Black activists have long used maps to help illustrate their communities’ history and to document historical injustices.

By Dr. Joshua F.J. Inwood

Professor of Geography

Senior Research Associate, Rock Ethics Institute

Penn State

By Dr. Derek H. Alderman

Professor of Geography

University of Tennessee

Introduction

When historian Carter Woodson created “Negro History Week” in 1926, which became “Black History Month” in 1976, he sought not to just celebrate prominent Black historical figures but to transform how white America saw and valued all African Americans.

However, many issues in the history of Black Americans can get lost in a focus on well-known historical figures or other important events.

Our research looks at how African American communities struggling for freedom have long used maps to protest and survive racism while affirming the value of Black life.

We have been working on the “Living Black Atlas,” an educational initiative that highlights the neglected history of Black mapmaking in America. It shows the creative ways in which Black people have historically used mapping to document their stories. Today, communities are using “restorative mapping” as a way to tell stories of Black Americans.

Maps as a Visual Storytelling Technique

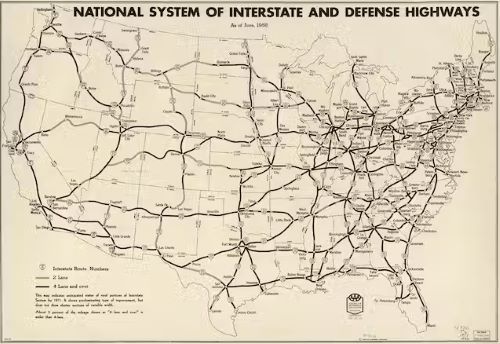

While most people think of maps as a useful tool to get from point A to point B, or use maps to look up places or plan trips, the reality is all maps tell stories. Traditionally, most maps did not accurately reflect the stories of Black people and places: Interstate highway maps, for example, do not reflect the realities that in most U.S. cities the building of major roads was accompanied by the displacement of thousands of Black people from cities.

Like many marginalized groups, Black people have used maps as a visual story-telling technique for “talking back” against their oppression. They have also used maps for enlivening and giving dignity to Black experiences and histories.

An example of this is the NAACP’s campaign to lobby for anti-lynching federal legislation in the early 20th century. The NAACP mapped the location and frequency of lynching to show how widespread racial terror was to the American public.

Another example is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s efforts to document racism in the American South in the 1960s. The SNCC research department’s maps and research on racism played a pivotal role in planning civil rights protests. SNCC produced conventional-looking county-level maps of income and education inequalities, which were issued to activists in the field. The organization also developed creative “network maps,” which exposed how power structures and institutions supported racial discrimination in economic and political ways. These maps and reports could then identify urgent areas of protest.

More recently, artist-activist Tonika Lewis Johnson created the “Folded Map Project,” in which she brought together corresponding addresses on racially separated sides of the same street, to show how racism remade the city of Chicago. She photographed the “map twins” and interviewed individuals living at paired addresses to show the disparities. The project brought residents from north and south sides of Chicago to meet and talk to each other.

Maps for Restorative Justice

Restorative mapping is an important part of the Living Black Atlas: It helps bring visibility to Black experiences that have been marginalized or forgotten.

An important example of restorative mapping work comes from the Honey Pot Performance, a collective of Black feminists who helped create the Chicago Black Social Culture Map, or the CBSCM. This digital map traces Black Chicagoans’ experiences from the Great Migration to the rise of electronic dance music in the city . The map includes historical records and music posters as well as descriptions of important people and venues for that music.

While engaging Black Americans in the effort, the CBSCM map tells the story of Chicago through a series of artistic movements that highlight African Americans’ connection with the city.

After years of gentrification and urban renewal programs that displaced Black people from the city, this project is helping remember those neighborhoods digitally. It is also inviting a broader discussion about the history of Black Chicago.

Restoring a Sense of Place

An important idea behind restorative mapping is the act of returning something to a former owner or condition. This connects with the broader restorative justice movement that seeks to address historic wrongs by documenting past and present injustices through perspectives that are often ignored or forgotten.

The CBSCM map is not a conventional paper map. While it includes many things you would find in such a map, such as road networks and political boundaries, the map also includes links to fiction writing and the Chicago Renaissance, art and music, as well as expressions of food, family life, education and politics that document a hidden history of Black life in the city. The map provides links to specific historic documents, socially meaningful sites, and to the lives of people that tell the story of Black Chicago.

Thus, the map helps highlight how this geography is still present in Chicago in archives and people’s memories. Through this digital representation of Black Chicagoans’ deep cultural roots in the city, the mapping aims to restore a sense of place. Such work embodies what Black History Month is about.

Originally published by The Conversation, 02.05.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.