Ancient representations of the chemical arts are both varied and numerous.

Egypt

By Dr. Sydney H. Aufrère

Professor of Linguistics

Aix-Marseille University

Egyptian iconography included painted scenes, low-relief carvings, and stone statues or groups of wooden statues, showing how Egyptian craftsmen had mastered the chemical processes involved in the transformation of a large range of materials. Although here we treat only the most significant parts of the techniques used from the Old Kingdom to the Greco-Roman period, our discussion nonetheless provides an overview of the processes involved in such activities as bread-making, beer-brewing, drying, and salting, as well as metallurgical procedures, including goldsmithing, along with the manufacture of papyrus, perfumes, and aromatics. None of the scenes of processes used in ancient times was meant to fulfill a didactic role for craftsmen, since they were traditional parts of everyday life. The aim of this iconography was simply to keep the memory of these important activities alive forever, since they had provided the owner of the grave and his entourage with a high quality of life.

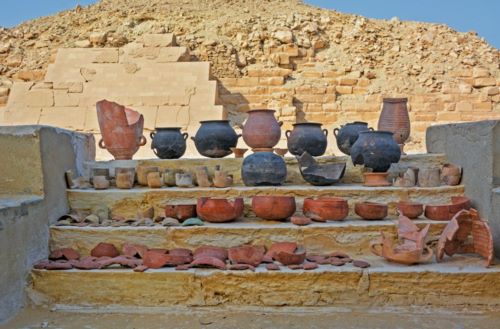

It seems that bread-making and beer-brewing (Samuel 2000) were carried out on a daily basis in the same workplace, be it for domestic use or on an industrial scale. To begin, both activities required mastery of the process of grinding cereals to obtain flour (Murray 2000). Women were in charge of the millstones used to grind cereals. Bakers then worked the dough on tabletops. Different processes to make bread and cakes were known and applied, depending on the season. Traditionally, bowls of leavened dough were placed in baked earthenware molds heated over a fireplace. The iconography shows the diversity of these molds along with slices of bread burned on the surface due to overheating. In the New Kingdom, round flat leavened dough was prepared and then slapped onto the walls of the oven, very much like in Egypt even today. The quality of cereals employed and the large number of recipes and cooking processes available permitted the making of a great variety of breads, examples of which have been found by archaeologists in the tombs of workers excavated in the village of Deir el-Medina.

According to pictures found in the tomb of Ti, the most common beer, of which there was a great variety, was brewed from ground barley (besha) and malt. Water was added to the barley, followed by wheat flour to prepare the dough, then this was baked. Loaves of baked dough were then triturated in water (the strength of alcohol depended on the amount of water added) in a large colander placed over a wide-bottomed jar used to gradually trap the liquid. The liquid was poured into vessels using a spout; these containers were then hermetically sealed and the liquid left to ferment. This recipe was so easy to follow that it is still used today to produce a beer called buza in Nubia or merissa in the Sudan (Helck 1971). The proportions of the ingredients were indicated (Helck 1971: 33–5), and a recipe for this same beer (called zythos/zythum) was also included in the work of Zosimos of Panopolis (third century ce; Helck 1971: 40; Mertens 1995: lix, n. 16; Nelson 2001: 124, 396) as well as in rabbinic literature (Bondi 1895). It seems that, depending on the amount of water added, state-owned breweries produced beers with different strengths of alcohol, which were measured in pesu; beers could be of small or high pesu, based on mathematical calculations (Papyrus Rhind, Papyrus of Moscow) that were also applied to mixtures of beers of different pesu (Couchoud 1988). But for everyone else, this recipe was simply for making bread and beer (Michel 2010).

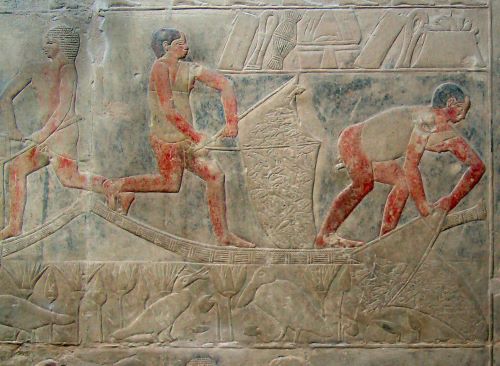

Wine-making comprised three stages: grape harvesting, crushing, and juice fermentation in jars (tomb of Nakht and Khaemuaset; Murray et al. 2000). Scenes of grape harvesting and of wine-making appeared early in the Old Kingdom, as shown in the tombs of Nyankhpepi or Mereruka. These tombs feature bunches of grapes that were cut from the climbing vines and collected in baskets. Full baskets were then emptied into tanks where barefoot men are depicted holding on to a central wooden bar while treading the grapes. The juice flowed into an underlying basin. In order not to lose any remaining must and to conclude the destemming, the residues of the treading were placed in a large sack, the ends of which were twisted by four men with the help of two wooden sticks, with a fifth man maintaining the spacing between the two sticks. The must thus squeezed also went into the jar, and all the must collected was then poured into fermentation jars and sealed with clay plugs (Varille 1938: 23–4, pl. XV).

At the end of the Thirty-First Dynasty, the tomb of Petosiris at Tuna el-Gebel, in Middle Egypt, added further details to this iconography by depicting other scenes of grape harvesting; the bunches are shown being harvested from climbing vines. According to the captions that accompanied the iconography, the operation proceeded nonstop from early morning when the dew was abundant, throughout the day, and only stopped at nightfall. The bunches of grapes were then deposited into a tank in which the grape-pickers, holding on to a fixed transverse wooden bar, treaded the grapes. The must flowed into a basin located below the treading tank, as shown by archaeological remains associated with the Mareotide vineyards (Redon et al. 2016). Must was then transferred into wide jars, which were counted by scribes and then brought to the master (Lefebvre 1923: 16–18, inscriptions nos. 43–4, pl. XII; Lefebvre 1924: 60–3; Cherpion et al. 2007: 58–63, scenes 56a–c).

Regarding the preservation of fish, the packing operations that took place after fishing are pictured in the mastabas of the Old Kingdom. Fish, degutted and visibly sliced at the dorsal ridge, were suspended for drying in the open air to ensure preservation (Vandier 1969: 635–58). It is very likely that sea salt and natron were used. It appears that ovaries of mullet fish, easily identified by their silhouette, were washed in salt water, the eggs collected and cured, and then finally packaged between two small wooden plates (Vandier 1969: 643–8).

From the Old Kingdom onwards, in the field of crafts, the work of metallurgists has been best explained by didactic scenes, while the knowledge of the technology of glassware and faience processing is only archaeological. From an iconographic point of view, only a few operations of the technology employed were depicted in pictures that had no didactic or practical value, because this knowledge had to be kept within specialized circles. In the New Kingdom, pictures in the tombs of Nakht and Rekhmirē‘ (TT 100) summarize the operations involved in metallurgy as follows: basin-shaped crucibles were placed on hearths into which the imported bronze oxhide-shaped ingots or loose ore were put to be smelted. The hearths were fanned to the required smelting temperature by means of air blasts using two cylindrical leather bellows strapped to the feet of a person (several could work at the same time) who operated them by alternately lifting one foot after the other. The crucible containing the molten metal was lifted by the metallurgists with the help of two tree branches, and the molten metal cast in a lost-wax mold was fed by several funnels, which were used to cast a temple gate several meters high for the sanctuary of Amon-Rē‘. In view of its purpose, this operation required mastery of the technique by the craftsmen (Garenne-Marot 1985).

Concerning goldsmithing, scenes in the tombs of Mereruka as well as of Nyankhkhnum and Khnumhotep at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) show that gold was melted after kindling the fire with blowpipes, through which workers blew air into an opening on one side of the hearth. The workers – dwarfs renowned for their skills – then presented the result of their work to the owner (Montet 1952a; Montet 1952b; Pons Mellado 2005; Dasen 2013: 89).

The tomb of Petosiris contained several scenes depicting the work of metallurgists and goldsmiths (Lefebvre 1923: 8–12, pl. VII–IX; Lefebvre 1924: 52–5; Cherpion et al. 2007: 34–5). However, the iconography is not sufficiently detailed to allow us to grasp the full meaning of the operations. In one scene, a coppersmith is shown using a pair of pliers to hold a piece of copper on a stone anvil while another is seen hammering it with a small stone. The caption states: “Men working copper to make the home of their master shine through their work.” Other scenes included goldsmiths hammering containers into shape, or smoothing them, on a side arm fixed to an anvil using a rudimentary mallet. Another operation shows silver and gold objects being polished. In order to avoid theft of precious metal, the objects were weighed on a balance with a mobile weight indicator, their weight recorded by scribes, and then the objects were locked in a wooden chest stored in the treasury.

Scenes depicting the preparation of perfumes are only meaningful when explanations are given in the texts. Thus the verb nud, “to cook” in Egyptian (Wb II: 226,8–9), referred to aromatists, called nudu. The Egyptian hieroglyph (Wb II: 226,10–11) depicted both the determinatives of the flame rising from a brazier and that of the aromatist preparing the perfume. Indeed, the preparation and quality of perfumes lay in the cooking of oils and fats on stoves for long periods of time. Etymologically speaking, the aromatists were therefore mainly “cookers” who had to strictly adhere to the cooking stages indicated.

The appellation of perfumers was given according to the different contexts in which they worked. The word ‘ānt (cf. “frankincense,” ‘ānty) showed that they were not preparers of incenses as such, but simply perfumers (Colin 2003). Moreover, according to its etymology, the texts mentioned the presence of a “perfume attendant” (iry-‘ānty; Colin 2003), a word suggesting that there was a hierarchy among aromatists. The second part of the composed word (‘ānty) stands for “frankincense,” generically referring to varieties of gum resins. The attendant was probably a person who had knowledge of both the essential components – a wide range of incenses, myrrh, and styrax – listed in the recipes of perfumes reproduced on the walls of temples’ so-called “laboratories” and also of the various aromatics used in their preparation. The word “frankincense” (‘ānty) in the title of “perfume attendant” embraced the entire spectrum of aromatic gum resins, namely sixteen categories, fourteen of which were of high quality and two of lower quality. In other words, the attendant supervised the production of perfumes, ensuring that books giving the recipes of perfumes were kept safe. His knowledge allowed him to distinguish between the different qualities of aromatic resins available on the market and thus prevent fraud, which was extremely frequent at the time. It is likely that the aromatists or cookers worked under his direction.

The elaborate techniques necessary to prepare perfumes or dyes, using both vegetable and mineral substances, implied the use of important and unknown chemical reactions later perfected by alchemy. Nonetheless, this in no way justifies the claim that ancient Egyptians mastered the indispensable distillation process, which was first documented only in the second century BCE (Forbes 1950; Kochmann 2014).

Scenes of flower-picking and perfume-manufacturing operations are scarce in Egyptian iconography. What depictions exist consist of succinctly presenting the process between picking and the final presentation of the finished product to the owner. There are a few scenes of lotus flower harvesting for the preparation of lotus ointment (Vandier 1969: 453–5). The plant grew in shallow marshy areas. After picking, the flowers were bagged for transport to the place of manufacture. In several tombs, scenes of perfume-making are pictured. In the tomb of the Vizier Kagemni (Fifth to Sixth Dynasties, 2510–2200 BCE) in Saqqara, four perfumers are pictured mixing oil and perfume in cylindrical travertine pots, the process being explained by captions. Several New Kingdom tombs of Thebes provide more information. In that of Amenmes (TT 89) at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, two men are seen filtering a substance with a strainer. The liquid is collected in a basin and then transported to two other perfumers responsible for overseeing the cooking of the oil in a container on a hotbed of embers (Shimy 1998: 336–7; El-Shahawy 2010: 131). In an anonymous grave (TT 175), scenes depict the pounding of the aromatics and the cooking of fat, a rare scene shows cold or hot enfleurage, and another one shows the filtering of the liquid by twisting a sack and the maceration of scented wood chips (styrax?) in oil (El-Shahawy 2010: 138). In the tomb of Qenamon (TT 93) in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, scenes show the mode of preparation of a mixture of various ingredients in a cooking pot placed on a stove and a man stirring the mixture with a stick (El-Shahawy 2010: 131).

Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, Louvre Museum, Wikimedia CommonsThe so-called “relief du lirinon” conserved in the Louvre Museum (inv. no. E 11377; Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, 672–525 Bce) evokes the sequence of operations to realize the essence of lily. Women are seen picking lilies in a field and putting them in baskets to keep them fresh. The flowers are then macerated in oil. The macerated flowers are then placed in a linen sack, and women are seen twisting the sack with the help of sticks to release the oil. According to a description by Pliny (23–79 ce; Plin. NH XXI 5), the “lily oil” or lirinon oozed into a jar placed on a support. The final product was then presented to the owner, Pairkap, also known as Psametikmerneith (Bénédite 1921; Desroches-Noblecourt 1975).

The tomb of Petosiris in Tuna el-Gebel shows a rare set of scenes of perfumers at work with specific but traditional instruments. A succession of operations are depicted: sorting, pounding, cooking, and checking the quality of the products, most with faulty captions or explanations that we will briefly try to interpret. Roughly speaking, the sequence was as follows: the contents of a sack of aromatics were spread on the ground where men are pictured sorting them out under the watchful eye of a scribe. These aromatics were then pounded in high-edged mortars or crushed on low tables. According to the recipes given in Edfu’s laboratory, the frankincense was first ground with a mortar. The aromatics and products of Punt were then added and the mixture was cooked in a cauldron resting on a cylindrical stove; a man is seen beating the firebox with a stick to keep the temperature constant while another man stirs the preparation with a stick. A caption clearly identifies this activity: “The perfumers who make frankincense with a sweet perfume.” The end product is then seen being poured into jars, then packaged and presented to the owner of the tomb for his use (Lefebvre 1923: 14–15, inscriptions nos. 37, 41, pl. X–XI; Lefebvre 1924: 58–9; Cherpion et al. 2007: 41–2, 47–9, inscriptions nos. 42–3). However, neither these scenes nor their captions fully cover the extreme complexity of these operations over time, which are clarified in the recipes kept at Edfu, Dendara, Kom Ombo, and Philae.

Mesopotamia

By Dr. Cale Johnson

Professor of Ancient History

Freie Universität Berlin

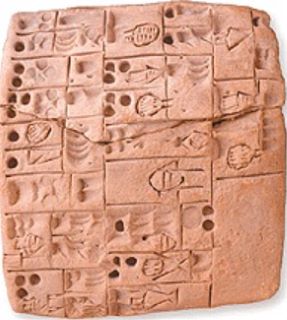

Just as the signs or characters in one writing system can be coincidentally identical to the graphemes in another (meaning that the significance of any grapheme must be rigorously demonstrated in its originating context), the use and significance of tools, installations, and other artifacts must likewise be demonstrated. The simple fact that a sieve can be used in a specifically chemical process, for instance, does not in itself demonstrate that this was its primary use: it could just as well (and more parsimoniously) have functioned as a kitchen colander or steamer. If we peruse the secondary literature on the history of chemistry in Mesopotamia, many of Martin Levey’s numerous shorter papers amount to arguments from the shape or possible function of vessels alone. Unusual forms of pottery, whether a vessel with a very low spout (Levey’s “drip bottle”) or the double-rimmed vessel from Tepe Gawra that appears in a number of his articles, could well have been developed for a specifically chemical process, but Levey provides no evidence for this from archaeological context (including residues) or iconography.

It is useful to keep Jean Bottéro’s work on cooking recipes firmly in mind whenever we need to review Levey’s proposals: is there any possible use of an unusual vessel for cooking a particular type of food? The most promising example of specifically technical artifacts are the copper-working tools from Tell edh-Dhiba’i, in the suburbs of present-day Baghdad. Christopher Davey’s work on these materials presents us with an ideal demonstration. They were excavated from a site that included waste products from the production and manipulation of metals, and some of the tools themselves, such as crucible 4, were found to contain residues of “copper, tin, arsenic and traces of iron and nickel. The crucibles were therefore used for the melting of bronze” (Davey 1983: 174). Davey goes on to describe technological parallels from Egypt and surveys the iconographic evidence for the particular form of crucible found in Tell edh-Dhiba’i, namely the scene from the Tomb of Mereruka at Saqqara (Davey and Edwards 2007: 147).

As was the case with Davey’s work on the crucibles from Tell edh-Dhiba’i, work on technological procedures in Mesopotamia and Syria must often look to depictions of these processes from outside of the region, typically to Egypt or even the Greco-Roman world. There are only a few depictions of “production processes” in reliefs and on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia, and these are, for the most part, early and focus primarily on agricultural or food production activities rather than specifically chemical ones. The Early Dynastic IIIb (ca. 2500–2400 BCE) milking scene from the Temple of Ninhursag in Ubaid (IM 513) is the most famous example, including the milking of the cows and the processing of dairy fats in vessels that correspond to the proto-cuneiform signs UKKINa and DUGb (Gouin 1993: 136–7; but see Englund 1998: 159–60 for the proto-cuneiform parallels).

There are, however, even earlier depictions of craft or processing activities in cylinder seals from Iran in the second half of the fourth millennium BCE, such as pottery-making or weaving, although it is often difficult to identify the specific activity or the tools involved.

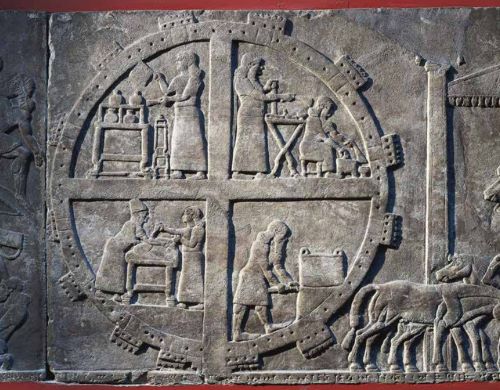

Although there are a few other images of processing activities such as butchering or the processing of dairy fats, the only other major sources of iconographic representations of these kinds of activities are found in depictions of military camps from the Neo-Assyrian reliefs. The workshops of the encamped military were obviously a point of pride for Neo-Assyrian rulers, and they appear in a number of different reliefs from their palaces. The best known of these is the circular depiction from the throne room of Assurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace (865–860 BCE). As Bottéro described it:

a bird’s eye view revealing the ground plan of a fortress and a cross section showing the activity within four chambers of the building. The four scenes include (beginning in the upper left and continuing counter-clockwise) a person opening wine jars to let them breathe, two people in the butcher’s shop where a sheep is being dressed, a baker tending his oven and two women preparing various foods.

Bottero 1985: 39; see the detail photograph in Brereton 2018: 91

Other depictions from Neo-Assyrian reliefs, such as the scenes from camp life in IM VA 965, are less iconic in their framing of the context, but the representations are very similar (Marriott and Radner 2015: 136). A rare depiction of nonmilitary life comes from contemporary (ca. 800–600 BCE) Iran, in the relief fragment known as “the Spinner,” in which an elite woman spins thread in what looks like a ritual or performative context. Of course, for our purposes here the salient characteristic of these depictions is that none of them relate directly to specifically chemical procedures.

If only to provide a foundation for what follows, it is best to start with the deities associated with the kiln, the vat, and the womb. For the kiln, or more broadly the oven, the deities of torch and censer, namely Gibil (a.k.a. Girra) and Kusu, are probably the most relevant. The bulk of the incantations associated with Gibil and Kusu focus on cultic purification of one kind or another (often summarized under the rubric of Kultmittelbeschwörungen in the specialist literature), and in Michalowski’s foundational “Torch and Censer” paper (1993), there are numerous sites for this act of purification:

Gibil raised his judicious head towards the heavens.

Michalowski 1993: 156

He takes hold of water from the holy teats of the heavens;

That water purifies the heavens, it cleanses the earth!

It cleanses the ox in the stall,

It cleanses the sheep in its pen,

It cleanses Utu at the base of the heavens,

It cleanses Nanna at heaven’s zenith!

But the more relevant part of this same incantation tradition is the role of the oven. In an incantation dedicated to the god of the censer, Kusu (but beginning with the god of the torch, Gibil), we hear of a list of ingredients (“cedar, cypress, zabalum, and boxwood, / white wool, black wool, black kin-tree and white kin-tree, / a string of dried apples and dried figs tied to a long string, / ibex horn and ghee”) that have been purified by the torch. After a break, the incantation pronounces that “the oven has been purified, the oven has been made holy.” The censer god Kusu then puts “abundant sheep and oxen into the mighty oven,” and the incantation concludes with the cleansing of pen, stall, the base of heaven, and its zenith that we looked at a moment ago.

And since the deity at the center of the glassmaking ritual from Oppenheim’s Alpha group is almost certainly Kusu, it is little wonder that there are numerous parallels between the Kusu Hymn and ritual for the foundation of a kiln. Here is Oppenheim’s translation, with Kusu substituted for Kubu:

As soon as you have completely finished [putting the kiln in place], you place (there) the [Kusu]-images, no outsider or stranger should (thereafter) enter (the building), an unclean person must not (even) pass in front of them (the images). … On the day when you plan to place the “stone” in the kiln, you make a sheep sacrifice before the [Kusu]-images, you place juniper incense on the censer and (then only) you make a fire in the hearth of the kiln and place the “stone” in the kiln.

transl. after Oppenheim 1970: 32–3, all occurrences of dku3-bu in this passage are probably to be read as dku3.su13

Ovens and kilns often function metaphorically as contexts of transformation, much like the vat and womb elsewhere in Mesopotamian literature, as, for example, in the phrase “the oven of humankind” in The Class Reunion, line 72 (Johnson and Geller 2015: 195–6).

We will turn to the beer-making vat below, but here we should also look at the deities and iconography associated with the womb. The pregnancy- and birth-related goddesses have been admirably surveyed in Frymer-Kinsky’s In the Wake of the Goddesses (1992) and Stol’s Birth in Babylonia and the Bible (2000), and need not be rehearsed here. More recently, however, Ulrike Steinert and Erica Couto-Ferreira have devoted a number of studies to the metaphors associated with the female body, and in particular the womb.

Here we see the mother goddess symbolized with the heads of babies sprouting from her shoulders, and on either side the so-called “omega” symbol above the crouched and emaciated body of an Akk. kūbu “fetus-demon.” As Steinert summarizes the situation:

The central symbol of the mother goddess … is the symbol resembling the Greek letter Omega, depicted on numerous seals from Mesopotamia, Syria, Anatolia and the Levant … The identification of the “omega” symbols as an emblem of the mother goddess was already established by William Hinke (1907: 95, 121) who noticed that on the kudurrus the symbol regularly appears in the fourth position, beside the senior divine male triad (Anu, Enlil and Enki), which corresponds with the position of Ninhursaga/Ninmah in some of the lists of deities in the curse section of the kudurru inscriptions. Although a number of interpretations of the symbol have been suggested, Henry Frankfort’s reading, corroborated by Egyptian parallels, as the schematic representation of the bicornate uterus of a cow remains the most generally accepted.

Steinert 2017: 207

The omega symbol, therefore, as a representation of the reproductive system of a cow, ties together the many different metaphors involved in childbirth incantations and rituals, such as the frequent use of bovine imagery.

The dominant metaphor for the womb in literary sources is agricultural, and this metaphor finds its prototypical expression in the myth known as Enki and Ninhursag; the womb (represented by Sum. ša3 “belly, womb, insides”) combines with semen (represented by Sum. a “water, semen”) to form, in the minds of the literati, Sum. a.ša3 /ašag/ “agricultural field.” And it is, after all, in Enki and Ninhursag that we find the earliest etiology for difficult childbirth (and the role of the midwife) in Mesopotamian literature. The text plays with the orthographic ambiguity of the two cuneiform signs ŠA3 and A in various ways, but most dramatically in the account of the matrilineal genealogy in which Enki, the god of fresh water, wisdom, and the technical crafts, fathers a line of female goddesses, each with a “womb” (Sum. ša3) that is an order of magnitude smaller than her predecessor. This leads invariably to the figure of Uttu, the goddess of weaving, whose womb is too small to give birth, obligating the mother goddess to extract Enki’s ever-fecund semen.

In the technical literature, however, primarily involving incantations found in first-millennium BCE medical compendia, a number of metaphors are used to describe the womb as a container filled with liquid: a waterway in a dammed-up meadow, the image of a waterskin, and that of a fermenting vat (Steinert 2013: 10). These metaphors were often extended to express the dangers of a leaky womb, such as in BAM 237 ii 1′–6′ and parallels, in terms of “a fermenting vat whose stopper is defective or a water-skin whose knot and drawstring are failing” (Steinert 2013: 10). Similar metaphors are found in compendia dedicated to the treatment of illnesses of the digestive tract, and there are numerous other similarities between these two groups of materials. Perhaps the most important feature of the metaphors used to describe these unseen domains within the body is that they are conceptualized as containers for liquids, often fermented alcoholic beverages, but they are not conceptualized primarily in terms of cooking, and are therefore quite different, in this respect, from Greco-Roman materials (see Stol 2006).

In both of these domains, literary and technical (although much more transparently in the technical materials), the dominant metaphor, in terms of the George Lakoff-Mark Johnson conceptual metaphor theory, is THE BODY IS A CONTAINER (by convention conceptual metaphor theory puts distinct metaphors in capital letters). This idea is at the center of a number of the contributions to The Comparable Body, a conference volume edited by John Wee that appeared in 2017. Indeed, Steinert’s contribution to The Comparable Body works its way through THE BODY IS A CONTAINER schema, as applied to the Mesopotamian textual record, in a thorough and theoretically sophisticated way. One of the main ideas of conceptual metaphor theory is that nonbodily domains can be used as models to conceptualize unseen processes within the human body, and THE BODY IS A CONTAINER is a straightforward first step in such a conceptualization. At the same time, however, it also seems that processes of fermentation were part of the conceptualization of transformation in Mesopotamia. No doubt, there is, hidden in among the container metaphors, a native model that used fluids (ranging from semen and alcohol to medicines in a liquid carrier) in more or less well sealed containers in order to represent internal states (Johnson 2017). Whether semen added to the womb, an alcoholic beverage introduced into the stomach, or a medical “potion” given to a patient, all of these procedures probably draw on a shared conceptual model.

In both Classical Sumerian mythology and a wide array of later incantations, the womb (in later texts, Sum. ša3.tur3 = Akk. šassūru, but in the Sumerian mythological texts, still simply ša3) always functions as the premier transformative environment. Yet as Steinert has emphasized, analogous transformational contexts from beer-making and metalworking were often used to describe processes of transformation – above all, the beer-making vat, the smelting oven, or the crucible of the metalworkers, and the human digestive tract or “stomach” (also denoted by ša3 in Sumerian). Each of these domains deserves a place in the early history of Mesopotamian conceptualizations of chemical reactions, but other than the womb, to which we have already referred, the beer-making vat played an especially powerful role in how Mesopotamians conceptualized the transformation of a series of raw materials into a new kind of substance. The fermentation process and the consequent creation of alcohol represented one of the most important (bio)chemical reactions in early Mesopotamian thought. The beer goddess Ninkasi is first attested in the earliest god lists in the mid-third millennium BCE, and The Ninkasi Hymn (first edited in Civil 1964, now re-edited in Sallaberger 2012) is one of our most important descriptions of a production process in Sumerian literature.

The Ninkasi Hymn 13–36

13.Your sourdough starter (lit. sprouted dough), formed with an enormous shovel,

transl. after Sallaberger 2012

14.The dough, with spices and honey mixed into the “well,”

15.O Ninkasi! Your sourdough starter, formed with an enormous shovel,

16.The sourdough, with spices and honey mixed into the “well,”

17.Your sourdough, baked in the huge oven,

18.It is smooth like the feel of hulled grain,

19.O Ninkasi! Your sourdough, baked in the huge oven,

20.It is smooth like the feel of hulled grain,

21.Your malt, covered with meal and with water poured in,

22.It is undulating vermin,

23.Ninkasi, your malt, covered with meal and with water poured in,

24.It is undulating vermin,

25.Your mash, with water added to the vessel,

26.It is the rising and sinking of waves.

27.Ninkasi, your mash, with water added to the vessel,

28.It is the rising and sinking of waves.

29.Your finished mash, spread out on huge reed mats,

30.The contents cooled (and) the … appeased,

31.Ninkasi, your finished mash, spread out on huge reed mats,

32.The contents cooled (and) the … appeased,

33.Your big (mass of) dried beer mash, ready to be formed,

34.Moistened with honey and wine,

35.Ninkasi, your big (mass of) dried beer mash, ready to be formed,

36.Moistened with honey and wine.

When Miguel Civil, undoubtedly one of the most important Assyriologists of the twentieth century, edited this text in 1964, more than fifty years ago, he could only arrive at a somewhat impressionistic description of what the hymn depicts: “the various steps of the brewing process … described in a poetic, but clearly recognizable, way” (1964: 67). Civil referenced “beer-making recipes” (viz. quantifications of ingredients and products, but not step-by-step processes), and one could easily infer from his edition that The Ninkasi Hymn is a poetic rendition of a beer-making recipe. In the half-century since then, two major advances have produced a far better interpretation of the text (and in doing so teach us something very important about how advances in understanding texts like this actually take place): Marten Stol produced a series of incredibly detailed studies of the realia involved in beer-making in the 1970s and 1980s (Stol 1971; Stol 1987–90), and more recently Zarnkow and coworkers were involved, as part of the excavations at Tell Bazi (northern Syria), in replicating the beer-making process in line with this and many other texts from early Mesopotamia (Zarnkow et al. 2006; Otto 2012).

These lines of research help us to see that The Ninkasi Hymn is not actually a recipe for producing beer, directly transmuted into a piece of Sumerian literature (thus quite different from an Akkadian parody like At the Cleaners); it is, instead, a hymnic description of the attributes of the goddess Ninkasi – what I have recently described as a type of ekphrastic description (Johnson 2019) – that lists each of the most important attributes of the goddess. Some of these attributes happen to correspond to steps in the production of sourdough, fermented mash, and a dried form of mash used for storage and long-distance journeys. The importance of these processes for our purposes here, however, is that they represent some of the most important metaphorical and symbolic meditations on chemical processes in all of Mesopotamian literature. The process can be summarized as the combination of an enzyme-rich “sourdough” (Sum. bappir = Akk. bappiru or pappiru), which takes the place of commercial yeast in modern recipes, with a sugar-rich mass of “malt” (Sum. munu4 = Akk. buqlu) and other grains. This yielded a “fermented mash” (Sum. sumun2 = narṭabu) that could be dried and stored in different ways (Sum. titab2 = Akk. titāpū, or Sum. dida = Akk. billatu). Crucially, the key metaphors for the chemical processes involved in the making of beer are the movement of masses of insects (“undulating vermin” in lines 22 and 24) and the movement of waves (“the rising and sinking of waves” in lines 26 and 28). This is depicting nothing other than the normal operation of the enzymes, yeasts, and bacterial action that take place in a sourdough starter. And this type of kitchen chemistry was undoubtedly at the very center of Mesopotamian conceptualizations of other, less accessible chemical processes.

Yet nowhere in The Ninkasi Hymn do we find the term that has taken on a seemingly crucial role in the secondary literature for Mesopotamian contexts of transformation, namely Sum. agarin3/4/5 = Akk. agarinnu. The danger with purely lexical studies is that they take the results of lexicographical study and generalize them into models of intellectual or cultural history. If, for example, we look at the entry for agarinnu in the standard Akkadian lexicon in English (CAD), we find three definitions: “beer mash,” “mother,” and “crucible”; it would be very easy to generalize agarinnu into a single term meant to cover all of the most important contexts of transformation in ancient Mesopotamia. If we make this term into a kind of symbolic representation for transformation in Mesopotamian thought, we are really imposing our own ideas on Mesopotamian society. As Sallaberger (2012) points out, the few lexical attestations of agarinnu take on a much clearer, if less dramatic, meaning in the context of the processes depicted in The Ninkasi Hymn. In the lexical list known as Hh XXIII, lines 1′–15′, the section moves from Sum. sa.hi.in.du “sourdough-yeast” through a number of different states or kinds of Sum. bappir “sourdough” and concludes with Sum. sumun2 “mash.” And it is near the start of this sequence that Sum. agarin4 = Akk. agarinnu occurs, so it is clear from this context that it refers to the sourdough starter (containing lactic acid bacteria and wild yeast) before it was mixed into a new sourdough. Its extension to metalworking (Sum. urudaagarin3 = Akk. agarinnu in Diri IV 83), though with a distinct spelling and not used outside of lexical lists, is already found in the Old Babylonian period. The orthography of Sum. agarin4, conventionally AMA.ŠIM but identical to AMA.BAPPIR2, suggests that it was etymologized as the “source of the sourdough,” with Akk. ummu (= Sum. ama) in one of its perfectly regular senses (“source, origin”) rather than a complex metaphor involving “mother” and hence “womb” (see generally Steinert 2017: 300).

Greco-Roman World

By Dr. Matteo Martelli

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

Hephaestus (or Vulcan in Latin mythology) was the god of metalworking, a smith himself, expert in the working of a variety of metals, such as gold, silver, bronze, and iron. His house and workshop are described in the Iliad, when Thetis visits the smith god and asks him to forge new weapons for her son, Achilles (Il. XVIII 368–81; see Figure 5). Hephaestus’ house was bright as a star and had been built in bronze by the god himself. He was also believed to have erected the houses of the gods, temples, and the palace of Alcinous, which had metallic walls and a bronze threshold:

The brilliance over the high-roofed house of great-hearted Alkinoos / was like that of the sun or moon. There were bronze walls / that extended on both sides of the threshold into the interior, / and the topmost row of stones was made of lapis-lazuli (kyanos).

Odyssey, VII 84–7; transl. by Powell 2014

After deciding to grant Thetis’ wish, Hephaestus got down to work, and produced the famous shield of Achilles (Il. XVIII 470–608). Twenty self-moving bellows fed the fire below the crucibles, and Hephaestus put various metals on the fire. He worked bronze (or copper; chalkos in Greek), tin, precious gold, and silver on a great anvil, handling a heavy hammer with one hand, the tongs with the other. The metals were used to forge five different layers of the shield, as well as many details of the rich imagery that decorated it. The semiprecious blue stone kyanos was also added to enrich the decoration. Hephaestus creates a scene of a vineyard full of large golden grapes, marked off by a dark blue trench (i.e. made of kyanos), and a fence of tin (Il. XVIII 564–5; for a recent and up-to-date discussion of the technology depicted in Iliad XVIII, see D’Acunto 2009).

As pointed out by Acton (2014: 7), since the preclassical period, craftsmen were well regarded in ancient societies, and their images in bronze and on vase paintings were common until at least the fifth century BCE. Some patterns may be identified in the way manual workers were represented: they usually have short hair, sometimes with bands or wreaths on their head; adult craftsmen usually have beards, while young workers appear beardless. Baldness has been interpreted either as a sign of old age or as an indication of coarseness. Bald bronze workers with long or snub noses, sunken jaws, and swollen lips, such as those depicted in a two-handled jar (pelikē) of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (inv. 13100; 440–430 BCE) or in a lekythos of the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence (inv. 25109; 470–460 BCE), might seem to be caricatured figures (Chatzidimitriou 2014: 79–81). Indeed, a certain humor against workers has been detected in a stamnos (a type of jar) of the Metropolitan Museum in New York (inv. 17.230.37; 460–450 BCE), which depicts a carpenter who turns away from a rich woman; a slave between the two figures turns her face toward the mistress while pinching her nose, presumably because of the bad smell of the worker (Mitchell 2009: 70–1). On the other hand, bald old craftsmen were certainly more experienced, and sometimes baldness could simply mark workmen who had properly mastered their art (Birchler Emery 2008).

In vase paintings, craftsmen often wear a himation, a loose tunic that is either wrapped around their bodies, especially when they are seated, or tied around their waists when they are depicted working while standing. Along with semidraped workers, naked craftsmen are quite common, as recently pointed out by Roger Ulrich:

The Attic potter showed many of his subjects at work firing pottery, mining, woodworking, blacksmithing and plowing wearing nothing at all. … It has been recognized that Greek athletes commonly exercised while nude, but one must wonder about the comfort and safety of working without any protective clothing.

Ulrich 2008: 56

If nudity may have been part of the artistic convention, blacksmiths and potters in particular, even when represented unclad, often wear a leather pilos (“skullcap”; see Figure 6), which was expected to protect artisans who work next to furnaces (Chatzidimitriou 2014: 65–71). Moreover, tools and instruments often accompany the depicted scenes (Ulrich 2008).

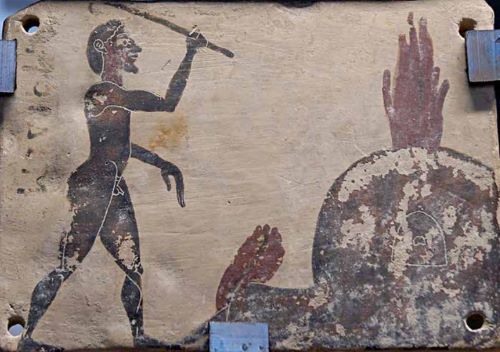

For instance, a series of eight painted votive plaques found in the sanctuary of Poseidon at Penteskouphia (in the proximity of Corinth; sixth century BCE) display naked male potters next to kilns used for the firing process (see Figure 7; Hasaki 2019). In many plaques, beehive-shaped kilns stand at the center of the depicted scenes; they are usually slightly taller than the craftsmen, with the vent hole at the top and the loading door for inserting or removing the pottery depicted at the side. In only one case (Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. 802b), a ladder is necessary to reach the top of a kiln.

In some cases, ancient vases also feature gods and women at work. In scenes of weaving or spinning, women usually wear the peplos (a long garment with a broad overfold) or chiton (a sleeveless, rectangular garment); the same iconography appears in the Caputi hydria of the Torno collection in Milan (fifth century BCE), which depicts a woman decorating the handles of a volute-krater (i.e. a large vessel used to dilute wine with handles that curl in a volute). Hephaestus, on the other hand, is depicted in the interior scene (tondo) of the famous Berlin Foundry Cup (early fifth century BCE), a red-figure kylix (a wide-bowled drinking cup) kept at the Altes Museum in Berlin (see Figure 5); Thetis is standing in front of a bearded Hephaestus, who is seated on a stool cushioned with a fine pillow; he wears a loose tunic, according to the pattern that we have discussed above. The god holds a heavy hammer in one hand and Achilles’ helmet in the other, while a hammer and an anvil are depicted behind the goddess Thetis. The scene continues in the exterior part, where we find one of the most detailed pictures of a bronze workshop from antiquity: a bearded male figure stokes coals in a furnace, while in the back a second young worker manipulates bellows to kindle the fire. Other craftsmen work to finish a statue, and various tools (hammers, a saw), along with various parts of statues (heads, feet, and hands), are depicted in the background (Mattusch 1980; see Figure 6).

In addition to potters and bronze-workers, other professions were also represented. For instance, three perfumers seated in an Athenian perfume shop are depicted in a lekythos (oil flask; late sixth century BCE) held by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (inv. 99.526). Oil flasks were the most common containers for perfumes and cosmetics in antiquity. The Boston black-figure vessel features three red-bearded men wearing elegant mantles and seated on sophisticated stools with animal legs. The man at the left holds a flower in his hand, perhaps one of the ingredients used to prepare the perfumes that were sold; the man at the center of the scene holds a siphon, probably used to permit the customers to taste the scented oils. On the other hand, a pelikē (a wine container; 520–490 BCE) kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence (inv. 72732) displays an old bald oil merchant who calls to a mantled woman and, at the same time, uses a stick to pick some oil (or wine) from an amphora in front of him: the painter recorded the words of the merchant, who takes hold of the woman’s arm and says, “It is good!” The woman, however, eloquently pinches her nose (Mitchel 2009: 70–1).

As for the professional figures in the drug business, who are referred to with a variety of terms in ancient sources (root-cutters, root-sellers, drug-dealers, or perfume-makers), literary and scientific texts provide us with a more ambiguous representation. Scholars have often emphasized how these figures had a poor reputation in antiquity, at least according to the pictures depicted in medical sources (Boudon-Millot 2003; Samama 2006). After all, there was a certain degree of competition with the physicians, who also used pharmaka to cure their patients. As Laurence Totelin (2016b: 72–3) points out, drug-sellers knew about more than just plants, poisons, and aphrodisiacs; they also dealt with spiders and snakes. Aristotle, for instance, after observing the specimens of snakes and spiders kept alive in the shops of drug-sellers, infers that these animals can live for a long time even without food (Hist. An. VIII 4, 594a20–4). Aristotle also refers to the weak bites of the snakes of the druggists (Hist. An. IX 39, 622b34), who, in some cases, might have let themselves be bitten by harmless spiders in order to show the efficacy of the pharmaka they sold to their customers.

As for perfume-makers, Galen’s representation is somewhat ambivalent. In some cases, he praises their expertise in the preparation of medicines; on the contrary, in a passage of his treatise On the Capacities of Simple Drugs (II 27 = XI 537 Kühn), he criticizes their method for making rose oil (rhodinon); perfume-makers, in fact, tended to adulterate its composition by adding ingredients that could strengthen the scent of the oil. On the other hand, Galen includes medicinal recipes taken from drug-sellers and root-cutters in his treatises on the composition of drugs and antidotes for poisons (Guardasole 2006), and Latin inscriptions found in Brescia (CIL V 4489, second to third centuries ce) preserve a record of the wealthy college of the pharmacopolae who were also in charge of estates (Totelin 2016b: 78, 85).

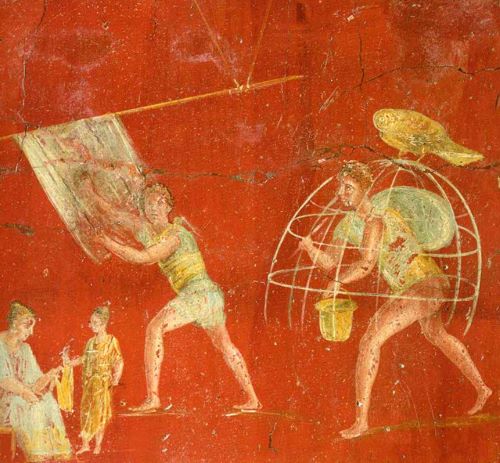

A certain opposition between otium (“leisure”) and negotium (“daily business”) is certainly evident in the work of Roman philosophers, such as the Stoic Seneca (first century CE). In Epistle 90, for instance, he criticized the earlier philosopher Posidonius, who attributed the invention of important technologies to ancient philosophers. Seneca contrasts wise philosophers, who must train their minds more than their hands, with industrious artisans, but other sources show the value that Roman craftsmen attributed to their own art. Roman reliefs on gravestones, in fact, often display craftsmen alone represented along with a few tools of their art. Likewise, many frescos discovered in Pompeii depict craftsmen or, in some cases, cupids who practice different arts. In the famous House of the Vettii, a room was decorated by thirteen panels depicting cupids and psyches at both work and play (62–79 CE). Ten of these panels remain, and three of them deal with arts. In one fresco, various cupids are depicted as perfume-makers extracting flagrances from flowers and stirring the scented oil in a cauldron. In another fresco, goldsmith cupids are depicted: a cupid works on a gold bowl at the right, a psyche melts the metal, while various objects for sale are depicted at the center of the scene. Finally, a third fresco depicts cupids at work in a cloth-treating shop or fullery (Clarke 2003: 100–5).

Scholars usually agree that fullers suffered from a poor reputation, probably due to the dirty nature of their work. While literary texts such as those of Roman historians and comic dramas (see Flohr 2013a: 324–8) seem to support this view, other sources, in particular various paintings in fullonicae excavated in Pompeii, seem to provide a different picture. For instance, fullonica VI 8.20 is decorated by four frescos that represent fullers at work (see Figure 8.8). As stressed by Clarke (2003: 117), the owner of the building, who certainly commissioned the frescos, “wanted to show his pride not only in his establishment but also in his workers. If he instructed the painters to make into portraits the vignettes of the workers … – as I believe he did – then he wanted to show not just what his employees did but also what they looked like.”

The crafts were not only represented in reliefs and paintings – they were also praised by ancient scientists and physicians. In his Exhortation to Study the Arts (Protrepticus), Galen contrasts those who trust blind Fortune to those who cultivate their rational soul through the practice of the crafts (technai). Hermes is the patron of the second group, which is portrayed by Galen as a band marching in three circles (Protr. 5.1 = I 7 Kühn). Geometers, mathematicians, philosophers, doctors, and astronomers march closest to the god; painters, sculptors, carpenters, and experts in all the crafts are included in the other two bands. On the contrary, those who neglect to learn a craft (technē) are blind followers of the daimon Tychē (“Fortune”); unable to develop professional skills in any particular craft, they entrust themselves to the unpredictable Fate for their success. Indeed, learning a craft could be difficult and time-consuming, and the easier path of Tychē could have tempted ancient craftsmen. Like Galen, the Greco-Egyptian alchemist Zosimos of Panopolis adopted a firmly critical stance against those who preferred to trust fortune rather than committing themselves to a study of the fundamental writings of the alchemical art. In his work On the Letter Omega (Authentic Memoires, I in Mertens 1995: 1–10), Zosimos directs a vitriolic attack against those alchemists who did not recognize the value of On Furnaces, an alchemical book ascribed to Maria the Jewess. In particular, those who, without being trained, are fortunate and succeed in dyeing techniques dismiss the teachings of On Furnaces as false or unnecessary and heap ridicule on the book. However, when their success comes to end, they reluctantly confess that there was some truth in the book. They are, in fact, escorts of Fate in its procession.

The Egyptian priest Neilos clearly exemplifies this attitude. In the chapter On the Treatment of the Body of Magnēsia (CAAG II 188–91), Zosimos fiercely criticizes Neilos and his entourage, who gave foolish and vain instructions about alchemical tinctures. Seeking false methods for obtaining gold, they did not base their practice on a solid theoretical foundation and, for this reason, easily made fools of themselves. This becomes evident at the end of the chapter, when Zosimos depicts the priest Neilos as a ridiculous novice. It is worth quoting the passage in full, since it provides us with one of the rare descriptions of an alchemist at work in Greco-Roman Egypt:

For instance, once your priest Neilos provoked laughter, when he roasted molybdochalkos in a baking-oven: so that, if one adds some “bread” [i.e. slabs of magnēsia], he ends up kindling [the fire] with kōbathia [arsenic ores] all day long. Blind in his bodily eyes, he did not understand the failure he was doomed to, but he even puffed up with conceit, and he collected and showed the ashes, after they cooled down. When he was asked “where is the whitening?,” he was at a loss and answered that it went deep into [the ashes]. Then he added copper, dyed its dross: in fact, there was nothing solid [to be dyed]. Then, he desisted and went away; and he fled deep into [those ashes], under which the same whitening of the magnēsia went. … Pass my greetings to Neilos, the “kōbathia-burner”.

CAAG II 191

In this passage, Zosimos plays with the alchemical concept of “deep tincture,” according to which the dyeing substances must sink into the metal in order to produce its complete transformation. On the contrary, Neilos’ procedure does not bring about any transformation; the whitening penetrated so deeply, Zosimos says ironically, that it was not visible at all. From a technical point of view, Zosimos stresses that Neilos used a klibanos (Lat. clibanus), a portable oven used to bake bread, to make magnēsia white. Even though the klibanos could probably serve different purposes – it is, indeed, mentioned in pharmacological and alchemical texts as a tool for roasting a variety of ingredients (e.g. CAAG II 289, 346, 369, 391) – it is difficult to escape the impression that Zosimos disapproved of Neilos’ alchemical experiment, which is presented as an extemporaneous performance. His approach to alchemical practice was as shallow and superficial as that of his followers. They were too self-confident and arrogant to listen to more skilled and experienced alchemists and, we can infer, to waste time reading the writings of the ancients – such as the treatise On Furnaces that Zosimos discusses in On the Letter Omega. Being more interested in making gold than in theories (CAAG II 190,20–1), these alchemists dared to prepare alchemical tinctures rashly and without understanding.

The tension between learned alchemists and untrained practitioners who approached alchemy with the sole purpose of making money (often by cheating their clients) is also evident in the few nonalchemical sources that deal with this craft in late antiquity. On the one hand, in his dialogue Theophrastus, the Neoplatonic philosopher Aeneas of Gaza (d. ca. 518 CE) claims that alchemists are able to turn matter into a superior state, as they do when transmuting metals into excellent gold or when making brilliant glass (Colonna 1958: 62–3; see Beretta 2009: 108–9). On the other hand, the Byzantine chronicler Malalas (sixth century ce) has preserved the following record of the misfortunes of an alchemist (actually a trickster) from Antioch, who tried to cheat the Byzantine emperor Anastasios I (reigned 491–518 CE; Chronicle, XVI 395 Dindorf):

During [Anastasios’] reign a man named John Isthmeos, who came from the city of Amida, appeared in Antioch the Great. He was an alchemist and a tremendous imposter. He secretly went to the money dealers and showed them some hands and feet of statues made of gold, and also other figurines, saying that he had found a hoard of such figurines of pure gold. And so he tricked many of them and conned them out of a lot of money. The Antiochenes nicknamed him Bagoulas, which means a slick imposter. He slipped through everyone’s fingers and fled to Constantinople, and there too he conned many money dealers and so came to the emperor’s attention. When he was arrested and brought before the emperor, he offered him a horse’s bridle of solid gold with the nose-piece inlaid with pearls. The emperor Anastasios took it, saying to him, “He you will not con,” and banished him to Petra, where he died.

transl. by Jeffrey et al. 1986: 222

Conclusions

By Dr. Marco Beretta

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

Ancient representations of the chemical arts are both varied and numerous. In Egypt, craftsmen were richly represented in paintings, low-relief carvings, and in groups of small statuettes. However, these iconographic reconstructions did not play a didactic role and their main aim was to transmit the memory of their works. The most important achievements of the chemical arts were covered by secrecy and therefore their visual representations carefully avoided too detailed descriptions of the techniques involved. Despite the lack of technical details, Egyptian tombs offer rich iconographic views on beer- and wine-making, on metallurgical craftsmanship, on the different phases for the preparation of perfumes, and on other arts. In contrast to the richly imaginative world of the Egyptians, in Mesopotamia there were only few iconographic descriptions of the chemical arts, and none of them related directly to the technical processes. However, Mesopotamian texts introduced powerful metaphors such as that of the oven representing the womb that effectively described unseen domains within the body. Chemical processes too, such as a recipe for making beer, alluded to a description of the attributes of a goddess. The use of this kind of metaphor indicates the cultural importance achieved by the chemical arts and instruments.

Hephaestus, the Roman Vulcan, was depicted in his forge in Homer’s Iliad, and this image became an exceedingly successful way to depict metallurgy within mythological contexts. However, both Greeks and Romans extensively represented craftsmen – with images and in words – that evoked the real workshops in which they operated. The frescos surviving in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii offer a vivid series of scenes of chemical workshops that are enriched with detailed descriptions of operations and instruments. At this time (79 CE), the chemical arts acquired an autonomous role in Roman society and culture.

See bibliography at source.

Chapter 8 (211-235) from A Cultural History of Chemistry in Antiquity, edited by Marco Beretta (Bloomsbury Academic, 05.19.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.