Introduction

The Late Middle Ages lasted from about 1300 to 1450 C.E., a time in which people experienced a shift in daily life. At the start of the Middle Ages, most lived in the countryside, either on feudal manors or in religious communities. Many owned or worked on farms where they produced their own food. But by the 12th century, towns were emerging around castles and monasteries and along trade routes.These bustling towns became centers of trade and industry.

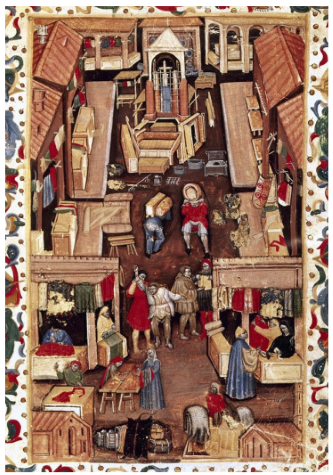

Almost all medieval towns were protected by thick stone walls and required visitors to enter through gates. Inside, homes and businesses lined unpaved streets. Since few people could read, signs with colorful pictures hung over the doorways of shops and businesses. Open squares in front of public buildings, such as churches, served as gathering places. People in the town might shop at the local market place or watch religious plays.

Most streets were very narrow. The second stories of houses jutted out, blocking the sunlight from reaching the street. With few sources of indoor light, houses were often dark, too. Squares and streets were crowded with people, horses, and carts—as well as cats, dogs, geese, and chickens. There was no garbage collection, so residents threw their garbage into nearby canals and ditches or simply out the window. As you can imagine, most medieval towns were filled with unpleasant smells.

The Growth of Medieval Towns

In the ancient world, town life was well established, particularly in Greece and Rome. Ancient towns were busy trading centers. But after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west, trade with the east suffered, and town life declined. In the Early Middle Ages, most people in western Europe lived in scattered communities in the countryside.

By the High Middle Ages, towns were growing again. One reason for their growth was improvements in agriculture. Farmers were clearing forests and adopting better farming methods, which resulted in a surplus of crops for them to sell in town markets. And because of these surpluses, not everyone had to farm to feed themselves. Another reason for the growth of towns was the revival of trade. Seaport towns, such as Venice and Genoa in Italy, served as trading centers for goods from the Middle East and Asia. Within Europe, merchants often transported goods by river, and many towns grew up near these waterways.

Many merchants who sold their wares in towns became permanent residents. So did people practicing various trades. Some towns grew wealthier because local people specialized in making specific types of goods. For example, towns in Flanders (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) were known for their fine woolen cloth. Meanwhile, workers in the Italian city of Venice produced glass. Other towns built their wealth on the banking industry that grew up to help people trade more easily.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, towns were generally part of the domain of a feudal lord—whether a monarch, a noble, or a high-ranking Church official. As towns grew wealthier, town dwellers began to resent the lord’s feudal rights and his demands for taxes. They felt they no longer needed the lord’s protection—or his interference.

In some places, such as northern France and Italy, violence erupted as towns struggled to become independent. In other places, such as England and parts of France, the change was more peaceful. Many towns became independent by purchasing a royal charter, which granted them the right to govern themselves, make laws, and raise taxes. Free towns were often governed by a mayor and a town council. Power gradually shifted from feudal lords to the rising class of merchants and craftspeople.

Guilds

Medieval towns began as centers for trade, but they soon developed into places where many goods were produced, as well. Both trade and production were overseen by organizations called guilds.

There were two main kinds of guilds: merchant guilds and craft guilds. All types of craftspeople had their own guilds, from cloth makers to cobblers (who fixed shoes, belts, and other leather goods), to the stonemasons who built the great cathedrals.

Guilds provided help and protection for the people doing a certain kind of work, and they maintained high standards. Guilds controlled the hours of work and set prices. They also handled complaints from the public. If, for example, a coal merchant cheated a customer, it might reflect poorly on all coal merchants. The guilds, therefore, punished members who had bad practices.

Guild members paid dues to their organization, which paid for the construction of guildhalls and for guild fairs and festivals. Guilds also used the money to take care of members and their families who were sick and unable to work.

It was not easy to become a member of a guild. Starting around age 12, a boy, and sometimes a girl, became an apprentice. An apprentice’s parents signed an agreement with a master of the trade. The master agreed to shelter, feed, and train the apprentice. In some cases, the parents paid the master a sum of money, but apprentices rarely got paid for their work.

At the end of seven years, apprentices had to prove to the guild that they had mastered their trade. To do this, an apprentice produced a piece of work called a “master piece.” If the guild approved of the work, the apprentice was given the right to become a master and set up his or her own business. Setting up a business was expensive, however, and few people could afford to do it right away. Often, they became journeymen instead. The word journeyman does not refer to a journey, but comes from the French word journée, for “day.” A journeyman was a craftsperson who found work “by the day,” instead of becoming a master who employed other workers.

Trade and Commerce

What brought most people to towns was business—meaning trade and commerce. As trade and commerce grew, so did towns.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, most trade was in luxury goods, which only the wealthy could afford. People made everyday necessities for themselves. By the High Middle Ages, more local people were buying and selling more kinds of products, including everyday goods like food, clothing, and household items. Different towns also began specializing in producing certain goods, such as woolen cloth, glass, and silk.

Most towns had a market, where food and local goods were bought and sold. Much larger were the great merchant fairs, which a town might hold a couple times a year. These fairs could attract merchants from many countries who sold goods from all over Europe, the Middle East, and beyond.

With the growth of trade and commerce, merchants grew increasingly powerful and wealthy. They ran sizable businesses and looked for trading opportunities far from home. Merchant guilds came to dominate the business life of towns and cities. In towns that had become independent, members of merchant guilds often sat on town councils or were elected mayor

Not everyone prospered, however. Medieval towns commonly had sizable Jewish communities, but in Christian Europe, they often faced deep prejudice. The hostility of Christians, sometimes backed up by laws, made it difficult for Jews to earn their living. They were not allowed to own land, and their lords sometimes took their property and belongings at will. Jews could also be the targets of violence.

One opportunity that was open to Jews was to become bankers and moneylenders. This work was generally forbidden to Christians because the Church taught that charging money for loans was sinful. Jewish bankers and moneylenders performed an essential service for the economy. Still, they were often looked down upon and abused for practicing this

“wicked” trade.

Homes and Households

Medieval towns were typically small and crowded. They were narrow and could be up to four stories high. Most of the houses were made of wood, and they tended to lean over time. Sometimes two facing houses would lean so much, they touched across the street!

Rich and poor lived in quite different households. In poorer neighborhoods, several families might occupy a single house with only one room in which they cooked, ate, and slept. In general, people worked where they lived. If a father or mother was a weaver, for example, the loom would be in their home.

Wealthy merchants often had splendid homes. The first level might be given over to a business, including offices and storerooms. The family’s living quarters might be on the second level, complete with a solar, a space where the family gathered to eat and talk. An upper level might house servants and apprentices.

Even for wealthy families, life was not always comfortable compared to life today. With fireplaces as the main source of heat and light, rooms were cold, smoky, and dim. Most windows were small and covered with oiled parchment instead of glass, so little sunlight came through.

Growing up in a medieval town wasn’t easy, either. About half of all children died before they became adults, and those who did survive began preparing for their adult roles around the age of seven. Some boys and a few girls attended school, where they learned to read and write. Children from wealthier families might learn to paint and to play music on a lute (a stringed instrument). Other children soon began work as apprentices.

In general, people of the Middle Ages believed in an orderly society in which everyone knew their place. Most boys grew up to do the same work as their fathers. Some girls trained for a craft, but most married young, usually around the age of 15, and were soon raising children of their own. For many girls, their education was at home, where they learned cooking, cloth making, and other skills necessary to care for a home and family.

Disease and Medical Treatment

Unhealthy living conditions in medieval towns led to the spread of disease. Towns were very dirty places. There was no running water in homes, and instead of bathrooms, people used outdoor privies (shelters used as toilets) or chamber pots that they emptied into nearby streams and canals. Garbage, too, was tossed into streams and canals or onto the streets. People lived crowded together in small spaces and usually bathed only once a week, if that. Rats and fleas were

common and often carried diseases. It’s no wonder people were frequently ill.

Many illnesses that can be prevented or cured today had no cures in medieval times. One example is leprosy, a disease of the skin and nerves that causes open sores. Because leprosy can spread from one person to another and can cause death, lepers were ordered to live by themselves in isolated houses, usually far from towns. Some towns even passed laws to keep out lepers.

Common diseases for which there was no cure at this time included measles, cholera, smallpox, and scarlet fever. The most feared disease was bubonic plague, known as the Black Death.

No one knew exactly how diseases were spread. Unfortunately, this made many people look for someone to blame. For example, after an outbreak of illness, Jews—often a target of unjust anger and suspicion—were sometimes accused of poisoning wells.

Although hospitals were invented during the Middle Ages, there were few of them. When sickness struck, most people were treated in their homes by family members or, sometimes, a doctor. Medieval doctors believed in a combination of prayer and medical treatment, many involving herbs. Using herbs as medicine had a long history based on traditional folk wisdom and knowledge handed down from ancient Greece and Rome. Other treatments were based on less scientific methods. For example, medieval doctors sometimes consulted the positions of the planets and relied on magic charms to heal people.

Another common technique was to “bleed” patients by opening a vein or applying leeches (a type of worm) to the skin to suck out blood. Medieval doctors believed that this “bloodletting” helped restore balance to the body and spirit. Unfortunately, such treatments often weakened a patient further.

Crime and Punishment

Besides being unhealthy, medieval towns were noisy, smelly, crowded, and often unsafe. Pickpockets and thieves were always on the lookout for vulnerable travelers with money in their pouches. Towns were especially dangerous at night because there were no streetlights. In some cities, night watchmen patrolled the streets with candle lanterns to deter, or discourage, criminals.

People accused of crimes were held in dirty, crowded jails. Prisoners relied on friends and family to bring them food or money, or else they risked starving or being ill-treated. Wealthy people sometimes left money in their wills to help prisoners buy food.

In the Early Middle Ages, trial by ordeal or combat was often used to establish an accused person’s guilt or innocence. In a trial by ordeal, the accused had to pass a dangerous test, such as being thrown into a deep well. Unfortunately, a person who floated instead of drowning was declared guilty because he or she had been “rejected” by the water.

In a trial by combat, the accused person had to fight to prove his or her innocence. People believed that God would ensure the right party won. Clergy, women, children, and disabled people could name a champion to fight on their behalf.

Punishments for crimes were very harsh. For lesser crimes, people were fined or put in the stocks (a wooden frame with holes for the person’s arms and sometimes legs). Being left in the stocks publicly for hours or days was both painful and humiliating.

People found guilty of crimes, such as highway robbery, stealing livestock, treason, or murder, could be hanged or burned at the stake. Executions were carried out in public, often in front of large crowds.

In most parts of Europe, important nobles shared with monarchs the power to prosecute major crimes. In England, kings in the early 1100s began creating a nationwide system of royal courts. The decisions of royal judges contributed to a growing body of common law. Along with an independent judiciary, or court system, English common law would become an important safeguard of individual rights. Throughout Europe, court trials based on written and oral evidence eventually replaced trials by ordeal or combat.

Leisure and Entertainment

Many aspects of town life were challenging and people worked hard, but they also participated in leisure activities. They enjoyed quite a few days off from work, too. In medieval times, people engaged in many of the same activities we enjoy today. Children played with dolls and toys, such as wooden swords, balls, and hobbyhorses. They rolled hoops and played games like badminton, lawn bowling, and blind man’s bluff. Adults also liked games, such as chess, checkers, and backgammon. They might gather to play card games, go dancing, or enjoy other social activities.

Townspeople also took time off from work to celebrate special days, such as religious feasts. On Sundays and holidays, animal baiting was a popular, though cruel, amusement. First, a bull or bear was fastened to a stake by a chain around its neck or a back leg, and sometimes by a nose ring. Then, specially trained dogs were set loose to torment the captive animal.

Fair days were especially festive, as jugglers, dancers, and clowns entertained the fairgoers. Minstrels performed songs,

recited poetry, and played instruments such as harps, while guild members paraded through the streets dressed in special costumes and carrying banners.

Guilds also staged mystery plays in which they acted out Bible stories. Often they performed stories that were appropriate to their guild. In some towns, for instance, the boat builders acted out the story of Noah, which describes how Noah had to build an ark (a large boat) to survive a flood that God sent to “cleanse” the world of sinful people. In other towns, the coopers (barrel makers) acted out this story, too. The coopers put hundreds of water-filled barrels on the rooftops. Then they released the water to represent the 40 days of rain described in the story.

Mystery plays gave rise to another type of religious drama, the miracle play. These plays dramatized the lives of saints, often showing the saints performing miracles, or wonders. For example, in England it was popular to portray the story of St. George, who slew a dragon that was about to eat the king’s daughter.

Basic Physical Geography – Europe’s Five Regions

At one time, when speaking of the relation of humans and the environment, people focused on how the environment affected people. The focus was on the effects of climate and climate events, physical geography, and natural disasters. Today, we’re aware that while the environment is affecting people, people and their technology are affecting the environment. Sometimes, the result is interactions that are quite complex. We’re going to explore the interrelationships between people and environment in medieval Europe.

Europe is often considered to have five regions. They are shown on the map. Regions have certain things in common, for example, physical geography, climate, and native plants and animals. We’ll discuss each of these regions in medieval times briefly.

• Northern Europe includes Scandinavia, Denmark, and Iceland. It has periods of very little daylight.

• Southern Europe is divided into three parts on three separate peninsulas. The three areas are the Iberian Peninsula (now Spain and Portugal), the Apennine Peninsula (now Italy), and the Balkan Peninsula (now a number of countries including Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, and most of Romania).Southern Europe is separated from the rest of Europe by mountain ranges, from west to east, the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Carpathian Mountains. It has the warmest climate in Europe.

• Eastern Europe forms the eastern border of Southern, Central, and Northern Europe. Some of Eastern Europe is as far north as Northern Europe, but it extends farther south as well.

• Western Europe includes what is now France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the islands of the Great Britain and Ireland. Notice that the Iberian Peninsula, although very far west, is classified with Southern Europe.

• Central Europe touches Western, Southern, Eastern, and Northern Europe. Much of its territory is landlocked.

Medieval European Agriculture

As much as 90 percent of the population of medieval Europe worked in agriculture. Because most people were directly affected by agriculture, this is the best place to begin a discussion of human-environment interactions.

Agriculture was quite different in Southern Europe and the rest of the area. Southern Europe is primarily dry and hot. Farmers in Southern Europe used the aratrum, a light plow suited for light farming in dry conditions. The aratrum makes a line in the soil for planting seeds. It disturbs the rest of the soil as little as possible so as not to lost precious moisture.

But the soil of Europe north of the Alps and Pyrenees is heavy and wet. It requires deep digging to prepare for planting and must be turned over so it will dry out. The moldboard plow was invented in ancient times for just this type of soil. But farmers continued to use the aratrum. Poor yields was one result. To get better yields, farmer would have to adapt to their region and climate.

Why would farmers not take advantage of this valuable technology? During the Roman Empire, people owned their own equipment and fields were square. The moldboard plow required six to eight draft animals to pull it—more than any one farmer owned. And it was difficult to turn the plow and team, so it worked best in long, rectangular plots.

So, the Romans did not adopt the moldboard plow. But after the fall of Rome, the possibilities of the technology and the manorial system developed together. The plow’s special needs contributed to the social changes that brought about the manorial system. Long fields that suited the plow fit easily into manor lands. Farmers on the manor joined resources and worked in sync, plowing, planting, and harvesting.

Other technology contributed to agricultural growth. Chief of these were horseshoes and the horse collar, which allowed faster horses to be substituted for oxen as draft animals, those that pulled farm equipment. Crop rotation through three fields, with one laying fallow, helped stop the depletion of nutrients from the soil and improved crop yields. So did increased use of manure to fertilize the fields. Introduction of rye and barley, which grow better in northern climates than wheat, improved nutrition. All of these developments led to increased food, which allowed for population growth.

The climate could also have notable effects on agriculture and, therefore, on people. The Medieval Climatic Optimum, also known as the Medieval Warm Period, affected Europe from about 1150 to 1350. It was followed by a century of cooling, and then, beginning in about 1500, the Little Ice Age. Although long-term changes were important, it was short-term changes—such as heavy rains and flooding—that were more dangerous to people. Just months of heavy rain, for example, could lead to crop failure. Even though technology led to food increases, one year of famine led people to eat their seed grain. So such crop failures could lead to repeated years of famine.

Crop failures happened repeatedly. Germany suffered a famine in 1243. Germany and Italy suffered from crop failures in 1258. And all of Europe suffered from the Great Famine of 1315 to 1317. The Great Bovine Pestilence of 1319–1320 killed a large percentage of the cattle and caused a long-term reduction in dairy products. People at the time weren’t aware of how much nutrition had been supplied through milk products. And people’s choices for food replacement didn’t supply adequate nutrition. Some scholars believe that the very high death rates in the Black Death (1347–1352) were partly due to these preceding events. In other words, germs, plus climate, plus human choices all contributed to the plague death tolls.

But with more people and developments in technology, specialization became possible and people interacted with their environment in new ways.

Water and Air Power

Waterwheels—invented in China and brought to the West via Muslim travelers—and windmills, which seem to have been independently invented in Europe, became widespread. Wheels and mills increased the amount of work that could be done. Waterwheels provided two to five horsepower, while windmills provided five to ten.

Mills were used, first of all, for grain. But they had other uses that brought about great changes. A plan for Cistercian monasteries, for example, set them beside a river and recommended using waterwheels to power numerous activities. Examples include milling corn, boiling beer, preparing wool by cleaning out the lanolin, cooking, running forges for metalwork. Mills were also used for tanning leather.

Trade

Industry increased rapidly. Wool from England came to be used in textiles produced in Bruges and Italy. Glassworks grew up in Venice. Metal work increased. With this greater specialization, trade became more important. A community could devote itself to industry and import its food or raw materials from elsewhere.

Trade created new possibilities and better quality products. Fleeces in Bruges were washed with black soap from Spain and alum from Asia Minor. Silk might be made into velvet in Lucca, Italy, and dyed a deep red with brazilwood that grew in Java or Sri Lanka and was sold to a merchant in India or China. Copper from Central Europe might be combined in the correct proportion with tin from England to make bronze. Of course, mining—whether metals, minerals, or stone—changed the environment.

Trade routes that already had existed were used more frequently now. Genoa and Venice battled for control of Mediterranean and Black Sea trade. For good and for ill, trade connected the world. In 1346, the trade routes shown in this map and others brought the products shown across Afroeurasia. From 1347 to 1352, the trade routes brought not only products, but the Black Death, even though people didn’t realize it at the time. The Black Death wouldn’t have killed so many if people had not helped carry it around the world. A combination of germs and human choice spread the plague across Afroeurasia.

Transportation

With specialization, there was an increased need to move goods from place to place. There was also more of a market for luxuries. Larger ships with a greater capacity for goods, such as cogs, were developed. This led to increased used of wood and more deforestation.

There were natural hazards involved in transport. Crossing fast rivers and high mountains provided one type of challenge. Dealing with very hot or cold weather provided a second type. In addition, merchants faced dangers from avalanches, heavy rain that washed out bridges, flash floods, mist and fog, and wolf attacks. But there were also hazards created by humans. Both water and land routes were used for transportation. While rubbish could make road travel difficult, weirs, low dams used to help control the flow of water, were used in many rivers. Weirs directed water into a waterwheel and to hold fish traps. They could contribute to upstream flooding. They could also block river transportation.

Changing a road could be as easy as walking in a different direction. But when the rivers didn’t go where people wanted to, sometimes they changed the environment to better suit their purposes. Two frequently used methods were canals and locks.

Medieval canals were of four types. They might divert, or change the course of, an existing river. They could run parallel to an existing river, to avoid an obstacle. They could provide a spur, or alternative outlet, to an existing river. Or they could form connections, either between two existing bodies of water or a city and the sea.

The last was important in the textile-producing cities in Flanders. These cities had to be able to receive wool and ship textiles. But the shoreline of the North Sea moved north. In the 12th century, the city of Bruges for example, became landlocked. A canal was dredged to reconnect it to the seaport of Damme.

But the levels of water in the Bruges canal were uneven. Pound locks were developed to allow ships to move from lower to higher water or vice versa. Unlike the other types of locks, which had only one gate, pound locks had two (the pound was the area between the gates). One gate was opened, and the ship moved in. Then the gate closed and the water level was changed to match the other side of the lock. The next gate was opened, and the ship moved smoothly into the higher or lower water on the other side.

Pollution

With a greater number of people, more food was needed. To grow more food, more land was needed. So one of the first results of a growing population was deforestation, turning forest into farmland. This led to other problems. Wood was used for fuel, both for homes and for industry. It was used in buildings and in ships. It contributed key parts of important weapons, such as long bows and gun stocks. With the wood supplies gone or used, people turned to other sources of fuel, like coal.

Combined with urbanization, which brought many people into close contact, this led to a decline in air quality. By the 1280s, people were already trying to prevent coal use in London because of the smoke. In 1291, Queen Eleanor of Provence, mother of King Edward I of England, suddenly moved from Gillingham, England, to Marlborough to get away from the evening smoke pollution.

Land and water pollution were also increasing. In London in 1421–3, around 61 percent of court cases had to do with what they called environmental “nuisances.” This could be rubbish blocking a road, broken roadways, or a dung heap or cesspool that wasn’t cleaned. Perhaps partly because of the growing importance of trade, keeping the streets clean had become more important in the 15th century. Human waste was dumped in streams, contributing to water pollution.

Originally published by Bardstown City Schools, republished under fair use for educational, non-commercial purposes.