The Migration Period was a crucible in which the old world died and a new one was born.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

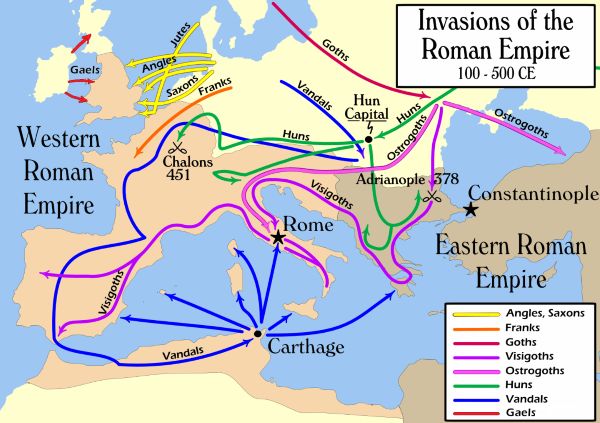

The Migration Period, often known as the “Barbarian Invasions” or the “Völkerwanderung” (German for “wandering of the peoples”), marks one of the most dynamic and transformative epochs in European history. Spanning roughly from the 4th to the 6th centuries CE, this era was defined by widespread population movements that fundamentally reshaped the political, cultural, and economic landscapes of Europe. Commonly situated between the decline of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of early medieval polities, the Migration Period was not merely a time of chaos and collapse, as once portrayed, but also one of profound change, negotiation, and synthesis between Roman and so-called “barbarian” cultures.

Historical Context: Rome and Its Peripheries

The Migration Period emerged against a backdrop of mounting internal pressures and external challenges to the Roman Empire, particularly along its northern and eastern frontiers. By the late third century CE, Rome was increasingly reliant on a tenuous balance between imperial overstretch and frontier diplomacy. Political instability, characterized by a rapid turnover of emperors and civil conflict, left the Roman state vulnerable to external pressures. Meanwhile, systemic economic weaknesses—marked by inflation, over-taxation, and declining agricultural productivity—further eroded the empire’s capacity to maintain its borders and military infrastructure.1 The so-called “barbarians” at the frontier were not isolated aggressors but participants in a long-standing and increasingly interdependent relationship with Rome. These groups—Goths, Vandals, Franks, Alemanni, among others—were deeply entangled in Roman trade networks, diplomacy, and even military service. By the 4th century, many of these peripheral societies were simultaneously influenced by Roman culture and compelled to challenge its authority.

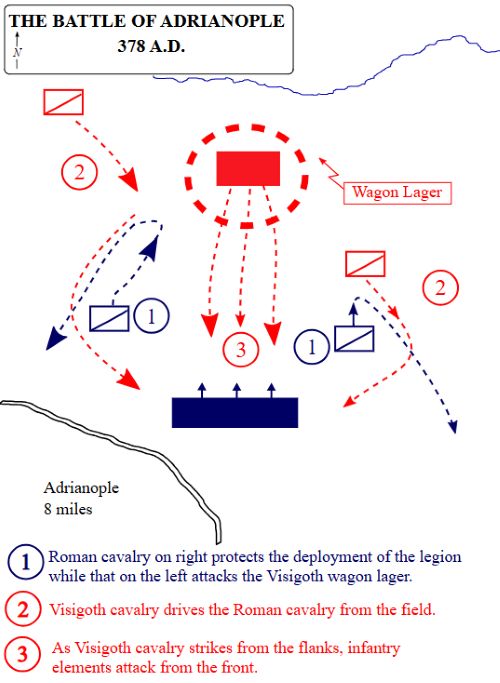

Rome’s peripheries were dynamic zones of cultural exchange and political flux rather than static borders between civilization and barbarism. Roman officials had long practiced the policy of foederati, granting land and legal status to barbarian groups in exchange for military service or loyalty to the empire. This approach was both pragmatic and risky. While it allowed the empire to supplement its military forces with skilled non-Roman soldiers, it also empowered foreign leaders and created semi-autonomous enclaves within imperial territory. A prime example of this policy was the settlement of the Tervings (later known as Visigoths) within the empire in 376 CE, ostensibly as refugees fleeing the advance of the Huns.2 However, Roman mismanagement and exploitation of these newcomers quickly led to rebellion, culminating in the catastrophic defeat of the Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE. This battle, in which Emperor Valens was killed, not only revealed the vulnerabilities of Roman military might but also signaled a transformation in the nature of imperial control—one increasingly dependent on negotiation and accommodation rather than coercive dominance.

The weakening of Rome’s control over its peripheries must be understood in terms of both decline and adaptation. Far from a uniform collapse, the empire’s retreat from the West unfolded unevenly across regions and decades. In many border provinces, Roman institutions persisted in altered forms well into the 5th and even 6th centuries. Local aristocracies, bishops, and military leaders often filled the void left by imperial retrenchment, maintaining elements of Roman administration and culture while navigating a new political reality.3 Simultaneously, the influx of barbarian groups into Roman territory was not always marked by conquest or destruction. Rather, it frequently involved negotiated settlements, intermarriage, and cultural assimilation. These groups were often Christianized—either through prior missionary contact or through conversion following settlement—and they adopted Latin, Roman law, and Roman urban structures to varying degrees. The line between Roman and barbarian thus blurred, particularly in regions such as Gaul, Hispania, and the Balkans, where hybrid societies emerged.

One of the most important features of this evolving relationship was the emergence of new identities forged on the imperial peripheries. The Roman concept of Romanitas—the cultural and civic identity associated with Roman citizenship—proved remarkably adaptable. It was embraced by barbarian elites who sought legitimacy and prestige within the Roman world. Gothic, Frankish, and Burgundian leaders adopted Roman titles, minted coins bearing imperial imagery, and employed Latin-speaking scribes and legal experts.4 Far from rejecting Rome, these rulers sought to position themselves as its heirs, even as they asserted new forms of sovereignty. This appropriation of Roman culture was not merely opportunistic; it was part of a broader process of cultural synthesis that redefined what it meant to be Roman in a post-imperial world. The frontier, rather than a rigid border, became a crucible in which Roman and barbarian identities were reshaped through conflict, cooperation, and convergence.

Finally, the Roman peripheries must also be viewed in the context of broader Eurasian transformations. The movement of the Huns across the steppe, beginning in the late 4th century, served as a destabilizing force that dislodged many Germanic and Iranian-speaking groups, pushing them toward Roman territory.5 These cascading migrations were not isolated events but part of a wider transcontinental shift, linked to climate fluctuations, economic disruptions, and power realignments from the Eurasian steppe to the Mediterranean. The Roman Empire, already weakened by internal decay, was ill-prepared to absorb the consequences of such large-scale demographic pressures. Nonetheless, the empire’s long engagement with its peripheries shaped the Migration Period not as a sudden break, but as a prolonged transformation in which new political entities emerged from the matrix of Roman imperial culture and its enduring legacy.

The Gothic Migrations and the Hunnic Catalyst

The Gothic migrations of the late 4th and early 5th centuries CE represented a pivotal shift in the dynamics of Roman-barbarian relations, marking the beginning of an irreversible transformation of the Western Roman Empire. The Goths—originally a collection of East Germanic tribes—had been living in the region north of the Danube and along the western fringes of the Black Sea for generations, interacting with the Roman Empire through trade, diplomacy, and intermittent conflict. Their internal divisions, most notably between the Tervings and the Greuthungs, did not preclude a shared ethno-cultural identity rooted in common language, traditions, and myth.6 However, by the 370s CE, external pressure in the form of the Huns—nomadic horsemen from the Eurasian steppes—forced these Gothic groups to reevaluate their position along Rome’s periphery. The sudden and violent advance of the Huns destabilized the balance of power along the Danubian frontier, pushing tens of thousands of Goths to seek asylum within Roman borders.

The Hunnic invasions acted as a powerful catalyst, not only for the movement of the Goths but for a domino effect of displacement that rippled across Europe. The Huns employed highly mobile, cavalry-based warfare, combining composite bows with rapid maneuvers that overwhelmed traditional defensive tactics.7 Their advance into Gothic territories was not merely a military episode; it constituted an ecological and political shockwave that broke long-standing power structures among Germanic and Sarmatian groups. The Roman Empire, caught unprepared, was forced to make a critical decision in 376 CE when the Terving Goths, under the leadership of Fritigern, petitioned to cross the Danube into Roman territory. The Romans, already facing internal challenges, reluctantly granted asylum. Yet their mismanagement of the resettlement—marked by extortion, starvation, and broken promises—ignited a revolt that culminated in the catastrophic Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE, where the Roman army was routed and Emperor Valens was killed.8 This defeat signaled not just a military disaster but a collapse in Rome’s ability to control the terms of barbarian settlement.

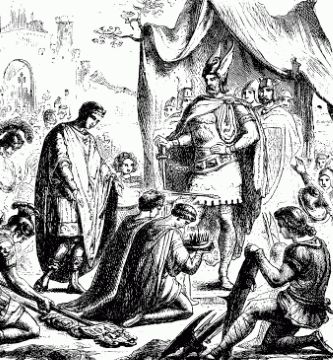

In the aftermath of Adrianople, Rome was forced to engage with the Goths as semi-independent actors rather than subjugated peoples. The imperial court, recognizing its military vulnerability, adopted a policy of accommodation rather than confrontation. Gothic groups were granted settlement rights as foederati, autonomous allies who supplied military service in exchange for land and nominal loyalty.9 This arrangement, however, allowed the Goths to remain politically and militarily cohesive under their own leaders. The most prominent of these was Alaric I, who rose to prominence in the late 4th century as a Gothic general in Roman service and later as an independent warlord. Alaric’s repeated campaigns in the Balkans and Italy, culminating in the sack of Rome in 410 CE, demonstrated the new political reality: barbarian forces were no longer merely invaders or mercenaries—they were claimants to imperial legitimacy. The Gothic sack of Rome was not an act of wanton destruction but a calculated assertion of status within the Roman world.10

The Hunnic factor remained a persistent and destabilizing presence in this broader milieu. By the early 5th century, the Huns had established a formidable confederation under the leadership of Attila, whose campaigns would reshape the political geography of both the Eastern and Western empires. The Huns were not merely external raiders; they engaged in complex diplomatic relations with Roman and barbarian powers alike, extracting tribute, demanding hostages, and manipulating alliances.11 Attila’s incursions into Gaul and Italy in the 440s and 450s CE placed immense pressure on Rome and its foederate allies, further destabilizing imperial authority. Ironically, it was not Roman armies but coalitions of Romanized barbarian forces—including Visigoths and Franks—who resisted Hunnic advances. The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 CE, where a Roman-barbarian alliance halted Attila’s progress, exemplified this shifting power dynamic. Rome had become a secondary actor in its own defense, increasingly reliant on former enemies turned allies.

Following Attila’s death in 453 CE, the Hunnic empire disintegrated rapidly due to internal rebellion and loss of cohesion. The power vacuum left in their wake allowed for the consolidation of Gothic polities within former Roman territory. Most notably, the Visigoths established a kingdom in southern Gaul and Hispania, while the Ostrogoths—another Gothic branch previously dominated by the Huns—migrated into the Balkans and eventually Italy under Theodoric the Great.12 These post-Hunnic settlements were not simple continuations of barbarian invasions; they were complex negotiations of identity, legitimacy, and state-building within the ruins of Roman imperial infrastructure. The Gothic migrations, catalyzed by the Hunnic storm, reshaped the Western Roman world into a mosaic of successor kingdoms that retained many Roman institutions while adapting them to new ethnic and political realities.

The Disintegration of Roman Authority in the West

The disintegration of Roman authority in the Western Empire during the Migration Period was not the result of a single cataclysmic event but the culmination of gradual, overlapping crises. Political fragmentation began in the third century and intensified in the fourth and fifth centuries as imperial power became increasingly decentralized. Emperors were often reduced to figureheads, with real authority frequently exercised by powerful generals or regional governors. The rise of rival military leaders, such as Stilicho, Ricimer, and later Odoacer, underscores the weakening of centralized imperial command.13 Simultaneously, economic decline—exacerbated by overtaxation, depopulation, and the breakdown of long-distance trade—eroded the material foundations of Roman governance. The imperial state, increasingly unable to fund its bureaucracy or maintain its infrastructure, relied more heavily on the military for coercive authority. This militarization of politics contributed to repeated civil wars, which in turn undermined the state’s ability to repel external threats.

The Western Roman Empire’s reliance on barbarian foederati further complicated its authority. These federated tribes were initially integrated into the imperial system to supplement dwindling Roman manpower, but their autonomy steadily increased. By the early 5th century, many of these groups, such as the Visigoths, Burgundians, and Vandals, had carved out semi-independent territories within the empire. Roman emperors were often compelled to negotiate from a position of weakness, offering land and legal recognition in exchange for military assistance or non-aggression.14 The sacking of Rome by Alaric’s Visigoths in 410 CE symbolized the declining prestige of the imperial capital and the failure of the old order to contain or control the very forces it had helped to empower. These so-called barbarian groups were not inherently antagonistic to Roman civilization; in fact, many of their leaders sought to legitimize their rule by adopting Roman customs, titles, and administrative models. Nonetheless, their presence within imperial territory marked a transition from Roman hegemony to a patchwork of regional powers.

By the mid-fifth century, the Western Empire was effectively a shell of its former self. The deposition of Romulus Augustulus by Odoacer in 476 CE is often cited as the end of the Western Roman Empire, but this moment was more symbolic than structural. Real power had long since shifted to local rulers, both Roman and barbarian.15 The Roman Senate continued to function in some form, and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire still considered itself the legitimate heir to Roman authority. However, in practice, the West was now divided among successor kingdoms that operated with increasing independence. These kingdoms—Visigothic Hispania, Ostrogothic Italy, Vandal North Africa, and Frankish Gaul—each maintained varying degrees of continuity with Roman institutions, blending Roman law, Christianity, and local traditions into new political frameworks. The disintegration of imperial authority thus gave rise not to a vacuum, but to a multiplicity of political experiments rooted in both continuity and rupture.

Religion played a crucial role in this transformation. The conversion of barbarian rulers to Christianity—initially Arian and later Nicene—helped to bridge the cultural gap between the Roman world and its successors. Bishops and ecclesiastical institutions, often among the few functioning remnants of Roman administration, assumed increasing political importance. In cities where civil administration collapsed, bishops took on roles traditionally held by governors, managing food supplies, negotiating with invaders, and maintaining public order.16 The Church thus became a vital repository of Roman identity, law, and language, helping to transmit Roman cultural values into the emerging post-imperial world. Simultaneously, it fostered a new, trans-regional identity that transcended ethnic and political boundaries. As such, the disintegration of Roman authority coincided with the consolidation of a Christianized Europe, where religious institutions supplanted imperial ones as the primary agents of social cohesion.

In the broader context of the Migration Period, the collapse of centralized Roman authority in the West should be understood not solely as decline, but as transformation. The Migration Period was marked by demographic shifts, environmental pressures, and evolving social structures. The influx of new peoples into Roman territories—whether as invaders, settlers, or allies—catalyzed the development of hybrid cultures. These new societies preserved many elements of Roman civilization while adapting them to local needs and conditions.17 Roads were still used, Latin remained the lingua franca of administration and law, and Roman ideas about governance endured in modified form. Yet the old Roman paradigm of a unified empire under a single ruler had given way to a more fragmented, pluralistic political order. The disintegration of Roman authority was thus both an end and a beginning: the collapse of an ancient empire and the genesis of medieval Europe.

Continuity and Change: Cultural and Religious Transformations

The Migration Period did not bring about the wholesale collapse of Roman civilization but rather initiated a complex process of cultural transformation. Even as Roman political structures crumbled in the West, many aspects of Roman culture—language, law, architecture, and administrative habits—persisted, often adapted by new rulers to legitimize their power. Latin remained the dominant language of administration and ecclesiastical discourse, especially in former Roman provinces, where it was maintained through the Church and elite education.18 The continuity of Roman legal traditions is also evident in the compilation of legal codes by barbarian kings such as the Visigothic Codex Euricianus and the Burgundian Lex Gundobada, both of which blended Roman legal principles with customary Germanic laws.19 These adaptations highlight the practical and symbolic utility of Roman norms in a time of political fragmentation. Rather than rejecting Rome, many barbarian rulers sought to present themselves as its heirs, appropriating its legacy to strengthen their rule and create a sense of continuity amid upheaval.

Religious transformation played a central role in shaping the post-Roman world. The spread of Christianity, already well underway by the fourth century, accelerated during the Migration Period, deeply influencing both Roman and barbarian societies. The conversion of barbarian kings—often beginning with their courts and followed by broader societal shifts—marked a key moment of religious integration. Initially, many of these groups embraced Arian Christianity, which had been popular among the Gothic tribes. However, over time, the shift toward Nicene orthodoxy, particularly under rulers like Clovis I of the Franks, helped to align emerging kingdoms more closely with the Roman Church and with the Eastern Empire’s theological positions.20 This realignment was not only a matter of faith but also of diplomacy and power, offering access to Roman ecclesiastical networks and legitimacy through the support of the Catholic clergy.

The Church became a major vehicle of cultural continuity and social stability. With the retreat of Roman civic institutions, bishops emerged as key figures in urban life, wielding both spiritual and temporal authority. In many regions, especially Gaul and Italy, the bishopric became the primary institution responsible for public welfare, tax collection, dispute arbitration, and even defense.21 The institutional structure of the Church provided a framework that could survive the collapse of imperial governance and continue to exert a stabilizing influence. Moreover, monasticism, exemplified by figures such as Saint Martin of Tours and later Benedict of Nursia, spread rapidly during this period, preserving literacy and classical texts while also promoting new forms of spiritual discipline and communal life.22 Monasteries would become repositories of Roman and Christian learning, transmitting cultural memory through the turbulent centuries to come.

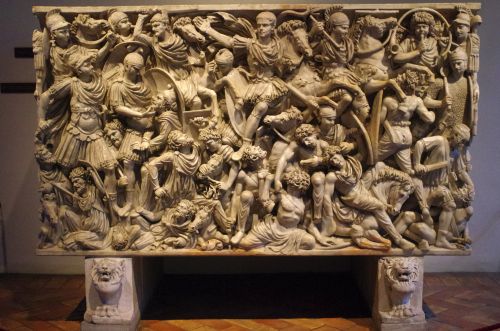

Despite the widespread transformations, the Migration Period was also a time of cultural synthesis. Roman, Christian, and Germanic elements fused in unique and regionally specific ways. Material culture—art, burial practices, domestic architecture—demonstrates both continuity with Roman forms and the emergence of new, hybrid traditions. For example, in Merovingian Gaul, elite burials combined Roman grave goods with Germanic weapons and Christian symbols.23 Artistic motifs, such as those found in illuminated manuscripts and church decoration, also reflect a blend of classical styles and northern influences. The integration of barbarian elites into former Roman provinces led to the creation of distinct post-Roman identities, which were neither fully Roman nor purely Germanic but something entirely new. These identities laid the groundwork for the medieval cultures that would dominate Europe in the centuries following Rome’s fall.

Ultimately, the Migration Period represents a crucial chapter in the longue durée of European cultural development. While the disintegration of centralized Roman power marked the end of antiquity, the enduring influence of Roman, Christian, and Germanic traditions ensured that this was not a period of cultural collapse, but of transformation. The institutions, languages, beliefs, and legal frameworks forged during this period became the building blocks of medieval Christendom.24 It was in the crucible of these centuries that Europe began to take on its post-imperial form, defined not by a single empire but by a constellation of kingdoms, dioceses, and cultures linked by shared religious faith and evolving memories of Rome.

The Eastern Empire and the “Other” Migration Period

While the Western Roman Empire succumbed to fragmentation and the rise of successor kingdoms, the Eastern Roman Empire—known to later generations as the Byzantine Empire—weathered the Migration Period with far greater resilience. From its capital at Constantinople, the Eastern Empire retained a centralized administrative structure, a robust fiscal system, and an intact professional army that enabled it to manage external threats more effectively than its western counterpart.25 Though it too faced waves of migration and invasion, particularly from the Huns, Slavs, and later the Avars, the Eastern Empire absorbed or deflected these pressures without suffering systemic collapse. Part of this resilience was geographical: the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Levant offered greater strategic depth and defensibility compared to the vulnerable provinces of Gaul, Hispania, and Britain. Equally important was the Eastern Empire’s ability to project ideological authority through the continuity of imperial institutions and the close alignment of Church and state.

The Eastern Empire was not isolated from the demographic upheavals that defined the Migration Period. The arrival of the Huns in Europe in the late 4th century had reverberations across the Danubian frontier, disrupting existing Gothic settlements and initiating a chain of displacements that would affect both East and West.26 The Eastern Roman response to these incursions was often diplomatic as well as military, involving strategic alliances, subsidies, and the settlement of foederati within imperial borders. The Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE, where Emperor Valens was killed by Gothic forces, underscored the severity of the threat posed by migrating peoples, yet the Eastern Empire ultimately recovered and learned to better integrate or neutralize such groups. By the reign of Theodosius II and his successors, a more stable system of frontier management had developed, combining military fortifications with calculated political accommodation.27 Unlike in the West, where migratory groups formed independent kingdoms, the East managed to retain sovereignty over its core territories.

A key component of the Eastern Empire’s success during the Migration Period was its ideological coherence and administrative adaptability. The emperor was seen as God’s representative on Earth, and imperial authority was closely tied to orthodoxy in Christian doctrine. This linkage of throne and altar enabled the empire to assert a unifying identity across diverse populations, especially as heresies and schisms threatened to destabilize both church and state. The Council of Chalcedon (451 CE), for example, sought to define Christological orthodoxy in ways that would both consolidate imperial control and address deepening regional divisions, particularly in Egypt and Syria.28 While these theological disputes occasionally exacerbated internal tensions, they also allowed the empire to redefine itself as the protector of true faith, a role that would gain increased significance in the face of barbarian Arianism in the West. The Eastern Roman Empire thus used religion as a political tool, weaving doctrinal conformity into the fabric of imperial loyalty.

Justinian I (r. 527–565) epitomized the Eastern Empire’s ambition during the later Migration Period, launching a concerted effort to reconquer the western provinces and restore Roman unity. His military campaigns, led by generals like Belisarius and Narses, succeeded in reclaiming North Africa from the Vandals, Italy from the Ostrogoths, and parts of southern Hispania from the Visigoths.29 While these gains were ultimately temporary and came at great cost, they reflect the Eastern Empire’s enduring sense of mission and capacity for revival even amid widespread disruption. Justinian’s reforms extended beyond the battlefield: his codification of Roman law in the Corpus Juris Civilis preserved and systematized centuries of legal tradition, providing a foundation for both Byzantine governance and later European jurisprudence. His extensive building program, including the reconstruction of the Hagia Sophia, symbolized the continued cultural and architectural vitality of the Eastern Roman world.

Despite its comparative strength, the Eastern Empire was not immune to the cumulative pressures of the Migration Period. The Balkans, in particular, remained a zone of chronic instability, as Slavic and Avar groups began penetrating deeply into imperial territory by the late 6th centuryo.30 These incursions, combined with recurring plague, fiscal strain, and military overreach, would test the empire’s durability in the centuries that followed. However, even as the political geography of Europe shifted dramatically, the Eastern Roman Empire maintained a remarkable degree of continuity. It preserved Greco-Roman culture, upheld centralized imperial authority, and served as a bridge between the classical world and the medieval Christian East. While Western Europe emerged from the Migration Period fragmented and feudal, the Byzantine Empire continued as a coherent and literate civilization, shaping the intellectual, religious, and political legacies of the post-Roman world.

Historiography and the Migration Debate

The historiography of the Migration Period has undergone significant evolution over the past two centuries, shaped by changing political climates, methodological innovations, and ideological assumptions. Nineteenth-century nationalist historians, particularly in Germany, often portrayed the so-called “barbarian invasions” as ethnic awakenings or the heroic emergence of proto-national identities.31 This ethno-centric narrative cast groups such as the Goths, Franks, and Lombards as unified peoples with stable traditions, migrating en masse to new homelands in a fashion reminiscent of biblical exoduses. Influenced by Romanticism and the growing power of the nation-state, these interpretations elevated the migrations to a foundational moment in the creation of modern European nations, particularly in northern and central Europe. The Migration Period, in this view, was not a collapse but a transformation guided by organic ethnic continuity.

However, the mid-twentieth century saw a significant shift in this perspective, particularly in the wake of the Second World War. Scholars began to question the ethnic essentialism of earlier models, scrutinizing the very notion of cohesive and homogenous “tribes.”32 The emergence of the “Transformation of the Roman World” paradigm, associated with historians like Walter Goffart and Patrick Geary, challenged the idea that barbarian migrations were large-scale ethnic displacements. Instead, these historians argued that so-called “barbarian” groups were often political constructs, formed through interaction with Roman institutions and identities rather than in isolation from them.33 According to this model, the Migration Period was less about destructive invasions and more about negotiated accommodation and gradual transformation within the framework of a declining, but still powerful, Roman order.

One of the central historiographical debates concerns the degree to which migration itself was a primary driver of historical change during this period. Critics of the traditional invasion model argue that the movements were relatively limited in scale, with elites—rather than entire populations—migrating and imposing new political structures on largely Romanized populations.34 Archaeological evidence, such as material continuity in pottery styles, settlement patterns, and burial practices, supports the view that local populations persisted even under new rulers. Furthermore, documentary evidence—though fragmentary—reveals the extent to which Roman legal, linguistic, and religious traditions endured. These findings challenge the notion of a “Dark Age” characterized by dramatic ethnic displacement, suggesting instead a more nuanced model of cultural synthesis and adaptation.

Nonetheless, not all scholars accept the minimalist interpretation. Researchers such as Peter Heather have argued for a renewed emphasis on the reality and scale of population movements, particularly under the pressure of external forces like the Huns.35 Heather maintains that the migrations had profound demographic and political consequences, particularly in the West, and that the barbarian groups, while fluid, did maintain a sense of shared ethnic identity rooted in oral tradition and kinship structures.36 For Heather and others in the “maximalist” camp, migration remains a central explanatory factor for the disintegration of Roman authority and the rise of successor kingdoms. This ongoing debate illustrates the contested nature of identity, ethnicity, and agency in Late Antiquity and the early medieval world.

Recent scholarship has sought to move beyond the binary of invasion versus transformation by integrating interdisciplinary methods, particularly from archaeology, genetics, and anthropology. DNA studies have begun to map patterns of migration and admixture, although their results remain complex and open to interpretation.37 Meanwhile, advances in critical theory and post-colonial perspectives have encouraged scholars to question earlier frameworks that privileged written Roman sources while dismissing oral traditions or non-Roman perspectives. Ultimately, the historiography of the Migration Period reflects broader debates about continuity, rupture, and identity in European history. Whether seen as a story of decline, transformation, or synthesis, the Migration Period continues to challenge historians to grapple with the interplay between narrative, evidence, and ideology.

Conclusion

The Migration Period was not a cataclysmic end to civilization but a profound reordering of the European world. It witnessed the disintegration of Roman political authority in the West, but also the emergence of new polities, cultures, and institutions that would shape the medieval and modern European landscape. While warfare, disruption, and population movement defined much of the era, so too did cultural syncretism, religious transformation, and the enduring legacy of Roman civilization.

In understanding this period, modern historians must look beyond simplistic narratives of fall and decline. The Migration Period was a crucible in which the old world died and a new one was born—not overnight, but over centuries of dynamic and creative transformation.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Peter Brown, The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150–750 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989), 20–24.

- Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 133–140.

- Walter Goffart, Barbarians and Romans, A.D. 418–584: The Techniques of Accommodation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 45–53.

- Guy Halsall, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 221–226.

- Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 64–70.

- Halsall, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 45-50.

- Peter Heather, Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 123–130.

- Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 138-145.

- Goffart, Barbarians and Romans, 31-40.

- Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, 84-91.

- Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 166–178.

- Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths, trans. Thomas J. Dunlap (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 283–296.

- Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 197-203.

- Goffart, Barbarians and Romans, 55-60.

- Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, 135-138.

- Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, 48-52.

- Halsall, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 341-349.

- Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000 (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 90–93.

- Goffart, Barbarians and Romans, 67-70.

- Ian Wood, The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751 (London: Longman, 1994), 25–30.

- Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, 85-91.

- Marcia L. Colish, Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition: 400–1400 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 22–27.

- Halsall, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 369-375.

- Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, 180-183.

- Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 145–151.

- Peter Heather, The Goths (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1996), 122–127.

- Michael Maas, The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 11–16.

- John Meyendorff, Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1989), 43–49.

- J. A. S. Evans, The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power (London: Routledge, 2000), 92–103.

- Florin Curta, The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 98–105.

- Wolfram, The History of the Goths, 5-8.

- Patrick J. Geary, The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 13–16.

- Goffart, Barbarians and Romans, 1-5.

- Halsall, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 10-17.

- Heather, Empires and Barbarians, 345-354.

- Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 142-149.

- Michael Kulikowski, Rome’s Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 189–195.

Bibliography

- Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

- Brown, Peter. The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150–750. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989.

- Colish, Marcia L. Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition: 400–1400. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Curta, Florin. The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Evans, J. A. S. The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Geary, Patrick J. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Goffart, Walter. Barbarians and Romans, A.D. 418–584: The Techniques of Accommodation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

- Halsall, Guy. Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Heather, Peter. Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Heather, Peter. The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Heather, Peter. The Goths. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1996.

- Kim, Hyun Jin. The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Kulikowski, Michael. Rome’s Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Maas, Michael, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Meyendorff, John. Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1989.

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- Ward-Perkins, Bryan. The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages, 400–1000. New York: Viking, 2009.

- Wolfram, Herwig. The History of the Goths. Translated by Thomas J. Dunlap. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751. London: Longman, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.