An uneasy truce prevailed between the American Patriots and the British government – until it didn’t.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Stamp Act

The peace treaty that ended the French and Indian War in 1763 eliminated New France as a military threat to the British colonists, and marked the start of the march toward American independence. The war effort, and British Prime Minister William Pitt’s decision to retain large numbers of troops in the American colonies after the conflict, doubled Great Britain’s national debt.

In an effort to raise revenues, Parliament enforced the Navigation Acts, which listed specific commodities that could be shipped only within the English empire. However, Britain’s attempt to make the colonists abide by the shipping regulations generated little revenue due to an increase in smuggling. Pitt’s successor, George Grenville, took a different route to force the colonists to pay what he believed was their fair share for the services of the British army stationed in America.

In 1764, Grenville pressed Parliament to pass the Sugar Act—also known as the Revenue Act—that placed tariffs on sugar, wine, coffee, and other items imported by the colonies. The law angered Americans who claimed that Britain had no right to tax them because they had no representation in Parliament. Grenville countered that every member of Parliament represented every member of the British Empire, but the colonists refused to pay the tax, and continued to smuggle goods.

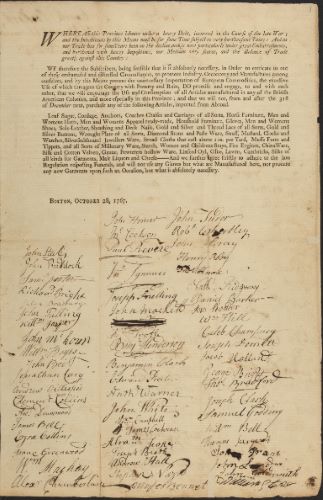

The inadequate funds generated by the Sugar Act forced Grenville and Parliament to enact a Stamp Act that placed taxes on all printed materials, including legal papers, playing cards, and newspapers. No one could sell pamphlets or newspapers or distribute diplomas or licenses without first purchasing special stamps and placing them on the printed material.

Grenville believed that the colonists would accept the tax with little objection since similar taxes were commonplace in England. But Americans considered the Stamp Act to be a direct tax—paid directly to England rather than to their own legislatures—and again challenged Parliament’s authority to tax without representation.

The colonists also grew suspicious of the build up of British troops in America, since the colonies finally seemed to be safe. The Proclamation of 1763, which Parliament enacted to prohibit white settlement west of the crest of the Appalachian Mountains, reinforced the fear that the British troops were not stationed in America to protect the colonists. Many Patriots believed that the British government planned to use the soldiers against Americans and suppress their freedom by enforcing the Navigation Acts and collecting taxes.

In October 1765, the Stamp Act Congress, comprised of delegates from nine colonies, petitioned Parliament to repeal the act. Grenville ignored the pleas of the colonists and ordered the tax to be implemented. Resistance to England’s attempts to tighten control over the colonies grew violent when organizations, such as the Sons of Liberty, staged riots and vandalized the homes of the stamp distributors. The mobs threatened the safety of the stamp agents and their families and intimidated them into resigning their posts. By the time the new law went into effect, it was unenforceable because there were no stamp distributors left in the colonies to sell the stamps.

Many Americans formed non-importation pacts that drastically cut the amount of goods purchased from England. British merchants, manufacturers, and shippers suffered from the reduced trade and pressured Parliament into repealing the Stamp Act. The colonists lifted their boycott on British goods and celebrated their victory against the Crown. Their jubilation, however, was short-lived.

On the same day Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, it passed the Declaratory Act, which reaffirmed England’s authority to pass any law it desired to bind the colonies and people of America. The colonists remained subordinates and the British government pronounced its complete and unqualified sovereignty over its North American colonies.

The Townshend Duties

The repeal of the Stamp Act did not end Britain’s plan to tax the colonies. In 1767, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend proposed enacting new customs duties on the most popular items imported by the colonies. Parliament approved The Townshend duties (also referred to as the Townshend Revenue Act), which taxed a wide variety of imports, including glass, lead, paints, paper, silk, and tea. Unlike the Stamp Act, the new levy was an indirect tax payable at American ports.

During this period, Parliament also implemented several administrative measures. It created a Board of Customs Commissioners to enforce trade regulations and established vice-admiralty courts to deal with colonists who violated the law. The British government paid the salaries of colonial governors with money collected from the Americans so the wages could not be withheld by colonial assemblies. Parliament decreased the number of British troops in North America and placed the financial responsibility for maintaining the presence of the remaining soldiers solely on the colonists.

Patriot leaders responded to the Townshend duties just as they did when the Stamp Act was announced—they boycotted British goods. This time, however, their efforts to disrupt the British economy did not produce the same results. Many colonists were not concerned with the new tax because it was small and indirect and, through the growing network of smugglers, they were able to find other avenues to get their goods. Samuel Adams, one of the most outspoken proponents of the non-importation pact, encouraged street mobs to involve merchants in the boycott, including those loyal to the Crown.

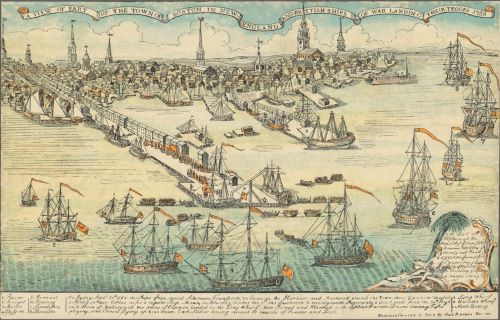

As conflict in the colonies intensified, Britain transferred two regiments of troops to Boston. The presence of the red-clad British soldiers patrolling the city streets convinced colonists that their liberties were being destroyed and resentment toward England escalated. Fistfights occurred regularly as Americans taunted the redcoats and dared them to fight back. Leaders of both groups realized that one incident could start a devastating riot.

On March 5, 1770, tension between the two forces peaked when a small group of colonists threw snowballs at a British soldier guarding the Custom House. The crowd grew in size as the participants’ jeers turned malicious. When the intimidating mob moved closer to the building, the British soldiers panicked and fired into the crowd. Five Bostonians were killed and several more injured. Among the dead was Crispus Attucks, a runaway mulatto slave and one of the primary instigators of the incident.

Colonists referred to the violent confrontation as the “Boston Massacre” and demanded justice. Future president John Adams offered his services as the British soldiers’ defense attorney to make sure they received a fair trial. All of the soldiers subsequently were acquitted except for two, who were convicted of manslaughter.

On the very day the Boston Massacre took place, Parliament at the urging of the new prime minister, Lord North, repealed all of the Townshend duties except that on tea. During the next two years, colonists’ attempts to enforce the boycott against British goods weakened, and an uneasy truce prevailed between the American Patriots and the British government.

The Boston Tea Party

In 1773, the British East India Tea Company faced bankruptcy. More than 17 million pounds of tea sat idle in warehouses, in part because American boycotts and smuggling damaged the English tea industry. The British government, set to lose a large amount of tax revenue if the company failed, ratified a Tea Act that allowed the company to bypass English and American wholesalers and sell directly to American merchants at reduced prices.

The act undercut American smugglers and angered other colonists who believed the British were using the low prices to trick them into paying the tea duty. Business owners worried that if Parliament could grant the East India Tea Company a monopoly on the colonial market, it could control all American commerce.

The Tea Act renewed the colonists’ resentment toward Parliament and prompted them to protest the British regulations. Mobs lined the ports in New York and Philadelphia and refused to allow the crews of the British ships to unload their tea cargo. The governor of New York declared that the tea could be unloaded only “under the protection of the point of the bayonet and muzzle of the cannon.”

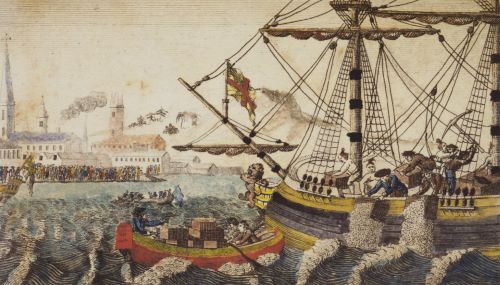

The citizens of Boston took a different approach to prevent the British ships from landing their cargoes. Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson was determined to force the issue in an effort to exert royal authority over the “rebels.” He ordered the three tea ships to remain docked in Boston harbor until their cargoes were unloaded. During the night of December 16, 1773, Samuel Adams and about fifty members of the Sons of Liberty disguised themselves as Indians and boarded the three ships. Onlookers huddled in groups on the dock and watched the band of colonists dump several hundred chests filled with tea into Boston harbor.

Colonists expressed mixed reactions to their countrymen’s defiant actions. Many citizens, such as Boston’s own John Adams, cheered the bold gesture; others, including Benjamin Franklin, were shocked at the destruction of private property. The people who condemned the rebellious action in Boston harbor believed that it threatened the existence of a civil society. They also feared that the outburst would bring severe repercussions from Parliament.

British authorities became furious when news of the Boston Tea Party reached London. King George III told Lord North it was time for the colonists to either submit to the Crown or triumph and be left alone. The prime minister was equally determined to test the Americans’ mettle and pressed Parliament to pass a series of measures to discipline the “haughty” colonists. The Boston Tea Party effectively stifled any public support in Great Britain for the American position.

In 1774, Parliament enacted four laws, collectively known as the “Coercive Acts,” designed to tighten Britain’s control over the colonies:

- The Boston Port Act closed the city’s harbor to all commercial traffic until the East India Company was paid for the destroyed tea.

- The Administration of Justice Act, dubbed the “Murder Act” in Massachusetts, transferred legal cases involving royal officials charged with capital crimes to Great Britain, where many colonists believed they would be set free.

- The Massachusetts Government Act increased the governor’s powers, decreased the authority of the local town meetings, and made elective offices subject to royal appointment.

- The Quartering Act, which was applied to all American colonies, required citizens to house British soldiers when other living quarters proved inadequate.

Although not considered part of the Coercive Acts, Parliament at the same time passed the Quebec Act that extended the Canadian border south to include the Ohio River Valley, land that was previously claimed by Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Virginia. Many colonists were convinced that the five laws, which they labeled the Intolerable Acts, directly threatened their liberty.

Lord North considered the colonies separate from each other and directed the Coercive Acts at Massachusetts as punishment for the Boston Tea Party. He assumed that the Americans generally were content to live under British rule and would not object to the restrictions that focused on just one colony. However, he did not realize that many Americans detested Britain’s claim to complete authority over the colonies. The Intolerable Acts served to stiffen American Patriot resistance toward Great Britain.

Published by AP Study Notes, from American Pageant 13th Edition by David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey (Houghton Mifflin Company, 08.24.2006), republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.