Each tyrant used propaganda in the way that best enhanced his strength as a leader.

By Mara McNiff

PhD Candidate, Ancient Mediterranean Art and Archaeology

The University of Texas at Austin

The Deinomenid brothers, who ruled during the 5th century BC in Greek Sicily, are credited as the tyrants who transformed the archaic city of Syracuse into a major world power and spotlight for art and commerce. Through these transformations, such as changes in artistic commissions and currency used in the ancient Greek city-states of Gela, Syracuse, and Aitna, the Deinomenid brothers Gelon and

Hieron could craft an identity for themselves that goes against the modern definition of the word “tyrant.” In its original Greek, the word tyrannos refers to an authoritarian sovereign, but did not have quite the pejorative connotation that it has today. Modern usage refers to tyrants as being cruel and using oppressive force to legitimize their power. The Deinomenids were able to use propaganda to reach the status of tolerant or benevolent tyrants during their reign in ancient Syracuse.

Each tyrant used propaganda in the way that best enhanced his strength as a leader. Gelon, a fair military commander and superior athlete, used coinage and the erection of temples to celebrate his success. Hieron, an avid patron of the arts, commissioned odes and plays from ancient playwrights and poets such as Aeschylus, Bacchylides, and Pindar, as well as drew comparisons between himself and the god Zeus Aitnaios in coins minted for the new-found city of Aitna, in the region around Mt. Etna. In an effort to appeal to the populous’ piety, both brothers drew inspiration from ancient Greek gods in their propaganda. Gelon is credited with drawing connections between his ancestry and the cult of Demeter.[1] He also cites his many military and athletic victories in coins minted for the cities of Gela and Syracuse.

The coinage of Gela, commissioned and supervised by Gelon, was the first step in securing the tyrant’s popularity in the Greek city-states. The coins of Gela contained an image of Gelas, an important river god associated with the colony. The inverse of the coin featured a design not previously seen on Greek currency: a naked rider on a horse (Figure 1). This most likely refers not just to the city’s strong soldier base, but specifically to Gelon and his role as a cavalry commander and his success in military campaigns. This image signaled a change in monetary representation, a shift from symbols that related to the local characteristics of a city to symbols connected to a specific person. Before Gelon’s coinage, a human figure on a coin was usually an anthropomorphized version of a god, but on the coins from Gela the figure of a man refers to an actual human being. This change in coinage is a considerable deviation, since the deities that were usually depicted on coins were replaced following Gelon’s rule, a fact which greatly helped the brother promote his power in Gela.

Gelon’s takeover of the ancient city Syracuse also signaled a change towards highly personalized imagery being represented on coins. A coin from 490 BC features an archaic-style two-horse chariot and driver with a winged Victory (or Nike in Greek) flying overhead on one side (Figure 2). The image of the goddess Nike holding a wreath above a chariot scene appears to be a direct reference to the athletic victories won by members of the Deinomenid family in the Panhellenic games.[2] Similarly, the depiction of a chariot can also realte to aristocracy, power, and war, which may reference the Deinomenids’ wealth and many victories in battle. It is significant to note that the coinage of Syracuse that predates Gelon’s takeover

of the city features a chariot scene with no victory goddess present.[3] The inverse of the coin features a female head surrounded by a ring of dolphins (Figure 2). The female head is believed to be the image of Arethusa, a nymph connected to the origin of Syracuse. Both images serve as another example of the coinage of the Deinomenids, featuring a symbol of religion on one side, and a symbol referring to their own achievements on the other. This connection Gelon created through his propaganda of coinage suggests that the tyrants are at equal level with the gods.

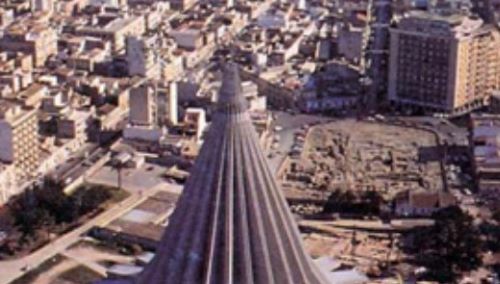

Gelon—who is credited with the takeover of the city of Syracuse and its installment as the capital of his rule—also used religion as propaganda by commissioning sanctuaries to Demeter, the goddess of fertility, and her daughter Kore when he repopulated Syracuse (Figure 3). The significance of this could have been to signify that Syracuse would prove to be a fertile and successful capital. However, it may have also been a clever move on Gelon’s part to draw a connection between his rule and the cult of Demeter, a relationship already established by one of his ancestors Telines. Herodotus records that Telines secured for his family and descendants the priesthood of the cult of the Earth Goddesses. A priesthood would mean special access to the members. A city whose ruler was a member of the priesthood of the Cult of Demeter would most likely be favored by the goddess herself and mean more abundance for Syracuse:

[A]s a result of party struggles in Gela, a number of men had been compelled to leave the town and to seek refuge in Mactrium on the neighbouring hills. These people were reinstated by Telines, who accomplished the feat, not by armed force, but simply by virtue of the sacred symbols of the Earth Goddesses. How or whence he came by these things I do not know; but it was upon them, and them only, that he relied; and he brought back the exiles on condition that he and his descendants after him should hold the office of Priest.[4]

Like Telines, conjuring this connection to the cult of Demeter proved useful to Gelon in his takeover of Syracuse because in this new city, unlike Gela, Gelon did not hold a respected position. He had forcefully brought in new inhabitants and displaced the locals. By using the religious propaganda of the cult of Demeter, Gelon could provide, “an external force to bind together this dangerous combination of peoples, made up of the angry, defeated Syracusans and the uprooted neighboring cities.”[5] Religious propaganda proved a useful tool to both brothers in the pacification of a population, especially in the takeover and foundation of a new city.

Hieron, who succeeded his brother’s rule as tyrant of Syracuse, is also credited with the establishment of a new city, Aitna, in the area surrounding Mt. Etna. It is believed that Hieron had the coin known as the tetradrachm of Aitna minted soon after the 476 BC foundation of the city, although the exact date is unknown (Figure 4). Like the other coinage produced during the reign of the Deinomenids, it contains important references to their tyranny, drawing a connection between their rule and the ancient gods. The coin of Aitna, however, contains perhaps the most personal and political messages of all the Deinomenid coinage. One side of the coin features the head of a satyr. The satyr is believed to be associated once again with Dionysus, the god of fertility. This connection was probably to establish Aitna as a land with a promising future in agriculture, especially since the land

surrounding Mt. Etna is known to be very fertile. Below the satyr is a small beetle and the word AITNAION (“of the people of Aitna”). The dung beetle that is present alongside the satyr can simply be seen as an image of good luck, one that was, “taken over by the Greeks from the Egyptians.”[6] This small detail on the coin evokes the hope that this new colony of Aitna will flourish and gain great fortune, especially in

connection with the satyr and agricultural developments.

The reverse image on the coin features the seated figure of Zeus and several secondary images which together create a complex and multifaceted message related to Hieron’s establishment and control of Aitna. The enthroned Zeus on the coin of Aitna is believed to be Zeus Aitnaios, the identity given to Zeus

when he is acting as the patron god of Mt. Etna. Zeus’ thunderbolt is adorned with a pair of wings. The image of wings could be a reference back to the Nike figure seen on the coins from Gela and Syracuse, and, in this way, hints at the Deinomenids’ many athletic and military victories. Additionally, the coin

features a tree with a bird, believed to be an eagle, on top of it, serving as another symbol for Zeus.[7] The triangular shape of the tree may also be interpreted as the peak of the mountain. This idea of the eagle on the peak of the mountain instills the idea that Zeus is god of the mountain, and therefore the city of Aitna. If the Mt. Etna region truly belongs to Zeus, then Hieron, as a “king” who has been given

the right to rule by Zeus, is simply protecting the land that rightfully belongs to the god, legitimizing Hieron’s claim over the city of Aitna. This image of Hieron as a “caretaker” for the gods further hinted towards his benevolence as a ruler. Instead of a lust for power, Hieron’s driving force is piety.

Another form of propaganda Hieron used in his search to legitimize his claim over the city of Aitna, and praise his success as ruler, was to commission a play by Aeschylus called Women of Aitna. The fact that Aeschylus left his native land of Greece and wrote a play for a Western Greek tyrant is completely

unprecedented: in Women of Aitna, Aeschylus praises the foundation of Aitna even though Hieron established the city by using extremely violent measures. This Greek tragedy was completely removed from its familiar environment:

“…the play has been removed from the context of the Great Dionysia to the context of a celebration of a specific event: the ‘foundation’ of Aetna….[I]t can not have been based in the tradition of questioning civic ideology that is central to many Athenian tragedies. The only ideology that could be presented in the play was ideology that Hieron wished to present to his subjects.”[8]

In Women of Aitna Aeschylus took figures from indigenous myth and made them subjects under Zeus, king of the gods. The play features the marriage between Thalia and Zeus. Thalia represents the indigenous sikels (natives of Aitna), as she was a nymph, daughter of Hephaestus, mother of the Palikoi in the indigenous myth from the cult of Palici, and is referenced herself in the play as Aitna.[9] Zeus, conversely, represents the foreign, or the mainland of Greece. This marriage between Thalia, the representation of Aitna, and Zeus, the representation of Greece was meant to draw a connection to the harmonious union of opposites, in this case, the indigenous peoples of Aitna and the new Grecian settlers who moved there during the foundation.

Aeschylus’ second staged form of propaganda commissioned by Hieron to help his favor also aimed at creating a unifying link between mainland Greece and other Greek controlled cities in ancient Sicily. While in Syracuse, Aeschylus restaged another of his famous plays, The Persians. The timing of Aeschylus’ visit in

the 470’s to Sicily is significant, as the end of the Persian War (c. 449 BC) and the birth of the classical period enforced a “negative attitude toward tyranny,” an attitude that did not fit with Hieron’s rule.[10] This play and its performance could have been Hieron’s attempt to show the mainland that colonies in the west were just as powerful and “Greek” as the city of Athens. For this reason, his choice to have the

play The Persians performed is significant. The Greek world had recently defeated Xerxes and “[b]y bringing an Athenian poet to his court, Hieron could emphasize Syracusan unity with the mainland and its defeat of the Persians.”[11]

This performance of The Persians can also be seen as an attempt to allow the population of Syracuse to celebrate that they too, as members of the Greek world, could claim a part of this victory. Hieron also used this play to pacify a newly conquered populace. By having the play performed shortly after taking Syracuse by force, Hieron may have been trying to de-emphasize the brutal actions of his family by

contrasting them with the atrocities of the Persians. Hieron was likely trying to convince the audience to rally together and turn their anger and energy towards a common enemy of the whole Greek world, instead of against Hieron himself. This performance of The Persians was also intended to help Hieron distance himself from the label of “a cruel ruler” by comparison to Xerxes, the newly defeated Persian king. The performance art provided entertainment for the inhabitants of Syracuse, while still providing

subtle messages regarding the power of the Deinomenids and their rightful claim to the colonies they controlled in Sicily.

An avid patron of numerous art mediums, Hieron also commissioned propaganda through poetry. Hieron’s next appointment was the hiring of Pindar and Bacchylides for the composition of Epinician poetry. Epinician poetry was, “lyric odes honoring a victor of the Panhellenic games.”[12] Pindar and Bacchylides both travelled to Sicily after having been invited by the Deinomenids to compose such

odes. These poems, and their performances, allowed the tyrants to justify their rule in the colonies through artistic expression. Using artistic propaganda by famous poets would help glorify Hieron’s athletic victory and further underline his strength and aptitude as a ruler. It is likely that these performances were done locally and would often include, “…important guests from elsewhere on Sicily.”[13] This allowed the Deinomenids to spread their propaganda not only before the inhabitants of their own colonies, but also among other significant individuals, and, thus, reinforce their

power over the rest of the island as well and forge powerful alliances.

Epinician poems were written to honor victors in the Panhellenic games. Bacchylides’ 3rd Ode (468 BC), written for Hieron’s chariot victory, refers to the glory of Demeter and Hieron in the first few lines: “Sing, Klio…of Demeter, queen of Sicily where the best grain grows, of Kore violet-crowned, and of Hieron’s

swift Olympic-racing mares.”[14] Bacchylides describes Demeter’s important connection to agriculture in Sicily and then immediately makes a statement regarding Hieron’s superiority in athletics. By referring to the goddess and Hieron together in the poem, Bacchylides suggests that Hieron is as renowned as the goddess and reinforces the Deinomenids’ connection to the cult of Demeter. Bacchylides then refers to

the king of the gods implying that Zeus himself has decreed that Hieron should hold a position of power in Sicily: “Ah, thrice-blessed is the man who has won from Zeus the privilege, more than all others, of ruling over Greeks.”[15]

After successfully eluding to a strong connection between Hieron and the goddess Demeter, Hieron commissioned more poems, this time from Pindar. The victory odes written by Pindar for athletic victors are considered to be, “some of Pindar’s most impressive and widely admired poems, such as the first two Olympians and first three Pythians.”[16] Pindar’s first Olympian ode, he uses myth to draw important connections between Hieron and Pelops, a hero killed by his father then brought back to life by the gods. Pindar writes that Pelops receives gifts from the god Poseidon: “a golden chariot and winged horses never

weary.”[17] Just as Pelops was aided and loved by the gods, Hieron appears to be protected by them as well: “Hieron, a god is overseer to your ambitions, keeping watch, cherishing them as his own.”[18] This connection between Pelops and Hieron further implies that Hieron is not only favored by the gods, but that any control Hieron claims is by divine right.

The poetry of Pindar and Bacchylides helped secure Hieron’s identity as a ruler favored and even appointed by the gods, but Hieron still needed to prove his own ability as a ruler, as odes can only do so much before real action and victory must be taken. The opportunity to prove Hieron’s prowess came with the Battle of Cumae. The Battle of Cumae, fought in the Bay of Naples, was originally a battle fought by Aristodemus, the tyrant of Cumae, and the Etruscans, natives of the Tuscan region on the mainland of Sicily.[19] Hieron contributed his army to that of Aristodemus for a successful victory over the Etruscans. To pay tribute to the gods after his victory, Hieron dedicated three bronze helmets to the Gods at the Sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia (Figure 5). An inscription on the helmets reads, “Hieron, son of Deinomenes,

and the Syracusans, [dedicated] to Zeus Etruscan [spoils] from Cumae.”[20] By setting up the helmet for

all visitors to see, Hieron ensures that they will be reminded, yet again, of when the West helped defeat a barbarian force. This subtle but pius form of religious propaganda aimed once again at solidifying Hieron’s strength as a ruler, victor for his people, and a tyrant blessed, if not chosen, by the gods.

With all of this considered, there appears to have been no method too extreme or controversial for the Deinomenid brothers when it came to legitimizing their hold over Sicily and solidifying their rule. This included promoting, manipulating, and exaggerating ties they had to religion through propaganda and to the land of Sicily to make it appear as if the gods themselves sanctioned the power that the family held. These actions also made it appear that the Deinomenids’ tyranny was rooted in the history of the island. Through the minting of coins, commissioning of architecture and written propaganda, among other art forms, the Deinomenid tyranny secured their place as successful, even popular rulers, and forged Syracuse’s identity as a major player on the world stage and as an ancient city rich with history for millennia to study.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Herodotus, The Histories (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd, 1972).

- Herodotus, The Histories (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd, 1972).

- Jones, A Dictionary of Ancient Greek Coins (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004), 156.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 7.153.2.

- White, “Demeter’s Sicilian Cult as a Political Instrument” (1964), 263-264.

- Holloway, The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily (London: Routledge, 1991), 125.

- Jones, A Dictionary of Ancient Greek Coins, 245.

- McMullin, The Deinomenids: Tyranny and Patronage at Syracuse (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004), 145.

- Dougherty, (1999), 89.

- McMullin, The Deinomenids, 143.

- Ibid, 145.

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- Morrison, (2007), 3.

- Bacchylides, Ode 3.

- Ibid.

- Morrison, (2007), 2.

- Pindar, Olympian Ode 1.

- Pindar, Olympian Ode 1.

- Diodorus, 11.51.1-2.

- British Museum Collection Database. “1823,0610.1” website listed under image, British Museum: Online.

Bibliography

- Bacchylide, and Arthur S. McDevitt. 2009. Bacchylides The Victory Poems. London: Bristol

Classical Press. - Green, Peter and Green, Peter. Diodorus Siculus, Books 11-12.37.1: Greek History, 480-431 BC the Alternative Version. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. https://muse.jhu.edu/

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey De Sélincourt. Middlesex: Penguin Books

Ltd, 1972. - Holloway, R. Ross. The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge, 1991.

- Jenkins, G.K. Ancient Greek Coins. London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd., 1972.

- Jones, John Melville. A Dictionary of Ancient Greek Coins. London: B.A. Seaby Ltd., 1986.

- McMullin, Rachel M. The Deinomenids: Tyranny and Patronage at Syracuse. University of

Wisconsin-Madison, 2004. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2005 - Pindar. Pindar’s Victory Songs. Trans. Frank J. Nisetich. Baltimore: John Hopkins University ]

Press, 1980. - White, Donald. “Demeter’s Sicilian Cult as a Political Instrument,” Byzantine Studies. 5:4 (

1964: Winter) 261 – 279 - “Bronze Helmet with an Inscription of Hieron I,” British Museum. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Epinicion (ode),” Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 11 Apr. 2014. - “From Italy and West,” Italy and West. Web. 12 Apr. 2014.

- “Greek Tetradrachm Gela Sicily (Replica) 466 B.C. to 413 B.C,” Coin Value. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

- “Tetradrachm of Aetna,” Europeana. Web. 14 Apr. 2014.

Originally published by Arcadia University, The Compass 1:4,4 (January 2017, 19-26), republished by ScholarWorks, open access under a Creative Commons license.