The classical-era Acropolis was a place of bright and variegated colours.

By Dr. William St Clair

Late Senior Research Fellow

Institute of English Studies

School of Advanced Study

University of London

Introduction

How did the people of Athens of the classical period engage with the huge building that they, through their institutions, had caused to be designed and erected? The size of the building, with the statue of Athena Promachos towering above it, drawing eyes from the far and middle distance, has been noted in my companion volume, Who Saved the Parthenon?; so has its function as a focus for the ‘famous hills of Athens’.1 But how was the Parthenon seen, understood, and used from close up?

Who, we can first ask, had access to the Acropolis as a site? Later in antiquity, at some periods, it appears to have been open to citizens and others to be admitted by the guards at the entrance, and visitors are sometimes recorded as paying a small fee.2 For the classical period, there are few contemporaneous mentions other than those concerned with protecting the monuments and the workshops from thieves, evidence in itself that the rhetoric offered by the building was not universally acted upon. We can, however, be sure that among the reasons an individual Athenian citizen might legitimately have for wanting to visit the Acropolis, other than temporarily to escape the interruptions of the town, was a wish to check on some point of law, contract, or treaty that had been set out on a marble inscription; to solemnize a contract; or to be present as a duty when a public or private dedication was made or an inscription formally endorsed as valid, by some ceremony equivalent to unveiling. Other citizens, whether as individuals or as civic officials or members of commissions, might need to inspect the financial accounts, including those relating to building projects. Some office-holders, notably certain young women, were required to live on the Acropolis for fixed periods as part of their duties. The fragmentary inscription of 485/44 required that a physical audit should take place every ten days.3

As for what they saw when they arrived within the Acropolis, although it is now a place of buildings, in classical times it teemed with free-standing dedicated statues and with formal words inscribed on marble. Some contemporary inscriptions, such as one that listed the contributions to the budget of the cities of Ionia, were several metres high and unignorable. Taken together, however, although some secured the most conspicuous locations, they seem not to have been arranged in any geographical or chronological order. There were also, dotted around the Acropolis summit, a growing number of public and private dedications in the form of free-standing statues in the round, and especially of statue-groups, that presented stories, mostly mythic, as already discussed.4 Since they could not be erected without the permission of the authorities, they too can be regarded as contributions to an official history in the form of a built heritage. As accretions occurred, the site offered a layered past, with each statue, statue group, or inscription composed in accordance with its own conventions that, taken together, told an officially approved history, not as a single narrative, but as a collection of primary visual documents from which a large part of the officially-approved civic history, both historic and mythic, could be constructed.

During the fourth century BCE, when the classical Parthenon was in full use for its intended purposes as part of a complex of buildings, the contemporaneous inscriptions suggest that there was a frequent to-ing and fro-ing of temple staff and others concerned with the safeguarding, the management, and the accounting for the portfolio of material assets that were kept behind locked doors within the Parthenon, as well as within other buildings on the summit and elsewhere. Architecturally, the building followed the main Hellenic convention of being divided into two compartments: the Hecatompedon (‘hundred footer’) at the west end, and the ‘Parthenon’ (room where the cult image of the virgin (‘parthenos’) goddess was housed and occasionally displayed) at the east end.5 In Aristophanes’s comedy, the Lysistrata, first performed in 411 BCE, the Acropolis is taken over without difficulty by the chorus of women, who, as part of their plan to end the war, remove money from the public treasury.6 With the topographical details given in the play, we can be sure that the ancient audience were invited to imagine the women entering through the west door behind the colonnade.

To judge from indications on the stonework, those who entered the building through the west door found themselves in a chamber, with little natural light, flanked on each side by Ionic columns, and a corridor to the inner dividing wall.7 The chamber was arranged as a warehouse with stacks of shelves and boxes on the other sides of a corridor that may have led to a door through to the rear of the other chamber.8 Even though, for a chamber used primarily for storage, something plainer would have met the purpose, the opportunity was taken to present a kinship feature that may have been designed to please both the Athenian families who claimed to be autochthonous Ionians, and the overseas Ionians whose contributions to the collective treasury were deposited there.

About two hundred ancient inscriptions carved on marble have been published in recent centuries; material that made the wording difficult to change and ensured both fixity and security against the tampering to which documents on perishable materials were exposed. This is a fragmentary sample, which is unlikely to be representative, of a much larger number that has since disappeared. In ancient times, one of the functions of these inscriptions, we can be confident from their wording, was to perform as publicly accessible inventories of items stored and safeguarded inside. Besides some denominated in monetary terms in drachmas and obols, the inscriptions refer to items made of silver and gold, such as wreaths, which are denominated by weight as well as in drachmas and obols—weight being a denominator more suited to inventory and audit than any monetary unit whose exchange value in terms of purchasing power was never steady. The wording reveals that objects made from these two metals were sometimes melted down if they became damaged, reverting to the status of bullion. As ‘useful things’ (‘chremata’), both the ‘signed’, that is, the monetary, and non-monetary metal objects were convertible in both directions. By incurring a small manufacturing cost, bullion could be converted into coin, a process that, through seignorage, would normally produce a net profit for the Athenian state.

Judging from the wording, some items listed as held in the stores were awarded as prizes in festivals on condition that they were returned, and so became available to be awarded again on later occasions. As for objects not so described, it is not known the extent to which they were intended to be held permanently in the repositories as assets to be put to no further active use after the initial performance ceremony of dedication. If so, they continued to perform only on the occasions when the permanent inscriptions outside were encountered, read, and believed to be true, or untrue, by readers. In such cases, the permanent inscriptions were the equivalent of those still inscribed on modern banknotes that still purport to represent metal presented as intrinsically valuable, even when it cannot be exchanged for metal except among central banks, and its origin in metal is only deemed or ‘nomismatic’.9 Nor was deliberate deception a negligible risk. With plentiful resort to Thucydidean speeches that bring out the wider issues, Thucydides tells how the Egestans, as a way of drawing the Athenians into a war in which they had no stake as kinsmen, fooled them into believing that their temple, which was comparable in size to the Parthenon, contained more ‘chremata’ than it actually did.10

It seems likely, however, that many of the other items deposited in the Parthenon and other buildings were brought out from storage to be used in actual festivals. The ‘tables’ and ‘couches’ appear to be pieces of general-purpose furniture to which detachable specialized metal ornaments might be added. Among the smaller items inventoried are incense burners, trays, wine jugs, drinking cups, baskets, lamps, swords, shields, stools, musical instruments, wreaths, necklaces, bracelets, clothes, an iron knife presumably for the ritual slaughtering of animals, the standard paraphernalia of ancient processions and ceremonies, both real and as projected back to mythic times, as on the Parthenon frieze.11 The lists also give evidence of wear and tear, or of theft or vandalism, such as parts of tables, parts of cauldrons, and parts broken from the doors. Among the unusual items listed are golden ornaments that include grasshoppers or cicadas, a symbol of the autochthony of the old Ionians of Athens, and an example of the Ionian origin and kinship claim whose role in the discursive environment is confirmed by the experiment.12 As a public presentation of autochthony, the golden cicadas, as with other features of the Parthenon, linked the symbolism with the viewerly experience. As was noted by an ancient scholiast on Thucydides, and confirmed by modern observation, since the larvae of cicadas are buried underground, the emerging insects do appear, as Thucydides remarked, to be ‘earth-born’.13

There are also records of documents written on perishable materials held in safe and accessible repositories.14 The inventories for the Acropolis buildings, for example, note ‘a writing tablet from the council (‘boule’) of the Areopagus sealed’, evidently an official record of importance. The Athenian authorities were evidently well aware of the risks to which documents written on perishable materials were exposed from fire, forgery, and manipulation. In the Clouds, the comedy by Aristophanes, the character of Strepsiades, by turning a glass normally used for starting a fire by redirecting the sun’s rays, manages to melt the wax and destroy the words on a document that records the amount of his debt.15 We may have here a glimpse of a tilt from memory held orally towards memory as checkable documentation that, in the case of Athens, accompanied the transition from an oikos economy, which produced its own means of subsistence internally as described by Thucydides, to one in which commodities, notably olive oil, were grown to be sold into markets, denominated in monetary terms, and mutual obligations recorded.16

But what, I now ask, occurred at festivals, to provide a backdrop for which, my experiment suggests, was the most important function of the Parthenon? What was the experience of arriving visitors when they were first able to make out for themselves the composition presented on the west pediment, the only part of the building that offered stories that were visible from ground level?17

In an influential book, Architectural Space in Ancient Greece, first published in 1972 but derived from researches done in pre-war Berlin and on the spot in Greece, the architect and planner Constantinos A. Doxiadis selected the now familiar iconic view of the Parthenon as seen from the west to exemplify his theory that the ancients had selected various stopping points on the Acropolis summit where the sightlines at which buildings were visually encountered were adapted to catch the attention of an ancient pedestrian.18 Doxiades was among the first in modern times to understand that ancient cities, and their sacred sites, were built with a mobile rather than a static viewer in mind, and his book is doing much to correct the common assumption that ancient buildings achieved their effects because their geometric proportions acted directly on the minds of viewers looking at them face-to-face, as if they were engravings printed in an architectural manual. However, by continuing to locate the site where meaning was made in the design of the building and its sightlines, rather than regarding acts of seeing and cognition as transactions that included the historically and culturally contingent expectations of viewers, Doxiades remained within the traditions of modern, object-centred, western art history.

As for the main viewing stations, although the ancient viewer arriving through the Propylaia would have had a clearer view of the west end of the Parthenon and of the stories presented there than was available from outside at ground level, he or she also knew that the main ceremonies took place at the eastern end of the Acropolis, and that the whole complex had been designed as an outdoor space where rites were performed. It was in the space between the east end of the Parthenon and the Erechtheion where the processions halted, where the culminating ceremonies occurred, and from where the processioners returned back through the Propylaia, and in some cases at least back along the peripatos before dispersing. The plentiful surviving descriptions and visual images of processions being performed in accordance with pre-arranged conventions and schedules, under the direction of leaders and marshals, suggest that the practices followed much the same general pattern for many centuries, before and after the classical period, until eventually being brought to an end or at least drastically reformed by the incoming Christian theocracy some time in the middle centuries of the first millennium CE.19 The main ancient ceremonies included animal sacrifice, skinning, roasting, and communal eating of the meat, accompanied by music made with instruments, singing, dance, and invocations of the gods.

Standing in the pivotal eastern area of the Acropolis summit, the participants were overshadowed, often literally, as the sun or moon moved, by the two main sacred buildings, the Doric Parthenon and the Ionic Erechtheion, the former with a frieze such as was more common on Ionic buildings, and the latter out-Ionianizing the buildings of Asian Ionia in the richness of the coloured glass and the ceramic beads with which it was bejewelled. This building was said to house the tomb of Erechtheus, so linking it to the myth of autochthony, and making it the earliest of the many tombs in the city and in the countryside where memory was officially deemed (‘nomismatized’) to be true, instituted, displayed, and occasionally performed.20

At the time the classical Parthenon and the other buildings on the Acropolis were being planned, the two main orders of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic, appear already to have already been separated; the Parthenon and Propylaia being Doric, the Erechtheion and the small Nike temple added later, being Ionic. The Parthenon was unusual in having a frieze, an Ionic feature, although this was not unique nor an innovation, as is sometimes suggested, since friezes had formed part of Doric buildings elsewhere, mainly in cities in Ionia in Asia and on some islands.21 And the ‘pre-Parthenon’ that was destroyed in the Persian invasions, and that later supplied some of the cut marble from which the classical Parthenon was built, or rather ‘rebuilt’, appears also to have included Ionic elements.22

Vitruvius, a Roman-era writer on architecture, in the Preface to his seventh book, recalling that the poet Zoilus, who had set himself up as a superior of Homer, and who, in the view of Vitruvius, had rightly been put to death for ‘parricide’ (in modern terms plagiarism) offers a long list of named predecessors who had written on architecture and on individual Doric and Ionic temples. Among these sources (Latin ‘fontes’, a word that retains its associations with water and fountains), which Vitruvius mentions that he has drawn on in making his compilation, is a work on the Parthenon written by its architectons, Iktinos, co-authored with an otherwise unrecorded Karpion.23 Whether this composition, of which no trace survives, was confined to the broad design and engineering of the building, or whether it also discussed its displayed stories, is not known.

By the classical period, it seems that each architectural order had its own recognizable visual characteristics: the Doric plain and solid, the Ionic lighter and more graceful. At some time not dated, each order had evidently been linked to myths of origin and to eponymous heroes, Doros for the Doric and Ion for the Ionic. Although the stories are only preserved in the work of Vitruvius, they appear to have been long established as components of a pan-Hellenic discourse and current at the time of the rebuilding programme. If so, the associations with the eponyms would have been present in the horizons that viewers brought to their seeing experience, acting—as was evidently a feature of eponyms—both as a mnemonic and a rhetoric, as has already been noted in the discussion of the interior of the building.

As for the main entrance at the east end of the Parthenon, only when the doors were opened, which may only have happened during festivals, perhaps as part of the culminating and concluding rites, was huge gold-and-ivory (chryselephantine) cult statue known as ‘Athena Parthenos’ visible only to a few people at a time, suggesting that processioners may have had to file past. The gold plates of that statue were designed to be detachable and therefore available to be useable, either uncoined or coined, as security for loans and guarantees denominated either in monetary or other terms. Both rooms of the Parthenon, therefore, served as strong-rooms for the most precious, and therefore the most at-risk material possessions of the city.24

When in use on collective festival occasions, the classical-era Acropolis was a place of bright and variegated colours to which participants contributed by their festival clothes, including wreaths and other markers of dress, some of which are likely to be the same as those shown mostly in two colours on ceramics and in full colour on the korai found in the nineteenth-century excavations. During the later classical period, when there were feasts or festivals every few days throughout the seasonal year, some at night, with many occurring in or near the Acropolis, there is a contemporary report that the east end was a place where grass grew, a remark which, if not just a euphemism for an area scuffed by human feet and animal hooves, may imply some cordoning and perhaps active watering and gardening.25

Stories Told in Stone

With so many claims on their senses, how did the processioners look at the stories offered on the buildings? The Ion of Euripides is unique among classical-era texts in presenting a scene of real viewers looking at a real pediment on a real building, albeit in a fiction.26 As with Pausanias, it was formerly customary to scold Euripides for not conforming to modern ways of seeing and their categories.27 Instead, I suggest, we can use the fictional scene and its place in the drama to recover a fuller understanding of the practice (‘praxis’) and of the conventions shared by producers and consumers, than any that can be yielded by modern art criticism. In a scene in the play set in Delphi, the chorus of women who are visiting as tourists make a direct reference to the west pediment of the temple to Apollo there, which shows one of the standard presentations on classical-era Hellenic temples including the Parthenon: a battle of giants (‘gigantomachy’). As a help to the audience of the play, as well as to later readers, the women declare at the start that some have looked at stories displayed on the buildings in Athens in the same way.28 The following is a translated extract from their conversation as presented by Euripides:

‘Look! come see, the son of Zeus is killing the Lernean Hydra with a golden sickle; my dear, look at it!

I see it. And another near him, who is raising a fiery torch— is he the one whose story is told when I am at my loom, the warrior Iolaus, who joins with the son of Zeus in bearing his labours?

And look at this one sitting on a winged horse; he is killing the mighty fire-breathing creature that has three bodies.

I am glancing around everywhere. See the battle of the giants, on the stone walls.

I am looking at it, my friends. Do you see the one brandishing her gorgon shield against Enceladus?

I see Pallas [Athena], my own goddess. Now what? the mighty thunderbolt, blazing at both ends, in the far-shooting hands of Zeus?

I see it; he is burning the furious Mimas to ashes in the fire.

And Bacchus, the roarer, is killing another of the sons of Earth with his ivy staff, unfit for war.’

Although the audience of the Ion is given only a short passage, which has been fitted into the tight conventions of the tragic drama, Euripides has packed in many aspects of the ancient classical experience that are not normally practised by modern viewers. For example, the women immediately recognize the stories from having heard them told aloud as they worked at their looms. They fly in their imaginations to Chalcidike at the northern border of the Hellenic world where the war of the giants had taken place in mythic times, and which was now a place of recent Athenian settlement. Looking and seeing are presented as social experiences, conversational, interactive, and interrogatory, with the different characters of the composition on the building picked out, recognized, and made to move at the behest of the viewers.29 As Katerina Zacharia has noticed, the women add details either from other compositions or from their own memories and imaginations.30 And since the Ionians in the settlements in the northern Aegean were known as Chalkidians, the classical-era audience was invited to see parallels between the imagined world of myth and that of their own day.31 To the women presented in Euripides’s play, the pediment of the building in Delphi, over which they rapidly move their eyes, was not a static piece of sculpture nor a ‘work of art’, but a set of coloured pictures packed with episodes, in this case mostly violent, that could be rearranged, added to, or subtracted from as they chose. Image and word were inseparable, and it was the women who collectively made the meanings.

A fragment of the Hypsipyle, a play by Euripides mostly lost, gives an indication of another of the ways in which the pictorial images on temples were encountered and used. As one of the characters declares: ‘Look – run your eyes up towards the sky, and take a look at the written reliefs on the pediment’.32 Although the lines have survived because they explain how the Greek word for ‘pediment’ was the same as that for ‘eagle’, they confirm features of the passage in the Ion, notably that looking at the pediments was an occasion for conversation, with no obligation to be hushed in reverence such as modern churches and museums enforce, and for the viewers to make and not just to receive meanings.

And there are other differences between the two ways of seeing offered in the two Euripidean plays. Besides drawing attention to the steep angle of viewing, the character, who is addressing the audience and not the other characters in the play, also makes clear that he sees the pieces as material manufactured objects, from which stories can be composed, as if in a play whose course is directed by the viewers. That some well-made images can be so like real life that a viewer cannot tell the difference is, of course, a rhetorical cliché found in much ancient as well as in modern writings. However, the more exact notion that static images are made to come alive in the imagination of the viewer is implied in a comment on the statues made by the mythic Daidalos reported by a later author, Diodoros of Sicily, who drew on earlier accounts and discursive conventions: ‘…they [the images] could see, they said, and walk and, in a word, they preserved so well the characteristics of the entire body that the beholder thought that the image made by him was a being endowed with life’.33

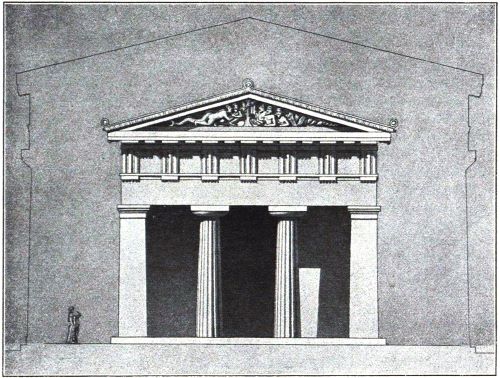

As for the most visible stories presented on the Parthenon, those displayed in the two pediments, they imply a transaction with the ancient viewer that is specific both to the medium and to the occasions on which encounters normally occurred. The nature of the composition is necessarily limited by the triangular shape of the architectural space that, in both cases, presents an identifiable central episode from local myth, namely scenes relating to the birth of Athena in the east pediment, and a contest between Athena and Poseidon in the west. The fullest visual record of how the two pediments appeared in modern times was made in 1674 when the encounter with the classically educated western visitors had just begun, and before the destructive bombardment by the Venetian-led western European army of 1687 and the subsequent fire; it is shown as Figure 1.34

The east pediment, shown at the top, had suffered more severely than the west underneath. The losses there, it now seems certain, had occurred when the Parthenon was adapted to serve as a Christian basilica with a Byzantine-style round-roofed apse at the east entrance, which took place at some time in the early centuries CE. In 1674 the western pediment was still largely complete, refuting later claims that the Ottoman Muslims, who at that time had controlled Athens for nearly two hundred years, deliberately destroyed figurative images as being inconsistent with Islam. Since, when the Ottoman forces first arrived in Athens in 1485, the Parthenon was a Christian church and was then to be converted into a Muslim mosque, it had benefited from the protection conferred on religious buildings by the millet system. The artist of the 1674 drawings, often referred to as Jacques Carrey although the attribution is doubtful, had prepared his record of the west pediment in chalk on two large sheets of paper, one for the parts under the apex on the viewer’s right and the other for those on the viewer’s left. When the two sheets were loosely joined, viewers of his work, and of copies of his work, were left with the impression that they were seeing a picture of the complete pediment.36

As for what the ancient producers of the west pediment intended to present to viewers, the tradition has been to rely on the brief remark by Pausanias that what was pictured was the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the land of Athens.37 And most scholars have accepted that what was shown was a stand-off in which Poseidon was the loser.38 However, even if Pausanias’s remark were to be taken to imply that the contest was about which of the two deities could claim the greater honour or which had been the first, the notion of a contest that produced a triumphant winner and a disgruntled loser cannot be easily squared with the discursive environment within which the design of the classical Parthenon was decided upon and built.39 There were plenty of offerings to Poseidon for his help in winning the sea battles of the Persian wars, both the immediate trophies by which after any battle the winner claimed victory, in this case dedications of wrecked enemy ships, and also permanent memorials built near the site. The remains of the classical-era temple dedicated to Poseidon on the promontory of Sounion still captures the attention of tourists and of ships at sea, and in Athens a shrine was set up to Boreas, the north wind that had disrupted the enemy’s ships off Cape Artemisium.40 It would be puzzling, incredible even, if, on the most often-seen story presented on the Parthenon, which is otherwise about promoting civic unity, inclusiveness, harmony, and mutual trust as the best way for the city’s success in warfare to continue, the contribution of Poseidon had been omitted or presented in unfavourable or grudging terms.

There is, however, no need to rely on the ambiguous testimony of the phrase by Pausanias. What the modern tradition has recently forgotten is that we have a description written around two hundred years before Pausanias by a much more authoritative ancient author. Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE), who had studied in Athens around the same time as Cicero, held a string of the highest public offices in the late Roman Republic, and his portrait appears on a coin of the time. Despite his having served as a military commander in the Civil Wars of Pompey against Caesar, he was appointed to supervise the public library at Rome and served on various governmental commissions. He was the author of numerous books, a few of which survive in whole or in part, mainly in the form of well-researched encyclopedias that were highly respected and frequently quoted.41 Varro’s explanation is to be preferred to that of Pausanias, not just because he wrote two centuries before and his account matches what we should have expected from the discursive environment, but because he had better opportunities for knowing what was intended. Instead of regarding Varro’s version as a later variant of Pausanias, Pausanias offers a variant of Varro, and an example of how, as in the Athenian tragic drama, the presented characters could perform more than one story, either advertently by a writer of plays, or in the minds of viewers listening to guides. A more elaborate version of the Varro fragment was offered by Aelius Aristides, in his Panathenaic oration in praise of Athens, one of the most formal of the occasions in which the official discourse was repeated, which is thought to have been composed around 155 CE, before Pausanias.42 Since Aristides repeats most of the components first heard in the classical period, his work in this instance, as elsewhere, can be taken as yet another example of the longevity of the discourse.43

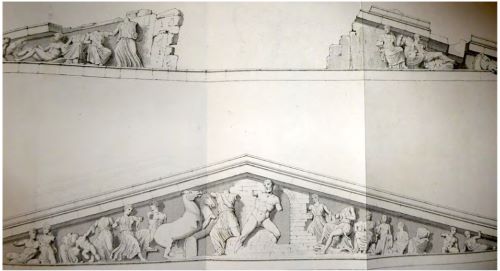

It now seems certain that some time before the chalk drawing was made, the centre of the composition was occupied by an image of an olive tree, picked out in painted marble or metal or some combination of the two. Indeed, since the image of the tree occupied what was, on normal as well as on festival days, the most prominent and most often-seen feature of the Parthenon, it may have been rendered in bronze or gilded bronze, making it a prime target for any thieves or mutilators who had the influence and infrastructure to be able to remove it. Low-denomination bronze coins made in Athens during the Roman imperial period often included views on prominent features to be seen in Athens.44 The example shown as Figure 2 can be regarded as part of the discursive environment, not only recording a famous feature of the cityscape but commending to its users the ideologies that it instantiated.

The mathematician Euclid, writing in the late fourth or third century BCE, but probably reporting observations made earlier, remarked that phenomena above eye level descend while those below ascend, something that the Commissioners are likely to have known about and might have chosen to build into the design and include in the contract with those commissioned to do the work.46 However that may be, what seems certain is that an olive tree was depicted in the space most often looked at on the Parthenon, immediately below the apex of the pediment, to which all eyes were drawn.47

The scene presented on a fourth-century water jar (hydria), which may be a direct allusion to the west pediment, shows the olive tree centred between the two divinities, with a flying figure with what looks like Victory (‘Nike’) in the upper apex, and a guardian snake curled round its lower trunk.48 The main features can be seen in the image at Figure 3, a flattened version of the composition prepared not long after the piece was excavated from a burial ground in the modern Crimea.

As was evidently the case on the west pediment, personages, divine and mythic, are shown on either side of the tree, arranged in groups in a variety of stances. Some pay attention to the central episode. Others are detached from the action and conversing. Some gaze directly at the viewer, inviting him or her to respond self-reflexively. And all, by their gestures and facial expressions, silently offer options to the viewer of how he or she might also choose to respond. They are mostly shown in attitudes of movement, of anticipation, of uncertainty, and of waiting for an event that lies in the future. As has been noted by Robin Osborne: ‘Pediments … manifest themselves to the viewer at once: any partial view is unstable: only the view of the whole can be satisfactory’.50 As characters from various, mainly local Athenian, myths, they have no reason for being together other than as components of a discursive environment unconcerned with realism, time, or place, displaying what was needed to enable the characters to be recognized and their stories re-energized by a classical-era Athenian viewer in accordance with conventions that ignored geography and chronology. As with all vase paintings that I know of that depict an ancient temple, it is as incidental to the main action as the temporary structures used as scenery in performances of tragic drama, to the extent that it is often impossible to say whether a real event is being pictured or an allusion to a play.

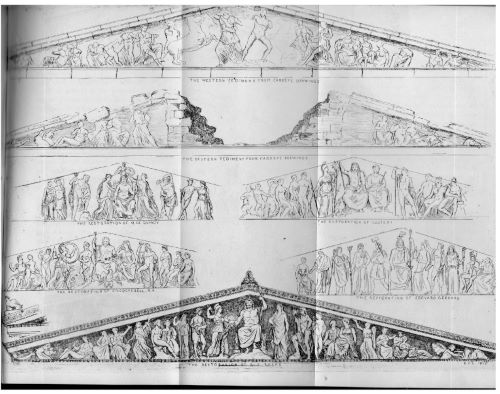

Many attempts have been made to identify the personages displayed, mainly by trying to reconstruct who might have been expected, or ‘deemed’, by the classical Athenians to have been present. However, that enterprise may rest on an assumption that the aim of the designers was to present an actual event, albeit telescoped. Figure 4 pictures a nineteenth-century attempt at reconstruction of the west and east pediments, partly to exemplify the wide variety of speculations offered, but also because it includes a version by Giovanni Battista Lusieri, Elgin’s artist and agent, republished here for the first time since 1845.51 The pictures do not sufficiently bring out the extent to which some of the characters presented are bursting out of their pedimental frame as a form of trompe l’oeil.

Since studies of ancient visual images have become detached from studies of ancient drama, and both from studies of the practices of ceremonial display and performance, the high degree of commonality between the repertories has sometimes been lost from sight. For example, of the four or five hundred tragic dramas of which the titles have been preserved in lists and mentions, all but a handful appear to take their characters from the world of myth. And we have an explanation that was widely circulated in the classical period. According to Herodotus, when The Fall of Miletus by Phrynichus, a prolific playwright, was first put on, and the audience wept with emotion, the author was heavily fined.53 Soon afterwards, at some time after 492, no plays that dealt directly with current or recent events appear to have been permitted. Of the many hundreds of tragedies performed in classical Athens, only three are known to have presented contemporary subjects.54 And we have an explanation of why a convention of excluding contemporary political questions from being directly discussed was introduced around 492 BCE.55 The decision on where to set the boundary may have followed the convention already adhered to in sacred buildings all over the Hellenic world.

Since the content of both storytelling media was approved in advance by the institutions of the city, including those who provided or authorized the financing, the outer boundaries of permitted deviation from the civic norms appear to have been patrolled. We also have the story of how Mikon, son of Phanomathos, a contemporary of Pheidias, a master in the making of both two- and three-dimensional images who was responsible for executing commissions in Athens (including some offered on the Theseion) was accused because, in an image of the Battle of Marathon, he presented the Persians as taller than the Athenians. Like Phrynichus, in the medium of the performed drama, the crime with which alleged offenders were charged was that of departing from the terms of contracts approved by the Athenian assembly.56

The same cohort of Athenian citizens might recently have been exhorted from the Pnyx by a gesturing Pericles or his reciter to uphold the civic values set out in stone, metal, paint, and fabric on the physical Acropolis. Since many were also frequent viewers of the tragic drama, it would have been impossible in practice to prevent the interpretation of the stories in stone from being influenced by those offered by the characters in the drama. One discursive medium interacted with the other, with the result that over the course of a typical lifetime of a classical-era Athenian, numerous myths were dramatized. Some existed in half a dozen versions; all explored general questions without explicit reference to topical political questions. The producers of tragedies were permitted to invent new mythic characters to appear alongside those in the familiar repertoire, and in at least one play, the Antheus by Agathon, said by Aristotle to have been successful, an entirely new myth was allowed.57

Looked at from modern times, a convention of excluding the immediately political may appear to be a censoring restriction, an aberration from the freedom that is often thought of as a normal prerogative of a ‘creative’ artist. However, seen from the perspective of an ancient classical writer conscious that he was making his contribution to a long-run moral development from brutishness, a decision to deploy the ancient myths in performance may have seemed like a democratic solution, building on the past while looking to the dialogic needs of the present and the future: exactly the kind of useful innovation that was central to Athenian imaginative self-construction.

What is probably the best representation of the west pediment, showing the olive tree as the central feature, was made in white plaster as a model for a full-scale work by the Viennese sculptor Karl Schwerzek in the late 1890s, as shown in Figure 5.

For his researches, besides talking with the leading scholars of the day, Schwerzek had visited the building and studied the detached pieces, including fragments held in museums elsewhere. In London he noticed that a fragmentary marble torso previously thought to have been a part of a metope had been carved in the round and it was reassigned to the west pediments.59 If, as there is no reason to doubt, images of children were included on either side of the central scene with the olive tree, it is likely that what were presented to ancient viewers were family groups, not individuals, making the myths that they were invited to actualize easier to recognize and to identify with. If, as is also likely, as consumers they shared with the producers a belief in extramission, they may have thought that their looking experience helped to make them heroic in accordance with Athenian civic ideology.

As far as the pediments are concerned, although it would have been hard for even the most antiquarian-minded ancient viewer to identify all the personages in the packed composition—even if, as is possible, there were words on the architrave or elsewhere—the fact that what was presented on the west pediment is a contest would have been plain to see even from a distance. And, since the actual viewerships of both media largely coincided, it would have been impossible in practice to prevent interpretations of the stories in stone from being influenced by those offered by the drama, and vice-versa. Indeed, far from the producers trying to keep the media separate, we have occasional evidence of how they were deliberately offered to ancient viewers as mutually supporting, as when, for example, the leader of the chorus of women in the Phoenician Women by Euripides compares herself to the golden statues to be seen at Delphi.60 Over the course of a typical adult male lifetime, and of those of some women and of other residents of the city too, few official ideologies were immunized against being converted into the more democratic conventions of dialogue.

Rather than thinking of the painted stone and metal figures presented on the pediments as statues fixed for ever in a historic moment like those photographed in a clicked moment by a still camera, it may be more fair to the ways of seeing recommended to ancient viewers to think of them as the assembled actors of a repertory company, already costumed, standing ready to perform (or already beginning) an old or a new play within a wide repertoire, whose broad scope was already familiar.61 Such plays could be composed either by the viewer himself or herself, as was the case of the women at Delphi on the Ion, or invented for a range of occasions by a playwright, orator, or leader of a festival. Indeed, the women presented in the Ionnot only make the images behave as actors in a play of their own making, but shrink the gap between themselves as viewers of the play and the players, so that they themselves become participants in the events that they are causing to unfold in their imaginations.62

With this way of seeing, there is no ‘correct’ nor ‘original’ version, nor any need for the plays to be speculatively arranged into a chronological sequence of development and divergence. Rather, I suggest, as with presentations on the tragic stage, the aim was to enable viewers to explore ideas within a genre they understood, and that needed only a few words of preface to remind the viewers of the characters and their mythic situation. To an extent every Athenian was encouraged to become his own dramatist, using the old stories not as a set of fixed texts that preserved quasi-historical information about the past but as an agenda for a not-yet-performed set of dialogic dramas of moral and political debate, many of which explored notions of civic ‘arete.’ Euripides, in particular, made plentiful use of the freedom that the conventions provided. In the Erechtheus, for example, the character of Athena demands that the character of Poseidon leaves Attica, having done damage enough with his earthquakes.63 The speech then offers what is tantamount to a commentary on the scene pictured on the west pediment of the Parthenon. By subverting the usual story that Athena and Poseidon were reconciled, the play can treat the static images as able to move and to develop in new directions, as in a new dramatic version of an old myth. In Euripides’ Ion, there are indications that the characters, by appealing to ‘pictures’, are presented as having those on the Parthenon in mind, or at least they could reasonably have been assumed to have done so by the ancient attendee.

Making the Mute Stones Speak: The Role of the Viewer

We have only a few recorded examples of how the ancient individual viewer was encouraged to release, to revivify, and, as in terms of ancient rhetoric, to ‘re-enargize’ the frozen figures; to make the mute stones speak; and to do so in new and sometimes in unexpected ways. Euripides imagined the conversations of the women looking at the pediment in Delphi on a special occasion. Under this way of seeing, which I will call ‘Every man (or woman) his own dramatist’, there is no ‘correct’ or ‘original’ version, nor need we attempt to recover a chronological stemma of commonality and divergence. As on the tragic stage, viewers are offered opportunities to explore ideas within a genre whose boundaries are understood, in which general questions are of greater importance than the characters who wrestle with them. Even in the brief phrase by Pausanias, one of the few real ancient viewers of whom we have records of his way of seeing, we can pick up this view, offered almost as an aside that scarcely needed to be mentioned, that the presentation is not one of a specific moment either before, during, or after an event. As George Mostratos translates Pausanias’s remark on the east pediment: ‘all the figures in the pediment over the entrance to the temple called the Parthenon relate to the birth of Athena’.64

Varro goes on to say that, in order ‘to appease his [Poseidon’s] wrath, the women should be visited by the Athenians with the three-fold punishment — that they should no longer have any vote; that none of their children should be named after their mothers; and that no one should call them Athenians.’65 This too is fully consistent with the discourse. As Nicole Loraux has pointed out, although there are words for ‘women of ‘Boeotia, Lacedaimon, Corinth, and other cities, usually formed with the suffix –issai- that puts their native city as central to their identity. Although, as we might translate, there were ‘Corinthiannesses,’ there were no ‘Atheniannesses.’66 The separation of gender roles between the polis for men and the oikos for women is advocated by both Plato and Aristotle, and by characters in the tragic drama. In the classical period the claim provided much merriment in the Lysistrata and the Birds of Aristophanes, we can take it that this feature of the official ideology was contested.67

Here, it may be worth noting the reported experience of one real visitor of the pre-First-World-War era when in Britain and elsewhere a political campaign for votes for women was at its height. Mrs. R. C. Bosanquet, wife of an archaeologist resident in Athens, and a classical scholar in her own right, remembered the version recorded by Varro. As she noted: ‘The vote was given on grounds of sex, the men voting for sea-power, the women for the goddess of wisdom and needlework. Then, as now, the women had the numerical majority and carried the business in hand. But the men had superior strength and punished the suffragatrices by the loss of the vote and otherwise’.68 In the second, post-war, edition of her book, when the aims of the women’s suffrage movement in Britain had been met in part, the story was omitted and, on the title page, Mrs Bosanquet now marked and aligned herself with the modest change in social and political attitudes by styling herself ‘Ellen. S. Bosanquet’.69

However, although the Varro version may appear to validate some notion of the equality of the sexes, it is undermined, or at least dialogically responded to, by the remark of the character of Apollo, speaking with the authority of a divinity who takes a special interest in Athens in the Eumenides of Aeschylus, first performed in 458 when the Parthenon was under construction but when all its features had probably already been decided upon. In asserting that women are not the real parents of children but only steward-nurses of embryos brought into being by a male impregnation, the character of Apollo cites, ‘as visible proof’ of his words, the fact that Athena is shown emerging from the head of Zeus, as on the east pediment, a statement of the official ideology and paideia of the classical city.70

The custom of producing new versions for new times continued long after the classical period, without anyone protesting that the true or original meaning had been misunderstood, subverted, or misappropriated. Aelius Aristides, in his Panathenaic oration of 151 CE—one of the formal occasions on which the asserted ideological continuity of the city was renewed—offered his audience a version such as Euripides might have dramatized. The struggle presented, he declared, was a warning against attempts at political coups by seizing the Acropolis. The mythic story had ended in a reconciliation, showing that it was better to use Athens’s tradition of courts and juries. As for Poseidon, presented on the pediment as the loser in the contest, that divinity had not, Aristides declared, ended his intense love for Athens, but had given her naval superiority in the wars of the classical period.71 In what has been called ‘visual theology’, that is, the practice of attempting to access the unseeable gods through images of the gods, Aristides exposes the endless circularity of the argument. Men make images of gods as they imagine them to be, he says, and then, by a reverse cognition, ‘deem’ them to be real and available to be invoked.72 It is tantamount to an admission that the gods are ‘nomismatic’ that is needed to hold together the officially commended belief system, but, like the nomisma of treating money as a thing and not a convention, it does not have to have any existence outside the decisions of those who collaborate in the deeming.

Endnotes

- In St Clair, William, Who Saved the Parthenon? A New History of the Acropolis Before, During and After the Greek Revolution (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2022) [hereafter WStP], Chapters 2 and 22.

- For example, several mentions in the works of Lucian of Samosata, some of which are best regarded as rhetorical exercises.

- Camp, John M., The Archaeology of Athens (New Haven: Yale UP, 2001), 52.

- In Chapter 2.

- The names were investigated by Schleisner, Steenberg, Brandes, and Heise, De Parthenone eiusque partibus (Hanover: Royal University publications, 1849), but doubts remain.

- That temples were places where ‘chremata’ were kept is implied by the remark by the character of Polymestor in the Hecuba of Euripides, Eur. Hec 1019. Although some anachronism in pushing back the invention of ‘money’ to the mythic time of the Trojan war (that is, around half a millennium before the Athenians themselves estimated the calendar date of the introduction of coinage) was perhaps acceptable in Athenian tragedy, the word is used to connote what is referred to elsewhere in the play as gold and silver.

- Discussed by Pedersen, Poul, The Parthenon and the Origin of the Corinthian Capital (Odense: Odense UP, 1989).

- Discussed by Harris, Diane, The Treasures of the Parthenon and Erechtheion (Oxford: OUP, 1995), with transcriptions.

- The ancient notion of ‘nomisma’ was discussed in Chapter 1.

- Summarized by, for example, Kallet, Lisa, Money and the Corrosion of Power in Thucydides (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 27–31 and 69–75.

- To be discussed in Chapter 4.

- Harris, Treasures of the Parthenon, no 372, item 373. χρυσίδιαδιάλι θασύμ μικταπ λινθίων καὶ τεττίγ ωνσ τα θμόντοὔτων.

- Noted by Hornblower, Simon, ed., Lykophron: Alexandra: Greek Text, Translation, Commentary, and Introduction (Oxford: OUP, 2015), 26.

- Summarised by Harris, Treasures of the Parthenon, 15–17.

- Aristoph. Cl. 768.

- Harris, Treasures of the Parthenon, 144, no 168. They also give a glimpse of how Athens had developed a system of mobilising and deploying the savings of the economy for the purposes of investment, normally as loan capital, notably for financing trade, agriculture, and manufacturing, with the resulting economic surplus diverted to other purposes, and that also could provide a rate of return to the city as lender, which in financial terms, if not defaulted on, seems to have been around twelve per cent per annum.

- The fact that, to the surprise of many visitors, the Parthenon was not visible from the Areopagus hill was discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 22.

- Doxiades, Constantinos A., Architectural Space in Ancient Greece, Translated and Edited by Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1972), especially the summary at 3–14. Based on the author’s 1936 dissertation published in 1937 as Raumordnung im griechischen Städtebau. Doxiades presented his ideas as a ‘discovery’ and as a general theory, based on ‘a natural system of coordinates’, that was itself ‘based on principles of human cognition’. His 1946 pamphlet on the damage done to Greece and its people during the Second World War was noted in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 23.

- Discussed, as far as the classical period is concerned, by Parker, Robert, Polytheism and Society at Athens (Oxford: OUP, 2005), which systematically collected and presented the evidence and on which all subsequent work is reliant.

- Discussed further in Chapter 4, that includes examples of real ancient viewers knowing explicitly that much of the built heritage was actively invented as a rhetoric.

- Discussed by Castriota, David, Myth, ethos, and actuality: official art in fifth-century B.C. Athens (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 226 with a map.

- Neils, Jenifer, The Parthenon Frieze (Cambridge; New York: CUP, 2001), 27.

- Vitr. Praef. 7.12.

- For completeness I note that there remains some doubt about the connotations of the various names and nicknames and it is possible that the hecatompedon was an adjoining building.

- In the Ion, the rocky slopes of the Acropolis beside Pan’s cave where the character of Kreousa alleges that she was made pregnant by Apollo are contrasted with the ‘green acres’ in front of the temples of Athena on the summit. στάδιαχ λοερὰπρὸ Παλλάδος ναῶν. Eur. Ion 497. Literally ‘stades’, a Greek measure of six hundred English feet, from which the modern word stadium is derived. The fact that the temples are in the plural tends to confirms that the character in the play is referring to the open ground at the east end of the Acropolis.

- It is difficult to infer much from the surviving lines and parts of lines of a satyr play by Aeschylus, called The Festivalgoers (Theoroi’), collected as Fragment 50, which include episodes of the satyrs looking at images of themselves displayed in a temple.

- For example: ‘…his description of the temple at Delphi, which is even worse arranged than is usual with him’. Verrall, A. W., ed., The Ion of Euripides, with a Translation into English Verse and an Introduction and Notes (Cambridge: CUP, 1890), xlvii.

- Eur. Ion 185 and following, not all of the text included in this excerpt.

- The marble fragments that were discovered in excavations are shown on the Perseus website: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/artifact?name=Delphi,+Temple+of+Apollo,+West+Pediment&object=Sculpture.

- Zacharia, Katerina, Converging Truths, Euripides Ion and the Athenian Quest for Self-Definition (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 15.

- Noted by Zacharia, Converging Truths, 3, referring to Thuc 4. 61. 2.

- Collard, C., Cropp, M. J. and Gibert, J., eds, Euripides, Selected Fragmentary Plays Volume II (Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 2004), Fragment 752c, page 186. At the risk of introducing a new ambiguity,I have amended the translation of γραπτοὺςτύπους from ‘painted reliefs’ offered by the editors to avoid being too definite. I do not wish to exclude the possibility that the phrase may refer to words that identified the characters for viewers, as they have been found on the Treasury of the Siphnians at Delphi, and may have existed elsewhere, including on the Parthenon where, on the pediments, a large number of local mythic characters are shown, not all of which are likely to have been recognizable by even local viewers without the help of words, either inscribed, or performed by procession marshals and tour guides.

- Diod. 4.76.2. According to Aristotle, a character in the lost Cyprians by Dicaeogenes, a fourth-century tragedian, weeps at the sight of an image. Noted by Wright, Matthew, The Lost Plays of Greek Tragedy, Volume 1, Neglected Authors (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 146, from Aristotle, Poetics 16, 1454b37–38, noting that ‘graphe’ may mean a piece of writing not a picture.

- Only a general impression of the appearance can be gained from the drawing made by Cyriac of Ancona in the fifteenth century, shown and discussed in, for example, Bodnar, Edward W., Cyriacus of Ancona and Athens (Brussels: Latomus, 1960).

- Included in A Description of the Collection of Ancient Marbles in the British Museum (London: British Museum, 1830), vi. Drawn by R. Corbould, engraved by H. Moses, published 8 November 1828.

- Omont. Frequently reproduced, for example in the fine edition by Bowie, Theodore and Thimme, Diether, eds, The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures (Bloomington and London: Indiana UP, 1971), and earlier by Michaelis, Leake, and others. Modern photographs of the full set of drawings are viewable on Gallica, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7200482m.r=.langEN, and a large selection in low resolution on Wikimedia Commons.

- ὁπόσα ἐντοῖς κα λουμένοι ςἀετοῖς κεῖ ται, πάνταἐ ςτὴνἈ θηνᾶςἔχει γένεσιν, τὰδὲὄ πισθενἡ Ποσειδ ῶνος πρὸςἈ θηνᾶνἐστινἔ ριςὑπὲρ τῆςγῆς. Paus. 1.24.5.

- For example: ‘One can hardly imagine a more fitting commemoration of Athena’s victory over Poseidon than the thrilling composition at the very center of the gable, where god and goddess meet in the heat of the contest’. Connelly, Joan Breton, The Parthenon Enigma, A New Understanding of the World’s Most Iconic Building and the People Who Made It (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 107.

- As restored in Chapter 2, including the explicit comment by the so-called Old Oligarch, Ps. Xen. Const. Ath. 4.6.

- The evidence is collected and discussed by Shear, T. Leslie, Jnr., Trophies of Victory: Public Building in Periklean Athens (Princeton, N.J.: Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University in association with Princeton UP, 2016).

- For example, Pausanias is referred to only once in the huge corpus of subsequent ancient writings, as noted in Georgopoulou, M., Guilmet, C., Pikoulas, Y. A., Staikos, K. S. and Tolias, G., eds, Following Pausanias: The Quest for Greek Antiquity (Kotinos: Oak Knoll Press, 2007), 19, whereas there are two volumes of fragments of Varro recovered from mentions in later authors, including many by Augustine.

- The date favoured by Trapp, Michael, ed., Aelius Aristides Orations. 1–2 (Cambridge, Mass and London: Loeb, 2017), 10.

- The character of Aspasia in the Menexenus recommends that olive trees be explicitly mentioned, Plat. Menex. 238a. She comes near to suggesting that Athena was named after the land of Athens as an eponym rather than that Athena conferred the name.

- Another, which showed the Acropolis and its caves, is shown as Figure 17.4 in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 17.

- Reproduced from Head, Barclay V., and edited by Poole, Reginald Stuart, Catalogue of Greek Coins: Attica-Megaris-Aegina (London: British Museum 1888), plate XVII. An example in good condition is photographed, with a description, by Kraay, C. M., The Coins of Ancient Athens (Newcastle: Minerva Numismatic Handbooks, 1968), viii, 3. Another version reproduced in Frazer, J. G., trans., Pausanias’s Description of Greece (London: Macmillan, 1898), ii, 300. Other examples, from various collections, noted by Beulé, E., Professeur de l’Archéologie à la Bibliothèque Impériale, Les Monnaies d’Athènes (Paris: 1858. Reprinted in facsimile by Forni of Bologna, 1967), 393.

- Noted by Tanner, Jeremy, ‘Sight and painting: optical theory and pictorial poetics in Classical Greek art’, in Squire, Michael, ed., Sight and the Ancient Senses (London: Routledge, 2016), 110, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719238. Tanner also refers to a fragment of a work by Geminus, a writer of optics of the first century BCE, which gives practical advice, such as presenting circles as ellipses and foreshortening rectangular elements, which are necessary when picturing buildings so that they appear to be symmetrical and ‘eurhythmic’. Discussed also by Senseney, John R., The Art of Building in the Classical World: Vision, Craftsmanship, and Linear Perspective in Greek and Roman Architecture (Cambridge: CUP, 2011), who offers examples of what the drawings for the Parthenon may have looked like.

- The desire of the designers to draw the eye upward to the key feature of the composition is also apparent on the central scene of the Parthenon frieze, to be discussed in Chapter 4.

- Dated c. 360–350 in the Hermitage, St Petersburg from excavations in Kerch. Described, with photographs in colour, in Cohen, Beth with contributions by Lapatin, Kenneth [et al.], The Colors of Clay; Special Techniques in Athenian Vases (Los Angeles, Getty, 2006), 339–341, https://www.getty.edu/publications/resources/virtuallibrary/0892369426.pdf. Cited by Connelly, Parthenon Enigma, 107. Reproduced in monochrome by Palagia, Olga, The Pediments of the Parthenon, second unrevised edition (Leiden: Brill, 1998), plate 10.

- Walters, H. B., History of Ancient Pottery: Greek, Etruscan, and Roman, Based on the Work of Samuel Birch (London: Murray, 1905), ii, opposite 24.

- Osborne, Robin, ‘Temple sculpture and the viewer’, in Rutter, N. Keith and Brian A. Sparkes, eds, Word and Image in Ancient Greece (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, Leventis Studies, 2000), 230.

- How it was obtained is not explained.

- Lucas, R. C., Sculptor. Remarks on the Parthenon: Being the result of studies and inquiries connected with the production of two models of that noble building, each twelve feet in length, and near six in width. The one exhibiting the temple as it appeared in its dilapidated state, in the seventeenth century, and executed from the existing remains, or from authentic drawings; the other, being an attempt to restore it to the fulness of its original beauty and splendour. Also, a brief review of the statements and opinions of the principal Writers on the subject: viz. Spon and Wheler, Stuart and Revett, Visconti, Quatremere de Quincy, Col. Leake, the Chevalier Bronsted, Professor Cockerell, Mr E. Hawkins, Professor Welcker, &c. ‘In the History of all Nations that have contributed to that greatness, and always adorning it; and in a commercial Nation, such as ours is, we may discern in the enlargement of Art an increase of our national prosperity (Salisbury: Brodie, 1845), opposite 46.

- Her. 6.2.

- Besides The Fall of Miletus, the exceptions are another play by Phrynichus called the Phoenician Women, and Aeschylus’s Persians that is dated to 472, and can be explained as a permitted exception.

- Herodotus 6.21. Frequently discussed, most recently and with the contexts most fully explored, by Wright, Neglected Authors, 17–27, http://doi.org/10.5040/9781474297608. The Phrynichus episode as reported by Herodotus, even if it simplified a process into a single event, also explains how the near contemporary Persians by Aeschylus passed the filters, and how both Phrynichus and Aeschylus in their numerous subsequent plays used stories from myth as comments on contemporary events and questions.

- This example, with others taken from rhetorical exercises, is given by Russell, D. A., Greek Declamation (Cambridge: CUP, 1983), 56.

- Aristot. Poet. 1451b.

- Photograph inserted in Schwerzek, Karl, Bildhauer, Erläuterungen zu der Rekonstruktion des Westgiebels des Parthenon (Vienna: Selbstverlag des Verfassers, 1896). Private collection.

- Noted by Smith, Cecil, ‘Additions to the Greek Sculptures in the British Museum’ in The Classical Review, Vol. 6 (10) (Dec., 1892), 475.

- Eur. Phoen. 220.

- That viewers who see either a real person who is standing still, or a [static] image of a real person, feel an urge to imagine them moving was noted by Plato in the Timaeus. Plat. Tim. 19b.

- Discussed by Zeitlin, Froma, ‘The Artful Eye: Vision, Ekphrasis, and Spectacle in Euripidean Drama’, in Goldhill, Simon, and Osborne, Robin, Art and Text in Ancient Greek Culture (Cambridge: CUP, 1994), 138–196.

- Euripides Erechtheus fragment 370 line 4 in Euripides, Selected Fragmentary Plays, Collard et al edition, i, 171.

- Paus 1.24.5. ὁπόσα ἐντοῖς κα λουμένοι ςἀετοῖς κεῖ ται, πάν ταἐ ςτὴνἈ θηνᾶςἔ χειγέν εσιν. Although Pausanias’ main interest was in collecting and systematizing the old stories, in describing how the ivory of the cult statue in marshy Olympia needed to be preserved with olive oil, in contrast with the ivory of the cult statue on the Athenian Acropolis that had to be kept damp with water, he mentions as an aside, as something that everyone knew, that the reason why the Acropolis has no water is because its great height keeps it dry, a scientific explanation that related both the phenomenon and the visual rhetorical presentation to the microclimate.

- Augustine of Hippo, On the City of God Against the Pagans, Book 18, Chapter 9. Again, the author is careful to enable the reader to separate his own voice, in which he offers his own opinions, from that of Varro, from whose work he quotes in support of his own. It seems likely that Augustine’s motive in riding on the authority of Varro was to help his own advocacy of the separation of gender roles that soon slipped into a claim that women were ‘by nature’ inferior.

- Loraux, Nicole, The Children of Athena, Athenian Ideas about Citizenship and the Division between the Sexes, Translated by Caroline Levine (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993), 153.

- Loraux, Children, 153.

- Bosanquet, Mrs R. C., Days in Attica (London: Methuen, 1914), 74. As an indication of the system of signs that Bosanquet shared with her expected readership, she described the land of Attica, at page 68, as ‘not much bigger than a medium-sized Scotch shooting’.

- Bosanquet, Ellen S., The Tale of Athens (London: Methuen, 1932).

- Aeschylus Eumenides, passage beginning at 656, and especially the phrase in line 663: τεκμήριονδὲτοῦδέσοιδείξωλόγου.

- Aristides, Panathenaic, 39, 42. I have amended Oliver’s translation to bring out more clearly that Aristides uses the word ‘eros’ that was normally reserved for sexual desire, and its use as a metaphor in describing the exchange implied by the prevalent theory of extramission. Oliver, James Henry, ‘The civilizing power: a study of the Panathenaic discourse of Aelius Aristides against the background of literature and cultural conflict, with text, translation, and commentary’ in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 58 (1) (1968), 1–223, https://doi.org/10.2307/1005987.

- The phrase ‘visual theology’ is from Israelowich, Ido, Society, Medicine and Religion in the Sacred Tales of Aelius Aristides (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 177.

Chapter 3 (165-192) from The Classical Parthenon: Recovering the Strangeness of the Ancient World, by William St Clair (Open Book Publishers, 08.04.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.