The Bardi bank had been one of the major players in the fourteenth century.

By M.T.W. Payne

In late 1493 the Venetian bookseller Cyprian Reglia found himself based in Paris. He was about twenty-seven years of age and bore a distinctive scar on the flesh of his left palm, by the wrist. Among other things, Reglia was acting as the business associate of the London-based bookseller Peter Actors. Actors, a native of Savoy, had been appointed king’s stationer in December 1485 and had outlets for his books in Oxford through his son Sebastian and his son-in-law John Hewtee.1 Another relative, Anthony Actors, imported books into London in 1478.2 The business was international for the nature of the book trade made this unavoidable. Although the printing press had been introduced into England by William Caxton in 1475 or 1476, very few had actually been set up by this date. Caxton himself had recently died and the only presses known to be operational in 1493 were those run by his successor Wynkyn de Worde and that recently established by Richard Pynson. A couple of other ventures into the domestic printing trade had come and gone, but as an industry it was yet to become firmly settled and by far the majority of printed books in circulation were to be imported from the Continent for some years to come.3 In the 1490s Actors was the chief importer of printed books into England, as he had been in the late 1470s and early 1480s, although his royal warrant exempted him from customs duties.4 The pay-off, as Peter Blayney argued, was presumably to import ‘whatever books Henry [VII] wished’.5 This involved not only foreign trading partners, but also family members established in helpful locations: Peter Actors’s nephew John Actors, for example, worked out of Lyons.6

In December 1493, Actors was required to pay for what we must assume was a batch of books, which he had imported from Paris via Cyprian Reglia. The shipment must have been of a significant size for the outstanding bill was for £20.7 Clearly Actors had no desire to travel to Paris to hand over the money to Reglia, so he made use of the sophisticated system for the transfer of money provided by the Italian bankers based around Lombard Street in London. In this instance he used his own bank, the Bardi, to transfer the funds, crediting his account on 18 December with the requisite cash. The bankers sent a bill of exchange to their agent in Paris, Manno Tannagli, and the sum was released to Reglia by the following 5 February. Tannagli wrote to the Bardi from Paris that he had released the money and Actors’s account was duly debited with the equivalent sum of £20 sterling, at the exchange rate of 100 gold scudi. Reglia had presented himself to Tannagli to claim the money, with the added security against identity fraud noted in the bank’s ledger, namely a description of the claimant’s age and a distinguishing feature. The whole process was therefore completed in two months, without either party to the payment having to leave his own city.

Reglia’s association with Actors, and England, clearly persisted. When Sebastian Actors, Peter’s son, died in 1501 in Oxford, Reglia claimed for money owing to him through his procurator John Aler.8 Peter Actors claimed his son’s binding tools through his son-in-law Hewtee. Reglia appears to have been based in Oxford from the late 1490s. In 1498 he had been involved in an action for debt at the court of common pleas brought by Bernard Dax, a brasier from London.9 Dax claimed a debt of £18 from John Palewell, a vintner based outside the north gate of Oxford, with Reglia and John Walker, a bookseller also from Oxford, acting as sureties. Regliahimself is described as being a scholar of the university, although he is not listed in the standard guide to the students of Oxford.10 The award of his BA and MA is not dated, but must be before 1502, from which date he is described in the University records as ‘magister’. The case was remitted on the payment of 100s, but this and other instances suggest that Reglia was engaged in fairly large transactions and that he was well-travelled along traditional routes followed by the books he himself traded in: Venice, Paris, London and Oxford. By 1523 he was firmly back in Paris, as principal of the Collège des Lombards at the University of Paris.11

The system of which Actors and Reglia made use to transfer funds was firmly established by the 1490s.12 The particular form of development of merchant banking stemmed from the Church’s proscription of usury, that is, the lending of money at interest.13 The growth of the banking sector reflects an Italian, and primarily Florentine, ingenuity with circumventing these laws. The preferred means of achieving this was through opportunities afforded by different currencies. To make international trade work, these currencies had to be exchanged, and rates of exchange were the tools by which profit could accrue. In order to facilitate this, there grew up around it the accompanying instruments by which this was achieved: bills of exchange and letters of credit.14 This might enable an individual to save himself the danger of carrying money – by purchasing from his local bank, perhaps in London, a letter of credit, then travelling to his destination on the Continent and cashing in the letter on arrival in local currency. Such a process is evident among the entries in the Bardi ledgers when, for example, Michel Morin credited his account on 10 July 1495 with £16, to which sum he soon after added a further £6 1s 8d, the whole amount of £22 1s 8d being redeemed by 15 September by Morin himself in Paris.15

The same principle applied to the acquisition by merchants of bills of exchange in order to transfer money to foreign trading partners or clients. The letter or bill was bought in sterling and cashed in a specified currency, at a stated exchange rate, which allowed inevitably for the banker’s profit. The interest was factored in but not technically charged. The bank made out the bill of exchange (in fact several copies were sent for reasons of security) and these copies were sent by them to the banker’s agent at the destination. The banks ran their own courier system and fixed time-periods were usually allowed within which the bill had to be claimed, based on the length of time the journey supposedly took: London to Florence, ninety days; Florence to Bruges, sixty. Some entries in the ledgers, however, demonstrate that these guidelines could be flexible. As a result, the merchant had the security of transferring sums of money safely over long distances and the bankers made a profit without in theory stepping into the sinful realms of usury by charging interest. It also enabled the bankers, who were of course also merchants, to move sums of money between markets for their own benefit. Because profits were based on fluctuations and variations in exchange rates, medieval banking was necessarily a fundamentally international business.

From the fourteenth century onwards various, largely Florentine, families had cornered the market in the new banking systems and the huge fortunes of such hereditary empires as the Medici and the Borromei were built on these financial operations.16 These were dynastic enterprises and the major families intermarried frequently. This meant that apparently rival firms often had complicated family connections. In addition, no individual firm, not even the Medici in their heyday, could have branches or agents in every major market, so there was necessarily a great deal of co-operation between them: a merchant approaching a branch on Lombard Street who wished to transfer sums to Rome needed to know that his bill could be cashed there by the Medicis’ correspondent. This might involve an arrangement with the Strozzi, who dominated business in that city.

The Bardi bank had been one of the major players in the fourteenth century, even described by the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani as one of the ‘pillars of Christendom’.17 Somewhat ironically, given the strictures against usury, the Church was one of the chief users of the banking system, since tithes and other financial levies needed to be regularly transferred from country of origin to Rome. The stress between the necessity of the system and moral condemnations of it is an ever-present factor in the later middle ages. However, the Bardi, along with the Peruzzi, went bankrupt in the late 1340s, primarily as a result of Edward III reneging on the huge loans they had advanced him to prosecute the Hundred Years’ War.18 Nonetheless, they did not go entirely out of business and by the early fifteenth century they had re-established operations sufficiently to reach into England once again. Various members of the family can be traced operating here from at least the 1420s. Giovanni di Agnolo di Zanobi de’ Bardi had arrived in London by 1454; and in 1465 he and Gherardo Canigiani agreed to be the active partners in a short-term limited partnership set up by the powerful Piero de’ Medici. By 1471 Giovanni de Bardi seems to have set up on his own, almost certainly in a sizeable property rented from the London draper William Brett, in or adjacent to Lombard Street, where agents of the other banks also congregated. But by the late 1470s Giovanni was spending increasing amounts of time back in Florence. At his death in 1488, the firm, known as the Heirs of Giovanni de’ Bardi and Partners, was taken on by his nephew Agnolo di Bernardo de’ Bardi. Agnolo also had another, legally separate, firm based in Florence, with the London firm dependent on the Florentine one. In the 1490s the manager of the London firm was Aldobrandino di Francesco Tannagli.19 Aldobrandino’s brother, Manno Tannagli, ran another company in Paris in partnership with Albizzo Del Bene and they represented the London Bardis’ chief partner outside Italy. The London Bardi branch specialized in transfers to the Low Countries, Paris and Italy. Although the London firm was fairly profitable in the early 1490s, after 1496 this appears to have changed and Agnolo wound up the company in 1502. Many of those working with or for the company, including members of the Bardi family, set up their own firms thereafter.20

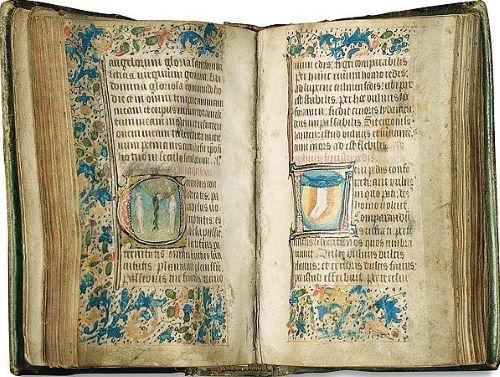

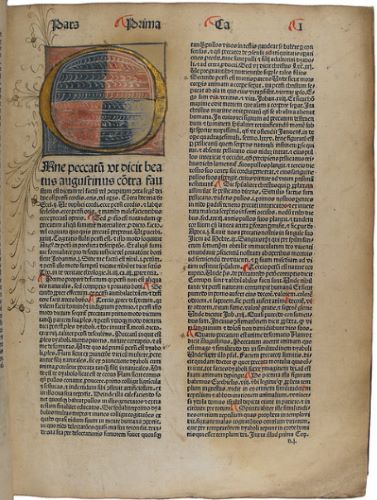

Although a significant number of the records of many Florentine banking houses have survived (the Arte del Cambio in Florence stipulated that all transactions had to be written down), relatively few of them relate to their operations outside Italy.21 Not surprisingly, most of them stem from the activities of their head offices. However, two ledgers from the Bardi bank’s London operations in the mid 1490s are to be found among the archives in the Palazzo Guicciardini in Florence.22 The ledgers are consecutive and cover the period 1492 to 1494 and 1495 to 1498 respectively. They are the final ledgers, drawn up to reckon the accounts, and would have been accompanied by other preparatory account books (journals, cash books etc.), which would have recorded the same transactions at an earlier stage. The entries in the ledgers make reference to some of these other working volumes and the page numbers on which the related entries can be found (these procedural details have not been included in the summary in the appendix to this essay). The financial transactions of hundreds of merchants, priests, nobles and other individuals based or operating in London are recorded. In the main these relate to transfers of funds from London ont o the Continent, very often via Manno Tannagli and Albizzo Del Bene’s company in Paris, but also to the Low Countries, to Rome and elsewhere.

Among all the drapers and grocers, scholars and priests there are listed the accounts of six particular members of the book trade; five of them are styled libraio, or bookseller, and the other, Hans Coblencz, ‘printer of books’ (‘inpresatore di libri’).23 Their names are given in Italian and sometimes it is clear that the bank clerk was unclear about how to record the curious sounding English – or German or French – words. So, for example, Peter Actors became Piero Attoris and Jean Huvin presumably lies behind the rather garbled ‘Giovanni Hwyn’. The entries under the respective accounts vary in length tremendously. In total the entries for the accounts of the six individuals in question amount to thirty-five items in the left hand (debit) side and forty-eight in the right hand (credit) side. However, the entries are completely dominated by the accounts of just two of these individuals: Peter Actors and Michel Morin. Their transactions comprise nineteen and fifty-six entries respectively (both debit and credit), over ninety per cent of the total. The other four individuals only conduct one transaction each, comprising one debit and one credit entry.

The entries themselves are usually vague about the precise purpose for the transfer of money. They give the name of the individuals to whom the funds are being transferred, but not the reason for the transferral. For example, in June 1495 Peter Actors sent £4 6s 8d to his nephew John Actors in Lyons (an example of Actors’s familial network); throughout 1496 Actors made a sequence of payments to Jean Richard, the well-known bookseller based in Rouen; and, in his final entry, in May 1497, Actors transferred the relatively small sum of £1 12s 8d to a certain Giovanni Testodis in Lyons. These payments almost certainly all represent orders for books, but it is difficult to draw firm conclusions beyond this. A great many books were published in Lyons and Rouen in 1495. But the close association between Actors and Jean Richard in Rouen, presumably reflecting a steady supply of volumes into England, is significant, even if it is not possible to tie them to particular editions.24

In some instances we might start to draw more tentative conclusions about the precise bibliographical purpose of the payments. In late 1494 Godfrey Aste, a bookseller from the Brabant whose identity is uncertain, appears for the only time in the ledgers. On 1 December 1494 he transferred to Nicholas Lecomte, a bookseller then apparently in Paris (although the text is not entirely clear at this point), £6 10s, equivalent to 30 gold scudi. Lecomte had redeemed the money by late January 1495. On 24 November 1494 Lecomte had published Johannes de Garlandia’s treatise on poetical metre, Synonyma, with its commentary by Galfridus Anglicus, printed for him by William Hopyl in Paris.25 According to the colophon of that book, Lecomte was then in London, based at St. Paul’s churchyard, so either he was travelling back and forth between Paris and London, or the money was, in fact, destined for Hopyl as Lecomte’s partner in the venture.

There are two other booksellers mentioned in the accounts who appear only once, neither of whose names provide completely certain identification. These are William Fox and, probably, Jean Huvin. In each of these instances their accounts seem to reflect occasions of them using the Bardi to move money which they themselves then collected; that is, as evidence of them travelling to and from the Continent. In the case of Huvin, this is particularly notable. In his entry Huvin credits his account on 20 June 1495 with £6 12s 6d (equivalent to 30 gold scudi), a sum which is then debited from his account on 27 February 1496, a full eight months later. The bill was exchanged for Huvin by Albizzo Del Bene, so this may be evidence of Huvin having been in London and travelling in early 1496 from there to Paris, rather than to Rouen, where he was normally based (although there are other instances of Del Bene cashing bills for Rouen). He must have been unknown to Del Bene, so we are given a physical description of him, along with his age at the time. This is significant not only for the details it gives us on Huvin’s birth in c.1457 and for his notable physical features, but also because it seems to provide support for the suggestion that he was, for a short period, in a form of partnership with Jean Barbier and Julian Notary.26 The argument centres on the printing of a copy of the Questiones attributed to Albertus Magnus by a new press near the church of St. Thomas the Apostle in London.27 Although the printers are not named, the device on the colophon used a mercantile mark which contained three sets of initials. Two of these are identifiable from a later colophon as the printer Julian Notary and Jean Barbier (although the precise identification of Jean Barbier is uncertain). But the third, ‘I H’, has remained disputed. Duff first argued that Jean Huvin was the most likely candidate, but Peter Blayney has recently thrown doubt on this, arguing that the other leading candidate for the owner of the initials, Inghelbert Haghe, is just as plausible since he was at least known to have been in England in 1505 to 1507 and 1510. Alternatively, the initials might not be those of a printer or publisher at all, but could even be those of another merchant who funded the venture. ‘If Huvin ever set foot in England’, Blayney stated, ‘the evidence is yet to be found’.28 It is the entry in the Bardi ledgers which provides the requisite evidence.

The other single-entry bookseller is something of a conundrum. In the ledger for 1497 his name is given as ‘Ghuglielmo Fox’, a bookseller from Normandy residing (dimorante) in London. It is possible that this represents an Italian clerk’s version of William Faques, who was later to become the king’s printer for Henry VII and certainly was from Normandy.29 Faques is only known to have been active as a printer in 1504 and 1505, some seven years later.30 Presumably, to be given the role of king’s printer, even at a date when this did not confer any particular exclusivity in printing, Faques must have had some significant experience in the book trade before 1504. This entry may provide evidence of Faques being active in London from as early as 1497 and apparently travelling to Paris, where he cashed in his own bill for £7 1s 8d. Alternatively, it may refer to someone else entirely. A stationer named William Fox is known to have been active at about this time and is to be found in court records from 1502.31

The only printer specified as such in the records is Hans de Coblencz, a German, recorded in his 1497 entry as a resident of Paris.32 He is, indeed, generally known to have been resident there, but as the London customs accounts show, he was certainly receiving shipments into England between 1502 and 1508, when his name is entered on the rolls.33 The Bardi ledger seems to demonstrate that prior to the spring of 1497 he had also travelled to England, at which point he returned to Paris, moving some £30 3s 4d (or 140 scudi) to be collected by himself in June of that year.34 The timing of Hans de Coblencz’s travels and the movement of his funds link to the most evident examples of the production and circulation of particular editions, for on the same day that Coblencz cashed in his own bill for over £30, he also received a bill for £6 from Michel Morin, the individual with by far the highest number of entries in the ledgers.35 Morin’s entries represent two thirds of the overall total relating to the book trade and are spread over three separate pages.

Morin himself, then aged about thirty, appears to have travelled from London to Paris on several occasions (which is not surprising, given that he is generally thought to have been Paris-based), in both the spring and autumn of 1495 and again in spring 1497, transferring for his own use the very large sums of £43, £22 and £43 respectively. Although he clearly relied heavily on the Bardi, he was initially unknown enough to require the requisite identity check, giving us the colourful additional information that he seems to have suffered from a slightly deformed little finger, which he could not properly extend.

Throughout 1495 to 1497 Morin made regular payments to the well-known Parisian bookseller Jean Petit, as well as to Hans Coblencz in Paris. While many of these payments doubtless represent the purchase of miscellaneous stock already printed, some of the entries surely cover payments for the production of two well-known works. On 11 April 1497 Pierre Levet printed in Paris an edition of Alexander Carpentarius’s Destructorium vitiorum, a best-selling treatise of invective and didacticism on contemporary morals by an obscure early fifteenth-century English writer.36 This edition was aimed squarely at the English market. The colophon informs us that it was printed by Levet for himself, Hans de Coblencz and for Michel Morin. The Bardi ledgers suggest that, if it is this publication which is covered and not another unknown volume, Morin did not deal with Levet but only with Coblencz and that Jean Petit was also, possibly, involved in the venture. The sums he was being paid by Morin were recorded under the same days as Coblencz. The latter’s presence in England until June 1497 may, therefore, be at least partially explained. And Morin’s journey to Paris, cashing in his large amount of over £30 on the same day that Coblencz received his £6 from Morin, can also be explained by this joint venture (although not the finer details of the business arrangements). Earlier and subsequent transfers of sums by Morin to Coblencz may represent other instalments of the same process. If so, this demonstrates the significant outlay required to fund an extensive print run, as well as further evidence for the commissioning of books for the English market by merchants based in England but using continental printers.

In autumn 1496 Morin transferred the equivalent of 60 scudi, in a number of instalments, to a certain ‘Awry’ or Arigho Charim, a German printer active in Paris, with further payments culminating in 100 gold scudi in May 1497.37 While it is not entirely clear who this represents, it may well be an Italian clerk’s attempt to make sense of a name given to him by Morin, a Frenchman, in England, referring to a German: Ulrich Gering, one of the three co-partners who had founded the first press in France at the Sorbonne more than twenty years before.38

The money paid by Morin to Ulrich Gering on 3 May 1498 (100 scudi, equating to £21 2s) may represent part-payment, probably the closing payment, for the printing and delivery of a well-known Sarum missal produced by Ulrich Gering and Berthold Rembolt for Wynkyn de Worde, Michel Morin and Pierre Levet on 2 January 1497.39 Whether the previous payments by Morin to Gering, of £13 in September 1496 and £26 in June 1497, represent part of the same long-running venture, it is not possible to be sure. If they do, this would represent a total investment by Morin, probably along with or on behalf of de Worde, of £60 or 280 scudi.

While the entries in the accounts of booksellers and printers clearly provide the most immediate evidence of the workings of the continental book trade at the end of the fifteenth century, there are other entries in the ledgers which also throw some light on this. The humanist Thomas Linacre, scholar and physician and friend of Erasmus, More, Colet and Grocyn, is believed to have spent almost all of the 1490s in Italy, from 1487 in Florence studying Greek under Politian and Demetrius Chalcondylas, then in Rome, before moving to Venice and Padua in the north and taking a degree in medicine from Padua in 1496.40 There he fell into the circle of Aldus Manutius and his efforts to promote the study of Greek. Linacre is not known to have returned to England until he reappeared in London in the summer of 1499. It is therefore surprising to find an account for him in the ledgers of the London Bardi branch.41 In it he is described as a studiente inghilese. His account records that on 21 June 1493, for a sum of 13s 4d (probably representing shipping expenses), Linacre had arranged through the Bardi for the delivery of his box of books (sua chassetta di libri), which was sent by Manno Tannagli from Paris to Oxford via London. He had made the payment to the London branch of the Bardi from Oxford via an unnamed English priest. The costs of delivery were settled that autumn and the books had been delivered by the end of October. Like others mentioned in the ledgers, Linacre’s travels to and from the Continent may have been more frequent than usually recognized.

The Bardi ledgers provide a wealth of evidence of the book trade at the end of the fifteenth century. They add another layer to our understanding of how this circulation of books operated and the reliance on the sophisticated Italian banking system for their importation and sale. But they also offer a demonstration of the sheer variety of merchants at work in London at the time. At first sight, the growth of the trade in printed books through London appears to have been almost exclusively in the hands of foreigners: importers and dealers active in London from the Low Countries, France and Germany, using the banking facilities of Italians based around Lombard Street. However, one must be cautious. Native London merchants who were involved in the trade may be obscured from view by their broader descriptors (draper, grocer etc.). William Caxton was, after all, a mercer and would very probably have been listed as such if he had featured in the ledgers. The general lack of detail within the entries confounds other attempts to pinpoint those involved. The majority of liturgical books, for example, seem to have been imported by grocers, and the financial transactions for such imports may well lie anonymously behind other entries in the ledgers.42 In addition, the ledgers provide an insight into only part of the mercantile chain which took a book from printer to bookshelf. As alien merchants, these importers could only sell on their wares in London wholesale; only freemen of the city were allowed to sell retail. The books imported by Morin and Actors and others would have required local booksellers to sell individually to customers. Nonetheless, for an understanding of the mechanism by which an increased volume of printed books began to arrive in England through London, and for the individuals involved in the trade, the Bardi ledgers clearly provide invaluable insights.

Endnotes

- For Actors, see E. G. Duff, A Century of the English Book Trade (London, 1948), p. 1; P. Blayney, The Stationers’ Company and the Printers of London, 1501–1557 (2 vols., Cambridge, 2013), i. 111–12. For his importation of books from Paris in 1480 (from Pierre Levet) and 1483, see P. Needham, ‘Continental printed books sold in Oxford, c.1480–3’, in Incunabula: Studies in Fifteenth-Century Printed Books Presented to Lotte Hellinga, ed. M. Davies (London, 1999), pp. 243–70.

- A. Coates, ‘The Latin trade in England and abroad’, in Companion to the Early Printed Book in Britain, 1476–1558, ed. V. Gillespie and S. Powell (Woodbridge 2014), pp. 45–58, at p. 48.

- M. L. Ford, ‘Importation of printed books into England and Scotland’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, ed. L. Hellinga and J. Trapp (7 vols., Cambridge, 1999–2019), iii. 1400–1557, 179–201; Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 47–8.

- ‘Between 1478 and 1491 Actors imported more than 1,300 books valued in excess of £140’ (C. P. Christianson, ‘The rise of London’s book trade’, in Hellinga and Trapp, Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, iii. 128–47, at p. 137). See also P. Needham, ‘The customs rolls as documents for the printed books trade in England’, in Hellinga and Trapp, Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, iii. 148–63; Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 111–12.

- Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 111. In 1501 Actors was paid 14s for 5 printed books for the king (TNA, E 101/415/3, fo. 65).

- Florence, Archivio Guicciardini, Carte Bardi 12, fo. 127. See Appendix.

- Florence, Archivio Guicciardini, Carte Bardi 11, fo. 248.

- Oxford, Bodleian Library, Hyp/A/2 (Reg D), fo. 93v, calendared in W. Mitchell, Registrum Cancellarii 1498–1506 (Oxford Hist. Soc., n.s., xxvii, 1980), pp. 95–7.

- TNA, CP 40/943; Mitchell, Registrum Cancellarii, p. 42.

- W Mitchell, Epistolae Academicae, 1508–1596 (Oxford Hist. Soc., n.s., xxvi, 1980), p. 56; BRUO (to AD 1500).

- O. Poullet, ‘Les Voyages des frères Verrazane’, Quiquengrogne,xxx (2002), 7–15.

- For the development of the Italian banking system, see R. de Roover, The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, 1397–1494 (Cambridge, Mass., 1963); T. Parks, Medici Money: Banking, Metaphysics, and Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence (London, 2005); R. A. Goldthwaite, The Economy of Renaissance Florence (Baltimore, Md., 2009).

- Dante consigned usurers to the 7th circle of hell, along with sodomites (Parks, Medici Money, pp. 13–5).

- I t should be noted that the Florentine bankers in London also provided a range of services, ‘from credit to the transfer of money, and from the sale to the purchase of goods’ (F. Guidi Bruscoli, ‘London and its merchants in the Italian archives, 1380–1530’, in Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, ed. M. Allen and M. Davies (London, 2016), pp. 113–35, at p. 122). This explains Actors’s purchase from the Bardi of taffeta and other cloths on 6 June 1495.

- Florence, Archivio Guicciardini, Carte Bardi 12, fo. 38.

- For the Borromei, see, e.g., F. Guidi Bruscoli and J. L. Bolton, ‘The Borromei bank research project’, in Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe: Essays in Honour of John H. A. Munro, ed. L. Armstrong, I. Elbl and M. M. Elbl (Leiden, 2006), pp. 460–88; J. L. Bolton, ‘London merchants and the Borromei bank in the 1430s: the role of local credit networks’, in The Fifteenth Century X: Parliament, Personalities and Power: Papers Presented to Linda S. Clark, ed.H. Kleineke (Woodbridge, 2011), pp. 53–73.

- On the Bardi see, e.g., F. Guidi Bruscoli, ‘John Cabot and his Italian financiers’, Hist. Research, lxxxv (2012), 372–93; Guidi Bruscoli, ‘London and its merchants’.

- E.g., E. Hunt, ‘A new look at the dealings of the Bardi and Peruzzi with Edward III’, Jour. Econ. Hist., i (1990), 149–62.

- Aldobrandino Tannagli appears regularly on the London customs rolls importing significant amounts of cloth, reflecting these merchant bankers’ roles as importers of exotic and luxury goods; and in the exchequer accounts, supplying similar goods to the court (e.g. TNA, E 404/85). See also S. Gunn, ‘Anglo-Florentine contacts in the age of Henry VIII: political and social contexts’, in The Anglo-Florentine Renaissance: Art for the Early Tudors, ed.C. Sicca and L. Waldman (New Haven, Conn.,and London, 2012), pp. 19–47.

- In early 16th-century Florence, the Bardi family forged close connections with the powerful Guicciardini family. This explains the survival of the ledgers among the Guicciardini family archives.

- For the survival of material relating to London and Bruges, see F. Guidi Bruscoli, ‘Mercanti-banchieri fiorentini tra Londra e Bruges nel XV secolo’, in ‘Mercatura è arte’: Uomini d’affari toscani in Europa e nel Mediterraneo tardomedievale, ed. L. Tanzini and S. Tognett (Rome, 2012), pp. 11–44; and for London only in Guidi Bruscoli, ‘London and its merchants’, esp. pp. 115–6.

- Florence, Archivio Guicciardini, Carte Bardi 11 and 12.

- See, e.g., Carte Bardi 12, fo. 312.

- Richard published many books for the English market (using various printers, including Martin Morin), including a Sarum Breviary, 3 Nov. 1496 (STC 15802); books of hours (Use of Salisbury) in 1494 (STC 15879) and 1497 (STC 15885); a Missale Saresberiense on 4 Dec. 1497 (STC 16171); an edition of John Mirk’s Liber festivalis in English on 22 June 1499 (STC17966); and a Manuale Saresberiense in 1501 (STC 16139).

- STC 11608a.7. See Catalogue of the Books Printed in the Fifteenth Century Now in the British Museum (London, 1908–2007), pt. viii (France), p. 135 (hereafter BMC). It is possible that Aste was pre-ordering copies of Lecomte’s own edition of the English sermon cycle, John Mirk’s Liber Festivalis (STC 17964), also printed by Wolfgang Hopyl, published on 26 Feb. 1495 (BMC, pt. viii, pp. 136–7). This was clearly intended for the English market but it seems more likely that the entry represented an order for copies of a book already printed. The Synonyma proved popular with English audiences, being reprinted by Pynson only two years later (STC 11609), then by de Worde in 1500 (STC 11610) and then in several more editions in the first decade of the 16th century.

- For this edition, see Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 63–7; BMC, pt. xi (England), p. 230.

- STC, p. 270.

- Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 65.

- Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 71–3; Duff, Century of the English Book Trade,p. 54. In one of his colophons Faques describes himself as ‘Guilliermum faques normanum’.

- Faques is recorded as an importer of paper in March 1503 (TNA, E 122/80/2). There is some slight evidence for an association with England back to 1495 (Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 72).

- Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 88 and 156.

- For Coblencz, see P. Renouard, Imprimeurs Parisiens (Paris, 1898), p. 75.

- Christianson, ‘The rise of London’s book trade’, p. 141.

- Apparently confirming the suggestion that Coblencz, like Jean Richard, ‘may have spent more time in England than has been realised’ (Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 93).

- Shipments of books into London in 1503 and 1506 by Michel Morin may well be in association with Coblencz, suggesting a long-standing partnership between these two (Christianson, ‘The rise of London’s book trade’, p. 141).

- Incunabula Short Title Catalogue <https://data.cerl.org/istc/ia00394000> [accessed 9 July 2019]. See BMC, pt. viii, p. 103.

- It is curious that we do not see transfers of money to his relative Martin Morin, a printer based in Rouen. Perhaps these were effected by a different means. For Martin Morin, see BMC, pt. viii, pp. 394–8.

- See BMC, pt. viii, pp. 20–31.

- S TC 16169.

- F or Linacre and his books, see V. Nutton, ‘Linacre, Thomas (c. 1460–1524), humanist scholar and physician’, in ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/16667> [accessed 2 Feb. 2019]; and J. Trapp, Erasmus, Colet and More: Early Tudor Humanists and Their Books (London, 1991), pp. 96–100.41Florence, Archivio Guicciardini, Carte Bardi 11, fo. 83.

- Blayney, The Stationers’ Company, i. 96. Another example may be provided by the draper William Wilcocks. He is known to have supported the publication in London of two books by John Lettou as early as 1480–1. Little is known of his other roles in the book trade. Wilcocks features in the Bardi ledgers and it is not impossible that some of his transactions relate not only to cloths.

Chapter 8 (165-187) from Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer (University of London Press, 10.31.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.