Napoleon’s most enduring and dangerous achievement was not territorial expansion or imperial spectacle, but the quiet success of making his authority feel ordinary.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Power Learned to Disappear into Procedure

The political problem confronting France after the Revolution was not how to overthrow authority, but how to make authority survivable. Years of ideological experimentation, institutional collapse, and legal improvisation had produced exhaustion rather than liberation. Law varied wildly by region, administration lacked coherence, and legitimacy itself seemed permanently unstable. Revolutionary ideals had promised emancipation but delivered unpredictability, leaving citizens wary of both absolutism and popular sovereignty. What people increasingly desired was not another theory of power, but consistency. In this climate, authority that announced itself loudly appeared dangerous, a reminder of the volatility of recent years. Authority that claimed to be merely procedural, technical, and corrective appeared not only acceptable but necessary.

It was within this context that Napoleon Bonaparte recognized a fundamental truth about modern authority. Spectacle fades, monuments erode, and charisma expires with the body that carries it. Systems, however, endure. Napoleon did not abandon personal ambition. He refined it. Rather than anchoring legitimacy in performance or symbolism, he embedded it within structures that presented themselves as neutral, rational, and universally beneficial. Power no longer needed to be admired. It needed to be followed.

This marked a decisive shift in how political authority operated. Under Napoleon, legitimacy moved away from visible dominance and into routine compliance. Administration replaced persuasion. Codification replaced rhetoric. The state no longer asked citizens to believe in it or identify emotionally with it. It asked them to use it. Law became something encountered daily in contracts, marriages, inheritances, property transfers, and civil disputes. Each interaction reinforced the same lesson: order flowed from standardized procedure, not from debate or consent. Through repetition, authority ceased to feel imposed. It felt normal, even helpful. Procedure accomplished what proclamations and ceremonies could not. It trained obedience through habit, embedding power so deeply into daily life that it became difficult to imagine social order without it.

What follows argues that Napoleon’s most enduring achievement was not conquest, empire, or even national reorganization, but the laundering of personal authority through bureaucratic normalcy. By embedding his name and priorities into systems that appeared ideologically thin and administratively rational, he ensured that his influence would outlast his regime. Power did not disappear. It learned how to hide. And in hiding within procedure, it achieved a permanence that open domination rarely secures.

After Revolution: The Political Need for Administrative Stability

The French Revolution dismantled far more than monarchy. It dismantled the inherited legal and administrative coherence that had allowed the state to function across regions, classes, and generations. Revolutionary governments abolished feudal privileges, restructured jurisdictions, and experimented with new constitutional forms, but they did so at tremendous speed and often without durable replacement. Laws multiplied, overlapped, and contradicted one another, shifting with each political turn. Courts applied different standards from one department to the next. What emerged was not clarity but fragmentation, a landscape in which authority existed everywhere and nowhere at once, visible but unreliable.

This instability produced a profound crisis of confidence. Citizens could no longer rely on precedent, local custom, or even recent statute to predict how the state would act. Property rights were unsettled, family law uncertain, contracts vulnerable, and inheritance contested. Justice appeared arbitrary not because it was tyrannical, but because it was inconsistent. The Revolution had promised equality before the law, yet the absence of a stable legal framework made equality feel theoretical rather than lived. Order itself became suspect, associated either with counterrevolutionary nostalgia or with the coercive excesses of the Terror. The result was political fatigue, a widespread desire for rules that would simply hold.

In this environment, ideology lost its appeal as a governing tool. The language of popular sovereignty and civic virtue had mobilized revolution, but it proved ill-suited to routine administration. Governing required predictability more than inspiration. What people increasingly demanded was not political participation, but reliability. The state needed to become legible again. Authority had to appear regular, impartial, and continuous rather than expressive or moralizing. Stability became the primary political good.

Napoleon recognized that this demand for stability created an opening for a new kind of power. Rather than presenting himself as the embodiment of revolutionary ideals or as their repudiation, he positioned himself as their organizer and consolidator. Administration offered a way to satisfy revolutionary promises without reopening revolutionary conflict. By standardizing procedures, harmonizing laws, and centralizing oversight, Napoleon could claim to complete the Revolution by ending its disorder. Authority would no longer be argued over in assemblies or imposed through emergency measures. It would be normalized through process.

Administrative stability became the foundation upon which legitimacy could be rebuilt. By restoring consistency without restoring monarchy in name, Napoleon offered France something it had not known for a generation: routine. Bureaucracy replaced ideology as the language of governance. In doing so, it made authority feel technical rather than political. The Revolution had taught France how to overthrow power. Napoleon taught it how to live with power again.

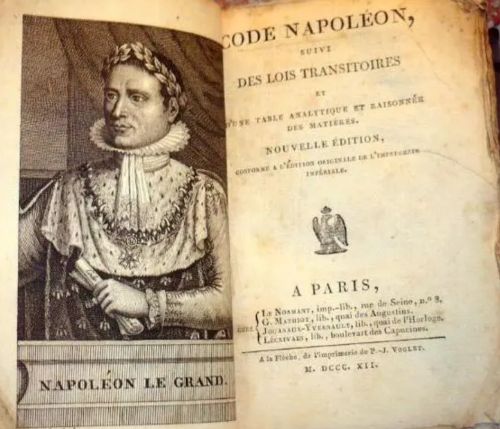

The Napoleonic Code as a Technology of Memory

The Napoleonic Code was conceived not merely as a legal reform but as a solution to the problem of historical instability. France did not lack laws after the Revolution. It suffered from too many of them, layered unevenly across regions and regimes, each carrying the political residue of its moment of origin. Codification promised resolution through simplification. By reducing law to a single, coherent body, Napoleon offered France a past that could be closed and a future that could be standardized.

At its core, the Code transformed law from an expression of authority into a mechanism of repetition. Rather than commanding loyalty through ideology or force, it trained compliance through routine use. Marriage contracts, property transfers, inheritance disputes, and civil obligations all flowed through the same standardized framework. Each encounter reinforced the same logic of order and predictability. The Code became less a visible assertion of power than an unquestioned background condition of social life. Law ceased to feel like an intervention imposed by the state and began to feel like infrastructure, something encountered constantly but rarely interrogated. Authority endured not because it persuaded, but because it repeated.

The naming of the Code mattered profoundly. Though framed as a rational synthesis of Roman law, customary practice, and revolutionary principles, it carried Napoleon’s name from the outset. This was not incidental vanity. It was a deliberate act of inscription. By attaching his name to a system designed to appear neutral, technical, and timeless, Napoleon embedded personal authority within everyday life. Citizens did not need to admire Napoleon to live under his legacy. They needed only to marry, inherit, contract, or litigate. Each legal interaction quietly reaffirmed the association between order and the emperor’s name, even as that association faded into normalcy. Personal authority was preserved precisely by being disguised.

The Code also narrowed the space for alternative legal memory. Customary law, regional variation, and judicial interpretation were subordinated to centralized text. What had once been negotiated locally, adapted to circumstance, or shaped by communal tradition was now fixed, portable, and repeatable. This did not eliminate discretion entirely, but it constrained it within a framework that privileged uniformity over debate and continuity over evolution. Legal memory became national rather than communal, and national memory bore a single authorial imprint. The past was not erased, but it was reorganized around a new center of gravity.

Napoleon achieved something monuments and titles could not. He normalized his authority by embedding it within the mundane operations of society. The Code did not ask to be revered. It asked to be used. In doing so, it converted personal rule into administrative habit, ensuring that Napoleon’s imprint would survive political upheaval precisely because it no longer appeared personal at all.

Neutral Law, Personal Authority

The promise of the Napoleonic Code rested on its claim to neutrality. It presented itself as rational, universal, and stripped of ideological excess, a legal framework grounded in reason rather than political passion. In the wake of revolutionary volatility, this posture carried enormous appeal. Neutral law suggested an end to faction, an escape from moral absolutism, and a return to governable normality. By framing law as technical rather than political, the Code positioned itself above dispute, as something to be applied rather than argued. This posture reassured a population exhausted by constant constitutional reinvention, offering stability without asking for renewed belief. Neutrality became not just a legal claim but a psychological balm.

Yet neutrality functioned less as a description than as a strategy. The Code did not emerge from a vacuum of reason. It reflected deliberate choices about authority, hierarchy, property, gender, and family that aligned closely with Napoleon’s vision of social order. Equality before the law coexisted with sharp constraints on women’s rights, reinforced paternal authority, and protected property in ways that stabilized elite control. These were not neutral outcomes. They were political settlements presented in the language of inevitability.

This rhetorical framing had powerful effects. By disguising authority as procedure, the Code narrowed the space for contestation. Legal outcomes appeared to flow from rules rather than rulers, from text rather than power. Citizens encountering the law were not asked to assent to a political order or affirm a sovereign’s legitimacy. They were asked to comply with a system that claimed no authorial intention at all. The effect was subtle but profound. Disagreement could be dismissed not as political dissent but as misunderstanding or misapplication. Authority became impersonal in appearance even as it remained deeply structured by personal priorities.

This impersonality protected legacy. A ruler whose authority is visibly personal invites resistance when that person falls. A system that appears neutral survives precisely because it does not announce ownership. Napoleon’s genius lay in recognizing that durability required withdrawal from visibility. By embedding control within ostensibly objective frameworks, he ensured that obedience would continue even when admiration waned. Law could outlast the emperor because it did not seem to belong to him.

The tension between neutrality and authorship became most visible in moments of enforcement. Judges applied standardized codes, administrators followed uniform procedures, and officials justified decisions by reference to text rather than command. Appeals were resolved through citation rather than deliberation. Yet the framework within which these decisions occurred had been carefully engineered to reflect a centralized, hierarchical vision of order. Neutrality did not eliminate power. It reorganized it, channeling authority through routines that appeared automatic and unchallengeable. The more mechanical the process appeared, the less political it seemed.

The Napoleonic Code perfected a modern form of domination. Power did not demand loyalty or spectacle. It demanded routine. By presenting law as a neutral instrument of social coordination, Napoleon transformed personal authority into a background condition of daily life. What could no longer be seen as personal could no longer be easily resisted. Neutral law became the most efficient carrier of permanent rule, precisely because it trained subjects to experience authority not as command, but as common sense.

Naming Infrastructure: Roads, Schools, Titles, and Honors

Napoleon understood that law alone could not secure permanence. Legal systems endure most effectively when reinforced by physical and social infrastructure that makes authority tangible. Roads, schools, administrative divisions, titles, and honors formed a second layer of inscription, translating abstract governance into lived experience. These systems did not merely support the state. They taught citizens how to encounter it. Each interaction reinforced the sense that order was centralized, rational, and continuous, regardless of who occupied the throne.

Infrastructure in this sense functioned as pedagogy. Roads standardized space, making the state navigable and measurable in ways earlier regimes had never achieved. Administrative geography replaced historical regions with departments designed for efficiency rather than tradition, erasing local memory in favor of centralized legibility. Schools standardized knowledge, language, and civic identity, producing citizens trained to think within the categories of the state. None of this required constant ideological reinforcement. The system taught itself through repetition. Movement, education, taxation, and administration all followed the same logic of uniformity, quietly reinforcing the perception that the state operated according to necessity rather than political choice.

Titles and honors played a complementary role by binding personal ambition to institutional loyalty. The Legion of Honor exemplified this strategy. It rewarded service to the state while bypassing hereditary privilege, creating a new elite whose status derived directly from administrative recognition rather than lineage. Recognition became portable, visible, and contingent on continued alignment with central authority. Prestige no longer flowed primarily from ancestry or locality, but from demonstrated usefulness to the regime. Ambition was redirected away from resistance and toward participation, making loyalty feel aspirational rather than coerced.

These systems bore Napoleon’s imprint without relying on overt glorification. Roads were not monuments, and schools were not shrines. Titles were framed as meritocratic rather than personal gifts. Yet the coherence of the system depended on a single organizing will. By attaching authority to infrastructure rather than spectacle, Napoleon ensured that his presence would be felt even where his image was absent. Power became ambient, encountered not as reverence or awe but as functionality.

This strategy also insulated legacy from political volatility. Infrastructure, once established, is difficult to dismantle without disruption. Roads continue to be traveled, schools continue to teach, and administrative divisions continue to structure governance long after regimes fall. By embedding authority into these systems, Napoleon ensured that subsequent governments would inherit his framework even as they repudiated his rule. Restoration governments could change symbols and rhetoric, but dismantling the underlying administrative order would have meant chaos. The system could be criticized. It could not easily be replaced.

Napoleon converted personal authority into civic routine. Roads, schools, titles, and honors trained citizens to experience governance as practical necessity rather than political imposition. The result was a form of dominance that survived not through memory or myth, but through daily use. Authority endured because it no longer announced itself. It simply worked.

Survival after Defeat: How the Brand Outlived the Emperor

Napoleon’s political collapse was swift and spectacular. Military defeat, exile, and the restoration of monarchy appeared, at first glance, to mark a decisive rupture with the Napoleonic order. The dramatic symbolism of abdication and banishment suggested finality, a return to pre-revolutionary norms, and the erasure of imperial influence. Yet beneath the surface of regime change, much of the system he had constructed remained intact. The return of the Bourbons did not bring wholesale administrative reversal. Law courts continued to operate under the Code, officials continued to administer standardized departments, and citizens continued to interact with the state through procedures shaped by the empire. Defeat removed the emperor. It did not remove his systems, nor did it erase the habits of governance those systems had created.

This endurance was not accidental. The Napoleonic project had been engineered precisely to survive political fluctuation by presenting itself as necessary rather than ideological. The Code was framed as rational law, not imperial doctrine. Administrative divisions were justified by efficiency and clarity, not loyalty or symbolism. Schools trained competence and discipline rather than overt devotion. Because these systems appeared neutral and practical, their retention could be justified even by regimes that rejected Napoleon personally. To dismantle them would have meant admitting that order itself was partisan and fragile. Continuity became the safer political choice, allowing restoration governments to claim stability while quietly inheriting the machinery of empire.

This continuity reshaped memory. Napoleon could be condemned as a tyrant, an adventurer, or a usurper, while his administrative achievements were praised as enlightened reform. The separation of person from system allowed his legacy to be selectively preserved. Law, infrastructure, and bureaucracy were treated as accomplishments of modern governance rather than as expressions of personal power. The emperor faded into history, but the logic he imposed remained active in everyday life.

Napoleon achieved a form of posthumous authority unmatched by many more openly celebrated rulers. His name survived not through monuments or ritual, but through normalized procedure. The brand outlived the body because it had learned to masquerade as common sense. Power endured precisely because it no longer looked like power at all.

From Rule to Routine: The Disguised Permanence of Power

The most consequential transformation effected by the Napoleonic system was the conversion of rule into routine. Authority no longer depended on constant assertion, personal presence, or ideological reaffirmation. It became embedded in processes that repeated themselves regardless of who occupied the apex of power. Citizens encountered governance not as an act of domination, but as a series of standardized interactions that structured daily life. Power endured not because it demanded recognition, but because it organized necessity.

This shift altered the psychology of obedience. When authority is experienced as procedure, resistance becomes cognitively difficult. One can oppose a ruler, challenge a decree, or reject an ideology, but routine offers no obvious target. Forms must be filed. Contracts must be recognized. Courts must be used. The state becomes unavoidable not through coercion, but through integration. Participation in administrative processes becomes a condition of social existence. Obedience is learned not through fear or loyalty, but through familiarity. Compliance feels less like submission and more like common sense.

Routine also diffused responsibility in ways that protected the system from moral reckoning. Decisions appeared to emerge from process rather than choice. Outcomes could be attributed to law, precedent, or administrative requirement rather than human judgment. Officials became interpreters rather than authors of authority. This diffusion did not eliminate power. It shielded it. Authority operated behind layers of procedure that transformed political decisions into technical outcomes, insulating them from challenge while preserving their effects. Responsibility was everywhere and nowhere, embedded in systems that appeared to act on their own.

The durability of this arrangement lay in its apparent modesty. Unlike spectacle-driven regimes, the Napoleonic system did not require constant performance to sustain legitimacy. It required maintenance. Bureaucracy proved far more resilient than charisma because it did not rely on belief. It relied on use. As long as people continued to participate in its routines, the system reproduced itself. Power survived by becoming boring.

Napoleon achieved a form of permanence that exceeded personal memory. His authority did not need to be celebrated, defended, or even remembered. It needed only to be practiced. By embedding power into routine, Napoleon ensured that his legacy would persist quietly, shaping lives without announcing itself. Rule ended. Routine remained.

Conclusion: When Legacy Stops Looking Like Legacy

Napoleon’s most enduring achievement was not territorial expansion or imperial spectacle, but the quiet success of making his authority feel ordinary. By embedding power in law, infrastructure, and administrative routine, he transformed personal rule into something that appeared impersonal, rational, and inevitable. Unlike regimes that rely on memory, myth, or constant reaffirmation, the Napoleonic system survived by asking very little of its subjects. It required no loyalty beyond participation, no belief beyond compliance. In doing so, it escaped the usual fate of personal rule.

This invisibility is precisely what made the legacy durable. When power announces itself loudly, it invites confrontation and eventual rejection. When it presents itself as neutral procedure, it becomes difficult to identify as power at all. The Napoleonic Code, standardized administration, and institutional infrastructure did not look like monuments to an emperor. They looked like common sense. By the time Napoleon himself was gone, his imprint had already been absorbed into the grammar of governance, reproduced daily without reference to its origin.

The danger of this form of legacy lies in its deniability. Because authority appears to reside in systems rather than persons, it becomes harder to question whose interests those systems serve. Decisions are framed as technical necessities rather than political choices. Responsibility dissolves into process. What once required justification now requires only administration. Power persists not because it persuades, but because it is difficult to imagine alternatives.

Napoleon perfected a modern template for permanence. Legacy no longer needed to be celebrated or defended. It needed only to be normalized. When power stops looking like legacy, it becomes far more difficult to dislodge. The Napoleonic system reminds us that the most durable authority is not the kind that demands remembrance, but the kind that teaches us to forget that it was ever imposed.

Bibliography

- Amos, Maurice. “The Code Napoléon and the Modern World.” Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law 10:4 (1928), 222-236.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

- Bell, David A. The Cult of the Nation in France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- —-. The First Total War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

- Broers, Michael. Europe Under Napoleon. London: Arnold, 1996.

- —-. Napoleon: Soldier of Destiny. London: Faber & Faber, 2019.

- Englund, Steven. “Monstre Sacré: The Question of Cultural Imperialism and the Napoleonic Empire.” The Historical Journal 51:1 (2008), 215-250.

- Halpérin, Jean-Louis. The French Civil Code. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Hazareesingh, Sudhir. “Napoleonic Memory in Nineteenth-Century France: The Making of a Liberal Legend.” MLN 120:4 (2005), 747-773.

- Issawi, Charles. “The Costs of the French Revolution.” The American Scholar 58:3 (1989), 371-381.

- Lobingier, Charles Sumner. “Napoleon and His Code.” Harvard Law Review 32:2 (1918), 114-134.

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

- Napoleon Bonaparte. Code Civil des Français (1804).

- Palmer, R. R. The Age of the Democratic Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de. The Old Regime and the Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998 ed.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.09.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.