The modern history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict resists finality. It is a story saturated with memory, loss, and competing visions of justice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Geography of Memory and the Politics of Return

The modern Palestinian-Israeli conflict is often narrated through headlines, policy briefs, and episodic bursts of violence. Yet its historical roots stretch deep into the late Ottoman era, and its unfolding is inseparable from European colonialism, nationalist awakenings, and the collapse of old imperial orders. What emerged in the twentieth century was not merely a dispute over land but a contest between competing national visions, both shaped by trauma, exile, and the longing for political self-determination.

To recover the conflict’s historical texture, we must examine four overlapping periods: its origins in the late nineteenth century, its gestation during the British Mandate (1917–1948), its transformation through the 1947–48 civil war and partition, and its entrenchment in the aftermath of successive wars. Here I offer a layered account of that trajectory, centering on demography, ideology, and the haunting durability of competing historical claims.

Zionism, Ottoman Decline, and the Seeds of Conflict (Late 19th Century)

The roots of the conflict lie not in the formal creation of Israel in 1948, but in the prior century, when the ideologies of Zionism and Arab nationalism were beginning to crystallize. In the late nineteenth century, Palestine was a peripheral province of a waning Ottoman Empire. It was inhabited primarily by Arabic-speaking Muslims, with significant Christian and Jewish minorities. This population, largely rural and agricultural, had long lived in a loosely integrated society marked by religious coexistence, punctuated at times by localized tensions but not systemic violence.1

Into this space, European Zionism emerged as both a secular national movement and a response to antisemitism. Theodor Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (1896) provided a secular, political framework for Jewish self-determination, rooted in the conviction that Jews could not assimilate safely in Europe.2 For many early Zionists, Palestine was not only a religious symbol but a practical solution. Immigration began in waves (aliyot) from Eastern Europe, with the First Aliyah (1882–1903) marking the beginning of modern Jewish settlement in the region.3

Jewish immigrants often purchased land from absentee Ottoman landlords, displacing Arab peasants in the process.4 While these purchases were legal, they inaugurated a process of economic and social transformation that disrupted local village life and sowed the seeds of resentment. Jewish settlers, influenced by European socialism, often formed exclusive agricultural communes, which reinforced separation rather than integration with the local Arab population.5

Still, in these early years, tension did not yet erupt into large-scale violence. Palestinian identity, while emerging, remained largely local and regional rather than explicitly national. It was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the imposition of British colonial rule that gave sharper political form to both Zionist ambition and Palestinian resistance.

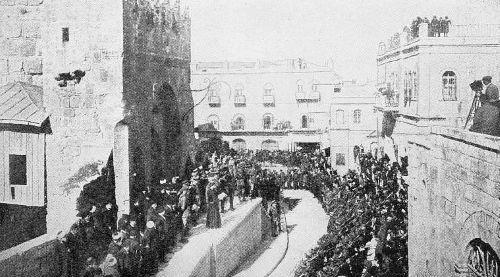

The British Mandate and the Transformation of National Space (1917–1948)

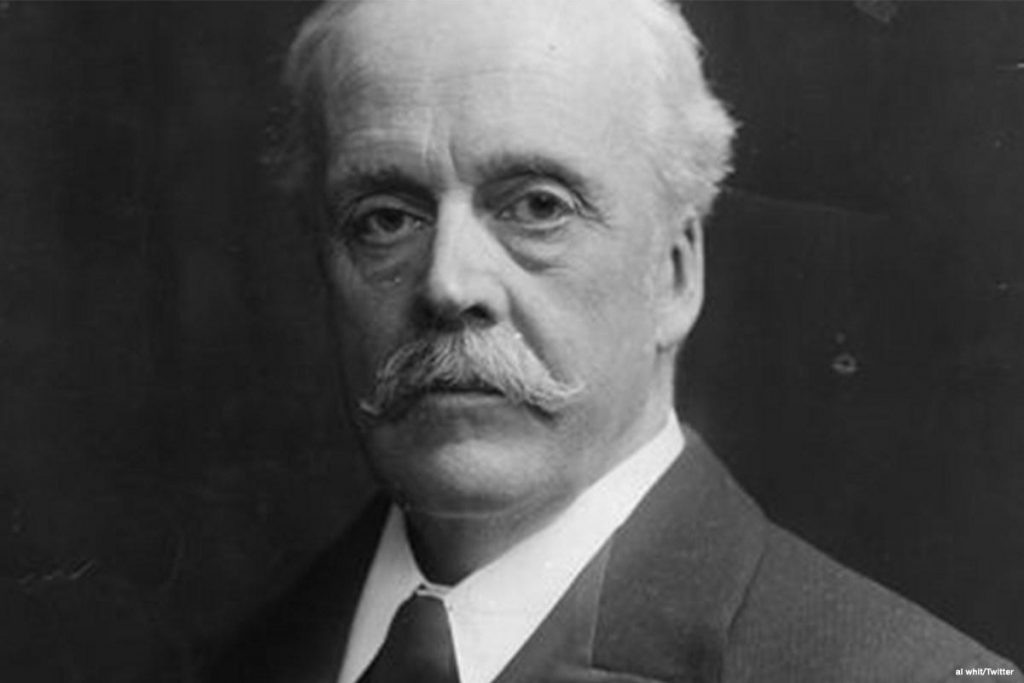

The Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Britain expressed support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, marked a decisive rupture. It placed British imperial interests at the center of a deeply asymmetrical arrangement. Palestinian Arabs, who formed the majority population, were offered no equivalent political promise.6 Britain thus became the custodian of a contradictory mandate: to promote Jewish national aspirations while also safeguarding the rights of the indigenous Arab population.

Jewish immigration surged during the interwar period, particularly in the wake of pogroms in Eastern Europe and later under the threat of Nazi persecution. Between 1919 and 1939, the Jewish population in Palestine grew from approximately 10 percent to nearly 30 percent of the total, changing the demographic and economic landscape dramatically.7 The influx of capital, expertise, and institution-building contributed to the emergence of a modern Jewish polity-in-formation, complete with schools, labor unions, defense forces, and political parties.8

For Palestinians, this transformation was experienced not as modern development but as existential threat. The 1920s and 1930s saw increasing episodes of violence, culminating in the 1936–39 Arab Revolt against both British rule and Zionist immigration. The British response was brutal, involving mass arrests, village curfews, and the execution of Palestinian leaders.9 The revolt was crushed, but its aftermath was long-lasting. Palestinian political institutions were shattered, and the Arab leadership was driven into exile or silence.

Britain, attempting to appease both sides, oscillated between support for Zionist goals and half-hearted concessions to Arab demands. The 1939 White Paper, which restricted Jewish immigration in the face of rising Arab opposition, came too late to prevent catastrophe. As the Holocaust accelerated in Europe, Palestine became both a symbolic and literal refuge, but the gates were closing. For Zionists, British constraint appeared as betrayal. For Palestinians, it was still not enough. The Mandate had become untenable.

Partition and Civil War: The Shattering of Coexistence (1947–48)

The United Nations’ 1947 Partition Plan proposed the division of Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab, with Jerusalem as an international zone. Jews, who at the time made up one-third of the population and owned less than 7 percent of the land, were allocated 55 percent of the territory. Palestinians, the majority, viewed the plan as illegitimate and refused its terms.10

Violence erupted almost immediately. Between November 1947 and May 1948, civil war consumed Palestine. Jewish militias, such as the Haganah and the more radical Irgun and Lehi, carried out coordinated military operations to secure the territory allotted by the UN plan—and often beyond. Arab resistance was fractured and locally organized, with little central command.11

The pivotal event of this period was the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” in which more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes.12 While Israeli historians long maintained that this exodus was voluntary or provoked by Arab radio broadcasts, a growing body of archival research shows that in many cases, Palestinian villages were deliberately emptied and destroyed to prevent return.13 The infamous Deir Yassin massacre in April 1948, in which over 100 villagers were killed by Irgun forces, sent shockwaves through the Palestinian population and intensified flight.14

On May 14, 1948, the State of Israel was declared. The next day, neighboring Arab armies invaded, triggering the first Arab-Israeli war. Israel not only survived but expanded its territory beyond the UN partition boundaries. Palestine, as a political entity, ceased to exist. The West Bank was annexed by Jordan, and Gaza came under Egyptian control. But for Palestinians, the trauma of dispossession would remain an open wound.

War and Repetition: The Cementing of Conflict (1948–1973)

The period following the 1948 war saw the conflict metastasize from a national to a regional dimension. Israel’s victory was hailed as miraculous by its supporters, but it also entrenched a military ethos and siege mentality that would shape its politics for decades. Within the new state, Palestinians who had remained were granted citizenship but lived under military rule until 1966, subject to land seizures and political surveillance.15

The Arab states, meanwhile, were humiliated by the defeat, but they lacked a coherent strategy. The 1956 Suez Crisis, in which Israel, Britain, and France attacked Egypt after Nasser nationalized the canal, demonstrated the fragility of Western control in the region. Although Israel withdrew under U.S. pressure, it had shown itself to be a regional power capable of acting unilaterally.

The turning point came in 1967. In the Six-Day War, Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. This not only reshaped the map but brought over one million Palestinians under direct Israeli military occupation.16 The occupation inaugurated a new phase of the conflict, characterized by settler expansion, administrative control, and international legal ambiguity.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War, launched by Egypt and Syria to regain lost territories, briefly punctured Israeli confidence but ultimately reaffirmed its military dominance. In the wake of these wars, a new political dynamic began to take hold. The Palestinian national movement, exiled and reconstituted as the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), emerged as the primary voice of Palestinian identity. Armed struggle became its method, international recognition its goal.

Conclusion: History in the Present Tense

The modern history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict resists finality. It is a story saturated with memory, loss, and competing visions of justice. For Israelis, the establishment of the state represented both redemption and necessity, forged in the shadow of genocide. For Palestinians, it marked a moment of catastrophe that continues to unfold in refugee camps, military checkpoints, and diplomatic stalemates.

To understand this history is not to resolve it. But it is to see more clearly what remains contested. The conflict was not born of ancient hatreds or religious inevitabilities, but of modern ideologies colliding in a land whose meaning was both sacred and strategic. Each chapter built upon the silences of the last.

As historians, our obligation is not to adjudicate the politics of the present but to illuminate the choices of the past. In those choices—made by empires, settlers, rebels, and refugees alike, we may find the contours of a tragedy that was never inevitable, and a future that remains unwritten.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 48–51.

- Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State, trans. Sylvie d’Avigdor (London: David Nutt, 1896), 25–26.

- Anita Shapira, Israel: A History (Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2012), 6–9.

- Gershon Shafir, Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1882–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 73–76.

- Ilan Pappé, A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 54–57.

- Efraim Karsh, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 287.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–1999 (New York: Vintage, 2001), 137–40.

- Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate (New York: Henry Holt, 2000), 212–15.

- Charles D. Smith, Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013), 167–69.

- Avi Shlaim, The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (New York: Norton, 2000), 22–23.

- Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 75–78.

- Nur Masalha, The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (London: Pluto Press, 2003), 7–10.

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld, 2006), 108–110.

- Morris, 1948, 209–11.

- Shira Robinson, Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 34–36.

- Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal, Palestinians: The Making of a People (New York: Free Press, 1993), 242–44.

Bibliography

- Herzl, Theodor. The Jewish State. Translated by Sylvie d’Avigdor. London: David Nutt, 1896.

- Khalidi, Rashid. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- Karsh, Efraim. Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Kimmerling, Baruch, and Joel S. Migdal. Palestinians: The Making of a People. New York: Free Press, 1993.

- Masalha, Nur. The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem. London: Pluto Press, 2003.

- Morris, Benny. 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- ———. Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–1999. New York: Vintage, 2001.

- Pappé, Ilan. A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- ———. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford: Oneworld, 2006.

- Robinson, Shira. Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- Segev, Tom. One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate. New York: Henry Holt, 2000.

- Shafir, Gershon. Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1882–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Shapira, Anita. Israel: A History. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2012.

- Shlaim, Avi. The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. New York: Norton, 2000.

- Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.