Lockwood rejected dependency, for herself and for other women, and did not hesitate to confront the male establishment.

By Dr. Jill Norgren

Professor Emerita of Government and Legal Studies

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

City University of New York

Introduction

“Discussions are habitually necessary in courts of justice, which are unfit for female ears. The habitual presence of women at these would tend to relax the public sense of decency and propriety.”

Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Ryan, In re Lavinia Goodell, 1875

In the years just after the Civil War, as women began joining the legal profession, only a handful of spirited applicants succeeded in breaking through the cultural barriers that made it difficult to train for the law or win bar membership. The law was still the domain of men. Most Americans felt that professional work “unsexed” or degraded women. Female brains, it was thought, were unfit for the strain of mental exercise. The hostility toward women with professional aspirations was so great that only the very brave pushed ahead.

Perhaps the bravest was Belva A. Lockwood.

At birth Lockwood had neither wealth and social standing nor the promise of a fine education. But eventually she would personally extract her law degree from the President of the United States, become the first woman admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court, and become a leader in the woman suffrage movement in the late nineteenth century.

Belva Lockwood was born on October 24, 1830, in the Niagara County town of Royalton, New York, the second daughter, and second of five children, of farmers Lewis J. and Hannah Bennett. Belva was self-made: she invented herself as a middle-class professional woman. By the end of the 19th century, after she had successfully lobbied for legislation to open the U.S. Supreme Court bar to qualified women lawyers and twice run as the presidential candidate of the Equal Rights Party, she had become one of the most well-known women in America.

Lockwood was a self-assured woman who exuded ego. She insisted on the right to prove herself, and she adopted bold positions in support of equal opportunity for women. At 22 she was widowed and left with a 3-year-old daughter. Refusing the traditional dependency of a widow, she separated from this child for nearly three years in order to attend college. Armed with her degree, she reclaimed her daughter and taught school in New York State before moving in 1866 to Washington, D.C. In the capital, she married Ezekiel Lockwood, an elderly war veteran with whom she had another daughter, a child who died before her second birthday. Lockwood soon found herself the primary breadwinner as her husband’s health failed. She later wrote life’s hard lessons into her public talks, repeatedly urging men and women to support the schooling of girls so they would not be dependent on others. Occasionally, she went so far as to say that women should not be permitted to marry before they could support a family.

Lockwood rejected dependency, for herself and for other women, and did not hesitate to confront the male establishment that kept women from voting and from professional advancement. She began practicing law in Washington only after fending off the “growl” of the young men of the National University Law School, who declared they would not graduate with a woman, and wringing her law school degree from the hands of President Ulysses S. Grant, the institution’s ex officio head, in 1873.

Three years later, in 1876, when the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court refused to admit her to its bar, stating, “none but men are permitted to practice before [us] as attorneys and counselors,” she single-handedly lobbied Congress until that body passed “An Act to relieve certain legal disabilities of women,” an effort that a reporter described as having required “an unconscionable deal of lobbying.” Lockwood agreed, writing later that to succeed, “nothing was too daring for me to attempt.” On March 3, 1879, on the motion of Washington attorney Albert G. Riddle, who had long been her champion, she became the first woman admitted to the Supreme Court bar, sworn in amidst “a bating of breath and craning of necks.” A year later, she argued Kaiser v. Stickney before the high court, the first woman lawyer to do so.

In 1884 Lockwood turned heads again when she became the first woman to run a full-fledged campaign for the presidency of the United States. Her third-party candidacy startled the country and vexed other suffrage leaders, some of whom thought her a “Barnum.” She believed that her bid for the presidency would help women gain the right to vote and to be accepted into partisan politics. She could not vote, she told reporters, but nothing in the Constitution prevented men from voting for her. She outlined a 12-point platform, later refined and presented as 15 positions on a broad range of policy issues including foreign affairs, tariffs, equal political rights, civil service reform, judicial appointments, Native Americans, protection of public lands, temperance, pensions, and the federalization of family law.

Local newspapers and the national press loved the story of a lady candidate. Puck, a mass circulation weekly known for its satiric cartoons, put “Belva” on one of its covers along with Greenback Party candidate Ben Butler. Lockwood financed her campaign by arranging to give paid speeches and even tried to arrange a debate with Grover Cleveland and James Blaine, the Democratic and Republican party candidates. She won fewer than 5,000 votes but was not discouraged. When she ran for the presidency for a second time in 1888, she told reporters, “Men always say, ‘Let’s see what you can do.’ If we always talk and never work we will not accomplish anything.” In an interview with a British journalist after the election, she argued that her second poor showing could be attributed to men who cling to “old ideas, developed in the days of chivalry” and rich, petted women. But she remained optimistic, saying, “After all, equality of rights and privileges is but simple justice.”

Beginning Law Practice

Lockwood had tremendous drive and the support of Ezekiel, her husband, who approved of her desire to rise in the world. She loved the fact that law was a man’s game and believed that it could be “a stepping stone to greatness.”

Lockwood opened a small law office out of her home even before she was admitted to the D.C. bar. Initially, she worked alongside Ezekiel. He had given up dentistry and was advertising as a notary public as well as a pension and claims agent. He also earned fees as a court-appointed guardian, overseeing the finances of minors and the mentally ill. He did not make a great deal of money in these endeavors, but they helped the family get by and opened doors for his wife. He was a gadfly, moving in and out of the local courts and federal agencies. In the small world of Washington, his name became known, and so did hers as she learned judicial and administrative procedure through copying and filing clients’ documents. He made the necessary connections to win letters of guardianship from the court. After securing a place for himself, he introduced his wife to officials and, by 1873, she was also earning fees as a court-appointed guardian. As an agent, Ezekiel also pursued land and treaty claims on behalf of Native American clients. This work opened yet another area of law to his wife.

Until 1875 the Lockwoods ran Belva’s practice out of their rooms at the Union League Hall in downtown Washington. Living there provided a convenient and inexpensive, if modest, home and office. The Union League was near the federal agencies where the Lockwoods filed their clients’ papers as well as the buildings that housed the District of Columbia courts. One of these was the local police court, whose sessions were convened at an old Unitarian church located at the corner of D and Sixth Streets, NW, three blocks from their rooms. Here people who otherwise knew Belva as an activist first took their measure of her as an apprentice attorney.

Police court proceedings provided the sleepy capital city with colorful diversion. In the early morning, people would gather at the old church building, waiting for the day’s session to begin. With a police force of 200 there were plenty of arrests—12,000 in 1873. Judge William B. Snell presided, hearing cases of drunkenness, stealing, swearing, and fighting. Although it was the last place to expect a proper middle-class woman, Lockwood had no qualms about entering Snell’s courtroom, perhaps because he welcomed her presence. While still in law school, in September of 1871, she had made her professional debut in front of him, when she won a reduction of sentence for an acquaintance who had been charged with drunkenness.

Minor police cases, probate work, and pension claims provided sufficient business that in 1873 Lura McNall, Lockwood’s surviving daughter, could advertise her mother’s apparent success in her Lockport Daily Journal news column: “The lady lawyer of Washington has quite an extensive practice, and a branch business and a lady partner in Baltimore.” Two months later Lura, well-schooled by her mother in public relations, wrote that this success “now seems beyond controversy as her office is daily and hourly filled with clients.” Against all odds, Lockwood had established herself as a solo practitioner.

The Lockwood law office drew a multiracial clientele of laborers, painters, maids, tradesmen, veterans, and owners of small real estate properties. The fact that Lockwood’s clients were largely working class undoubtedly helped in her success. As a woman, she would not have been able, in the words of a female colleague, to make “an extensive acquaintance among business men in an easy, off-hand way, as male attorneys make it in clubs and business and public places.” But if these male networks were denied to her, other channels existed, and she clearly used them to scout for clients. She represented people in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia and was always ready to travel longer distances. In August 1874 the Washington Evening Star reported that she had legal business in the Southwest: “Mrs. Lockwood, the lawyeress, leaves for Texas tomorrow, to be absent some forty days for the purpose of settling up the estate of the late Judge John C. Watrous, of that state, who died some two months ago in Baltimore. Judge Watrous was a large landed proprietor in southwestern Texas.”

A Full Practice

Lockwood’s goal was a competitive Washington-based legal practice. Initially, after her September 1873 admission to the District bar, she accepted cases that brought her before the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. Scholar Jeffrey Morris has described this court created by Congress as “an unusual hybrid” that was given most of the trial and appeals authority of other federal courts, while also hearing criminal and civil cases that elsewhere in America came before state and local courts. In her first year of licensed practice, she appeared nearly exclusively as plaintiff’s attorney in the law or the equity division of this court, a pattern that maintained itself to a lesser degree from 1874 to 1885.

Between 1873 and 1885 she was recorded as attorney in 100 equity court proceedings, while in the same period 75 law division listings carried her name. Half of her courtroom equity work involved divorce actions. As a woman attorney, she attracted female clients and represented wives as complainants against defendant-husbands. When she represented men in divorce actions, they were complainants, never defendants. After divorce actions, her most frequent equity work involved injunction proceedings, lunacy commitments, and actions requesting the partition of land. Much of her civil law work did not bring her to court and is not recorded in docket books. But like the other storefront lawyers of her day, in order to stay solvent, Lockwood worked up untold numbers of bills of sale, deeds, and wills.

The postbellum emphasis on gentility made the thought of women working in the criminal courts egregious, even loathsome. Society’s morally repugnant dramas played out in criminal court, a place off-bounds to ladies. Lockwood could have refused criminal cases. Yet, despite her religious rectitude and middle-class aspirations, criminal cases and criminal court argument were as acceptable to her as any other kind of legal work. It is not difficult to imagine this no-nonsense woman facing the judge in a room teeming with people, many of them down on their luck, charged with drunkenness or simple assault. Nor is it difficult to contemplate why the poor and the unfortunate had to accept representation by an inexperienced, woman lawyer. But Lockwood cut a sharp figure and was blessed with a quick mind and tongue. By 1875 she had begun to attract clients charged with more serious crimes, representation that brought her before the judges of the criminal division of the D.C. Supreme Court.

From 1875 to 1885 Belva represented at least 69 criminal defendants in this court. They were charged with virtually every category of crime from mail fraud and forgery to burglary and murder. She won “not guilty” decisions in 15 jury trials and submitted guilty pleas in 9. Thirty-one of her clients were judged guilty as charged, while five others were found to be guilty of a lesser charge. An entry of nolle prosequi (termination of the proceedings by the prosecutor) ended four cases. She won retrials for several others. She handled most of these cases on her own with only an occasional male co-counsel.

A House on Washington’s F Street

In 1875 the Lockwood family took rooms in a house at 512 10th Street, a block from the League Building and two doors down from the residence into which the mortally wounded Abraham Lincoln had been brought from Ford’s Theater. She conducted business in one or two of these rooms with Lura and Ezekiel nearby. Although increasingly frail, her husband continued to work as a notary public. His name and seal appear on many of the legal documents filed by his wife up through the month of his death in 1877.

Ezekiel died on April 25, in the midst of much legal business. The widow grieved but did not adopt deep mourning. Five days after his death, she was at her desk petitioning, by letter, for correction of an error in the assessment of a client’s taxes. Three months, later she purchased the house in which they had been living. The property at 619 F Street, NW, described by one visitor as “a very fine house,” cost slightly more than $13,000.

Lockwood bought the F Street house as a statement of now her solid middle-class professional status. Although it was not fancy, the 20-room house made an impression on visitors. In American Court Gossip, Mrs. E. N. Chapin told her readers that the lady lawyer’s brick home had nicely furnished parlours “with several good paintings to add their tribute to the lady’s taste.” Heavily mortgaged, it was undeniably a risky venture. But the purchase made good business sense. The building would be a home, a boarding house, an office, and a long-term investment. She would use the property as collateral on loans and business deals.

Belva’s daughter, Lura, and her niece, Clara Bennett, played important roles as Lockwood’s legal assistants. Lura’s life was tied tightly to that of her mother. She and her husband, Deforest Payson Ormes, lived at F Street, and she died there at age 44. Lura began clerking for Belva in 1873, one of several women and at least one man who, in the 1870s and 1880s, worked or studied with Belva for periods ranging from a few months to several years.

Sometimes Lockwood combined the business of law and the business of running a boarding house. In the summer of 1877, veteran James Kelly came to her law office hoping for help with a pension and a bounty claim. Kelly had been in the army since the 1850s, moving about the country. His wife was dead, and he had recently sent for his two daughters, who had been left in California in the care of Catholic nuns. The girls, Elizabeth and Rebecca, came east only to witness their father’s mental and physical collapse. By 1879 he required care in the Soldiers’ Home, and in February 1880 Kelly was “adjudged a lunatic.” A month later the court appointed Lockwood “committee of the estate” with power to collect and receive the pension money due him from the government. She was charged with the responsibility of furnishing him with necessities and of looking after his two daughters.

The Kelly daughters had come under Lockwood’s care even before her appointment as guardian, when James asked that she watch over and keep them from the streets. Rebecca arrived at F Street in January of 1880 and in court papers was described as 16. Lockwood disputed this fact, declaring that the two girls came to her wearing short dresses and “had not changed to maturity as women.” Lockwood later described Rebecca as “weak minded.” In exchange for room and board, her father’s account was charged six dollars a month, while the girl contributed occasional housework until 1883, when she went into service in Maine. Clara later testified that Rebecca never had regular tasks and could not be depended upon.

Rebecca’s older sister, Elizabeth, posed more of a problem. She, too, lived at F Street. Lockwood told a court that she was “too imbecile for self support.” She required constant supervision to keep her from vagrancy and importuning men. Neither of the girls won the hearts of anyone at the F Street home but its owner. Clara, adopted by her aunt and dependent upon her for a home, said with some exasperation that Belva would always bear with the girls, “defend and protect them because they had nowhere else to go, quite to the discomfort of other members of her family.” In fact, Clara reported, her aunt lost boarders who were not willing to put up with the girls’ bad conduct.

The children of Cherokee James Taylor proved easier when put in Lockwood’s care. Taylor, a lobbyist for the Eastern Band of Cherokee, first met the Lockwoods in 1875 at the 10th Street boarding house, where Mrs. Lockwood cultivated Taylor as a legal client. He gave her his personal legal business while they analyzed the more substantial problem of the Eastern Cherokee, who were negotiating for legal recognition and the right to file monetary, treaty-based claims with the United States Government.

Like James Kelly, Taylor realized that the lady lawyer could help with personal difficulties while taking care of his legal business. Also like Kelly, his trouble involved children who needed attention. Taylor made frequent trips to Washington and sometimes boarded at F Street. On one of these trips, he asked Lockwood to supervise two of his several children. She agreed, taking in John and Dora Taylor in the early 1880s, often for several months at a time. She charged the senior Taylor $15 a month for John, who took no meals, and $20 for the room and board of Dora. She looked after their schooling, bought their clothes, and when it was time for them to leave Washington, arranged for their travel to Indian Territory.

Lockwood’s bustling household was situated in the center of downtown Washington, a location that was neither quiet nor fashionable. But more important to Lockwood was the ease with which she could reach the local courts as well as the federal offices and chambers she visited as she expanded her claims, patent, and pensions practice. Until June 1879 the U.S. Court of Claims (the court in which individuals prosecute a claim against the government) occupied 12 rooms up the hill from her house, in the basement of the Capitol. In that year the court was relocated not far from her at 1509 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Her F Street home put her across the street from the Patent Office, which also housed the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with which Lockwood did business. Perhaps most fortunate for the Lockwood law firm was the selection of a site barely one block from her home for the new Pension Building, completed in 1887.

The 600 block of F Street was, in fact, a hub of legal activity. Washington’s legal tradepaper, The Washington Law Reporter, operated out of rooms at 633 F Street, NW, and several attorneys had offices on that block. Like Lockwood, they were eager to be near the buildings housing federal departments as well as the District courthouse.

In 1881 Lockwood shocked Washingtonians, who thought that riding was immodest for women, by acquiring an adult’s tricycle. Lockwood was not immodest. She was a practical 51-year-old woman, a health enthusiast who was comfortable with modern technology and unafraid of publicity. With resolute determination, she took up the tricycle, making herself fair sport for columnists. She rode several miles daily, going to federal departments, the Capitol, and the courts. Cycles were “freedom machines.” The head of the Lockwood law firm bought hers after seeing that the male attorneys who used them were completing their work more quickly.

Lockwood practiced law in the fashion of Washington men with small, street-level firms, her days a busy mix of clients, paperwork, and court appearances. A large number of her early civil cases consisted of the collection of debts from loans made, or money owed, for business transactions.

Clients suing for divorce were also a staple of her practice. In March of 1874, Lura wrote in her newspaper column that the divorce business was getting “very lively,” with Washington “likely to rival Chicago in this branch of the trade.” She was referring to the increased number of divorce petitions as well as a recent suspenseful case in which her mother outfoxed Frederick Folker, a postal employee, who was about to flee to California to avoid paying her client’s court-ordered alimony. Using a detective and application for a writ of exeat regno (“to restrain a person from leaving the kingdom”), Lockwood—described by Lura as “the lynx eyed attorney”—brought the court evidence of Folker’s refusal to pay and intended flight. The writ was issued and the ne’er-do-well ordered to give bonds for alimony and costs or go to jail.

As a woman, Lockwood always had to think about her image and used gentle forms of humor to soften the public’s view of her or to win a favor. When Lebbens Stockbridge brought a suit against her for $847 that he claimed to have placed in her hands as trustee, she reproached him in a 53-line rhyming poem that asked the court’s indulgence:

Oh! Cruel creditor thus to sue

For money charged as overdue,

And go into the Court and swear

To things as light as empty air;

And strive to get a judgment sum

Before the day of Judgment come;

You know I’d pay that little bill

Just as you fixed it in your Will . . .

She argued that Stockbridge had given her the money to hold for certain people “to whom she meant to leave it by will” but told the court that she would execute the trust.

She argued that Stockbridge had given her the money to hold for certain people “to whom she meant to leave it by will” but told the court that she would execute the trust.

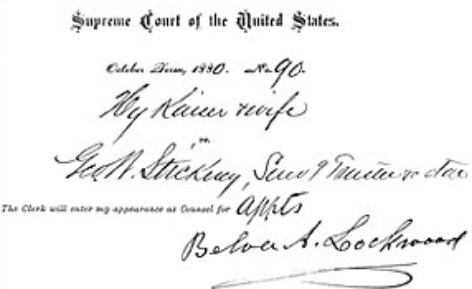

Lockwood made history as the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court of the United States. (Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, RG 267)

Most of the time, she was more restrained. Male attorneys in Washington considered her a proper colleague, and some shared case work. One of these collaborations, Kaiser v. Stickney, provided the opportunity for her first oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court, a quiet but historic appearance marking the first time that a woman member of the bar participated in argument.

The court heard Kaiser on appeal from the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia on November 30 and December 1, 1880. Lockwood was listed as counsel along with Mike L. Woods. The case involved the execution of a deed that bound local property for the payment of a debt. Lockwood had been lawyer for Caroline Kaiser, the appellant, since 1875. With some irony, she tried to use the much-criticized D.C. married women’s property laws to her client’s advantage by arguing that Kaiser, a married woman, could not legally be party to a contract that encumbered her own property. The strategy failed, and Kaiser was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which because of the District’s unique status, was the court that heard appeals from decisions of the D.C. Supreme Court.

Twenty-one months earlier, Lockwood had become the first woman member of the high court bar. Now she stood with Woods, who began their presentation with the same argument made before the D.C. court. He and Justice William Strong fell into a heated discussion of the law. According to the Evening Star, which gave the story front-page coverage, Lockwood rose at the conclusion of this exchange and asked to be heard. The justices agreed and she spoke for 20 minutes, giving her view of the case and, although she and Woods lost the appeal, making history.

“I have been now fourteen years before the bar, in an almost continuous practice, and my experience has been large, often serious, and many times amusing. I have never lacked plenty of good paying work; but, while I have supported my family well, I have not grown rich. In business I have been patient, painstaking, and indefatigable. There is no class of case that comes before the court that I have not ventured to try . . . either civil, equitable, or criminal; and my clients have been as largely men as women. There is a good opening at the bar for the class of women who have taste and tact for it.”

Belva A. Lockwood, 1888

Retirement Was Not for Her

If the docket books are to be trusted, Belva eased out of courtroom work in the mid-1880s. She did not refuse civil and criminal trial work—several dramatic cases lay in her future—but either the money was not sufficient, or her increasingly long trips as a public lecturer, a second career that she cultivated after her first presidential campaign, made it difficult to attract clients. In the place of trial work, Lockwood expanded her pension and bounty claims business, with Lura and Clara handling much of the paperwork. Lockwood later wrote that the office handled 7,000 pension cases from the 1870s through the 1890s. This was a respectable number although small in comparison with pension claims baron George E. Lemon, who told members of Congress that, just in the 15 years after the Civil War, his law firm had processed 50,000 filings and appeals.

In her 70s and early 80s, Lockwood balanced a career in law with tours on the lecture circuit and growing responsibilities as a member of the Universal Peace Union, a small pacifist organization. In 1906, in a multiparty case, she represented the Eastern Cherokee in their appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court. This time, unlike her appearance in Kaiser, she made a successful argument, and her clients shared in a multimillion dollar settlement. In 1912 she took on the last important case of her career, successfully representing Mrs. Mary E. Gage in lunacy proceedings, before a jury, that followed accusations Gage had threatened to kill prominent Washington banker Charles J. Bell.

A woman of great energy, at the age of 83 Lockwood led a group of women on a tour of Europe. Until her final illness, she was marching on the streets of the capital in support of woman suffrage and international peace. She died in Washington, D.C., in 1917 at the age of 86. Three years before, she had told a reporter that a woman might one day occupy the White House:

“It will be entirely on her own merits, however. No movement can place her there simply because she is a woman.”

Originally published by Prologue 37:1 (Spring 2005), the United States National Archives and Records Administration, to the public domain.