The origins of the Board ran through Sam Rayburn’s mentor, fellow Texan John Garner, and Garner’s predecessor in the Speaker’s chair, Nicholas Longworth.

Introduction

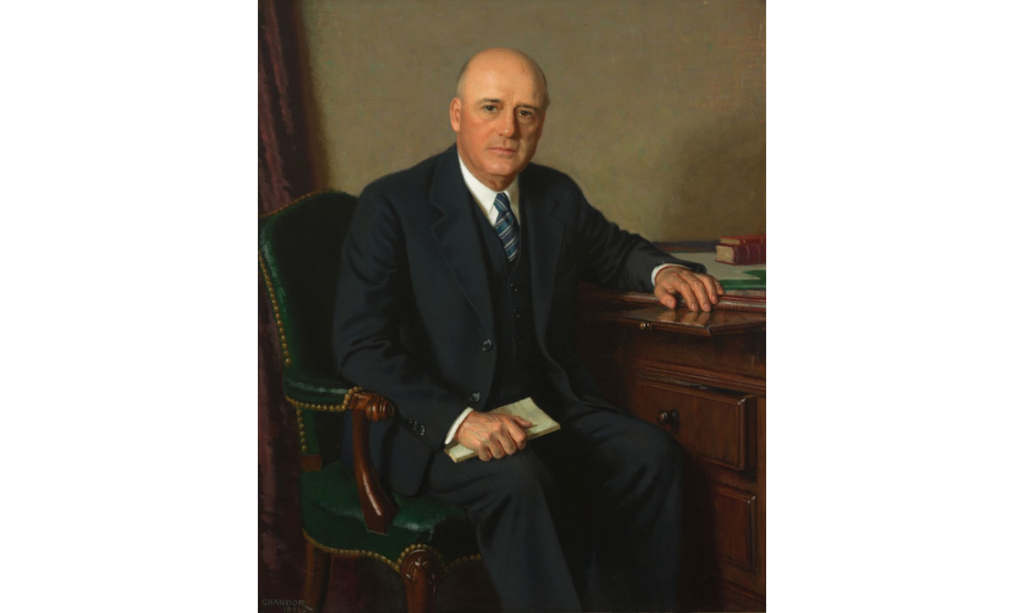

Board of Education. Doghouse. Cabinet Room. Sanctum sanctorum. Or, as Speaker Sam Rayburn modestly called his tiny hideaway where informal legislating happened, “the little room.” Despite changing hands, names, and even location, the spirit of the room remained the same. From its beginnings during Prohibition, it was a place where information, political horse trading, and liquid refreshment flowed. The origins of the Board run through Rayburn’s mentor, fellow Texan John Garner, and Garner’s predecessor in the Speaker’s chair, Nicholas Longworth.

Cabinet Room

Before either became Speaker, Longworth and Garner were fast friends, and together they established the potent mix of libation and legislation that became the raison d’etre of the Board of Education. Longworth was urbane and Garner was countrified, but they shared conviviality and an honest regard for each other.

Garner secured an unused office just steps from his room in the House Office Building (likely in what is now Room 315 of the Cannon House Office Building), dubbing it “The Cabinet Room” around 1920. Just like hundreds of other Representatives’ offices, a desk, chairs, table, and a little sink in the corner were the spartan furnishings. In the Cabinet Room, however, the desktop rolled open to reveal a supply of bourbon for the Democratic colleagues who met there during Prohibition, often to flip through Texas newspapers and to discuss politics.

Garner made frequent visitor—and Republican—Longworth an honorary member of the club, and the two cemented their friendship. As they climbed the leadership ladder, their social obligations outgrew the Cabinet Room and drained the roll-top’s stash. In 1924, Longworth, as the Majority Leader, gained access to Capitol hermitages. It was whispered that the pair relocated their joint establishment to a private retreat there, the “sanctum sanctorum.”

Bureau of Education

Longworth and Garner’s shared clubhouse, down a narrow corridor off the Capitol Rotunda, was decidedly a step up from the Cabinet Room, but the activities were the same: “communicating views and lubricating the legislative machinery” with both Representatives and select journalists, according to fellow Texan Ovie Clark Fisher. An appreciative John McDuffie of Alabama dubbed it the “Bureau of Education.” Garner agreed with the sentiment, explaining later that “you get a couple of drinks in the young congressman and then you know what he knows and what he can do.”

Meetings in the Bureau of Education were almost a ritual once Longworth became Speaker and Garner rose to Minority Leader. In the late afternoon, as the House wound up its work, Garner strolled to the rear of the Chamber, and signaled Longworth, who adjourned the House. They repaired to the Bureau to “strike a blow for liberty,” as Garner put it: to have a drink in the days of Prohibition. Each of the regulars provided his own bottle, secreted in a bookcase. It was ostensibly Longworth’s room, and he equipped it with an icebox for seltzer water. Garner had no use for carbonated water, preferring it straight from the tap.

The two leaders often used the Bureau to work out legislative wrinkles. They and their lieutenants discussed the floor agenda, heard proponents pitch important bills, explored lines of disagreement, sped up programs, and crafted tentative agreements. One day in the 1920s, reporter Bascom Timmons wandered by and asked Garner what was the latest news from the Bureau. “Oh, the Republicans have cooked up another nefarious scheme,” the Democratic Leader chuckled, “and I am going to try to talk Nick out of it and save the people a few of their liberties.”

The House’s two leaders used the sanctuary jointly until Longworth’s death in April 1931. The 1930 elections had left the House closely divided and a number of special elections in the intervening year swung the narrow majority to the Democrats, making Garner the new Speaker when the 72nd Congress convened in December 1931. With his negotiating partner gone, the new Speaker made the space a gathering place primarily for Democrats.

The Doghouse

During Garner’s Speakership, he used his formal office for ceremonial work, the Bureau of Education for maneuvering, and a third room for the long days and hard work of running the House. Ettie Garner, the Speaker’s wife and trusted advisor, set up operations in Room H-128, a little first-floor hideout filled with murals from its days as the Territories Committee room. A vital force and capable administrator throughout Garner’s career, she ran the Speaker’s Office from there, directing the staff upstairs in the formal office and managing correspondence and constituent issues. When Garner became Franklin Roosevelt’s Vice President in 1933, he considered the Bureau of Education so integral to his work on Capitol Hill that he immediately reconstituted it in the Senate Office Building until he obtained a better spot, an obscure room in the Capitol’s old Supreme Court offices. Senator Nate Bachman gave it the inglorious title of the Doghouse, and colleagues knew that New Deal legislation was explained, pressed, and managed from there. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins was such a frequent collaborator that her meetings there became a regular note in newspaper columns.

Board of Education

Meanwhile, Ettie Garner’s former stronghold on the House side was ready to become an informal legislation center itself. In 1936, Sam Rayburn, now Majority Leader, wheedled the keys from Speaker William Bankhead and set up his version of the Bureau, by now called the Board of Education. While Garner was a progenitor of the Board of Education and its many uses, long-serving Rayburn became its most famous denizen. He used H-128 as a power center for 25 years, with such success that even in the 21st century the room continues to be called the Board of Education.

H-128 is small by Capitol standards. But Rayburn—who ascended to the Speakership in 1940—made it a comfortable space. Old leather-buttoned chairs and sofas, a shabby rug, and a time-worn desk were the homey furnishings. A veneer box at one end hid a refrigerator, refilled each day with ice and seltzer water, and a telephone table was shoved into the window well. At one end of the room, two flags—for Texas and the United States—stood in stanchions below a rare bit of ostentation, the Texas state seal that Rayburn had painted amid the other murals on the walls. Prohibition was long past, but the traditions of the Board of Education were strong. The Speaker’s big desk drawers opened to reveal bottles of bourbon and Scotch.

Powerful House Democrats gathered at the end of a wearying day to collapse on the sofa, play bridge, and trade information. A few reporters and Senators were invited to join in, particularly Speaker Rayburn’s former protégé Lyndon Baines Johnson, who claimed to be one of the few with a key to the room. Another Senator, Harry Truman, continued to visit the Board of Education even after he became Roosevelt’s Vice President in 1945. One night that spring, the phone in the window well rang just as Truman poured himself a drink. The switchboard had tracked him down and relayed the message that he was needed at the White House immediately. Rayburn immediately divined that the President had died, and before Truman called to say he would not be back for his bourbon, the Speaker had begun to write an official statement for the press. It became the most recollected moment in Board of Education history, but the room’s real importance, and that of its predecessors, was in the everyday camaraderie and the informal schooling in the arts of politicking practiced by Longworth, Garner, Rayburn, and the scores of acolytes who studied there.

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 06.18.2018, to the public domain.