneiform, was invented to account for something unglamorous, but very important—surplus commodities: bushels of barley, head of cattle, and jars of oil!

The origin of written language (c. 3200 B.C.E.) was born out of economic necessity and was a tool of the theocratic (priestly) ruling elite who needed to keep track of the agricultural wealth of the city-states. The last known document written in the cuneiform script dates to the first century C.E. Only the hieroglyphic script of the Ancient Egyptians lasted longer.

A Reed and Clay Tablet

A single reed, cleanly cut from the banks of the Euphrates or Tigris river, when pressed cut-edge down into a soft clay tablet, will make a wedge shape. The arrangement of multiple wedge shapes (as few as two and as many as ten) created cuneiform characters. Characters could be written either horizontally or vertically, although a horizontal arrangement was more widely used.

Very few cuneiform signs have only one meaning; most have as many as four. Cuneiform signs could represent a whole word or an idea or a number. Most frequently though, they represented a syllable. A cuneiform syllable could be a vowel alone, a consonant plus a vowel, a vowel plus a consonant and even a consonant plus a vowel plus a consonant. There isn’t a sound that a human mouth can make that this script can’t record.

Probably because of this extraordinary flexibility, the range of languages that were written with cuneiform across history of the Ancient Near East is vast and includes Sumerian, Akkadian, Amorite, Hurrian, Urartian, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hatian and Elamite.

White Temple and Ziggurat, Uruk

By Dr. Senta German

Visible from a Great Distance

Archaeological site at Uruk (modern Warka) in Iraq (photo: SAC Andy Holmes (RAF)/MOD, Open Government Licence v1.0)

Uruk (modern Warka in Iraq)—where city life began more than five thousand years ago and where the first writing emerged—was clearly one of the most important places in southern Mesopotamia. Within Uruk, the greatest monument was the Anu Ziggurat on which the White Temple was built. Dating to the late 4th millennium B.C.E. (the Late Uruk Period, or Uruk III) and dedicated to the sky god Anu, this temple would have towered well above (approximately 40 feet) the flat plain of Uruk, and been visible from a great distance—even over the defensive walls of the city.

Digital reconstruction of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (modern Warka), c. 3517-3358 B.C.E. © artefacts-berlin.de; scientific material: German Archaeological Institute

Ziggurats

Remains of the Anu Ziggurat, Uruk (modern Warka), c. 3517-3358 B.C.E. (photo: Geoff Emberling, Flickr, by permission)

A ziggurat is a built raised platform with four sloping sides—like a chopped-off pyramid. Ziggurats are made of mud-bricks—the building material of choice in the Near East, as stone is rare. Ziggurats were not only a visual focal point of the city, they were a symbolic one, as well—they were at the heart of the theocratic political system (a theocracy is a type of government where a god is recognized as the ruler, and the state officials operate on the god’s behalf). So, seeing the ziggurat towering above the city, one made a visual connection to the god or goddess honored there, but also recognized that deity’s political authority.

Digital reconstruction of the two-story version of the White Temple, Uruk (modern Warka), c, 3517-3358 B.C.E. © artefacts-berlin.de; scientific material: German Archaeological Institute

Excavators of the White Temple estimate that it would have taken 1500 laborers working on average ten hours per day for about five years to build the last major revetment (stone facing) of its massive underlying terrace (the open areas surrounding the White Temple at the top of the ziggurat). Although religious belief may have inspired participation in such a project, no doubt some sort of force (corvée labor—unpaid labor coerced by the state/slavery) was involved as well.

The sides of the ziggurat were very broad and sloping but broken up by recessed stripes or bands from top to bottom (see digital reconstruction, above), which would have made a stunning pattern in morning or afternoon sunlight. The only way up to the top of the ziggurat was via a steep stairway that led to a ramp that wrapped around the north end of the Ziggurat and brought one to the temple entrance. The flat top of the ziggurat was coated with bitumen (asphalt—a tar or pitch-like material similar to what is used for road paving) and overlaid with brick, for a firm and waterproof foundation for the White temple. The temple gets its name for the fact that it was entirely white washed inside and out, which would have given it a dazzling brightness in strong sunlight.

The White Temple

The White temple was rectangular, measuring 17.5 x 22.3 meters and, at its corners, oriented to the cardinal points. It is a typical Uruk “high temple (Hochtempel)” type with a tri-partite plan: a long rectangular central hall with rooms on either side. The White Temple had three entrances, none of which faced the ziggurat ramp directly. Visitors would have needed to walk around the temple, appreciating its bright façade and the powerful view, and likely gained access to the interior in a “bent axis” approach (where one would have to turn 90 degrees to face the altar), a typical arrangement for Ancient Near Eastern temples.

Section through the central hall of the “White Temple,” digital reconstruction of the interior of the two-story version White Temple, Uruk (modern Warka), c, 3517-3358 B.C.E. © artefacts-berlin.de; scientific material: German Archaeological Institute

The north west and east corner chambers of the building contained staircases (unfinished in the case of the one at the north end). Chambers in the middle of the northeast room suite appear to have been equipped with wooden shelves in the walls and displayed cavities for setting in pivot stones which might imply a solid door was fitted in these spaces. The north end of the central hall had a podium accessible by means of a small staircase and an altar with a fire-stained surface. Very few objects were found inside the White Temple, although what has been found is very interesting. Archaeologists uncovered some 19 tablets of gypsum on the floor of the temple—all of which had cylinder seal impressions and reflected temple accounting. Also, archaeologists uncovered a foundation deposit of the bones of a leopard and a lion in the eastern corner of the Temple (foundation deposits, ritually buried objects and bones, are not uncommon in ancient architecture).

Interior view of the two-story version of the “White Temple,” Digital reconstruction of the White Temple, Uruk (modern Warka), c, 3517-3358 B.C.E. © artefacts-berlin.de; scientific material: German Archaeological Institute

To the north of the White Temple there was a broad flat terrace, at the center of which archaeologists found a huge pit with traces of fire (2.2 x 2.7m) and a loop cut from a massive boulder. Most interestingly, a system of shallow bitumen-coated conduits were discovered. These ran from the southeast and southwest of the terrace edges and entered the temple through the southeast and southwest doors. Archaeologists conjecture that liquids would have flowed from the terrace to collect in a pit in the center hall of the temple.

Archaeological Reconstructions

By Sebastian Hageneuer

PhD Candidate in Archaeology

University of Cologne

Reconstructions of ancient sites or finds can help us to understand the distant past. For non-academics, reconstructions offer a glimpse into that past, a kind of visual accumulation of scientific research communicated by means of images, models or even virtual reality. We see reconstructions in films, museums and magazines to illustrate the stories behind the historical or archaeological facts. For archaeologists like me however, reconstructions are also an important tool to answer unsolved questions and even raise new ones. One field where this is particularly true is the reconstruction of ancient architecture.

Early Reconstructions

Reconstruction drawing of Nimrud, the site of an ancient Assyrian palace, by James Fergusson for Sir Henry Layard, published in 1853. The columns depicted here were never found. The reconstruction is clearly influenced by what was known at that time of Greco-Roman architecture and by John Martin’s Fall of Nineveh (1829)

Since at least medieval times, artists created visual reconstructions drawn from the accounts of travelers or the Bible. Examples of this include the site of Stonehenge or the Tower of Babylon. Since the beginning of archaeology as a science in the mid-19th century, scientific reconstructions based on actual data were made. Of course, the earlier visualizations were more conjectural than later ones, due to the lack of comparable data at that time (for example, the image above).

The Three Building Blocks of Reconstructions

Remains of Building C in Uruk. Only a couple of mud-brick rows have survived to offer a basic ground plan. The building dates into the 4th millennium B.C.E. © German Archaeological Institute, Oriental Institute, W 10767, all rights reserved.

Since the end of the 19th century, reconstruction drawings evolved to be less conjectural and increasingly based on actual archaeological data as these became available due to increased excavations. Today we can not only look at reconstructions, we can experience them—whether as life-sized physical models or as immersive virtual simulations. But how do we create them? What are they made of? Every reconstruction is basically composed of three building blocks: Primary Sources, Secondary Sources, and Guesswork.

The first step toward a good visualization is to become aware of the archaeological data, the excavated remains—simply everything that has survived. This data is referred to as the Primary Sources—this is the part of the reconstruction we are most certain about. Sometimes we have a lot that survives and sometimes we only have the basic layout of a ground plan (above).

Technical reconstruction of Building C in Uruk. The southwestern part of the building is artificially cut open so we can see the inside (for example, the staircase). © artefacts-berlin.de; Material: German Archaeological Institute

Even when the Primary Sources are utilized, we often have to fill the gaps with Secondary Sources. These sources are composed of architectural parallels, ancient depictions and descriptions, or ethno-archaeological data. So, for example in the case of the Building C in Uruk (above), we know through Primary Sources, that this building was made of mud-bricks (at least the first two rows). We then have to look at other buildings of that time to find out how they were built. In the example above, the layout of the ground-plan shows us that this building was tripartite—a layout well known from this and other sites. We also look at contemporary architecture to understand how mud-brick architecture functions and to find out what certain architectural details might mean. Unfortunately, we don’t have any depictions or textual evidence that can help us with this example. Parallels from later times however show us that the unusual niches in the rooms suggest an important function.

After utilising all the primary and secondary sources, we still need to fill in the gaps. The third part of every reconstruction is simple Guesswork. We obviously need to limit that part as much as we can, but there is always some guesswork involved—no matter how much we research our building. For example, it is rather difficult to decide how high Building C was over 5000 years ago. We therefore have to make an educated guess based, for example, on the estimated length and inclination of staircases within the building. If we are lucky, we can use some primary or secondary sources for that too, but even then, in the end we need to make a subjective decision.

Reconstructions as a Scholarly Tool

Besides creating these reconstructions to display them in exhibitions, architectural models can also aid archaeological investigations. If we construct ancient architecture using the computer, we not only need to decide every aspect of that particular building, but also the relation to adjoining architecture. Sometimes, the process of reconstructing several buildings and thinking about their interdependence can reveal interesting connections, for example the complicated matter of water disposal off a roof.

These are only random examples, but clearly, the process of architectural reconstruction is a complex one. We, as the creators, need to make sure that the observer understands the problems and uncertainties of a particular reconstruction. It is essential that the viewer understands that these images are not 100% factual. As the archaeologist Simon James has put it: “Every reconstruction is wrong. The only real question is, how wrong is it?”

Standing Male Worshipper (Tell Asmar)

From Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Standing Male Worshipper (votive figure), c. 2900-2600 B.C.E., from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone, bitumen, 11 5/8 x 5 1/8 x 3 7/8″ / 29.5 x 10 cm, Sumerian, Early Dynastic I-II (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

Cylinder Seals

By Dr. Senta German

Signed with a Cylinder Seal

Cylinder Seal (with modern impression), royal worshipper before a god on a throne with bull’s legs; human-headed bulls below, c. 1820-1730 B.C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Cuneiform was used for official accounting, governmental and theological pronouncements and a wide range of correspondence. Nearly all of these documents required a formal “signature,” the impression of a cylinder seal.

A cylinder seal is a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse (intaglio) and hung on strings of fiber or leather. These often beautiful objects were ubiquitous in the Ancient Near East and remain a unique record of individuals from this era. Each seal was owned by one person and was used and held by them in particularly intimate ways, such as strung on a necklace or bracelet.

When a signature was required, the seal was taken out and rolled on the pliable clay document, leaving behind the positive impression of the reverse images carved into it. However, some seals were valued not for the impression they made, but instead, for the magic they were thought to possess or for their beauty.

Cylinder Seal with Kneeling Nude Heroes, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Cylinder Seal (with modern impression), showing Kneeling Nude Heroes, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The first use of cylinder seals in the Ancient Near East dates to earlier than the invention of cuneiform, to the Late Neolithic period (7600–6000 B.C.E.) in Syria. However, what is most remarkable about cylinder seals is their scale and the beauty of the semi-precious stones from which they were carved. The images and inscriptions on these stones can be measured in millimeters and feature incredible detail.

The stones from which the cylinder seals were carved include agate, chalcedony, lapis lazuli, steatite, limestone, marble, quartz, serpentine, hematite and jasper; for the most distinguished there were seals of gold and silver. To study Ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals is to enter a uniquely beautiful, personal and detailed miniature universe of the remote past, but one which was directly connected to a vast array of individual actions, both mundane and momentous.

Why Cylinder Seals are Interesting

Art historians are particularly interested in cylinder seals for at least two reasons. First, it is believed that the images carved on seals accurately reflect the pervading artistic styles of the day and the particular region of their use. In other words, each seal is a small time capsule of what sorts of motifs and styles were popular during the lifetime of the owner. These seals, which survive in great numbers, offer important information to understand the developing artistic styles of the Ancient Near East.

The second reason why art historians are interested in cylinder seals is because of the iconography (the study of the content of a work of art). Each character, gesture and decorative element can be “read” and reflected back on the owner of the seal, revealing his or her social rank and even sometimes the name of the owner. Although the same iconography found on seals can be found on carved stelae, terra cotta plaques, wall reliefs and paintings, its most complete compendium exists on the thousands of seals which have survived from antiquity.

Standard of Ur

From the British Museum

Standard of Ur, c. 2600-2400 B.C.E., 21.59 x 49.5 x 12 cm (British Museum)

The City of Ur

Postcard; printed; photograph showing archaeological excavations at Ur, with Arab workmen standing for scale in the excavated street of an early second millennium B.C.E. residential quarter © Trustees of the British Museum

Known today as Tell el-Muqayyar, the “Mound of Pitch,” the site was occupied from around 5000 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E. Although Ur is famous as the home of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham (Genesis 11:29-32), there is no actual proof that Tell el-Muqayyar was identical with “Ur of the Chaldees.” In antiquity the city was known as Urim.

The main excavations at Ur were undertaken from 1922-34 by a joint expedition of The British Museum and the University Museum, Pennsylvania, led by Leonard Woolley. At the center of the settlement were mud brick temples dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.E. At the edge of the sacred area a cemetery grew up which included burials known today as the Royal Graves. An area of ordinary people’s houses was excavated in which a number of street corners have small shrines. But the largest surviving religious buildings, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, also include one of the best preserved ziggurats, and were founded in the period 2100-1800 B.C.E. For some of this time Ur was the capital of an empire stretching across southern Mesopotamia. Rulers of the later Kassite and Neo-Babylonian empires continued to build and rebuild at Ur. Changes in both the flow of the River Euphrates (now some ten miles to the east) and trade routes led to the eventual abandonment of the site.

The Royal Graves of Ur

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, sat a rubbish dump built up over centuries. Unable to use the area for building, the people of Ur started to bury their dead there. The cemetery was used between about 2600-2000 B.C.E. and hundreds of burials were made in pits. Many of these contained very rich materials.

Cylinder seal of Pu-abi, c. 2600 B.C.E., lapis lazuli, 4.9 x 2.6 cm, from Ur © Trustees of the British Museum

In one area of the cemetery a group of sixteen graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The most complete tomb discovered belonged to a lady identified as Pu-abi from the name carved on a cylinder seal found with the burial.

The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to seventy-four such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

The Standard of Ur

Peace (detail), The Standard of Ur, 2600-2400 B.C.E., shell, red limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen (original wood no longer exists), 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm, Ur © Trustees of the British Museum

This object was found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above the right shoulder of a man. Its original function is not yet understood.

Leonard Woolley, the excavator at Ur, imagined that it was carried on a pole as a standard, hence its common name. Another theory suggests that it formed the soundbox of a musical instrument.

When found, the original wooden frame for the mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli had decayed, and the two main panels had been crushed together by the weight of the soil. The bitumen acting as glue had disintegrated and the end panels were broken. As a result, the present restoration is only a best guess as to how it originally appeared.

War (detail), The Standard of Ur, 2600-2400 B.C.E., shell, red limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen (original wood no longer exists), 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm, Ur © Trustees of the British Museum

The main panels are known as “War” and “Peace.” “War” shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army. Chariots, each pulled by four donkeys, trample enemies; infantry with cloaks carry spears; enemy soldiers are killed with axes, others are paraded naked and presented to the king who holds a spear.

The “Peace” panel depicts animals, fish and other goods brought in procession to a banquet. Seated figures, wearing woolen fleeces or fringed skirts, drink to the accompaniment of a musician playing a lyre. Banquet scenes such as this are common on cylinder seals of the period, such as on the seal of the “Queen” Pu-abi, also in the British Museum (see image above).

Queen’s Lyre

Leonard Woolley discovered several lyres in the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. This was one of two that he found in the grave of “Queen” Pu-abi. Along with the lyre, which stood against the pit wall, were the bodies of ten women with fine jewelry, presumed to be sacrificial victims, and numerous stone and metal vessels. One woman lay right against the lyre and, according to Woolley, the bones of her hands were placed where the strings would have been.

Queen’s Lyre (reconstruction), 2600 B.C.E., wooden parts, pegs and string are modern; lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone mosaic decoration, set in bitumen and the head (but not the horns) of the bull are ancient; the bull’s head in front of the sound box is covered with gold; the eyes are lapis lazuli and shell and the hair and beard are lapis lazuli; panel on front depicts lion-headed eagle between gazelles, bulls with plants on hills, a bull-man between leopards and a lion attacking a bull; edges of the sound-box are decorated with inlay bands; eleven gold-headed pegs for the strings, 112.5 x 73 x 7 cm (body), Ur © Trustees of the British Museum

The wooden parts of the lyre had decayed in the soil, but Woolley poured plaster of Paris into the depression left by the vanished wood and so preserved the decoration in place. The front panels are made of lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone originally set in bitumen. The gold mask of the bull decorating the front of the sounding box had been crushed and had to be restored. While the horns are modern, the beard, hair and eyes are original and made of lapis lazuli.

This musical instrument was originally reconstructed as part of a unique “harp-lyre,” together with a harp from the burial, now also in The British Museum. Later research showed that this was a mistake. A new reconstruction, based on excavation photographs, was made in 1971-72.

Perforated Relief of Ur-Nanshe

By Dr. Senta German

Perforated relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, limestone, Early Third Dynasty (2550–2500 B.C.E.), found in Telloh or Tello (ancient city of Girsu). 15-¼ x 18-¼ inches / 39 x 46.5 cm (Musée du Louvre)

Archaeologists believe that the years 2800-2350 B.C.E. in Mesopotamia saw both increased population and a drier climate. This would have increased competition between city-states which would have vied for arable land.

As conflicts increased, the military leadership of temple administrators became more important. Art of this period emphasizes a new combination of piety and raw power in the representation of its leaders. In fact, the representation of human figures becomes more common and more detailed in this era.

This votive plaque, which would have been hung on the wall of a shrine through its central hole, illustrates the chief priest and king of Lagash, Ur-Nanshe, helping to build and then commemorate the opening of a temple of Ningirsu, the patron god of his city. The plaque was excavated at the Girsu. There is some evidence that Girsu was then the capital of the city-state of Lagash.

Detail, Perforated relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, limestone, Early Third Dynasty (2550–2500 B.C.E.), found in Telloh or Tello (ancient city of Girsu). 15-¼ x 18-¼ inches / 39 x 46.5 cm (Musée du Louvre)

The top portion of the plaque depicts Ur-Nanshe helping to bring mud bricks to the building site accompanied by his wife and sons. The bottom shows Ur-Nanshe seated at a banquet, enjoying a drink, again accompanied by his sons. In both, he wears the traditional tufted woolen skirt called the kaunakes and shows off his broad muscular chest and arms.

Ziggurat of Ur

By Dr. Senta German

Ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 B.C.E. mud brick and baked brick, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (largely reconstructed)

The Great Ziggurat

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of Ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran, and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

Woolley Photo of the Ziggurat of Ur with workers Ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 B.C.E., Woolley excavation workers (Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq)

What Woolley found was a massive rectangular pyramidal structure, oriented to true North, 210 by 150 feet, constructed with three levels of terraces, standing originally between 70 and 100 feet high. Three monumental staircases led up to a gate at the first terrace level. Next, a single staircase rose to a second terrace which supported a platform on which a temple and the final and highest terrace stood. The core of the ziggurat is made of mud brick covered with baked bricks laid with bitumen, a naturally occurring tar. Each of the baked bricks measured about 11.5 x 11.5 x 2.75 inches and weighed as much as 33 pounds. The lower portion of the ziggurat, which supported the first terrace, would have used some 720,000 baked bricks. The resources needed to build the Ziggurat at Ur are staggering.

Moon Goddess Nanna

The Ziggurat at Ur and the temple on its top were built around 2100 B.C.E. by the king Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur for the moon goddess Nanna, the divine patron of the city state. The structure would have been the highest point in the city by far and, like the spire of a medieval cathedral, would have been visible for miles around, a focal point for travelers and the pious alike. As the Ziggurat supported the temple of the patron god of the city of Ur, it is likely that it was the place where the citizens of Ur would bring agricultural surplus and where they would go to receive their regular food allotments. In antiquity, to visit the ziggurat at Ur was to seek both spiritual and physical nourishment.

Clearly the most important part of the ziggurat at Ur was the Nanna temple at its top, but this, unfortunately, has not survived. Some blue glazed bricks have been found which archaeologists suspect might have been part of the temple decoration. The lower parts of the ziggurat, which do survive, include amazing details of engineering and design. For instance, because the unbaked mud brick core of the temple would, according to the season, be alternatively more or less damp, the architects included holes through the baked exterior layer of the temple allowing water to evaporate from its core. Additionally, drains were built into the ziggurat’s terraces to carry away the winter rains.

Hussein’s Assumption

US soldiers decend the Ziggurat of Ur, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq

The Ziggurat at Ur has been restored twice. The first restoration was in antiquity. The last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabodinus, apparently replaced the two upper terraces of the structure in the 6th century B.C.E. Some 2400 years later in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein restored the façade of the massive lower foundation of the ziggurat, including the three monumental staircases leading up to the gate at the first terrace. Since this most recent restoration, however, the Ziggurat at Ur has experienced some damage. During the recent war led by American and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein parked his MiG fighter jets next to the Ziggurat, believing that the bombers would spare them for fear of destroying the ancient site. Hussein’s assumptions proved only partially true as the ziggurat sustained some damage from American and coalition bombardment.

Akkadian

Art of Akkad: An Introduction

By Dr. Senta German

Map showing the approximate extension of the Akkad empire during the reign of Narâm-Sîn, yellow arrows indicate the directions in which military campaigns were conducted, photo Wikimedia Commons

This centralization was military in nature and the art of this period generally became more martial. The Akkadian Empire was begun by Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad (Akkad has not yet been located, though one theory puts it under modern Baghdad).

Head of an Akkadian Ruler

Head of Akkadian Ruler, 2250-2200 B.C.E. (Iraqi Museum, Baghdad – looted?)

This image of an unidentified Akkadian ruler (some say it is Sargon, but no one knows) is one of the most beautiful and terrifying images in all of Ancient Near Eastern art. The life-sized bronze head shows in sharp geometric clarity, locks of hair, curled lips and a wrinkled brow. Perhaps more awesome than the powerful and somber face of this ruler is the violent attack that mutilated it in antiquity.

Ur

The kingdom of Akkad ends with internal strife and invasion by the Gutians from the Zagros mountains to the northeast. The Gutians were ousted in turn and the city of Ur, south of Uruk, became dominant. King Ur-Nammu established the third dynasty of Ur, also referred to as the Ur III period.

Victory Stele of Naram Sin

From Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, 2254-2218 B.C.E., pink limestone, Akkadian (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

This monument depicts the Akkadian victory over the Lullubi Mountain people. In the 12th century B.C.E., a thousand years after it was originally made, the Elamite king, Shutruk-Nahhunte, attacked Babylon and, according to his later inscription, the stele was taken to Susa in what is now Iran. A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or relief carving.

Cylinder Seal with a Modern Impression

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cylinder seal and modern impression: nude bearded hero wrestling with a water buffalo; bull-man wrestling with lion, c. 2250–2150 B.C.E., Akkadian, Serpentine, 1.42″ / 3.61 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Babylonian

Babylonia: An Introduction

From The British Museum

On the River Euphrates

The “Queen of the Night” Relief, 1800-1750 B.C.E., Old Babylonian, baked straw-tempered clay, 49 x 37 x 4.8 cm © Trustees of the British Museum

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi (about 1790-1750 B.C.E.). He established control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria. The British Museum holds one of the iconic artworks of this period, the so-called “Queen of the Night.”

From around 1500 B.C.E. a dynasty of Kassite kings took control in Babylon and unified southern Iraq into the kingdom of Babylonia. The Babylonian cities were the centers of great scribal learning and produced writings on divination, astrology, medicine and mathematics. The Kassite kings corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaohs as revealed by cuneiform letters found at Amarna in Egypt, now in the British Museum.

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. Other Babylonian cities also flourished; scribes in the city of Sippar probably produced the famous “Map of the World” (see image above).

Babylonian Kings

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. There were two sets of fortified walls and massive palaces and religious buildings, including the central ziggurat tower. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the famous “Hanging Gardens.” However, the last Babylonian king Nabonidus (555-539 B.C.E.) was defeated by Cyrus II of Persia and the country was incorporated into the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire.

New Threats

Map of the World, Babylonian, c. 700-500 B.C.E., clay, 12.2 x 8.2 cm, probably from Sippar, southern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum

Babylon remained an important center until the third century B.C.E., when Seleucia-on-the-Tigris was founded about ninety kilometers to the north-east. Under Antiochus I (281-261 B.C.E.) the new settlement became the official Royal City and the civilian population was ordered to move there. Nonetheless a village existed on the old city site until the eleventh century AD. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Since 1958 the Iraq Directorate-General of Antiquities has carried out further investigations. Unfortunately, the earlier levels are inaccessible beneath the high water table. Since 2003, our attention has been drawn to new threats to the archaeology of Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

For two thousand years the myth of Babylon has haunted the European imagination. The Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens, Belshazzar’s Feast and the Fall of Babylon have inspired artists, writers, poets, philosophers and film makers.

Visiting Babylon

From Lisa Ackerman and Dr. Beth Harris

This video was produced in cooperation with the World Monuments Fund.

The Babylonian Mind

From The British Museum

Hammurabi: The King Who Made the Four Quarters of the Earth Obedient

By Dr. Senta German

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_w5NGOHbgTw

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi, basalt, Babylonian, 1792-1750 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving.

Babylonia at the time of Hammurabi

Hammurabi of the city state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets (a stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving). We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

The Ishtar Gate and Neo-Babylonian Art and Architecture

By Dr. Senta German

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, Babylon, c. 575 B.C.E., glazed mud brick (Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

The chronology of Mesopotamia is complicated. Scholars refer to places (Sumer, for example) and peoples (the Babylonians), but also empires (Babylonia) and unfortunately for students of the Ancient Near East these organizing principles do not always agree. The result is that we might, for example, speak of the very ancient Babylonians starting in the 1800s B.C.E. and then also the Neo-Babylonians more than a thousand years later. What came in between you ask? Well, quite a lot, but mostly the Kassites and the Assyrians.

The Assyrian Empire which had dominated the Near East came to an end at around 600 B.C.E. due to a number of factors including military pressure by the Medes (a pastoral mountain people, again from the Zagros mountain range), the Babylonians, and possibly also civil war.

A Neo-Babylonian Dynasty

Map of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Babylonians rose to power in the late 7th century and were heirs to the urban traditions which had long existed in southern Mesopotamia. They eventually ruled an empire as dominant in the Near East as that held by the Assyrians before them.

This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia) because Babylon had also risen to power earlier and became an independent city-state, most famously during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.).

In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

Architecture

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar (604-561 B.C.E.) largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar purportedly built the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran). Though mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman writers, the “Hanging Gardens” may, in fact, be legendary.

The Ishtar Gate (today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. The whole gate was covered in lapis lazuli glazed bricks which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

Towers of Babel

From The British Museum

Kassite Art: Unfinished Kudurru

By Dr. Senta German

Top level: Mesopotamian Gods in symbolic form, second level: animals and deities playing musical instruments (detail), “Unfinished” Kudurru, Kassite period, attributed to the reign of Melishipak, 1186–1172 B.C.E., found in Susa, where it had been taken as war booty in the 12th c. B.C.E. (Louvre)

Artistic Exchange

Map of Kassite Babylonia (photo: MapMaster, Wikimedia Commons)

During the 2nd millennium, the region of Mesopotamia, with Assyria in the north and Babylonia in the south, together with Egypt and the Hittite lands in what is now modern Turkey, grew strong and exercised surprisingly harmonious political relations.

For art, this meant an easy exchange of ideas and techniques, and surviving texts reflect the development of “guilds” of craftsmen, such as jewelers, scribes and architects.

Babylonia at this time was held by the Kassites, originally from the Zagros mountains to the north, who sought to imitate Mesopotamian styles of art. Kudurru (boundary markers) are the only significant remains of the Kassites, many of which show Kassite gods and activities translated into the visual style of Mesopotamia.

Combining Cultures

This Kudurru, considered unfinished because it lacks an inscription, would have marked the boundary of a plot of land, and probably would have listed the owner and even the person to whom the land was leased.

“Unfinished” Kudurru, Kassite period, attributed to the reign of Melishipak, 1186–1172 B.C.E., found in Susa, where it had been taken as war booty in the 12th century B.C.E. (Louvre)

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

Animals and deities playing musical instruments (detail), “Unfinished” Kudurru, Kassite period, attributed to the reign of Melishipak, 1186–1172 B.C.E., found in Susa, where it had been taken as war booty in the 12th century B.C.E. (Louvre)

The Kassites eventually succumbed to the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece, and as great as Egypt. This is a period characterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, most likely, plague. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Assyrian

Assyrian Art: An Introduction

By Dr. Senta German

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its expansions.

A Military Culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium, led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Ashurbanipal slitting the throat of a lion from his chariot (detail), Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions, gypsum hall relief from the North Palace, Ninevah, c. 645-635 B.C.E., excavated by H. Rassam beginning in 1853 (British Museum)

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

Luxurious Palaces

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Lion pierced with arrows (detail), Lion Hunts of Ashurbanipal (ruled 669-630 B.C.E.), c. 645 B.C.E., gypsum,Neo-Assyrian, hall reliefs from Palace at Ninevah across the Tigris from present day Mosul, Iraq (British Museum)

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

This silent video reconstructs the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (near modern Mosul in northern Iraq) as it would have appeared during his reign in the ninth century B.C.E. The video moves from the outer courtyards of the palace into the throne room and beyond into more private spaces, perhaps used for rituals.( Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art) According to news sources, this important archaeological site was destroyed with bulldozers in March 2015 by the militants who occupy large portions of Syria and Iraq.

Feats of Bravery

Ashurbanipal taking aim at a lion (detail), Lion Hunts of Ashurbanipal (ruled 669-630 B.C.E.), c. 645 B.C.E., gypsum,Neo-Assyrian, hall reliefs from Palace at Ninevah across the Tigris from present day Mosul, Iraq (British Museum)

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

The Destruction of Susa

Sacking of Susa by Ashurbanipal, North Palace, Nineveh, 647 B.C.E.

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa.

In this relief, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Military Victories and Exploits

Wall relief from Nimrud, the sieging of a city, likely in Mesopotamia, c. 728 B.C.E. (British Museum)

In the Central Palace at Nimrud, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III illustrates his military victories and exploits, including the siege of a city in great detail.

In this scene we see one soldier holding a large screen to protect two archers who are taking aim. The topography includes three different trees and a roaring river, most likely setting the scene in and around the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.

Assyrian Sculpture

From The British Museum

Protective Spirit Relief from the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, 883-859 B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, alabaster, 224 x 127 x 12 cm (extant), Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum. One of a pair which guarded an entrance into the private apartments of Ashurnasirpal II. The figure of a man with wings may be the supernatural creature called an apkallu in cuneiform texts. He wears a tasselled kilt and a fringed and embroidered robe. His curled moustache, long hair and beard are typical of figures of this date. Across the body runs Ashurnasirpal’s “Standard Inscription,” which records some of the king’s titles.

Although Assyrian civilization, centred in the fertile Tigris valley of northern Iraq, can be traced back to at least the third millennium B.C.E., some of its most spectacular remains date to the first millennium B.C.E. when Assyria dominated the Middle East.

Ashurnasirpal II

Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 B.C.E., from Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq, magnesite, 113 x 32 x 15 cm (The British Museum) This rare example of an Assyrian statue in the round was placed in the Temple of Ishtar Sharrat-niphi to remind the goddess Ishtar of the king’s piety. Ashurnasirpal holds a sickle in his right hand, of a kind which gods are sometimes depicted using to fight monsters. The mace in his left hand shows his authority as vice-regent of the supreme god Ashur. The carved cuneiform inscription across his chest proclaims the king’s titles and genealogy, and mentions his expedition westward to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.E.) established Nimrud as his capital. Many of the principal rooms and courtyards of his palace were decorated with gypsum slabs carved in relief with images of the king as high priest and as victorious hunter and warrior. Many of these are displayed in the British Museum.

Ashurnasirpal II, whose name (Ashur-nasir-apli) means, “the god Ashur is the protector of the heir,” came to the Assyrian throne in 883 B.C.E. He was one of a line of energetic kings whose campaigns brought Assyria great wealth and established it as one of the Near East’s major powers.

Ashurnasirpal mounted at least fourteen military campaigns, many of which were to the north and east of Assyria. Local rulers sent the king rich presents and resources flowed into the country. This wealth was use to undertake impressive building campaigns in a new capital city created at Kalhu (modern Nimrud). Here, a citadel mound was constructed and crowned with temples and the so-called North-West Palace. Military successes led to further campaigns, this time to the west, and close links were established with states in the northern Levant. Fortresses were established on the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and staffed with garrisons.

By the time Ashurnasirpal died in 859 B.C.E., Assyria had recovered much of the territory that it had lost around 1100 B.C.E. as a result of the economic and political problems at the end of the Middle Assyrian period.

Relief Panels

The Siege and Capture of the City of Lachish in 701 B.C.E., panel 8-9, South-West Palace of Sennacherib, Nineveh, northern Iraq, Neo-Assyrian, c. 700-681 B.C.E., alabaster, 182.880 x 193.040 cm (The British Museum) Part of a series which decorated the walls of a room in the palace of King Sennacherib (reigned 704-681 B.C.E.). The Assyrian soldiers continue the attack on Lachish. They carry away a throne, a chariot and other goods from the palace of the governor of the city. In front and below them some of the people of Lachish, carrying what goods they can salvage, move through a rocky landscape studded with vines, fig and perhaps olive trees. Sennacherib records that as a result of the whole campaign he deported 200,150 people. This was standard Assyrian policy, and was adopted by the Babylonians, the next ruling empire.

Later kings continued to embellish Nimrud, including Ashurnasirpal II’s son, Shalmaneser III who erected the Black Obelisk depicting the presentation of tribute from Israel.

The Dying Lion, panel from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal, c. 645 B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, alabaster, 16.5 x 30 cm, Nineveh, northern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum. Part of a series of wall panels that showed a royal hunt. Struck by one of the king’s arrows, blood gushes from the lion’s mouth. There was a very long tradition of royal lion hunts in Mesopotamia, with similar scenes known from the late fourth millennium B.C.E.

During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Assyrian kings conquered the region from the Persian Gulf to the borders of Egypt. The most ambitious building of this period was the palace of king Sennacherib (704-681 B.C.E.) at Nineveh. The reliefs from Nineveh in the British Museum include a depiction of the siege and capture of Lachish in Judah.

The finest carvings, however, are the famous lion hunt reliefs from the North Palace at Nineveh belonging to Ashurbanipal (668-631 B.C.E.). The scenes were originally picked out with paint, which occasionally survives, and work like modern comic books, starting the story at one end and following it along the walls to the conclusion.

The Assyrians used a form of gypsum for the reliefs and carved it using iron and copper tools. The stone is easily eroded when exposed to wind and rain and when it was used outside, the reliefs are presumed to have been protected by varnish or paint. It is possible that this form of decoration was adopted by Assyrian kings following their campaigns to the west, where stone reliefs were used in Neo-Hittite cities like Carchemish. The Assyrian reliefs were part of a wider decorative scheme which also included wall paintings and glazed bricks.

The reliefs were first used extensively by king Ashurnasirpal II (about 883-859 B.CE..) at Kalhu (Nimrud). This tradition was maintained in the royal buildings in the later capital cities of Khorsabad and Nineveh.

Lamassu from the Citadel of Sargon II

From Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Lamassu (winged human-headed bulls possibly lamassu or shedu) from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (now Khorsabad, Iraq), Neo-Assyrian, c. 720-705 B.C.E., gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

These sculptures were excavated by P.-E. Botta in 1843-44.

In the news: Irreplaceable Lamassu sculpture, Assyrian architecture and whole archaeological sites have recently been destroyed by militants that control large areas of Iraq and Syria. This tragedy cannot be undone and is an attack on our shared history and cultural heritage.

Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions

From Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions, gypsum hall relief from the North Palace, Ninevah, c. 645-635 B.C.E., excavated by H. Rassam beginning in 1853 (British Museum)

Persian

Ancient Persia: An Introduction

By Dr. Senta German

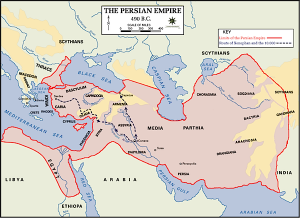

The Persian Empire, 490 B.C.E.

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century B.C.E., the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

A Tolerant Empire

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

Persepolis, photo: Matt Werner (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, the Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century B.C.E.

The Apadana

Assyrians with Rams, Apadana, Persepolis

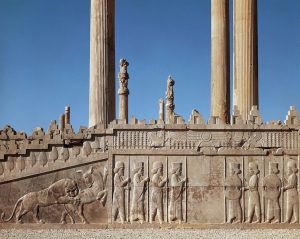

Persepolis included a massive columned hall used for receptions by the Kings, called the Apadana. This hall contained 72 columns and two monumental stairways.

Apadana staircase, Persepolis, Iran

The walls of the spaces and stairs leading up to the reception hall were carved with hundreds of figures, several of which illustrated subject peoples of various ethnicities, bringing tribute to the Persian king.

Conquered by Alexander the Great

The Persian Empire was, famously, conquered by Alexander the Great. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying the last Persian emperor, Darius III, in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

Capital of a Column from the Audience Hall of the Palace of Darius I, Susa

From Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Capital of a column from the audience hall of the palace of Darius I, Susa, c. 510 B.C.E., Achaemenid, Tell of the Apadana, Susa, Iran (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

By Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker

Mediterranean Archaeologist

Binghamton University, SUNY

Growth of the Achaemenid Empire under different kings / Wikimedia Commons

By the early fifth century B.C.E. the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth. Through regional administrators the Persian kings controlled a vast territory which they constantly sought to expand. Famous for monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous monumental centers, among those is Persepolis (today, in Iran). The great audience hall of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes presents a visual microcosm of the Achaemenid empire—making clear, through sculptural decoration, that the Persian king ruled over all of the subjugated ambassadors and vassals (who are shown bringing tribute in an endless eternal procession).

Kylix depicting a Greek hoplite slaying a Persian inside, by the Triptolemos painter, 5th century B.C.E. (National Museums of Scotland)

Overview of the Achaemenid Empire

Overview of Persepolis

Apādana

Bull Capital from Persepolis, Apādana, Persepolis (Fars, Iran), c. 520-465 B.C.E. (National Museum of Iran) (photo: s1ingshot, Flickr)

The Apādana palace is a large ceremonial building, likely an audience hall with an associated portico. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan, meaning that the roof of the structure is supported by columns. Apādana is the Persian term equivalent to the Greek hypostyle (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστυλος hypóstȳlos). The footprint of the Apādana is c. 1,000 square meters; originally 72 columns, each standing to a height of 24 meters, supported the roof (only 14 columns remain standing today). The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls (above), eagles or lions, all animals represented royal authority and kingship.

Apādana, Persepolis (Fars, Iran), c. 520-465 B.C.E. (photo: Alan Cordova, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The king of the Achaemenid Persian empire is presumed to have received guests and tribute in this soaring, imposing space. To that end a sculptural program decorates monumental stairways on the north and east. The theme of that program is one that pays tribute to the Persian king himself as it depicts representatives of 23 subject nations bearing gifts to the king.

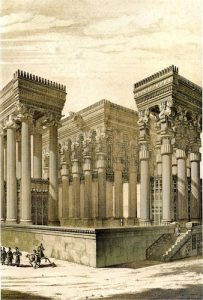

19th century reconstruction of the Apādana, Persepolis (Fars, Iran) by Charles Chipiez

The Apādana Stairs and Sculptural Program

The monumental stairways that approach the Apādana from the north and the east were adorned with registers of relief sculpture that depicted representatives of the twenty-three subject nations of the Persian empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king. The sculptures form a processional scene, leading some scholars to conclude that the reliefs capture the scene of actual, annual tribute processions—perhaps on the occasion of the Persian New Year–that took place at Persepolis. The relief program of the northern stairway was perhaps completed c. 500-490 B.C.E. The two sets of stairway reliefs mirror and complement each other. Each program has a central scene of the enthroned king flanked by his attendants and guards.

East stairway, Apādana, Persepolis (Fars, Iran), c. 520-465 B.C.E.

Noblemen wearing elite outfits and military apparel are also present. The representatives of the twenty-three nations, each led by an attendant, bring tribute while dressed in costumes suggestive of their land of origin. Margaret Root interprets the central scenes of the enthroned king as the focal point of the overall composition, perhaps even reflecting events that took place within the Apādana itself.

An Armenian tribute bearer carrying a metal vessel with Homa (griffin) handles, relief from the eastern stairs of the Apādana in Persepolis (Fars, Iran), c. 520-465 B.C.E. (photo: Aryamahasattva, Wikimedia Commons)