Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity and the beliefs and practices of prehistory.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

“But for man, no rest and no ending. He must go on, conquest beyond conquest. First this little planet and all its winds and ways, and then all the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him, and, at last, out across immensity to the stars. And when he has conquered all the deeps of space, and all the mysteries of time, still he will be beginning.”

H.G. Wells, 1936

Opening Genesis

This elongated initial letter and bold rendering of “In the Beginning” in red ink make this one of the most powerful and evocative titlepages in printing history. T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, the founder of the Doves Press, commissioned Edward Johnston to design the first page of this typographical masterpiece. The Doves Press Bible is one of the monuments of the Arts and Craft Movement that swept Great Britain and America at the end of the nineteenth century.

Mandala of Auspicious Beginnings

This is the first mandala in a set of 139 that were painted in the nineteenth century to serve as aids to a compilation of Mahayana Buddhist teachings. In Mahayana Buddhism, the ideal is the Bodhisattva, one who has taken the vow to become a Buddha, an enlightened one. The mandala, a symbol of the universe in Buddhist cultures, depicts the three great Bodhisattvas who represent the power, wisdom, and compassion of the Buddhas. This mandala was placed first in the collection to invoke the blessings of the Bodhisattvas, and serve as a dedication to the entire collection.

The Origins of Taoism

Taoism is one of the earliest religions in the world and derives from the worship of nature. Established during the Dong Han Dynasty (25-220) in China, it has influenced all aspects of Chinese society for 1800years. The “eight immortals” is the most famous folktale of Chinese Taoism. This rare scroll depicts many events including the eight immortals’ battle with the Dragon King of the Ocean, shown here. In order to tame the dragon, the eight immortals use their super powers to move the soil of the great mountain of the east, to fill the ocean.

The Koran’s First Chapter

This nineteenth-century hand-copied Koran in Arabic is open to the Fatiha, the opening chapter of Islam’s holy book. In seven very short verses, the Fatiha sums up man’s relation to God in prayer.

The first verse “In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful” is said out loud by Muslims at the beginning of every major action they undertake each day: before a prayer, before a meal, before work, before travel, before a public speech, and so forth. It is one of the most important phrases in the Arabic language.

Creation Accounts and Depictions

“Earth with its mountains, rivers and seas, Sky with its sun, moon and stars: in the beginning all these were one, and the one was Chaos. Nothing had taken shape, all was a dark swirling confusion, over and under, round and round. For countless ages this was the way of the universe, unformed and illumined, until from the midst of Chaos came P’an Ku….[H]e raised his great arm and struck out blindly in the face of the murk, and with one great crashing blow he scattered the elements of Chaos.”

“Heaven and Earth and Man” Chinese Myths and Fantasies, 1996

The Opening Word of the Bible

The Hebrew word Beresheet, which means “in the beginning,” opens the Book of Genesis. This decorated initial word is from the first volume of a planned multi-volume edition of the Hebrew Bible. The volume was published by the Society of Jewish Bibliophiles, the Soncino Gesellschaft, in Germany in 1933. Hitler’s rise to power prevented the Society from completing what would have been the first bibliophilic edition of the Hebrew Scriptures.

Celebrating First Moon Orbit

This book is one of 100 copies printed at a New Jersey monastery to commemorate Apollo 8, the first manned mission to the Moon. The spacecraft entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve,1968. That evening, the astronauts did a live television broadcast, in which they showed pictures of the earth and moon as seen from Apollo 8. They ended the broadcast by reading from the first chapter of Genesis and with a prayer by mission commander Frank Borman. The verses from Genesis and the prayer are the text of this book. The illustrations are watercolors hand-painted over photographs taken on the expedition.

A Poet’s Version of Creation

“The Creation” is one of seven poems in God’s Trombones through which African American poet James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) paid tribute to the black preachers he remembered from childhood. Each free-verse poem presents in lyrical but colloquial language a version of a classic sermon, such as “The Creation” or “Noah Built an Ark.” Johnson rejected the use of broad Negro dialect as comic and derogatory and revealed the old-time black preacher as a folk hero of dignity and eloquence.

Creation out of Chaos

“In the beginning (if there was such a thing), God created Newton’s laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces. This is all; everything beyond this follows from the development of appropriate mathematical methods by means of deduction.”

Albert Einstein, 1949

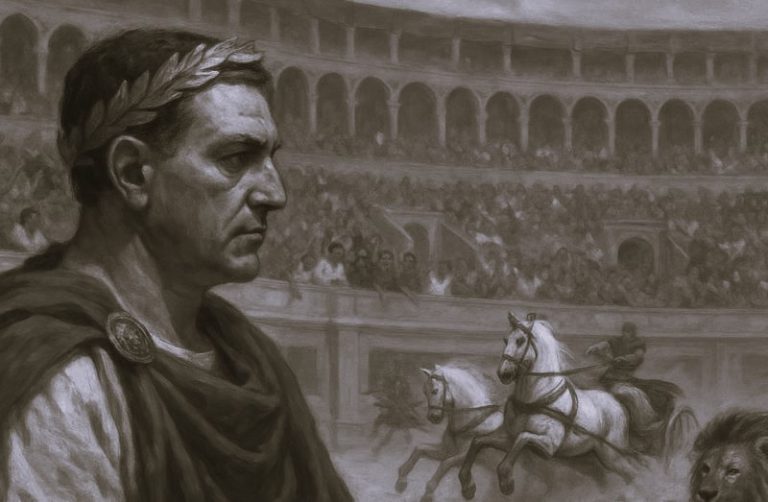

The Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C.-17 A.D.), in his Metamorphoses, elaborated an account of cosmic beginnings—the creation of the world out of chaos—that had obvious affinities with both Hebrew and Greek explanatory traditions. Questions of origins were especially topical during Ovid’s time when Rome was transforming itself from a republic into an empire. The edition of the Metamorphoses on the left, accompanied by engravings and translated into French, was published in Paris in 1661.

The edition of the Metamorphoses above was published in Lyon in 1557.

The edition above was accompanied by engravings by Niccolo Agostini. It was translated into Italian and published in Venice in 1538.

Vishnu Resting

In Hinduism, Vishnu is the deity responsible for maintaining the universe once created. The entire universe is periodically destroyed by fire and dissolved for a time into an infinite ocean. Vishnu rests upon this ocean until it is time for the universe to be re-emanated. In this illustration the god rests on the serpent Shesha, whose other function is to hold up the world. Vishnu is attended by his wife, Lakshmi, and the monkey-faced sage Narada. Brahma, the deity responsible for beginning the world in each cycle, rests on a lotus coming out of Vishnu’s navel.

Dialogues of Creation

This woodcut illustrates the first edition of Dialogus Creaturarum (Dialogues of Creation), a popular fifteenth-century collection of creation stories. Composed as fables using the sun, moon, stars, fish, birds and animals as characters, the moral tales are presented in 123 dialogues. The book was noteworthy for the imaginative way in which the fables were told and for the accompanying woodcuts characterized by clever depictions, natural flowing lines, and a sense of humor. Throughout the work the anonymous woodcut artist combined elements of the fables into his design so the stories could be understood even by those who were unable to read the text.

The Balinese Cosmos

This work by the important Balinese painter Togog (ca. 1915-1989) depicts the Balinese conception of the cosmos while reflecting the emphasis on balance in that culture. In Balinese cosmology, the World Serpent (Antaboga) created the World Turtle (Bedawang) through meditation. On the turtle are coiled two snakes; this is the foundation of the world. This painting, also a design for a funeral pall, depicts the turtle and snakes, with the Supreme Being above.

Yoruba Creation Legend

At one time, professional storytellers in Africa collected and told the stories of their day and of past times. This oral tradition has preserved the story of the Yoruba people of West Africa who regard the city of Ife as their place of origin and, according to Yoruba mythology, as the site of earth’s creation. This poem retells the ancient story of the creation of Yoruba and features Olodumare, the Lord of Heaven and the Creator, and Orisanla, deities in the Yoruba pantheon of gods.

God’s Hand in the Creation

Called the Nuremberg Chronicle by modern day historians, this book is considered one of the most important histories published in the fifteenth century. Illustrated with more than 1800 woodcuts, Schedel’s work tells the story of mankind from the creation of the world to the end of the Middle Ages. The woodcut displayed here illustrates the fourth day when God created light–the greater light to rule the day, the lesser light to rule the night, and the stars to divide the light from darkness.

Haydn’s The Creation

In 1796 Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809), by then the most famous composer in Europe, began work on what he would regard as his masterpiece–The Creation, with a libretto based on the biblical account of creation as well as passages from John Milton’s Paradise Lost. First performed in 1798, it was an immediate and unprecedented success. This first edition orchestral score was privately published, sponsored by friends and admirers of the composer.

Blake’s Image of the Creation

William Blake’s (1757-1827) image of the creation is one of the most enduring ever conceived. In it he depicts the monumental figure of the creator set within the framework of the blazing sun and by the use of the set of huge calipers (a measuring instrument) incorporates the concept of rationality in what was about to be wrought. This relief etching is further enhanced by Blake’s brilliant application of color, which heightens the drama of the story of the beginning of the world.

Image from The Song of Los

The archetype of the “creator” is a familiar image in the illuminated books of William Blake. At left, Blake depicts an almighty creator stooped in prayer contemplating the world he has forged. The Song of Los is the third in a series of illuminated books, hand-painted by Blake and his wife, known as the “Continental Prophecies,” considered by most critics to contain some of Blake’s most powerful imagery. Only six copies of The Song of Los are known to exist. This copy is the most brilliantly colored version and is continually consulted by scholars studying Blake’s work.

In the right-hand image, Los resting on a cloud, leans on his hammer, the symbol of his creative energy. He stares down at the bright red sun that he has fashioned out of components of his own soul. The sun represents the giver of life, that most fundamental of elements which keeps the world in balance and nurtures the development of all physical matter.

Kalevala Cosmology

The Finnish epic, the Kalevala, tells the story of the creation. This opening shows Ilmatar, maiden daughter of Air, lying lonely in the sea. A golden-eyed duck builds a nest on her knee and lays eggs, which fall and break to pieces, forming the earth, the heavens, the sun, the moon, stars, and the clouds. Compiled from Finnish folk poems in the mid-nineteenth century, this epic was important for fostering Finnish nationalism under Russian rule. This copy is an Italian edition in the Library’s Russian Imperial Collection.

Santal Creation Account

The Santals are a numerous tribal people living in several states in eastern India. Among them live itinerant Hindu professional storytellers and painters (jadupatuas), who recount Santal stories, religious beliefs, and festivals using narrative scrolls that they paint. This recently acquired scroll shows the Santal creation story. In the top panel are the three principal Santal deities, Maran Buru, Jaher Era, and Sin Cando. In the next are the water and water creatures made by the creator, Thakur (“the Lord”). From the mating of two geese come the first human couple and from them their seven sons and daughters, who marry each other and then divide into clans so that siblings may no longer marry each other.

Finnish National Epic

This opening depicts the creation goddess as a young girl celebrating her attributes of air and light. The best-loved illustrations of the epic are by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931), and this special edition includes twenty-four illustrations of his paintings. Compiled by Elias Lonnrot (1802-1884) from Finnish folk poems, the Kalevala advanced the cause of Finnish nationalism.

A Cosmogonic Hymn

The earliest and most basic of the Hindu scriptures is the Rgveda, usually dated to about 1500 B.C. This hymn tells of an original male (purusa) of a thousand heads, eyes, and feet, which the gods cut up to produce the world. This volume is the first complete printed version and the first complete critical edition of the Rgveda, by the German-English scholar Friedrich Max Müller (1823-1900).

Stories of the Creation of Japan

This book is one of a three-volume set of Japanese mythology containing stories of the creation of Japan. This volume tells the story of the two deities–the male Izanagi and the female Izanami–who descend from heaven and create the islands of Japan through their marital union. Eventually Izanagi produces the Sun Goddess (Amaterasu Omikami), whose descendants are said to rule Japan.

First Human Beings

“So passed they naked on, nor shund the sight of God or Angel, for they thought no ill:

John Milton, Paradise Lost, 1667

So hand in hand they passed, the lovliest pair that ever since in loves imbraces met,

ADAM the goodliest man of men since borne His Sons, the fairest of her Daughters EVE.”

Mixtec Indians Creation

In this manuscript that predates the Spanish Conquest, the Mixtec Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico, illustrate how their gods created the world. According to their cosmology, the first humans were the Primordial Twins. One Deer, shown here with magic incense copal and ground tobacco, created the Mother and the Father of the Gods. Mother and Father then made four men and an entire constellation of spirits for crops, fire, smoke, forests, and other aspects of nature and the world.

Pangu Creates the World

According to Chinese mythology, a giant called Pangu used his own body to create the world. Before creation, Pangu was like an egg yolk inside an egg. After eighteen thousand years, the world began to open. The light air called “Yangqi” flew up and became sky, and the heavy and wet air called “Yinqi” sank down and became earth. When Pangu breathed, his breath became wind. When he cried, his tears became oceans and rivers. After many years, Pangu died, and his head, body, and limbs turned into five famous mountains in China.

Nüwo Creates a Perfect World

According to Chinese mythology, a giant called Pangu created the world, but left imperfections. Because the sky was tilted at the northwest corner, the sun, moon, and other celestial bodies were not in harmonious order. The earth was lopsided because Pangu did not fill the southeast corner, causing the oceans, lakes, and rivers to pour in one direction. Nüwo, the Goddess of Creation, fixed these mistakes and then used mud to make men and women. This image of Nüwo is from a tenth-century stone carving in the famous cave complex at Dunhuang in Chinese Central Asia. The work reflects the influence of Indian art, a result of cultural exchange along the “Silk Road,” a trade route linking Japan with the Mediterranean.

“Jwok (an androgynous god) had sons–first, an elephant; then, a buffalo, a lion, a crocodile, after that a little dog; and finally, man and woman. All this took place in a far country. The name of the first man was Otino. The name of the first woman was Akongo.”

Sheikh Oterie of Dimma (a member of the Anuak tribe of Sudan), 1990

German Renaissance Master

Artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) engraved this image of the biblical first humans whose creation and fall from God’s favor are recounted in Genesis. Dürer’s woodcuts and engravings were at the forefront of the information revolution that swept through Renaissance Europe, placing printed texts and images in the hands of an increasingly literate populace. The iconography here is loaded with meaning, including the rabbit, cat, ox, and elk symbolizing the four temperaments of humankind: sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic, and melancholic.

Adam and Eve by Dürer

German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) earned widespread fame during his own time and is one of the monumental figures in the history of Western printmaking. From his early twenties until his death at the age of fifty-seven, Dürer worked on at least six different versions of Christ’s Passion–the story of Christ’s suffering between the Last Supper and the Crucifixion. This image of Adam and Eve being driven out of Paradise at sword point is from his Small Passion, which contains thirty-six episodes from the Bible. Despite its small scale, the dynamic composition of the work gives it a powerful visual and narrative force.

German Renaissance Image of Biblical First Humans

Lucas Cranach, the Elder (1472-1553), created this woodcut image depicting the biblical first humans. The Reformation and humanist learning were key catalysts in the information revolution of sixteenth century Germany, and Cranach himself was a personal friend and advocate of Martin Luther.

The Creation of Eve

This book represents the first American appearance of twenty-five woodcuts designed by the noted English artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1896). Originally commissioned by William Morris (1834-1896) for an edition of the Bible he planned to publish, these images capture for the modern reader the events during the creation of the world as described in the book of Genesis including the creation of the first woman, Eve. This work was printed by Daniel Berkeley Updike, founder of the Merrymount Press, in an edition of only 185 copies.

Woodcut Images of Creation

The Speculum humane salvationis contains illustrations of related scenes from the Old and New Testament. All the woodcut illustrations are in Dutch style. Approximately twenty pages of the text were printed from blocks; the remainder were set in movable type. The difference immediately strikes the eye, because the texts produced by woodblock are the traditional sepia and those printed from movable type are black. This traditional block book was printed using only one side of the paper.

Adam and Eve from Story of Salvation

These hand-colored drawings illustrate the Biblical account of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. In the middle ages, Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Mirror of human salvation), written anonymously around 1300, was a common religious book. Several hundred copies exist in the form of manuscripts, blockbooks, and early printed books, such as this one. The work is an illustrated Bible that links related episodes from the Old and New Testaments to show the Christian history of human salvation, with a focus on the roles played by Christ and the Virgin Mary.

Medieval Adam and Eve

This Latin book of hours, printed on vellum with colored woodcuts, is an example of an extravagant genre of late medieval piety that flourished in prosperous lay circles. Elegant borders, both fanciful and naturalistic, are a trademark of such works, which were produced both as manuscripts and as printed books in late medieval and early modern times. The fine, detailed coloring, which appears throughout this volume, reflects the precious nature of this book and the wealthy class for which it was painted.

This Latin book of hours, printed on vellum with colored woodcuts, is an example of an extravagant genre of late medieval piety that flourished in prosperous lay circles. Elegant borders, both fanciful and naturalistic, are a trademark of such works, which were produced both as manuscripts and as printed books in late medieval and early modern times. The fine, detailed coloring, which appears throughout this volume, reflects the precious nature of this book and the wealthy class for which it was painted.

Rare Armenian Religious Scroll

Adam and Eve are depicted in the upper left corner of this rare, published Armenian prayer scroll (hmayil), most likely printed in Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1725 and newly acquired by the Library of Congress. Between the late seventeenth and the early nineteenth centuries, Armenians began to produce religious works like this one for domestic use. Usually in manuscript form, prayer scrolls are always profusely illustrated at the beginning of chapters and throughout the text, which includes prayers, biblical narratives, lists and portraits of saints, religious poetry, and magical texts.

Early Spiritual Influences

This life of Christ was immensely popular spiritual reading in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance periods. It was circulated in manuscript and print versions and translated into other languages from Latin. The Vita influenced many people, including Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits.

This Dutch version is notable for the originality of the woodcut designs and the quality and care with which the watercolor was applied as shown in this image of Adam and Eve.

The Book of Adam

The Armenians were long fascinated with the biblical Adam and Eve and created an extensive literature on the pair, including apocryphal accounts, theological discussions, and magical compositions. The mono-rhythmic Adamagirk by the poet Aakel of Siwnik (1350-1422), was composed sometime between 1401 and 1403. This manuscript is a seventeenth-century copy. The poem is unique both for its length and its detail. A medieval Armenian biblical epic, it begins with the story of the fall of Lucifer and concludes with the resurrection of Christ, considered the new Adam.

Holbein’s Adam and Eve

These images of Adam and Eve tasting the forbidden fruit and being expelled from the Garden of Eden as punishment are among the most significant graphic works of the noted German artist Hans Holbein (1497-1543), who designed ninety-four woodcuts depicting events described in the Old Testament. They were published in various editions with Latin, French, Spanish, and English texts and in complete editions of the Bible. The images are accompanied by citations of the relevant Biblical text along with short Latin explanatory notes.

Greek First Humans

This illustration for The Symposium by Plato (428–347 B.C.), depicts a first human as described by the playwright Aristophanes in the text:

“The primeval man was round, his back and sides forming a circle; and he had four hands and four feet, one head with two faces. . . . He could walk upright as men now do.”

After these humans rebelled against the gods, as Zeus punished them by slicing them in two. Ever since, according to Aristophanes, humans have been driven by love into trying to reunite with their missing half to make a perfect whole.

Prometheus Creates Man

The figures on the far left depict the creation of man as described in ancient Greek mythology. After Zeus assigned the titan (giant) brothers Prometheus and Epimetheus the task of creating man, Prometheus shaped man from mud, and the goddess Athena (Minerva to the Romans) breathed life into the clay figure. This plate is one of 1120 in a work by French scholar Bernard de Montfaucon (1665-1714) in which he reproduces images of ancient monuments that might be useful in the study of the religion, domestic customs, material life, military institutions, and funeral rites of ancient peoples.

Societal Beginnings

“Throughout the inhabited world, in all times and under every circumstance, the myths of man have flourished, and have been the living inspiration of whatever else appeared out of the human body and mind. It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation. Religions, philosophies, arts, the social form of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries of science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep, boil up from the basic, magic ring of myth.”

Joseph Campbell

Chronicles of Java

This illuminated manuscript in old Javanese tells the history of Java and the spread of Islam by saints and rulers up to 1647. It seeks to give the state of Mataram legitimacy by finding its beginnings in multiple sacral sources and traditions and by describing an earlier ruler and ancestor as having been blessed by a Muslim saint, practicing Hindu asceticism, and having married the goddess of the southern ocean. The elaborate “carpet page” is typical of Islamic manuscripts elsewhere. This manuscript is a copy of one originally produced in the late seventeenth century.

Early History of Hungary

Containing numerous woodcuts of Hungarian kings as well as battle scenes such as the one shown, Chronicae Hungariae by Ja’nos Thuro’czy (ca. 1435-ca. 1489) is recognized as the most comprehensive Hungarian historical work of its period.

An official under King Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490), Thuro’czy based the early sections on existing chronicles and manuscripts, to which he added interpretations. For the period after 1386, he consulted primary sources such as diplomatic records and the correspondence of significant historical figures.

Armenian National Epic

Composed between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, the Armenian national epic, known as Sasunts’i Dawit (David of Sasun) or Sasna Tsrer (The Daredevils of Sasun) intertwines and preserves Armenian traditions from the pagan past with the religious beliefs of this long-Christian people then living under Islamic rule. In this prose retelling of the epic by the noted twentieth-century Armenian author, Nairi Zaryan (1900-1969), artist M. Sosoyan colorfully portrays Mher the Great, father of the epic’s hero, David, slaying a lion in the presence of military leaders and elders. Thereafter he was known as “the Lion, Mher.”

Origins of French Monarchy

This five-volume history on the origins of the French nation and the development of its monarchy was written by the Benedictine Bernard de Montfaucon (1655-1741), a noted scholar of antiquity. Along with many other historical writers of the period, Montfaucon sought to establish a modern national identity in France’s Greco-Roman past. This work, one of the most important of the period, set the standard for historical method and stimulated numerous other works on the origins of the modern European state.

Hayk Enters Armenia

Armenians trace their beginnings to the hero Hayk, who led their successful rebellion against Babylon and emigration to the new homeland of Armenia. Armenians call themselves Hay and their country “Hayastan” after their hero. This lithograph, which shows the hero and his conquering troops with Mt. Ararat and the ark of Hayk’s reputed ancestor Noah in the background, is from the enormously influential Patmutiwn Hayots, considered the first history of Armenia composed according to modern historiographical methods.

Two Holy Cities

This Muslim prayer book shows the two holiest cities of Islam: Mecca and Medina. Mecca is the most sacred city in Islam, where the Prophet Muhammad was born and lived for the first fifty years of his life.

It is also where the Ka`bah is found, the holiest sanctuary in Islam called the “house of God” (Bayt Allah). Muslims throughout the world pray facing in the direction of Mecca and the Ka`bah.

Medina is the second most sacred city in Islam, where the Prophet Muhammad sought refuge, died, and was entombed.

A History of Three African Peoples

When this translation from the original Xhosa text, written by Reverend John Henderson Soga, was published in 1930, the work was considered to be “the first considerable attempt made by an educated man of Bantu descent and in touch with Bantu tradition, to present the History of his people.” The linguistic term “Bantu” refers to a group of more than 500 languages spoken by peoples living mostly in Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa.

First Icelandic Settlements

Originally compiled in twelfth-century Iceland, the Landnámabók lists the origins, descendants, and landholdings of Iceland’s first settlers, who arrived from Norway in the ninth and tenth centuries. Traditionally, the first Icelandic settler was Ingólfr Arnarson, a Norwegian who came ashore at what is now Iceland’s capitol, Reykjavík, in 874. Landnámabók, known as the “Book of Settlements,” literally means “land-taking book.” Some of the lively biographies in this work served as the basis of Icelandic sagas.

Fundamental Laws of Iceland

This copy of the Jónsbók (John’s Book), an Icelandic legal code, is noteworthy for its unusual Gothic script and decoration. The rule of law was important to medieval Icelanders, as they settled in the new land and established their society. The Jónsbók is a collection of laws imposed on Iceland by the Norwegian king in 1280 and was recorded in many manuscripts and early printings by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Copies were in great demand because Icelandic boys were required to memorize the code, and men carried the book to every courthouse meeting.

Founding of Rome

This illustration portrays the mythic founders of the city of Rome, the twins Romulus and Remus. According to the myth, the twins were sons of the god Mars by a mortal princess, were abandoned as babies, and later rescued by a she-wolf, who suckled them on the Palatine Hill. This depiction is in a copy of a rare guidebook for pilgrims to Rome. Both the text and the illustrations were printed from woodcut blocks, a method soon abandoned with the advent of printing with movable type.

“To be unacquainted with events which took place before our birth is always to remain a child. Intelligent existence loses its meaning, without the aid of history to bring recent events into direct continuity with the past.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero, 64 B.C.

The Founding of Tenochtitlan

According to legend, the tribal god Huitzilopochtli led the Aztecs/Mexica to a spot where an eagle sat atop a prickly pear cactus (tenochtli) growing out of a rock and told them to build their capital there. This symbol now graces the Mexican flag. This image first appeared in the Codex Mendoza, a pictorial history of the Aztecs/Mexica, presumably prepared for the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio Mendoza, ca. 1541. The original reposes in the Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

Early Biblical Atlas

Dutch cartographers from the sixteenth through the seventeenth centuries often prepared maps with biblical themes for publication in their ornate world atlases or as separate illustrations for their Bibles. In this publication, six biblical maps were bound as a collection, representing one of the first separately published biblical atlases. This particular map, which focuses on the era of the Patriarchs, includes Nineveh, Haran, and Ur, and the area through which Abraham and Jacob traveled to reach Canaan, their promised land.

Map Showing Abraham’s Travels

Dutch cartographers from the sixteenth through the seventeenth centuries often prepared maps with biblical themes for publication in their ornate world atlases or as separate illustrations for their Bibles. This English edition of the first modern world atlas, The Theatre of the Whole World, compiled by Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598), contains a section of maps illustrating classsical and biblical history. This particular map focuses on the beginnings of the Jewish nation by depicting the life and travels of the patriarch Abraham. It not only highlights the promised land of Canaan, but also includes an inset showing Abraham’s journey from Ur in Babylonia and marginal vignettes illustrating the major events in his life.

How Bali Became an Island

An acclaimed painter and illustrator born in Mexico City, Miguel Covarrubias (1904-1957) traveled to Bali twice in the early 1930s and subsequently published The Island of Bali (1937). This page, from the working draft of the book, tells the legend of how Bali became an island when the Javanese king emphasized the banishment of his son to Bali by drawing a line through the sand connecting the two lands.

Ethiopia’s National Saint

This manuscript tells the story of St. Takla Hymnot (d. ca.1313), a central figure in the establishment of Ethiopian national identity. In the left illustration, Takla defeats sorcerers, witch-doctors, and demon-worshipers. At right, he converts his long-time enemy, King Motalame of Damot, to Christianity. Takla is credited with restoring the monarchy that claimed descent from Solomon and the Queen of Sheba as well as many miracles. For example, when the Devil cut a rope he was climbing to a hill-top monastery, Takla sprouted the six wings with which he is often shown and flew to safety.

Book of Kings

Beloved by those in the Iranian world since its creation in the tenth century, the Persian epic Shah Namah by Firdawsi (940-1020) is justifiably considered one of the great treasures of world literature. A repository of the history and literary devices of Persia before Islam, it combines these older elements with motifs prevalent in the Islamic world to present a view both grand and intimate. Here in a sixteenth century miniature the hero of the epic, Rustam, is tossed into the sea by the demon Akwan.

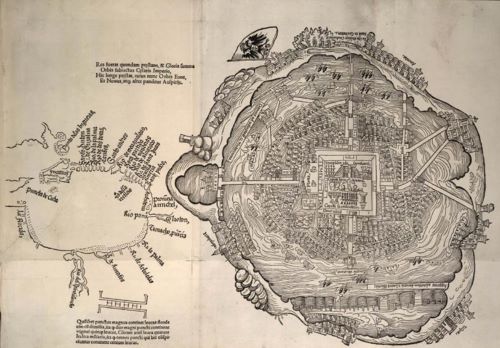

First Map of Mexico City

Soon after his arrival in present-day Mexico, Hernán Cortés (ca. 1484-1547) wrote letters justifying his actions to his sovereign, Emperor Charles V (reigned 1519-1558). In his second letter, dated 1524, Cortés described for the emperor his founding of Mexico City over the ruins of the Aztec/Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan. The original of this first map of Mexico City was probably made by Aztecs/Mexica as a gift to Cortés in 1519 and shows the central locations of the Aztec city as well as those for new structures Cortes planned to build on its ruins.

The State of Nature and Society

“The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1762

A Civil Society

French author and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) published The Social Contract, perhaps his most influential work, in 1762. In this treatise, Rousseau suggests that man once lived in a “state of nature,” enjoying complete freedom. Rousseau argued that people had to fashion a civil society that they could control and in which they could be free.

A Great Artificial Monster

In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes, influential English philosopher, described man in a “state of nature” as living a harsh and violent life. To end this unacceptable condition, men make a social contract with each other to give up their freedom to a ruler whose only obligation is to protect the people. For Hobbes the state was a great artificial monster or a “leviathan.”

A Just Government

John Locke, a seventeenth-century philosopher, explored the foundations of individual understanding and political governance. In Two Treatises on Government, he imagined a state of nature in which individuals relied only upon their own strength. He then described how people left this precarious condition to accept a social contract under which the state gains legitimacy by protecting its citizens. According to Locke, a just government depends on the consent of those who are governed, which may be withdrawn at any time.

In the Beginning was the Deed

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) developed theories concerning human psychology, society and culture. Freud believed that society creates mechanisms to ensure social control of human instincts. At the root of these controlling mechanisms, he thought, is the prohibition against incest. In Totem and Taboo, he speculated that this taboo had its genesis in the guilt stemming from the murder of a powerful patriarch. Thus, he wrote, echoing Goethe, “In the beginning was the Deed!”

Queen of Sheba

“When Queen Magda [Queen of Sheba] had heard all these stories her soul was drawn to Solomon and she knew no desire but to go and greet this king. . . . Thereupon the Queen set out with much state and majesty and gladness, for by the Will of the Lord, she wished in her heart to make this journey to Jerusalem, to rejoice in the Wisdom of Solomon.”

Kebra Negast (Glory of the Kings)

“In the Beginning a Serpent ruled Ethiopia” — so begins text on this fabric version of the story of Makeda, the Queen of Sheba. The story of her voyage and encounter with King Solomon of Israel has been told for generations and recorded in the Bible and the Kebra Negast, the official Ethiopian account. Haile Selassie I (1892-1975), the last emperor of Ethiopia, claimed his descent from Menelik, the son of the queen and Solomon, and thus his authority to rule as part of the Solomonic dynasty of that country.

Rule of Law

“The Law is what it is–a majestic edifice, sheltering all of us, each stone of which rests on another.”

John Galsworthy, 1910

Rules for Daily Living

Completed in 1517, this text became the authoritative source of many of the laws of the Ottoman Empire until reforms occurred in the nineteenth century. This manuscript contains rules covering practically every human activity-spiritual rites, domestic relations, inheritance, commercial transactions, and crimes. Written by Ibrahim Al-Halabi, one of the most learned legal scholars in the sixteenth-century Ottoman Empire, the work has annotations within the main body and all around the margins, made by various commentators, some of whom have initialed their remarks.

French Customary Law

This illuminated legal manuscript is one of the treasures of the Library of Congress. Probably prepared as a presentation copy, this unique manuscript has numerous engravings and illuminations. The text of the law and commentary are in French, followed by the text of law in Latin. The Customary Laws of Normandy is especially valuable to the comparative scholar, because it is more akin to English common law than to French civil law.

Miniature Copy of 1861 Emancipation Manifesto

This miniature copy of three reform laws initiated by Tsar Alexander II 9reigned 1855-1881), with the tsar’s crest on the cover, includes the 1861 Emancipation Manifesto that abolished serfdom in Russia. Approximately 23 million serfs gained personal freedom and a grant of land. (Serfs were farmers bound to a hereditary plot of land and to the will of a landlord.) Although the reform aroused great hopes, emancipation did not help most serfs because many uncooperative nobles gave serfs land that was useful for little more than subsistence. Nonetheless, the manifesto was an important step that led to social change in Russia. This volume may have been made for Alexander himself in commemoration of his reform measures or for him to give as a gift.

Oldest German Law Code

This illuminated manuscript records one of the oldest and most influential German law codes. Between 1220 and 1235, the Sachsenspiegel (Mirror of the Saxons) was written by Eike of Repgow (1180-1235) to record and thus to stabilize what until the thirteenth century was an oral tradition. The book contains information on a wide variety of legal topics, including administration of the law; penal law; laws concerning inheritance, dowries, and marriage; property law; and laws governing the herding, keeping, and hunting of animals. Written for those charged with administering the law, the Sachsenspiegel was widely disseminated in Germany and beyond.

Early Native American Legal Testimony

This is one of eight sheets prepared by the Nahua Indians of Huejotzingo to protest the excessive tribute they were forced to pay the Spanish colonial administrators whom Hernando Cortés had left in charge. When Cortés returned, the Nahua people joined him in a legal case against those Spanish administrators. The codex gives a precise accounting of what the people of Huejotzingo were required to provide. The displayed sheet is a record of the amount of gold and feathers the Indians provided to produce a banner of the Madonna and child for a Spanish military campaign.

Principles of Individual Liberty

Among the Law Library’s rarest books, this miniature manuscript is still in its original pigskin wrapper. Intricate colored pen work graces this small version of the Magna Carta, the basic source of English common law. The Magna Carta established the principle that no one, not even the king, is above the law. The principles of individual liberty it confirmed influenced later political thinkers, including Thomas Jefferson.

Carta of Imperial Russia

Granted by Empress Catherine II in 1785, this document may be regarded as a Russian Magna Carta. The carta concluded the legal consolidation of Russian nobility as a class and provided for its political and corporate rights, privileges, and principles of self-organization. Initially intended to apply only to nobility, the Carta contained ideas of liberty, which were later interpreted to extend to others. In this printing, the imperial title is hand written in gold and is surrounded by engraved coats of arms of the provinces of the Russian Empire.

Constitution of India, 1949

This book is one of 1000 photolithographed reproductions made in 1955 of the Constitution of the Republic of India, ratified in 1949, two years after India became independent of Britain. Concern for the rights of citizens is the basic principle established in the constitution, which sought to assimilate the various linguistic regions and religious groups of India into a cohesive nation. The opening page, shown, contains language echoing that of the Constitution of the United States. Borders, illuminated with real gold in the original, surround the text and illustrations, in Indian art styles of various times.

Views of the Universe

The Emperor’s Astronomy

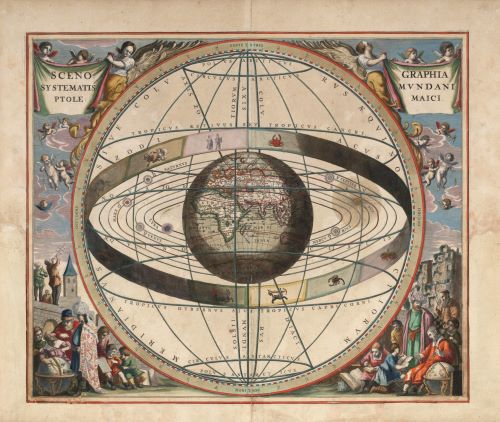

The “Emperor’s Astronomy”(dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) elegantly depicts the cosmos and heavens according to the 1400-year-old Ptolemaic system, which maintained that the sun revolved around the earth. By means of hand-colored maps and moveable paper parts (volvelles), Petrus Apianus (1495-1552) laid out the mechanics of a universe that was earth- and human-centered. Within three years of Apianus’s book, this view was challenged by Copernicus’s assertion that the earth revolved around the sun, making this elaborate publication outdated.

Popular Sixteenth-Century Scientific Work

Cosmographia (1524) by German mathematician Petrus Apianus (1492-1552) provides a layman’s introduction to subjects such as astronomy, geography, cartography, surveying, navigation, and mathematical instruments. In this popular edition with changes by another noted mathematician, Gemma Frisius (1508-1555), movable paper instruments (volvelles) enabled readers to solve calendar problems and find the positions of the sun, moon, and the planets. Apianus depicted the cosmos according to the 1400-year-old Ptolemaic system, which maintained that the sun revolved around the earth, a theory challenged by Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) in Apianus’s lifetime.

A Heliocentric Cosmos

This volume is the first edition of the work that set forth evidence that the earth and other planets revolve around the sun. Written by Polish astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), and published just before his death, the work was met by tremendous opposition because it contradicted religious beliefs of the time. The Copernican views provided the basis for the later work of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Galileo (1564-1642), and Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

Chinese Armillary Sphere

This wood-block printed book from 1633, an expansion of one printed in 1461, illustrates Chinese theories of early astronomy in the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties, when there was great interest in celestial phenomena. The armillary sphere shown indicates the motions of the sun and moon, as well as the stars and constellations. Also, the four seasons are arranged in order according to their progressions and retrogradations.

Ancient Chinese Concept of Change

The book is an explanation of the “Ba Gua” used in the Yi-ching (I Ching or Classic of Changes, also known as the Book of Divination). According to this Chinese world view, the universe is run by a single principle, the Tao, or Great Ultimate. This principle is divided into two opposite principles–yin and yang. All phenomena can be understood using yin-yang and five associated agents, which affect the movements of the stars, the workings of the body, the nature of foods, the qualities of music, the ethical qualities of humans, the progress of time, the operations of government, and even the nature of historical change.

Astronomical Theories

Written in the fourteenth century, this philosophical work incorporates in its fifth chapter the astronomical theories of Levi ben Gershom (1288-1344), one of the greatest medieval astronomers. Gershom’s major contributions to astronomy included the invention of the “Jacob’s Staff,” an instrument that measured visual angles. On the basis of observations made possible by the new invention, he was able to make essential adjustments and corrections to the Ptolemaic system.

Earth-Centered Universe View

This illustration from William Cuningham’s The Cosmographical Glasse (1559) represents Ptolemy’s conception of the universe. Atlas, dressed like an ancient king, bears on his shoulders an armillary sphere representing the universe. In the center of the sphere is earth, made up of the elements of earth and water. Surrounding the earth are two more elemental spheres, for air and for fire. Other bands represent the spheres of the planets, the firmament of fixed stars, the crystalline sphere, the primum mobile, and the signs of the zodiac. Below Atlas are lines on cosmological themes from Virgil’s Aeneid.

Earth, Air, Fire, and Water

The thirteenth-century De proprietatibus rerum (The Properties of Things) preserved and distilled much learning from antiquity as well as the Middle Ages. For more than two centuries Europeans pondered the material world through this encyclopedic text, circulated in both Latin and vernacular manuscripts like this French one. In it are Ptolemy’s scheme of the planets and Aristotle’s theories of the structure of matter (shown) in the illustration. For Aristotle, the elements of earth, air, fire, and water were different aspects of a single substance called “primary matter.”

Descartes’s Mechanical Philosophy

According to French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650), the universe operated as a continuously running machine which God had set in motion. Since he rejected Newton’s theory of gravity and idea of a vacuum in space, Descartes argued that instead the universe was composed of a “subtle matter” he named “plenum,” which swirled in vortices like whirlpools and actually moved the planets by contact. Here, these vortices carry the planets around the Sun.

Galileo’s Views of the Moon

The first telescopic drawings of the Moon were made and published by Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) in 1610. Because he showed the Moon to be a solid body with irregular surface features, he would later argue that the Earth was not unique. Using simple geometry, he used the shadows cast by the lunar mountains to calculate correctly their height. This led to his disagreement with Aristotle’s theory of an immutable universe and to his controversial defense of the Copernican system in 1632.

First Atlas of the Moon

Thirty-seven years after Galileo (1564-1642) made the first drawings of the moon as it looked through his telescope, the famous Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687) published Selenographia, the first lunar atlas. The book also deals with the construction of telescopes and with the observation of celestial bodies in general. The author himself engraved the 110 illustrations, including the large double-paged maps of the moon, one of which is shown. The level of detail reveals the rapid advances in telescope optics that had taken place since Galileo’s 1610 moon drawings.

Picturing the Universe

Before the revolutionary, sun-centered ideas of Copernicus, the traditional geocentric or earth-centered universe was usually depicted by concentric circles. In this popular German work on natural history, medicine, and science, Konrad von Megenberg (1309-1374) depicted the universe in a most unusual but effective manner. The seven known planets are contained within straight horizontal bands which separate the Earth below from Heaven, populated by the saints, above.

The Four Elements

The illustration from this French edition of the thirteenth-century encyclopedic work De proprietatibus rerum (The Properties of Things) shows Christ as creator standing on an orb of the world to proclaim his earthly supremacy. With his right hand, He manipulates fire while His left hand gestures toward the earth. By tradition, these two elements were the starting materials for creation. Air in the upper right circle and water in the lower left one stand ready for use between the two extremes of fire and earth. Medieval European scholars learned the theory of the elements from the works of Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), who for nearly two thousand years was considered the supreme authority on all physical matters.

Buddhist Cosmological Map

The Buddhist (monk) Zonto created a trilogy of scroll maps–one of the Buddhist mythological world and the real world, one of India with old Buddhist names and descriptions, and this one representing the Buddhist philosophical world. This stepped diagram has the relatively small actual world (the small green and orange area) sandwiched between seven levels of hell and seven levels of heaven. The actual world map, which has India at the center with China and Japan large and Europe small, shows Western influences and includes America.

The second map represents the Buddhist mythological and real worlds. The upper half of the map depicts the seven great forests interwoven with seven rivers, the Sun God Palace, and the “Great Jambu Tree.” The tree is described as 10,000 miles high and bearing the most delicious fruits. Only those who cultivated the divine power can visit the tree. The central section is the Sun God Palace in heaven.

Traditional Korean Maps

From the oldest known examples (perhaps from the sixteenth century) to almost the end of the tradition in the nineteenth century, the content and structure of traditional Korean maps such as these examples changed very little. The map of the world (or Chonhado) presents Korea, China, and their East Asian neighbors surrounded by rings of exotic, mythical lands and peoples and reflects the traditional Korean view that the world was flat. Being a peninsula, Korea stood out on the map and was close to China, the classical center of Asian civilization. Korean military security concerns about China and Japan stimulated the creation of maps such as the one of Korea only, which provides information on the military and naval defenses of Korea’s eight provinces. The map of Cholla Province, the southwestern part of Korea, is typical of the atlases of individual provinces which were prepared during the Yi Dynasty (1392-1910).

Persian Celestial Globe

While most globes constructed prior to 1900 are hollow and made of plaster, this globe is a solid wooden sphere on which the celestial information is delicately painted. The constellations are configured according to Arabic tradition. Of the seventy pre-1900 globes in the Library’s collection, this is the only one representing traditional Islamic astronomy, and, of the Islamic globes currently held in the United States, this is the only wooden one.

Earliest Globe in the Library’s Collections

This finely crafted terrestrial globe within an armillary sphere is the work of Caspar Vopell (1511-1561), a German mathematics teacher and scholar. Vopell depicts North American and Asia as one land mass, a common misconception of the time. The armillary sphere, with its interlocking rings that illustrate the circles of the sun, moon, known planets, and important stars as well as the signs of the zodiac, is a model of the Ptolemaic or earth-centered cosmic system. Ironically, the globe was constructed in the same year that Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) published his revolutionary theory that the sun is the center of the solar system.

Exploring and Ordering the Heavens

Tibetan Astrological Thangka

Tibetan astrology depicts the signs and symbols of the universe in this traditional format, possibly introduced from China as early as the seventh century and popular in Tibet since the seventeenth century. The central figure is a large golden tortoise, representing the Bodhisattva of Knowledge, upon whom are drawn various geomantic diagrams, such as the nine magic squares and symbols of the eight planets. This type of Thangka is often hung in homes for protection and displayed for special occasions.

Egyptian Zodiac

French scientists and artists accompanying Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 produced Description de l’Égypte, a twenty-two volume publication that essentially established the modern science of Egyptology. Here is an engraving of an ancient Egyptian diagram of the heavens from the Temple of Dendara, depicting the sky on the date of the founding of the temple in 54 B.C. The falcon-headed gods symbolize eternity and the goddesses relate to the four directions.

Astronomy and Astrology

Initially Muslim astronomers believed that the earth rested motionless at the center of a series of eight spheres, the last of which was studded with fixed stars revolving daily from east to west, and at times from west to east. Muslim astronomers were influenced by Sanskrit, Sasanian, Syraic, and Greek texts on astronomy, which they amended. Rami, the Sagitarius in this illustration from an eighteenth-century copy of a book by ‘Abd al Rahman ibn ‘Umar al-Sufi (d. 986), has a set of twenty-nine gold spots that represents a stellar constellation.

Illustrated Calendrical Observations

This book is one in a three-volume set whose illustrations include the author’s seasonal observations of lunar eclipses. The set is one over four hundred traditional Japanese mathematics volumes, called wasan, found in the Library’s collection. With its complex algebraic formulae and the study of geometric figures, wasan was used by members of the samurai and later of the merchant class. In 1872, the Meiji government discouraged the teaching of wasan in Japanese schools and promoted the teaching of Western mathematics.

Constellations from Classical Antiquity

The star charts of Reiner Ottens (1698-1750) were intended first and foremost as a feast for the eye and had no pretensions to scientific precision or the presentation of the most recent cartographic information. The constellations on this chart are elaborately represented by figures from classical antiquity. In the corners of the chart are illustrations of four European observatories, including that of the noted sixteenth-century astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601). This atlas is a seven-volume compendium of assembled-to-order star charts and geographical maps.

Astronomy Cards

Some of the most splendid star charts of all time appeared in the only Dutch celestial atlas, Harmonia macrocosmica . . . , by Andreas Cellarius. The true purpose of this great atlas was scientific and Cellarius’s charts reflect the highest levels of seventeenth century astronomical theory and observation. This chart from the second edition of the atlas (1708) shows the constellations in the form of Christian saints, in contrast to the better known patterns of classical antiquity which were based on the writings of second century geographer Claudius Ptolemy.

Constellations as Christian Saints

Some of the most splendid star charts of all time appeared in the only Dutch celestial atlas, Harmonia macrocosmica . . . , by Andreas Cellarius. The true purpose of this great atlas was scientific and Cellarius’s charts reflect the highest levels of seventeenth century astronomical theory and observation. This chart from the second edition of the atlas (1708) shows the constellations in the form of Christian saints, in contrast to the better known patterns of classical antiquity which were based on the writings of second century geographer Claudius Ptolemy.

The Nine Hindu Planets

In Hindu astrology human destinies and earthly events are ruled by nine planets, namely the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, and the ascending and descending nodes of the moon (the points where eclipses take place). The word for “planet” is graha, “grabber,” and is also applied to supernatural beings that possess people or cause illness. The deities of these nine planets are portrayed in a folding book (thyasapu) from Nepal, written in the Newari and Sanskrit languages. The spells or prayers (mantras) for dealing with the deities’ adverse effects are also given.

The Moon and Sun in Their Chariots

In Hindu astrology human destinies and earthly events are ruled by nine planets, namely the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, and the ascending and descending nodes of the moon (the points where eclipses take place). In this nineteenth-century book in Hindi and Sanskrit, the gods Chandra (the Moon) and Surya (the Sun) are shown. In India the moon disk is thought to show either a deer or a hare. Consequently the moon’s chariot is shown drawn by deer or, as in this image, by gazelles. Because the sun is associated with horses, they pull his chariot. The book gives instructions on talismans and rituals to protect against the adverse influences of planetary deities.

The Heavens

In the doctrine of Theravada Buddhism, as in other religions of Indian origin, a sentient being may transmigrate through an endless series of lives as a human being, an animal, a denizen of the hells, a god, or other supernatural being. The many heavens for various sorts of gods are temporary abodes only, and the ultimate goal is not to stay in them forever but to escape from the whole cycle to Nirvana. This Burmese folding manuscript, probably from the eighteenth century, shows a number of these heavens as floating palaces and describes their different names and properties.

Transmission of Classical Astronomy to the West

The frontispiece of this copy of his most famous work shows the Islamic astrologer, Jafar Ibn Muhammad Abu Mashar al-Balkhi (805(?)-886), known as Abu Mashar holding an armillary sphere. Despite his emphasis on astrology, Abu Mashar was a key link in the transmission of Hellenistic astronomy to the West. For instance, Abu Mashar consulted Greek texts when he wrote. His work was translated from Arabic into Latin in the twelfth century and was held in great esteem by Medival and Renaissance intellectuals.

Ordering Time

There by to see the minutes how they run;

William Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 3

How many make the hour full complete,

How many hours bring about the day,

How many days will finish up the year,

How many years a mortal man may live.

Indian Almanac

Almanacs (pancangas) are used by many Hindus to regulate most activities in accordance with the good and bad positions of the heavenly bodies and lucky and unlucky days and to determine the dates of various religious festivals. Very few illustrated manuscript almanacs survive because most were used and discarded or cut up and sold by antique dealers. This one shows a couple on horseback, the elephant-headed god Ganesha, who is invoked as patron of auspicious beginnings, and figures representing deities, the planets, the zodiac, and other astrological phenomena.

Chinese Farmer’s Almanac

Like people engaged in agriculture in other cultures, Chinese farmers observed the changing cycle of the moon and other celestial phenomena to determine when to perform their farming activities. The earliest Chinese farmer’s calendar, on which this seventeenth-century example is based, can be traced back to 5141-5042 B.C.

Aztec Calendar Wheel

The Aztec calendar represents 260 days of thirteen months (each containing twenty days) which determined the life of each Mexica (Aztec). In Aztec society, priests would consult the calendar to determine auspicious days for weddings and other important events. The portion displayed here contains the symbols for each day and the sun, moon, and stars. Fernández Echeverría y Veytia (1718-1780 ) drew these pictures of the calendar wheel in the early nineteenth century from documents written prior to the Spanish conquest in 1521.

Calendar Reform

This manuscript of the mid-nineteenth century, possibly of Sgau Karen origin (the Karen are a minority people in the mountainous parts of Burma), shows various appearances in the sun, the moon, clouds, etc., and indicates the primarily bad omens these appearances foretell. Explanations in English were added to this manuscript by a nineteenth-century American missionary.

Aztec Calendar Stone

In 1790 workers repaving near the Cathedral in Mexico City discovered a stone eleven and one-half feet in diameter inscribed with the Aztec calendar. When in use, the stone would have had bright polychrome colors and would have held sacrificed human hearts that the Aztecs believed were needed to feed the sun and keep civilization alive. This first study (pictured to the left) of the stone explained its 260-day divinatory cycle. The stone’s colossal size, elaborate patterning, and symbolic imagery have made it an unofficial emblem of Mexico.

This book, by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, director of the excavations of the central Aztec temple (Templo Mayor), uses color overlays to show how the stone, known as the “Piedra del sol” (sunstone), would have looked on the Aztec great temple. The volume also includes a facsimile of the first study of the stone published in 1792 by Antonio de León y Gama. Its colossal size, elaborate patterning, and symbolic imagery have made the sunstone an unofficial emblem of Mexico.

Ethiopian Calendar

This Ethiopian manuscript, in the languages of Amharic and Geez, is open to a page explaining the mathematical system for fixing the movable feasts and fasts of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The Ethiopian year consists of 365 days, divided into twelve months of thirty days each plus one additional month of five days (six in leap years). Ethiopian New Year’s Day falls on September 11 and ends the following September 10, according to the Gregorian (Western) calendar.

Sutra of the 1,000 Buddhas

In the Tibetan Buddhist world view, time is measured in kalpas, vast time spans of millions of years, during which things progress and decline, only to begin again. This Mahayana Buddhist sutra describes the Bhadrakalpa, our present aeon, wherein 1,000 Buddhas will appear. This seventeenth-century Tibetan manuscript in two large volumes is written in gold ink on paper. It is illlustrated with over 600 roundels depicting the future Buddhas on loose pages like the one shown.

Japanese Calendar, 1882

Believing that the movements of the heavens and earth controlled human affairs, ancient scholars in East Asia studied astrology and geomancy (divination by line or geographical features) to develop calendars that determined the seasons and human activities. The displayed volume contains calendars followed by the Japanese in their daily life.

Chinese Divination Studies, 1580

Scholars in ancient China studied the natural phenomena of the sky to determine their effects on human destiny. The illustration on the right depicts an eclipse, indicating bloodshed and fighting in the country and the future overthrow of the top official (emperor). In contrast, the illustration on the left, showing a rabbit in the moon (rather than a man, as in European folklore), is a good omen. A bright moon indicates that prosperity is at hand.

The Jewish Lunisolar Calendar

Because the Jewish calendar is lunisolar–the months being reckoned by the moon and the year by the sun–astronomical expertise is needed to harmonize the two so that religious obligations can be discharged on the correct days and at their appointed times. This edition (the fifth) of Eliezer ben Jacob Belin’s Sefer Ebronot, published in Offenbach, Germany, in 1722, is noted for its astronomical-mathematical charts and illustrations. Notable among these are the circular chart and the multilayered paper volvelles.

Views of the Earth

The Tao is called the Great Mother;

Lao-tzu, Tao Te Ching

Empty yet inexhaustible,

it gives birth to infinite worlds.

Jaina World View

Jainism, an Indian religion distinct from Hinduism and Buddhism, was founded by Vardhamana Mahavira, called “the Jina” (conqueror), who lived in the sixth century B.C. Among other variations from Hindu culture, Jainism has its own version of geography and cosmology. This chart from the nineteenth century shows the world of human habitation as a central continent with mountain ranges and rivers, surrounded by a series of concentric oceans (with swimmers and fish) and ring-shaped continents.

Sacred Cows

This poster represents the figure of the cow as containing all the Hindu gods and quotes Sanskrit texts: O noble folk, protect the cow, who protects your stomach, for . . .

“Brahma is in her back, Vishnu in her throat, Rudra (i.e. Shiva) is established on her face . . . Sun and Moon are in her eyes . . .”

This poster was published by an organization dedicated to the protection of cattle and to convincing all people that cattle should not be slaughtered or eaten.

The world was made, not in time, but simultaneously with time. There was no time before the world.

St. Augustine, Confessions, 397

Medieval Islamic Map of the World

At the center of the map are the two holiest cities of Islam: Mecca and Medina. The map shows China and India in the north and the “Christian sects and the states of Byzantium” in the south. The outer circles represent the seas. The manuscript is a cosmology, not meant to be accurate geographically, but only to present the reader with a systematic overview of the existing knowledge about the world at the time.

Islamic World Map

This geographical treatise and collection of wondrous tales was exceedingly popular in mediaeval and early modern Islamic society. The map shown here is unusual in its portrayal of several creatures supporting the world in the firmament. While it uses a traditional Islamic projection of the world as a flat disk surrounded by the sundering seas which are restrained by the encircling mountains of Qaf, the map also shows the Ottomans’ early use of geographic information based upon European cartographic methodologies and explorations.

T-O Map of the World

This is the first printing of the earliest example of a map of the world, called a “T-O Map” because of its symbolic design. Originally drawn in the seventh century as an illustration of Isidore of Seville’s (d. 636) Etymologiarum, an early encyclopedia of world knowledge.

The design had great religious significance, with the “T” representing a mystical Christian symbol of the cross that placed Jerusalem at the center of the world. The “T” also separated the continents of the known world—Asia, Europe, and Africa—and the “O” that enclosed the entire image, represented the medieval idea of the world surrounded by water.

Rescuing the Earth

The Hindu view of the world is cyclic. The universe is destroyed and re-emitted again in endless cycles. Periodically, Vishnu, the great god whose function is to maintain the world, comes into it temporarily in bodily form to rescue it from one disaster or another. Once a great flood swallowed up the entire earth, and Vishnu, taking the form of a gigantic wild boar, plunged to its bottom and brought the earth back up on his tusks. In this illustration, the boar incarnation is flanked by two images of Vishnu in his normal four-armed human shape.

In the second illustration, Vishnu in triumph tramples the demon who had abducted the earth to the ocean bottom. Scroll books are exceedingly rare in India, and this handwritten scroll with its ultra-minuscule script was probably meant as a tour de force and work of piety rather than a reading copy.

Wheel of Life

In the Tibetan Buddhist world view, the six realms of existence (Gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and hell-beings) are all held in the grasp of the Lord of Death. In the center of the wheel are the three root poisons of desire, hatred, and ignorance symbolized by the cock, snake, and pig, and on the outer rim are the twelve links of dependent origination by which all causes and effects are determined. The ultimate goal, shown by the monks in the left inner circle and the Buddha in the upper right, is to follow a path that frees one from these cycles.

The Burmese Buddhist World

In Buddhist cosmology, deriving from Indian origins, the world is viewed as a system of continents and oceans, either in rings (as in the center here) or floating detached in the ocean. This nineteenth-century Burmese manuscript shows in one image both sorts of continents, and a cosmic ocean symbolized by fish, crabs, and snails. Other sections of the book show and describe the various heavens and hells. Folding accordion-style manuscripts on thick paper are common in Southeast Asia, along with loose-leaf manuscripts made from palm leaves.

Celestial View of Earth

Polish born Wladyslaw T. Benda (1873-1948) created eye-catching cover art and illustrations for short stories and essays in leading magazines during America’s golden age of illustration (1870-1930). Benda depicts two timeless figures that frame and contemplate his imagined vista of the earth and moon suspended on the edge of the Milky Way. Light from the lower right throws land masses of North America, Europe, and Africa into bold relief, accentuates the earth’s majestic beauty, and illuminates a visn of earth within its galactic context.

“For it is the duty of an astronomer to compose the history of the celestial motions or hypotheses about them. Since he cannot in any certain way attain to the true causes, he will adopt whatever suppositions enable the motions to be computed correctly from the principles of geometry for the future as well as for the past.”

Andreas Osiander, 1543

Early Maps

Portolan Chart of the Mediterranean World

A cartographic revolution occurred in the Mediterranean world in the thirteenth century with the emergence of a new genre of navigational chart –the portolan chart. Usually drawn on animal skin, portolan charts depicted the coasts of the Mediterranean and Black Seas and the Atlantic of southwestern Europe with a high degree of accuracy.

Displayed is one of the Library’s most colorful portolan charts, which was drawn in 1559 by Mateus Prunes (1532–1594), a leading member of a family of Majorcan cartographers.

Buddhist World Map

Compiled during Japan’s age of national isolation (1636-1854), this world map is representative of Buddhist cosmology. Drawn in 1710 by Htan (1654-1738), a Buddhist monk, it is characteristic of a type of early East Asian map that were not based on objective geographic knowledge, but on the more or less legendary statements in Buddhist literature. The map is centered on India and shows the mythical Anukodatchi-pond, which represents the center of the universe and from which four rivers flow in the four cardinal directions.

Early View of the World

Although published in 1482, this map is based on the writings of Claudius Ptolemy (87-150 A.D.) and presents a composite geographical image of the world as known to classic Greek and Roman scholars. Ptolemy’s geographical writings, known as Geographia or Cosmographia, survived through the Middle Ages in various manuscript copies and was one of the first geographical texts to be put into print.

This edition was the first edition to be printed outside Italy and the first to include maps printed from woodcuts.

The fascination of maps as humanly created documents is found not merely in the extent to which they are objective or accurate. It also lies in their inherent ambivalence and in our ability to tease out new meanings, hidden agendas, and contrasting world views from between the lines on the image.

J. B. Harley

First National Atlas

Christopher Saxton’s (ca. 1542-1606) atlas of England and Wales is the earliest atlas of a country. Based on a monumental survey conducted 1574-1578 under the authority of Queen Elizabeth I, the atlas consists of thirty-four maps depicting fifty-two counties and a general overview of the entire country. The work is graced by a striking illuminated frontispiece that shows the enthroned queen holding a scepter and a globe, reflecting her ambitions of creating a global empire, as well as her role as a patron of astronomy and geography.

Low Country Portrayed as a Lion

With the rise of European nationalism, map making became a tool for fostering emerging national identities. Besides the compilation of detailed national maps and atlases, which established boundaries for individual states, cartographers also developed easily recognized iconography. In the case of the seventeen provinces known variously as “Germania Inferior,” “Les Pays Bas,” “the Netherlands” or “The Low Country” encompassing today’s Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, and part of northern France, were often represented as a lion, referred to as Leo Belgicus.

Measuring the Yellow River

This pictorial map of the Yellow River is both an artistic masterpiece and scientific source of information. The work was completed by ten famous painters representing China’s northern and southern schools. Ordered by T’ai-tsu, the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) the work, executed in true proportions, was an invaluable tool to assess the impact of the frequently flooded Yellow River. The houses in the map indicate the population of the cities, each house representing one hundred families.

Route from Edo to Nagasaki

This scroll map depicts an aerial view of one of the most famous roads in old Japan–the Tokaido–as it looked from 1660 to 1736. This highway was the main land route from Edo to Osaka, which is depicted in the lower portion. The map also shows the land-sea routes from Edo to Nagasaki and includes inns and historic sites. The view is rendered pictorially in watercolor, and there are places where inscriptions are pasted on. The Tokaido became the route of super-express highways and high-speed railroad lines in twentieth-century Japan.

Let us look at the map, for maps, like faces, are the signature of history.

Will Durant

Evoking Spiritual Powers

Book of Incantations and Magical Formulae

Often reprinted, this popular book of practical kabbalah includes incantations and magical formulae. The opening shows an amulet to protect women in childbirth and newborn infants from harmful spirits, in this case, the spirit of Lilith. According to legend, Lilith was Adam’s first wife (before Eve), but left him when he refused to share power equally.

African Fertility Symbol

In Ghana, a pregnant woman carries an Akuaba doll, the symbol of fertility, productiveness, and fruitfulness, in hopes that her expected child will attain the qualities of the doll. The flat, oval head of the Akuaba doll, with stylized eyes and nose, symbolizes holiness, innocence, and beauty. A barren woman may also carry an Akuaba doll in hope that she may become fertile.

Wheel of Fortune

The concept of the “wheel of fortune” was a common idea in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance period. For many people, good fortune and chance were as reliable indicators of personal fate as faith and good works. The spin of the wheel or the toss of the dice were “tried and true” methods of explaining how the unknown worked and gave meaning to what transpired in everyday life. Lorenzo Spirito’s (d. 1496) Book of Fortune, first published in 1482, went through over a dozen editions by 1525, and was especially popular in Catholic countries like Italy.

This illustration from a popular sixteenth-century book is a “wheel of fortune,” which provides the reader an opportunity to ask questions about the future and receive predictions and advice about things to come. The text is entirely in verse and contains witty and sometimes ribald anecdotes, mostly having to do with the choice of a good wife, the quality of this year’s harvest, health, and family relations. The woodcut artists were Heinrich Vogtherr the Elder and Hans Beham, both noted for their broad line design and and strong impressions. In the sixteenth-century books on fortune telling were heavily used, and only a few survive.

Mesopotamian Incantation Bowl

Usually buried in a building’s foundation, magic bowls were designed to protect a house and its inhabitants from demons and evildoers. Opinion differs as to the actual ritual or rite associated with these incantation bowls, but it is generally believed that they were thought to entrap and reject evil powers. The inside inscriptions, in concentric circles, are in Aramaic.

Early Chinese Handwriting

The cryptic inscriptions engraved on bones such as these are the earliest known forms of Chinese handwriting. The inscriptions are questions relating to the ancient Chinese practice of divination, an attempt to foretell the future or discover hidden knowledge by the interpretation of omens. Since the “oracle bones” were first discovered in China at the end of the nineteenth century, more than a hundred thousand pieces have come to light. These pieces came into the Library’s collection before 1928 through a gift to the Library.

When Science from Creation’s face

Thomas Campbell

Enchantment’s veil withdraws

What lovely visions yield their place

To cold material laws.

Early Science