Candidates who defined themselves as Washington outsiders.

Introduction

In 2016, a billionaire businessman and the first woman nominated by a major party ran against each other for president of the United States. In very different ways, both candidates approached the presidency as outsiders, reaching beyond the traditional boundaries of US presidential politics. As outsiders, the 2016 candidates are noteworthy, but not unique; indeed, the 2016 race resonates with the legacies of outsiders who have come before. This exhibition explores the rich history of select individuals, parties, events, and movements that have influenced US presidential elections from the outside—outside Washington politics, outside the two-party system, and outside the traditional conception of who can be an American president.

Outsider, in this context, requires a dynamic definition. Featured stories explore candidates who defined themselves as Washington outsiders, such as World War II general Dwight Eisenhower, yet also those who were labeled or treated as outsiders because of their race, gender, or beliefs. In 1964, Republican Senator Margaret Chase Smith was the first woman to run for a major party’s presidential nomination. Twenty years later, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson built the Rainbow Coalition to unite marginalized and minority groups who felt excluded from politics and ran the most successful campaign by an African American candidate up to that point. Reformers whose principles are not represented by major party platforms have found a voice through third-party campaigns, such as that of the anti-slavery Liberty Party of the mid-nineteenth century. Still others have defined presidential candidacies in opposition to perceived outsiders, such as the anti-immigrant Know Nothing Party of the 1850s and the segregationist Dixiecrats in 1948.

These stories share common themes: determination to change the system, put pressure on major parties and force them to adapt, and give voice to new ideas though America’s presidential election process. These forces of change are not always positive; the stories represented here illuminate both the best and worst about America — both its capacity for and resistance to change in the face of its most reactionary and most idealistic impulses. Somewhere in between fall the stories of outsiders strategically navigating a political moment, forging their own political careers, and advancing their own political agendas.

Military Hero Turned President

No Political Experience? No Problem!

Thirty-nine of forty-three US presidents served in elected office in roles such as state governor, Congressional representative, or vice president prior to becoming president. The number of years of service varies widely—Woodrow Wilson was governor of New Jersey for only a year before running for the presidency, while Lyndon Johnson brought twenty-four years of congressional experience to the White House. The most common profession for presidents is lawyer, but there are outliers here too: Ronald Reagan was an actor and Herbert Hoover was a mining engineer.

In 2016, Americans heard a lot about the appeal of the outsider candidate, the person who approaches the presidency from beyond the insider field of Washington politics—and not for the first time. A common profile of the successful non-politician outsider in presidential elections has been the military hero, called to lead the American people after victory on the battlefield. In the nineteenth century, Presidents Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor each sought an electoral victory on the basis, in whole or in part, of their military leadership. In the twentieth century, President Dwight Eisenhower followed a similar formula to win the presidency following World War II.

The circumstances surrounding each election vary, but this section will examine how each candidate turned their lack of governing experience into a political asset and why major parties—perhaps the ultimate insider institutions—embraced these outsider candidates.

Old Hickory for President: Andrew Jackson, 1824 and 1828

Andrew Jackson had some insider credentials when he first ran for president in 1824; he had briefly served in Congress and as territorial governor. However, Jackson defined his candidacy not on his political experience but on his outsider status—a “man of the people” who proved his presidential qualifications on the battlefield, not the ballot, and who appealed to new white male voters, many recently enfranchised as states lifted property qualifications for suffrage rights during the early 1800s. Despite Jackson’s “common man” appeal, he was in fact a wealthy landowner whose fortune was wholly dependent on the labor of hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children.

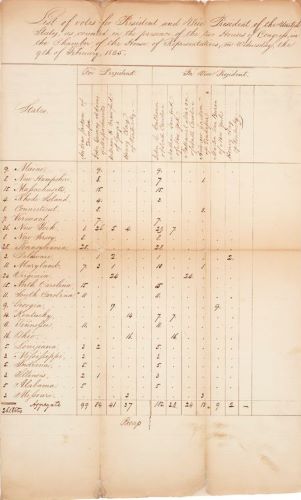

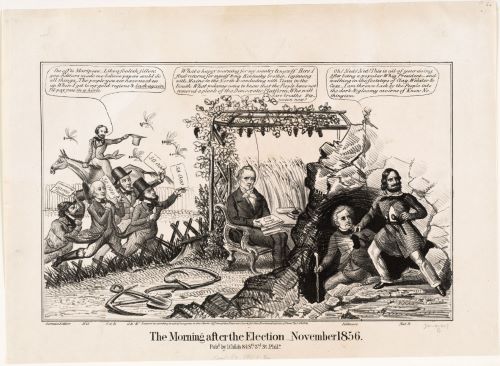

The election of 1824 was a turning point in the evolution of the two-party system. Four candidates, each largely bolstered by geographically sectional support, all ran for the same Democratic Republican party. Andrew Jackson won more votes than his opponents but, since Jackson failed to win a majority of votes, the power to elect the president went to the House of Representatives. There, Jackson was defeated by the alleged insider political alliance of his opponents, Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. House Speaker Henry Clay supported second place finisher John Quincy Adams, who won the presidency.

The 1824 defeat heavily shaped Jackson’s 1828 campaign. Jackson’s supporters doubled down on his image as military hero and favorite of the American people, while his opponents used his violent military record against him. In 1828, Jackson’s victory was decisive, ushering in the era of Jacksonian Democracy, which redefined the role of the “common” (white) man in American politics.

The Whig Party and Zachary Taylor, 1848

In the election of 1848, the Whig Party, which had emerged in the 1830s in opposition to the Democratic Party, turned to a politically inexperienced military hero as their candidate for president. Zachary Taylor, like Jackson, served in the War of 1812 and Seminole War, but had risen to national hero status as General “Old Rough and Ready” during the Mexican-American War (1845-1847).

Taylor, a slaveowner, had no political affiliation prior to his candidacy for president and, on some issues, blatantly conflicted with established Whig principles like their adamant anti-Mexican War stance and opposition to the expansion of slavery. The Whigs gambled that Taylor’s celebrity and broad public appeal would outweigh his lack of strong political conviction and help them compete against the Democratic party’s Lewis Cass and Martin Van Buren of the Free Soil Party. Ultimately, the Whigs won that bet, but lost party unity in the long run.

Taylor won the election by a small margin but, in the process, sharply divided the Whig Party between those who seized the opportunity for a celebrity candidate and those who remained true to political principle. The Whig Party never again succeeded in electing a candidate to the presidency and in the succeeding years dissolved amidst internal tensions over slavery. Over the following decade, the Republican Party emerged, replacing the Whigs as the second major party in opposition to the Democrats. The 1848 win was even less gratifying when Taylor died after less than a year and a half in office.

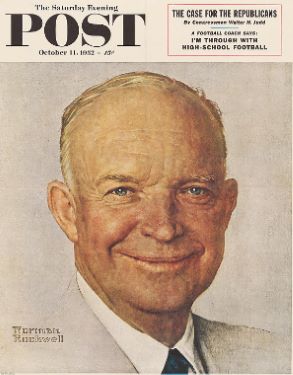

I Like Ike: Dwight Eisenhower, 1952

Dwight Eisenhower won the election of 1952 in a landslide and became a widely celebrated president who led the country during an era of economic prosperity. Prior to his presidential candidacy, however, Eisenhower was a political outsider; he had no public party affiliation and had never even voted.

Like Jackson and Taylor, Eisenhower was a military hero, most famous for his service as a five-star general and commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World War II. In 1948, Eisenhower was courted as a candidate by both the Democratic and Republican parties, but declined to run. In 1952, however, he declared that he was a Republican and agreed to run for president on a platform of opposition to communism, the Korean War, and corruption.

Eisenhower initially resisted pressure to actively campaign, and was still serving as a NATO commander in Europe during the first several months of his candidacy. He returned to campaign during the summer of 1952 and, already a household name, Eisenhower’s heroic, yet down-to-earth demeanor and catchy “I like Ike” slogan propelled him to victory.

Third-Party Reformers

Overview

Third-party candidates in US presidential elections have historically presented challenges to America’s two-party system, which has been particularly fixed as Democrat and Republican since the mid-nineteenth century. Falling all along the political spectrum, from conservative to moderate to liberal to radical, third parties and their nominees play an important role by offering voters reform alternatives to more established party politics and sometimes by campaigning on a single issue platform. Although they often struggle to compete with mainstream parties because of their relative lack of financial resources, third party candidates keep the possibility of reform in the minds of American voters and push more mainstream candidates to clarify and shift their political views.

Third-party presidential runs have met with mixed results. Socialist Eugene V. Debs ran five times for president on a workers’ rights platform, receiving 6% of the popular vote in 1912, his most successful election. 1924 Progressive Party nominee Robert La Follette, running on a broad progressive ticket, won 16% of the popular vote and 13 electoral votes from his home state of Wisconsin. Former Alabama governor George Wallace ran for president three times on a states’ rights platform, winning five southern states and 46 electoral votes in 1968. But a few third-party outsiders have had a profound impact inside the traditional two-party system—by shifting votes away from major parties and influencing the outcome of the election, or by achieving a degree of popular vote that threatened or beat that of a major party candidate. This section explores these third-party reform stories.

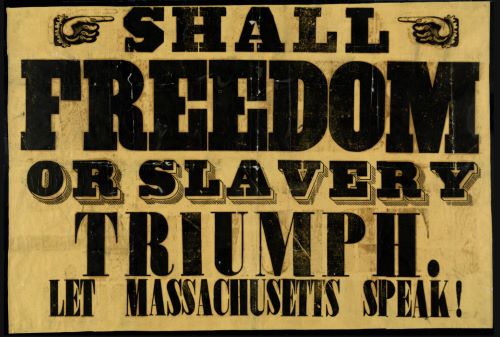

James Birney and the Liberty Party, 1840 and 1844

The Liberty Party was formed in 1839 in upstate New York in response to political fractures within the American abolitionist movement, particularly around the interpretation of the US Constitution. The American Anti-Slavery Society, run by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, denounced the Constitution as a “covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and advocated that abolitionists divorce themselves from its authority and mainstream politics in general to achieve reform. In contrast, founders of the Liberty Party interpreted the Constitution as an anti-slavery document, and hoped to use traditional political avenues such as elected office to accomplish anti-slavery reform.

Liberty Party founder James Birney was a Kentucky-born lawyer, former slaveholder, and celebrated convert to the abolitionist cause. The Liberty Party nominated Birney as their presidential candidate in 1840, although he only received 6,797 votes. Birney was once again nominated as the party’s candidate for 1844. This time, due to concerns over the annexation of Texas and its implications for slavery and politics, the Liberty Party received more popular support from voters who found the Whig Party candidate Henry Clay too compromising on the issue.

In the election, Birney won 62,103 votes or 2.3% of the popular vote, with 15,800 votes coming from voters in New York. Many speculated that the Liberty Party’s success in New York ironically helped throw a presidential victory from Clay to James Polk, the pro-slavery Democratic candidate. With New York, Clay would have had the majority of electoral votes.

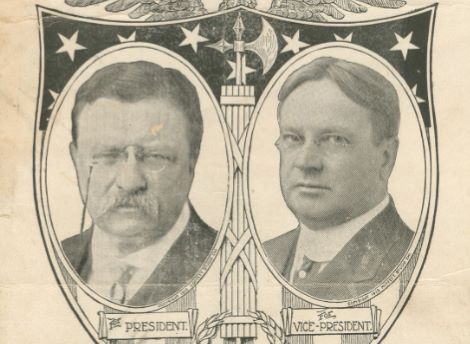

Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party, 1912

After seven years as US president from 1901 to 1908, Republican Theodore Roosevelt decided to re-enter the race for the presidency in 1912 to challenge his successor, William Taft. When he failed to secure the Republican nomination, Roosevelt formed the Progressive or “Bull Moose” Party and ran for president on its ticket. The Progressive Party advocated a broad reform platform, including farm relief, social insurance, limits on campaign contributions, and an eight-hour workday. In 1912, Roosevelt also became the first presidential candidate to formally endorse women’s suffrage and advocate for women’s participation in Progressive Party organizing. By the 1912 election, women had equal suffrage to men in six states and constituted 1.3 million voters. Through both organizing and voting, they formed an important part of the Progressive Party’s success in the 1912 election.

Throughout the election, Roosevelt and the Progressives challenged the success of Republican incumbent William Taft’s campaign, and created a race in which Roosevelt was perceived as the primary challenge to Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson. Despite an assassination attempt in October 1912, Roosevelt campaigned to the end. Wilson won the election, while Taft achieved only 23% of the popular vote and eight electoral votes. Roosevelt earned 27% of the popular vote and eighty-eight electoral votes (including states like California and Washington that had passed women’s suffrage legislation), making him the most successful third-party candidate in US history.

Ross Perot and the Reform Party, 1992 and 1996

After strife with the Bush administration about the Persian Gulf War, billionaire businessman Ross Perot decided to run as an independent candidate for president in 1992. Appealing to resentment towards established politicians and advancing himself as a vital third candidate option, Perot campaigned on a platform that included balancing the federal budget, opposition to gun control, the end of job outsourcing, opposition to NAFTA, and popular input on government through electronic direct democracy town hall meetings. Perot challenged his supporters to petition for his name to appear on the ballot in all fifty states.

After primary season in June 1992, Perot briefly led the election in polls with 39% of the popular vote over Democrat Bill Clinton and incumbent Republican George H. W. Bush. But by July 1992, Perot’s campaign faced internal challenges and Perot formally withdrew from the race. Although he re-entered on October 1, 1992, voters remained unsure whether he was officially running and his popular image was dogged by his images as a “quitter.” In spite of this turbulence, Perot won 18.9% of the popular vote, from voters spread across the country as well as across party lines. Perot ran again in 1996 as the Reform Party candidate and won 8% of the popular vote. With his challenges to mainstream politics, he emerged as one of the most successful third party candidates in US history, with the most support from across the political spectrum since Theodore Roosevelt.

Women Candidates

Overview

In July of 2016, Hillary Rodham Clinton became the first woman to be nominated by a major party for president of the United States. Also a candidate in the 2008 primary race for the Democratic nomination, Clinton’s career in presidential politics builds on an over 140-year legacy of women who have run for the nation’s highest office in a system that, until now, has by law and custom kept women outside the oval office.

Victoria Woodhull and Belva Ann Lockwood each ran for president at the helm of the Equal Rights Party in the 1870s and 1880s, decades before the ratification of the Constitution’s nineteenth amendment granted women the right to vote. Concurrent with the work of women’s rights activists and suffragists, each of their candidacies represented a radical forward-thinking interpretation of women’s rights to citizenship and political participation that would take a generation for the American government to recognize.

By the mid-twentieth century, with women’s rights to vote and hold office secured, Senator Margaret Chase Smith and Representative Shirley Chisholm broke new ground by running for presidential nominations by major parties. Though unsuccessful in seeking the nomination, each showed that a woman can and should be taken seriously as a legitimate contender for the US presidency, paving the way for Hillary Clinton’s historic 2008 primary campaign and 2016 nomination.

Victoria Woodhull, 1872

Victoria Claflin Woodhull defied the conventional gender norms of her time in a number of ways. Born in 1838, Woodhull became a businesswoman who founded a Wall Street stock brokerage, the founder and editor of her own newspaper, a free love advocate who spoke out against the societal limitations of marriage, and the first woman to be nominated for president.

Victoria Woodhull declared her determination to seek the presidency in an 1870 letter to the editor of the New York Herald and was later nominated by the Equal Rights Party in 1872. The party was a radical offshoot of the National Woman Suffrage Association and sought to build support among former abolitionists, black suffragists, and white women’s rights activists. Frederick Douglass was chosen as Woodhull’s running mate, but he never acknowledged or accepted the nomination. In her campaign speeches, Woodhull argued that, as citizens, women already had the right to vote and hold office as a result of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments—they just needed to use it.

Influenced by both socialism and spiritualism, Victoria Woodhull was a controversial figure, even in women’s rights circles. Woodhull was in jail on election day 1872 because of her role in exposing the sex scandal of popular minister Henry Ward Beecher. While she did receive some popular votes, it is unknown how many as no ballots listing her name survive.

Belva Ann Lockwood, 1884 and 1888

Belva Ann Lockwood followed Victoria Woodhull as the presidential nominee of the Equal Rights Party in the 1884 and 1888 elections. Like Woodhull, Lockwood was a suffragist and accomplished professional; she was an educator, a lawyer with her own practice in Washington, DC, and the first woman admitted to practice before the Supreme Court. As the 1884 election approached, Lockwood expressed frustration with the National Woman Suffrage Association leadership’s support for the Republican Party, writing that she did not “see any advantage of standing by the party that does not stand by us.”

Inspired by Lockwood’s political independence and commitment to action, the reform-minded Equal Rights Party selected Lockwood as their nominee and she accepted. Lockwood campaigned at rallies around the country on a platform that addressed a broad range of policy issues and included political equality on the basis of race and sex as a central tenet. Lockwood argued that although she could not vote, as an American-born citizen over the age of thirty-five, there was nothing in the Constitution that suggested she could not be voted for or could not hold office. Lockwood’s running mate was California suffragist Marietta Stow.

Lockwood received over 4,700 votes in eight states, though she contended that her votes were not counted fairly in some places. Lockwood ran again with less success in 1888 and, after that, continued to advocate for the causes of women’s suffrage and international peace. After a career spanning four decades, she died in 1917 at age eighty-six, still without the right to vote.

Margaret Chase Smith, 1954

In 1964, Republican Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine became the first woman to run for a major party’s presidential nomination. Smith began her national political career in 1940, when she won the Congressional seat previously held by her husband. She served in the House of Representatives and Senate for the next thirty-three years and was the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress.

In January 1964, Smith announced that she would be a candidate in the New Hampshire and Illinois Republican primaries. In her announcement speech, she listed the reasons that others had levied as to why she should not run: that the White House was a man’s world; the odds against her were too steep; she did not have the physical stamina to run a campaign; and that she did not have the financial or political backing to succeed.

Yet, Smith also detailed the reasons that she should run, including having more political experience than other candidates. Smith also argued that, whatever happened, she had the “opportunity to break the barrier against women being seriously considered for the Presidency.” Smith received little support from the Republican establishment, but was considered by many—from grassroots supporters to Washington politicians—to be a serious, highly qualified candidate. In a November 1963 press conference, shortly before leaving for Dallas, Texas, President John F. Kennedy said of Smith’s candidacy, “She is a very formidable political figure.”

Smith campaigned in selected states through the primaries and, though she did not win any states, earned the support of twenty-five convention delegates and became the first woman to have her name in consideration at a major party’s convention.

Unbought and Unbossed: Shirley Chisholm, 1972

Shirley Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to Congress and a founding member of both the Congressional Black Caucus and National Women’s Political Caucus. As a congresswoman representing Brooklyn, New York, Chisholm advocated for programs such as Head Start, food stamps, and education. In 1972, one hundred years after Victoria Woodhull’s run, Shirley Chisholm became the first African American person to run for president and the second woman, following Smith, to seek a major party’s presidential nomination.

Shirley Chisholm announced her candidacy for the Democratic Party nomination in January 1972 and ran on an anti-war platform that championed marginalized groups such as minorities, blue collar workers, and inner-city families and promoted social and economic justice for poor and urban communities. With her slogan, “Unbought and Unbossed,” Chisholm embraced her outsider status, rejecting the status quo of party politics that made financial backing and party approval political requisites.

Chisholm’s campaign received pushback from multiple angles, including among some African Americans who resented her gender and feminists who hesitated to endorse her because they did not think she would succeed. However, Chisholm campaigned throughout the primaries, winning votes in fourteen states, and earning 152 pledged delegates going into the Democratic convention. Chisholm was the most successful female presidential candidate to date but, like Smith, she looked ahead to others that would follow down the path she had helped to forge. She wrote, “The next time a woman runs, or a black, or a Jew or anyone from a group that the country is ‘not ready’ to elect to its highest office, I believe that he or she will be taken seriously from the start.”

Anti-Outsider Platforms

Overview

While many outsider candidates have changed and diversified the face of the American presidency, other political platforms formed to resist perceived outsiders and their influence on American politics. These anti-outsider platforms play to xenophobic and racist fears of disenfranchised and underrepresented “others” in the US political landscape—like immigrants and African Americans—and the potential changes to the social order that they might bring when politically empowered. Fears include imagined threats of crime and intermarriage that challenged native-born white entitlement to public spaces like schools and neighborhoods and economic opportunities like jobs. These platforms promise renewed policing of social and legal boundaries that maintain the status quo. Although they have historically not been successful at achieving the presidency, anti-outsider platforms shed light on the priorities of the significant numbers of voters who support them in the context of historical climates of discrimination.

Early anti-outsider platforms in the nineteenth century included resistance to immigration and naturalization from the Know Nothing Party and post-Reconstruction rejection of black enfranchisement from southern Democrats. By the mid-twentieth century, anti-outsider platforms like that of the Dixiecrats opposed federal intervention into civil rights issues, the integration of schools and the armed forces, and the empowerment of black voters through anti-discrimination voting laws. More recently, these campaigns take stands against undocumented immigration from Mexico while playing on similar fears about jobs and crime as their predecessors.

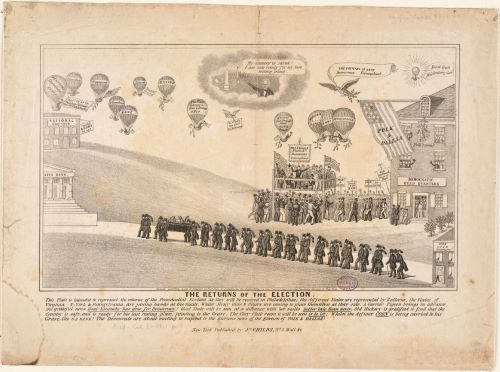

The Know Nothing Party, 1856

Formed in the early 1840s and popular through the 1850s, the Know Nothing movement was a reaction to the influx of German and Irish immigrants to the United States. Proponents saw these newcomers as a “foreign invasion” that threatened to influence politics and religion. They advocated to curb immigration and naturalization and played on white native-born fears about outsiders. More extreme members of the movement claimed that new Catholic immigrants would help subjugate America under the authority of the Pope. The movement organized in various social clubs and political forums across the country and created propaganda to draw adherents to their cause.

The Know Nothing Party, otherwise known as the American Party and the Native American Party, functioned as the political arm of the movement. By 1856, it had gained enough momentum to launch a bid for the presidency on a singularly focused platform—shutting down immigration to the United States and containing and marginalizing Catholicism. Former president Millard Fillmore ran as their candidate for a non-consecutive second term. Although not previously a nativist, he saw the Know Nothings as the only viable option for national unity in the face of the dissolution of the Whig Party and the ongoing struggle between other parties on the issue of slavery. Fillmore won only eight electoral votes but achieved 21% of the popular vote. Many 1856 Know Nothing adherents also voted in support of the fledgling Republican Party, which had started to court this demographic by campaigning around anti-Popery and bans on immigration.

The Dixiecrats, 1948

In the summer of 1948, conservative white southern Democrats formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, also known as the Dixiecrats, in reaction to President Harry Truman’s support of the civil rights plank in the national Democratic Party platform and his executive order to desegregate the armed forces. The Dixiecrats supported a segregationist agenda that rejected federal intervention and racial integration and advocated for the preservation of Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. Where rhetoric within the Dixiecrat campaign often focused on the federal government as the outsider threatening to take away power from states, this talk was a surrogate for fear of the political and social power that African Americans would achieve through activism and civil rights legislation.

The Dixiecrats held their one and only convention in Birmingham, Alabama in July 1948 and nominated South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond as their candidate for president. Their goal was to win 127 electoral votes in the election, denying both the Democrats and Republicans a majority and forcing the decision into the House of Representatives where they could negotiate the civil rights agenda. In November 1948, Thurmond received 2.4% of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes, carrying Alabama, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Mississippi. Significantly, this support came overwhelmingly from states with disenfranchised black majority populations, where white voters felt most threatened by the dissolution of segregation and the political possibilities of black enfranchisement. The Dixiecrats dissolved after the 1948 election but their political work began the weakening of the formerly all-Democratic “Solid South.”

George Wallace and the American Independent Party, 1968

Alabama governor George Wallace rose to national prominence in 1963 for his strong stance against the integration of public schools in Alabama. In his inaugural speech for his first term as governor in January 1963, Wallace famously advocated for “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Television viewers around the world saw Wallace’s “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” later that year, in which he would attempt to halt the enrollment of black students Vivian Malone and James Hood at the University of Alabama. Wallace sought the Democratic nomination for president in 1964, 1972, and 1976, but ran as a third-party candidate for the American Independent Party in 1968 with the most success.

In 1968, Wallace ran on a platform similar to that of the Dixiecrats twenty years earlier that rejected the outside intervention of the federal government on civil rights issues like education while also capitalizing on reactive white fear and racism stirred up by recent civil rights gains like the Voting Rights Act, school integration, and anti-discrimination laws. In his campaign, Wallace appealed to white working and middle-class voters who feared for the safety of their jobs, neighborhoods, and schools, by positioning the oppressed and overlooked “redneck” as the new outsider displaced by federal law and black activism. In the general election, Wallace won five states—Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas—and their 46 electoral votes. More surprisingly, he won 13.5 % of the popular vote or almost 10 million votes that reflected widespread support from across the country.

African Americans and Presidential Politics

Overview

African Americans have been active political organizers throughout the nation’s history—petitioning, organizing, voting, protesting, and serving their communities from the era of early republic through the Abolition Movement, Reconstruction, and the era of lynching and segregation. By the mid-twentieth century, as the number of African American voters grew rapidly through both legislative action and political empowerment, presidential candidates were required to court their votes by appealing to their concerns. This growing constituency also made it possible for black candidates to run for office with more success, which legitimized the idea that black candidates were contenders for the presidency for an increasingly broad and interracial group of voters.

In 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party brought national attention the issue of black voter disenfranchisement in Mississippi and demanded that the Democratic Party confront the reality of injustice. Eight years later, as Shirley Chisholm ran for president, members of the National Black Political Convention met to strategize about how to build on the legal gains of the Civil Rights Movement and continue to work towards expanded political power for African Americans. In 1984 and 1988, Jesse Jackson ran for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination and earned support from a broader, and more diverse group of Americans than had previously supported a black presidential candidate, laying the groundwork for the successful candidacy of Barack Obama, who was elected as the first black president, in 2008.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, 1964

Founded in April of 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) challenged the authority of the all-white Democratic Party that dominated Mississippi politics and disenfranchised black voters. Bolstered by Freedom Summer voter registration efforts in black communities throughout the state and alternative “Freedom Ballots” organized in parallel with official elections, MFDP hosted its own state convention and elected its own delegation to the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

MFDP organizer and Mississippi native Fannie Lou Hamer had endured brutal physical abuse in retribution for her efforts to vote freely. Her televised testimony at the Democratic convention’s credentials hearing convinced many Americans that the MFDP delegates should be recognized. However, when threatened with a walkout by other white southern delegations, President Lyndon Johnson and other party leaders refused to unseat the Mississippi delegation in favor of the MFDP. Instead, they offered a weak compromise to the MFDP: two at-large non-voting seats. The MFDP refused these terms.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s presence at the convention drew national attention to the brutality of black voter disenfranchisement in Mississippi and throughout the South and helped catalyze support for the Voting Rights Act, which was passed the following year. Their dismissal by the Democratic Party reinforced the importance of their work; expanding black voting rights and political power would be critical in order to ensure representation in institutions of political power like party conventions and elected office.

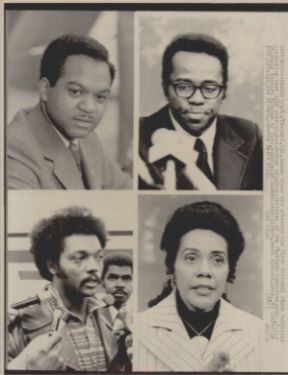

The National Black Political Convention and Shirley Chisholm

The early 1970s was a turning point moment in which black political leaders sought to employ the legal gains of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power ideology towards a new era of black political empowerment at local, state, and federal levels. In 1972, as Shirley Chisholm ran for the Democratic Party nomination, the National Black Political Convention met in Gary, Indiana, bringing together thousands of delegates from black communities and organizations across the country to foster unity and determine a black political agenda by which current and future candidates for office would be assessed.

While both the convention and Chisholm’s candidacy represent landmark events, they were not necessarily politically coordinated. Chisholm was proud of her black identity, but she rejected the idea that she was the candidate solely representing the interests of black America. The convention, led by some of her colleagues in the Congressional Black Caucus, did not endorse her. Some felt that Chisholm had run without consulting established black leadership and believed the first African American presidential candidate should have been a man. Many black leaders and officeholders endorsed George McGovern, though Chisholm’s platform most clearly aligned with the national black political agenda the convention had put forth.

While the alliance of various organizations that had made the National Black Political Convention possible dissolved amidst differing philosophies, the Gary convention had tangible results. The late 1970s and 1980s witnessed a rapid expansion of African American elected officials at the local, state, and congressional levels, including Shirley Chisholm’s reelection as Congresswoman, an office she held until 1983.

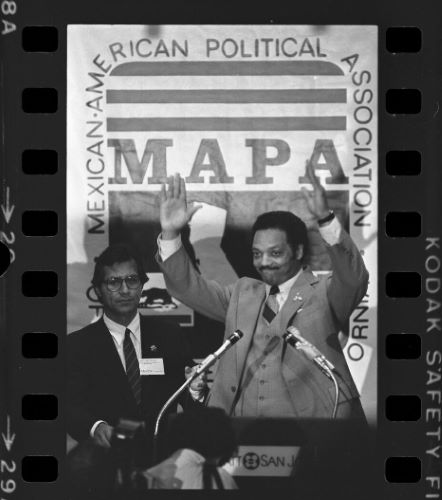

Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition, 1984 and 1988

Rev. Jesse Jackson began his public career as a civil rights organizer alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In late 1983, with decades of organizing experience but no experience in elected office, Jesse Jackson declared his candidacy for the Democratic Party’s 1984 presidential nomination. Jackson leveraged the black political mobilization of the 1970s and expanded its inclusivity, appealing to the concerns and interests of a “Rainbow Coalition” of marginalized and minority citizens, including African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, women, gay people, poor people, and more.

The Democratic Party of the early 1980s had relied on the votes of these marginalized communities, but in the view of many, fell short of making a real effort to represent them. Amidst the Reagan Revolution, which reduced government support for social and education programs and civil rights initiatives, Jesse Jackson led a grassroots campaign paired with efforts in voter registration. In doing so, he built his voter base as he went, diversified the Democratic Party, and offered a political vision inspired by the activism of the Civil Rights era and the legacy of the New Deal. Jackson did not win the nomination, but surprised many by winning five primary contests and finishing with 3.2 million votes.

In the 1988 campaign, Jesse Jackson was even more successful, winning more primaries and earning broader support across both white and minority voters. Jackson also commanded greater recognition and respect from the party. Though Jackson did not win the nomination, twenty-three year old future president Barack Obama and millions of Americans watched Jackson prove that an African American could be broadly accepted as a legitimate candidate for president.

Barack Obama, 2008

Barack Obama, the Hawaii-born son of a Kenyan father and American mother, began his 2008 presidential campaign as a relative newcomer to Washington politics. He was the first term junior senator from Illinois who ran for the Democratic Party’s nomination in part on his status as a party outsider, espousing a fresh vision of hope and change, a counterargument to Washington politics as usual. Obama would become the first African American president of the United States.

Early in the election cycle, it was Hillary Clinton, not Obama, who commanded strong support in many black communities and among black political leaders. However, the primaries proved that Obama’s message resonated and that he could earn votes across the country, from overwhelmingly white Iowa to South Carolina, where he garnered support from the majority African American voter base. Barack Obama went on to win the presidential election with 69.5 million votes, the most ever cast for a presidential candidate to date.

Barack Obama’s victory was undoubtedly influenced by the campaigns of Chisholm and Jackson and the activists of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the National Black Political Convention, and countless others that came before him. However, in critical ways, Obama represented a shift; he had not been a part of the Civil Rights Movement or Black Power-era political organizing. Instead, he was part of the generation that was heir to the political landscape that these movements helped create—where people were registered and could vote regardless of race, class, or creed and where an African American could be recognized as a presidential candidate that represented America, including but not limited to black America.

This exhibition was curated by DPLA staff members Samantha Gibson and Franky Abbott with materials contributed by DPLA Hubs.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), October 2016, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.