When Captain John Bacon fell in 1783, he took with him the last embers of Loyalist resistance in New Jersey and the final illusion that the American Revolution had been a war of clear moral boundaries.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

As the American Revolution waned and peace negotiations unfolded across the Atlantic, the woods and marshes of southern New Jersey still echoed with the sharp crack of musket fire. There, long after organized armies had laid down their arms, men like Captain John Bacon refused to surrender to the calm of a war’s end. Known among Patriots as “Bloody John Bacon,” he commanded a band of Loyalist irregulars called the Pine Robbers, an assemblage of soldiers, deserters, and opportunists who haunted the Pine Barrens, preying on the vulnerable amid the chaos of a nation not yet born.1

Bacon’s story, though rooted in local violence, belongs to a larger history of civil fracture that accompanied the Revolution’s closing years. The Loyalists who remained active after Yorktown were not simply clinging to a lost cause; they were living in a world without clarity, one where allegiance and survival intertwined in the shadows. In the pine wilderness between Monmouth and Ocean Counties, Bacon’s men raided farms, robbed travelers, and attacked Patriot detachments. Some called it vengeance. Others called it murder. The line between the two grew thinner with each raid.2

The most infamous of these episodes came in October 1782, months after the last great battle of the war, when Bacon’s men ambushed a group of militiamen salvaging a grounded vessel off Long Beach Island. Twenty-one men were killed in what would later be remembered as the Long Beach Island Massacre, a grim reminder that ideology and brutality were often indistinguishable in the Revolution’s twilight.3 The slaughter shocked even those accustomed to frontier warfare and triggered a relentless manhunt that would culminate months later with Bacon’s own death at the hands of Patriot pursuers in a tavern near Cedar Bridge.4

What made Bacon’s brief but bloody career remarkable was not merely his violence but what it revealed about the Revolution itself. In the pine wilderness, the struggle for independence had devolved into something less orderly and more personal, a civil war within a civil war. Bacon and his gang embodied the social disintegration that often follows political upheaval: men left unmoored by a fading empire, clinging to vengeance and plunder as the only certainties left. This essay traces their rise and fall to illuminate the messy afterlife of revolution, when the ideals of liberty gave way to the reckoning of survival.

Background: John Bacon’s Origins and the Pine Robbers

The story of Captain John Bacon begins not with a professional soldier but with a tradesman shaped by the unforgiving economy of the New Jersey coast. Before the Revolution, Bacon worked as a shingler and laborer in Monmouth County, a region where loyalties were as divided as its landscape of farms, forests, and salt marshes. The coming of war fractured those fragile communities, pitting neighbor against neighbor. In that chaos, men like Bacon found purpose and protection in Loyalism, but also opportunity in violence. His turn from shingler to raider was less a single act of treachery than a slow descent into the moral twilight that civil conflict so easily creates.5

The Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey (vast, sandy, and sparsely populated) offered refuge to deserters, outlaws, and Loyalist irregulars alike. The tangled thickets and hidden trails formed a perfect natural fortress from which bands could strike Patriot settlements and vanish. Bacon was not the first to exploit this landscape. The so-called “Pine Robbers” had emerged earlier in the war as a loose confederation of raiders, sometimes organized under Loyalist officers, sometimes acting as common thieves. Their operations blurred distinctions between legitimate Loyalist resistance and sheer banditry. By 1780, Bacon had risen among their ranks, commanding a small but notorious contingent that used intimidation, robbery, and murder to assert Loyalist vengeance against the new republic’s supporters.6

The Loyalist cause in New Jersey had long been complicated by geography and divided sentiment. Coastal towns such as Shrewsbury and Toms River hosted both Patriot militias and Tory sympathizers, while the interior woods became havens for those fleeing reprisal. The war’s irregular nature there (characterized by raids, arson, and ambushes) was not simply military; it was domestic. Bacon’s group reflected the social fragmentation of these borderlands. Many of his followers were displaced Loyalists, but others were criminals drawn by plunder. They robbed travelers, looted farmsteads, and occasionally traded stolen goods through sympathetic merchants still loyal to the Crown.7

The Patriots, in turn, responded with their own brutality. County militias pursued the Pine Robbers relentlessly, sometimes killing suspects without trial. Each skirmish deepened local hatred and erased distinctions between justice and revenge. Within this vicious circle, Bacon’s name began to circulate as both specter and symbol, an outlaw whose actions reflected the Revolution’s unresolved contradictions. To Loyalists, he was a defiant remnant of a just cause; to Patriots, he was the embodiment of treachery itself. His notoriety would reach its height in the violent years between 1780 and 1782, when his raids transformed local feuds into tragedies still remembered in New Jersey folklore.8

Bacon’s Campaign of Raids, 1780–1782

By 1780, Bacon had transformed from a figure of local defiance into the scourge of southern New Jersey. The collapse of organized Loyalist military strength in the region left a vacuum that men like him were eager to fill. As British troops withdrew to urban strongholds and Loyalist outposts dwindled, Bacon’s band found itself operating in a lawless frontier where neither side maintained full control. Their raids struck both economic and psychological blows, designed as much to terrify as to enrich. Patriots called them “murderers and thieves,” but for Bacon and his men, the raids were acts of retribution, punishments dealt to a rebellious population that had betrayed its king.9

The earliest recorded killings attributed to Bacon’s command occurred near Cranberry Inlet in December 1780, where his men ambushed a small militia patrol, killing Lieutenant Joshua Studson and several others.10 Witnesses later reported that the victims were stripped of their clothing and possessions before their bodies were left to the coastal scavengers, a gesture both brutal and symbolic, marking the dead as traitors in Loyalist eyes. Bacon’s operations were swift and precise, often targeting isolated patrols or supply wagons. He knew the pine woods intimately, using the narrow “causeways” that threaded through the marshes to strike and disappear before reinforcements could arrive.11

By late 1781, Bacon’s notoriety had spread through Ocean and Monmouth Counties. His raid on Manahawkin became infamous after a skirmish there left several local militiamen wounded and the town’s stores pillaged. The Patriots retaliated with sweeping manhunts that netted more innocents than criminals, feeding a cycle of vengeance that blurred moral boundaries on both sides. These actions came at a time when the Revolution itself was fracturing under fatigue: Yorktown had been won, but the social and political wounds of civil conflict remained open. In New Jersey’s pine country, that meant the war continued, less as a struggle for independence and more as a bitter reckoning between neighbors.12

Bacon’s tactics reflected both cunning and desperation. He moved at night, avoided direct confrontation, and relied on an intricate network of Loyalist sympathizers who provided food and information. Some reports suggest that Bacon’s men disguised themselves as Patriot militia to approach targets without suspicion, while others described them as ghostlike figures emerging from the pines with blackened faces to obscure recognition.13 Their raids were calculated performances of terror, intended to assert Loyalist presence long after the British military had lost its grip. In the waning months of 1782, Bacon seemed less a soldier of the king than the embodiment of a lingering rebellion against the very idea of American authority.

By the fall of that year, his campaign would culminate in one of the war’s last and most infamous atrocities, the massacre at Long Beach Island. Yet even before that bloodletting, Bacon’s name had become legend across coastal New Jersey. Parents invoked it to frighten children; Patriots swore vengeance upon it. He had become the Revolution’s phantom in the pines, neither wholly political nor entirely criminal, a remnant of the Crown’s fury surviving in the wilderness.14

The Long Beach Island Massacre (October 1782)

The war for American independence was effectively over by the autumn of 1782. Negotiations in Paris had begun months earlier, and the guns of Yorktown had long fallen silent. Yet along the sandy coast of southern New Jersey, the violence refused to die. On October 25, 1782, Bacon led his Loyalist band in what became known as the Long Beach Island Massacre, a final convulsion of the Revolution’s brutality. The victims were a detachment of Patriot militiamen and privateers who had salvaged cargo from a grounded British vessel near the inlet. To Bacon, such property was Crown prize; to the Patriots, legitimate spoil. The argument ended in gunfire.15

The encounter began when Bacon’s men surrounded the unsuspecting salvagers in the predawn darkness. Witnesses later described the attack as swift and merciless. Outnumbered and unprepared, the Patriots were cut down where they stood. Contemporary reports from The New-Jersey Gazette and local correspondence record between nineteen and twenty-one deaths, with several others wounded or taken prisoner.16 The attackers seized what remained of the ship’s goods (rum, cloth, and small luxuries) and vanished into the pine wilderness before the nearest militia could respond. That morning, the surf rolled over the blood of men who had believed the war already won.

News of the massacre spread quickly through the coastal counties, provoking outrage and fear in equal measure. The brutality of the killings, occurring after open hostilities had ceased, struck many as proof that the Revolution’s end had not yet reached New Jersey’s shadowed corners. Governor William Livingston denounced the act as “wanton murder” and authorized renewed pursuit of all known Pine Robbers.17 For local families, however, justice mattered less than survival. Patriot sympathizers abandoned isolated farms; Loyalists concealed their allegiances in silence. The Revolution’s ideology had thinned into mere endurance.

The massacre also crystallized Bacon’s myth. To Loyalists still hiding in the woods, he was a defiant captain who refused to yield to the rebels’ victory. To Patriots, he became a spectral menace, proof that treachery had outlasted treaty. Folklore soon embroidered the tale with superstition: Bacon’s ghost was said to haunt the beaches where the tide had washed away his victims, and travelers spoke of hearing phantom musket fire over the dunes.18 Yet behind those legends lay a grim political truth, the war’s final violence had been turned inward, fought not between nations but among neighbors who would share the same fragile peace.

In the wake of Long Beach Island, the pursuit of Bacon intensified. Militia patrols scoured the Pine Barrens, burning suspected safehouses and hanging collaborators without trial. Still, Bacon proved elusive, aided by Loyalist sympathizers who fed and sheltered him in secret. Each failed expedition deepened the militia’s fury, transforming their hunt into vengeance. The massacre had become both symbol and scar, ensuring that reconciliation would come to New Jersey more slowly than to any other colony.19

Cedar Bridge Skirmish and Final Pursuit (December 1782 – March 1783)

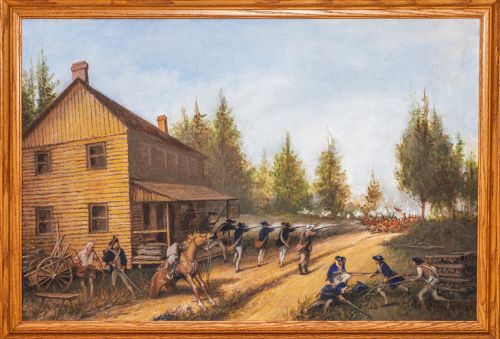

In the winter following the Long Beach Island massacre, John Bacon’s reign of fear began to close upon itself. The Patriot militia, hardened by months of frustration, mounted a concerted campaign to flush him from the pines. Their opportunity came on December 27, 1782, when Bacon’s band was spotted near Cedar Bridge Tavern, a remote outpost straddling the sandy causeway between Barnegat and Little Egg Harbor. A detachment of Burlington County militia under Captains Richard Shreve and Edward Thomas surrounded the tavern, trapping the Pine Robbers inside. What followed was a brief but violent exchange remembered as the Affair at Cedar Bridge.20

Accounts differ on who fired first. Some witnesses claimed Bacon’s men opened fire from the tavern’s windows, while others insisted the militia initiated the attack. For nearly half an hour, shots echoed through the cold pines until smoke filled the structure and the Loyalists fled under cover of confusion. When the gunfire ceased, four men lay dead and several others wounded. Bacon himself escaped into the swamps, reportedly wounded but still carrying his musket.21 The Patriots had won the skirmish in tactical terms, yet Bacon’s survival ensured his legend endured. To his pursuers, he was becoming something less human, a phantom conjured by the war’s unfinished hatreds.

The manhunt that followed stretched into the first months of 1783. With peace negotiations nearing conclusion, Bacon’s survival embarrassed Patriot officials eager to declare the state pacified. Governor Livingston renewed rewards for his capture, while local newspapers published detailed descriptions of his height, features, and supposed hiding places.22 Bands of militia scoured the woods, often terrorizing innocent farmers accused of harboring the outlaw. Still, Bacon slipped through their fingers, sustained by a dwindling network of Loyalist sympathizers and a terrain that had always served him better than any army could.

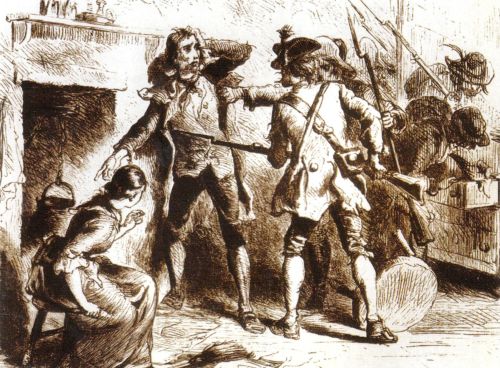

The end came not in a battle but in a tavern. In March 1783, a small party of militiamen led by Captain John Stewart tracked Bacon to the home of a Loyalist sympathizer near West Creek. When ordered to surrender, he reportedly drew his musket and fired, wounding one of the soldiers before being shot and bayoneted in return.23 His body was carried into the yard and buried without ceremony. Some accounts claim the victors paraded his corpse through neighboring towns as proof that the “Terror of the Pines” was dead at last. Whatever the manner of his death, it marked one of the final killings of the Revolution in New Jersey, a fittingly brutal epilogue to a war that had long ceased to distinguish vengeance from victory.

In the years that followed, Bacon’s name drifted from the realm of history into that of folklore. The tavern at Cedar Bridge became a monument to the Revolution’s lingering violence, and the Pine Barrens retained their ghost stories of musket flashes on moonless nights. For historians, however, Bacon’s death closed the final chapter of Loyalist resistance in the state.24 His downfall symbolized the exhaustion of a civil conflict that had pitted neighbors against one another long after nations made peace, a grim reminder that revolutions rarely end when the treaties are signed.

Interpretation: Loyalist Guerrilla, Outlaw, or Both?

To understand John Bacon is to confront the moral murk of civil war. His defenders, few though they were, insisted that he remained a soldier of the king, fighting on principle against a rebellion that had fractured lawful order. His detractors, far more numerous, described him as a marauder who cloaked greed and cruelty in the language of loyalty. The truth likely lies somewhere between those poles. By the final years of the Revolution, the boundaries between Loyalist partisanship and criminal opportunism had dissolved in the pine forests of New Jersey. Bacon’s raids, though carried out in the name of the Crown, bore little resemblance to organized warfare. They were personal, improvised, and sustained as much by vengeance as ideology.25

The Pine Robbers themselves embodied this collapse of discipline. Some, like Bacon, had once served in Loyalist units under British command; others were deserters, smugglers, or men displaced by confiscations and reprisals. The Revolution had stripped them of livelihoods, property, and legitimacy, leaving only violence as a means of survival.26 Their story blurs the neat dichotomy of Patriot versus Loyalist that dominates popular memory. In truth, the New Jersey frontier was less a theater of noble causes than a landscape of reprisals, one where loyalty could change with hunger or fear. Bacon’s persistence after Yorktown reveals how the Revolution’s ideological clarity gave way to local vendetta and social breakdown once the broader war subsided.

In the eyes of the new American government, Bacon’s death marked justice served; in the memory of many Loyalists, it symbolized martyrdom. Both interpretations distort the deeper reality that his violence was born of dislocation, not devotion. His raids were not acts of strategy but symptoms of a society tearing itself apart.27 He stood as the dark mirror of the Revolution’s ideals, an emblem of how freedom’s birth can spawn chaos where authority once reigned. In that sense, Bacon was not merely a Loyalist gone rogue but a casualty of transformation itself, caught between a dying empire and an unsteady republic.

Historians have since debated his legacy. Some cast him as a relic of Loyalist resistance, others as a regional bandit elevated by legend. Yet his life resists simplification. Bacon’s story reminds us that the American Revolution, often celebrated as a clean break from tyranny, was in many places a fratricidal war whose scars lingered long after independence was declared.28 His end closed the book on New Jersey’s last Loyalist campaign, but the questions he left behind (about allegiance, justice, and the price of victory) echo still among the whispering pines.

Conclusion

When Captain John Bacon fell in 1783, he took with him the last embers of Loyalist resistance in New Jersey, and the final illusion that the American Revolution had been a war of clear moral boundaries. His life and death reveal the Revolution not as a clean passage from tyranny to liberty but as a grinding struggle that corroded communities from within. In the Pine Barrens, where the pines muffled sound and the marshes concealed movement, political conviction had long ago blurred into survival. Bacon’s raids, his notoriety, and his violent end form the anatomy of a conflict that outlasted itself, a civil war that persisted in the minds and fears of those who had lived through it.29

The story of the Pine Robbers, like that of Bacon himself, forces a reckoning with the Revolution’s forgotten landscape. While cities celebrated independence and diplomats drafted treaties, the backwoods of New Jersey remained contested ground. Here, the war’s ideals dissolved into vendetta. Every raid, reprisal, and execution reminded survivors that victory had not delivered order but only a new hierarchy of power. In that shadow, Bacon’s ghost lingered—not merely as a legend of violence but as a symptom of the young republic’s unfinished peace.30

Yet even in death, Bacon became a kind of cultural barometer. Local lore cast him alternately as villain and victim, the last Loyalist outlaw whose restless spirit haunted the pine wilderness. Later generations, eager for distance from the Revolution’s chaos, mythologized him into a folk figure, proof that the republic had triumphed over its own darkness.31 But beneath the folklore lies the enduring question his life posed: how do revolutions end for those who cannot belong to what follows? Bacon’s defiance was not heroic, yet it was undeniably human, a reflection of the dislocation that shadows every great upheaval.

In the centuries since, the pines have reclaimed his trails, the taverns have weathered to silence, and the bloodstained sands of Long Beach Island have turned to legend. Still, John Bacon remains an unsettling presence in the story of American independence, a reminder that freedom’s dawn was not born in harmony, but in the tangled woods where loyalty, desperation, and vengeance shared the same breath.32

Appendix

Footnotes

- Monmouth County Historical Association, “The Death of John Bacon,” accessed November 2025.

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon: The Last of the Jersey Pine Robbers,” Journal of the American Revolution (2021).

- Revolutionary New Jersey, “Long Beach Island Massacre,” accessed November 2025.

- All Things Liberty, “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers,” accessed November 2025.

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, New Jersey (Bayonne, NJ: E. Gardner & Son, 1890), 243.

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon.”

- Encyclopedia of New Jersey, ed. Maxine Lurie and Marc Mappen (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 622.

- Monmouth County Historical Association, “The Death of John Bacon.”

- Journal of the American Revolution, “Captain John Bacon: The Last of the Jersey Pine Robbers,” 2021.

- All Things Liberty, “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers.”

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 247.

- Monmouth County Historical Association, “The Death of John Bacon.”

- Encyclopedia of New Jersey, ed. Maxine Lurie and Marc Mappen, 623.

- Revolutionary New Jersey, “Long Beach Island Massacre.”

- Revolutionary New Jersey, “Long Beach Island Massacre.”

- The New-Jersey Gazette, October 30, 1782, archival reprint via Monmouth County Historical Association.

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 250.

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon.”

- All Things Liberty, “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers.”

- Monmouth County Historical Association, “The Death of John Bacon.”

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon.”

- The New-Jersey Gazette, January 1783.

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 252.

- All Things Liberty, “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers.”

- Encyclopedia of New Jersey, ed. Maxine Lurie and Marc Mappen, 624.

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon.”

- Monmouth County Historical Association, “The Death of John Bacon.”

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 255.

- David J. Fowler, “Captain John Bacon.”

- All Things Liberty, “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers.”

- Revolutionary New Jersey, “Long Beach Island Massacre.”

- Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 258.

Bibliography

- All Things Liberty. “Captain John Bacon and the Jersey Pine Robbers.” Accessed November 2025.

- Fowler, David J. “Captain John Bacon: The Last of the Jersey Pine Robbers.” Journal of the American Revolution (2021).

- Lurie, Maxine, and Marc Mappen, eds. Encyclopedia of New Jersey. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

- Monmouth County Historical Association. “The Death of John Bacon.” Accessed November 2025.

- Revolutionary New Jersey. “Long Beach Island Massacre.” Accessed November 2025.

- Salter, Edwin. A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, New Jersey. Bayonne, NJ: E. Gardner & Son, 1890.

- The New-Jersey Gazette. October 30, 1782. Archival reprint via Monmouth County Historical Association.

- The New-Jersey Gazette. January 1783. Archival copy via Monmouth County Historical Association.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.