Torquemada pioneered the cryptic: a puzzle form that, like modernist poetry, unwove language and rewove it anew.

By Roddy Howland-Jackson

Editorial Assistant

Harper’s Magazine

This article, Beastly Clues: T. S. Eliot, Torquemada, and the Modernist Crossword, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Introduction

Nottingham Zoo was having a bad month. On January 4, 1925, the acquisition of a thirteenth ostrich had led to public pressure “to train one of them for police purposes”, a feat supposedly “accomplished some years ago on an ostrich farm in Florida”, reported the Evening Post.1 A fortnight later, a “fugitive monkey” named George escaped from the zoo, bruising a naturalist’s knee on his way out.2 To add insult to (genicular) injury, the zoo was under siege by “requests for aid in solving ‘cross-word’ puzzles’”: “What is a word in three letters meaning a female swan? What is a female kangaroo, or a fragile creature in six letters ending in TO?” Nottingham Zoo, as one reporter suggested, “has enough to do with the care of its own animals, and cannot act as consultant to the world at large”.3 The poor zookeepers were at the thin end of a puzzle wedge; fated, as Ernie Bushmiller joked in his popular comic strip, to serve buckets of alphabet soup to animals prized and poached for their phonemes alone.4

The “crossword craze” of the 1920s had hit Britain like a “meteorological depression”, and, as was traditional, Americans were to blame.5 Following the publication of the first crossword in New York World by Arthur Wynne in 1913, the Tamworth Herald lamented the misfortune of a nation where “10,000,000 people have caught the infection of unprofitable trifling”, estimating the loss of productive American labour to crosswords at roughly five million hours per day.6 In the UK, so much damage had been inflicted by ham-thumbed solvers on the dictionaries of Wimbledon that all such reference works were withdrawn from public access.7 Thesaurus sales skyrocketed while library use crashed.8 By the time Vladimir Nabokov published the first Russian krossword in 1924, the Nottingham Evening Post’s “world at large” estimation was quite right: the grid truly had run a girdle around the earth.

Commentators on both sides of the Atlantic were aghast at the forfeiture of intellectual capital to a game that seemingly traded on automatic, transactional thinking. To the New York Times in 1925, crosswords were little more than “a sinful waste in the utterly futile finding of words the letters of which will fit into a prearranged pattern, more or less complex”.9 (During 2018, the New York Times netted roughly $33 million from crossword products alone).10 In 1920s London, The Times, likewise, sneered that “everywhere, at any hour of the day, people can be seen quite shamelessly poring over the checkerboard diagrams, cudgelling their brains for a word meaning idler, or whatnot”.11

Modernist Crosswords

As newspapers were lamenting the labour frittered away on crossword puzzles, they also had cross words to say about another form of cryptic writing and time-consuming interpretation: modernist literature. With Nottingham Zoo barely recovered from the alphabetic siege, a journalist for the Aberdeen Press and Journal remarked, in a review published on November 8, 1926 about Gertrude Stein’s “The Fifteenth of November”: “Cross-word puzzles are like eating toffee to this stuff”.12 Stein’s story, glossed as “a portrait of T. S. Eliot”, reads, through squinted eyes, like someone shuttling over the rows and columns of a weekly crossword’s clues: “In this case a description. Forward and back weekly. In this case absolutely a question in question. Furnished as meaning supplied.”13 Another humorous critic writing for the Daily Mirror on “Rhymes to Cure the Cold”, that is, on literature as medicine — Longfellow, for instance, gets prescribed to insomniacs — disagrees with the toffee analogy: “Much more modern [medically] and infinitely more powerful in its effects is Gertrude Stein. Up to date disease like cross-word mania can be banished in one dose.”14

Whether an analogue to or cure for the crossword frenzy, Stein’s portrait of Eliot failed to inoculate his work from similar diagnoses. In 1939, a poetry critic at the Birmingham Daily Gazette could not decide if Eliot’s masterpiece was cryptically brilliant or merely an overwrought cryptic: “‘The Wasteland’ may be a great poem; on the other hand it may be just a rather pompous cross-word puzzle”.15 Here again we find a question asked about labour and idleness in this period: are crosswords and difficult poems worth the efforts required to elicit literary pleasure and linguistic revitalisation? Or merely a waste of time?

Ironically — or perhaps felicitously — only two decades after The Times had typecast cruciverbalists as “idlers” chasing their own tails, a bestselling Times crossword compendium included a clue for IDLERS, which T. S. Eliot failed to solve, angrily scoring himself an “X” in the margin:

20. Written by Johnson; edited by Jerome. Unlike bees and ants (6)

Eliot only got as far as the crossing letters, which he correctly reckoned to be.16 He had seemingly forgotten Samuel Johnson’s The Idler (despite having written on Johnson throughout his career), as well as Jerome K. Jerome’s The Idler (despite having been his neighbour in Marlow between 1917–1920), which, alongside a nod to nature’s busiest workers — the classical models of allusion itself — yielded the answer. Eliot’s voracious appetite for puzzles certainly seemed idling (or even addling) to many of his colleagues, who often found him smuggling The Times crossword into “tedious” editorial meetings under the table.17 Undeterred by Ezra Pound’s disdain for such games as “an abomination” in his ABC of Reading (1934), Eliot held the cryptic crossword in enough esteem to consider “finding a reference to myself and my works in The Times crossword” a crowning achievement, aspiring to a rank on the same allusive food chain in which he had chewed, without satisfaction, over Johnson and Jerome.18

Flummoxed by bees and ants, T. S. Eliot nevertheless wound up as a fly. In a strange misdirection of his ambition to an afterlife in the crossword, he is often abbreviated and doubled to clue TSETSE, an African insect known for transmitting insomnia. How apt that the author of The Waste Land, skewered as a “maggot breeding in the corruption of poetry” by F. L. Lucas in 1923, should metamorphose posthumously into a tsetse.19 Eliot’s magnum opus may have struck Lucas as a “toad”, but Eliot actively embraced animal personae throughout his career, not only as the Old Possum behind a Book of Practical Cats (1939), but also as a March Hare in his juvenalia, T. S. Apteryx (a kind of flightless kiwi) in his articles for The Egoist, and familiarly as “the elephant” amongst his co-workers.20 He addressed letters to Ezra Pound with “Dear Rabbit”, and while preparing to publish Marianne Moore’s “The Jerboa” for Faber, wondered if Pound was “maybe not a Rabit at all but a Gerboa a Little Animil wich I understan does illustrate the Quantum Theory by being at two Places at once even if he don’t understand it” [sic].21

In the cryptic crosswords Eliot enjoyed, creatures could indeed behave multiplicitously; like Schrödinger’s Cat (or, indeed, Eliot’s fondness for playing Possum), animals could quantum leap between being alive or dead, vegetable or mineral, real or fictional, rabbit or jerboa. Take, for example, ten randomly sampled clues for CAT or DOG from cryptics in the broadsheets of the last fifty years:

1. Leo caught both sides of argument (3)

2. Best friend rejected god (3)

3. Maybe Lion King not shown in Barrow? (3)

4. Do good as a follower (3)

5. Pet fur has nothing removed (3)

6. Hound party girl initially (3)

7. A natural killer disturbed in the act (3)

8. Shadow boxer, maybe (3)

9. Being crafty, occasionally (3)

10. Perhaps setter ultimately tried to ring (3)

Not one of these clues mentions cats or dogs, yet through the quiet conspiracy of syntactic misbehaviour, all of them yield a precise answer (given in the footnotes).22 They are, and they aren’t, animals. In a 1915 poem, “Portrait of a Lady”, Eliot daydreamed of being footloose from animal taxonomy:

And I must borrow every changing shape

To find expression… dance, dance,

Like a dancing bear,

Cry like a parrot, chatter like an ape.23

The CAT and DOG clues exemplify the expressive opportunities licensed by letting language dance promiscuously between categories. Each clue is straitjacketed by its obligation to solubility, but the endless possibilities of wordplay supply new opportunities to wriggle free. Letters and lookalikes — collaged from idiomatic, sporting, classical, allusive, and glyphic shorthands — form unlikely alliances, aggregated from vocabularies momentarily in dialogue with one another.

In his cutting review of The Waste Land, then, Lucas’ comment that “a poem that has to be explained in notes is not unlike a picture with ‘This is a dog’ inscribed beneath” must have been particularly stinging to Eliot. Not only did it needle his pet preferences (Eliot was firmly team cat), but it also revealed how Lucas misunderstood the pleasure produced by both crosswords and difficult literature, as William Empson implied in a comparison between “obscure puzzles” and “obscure poetry” in The Gathering Storm (1940).24 One poem in Eliot’s Book of Practical Cats seems to claw back at Lucas with its tongue-in-cheek refrain: “Again I must remind you that / A dog’s a dog — A CAT’S A CAT.”25 Unbidden by nominative determinism, the beasts of Eliot’s poetry, personae, and puzzles were under no such obligations, free to hurdle freely across arbitrary Linnean boundaries; free, as it were, to cross-breed.

Torquemada’s Crossbred Bestiaries

The cryptic crossword was still inchoate during the career of Edward Powys Mathers, the English translator and poet, who popularised the difficult form and wrote under the alias Torquemada, after the Spanish inquisitor. His style of puzzle delighted in exploiting the materiality of language to revive words from the inert familiarity into which they had fallen: taking the modernist injunction to “make it new” and defamiliarise deadened language as a principle of radical reassembly, rather than mere refreshment.

Animals real and imaginary, hybrid and crossbred, abound in Torquemada’s puzzles, granted a kind of furtive camouflage amidst the foliage of ambiguity. In a plain crossword, the name of an animal is an endpoint to which the clue must point in a straight line — to extend Lucas’ metaphor, “This is a dog (3)” [DOG] — whereas the cryptic pegs its mischief on wilful misdirection — “This is certainly not a dog (3) [DOG]. The key to a good cryptic, wrote Torquemada, is to make the solver think that they are solving one kind of clue when they are “actually doing nothing of the kind, and you can, for a little, postpone the inevitable end”.26 Delayed gratification, staked on the striptease of ambiguity, staves off instrumentalised meaning, diverting the “inevitable end” both in a temporal and teleological sense. Against the baldness of the American quick style, which Torquemada thought “too easy to hold for long the attention of anyone concerned with and interested in words”, he relished the opportunity to turn words on their heads.27 In doing so, his cryptic grids created all manner of strange beast, becoming little Punnett squares for crossbreeding animals, real and imaginary alike.

It is in a Torquemada grid, indeed, that we come across one of Dr. Seuss’s prized specimens, the Lorax, a full forty years before Dr. Seuss believed he had coined it —“I looked at the drawing board, and that’s what he was!”, or so thought the children’s book author.28

24. With enough beer and bromide and borax

25 & 30. To fill a crustacean’s thorax

27. Any may sheep can be

28 & 31. In a threefold degree

29. Concealed from the fangs of the Lorax

The rules of the puzzle — named “By the Waters of Shannon” (1934) in reference to Edward Lear’s nonsense oeuvre — dictate that “clues consist of one word or consecutive words in each line”.29 Each quintet of five consecutive clues are formatted as a sequence of limericks. The clues are not to be taken at face value. The answers are, in this stanza, ALE, PEREOIN, EWE, TREBLE, and HID, masked synonymously amid the continuous verse. The solver poses as a literary critic, performing a caricature of close reading to unlock a secret. It cannot be claimed definitively that Seuss magpied Torquemada’s cryptid — though, suggestively, he studied at Oxford during the peak of Torquemada’s popularity — but it is intriguing that two writers in the service of silliness would invest a fictional animal with the same name.

Animals have always held a certain reverence in the crossword. In the late composer Stephen Sondheim’s guide to the British cryptic for American readers, he caricatures quick crosswords in The Daily News and the New York Times as requiring knowledge of the “Bantu hartebeest” (the KONGONI, an African antelope).30 Grids are crowded with the ASP, EFT, ELAND, GNU, IBEX, NYALA, OKAPI, and XENURUS: animals that have obtained a peculiar hyperreality in the public consciousness, appearing in crosswords more often than in conversation. A 1934 letter from P. G. Wodehouse even credits a crossword setter with “putting the good old emu back into circulation”, embalmed in the rag-tag bestiary of the newsprint puzzle, where the unique character of an animal is, ultimately, subordinate to its unique, alphabetic characters.31 Torquemada, on the other hand, themed many of his experiments around the shapes of animals, preserving their bodies as well as their names — as Vladimir Nabokov had done in a 1926 letter to Véra, which contained a puzzle that looked like a butterfly.

Only two years after the critic Louis Untermeyer slammed writers including T. S. Eliot and James Joyce for being part of the “crossword-puzzle-school”, Torquemada’s Cross-Words in Rhyme for Those of Riper Years (1925) pioneered the verse puzzle, where every single clue is formatted as a metrically regular rhyming couplet.32 Each grid in Cross-Words in Rhyme is designed as a kind of concrete poem, where the lattice of solutions — disparate words drawn into surprising compatibility — forms an (often animal) image. “The Swan” begins self-referentially by telling the solver “I am the cross-word setter’s base device / For making non-existent words suffice” (ANAGRAM).33 Later in the grid Torquemada remixes a nursery rhyme to clue a short word:

29. As hours in days, so many merulae

Found living tombs in me, but did not die.34

Knowing that “merulae” refers to blackbirds is certainly tricky, but the sing-song cadence of the couplet brings to life its solution, PIE, based on “Four-and-Twenty Blackbirds”. The birds are alive, entombed inside a pie; paradoxically, the pie is alive, entombed inside the image of a swan. The crossword apparatus, like George Steiner’s archetypal poet, is constitutionally “a neologist, a recombinant wordsmith. . . a passionate resuscitator of buried or spectral words”.35 Bird inside pie, pie inside bird: both are “encrypted” (etymologically referring to burial) by the setter, and resurrected by the attention of the solver.

The entangled difficulties of the cryptic crossword, then, provided a uniquely vital opportunity for defamiliarising language: for reheating, as it were, Bushmiller’s alphabet soup, and letting the animals run rampant. Whether “breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land”, as in The Waste Land, or breeding bird-pie fractals, the experimental aspects of literary modernism found extreme expression in cryptics, which took literature and letters alike as their raw materials. In his Puzzle Book (1934), Torquemada gave as his exemplar clue “I made self into poet” (MASEFIELD, a British poet whose surname recombines the letters in “I made self”), achieving anagrammatically the very metamorphosis trumpeted by the clue.36 Combinatorial, cleverly arranged letters could disclose portals into surprising realities. In this regard, Torquemada owed a great deal to the language games waged in the nonsense literature of the nineteenth century, which, in turn, also influenced modernist poetry, namely Eliot’s more-playful verse.

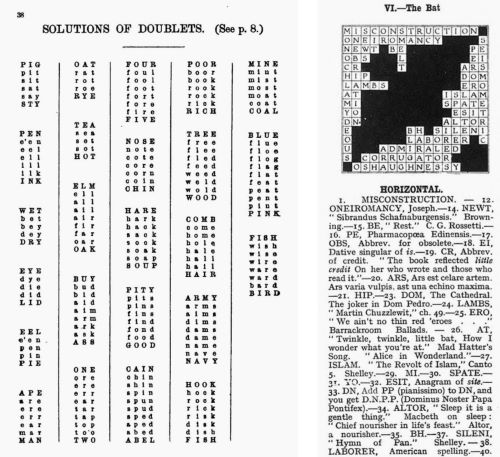

Lewis Carroll’s Doublets (ca. 1879) demanded a similarly interactive hand in making evolution come to life, turning APE into MAN, or FISH into BIRD by morphological increments, as if speeding up Darwinian selection to the pace of handwriting.37 If, as Eliot put it, nonsense literature employed “a parody of sense” rather than “a vacuity of sense”, then Torquemada took this sideways slant to its fullest extent.38 In “The Bat”, he apes Carroll: “What he was me, that black thing in the middle, / A hatter once confessed to be a riddle”. The solution, AT, as Torquemada explains, refers to the Mad Hatter asking “Twinkle, twinkle, little bat, / How I wonder what you’re at” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), with “that black thing in the middle” singling out the zoomorphic, batty cavity in the heart of the grid itself.

Broken Knowledge and Aphoristic Grace

In a moving obituary for Torquemada, written by his widow Rosamond Mathers, she recalls his habit for overwriting inert objects with a certain personality: “All the things he ordinarily used were apt to take on the qualities of toys; he had a happy way of naming all the common household objects so that each had its temperament, predominantly mischievous or benevolent”.39 Torquemada, we are told, was not content with things staying in their lanes, and preferred to be “confronted by a haphazard collection of words” than a neat one when he plotted his puzzles. She remembers him “drawing marginal decorations in vari-coloured chalks while he broods on some uninspiring word”, a behaviour that would ultimately be reciprocated by his legion solvers, including J. R. R. Tolkien, whose crossword doodles were recently exhibited by the Bodleian Library.

While going through his more than thirty thousand clues for The Observer in preparation for the posthumous publication of Torquemada: 112 Best Crossword Puzzles (1942), Mathers was astonished to find singular words “cropping up fifty times and more” without replicated wordplay: “it was astonishing how he varied the clue”, she notes, remarking on his gift for “using words in a sense remote from the intention from their author”.40 The epigraph to Cross-Words for Riper Years exemplifies the latter trait, cheekily recontextualising a line attributed to “Anne Wordsworth” for comic effect: “Children, remember each Cross Word / Is written in a dread unearthly Book”. The same is true of his prevailing fondness for animals. When Torquemada was not structuring grids around animals, or penning clues which secretly hatched them, he would enlist their help in all manner of games. “Product of a noise many associated with lobster” yields MAYONNAISE (an anagrammatical “product” of “a noise many”), while “Sound of embrace a crocodile in secret” gave HUGGERMUGGER (a homophone for “hug a mugger”, making use of “crocodile” in slang).41

Reducing the appeal of a word game to a few words is almost self-defeating, but Sondheim came close when he said the British cryptic combined “literary cleverness, humour, even a pseudo-aphoristic grace”.42 Sondheim’s compound adjective refractures an aphoristic mode that, to Francis Bacon, was already “a broken knowledge, inviting men to inquire further”.43 Torquemada’s cryptics implored their solvers to participate in unfamiliarity: to join a collaborative meaning-making based not only on close reading, but in turn, close writing and close arithmetic, where even the most unremarkable words can be seen anew. Sondheim’s antelope may have remained a KONGONI in the “bald clues” of the United States, but uncaged by the cryptic style he favoured, it could flee into whimsical free association with its lexical neighbours; it could, as it were, elope with the ants that escaped T. S. Eliot.

When it came to the affinity between the modernist puzzle and the modernist poem, Torquemada didn’t mince his words. Or, rather, he minced his words very selectively to make the same point: “In shape nothing more than a poet”. The solution is OVOID, a “shape” generated by adding “nothing” (O) to “a poet” (OVID). Torquemada performs a miniaturised Metamorphoses, reconstituting a literary object, and hatching a new adjective most commonly used to describe eggs, and thereby regeneration itself. The clue is alive with association, and nudges the distractible imagination of the solver one way, while its surface inconspicuously leads elsewhere. The attention nurtured by wordplay, a device for defamiliarity based on the bizarre contingencies embedded in language, leavens the word and world alike with surprising potential. Dispensing penny-drop-moments like arcade coin pushers, the best clues reward a reader not with anything empirically valuable, but instead with the giddy excitement of watching words build up, build up, and topple into surprising new riches.

Postscript44

1. Doublespeak in accord protecting large union (9)

2. Editing out lines, Lamb guilty over current vagueness (9)

3. Imprecision by a doctor, one responsible for cutting trainee (9)

4. Uncertainty after my BA and TUI flights essentially exploded (9)

5. Occasionally calm, B. B. King quaintly produces doubtful tone (9)

6. In the morning, chap who goes both ways welcomes sex with mysterious character (9)

7. Postgraduate rebuffed extensive university computer support with variable confusion (9)

Appendix

Endnotes

- “Ostrich Policeman”, Nottingham Evening Post, 14518 (January 2, 1925), 4.

- “Fugitive Monkey”, Nottingham Evening Post, 14540 (January 26, 1925), 7.

- “Posers for the Zoo”, Nottingham Evening Post, 14531 (January 17, 1925), 5.

- Ernie Bushmiller, “Cross Word Cal”, Sunday New World (May 3, 1925).

- “Cross-Word Puzzles: An Enslaved America”, The Times (February 21, 1925), 4.

- “An Enslaved America”, Tamworth Herald (December 27, 1924), 7.

- “Library Dictionaries Damaged”, Gloucester Citizen, 50.44 (February 20, 1925), 8.

- “The Cross-Word Vogue”, Western Daily Press, 133.22758 (December 31, 1924), 5.

- “A Familiar Form of Madness”, New York Times (November 17, 1924).

- See: https://whatsnewinpublishing.com/400000-people-now-subscribe-to-nyts-digital-crossword

- “Cross-Word Puzzles: An Enslaved America”, The Times (February 21, 1925), 4.

- “Georgian Stories”, Aberdeen Press and Journal (November 8, 1926), 2.

- Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (New York: The Literary Guild, 1933), 247. The “Fifteenth of November” appears under the title “A Description of the Fifteenth of November: A Portrait of T. S Eliot” in Modernism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 405.

- “Here and There”, Daily Mirror (May 6, 1933), 6.

- “Modern Authors and the Plain Man”, Birmingham Gazette (October 20, 1932), 4.

- Annotation from “T. S. Eliot’s Crossword Puzzles”, T. S. Eliot Foundation (March 10, 2017), available online at: https://tseliot.com/foundation/t-s-eliots-crossword-puzzles.

- Peter du Sautoy, “T. S. Eliot: Personal Reminiscences”, in The Southern Review 21.4 (October 1, 1985), 947.

- Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading (London: George Routledge, 1934), 95; Eliot, letter to Sydney Castle Roberts (November 1958).

- F. L. Lucas, review of The Waste Land, in New Statesman (November 3, 1923).

- For a full list of Eliot’s animal personae, see Emily Essert, “Cats, Apes, and Crabs: T. S. Eliot among the Animals”, in Representing the Modern Animal in Culture, eds. Jeanne Dubino, Ziba Rashidian, and Andrew Smyth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 119–136 (119).

- Letter from Eliot to Pound (July 1934), quoted in Hugh Haughton, “The Possum and the Salamander: T. S. Eliot and Marianne Moore”, in The Poetry Society 110.2 (Summer 2020).

- 1. CAT = “Leo”, C (“caught” in cricket) + AT (both sides of A[rgumen]T) 2. DOG = “Best friend”, GOD backwards (“rejected”) 3. CAT = “Maybe Lion”, R (King, the regnal abbreviation of rex) taken out of CART (“barrow”) 4. DOG = “a follower”, DO + G (standard abbreviation for “good”) 5. CAT = “Pet”, COAT (“fur”) without O (“nothing removed”) 6. DOG = “Hound”, DO (“party”) + G (“girl initially”) 7. CAT = “A natural killer”, an anagram (“disturbed”) of ACT 8. DOG, twice defined: “shadow” (as a verb) and “boxer” (as a breed) 9. CAT = “Being”, the occasional letters of C[r]A[f]T[y] 10. DOG = “Perhaps setter”, the ultimate letters of [trie]D [t]O [rin[G]. Clues sourced from a reverse search on: https://wordplays.com/crossword-clues.

- Eliot, “Portrait of a Lady”, Others: A Magazine of the New Verse (September, 1915).

- William Empson, The Gathering Storm (London: Faber and Faber, 1940), 55.

- T. S. Eliot, “The Ad-Dressing of Cats” in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (London: Faber, 2001), 45.

- Torquemada, The Torquemada Puzzle Book (London: Victor Gollancz, 1934), 14.

- Torquemada, 11.

- Donald E. Pease, Theodor Geisel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 139.

- Torquemada, “Puzzle 239”, in 112 Best Crossword Puzzles, ed. J. M. Campbell (London: Pushkin Press, 1942), 181.

- Stephen Sondheim, “How to do a Real Crossword Puzzle”, in New York Magazine (April 8, 1968), 11.

- Quoted in Alan Connor, Two Girls, One on Each Knee (London: Penguin, 2014), 6.

- Louis Untermeyer, American Poetry Since 1900 (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1923), 153. Consider, for instance, the clue “By means of argot I will make you think; / I also turn a lemon into drink”. The couplet neatly stratifies the solution (ADE) into two pathways: George Ade published Fables in Slang (“argot”) in 1899, but if the reference went over your head, you can deduce that adding “-ade” to “lemon” creates “lemonade”. Each approach, hierarchised, is placed into imaginative parity by the rhyme connecting them. The entire clue is premised on the idiom of transformative opportunity — “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade” (first used in 1915) — and thereby glosses the riddle with a sense of its own invigorating power. This puzzle can be found in Torquemada, Cross-Words in Rhyme for those of Riper Years (London: Routledge and Sons, 1925), 22.

- Torquemada, “The Swan”, in Cross-Words in Rhyme, 10.

- Torquemada, 11.

- George Steiner, “On Difficulty”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 36.3 (Spring, 1978), 263–276 (264).

- Torquemada, Puzzle, 13.

- Lewis Carroll, Doublets, a Word-Puzzle (London: Macmillan, 1879), 38.

- Eliot, “The Music of Poetry”, in Selected Prose, ed. John Hayward (London: Penguin, 1953), 57.

- Rosamond Mathers, “Torquemada”, in Torquemada: 112 Best Crossword Puzzles, 9–11.

- Mathers, 12.

- Torquemada, “Puzzle No. 564” (1937), in 112 Best Crossword Puzzles, 212; “Puzzle No. 319”, 84.

- Sondheim, “How to do a Real Crossword Puzzle”, 11.

- Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning, ed. Henry Morley (London: Cassell, 1893), 332.

- My own clues, inspired by William Empson, Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), generated by manipulating his The Structure of Complex Words (1951). [1. AMBIGUITY (“doublespeak”) = AMITY (“accord”) around BIG U (“large union”) 2. AMBIGUITY (“vagueness”) = [l]AMB GUI[l]TY (“editing out lines”), over I (“current”) 3. AMBIGUITY (“imprecision”) = A MB (“a doctor”) I (“one”) GUITY (“responsible for cutting trainee”, “guilty” minus “l[earner]”) 4. AMBIGUITY (“uncertainty”) = anagram (“collapsed”) of MY BA TUI [fli]G[hts] (“flights essentially”) 5. AMBIGUITY (“doubtful tone”) = the occasional letters of [c]A[l]M [b] B [k]I[n]G [q]U[a]I[n]T[l]Y 6. AMBIGUITY (‘“mysterious character”) = AM (“in the morning”) BI GUY (“chap who goes both ways”) welcoming IT (“sex”) 7. AMBIGUITY (“confusion”) = AM (“postgraduate rebuffed”, MA backwards) BIG (“extensive”) U (“university”) IT (“computer support”) Y (“variable”)].

Public Domain Works

- Doublets: A Word-Puzzle, Lewis Carroll (1879)

- The Advancement of Learning, Francis Bacon (1893)

- “Portrait of a Lady”, Appearing in Others: A Magazine of the New Verse (1915)

- American Poetry Since 1900, Louis Untermeyer (1923)

- The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot (1922)

- Cross-Words in Rhyme for those of Riper Years, Torquemada (1925)

- Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, T.S. Eliot (1939)

Further Reading

- Two Girls, One on Each Knee: The Puzzling, Playful World of the Crossword, by Alan Connor

- Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, by Adrienne Raphel

- Eliot’s Animals, by Marianne Thormählen