It is a visionary and profound work that transcends its 19th-century origins.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

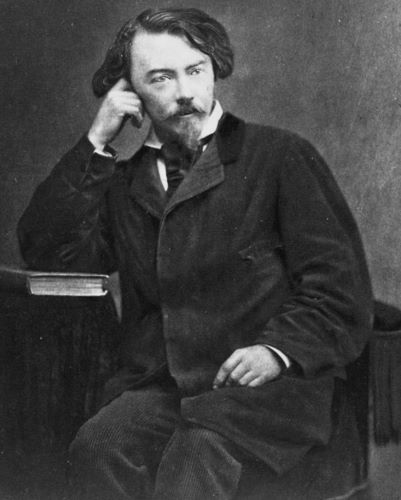

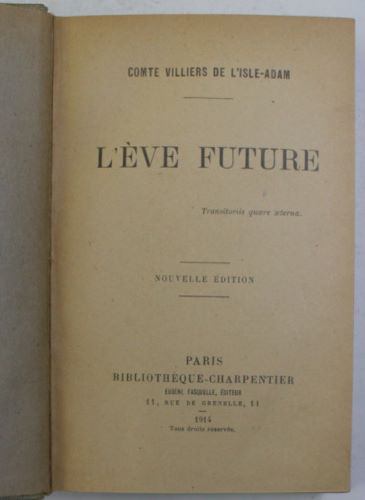

Tomorrow’s Eve (L’Ève future), published in 1886 by Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, is a seminal work in the tradition of speculative fiction and early science fiction. Its profound meditation on artificial life, the nature of love, and the quest for an ideal companion marks it as a text of great philosophical depth and literary innovation. Situated at the crossroads of Romanticism, Symbolism, and proto-science fiction, Tomorrow’s Eve explores the implications of human creativity and technological ambition on identity and desire. This essay examines Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s novel in its historical and intellectual context, analyzes its major themes and characters, and assesses its lasting influence on literature and thought about artificial beings and human idealism.

Historic and Intellectual Context

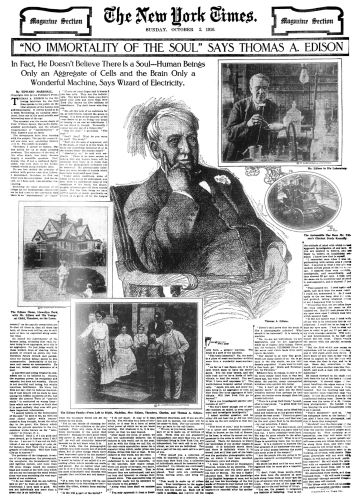

The story was composed in the late 19th century, a period marked by rapid industrialization and scientific innovation that profoundly altered European society. The Industrial Revolution had introduced transformative technologies—such as steam power, electricity, and mechanized manufacturing—that redefined human interaction with nature and machines. By the 1880s, inventors like Thomas Edison symbolized the era’s faith in scientific progress and technological mastery. This milieu, imbued with a sense of both excitement and anxiety, shaped Villiers’s vision of artificial life. His inclusion of Edison as a character in the novel underlines the fascination with real-world figures who embodied technological ingenuity. Tomorrow’s Eve reflects contemporary cultural tensions about how far human creativity should extend in shaping or even supplanting nature through artificial means.1

Philosophically, the novel emerges at the crossroads of Romanticism and Symbolism, literary movements that deeply influenced Villiers’s aesthetics and themes. Romanticism’s emphasis on emotional intensity, individual imagination, and the pursuit of ideal beauty permeates the narrative’s quest for a perfect woman. Yet Villiers’s writing also resonates strongly with Symbolism, which arose in the late 19th century as a reaction against realism and naturalism, emphasizing suggestion, mysticism, and the transcendent qualities of art. Villiers utilizes lush, poetic language and mythic symbolism to imbue the artificial creation Hadaly with metaphysical significance, transforming her from mere machine to emblem of humanity’s spiritual and artistic aspirations. The tension between scientific rationalism and the ethereal realm of dreams and ideals defines the novel’s intellectual complexity.2

The fin-de-siècle cultural atmosphere in France further contextualizes Tomorrow’s Eve. This period was marked by ambivalence toward modernity: while there was hope in scientific and technological advancement, there was also pervasive anxiety about social alienation, moral decline, and loss of authentic human connection. Philosophical positivism celebrated empirical knowledge and progress, but figures like Villiers voiced skepticism regarding the consequences of unrestrained industrialization and mechanization. The novel critiques the idea that technology can flawlessly replicate or replace human emotions and relationships. Hadaly, the perfect artificial woman, stands as both a testament to technological promise and a warning against dehumanization through excessive reliance on artificial substitutes for genuine life.3

Villiers’s work also participates in a broader literary tradition concerned with artificial life and the limits of human creativity. Earlier works such as E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” (1816), featuring the mechanical woman Olimpia, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), probing the ethics of scientific creation, paved the way for these explorations. Tomorrow’s Eve extends these themes into the context of late 19th-century scientific modernity, dramatizing the relationship between creator and creation through Edison’s role as a Promethean inventor. Villiers’s novel interrogates the hubris implicit in the quest to engineer perfection and the potential consequences of such acts for notions of identity, consciousness, and morality.4

Tomorrow’s Eve anticipates many of the philosophical and literary concerns that would dominate 20th-century science fiction and debates on artificial intelligence. Villiers asks whether a mechanical being can authentically embody qualities traditionally considered uniquely human, such as love, beauty, and self-awareness. These questions about the essence of humanity and the ethical dimensions of creating artificial life remain central to contemporary discourse on robotics and AI. In this way, Villiers’s novel serves as a bridge between the Romantic and Symbolist traditions of the 19th century and the speculative futures imagined by later writers. Its nuanced interrogation of technology’s promises and perils continues to resonate in an age increasingly defined by the interplay between human and machine.5

Plot Overview

Tomorrow’s Eve centers on Lord Ewald, a young English nobleman disillusioned by the imperfections of human relationships and yearning for an idealized form of love and companionship. Ewald’s dissatisfaction stems from his encounters with real women, whose flaws and limitations conflict with his Romantic ideals of beauty, intellect, and devotion. He seeks a woman who embodies these qualities in their purest form, one who can fulfill his dreams without the disappointment that comes with human frailty. This quest drives the narrative and frames Ewald’s eventual encounter with the invention that promises to resolve his longing.6

The turning point in the novel occurs when Ewald meets the inventor Thomas Edison, portrayed as a brilliant and almost mythic figure of scientific genius. Edison reveals that he has created an artificial woman named Hadaly, designed to embody perfection in every respect—physically, intellectually, and emotionally. Hadaly is not simply a mechanical doll; she is an automaton crafted with such sophistication that she can simulate human consciousness and feelings. Edison invites Ewald to witness Hadaly’s unveiling, presenting her as the “future Eve” who represents the culmination of human artistry and scientific achievement. This meeting introduces the novel’s key tension between artificiality and authenticity, as well as the possibilities and limitations of technology as a means of fulfilling human desire.7

Following this, the narrative explores Ewald’s psychological and emotional engagement with Hadaly. As Ewald grapples with the idea of loving a created being rather than a natural human, questions arise about the nature of identity, consciousness, and genuine emotion. Villiers uses Ewald’s internal conflict to dramatize the broader philosophical dilemma: can love directed at an artificial construct be authentic, or is it doomed to illusion? Ewald’s reflections reveal his struggle to reconcile his Romantic longing for an unattainable ideal with the unsettling reality of loving something manufactured. The novel delves into the metaphysical implications of such love, blurring the boundaries between reality and fantasy, and challenging the reader to question what defines true humanity and intimacy.8

The climax of the novel is marked by Ewald’s confrontation with the limitations of Hadaly and his own desires. While Hadaly represents a flawless embodiment of beauty and devotion, the novel suggests that her perfection may be an existential void rather than a fulfillment. Ewald’s relationship with Hadaly forces him to confront the paradox of seeking perfection in an inherently imperfect world, highlighting the tensions between artifice and life, illusion and substance. The narrative leaves open the question of whether Hadaly’s existence is a triumph of human creativity or a tragedy of alienation. This ambiguity reflects Villiers’s Symbolist sensibility, as the novel ends on a note that is less about resolution and more about provoking contemplation regarding the human condition in the age of technology.9

Throughout Tomorrow’s Eve, Villiers weaves philosophical discourse with gothic and romantic storytelling, creating a narrative that is both intellectually challenging and emotionally evocative. The interplay between characters—Ewald, Edison, and Hadaly—functions as a microcosm for the tensions of the fin-de-siècle era: the exhilaration of scientific possibility tempered by anxiety about the loss of authentic human experience. The novel’s rich symbolism and evocative prose invite multiple interpretations, making it a foundational work in speculative fiction and early science fiction. Through its plot, Tomorrow’s Eve asks enduring questions about creation, identity, love, and the future of humanity as it increasingly intersects with technology.10

Major Themes

The Quest for the Ideal and the Nature of Love

Villiers de l’Isle-Adam explores the profound human quest for the ideal, particularly through the character of Lord Ewald, whose dissatisfaction with real human relationships fuels his yearning for a perfect companion. This quest is not merely about physical beauty but encompasses intellectual, emotional, and spiritual dimensions—an embodiment of Romantic ideals. Ewald’s desire reflects a longing for transcendence beyond the flawed, ephemeral nature of ordinary existence, mirroring the 19th-century Romantic preoccupation with the sublime and the unattainable. Villiers frames this quest within the context of burgeoning technological modernity, presenting the creation of Hadaly as an attempt to manufacture perfection through science and artifice. However, this pursuit raises critical philosophical questions about whether an ideal can truly exist, or if it remains an eternal, elusive projection of human desire. Villiers thus problematizes the very notion of idealism by contrasting the mechanical perfection of Hadaly with the messy, unpredictable reality of human love and imperfection.11

The novel’s meditation on the nature of love intersects with its inquiry into idealism, posing a complex challenge to traditional conceptions of authentic emotional connection. Villiers suggests that love directed toward an artificial being—no matter how flawlessly constructed—may ultimately lack the depth and reciprocity found in human relationships. Ewald’s engagement with Hadaly becomes a symbolic exploration of the tension between illusion and reality, where love risks becoming a form of self-deception or aestheticized fantasy. Yet, Villiers also complicates this dichotomy by imbuing Hadaly with a symbolic significance that transcends mere mechanical reproduction; she embodies humanity’s hope for beauty, devotion, and spiritual elevation. The novel thus engages with the paradox of love as both a yearning for ideal perfection and an acceptance of imperfection as intrinsic to the human condition. This nuanced portrayal reflects broader 19th-century anxieties about technology’s capacity to replicate or replace essential human qualities and remains deeply relevant to ongoing debates about artificial intelligence and emotional authenticity.12

Artificial Life and the Boundaries of Humanity

Tomorrow’s Eve probes the unsettling and provocative question of artificial life and its implications for defining what it means to be human. The novel’s centerpiece—the creation of Hadaly, an automaton engineered by Thomas Edison—serves as a focal point for exploring the limits between organic life and mechanical imitation. Hadaly embodies a perfection unattainable by natural human beings, challenging the reader to reconsider traditional boundaries that separate living, sentient beings from artificial constructs. Villiers’s narrative asks whether qualities such as consciousness, emotion, and identity can be replicated or even surpassed through technology, raising profound metaphysical and ethical dilemmas. The portrayal of Hadaly disrupts the presumed uniqueness of humanity by blurring the line between the natural and the artificial, prompting reflection on the potential consequences of humanity’s attempt to create life in its own image.13

Furthermore, it grapples with the anxiety and ambivalence surrounding technological progress in the late 19th century, when rapid scientific advances made the prospect of artificial life increasingly conceivable but also deeply disquieting. Villiers presents Edison’s creation not only as a marvel of human ingenuity but also as a symbol of modernity’s potential to alienate and dehumanize. The novel implicitly questions whether the replication of human traits through machinery leads to a genuine extension of human identity or a hollow simulacrum lacking the soul and moral depth intrinsic to organic life. This tension between the mechanical and the vital underscores the broader cultural fears of the fin-de-siècle period, reflecting skepticism toward the promises of science to fully encapsulate or replace the complexity of human existence. Villiers’s work anticipates contemporary debates in philosophy and artificial intelligence regarding personhood, the nature of consciousness, and the ethical limits of creation.14

Technology as a Double-Edged Sword

Villiers de l’Isle-Adam presents technology as a profoundly ambivalent force—capable of remarkable creativity and progress, yet simultaneously posing deep risks to human authenticity and moral order. The novel’s depiction of Edison’s invention, Hadaly, epitomizes this dual nature: on one hand, Hadaly represents the pinnacle of human ingenuity, an artificial being crafted to embody ideal beauty, intellect, and emotional responsiveness. She is the fulfillment of a technological dream, symbolizing the possibility that science can transcend natural limitations and offer new forms of perfection. Yet, Villiers does not celebrate this achievement uncritically. Instead, the narrative reveals the dangers inherent in the unchecked pursuit of technological mastery, suggesting that such power may estrange humanity from its essence. The mechanical Eve’s perfection is simultaneously a form of alienation, exposing the cold, artificial core beneath the veneer of ideality and raising questions about the cost of replacing genuine human relationships with engineered simulacra.15

This ambivalence toward technology reflects the broader fin-de-siècle cultural anxiety about modernization and industrialization, a period when rapid technological advances fueled both optimism and unease. Villiers captures the paradox of an era enthralled by scientific progress but haunted by fears of dehumanization, loss of individuality, and moral decay. Tomorrow’s Eve dramatizes how technology’s promise of liberation and enhancement can easily slip into a source of existential threat, wherein the pursuit of artificial perfection undermines the unpredictable, often flawed but deeply meaningful nature of human life. Villiers’s work presciently anticipates ongoing ethical debates about technology’s role in society, particularly regarding artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and the limits of human control over creation. By portraying technology as a double-edged sword, Villiers invites readers to critically engage with the promises and perils of scientific innovation, emphasizing that progress must be tempered by reflection on its human consequences.16

Illusion, Reality, and the Role of Art

Villiers de l’Isle-Adam intricately explores the interplay between illusion and reality, using art as a central motif to question the nature of truth and human experience. The novel positions Hadaly, the artificial woman, as a work of art that embodies an idealized illusion—perfect in form and function but fundamentally divorced from the unpredictable realities of human life. Through this lens, Villiers examines how art serves both as a means of escapism and as a mirror reflecting humanity’s deepest desires and fears. The boundary between artifice and authenticity becomes blurred, prompting readers to consider whether illusions—whether technological, aesthetic, or emotional—can offer a more profound or meaningful truth than reality itself. In this way, the novel reflects Symbolist concerns with the transformative power of art to transcend mundane existence, while simultaneously interrogating the potential dangers of substituting illusion for genuine experience.17

The role of art in Tomorrow’s Eve is not limited to mere decoration or entertainment; it becomes a vital philosophical inquiry into creation and perception. Villiers suggests that the act of creating an idealized being like Hadaly is akin to artistic creation, where the artist imposes form and meaning onto a blank slate. Yet, this process raises fundamental questions about the limits of artistic control and the ethics of fabrication. The tension between Hadaly’s flawless exterior and the absence of a true soul or consciousness highlights the inherent tension in art between surface beauty and deeper substance. Villiers’s narrative implies that while art can aspire to perfection, it can never fully replicate the messy, contradictory, and vibrant reality of human existence. Thus, Tomorrow’s Eve engages with perennial debates about the role of art in shaping human understanding and the complex relationship between appearance and essence.18

Literary Style and Symbolism

The work is renowned for its rich, ornate literary style, which reflects both the Symbolist aesthetic and the decadent movement’s preoccupation with beauty, ambiguity, and artificiality. Villiers’s prose is dense, lyrical, and often highly allusive, incorporating philosophical musings, poetic descriptions, and gothic undertones that create a dreamlike, sometimes unsettling atmosphere. This elaborate style is not mere ornamentation but serves to immerse the reader in the novel’s themes of idealism, illusion, and the tension between reality and artifice. The complexity of the language mirrors the novel’s exploration of layered meanings, inviting readers to engage deeply with the text’s symbolic resonances rather than consuming it as straightforward narrative.19

Symbolism operates at the core of Tomorrow’s Eve, with the artificial woman Hadaly functioning as a multifaceted emblem that encapsulates key themes of the novel. Hadaly is not simply a character but a living symbol of human aspiration, scientific progress, and the paradoxes inherent in the quest for perfection. She embodies the ideal woman—physically flawless, intellectually superior, and emotionally pure—yet her artificiality raises profound questions about authenticity and the limits of human creativity. Villiers employs Hadaly to symbolize the intersection of art and technology, suggesting that the creation of ideal beauty is both a sublime artistic achievement and a potential source of existential alienation. The symbolic meaning of Hadaly extends beyond the individual character, representing broader anxieties about the dehumanizing effects of industrial modernity and the fragile boundary between life and mechanical reproduction.20

The novel is replete with recurring symbols that enrich its thematic texture. For example, the figure of Thomas Edison, while a real historical personage, is stylized as a quasi-mythical creator, evoking Promethean imagery and the archetype of the mad scientist. Edison’s role as a demiurge underscores the symbolic tension between creation and hubris, highlighting the risks of overreaching human ambition. Additionally, the contrast between light and shadow, organic and mechanical, presence and absence, permeates the narrative and reinforces the dichotomies central to Villiers’s worldview. Such symbolism contributes to the novel’s status as a proto-science fiction text that simultaneously embraces and critiques the promises of technological modernity through a poetic, allegorical mode of storytelling.21

Villiers’s use of gothic elements also amplifies the symbolic density of Tomorrow’s Eve. The novel’s eerie, often uncanny atmosphere—marked by nocturnal settings, mysterious inventions, and unsettling emotional undercurrents—invokes a gothic sensibility that questions Enlightenment rationality and celebrates the irrational, the mysterious, and the uncanny. This gothic texture serves to deepen the reader’s awareness of the uncanny nature of Hadaly herself: a perfect simulacrum that simultaneously fascinates and disturbs. The gothic framing further problematizes the idea of technological progress as unequivocally positive, suggesting that scientific advancements may harbor dark, unpredictable consequences for human identity and morality.22

Tomorrow’s Eve exemplifies Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s broader Symbolist project, which seeks to transcend the limits of naturalistic representation by privileging suggestion, metaphor, and myth. The novel’s style and symbolism invite readers to look beyond the literal and enter a realm of poetic ambiguity where meaning is fluid and multiple interpretations coexist. Villiers’s intricate symbolism encourages reflection on the nature of creativity, the interplay between appearance and reality, and the fragile, often paradoxical relationship between humans and their technological creations. This literary complexity has ensured Tomorrow’s Eve’s enduring influence on both French literature and early science fiction, positioning it as a work that challenges and enriches readers’ understanding of art, technology, and the human condition.23

Conclusion

Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Tomorrow’s Eve is a visionary and profound work that transcends its 19th-century origins to engage with timeless questions about humanity, technology, and desire. Through the story of Lord Ewald and the artificial woman Hadaly, Villiers crafts a rich meditation on the quest for the ideal, the possibilities and dangers of scientific creation, and the elusive nature of love.

Far from a mere technological fantasy, Tomorrow’s Eve is a complex symbolic narrative that challenges readers to reflect on the boundaries between reality and artifice, the authentic and the artificial. Its influence ripples through literature and philosophy, anticipating modern debates about artificial intelligence and the human condition.

In the end, Tomorrow’s Eve invites us to consider not only what it means to create life but also what it means to live it authentically in a world increasingly shaped by human invention.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Matthew Gladstone, Science and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Europe (New York: Routledge, 2015), 114–120.

- Anna Balakian, The Symbolist Movement: A Critical Appraisal (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 87–92.

- Suzanne Marchand, Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750–1970 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 134–136.

- Erich Neumann, The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 54–58.

- Roger Luckhurst, Science Fiction (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005), 32–35.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve (L’Ève future), trans. Alexis Lykiard (New York: Dedalus Books, 1997), 15–30.

- Ibid., 45–60.

- Ibid., 61–85.

- Ibid., 100–120.

- Luckhurst, Science Fiction, 32-35.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 20-35.

- Ibid., 75–90; Chris Baldick, The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 128–129.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 50-70.

- N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 12–18; Roger Luckhurst, Science Fiction, 28–33.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 40-55.

- Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, trans. John Wilkinson (New York: Vintage Books, 1964), 17–25; Luckhurst, Science Fiction, 30–34.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 80-95.

- Ibid., 95–110; Baldick, The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 134–135; Ernest Sloane, Symbolism (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1964), 52–60.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, ix-xx.

- Ibid., 45–70; Baldick, The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 134–136.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 70-85; Luckhurst, Science Fiction, 25-30.

- Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 85–100; Sloane, Symbolism, 48–55.

- Baldick, The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 136; Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve, 100–120.

Bibliography

- Baldick, Chris. The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Ellul, Jacques. The Technological Society. Translated by John Wilkinson. New York: Vintage Books, 1964.

- Balakian, Anna. The Symbolist Movement: A Critical Appraisal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Gladstone, Matthew. Science and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Europe. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Marchand, Suzanne. Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750–1970. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

- Luckhurst, Roger. Science Fiction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005.

- Roberts, Adam. The History of Science Fiction. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Sloane, Ernest. Symbolism. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1964.

- Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Auguste. Tomorrow’s Eve (L’Ève future). Translated by Alexis Lykiard. New York: Dedalus Books, 1997.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.