Underwater exploration in the medieval and early modern periods was never a single trajectory of progress. It was a patchwork of ideas, myths, experiments, and practices across the globe.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The sea has always presented humanity with a paradox. It is both pathway and barrier, a surface to be traversed and a depth to be feared. Medieval and early modern societies inherited from antiquity a fascination with what lay beneath the waves, imagining hidden realms, lost treasures, and potential technologies to extend human reach into the deep. Though full mastery of underwater navigation lay far in the future, the centuries between roughly 500 and 1700 witnessed both imaginative speculation and practical experimentation in submersion. Engineers, divers, and writers envisioned or constructed devices to extend breath, recover wealth, or wage war below the surface. These traditions were global, stretching from pearl divers in the Indian Ocean to Renaissance inventors in Europe.

Conceptual Foundations of Underwater Exploration

Classical Inheritance and Transmission

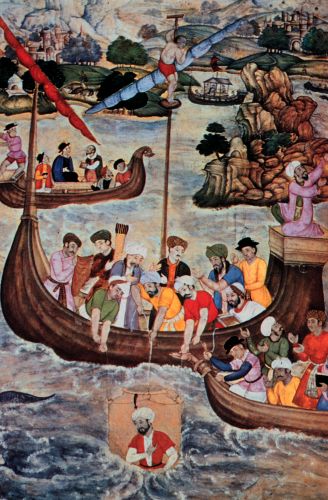

The classical world offered models of underwater ingenuity that medieval cultures absorbed and transformed. Aristotle1 described primitive diving bells that trapped air, allowing sponge divers in the Mediterranean to remain submerged longer.2 The legend of Alexander the Great descending into the sea in a “glass barrel” circulated widely, preserved in both Greek and later Arabic manuscripts.3 Such accounts were part myth, part speculative engineering, yet they framed the very possibility of submersion. In the Islamic world, scholars such as Al-Jazari adapted ancient mechanical knowledge, exploring hydraulic principles that could, at least theoretically, support diving apparatus.4

Medieval European Imaginations

Medieval Europe largely preserved such traditions in allegorical rather than practical form. The sea was portrayed in bestiaries as the realm of Leviathan, a place of peril and divine testing. Yet within monastic and scholastic manuscripts, hints of underwater devices appear, suggesting an ongoing fascination with the engineering challenges of respiration and pressure. Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis (1405) later illustrated apparatus for breathing underwater, reflecting both continuity of earlier ideas and new interest in technical warfare.5

Asian and Islamic Traditions

In South and East Asia, underwater exploration drew upon both myth and practice. Indian epic traditions mention divers retrieving jewels from the ocean’s depths, while Tamil sources celebrated pearl divers who braved considerable risk.6 In China, Song and later Ming texts described salvage operations for sunken cargo, sometimes using weighted diving techniques.7 In the Islamic maritime tradition, Ibn Khaldun noted both the economic significance of pearl fisheries and the ingenuity of coastal societies in exploiting them.8

Practical Applications: Diving, Salvage, and Warfare

Diving Bells and Salvage Operations

By the medieval period, diving bells were reported in use across Europe. The principle was simple: an inverted vessel trapped air, allowing divers to extend their time underwater. Salvage was the most common application, as sunken ships promised valuable cargo. In the Baltic and Mediterranean, records indicate organized attempts at recovery, often funded by merchants or governments eager to reclaim treasure.9 Similar practices existed in the Islamic world and in South Asia, where salvage complemented pearl fisheries as part of maritime economies.

Military and Covert Operations

Naval warfare occasionally turned to underwater methods. Byzantine sources speak of divers employed to sabotage enemy ships or cut anchor cables, while Venetian and Ottoman navies drew upon divers for reconnaissance.10 These operations were dangerous and limited, but they reveal recognition of underwater action as a strategic possibility. In Japan, ama divers, though primarily known for gathering shellfish and pearls, could be mobilized in times of conflict for underwater inspection and repair of vessels.11

Pearl Diving and Trade Economies

Far more significant in scale were the global pearl fisheries. In the Arabian Gulf, divers formed the backbone of an industry that by the early modern period provided immense wealth to coastal rulers.12 Japan’s ama divers, often women, sustained local economies through free diving traditions stretching back to antiquity.13 South Asian pearl fisheries, particularly in the Gulf of Mannar, generated revenue streams that attracted both Mughal patronage and later European colonial exploitation.14 Underwater labor here was not speculative fantasy but grueling economic reality, shaping societies and empires.

Early Modern Innovations in Design

The Renaissance Engineering Imagination

The Renaissance rekindled classical curiosity with technical precision. Leonardo da Vinci sketched underwater breathing devices, including masks with air tubes and designs for submarines.15 He warned, however, of their potential misuse in sabotage, reflecting anxieties about technology’s destructive capacity. Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis offered similar designs, placing underwater exploration within the broader context of military engineering. Al-Jazari’s earlier work on pumps and hydraulics may have informed these renewed efforts.16

First Experiments with Submersibles

The 16th and 17th centuries brought the first recorded attempts at actual submersibles. In England, William Bourne described a design for a boat that could be submerged by altering its volume, though it was never built.17 Cornelius Drebbel, a Dutch inventor working in London, constructed a functional submarine in the 1620s. Contemporary accounts state it was rowed beneath the Thames for over an hour, carrying passengers, a remarkable leap from myth to mechanism.18 Reports, albeit less substantiated, also suggest Ottoman and Mughal interest in similar devices.19

Navigation, Cartography, and Subaquatic Curiosity

The expansion of maritime empires sharpened the appetite for underwater technology. Portuguese and Spanish fleets sought methods to recover sunken treasure ships, while Dutch and English companies experimented with salvage to protect commercial investments.20 Early modern cartographers, meanwhile, began incorporating depictions of the sea floor and fantastic creatures, signaling both fear and fascination with the unseen depths.21

Cultural Meanings of Underwater Exploration

Theological and Mythological Frameworks

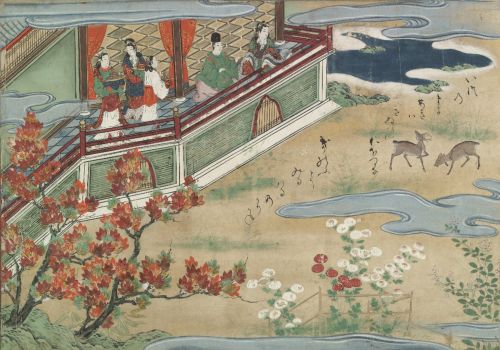

For many, underwater descent was less about mechanics than cosmology. Medieval Christian texts associated the deep with sin, chaos, and divine judgment, a space inhabited by monstrous creatures.22 In Japan, Shinto tradition described Ryūgū-jō, the palace of the Dragon King beneath the sea, accessible only to those chosen by fate.23 Islamic literature, including stories from One Thousand and One Nights, presented submerged realms filled with both peril and wonder.24 Such frameworks contextualized underwater exploration as encounters with the liminal and the sacred.

Science, Curiosity, and Humanism

Yet alongside theology, humanist curiosity reframed submersion. Renaissance readers revisited Aristotle and Alexander with renewed seriousness, interpreting their underwater experiments as empirical rather than mythical.25 The humanist ethos of probing nature’s secrets encouraged engineers and natural philosophers to see the ocean not as an impenetrable void but as a frontier for investigation. Submersion thus became a metaphor for intellectual daring, mirroring the drive to chart new worlds above the waves.

Case Studies Across the Globe

Europe: Venetian and Hanseatic Salvage; Leonardo da Vinci; Drebbel’s Submarine

European waters teemed with sunken ships, making salvage an urgent concern. Venetian records describe organized diving operations, while Hanseatic ports along the Baltic invested in equipment to recover lost cargo.26 Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches reveal both imaginative scope and practical attention to materials. Cornelius Drebbel’s submarine, tested on the Thames under the patronage of James I, stands as the most dramatic early modern realization of underwater transport.27

Islamic World: Al-Jazari; Arabian Pearl Diving; Ottoman Naval Divers

In the Islamic world, Al-Jazari’s mechanical treatises of the 12th–13th centuries preserved hydraulic knowledge crucial to breathing devices and pumps.28 The Arabian Gulf pearl trade bound coastal economies to underwater labor, producing both wealth and human suffering. Ottoman naval records, meanwhile, mention divers employed in sieges and maritime defense, situating underwater practice within imperial strategy.29

South Asia: Pearl Fisheries of Tamil Nadu and the Gulf of Mannar; Mughal Patronage

The Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka sustained one of the richest pearl fisheries of the medieval and early modern periods. Tamil sources and later European travelers described fleets of divers descending without apparatus, their lungs trained by generations of practice.30 Under the Mughals, revenue from these fisheries was integrated into imperial finance, showing how underwater labor could sustain terrestrial empires.31

East Asia: Japanese Ama Divers; Chinese Salvage Traditions

Japan’s ama divers harvested abalone, seaweed, and pearls, their practice rooted in both economic necessity and cultural symbolism.32 They became emblematic of resilience and connection to the sea. In China, Song and Ming records describe salvage of sunken goods, with divers using weighted stones to descend and primitive air supply methods to extend their time.33 These traditions underscore the continuity of underwater economies in East Asia.

Americas: Indigenous Pearl Diving and Spanish Exploitation

With Spanish conquest, indigenous diving skills in the Caribbean and Venezuela were redirected toward colonial exploitation.34 Enslaved laborers, often coerced, supplied pearls for European markets, linking underwater labor to the Atlantic economy. Reports from Spanish officials describe the extreme mortality of divers, reflecting the brutal conditions of submersion under duress. In this context, underwater exploration reveals the darker intersections of technology, empire, and exploitation.

Conclusion

Underwater exploration in the medieval and early modern periods was never a single trajectory of progress. It was a patchwork of ideas, myths, experiments, and practices across the globe. From pearl fisheries sustaining empires to da Vinci’s sketches and Drebbel’s Thames submarine, humans probed the depths with both imagination and ingenuity. These endeavors embodied the intersection of commerce, warfare, and wonder. Though full mastery awaited later centuries, the medieval and early modern worlds laid the conceptual and practical foundations for underwater exploration, inscribing the depths into humanity’s expanding horizon of discovery.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Aristotle, Problemata, trans. Hett (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), 913b.

- Ibid., 914a.

- Richard Stoneman, Alexander the Great: A Life in Legend (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 45–47.

- Donald R. Hill, Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology (London: Ashgate, 1998), 122–26.

- Konrad Kyeser, Bellifortis, ed. Bert S. Hall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969), 201–05.

- Osmund Bopearachchi, “Ancient Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu: Maritime Trade” in South-Indian Horizons, eds. Jean-Luc Chevillard and Eva Wilden, Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2022, 539-551.

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 483–86.

- Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 374–76.

- Gluzman, Renard. “Notes on Venice’s Ship-Breaking Industry and the Scrap Market in the Sixteenth-Century.” The Journal of European Economic History No. 2, September 2018, 84-85.

- Alexander Kazhdan, The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 642–43.

- Andi Cross, “The Ama: Freediving with Japan’s Last Sea Women,” Oceanographic, accessed September 2, 2025.

- Frauke Heard-Bey, From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates (London: Longman, 1982), 41–44.

- Cross, The Ama.

- Sinnappah Arasaratnam, Maritime India in the Seventeenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 118–24.

- Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Atlanticus, fol. 27r–28v.

- Hill, Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology, 145–47.

- William Bourne, Inventions or Devises (London: 1578), 62–65.

- John Protasio, “Evolution of the Submarine,” Warfare History Network, October 2012.

- Giancarlo Casale, The Ottoman Age of Exploration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 93–95.

- Arasaratnam, Maritime India, 131–34.

- Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 217–21.

- Peter Dendle, Satan Unbound: The Devil in Old English Narrative Literature (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 167–69.

- Carmen Blacker, The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan (London: Allen & Unwin, 1975), 84–86.

- Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nights: A Companion (London: Tauris, 1994), 142–45.

- Stoneman, Alexander the Great, 99–102.

- Law, “Salvage and the Venetian Economy,” 97–102.

- Reuleaux, “Drebbel’s Submarine,” 216–18.

- Hill, Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology, 130–33.

- Casale, The Ottoman Age of Exploration, 96–97.

- Rajan, Ancient Maritime Traditions of Tamilakam, 91–96.

- Arasaratnam, Maritime India, 121–22.

- Boroditsky, Ama Divers, 33–39.

- Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, 488–91.

- Kris Lane, Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas, 1500–1750 (New York: Routledge, 1998), 57–61.

Bibliography

- Arasaratnam, Sinnappah. Maritime India in the Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Aristotle. Problemata. Translated by Hett. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936.

- Blacker, Carmen. The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan. London: Allen & Unwin, 1975.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Ancient Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu: Maritime Trade” in South-Indian Horizons, eds. Jean-Luc Chevillard and Eva Wilden. Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2022, 539-551.

- Cross, Andi. “The Ama: Freediving with Japan’s Last Sea Women.” Oceanographic, accessed September 2, 2025.

- Bourne, William. Inventions or Devises. London, 1578.

- Casale, Giancarlo. The Ottoman Age of Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Davies, Surekha. Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Dendle, Peter. Satan Unbound: The Devil in Old English Narrative Literature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- Gluzman, Renard. “Notes on Venice’s Ship-Breaking Industry and the Scrap Market in the Sixteenth-Century.” The Journal of European Economic History No. 2, September 2018, 83-95.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke. From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates. London: Longman, 1982.

- Hill, Donald R. Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology. London: Ashgate, 1998.

- Ibn Khaldun. The Muqaddimah. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

- Kazhdan, Alexander. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Kyeser, Konrad. Bellifortis. Edited by Bert S. Hall. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Lane, Kris. Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas, 1500–1750. New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Leonardo da Vinci. Codex Atlanticus. Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- Protasio, John. “Evolution of the Submarine.” Warfare History Network, October 2012.

- Stoneman, Richard. Alexander the Great: A Life in Legend. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.