The environmental consequences of the Texas oil boom reveal how technological achievement and ecological degradation advanced side by side.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the discovery of vast oil reserves in Texas transformed the state’s economy and helped reshape the industrial United States. With the 1901 gusher at Spindletop near Beaumont heralding a new era of petroleum production, Texas emerged as a global energy center and the petroleum industry expanded rapidly.1 This boom in extraction and refining brought enormous wealth, created new kinds of towns and labor patterns, and propelled Texas into the forefront of U.S. oil and gas production.2 Yet beneath the surface of economic triumph lay an often-overlooked dimension: the environmental consequences of intensive oil production, including soil and groundwater contamination, air-pollution burdens, ecosystem disruption, and the long-term legacy of abandoned wells and waste-disposal infrastructure.

What follows argues that while the Texas oil boom delivered substantial economic gains for the state, it also generated serious and long-term environmental effects. These effects stemmed from the intensity and speed of extraction, limited early regulation, and infrastructure designed for growth rather than environmental protection. In turn, those consequences have shaped regulatory responses, community vulnerabilities, and ongoing remediation challenges. To demonstrate this argument, the essay proceeds as follows: it first traces the background of the Texas oil boom and extraction practices, then examines the primary environmental consequences, reviews regulatory and community responses, and concludes with an assessment of the long-term legacies and broader significance of the boom’s environmental footprint.

Background: The Texas Oil Boom and Extraction Dynamics

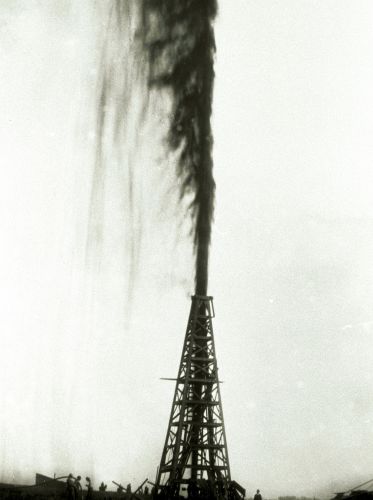

The Texas oil boom began in 1901 when the Lucas Gusher erupted at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, spewing oil more than 100 feet into the air and producing over 100,000 barrels a day.3 The discovery instantly transformed Texas from an agricultural frontier into an industrial power. Within months, drilling companies, speculators, and laborers flooded into the region, creating a chaotic but lucrative frontier economy.4 The Gulf Coast, once dominated by cotton and cattle, became a sprawling industrial landscape of rigs, refineries, and pipelines stretching toward Houston and Port Arthur. The rush to drill brought a new type of town (transient, speculative, and often unregulated) where waste pits overflowed, gas flares burned day and night, and oil seeped into the soil long before environmental oversight existed.

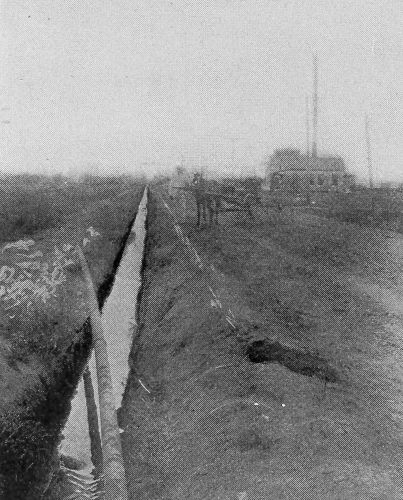

By the 1920s and 1930s, new discoveries in East Texas and the Permian Basin extended the boom’s reach across the state.5 The East Texas field, discovered in 1930, became one of the largest in the world, producing billions of barrels and drawing thousands of workers seeking quick fortune.6 Such explosive growth came with massive surface disruption: forests were cleared, creeks diverted, and the land riddled with derricks spaced only a few yards apart. Texas’s output soon rivaled that of entire nations, and the infrastructure needed to sustain it (refineries, pipelines, tank farms) expanded with little consideration for ecological consequences. The early industry treated waste oil and brine as inevitable by-products to be dumped or burned, leaving behind scars that would persist for generations.

At first, no single authority existed to regulate extraction or manage its externalities. The Texas Legislature created the Railroad Commission in the nineteenth century to oversee transportation but later granted it jurisdiction over oil and gas production, making it one of the most powerful state agencies in the country.7 Early conservation laws focused not on environmental protection but on stabilizing production and preventing price collapse.8 Over time, however, the scale of damage (abandoned wells, groundwater contamination, and oil-field fires) forced limited efforts toward regulation. These first measures marked the beginning of Texas’s uneasy balance between economic expansion and environmental stewardship, a tension that would define the state’s industrial identity for the next century.

Primary Environmental Consequences

The environmental cost of the Texas oil boom became evident almost as soon as the first gushers erupted. In the early decades of production, drilling waste and crude oil were routinely discharged into nearby creeks and wetlands, killing vegetation and wildlife across the Gulf Coast.9 The primitive technology of the time offered little control: unlined pits overflowed during rains, and earthen dams leaked brine and hydrocarbons into the soil.10 Fields such as Spindletop, Humble, and Goose Creek soon transformed from coastal prairie to industrial wasteland, their once-fertile soil blackened by oil seeps.11 Without legal mechanisms to compel cleanup, companies simply abandoned exhausted wells, leaving behind thousands of open casings that leaked contaminants into groundwater for decades.

Air pollution also accompanied the boom, especially as refineries multiplied along the coast from Beaumont to Houston. By the 1920s, constant gas flaring and incomplete combustion produced thick clouds of smoke that blanketed the region.12 Communities near refineries in Port Arthur and Baytown reported persistent soot deposits and respiratory irritation long before scientific studies documented the risks.13 Later, during the mid-century expansion of petrochemical complexes, airborne emissions of sulfur dioxide, benzene, and volatile organic compounds created some of the highest concentrations of industrial pollutants in the United States.14 The environmental gains achieved by technological innovation, such as high-pressure drilling and pipeline transport, were offset by the equally dramatic rise in refinery emissions and chemical waste.

Equally destructive were the effects on surface and groundwater. Produced water, the salty by-product of drilling, was routinely dumped into streams and pastures.15 Over time, salinity levels in surrounding aquifers rose, degrading irrigation water and contributing to vegetation die-off. In the absence of regulatory storage or reinjection rules, companies often used unlined earthen ponds to hold brine and sludge, which leached into shallow aquifers across East Texas.16 Even as late as the 1970s, field surveys found hundreds of leaking pits and unplugged wells contaminating groundwater in the Permian Basin.17 The cumulative result was a patchwork of invisible contamination zones that persisted long after the economic boom subsided.

Landscapes themselves underwent dramatic alteration. The clearing of forest for drilling sites, roads, and pipelines destroyed large areas of coastal prairie and pine forest.18 Coastal marshes, once natural filters for the Gulf ecosystem, were dredged to create shipping channels for crude exports.19 Industrial runoff from these facilities entered Galveston Bay and the Houston Ship Channel, turning once-productive fisheries into polluted zones by mid-century.20 The visual legacy of extraction (derricks, pits, and flare stacks) signaled a transformation in the human relationship to land: from stewardship to exploitation. The ethos of the oil frontier left little room for ecological preservation.

The persistence of environmental hazards long after well closure remains one of the boom’s most enduring legacies. Tens of thousands of “orphan wells,” left unplugged or inadequately sealed, continue to emit methane and contaminate aquifers across the state.21 Many of these date to early wildcat operations that predated formal permitting.22 Their presence underscores a broader pattern of deferred responsibility that continues to challenge Texas regulators today. Cleanup efforts by the Railroad Commission have plugged thousands, yet funding shortfalls leave countless others untouched.23 The environmental consequences of the Texas oil boom thus extend beyond history; they constitute a living inheritance of contamination and risk embedded in the state’s very landscape.

Regulatory, Institutional, and Community Responses

Efforts to regulate Texas’s oil industry emerged slowly and often prioritized economic stability over environmental protection. The Texas Legislature had created the Railroad Commission in 1891 to oversee transportation, but as oil production skyrocketed, the agency’s authority expanded to include conservation and well-spacing rules.24 Early conservation laws, such as those passed in the 1910s and 1920s, sought primarily to prevent overproduction and protect market prices, not to mitigate environmental harm.25 The Commission imposed “prorationing” to manage output and stabilize the industry after the East Texas field flooded markets in 1931, yet it largely ignored the growing waste of drilling fluids and produced water.26 The ecological effects of extraction were viewed as secondary costs of progress, consistent with the state’s pro-development ethos and political alignment with oil interests.

By the mid-twentieth century, limited regulatory efforts began to address the visible damage left by early drilling practices. The Railroad Commission implemented well-plugging standards to reduce groundwater contamination, though enforcement remained inconsistent.27 Legislative measures in the 1960s and 1970s authorized state funds for plugging abandoned wells, but the number of new orphaned sites outpaced cleanup budgets.28 The Texas Water Quality Act of 1967 and the creation of the Texas Water Commission signaled growing recognition of environmental degradation, especially as industrial runoff reached coastal and inland waters.29 Yet regulatory capacity was hampered by limited staffing, political influence from the oil industry, and the persistent prioritization of economic output over ecological recovery.

Community response to these issues varied across the state, often reflecting local exposure and economic dependence on oil. In refinery towns such as Port Arthur and Baytown, residents experienced persistent air-quality violations and elevated rates of respiratory illness.30 Grassroots advocacy in these areas, particularly from Black and Latino communities, helped shape early environmental justice movements in Texas.31 Scholars and journalists have since documented how proximity to refineries and waste-injection wells correlated with racial and economic vulnerability, creating long-term disparities in exposure.32 While industrial leaders often emphasized the jobs and revenue the oil sector provided, many affected communities came to view environmental degradation as a form of economic coercion that forced them to choose between livelihood and health.

In recent decades, state and federal initiatives have sought to address the lingering legacies of the oil boom through cleanup programs and environmental restoration. The Texas Railroad Commission’s Orphan Well Program has plugged thousands of abandoned wells, supported partly by federal funding under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021.33 However, thousands more remain unaddressed, highlighting the challenge of reconciling a century of unregulated extraction with modern environmental standards.34 The continuing struggle between regulatory ambition and economic dependency reveals that the Texas oil boom was not only a story of industrial triumph but also a prolonged test of environmental governance, one whose consequences still shape the state’s political and ecological landscape.

Long-Term Legacies and Significance

The environmental legacy of the Texas oil boom endures in the physical and social landscape of the state. Vast networks of aging wells, pipelines, and refineries continue to define Texas’s geography, while the remnants of early extraction (polluted soils, brine ponds, and degraded wetlands) remain visible reminders of an industry that grew faster than its capacity to manage waste.35 Methane emissions from unplugged wells, documented by the Environmental Defense Fund and state monitoring programs, contribute to greenhouse gas levels at a rate comparable to modern production sites.36 In some counties, groundwater near former oil fields still contains elevated chloride and hydrocarbon concentrations, reflecting contamination that began more than a century ago.37 This enduring pollution has complicated land reuse, limiting agricultural recovery and driving property devaluation across once-productive regions.

These environmental consequences have also shaped Texas’s political and regulatory identity. The state’s long dependence on oil revenue has often constrained environmental policymaking, creating a legacy of institutional caution toward stricter regulation.38 The Railroad Commission, though tasked with environmental oversight, remains deeply tied to the industry it governs.39 Meanwhile, modern environmental agencies have inherited the complex task of reconciling industrial growth with ecological restoration. The struggle between economic power and environmental responsibility, first visible at Spindletop, has persisted across decades of deregulation, litigation, and periodic reform. This dynamic reflects a broader national pattern in which states rich in fossil-fuel resources face the hardest path toward environmental transition.

The broader significance of the Texas oil boom lies in its illustration of how extractive economies produce enduring ecological and social consequences. The transformation of Texas from a frontier landscape to an industrial powerhouse offers a case study in both progress and peril. The environmental damage wrought by a century of oil extraction underscores the costs of unchecked industrial growth and the inadequacy of reactive policy.40 Understanding this history is crucial not only for Texas but for all regions confronting the aftermath of resource dependence. The lesson of the Texas oil boom is that environmental recovery, like the resource itself, is finite and fragile, shaped by the choices of those who profit and those who must live with the residue.

Conclusion

The environmental consequences of the Texas oil boom reveal how technological achievement and ecological degradation advanced side by side. From the first gusher at Spindletop to the sprawling refinery complexes that now line the Gulf Coast, the industry’s growth outpaced both scientific understanding and legal accountability. The extraction frenzy that fueled national prosperity also eroded the land and water upon which local communities depended.41 What began as a triumph of ingenuity became a case study in environmental neglect, leaving a network of abandoned wells, contaminated aquifers, and polluted air that still burdens the state. Even as modern technologies improve efficiency, the residues of a century of production remain embedded in the soil, groundwater, and coastlines of Texas.

In retrospect, the Texas oil boom stands as a pivotal moment in American environmental history, an era that transformed not only economies but ecosystems. Its legacy underscores the necessity of foresight in balancing industrial ambition with ecological responsibility.42 The story of Texas illustrates that progress measured solely by output conceals costs that unfold across generations. The state’s ongoing struggle to manage orphan wells, restore damaged landscapes, and regulate emissions reflects a broader moral reckoning with the true price of energy.43 The environmental lessons of the boom are not confined to history; they remain urgent in an age still defined by fossil fuels. To understand the Texas oil boom is to confront the enduring tension between prosperity and preservation, a tension that continues to shape both Texas and the world beyond it.

Appendix

Footnotes

- “Oil and Gas Industry,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History,” Texas Almanac.

- “Spindletop,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, accessed November 2025.

- Texas State Library and Archives Commission, “Extra! Extra! Read All About the Spindletop Oil Discovery,” accessed November 2025, https://www.tsl.texas.gov/lobbyexhibits/extraextra/spindletop.

- “Oil and Gas Industry,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “East Texas Oil Field,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Railroad Commission of Texas,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History,” Texas Almanac.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History,” Texas Almanac.

- “Oil and Gas Industry,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Goose Creek Oil Field,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Industrial Air Pollution in Texas,” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality historical archives, accessed November 2025.

- “Port Arthur Refinery History,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Texas Industrial Emissions Inventory Report, 1977.

- “Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking, and Environmental Justice,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 3 (2016).

- “Oil-Field Waste and Groundwater Contamination,” Texas Groundwater Protection Committee, 2001.

- “Permian Basin Water Quality Report,” Texas Water Development Board, 1978.

- “Forests and Oil Development,” Texas Almanac.

- “Galveston Bay Estuary Program Report,” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 1995.

- “Houston Ship Channel Pollution History,” Environmental History 19, no. 4 (2014).

- “Texas Has Thousands of Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells,” Texas Tribune, May 8, 2025.

- “Orphan Well Program,” Railroad Commission of Texas, accessed November 2025.

- “Abandoned Wells Report,” Texas General Land Office, 2023.

- “Railroad Commission of Texas,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Oil and Gas Conservation Laws,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “East Texas Oil Field,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Plugging Rules for Abandoned Wells,” Railroad Commission of Texas, accessed November 2025.

- “Abandoned Wells Report,” Texas General Land Office, 2023.

- “Texas Water Quality Act of 1967,” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality historical summary.

- “Port Arthur Refinery History,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- Robert D. Bullard, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality (Boulder: Westview Press, 1990).

- “Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking, and Environmental Justice,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 3 (2016).

- “Orphan Well Program Update,” Railroad Commission of Texas, 2024.

- “Texas Has Thousands of Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells,” Texas Tribune, May 8, 2025.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History,” Texas Almanac.

- Environmental Defense Fund, “Mapping Orphan Wells in Texas,” 2022.

- Texas Water Development Board, Groundwater Quality Report, 2023.

- “Railroad Commission of Texas,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “State Oil and Gas Regulation,” U.S. Government Accountability Office Report GAO-22-104586, 2022.

- “Texas Environmental Policy History,” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 2024.

- “Oil and Gas Industry,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “Texas Environmental Policy History,” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 2024.

- “Texas Has Thousands of Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells,” Texas Tribune, May 8, 2025.

Bibliography

- Bullard, Robert D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Boulder: Westview Press, 1990.

- Environmental Defense Fund. “Mapping Orphan Wells in Texas.” 2022.

- “East Texas Oil Field.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History.” Texas Almanac.

- “Galveston Bay Estuary Program Report.” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 1995.

- “Goose Creek Oil Field.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- “Houston Ship Channel Pollution History.” Environmental History 19, no. 4 (2014).

- “Industrial Air Pollution in Texas.” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Historical Archives. Accessed November 2025.

- “Oil and Gas Conservation Laws.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- “Oil and Gas Industry.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- “Oil and Texas: A Cultural History.” Texas Almanac.

- “Oil-Field Waste and Groundwater Contamination.” Texas Groundwater Protection Committee, 2001.

- “Orphan Well Program.” Railroad Commission of Texas. Accessed November 2025.

- “Orphan Well Program Update.” Railroad Commission of Texas, 2024.

- “Permian Basin Water Quality Report.” Texas Water Development Board, 1978.

- “Plugging Rules for Abandoned Wells.” Railroad Commission of Texas. Accessed November 2025.

- “Port Arthur Refinery History.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- Railroad Commission of Texas. “Abandoned Wells Report.” Texas General Land Office, 2023.

- ———. “Railroad Commission of Texas.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- “Spindletop.” Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed November 2025.

- State Library and Archives Commission, Texas. “Extra! Extra! Read All About the Spindletop Oil Discovery.” Accessed November 2025. https://www.tsl.texas.gov/lobbyexhibits/extraextra/spindletop.

- “State Oil and Gas Regulation.” U.S. Government Accountability Office Report GAO-22-104586, 2022.

- “Texas Environmental Policy History.” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 2024.

- “Texas Has Thousands of Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells.” Texas Tribune. May 8, 2025.

- “Texas Industrial Emissions Inventory Report.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1977.

- “Texas Water Quality Act of 1967.” Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Historical Summary.

- Texas Water Development Board. Groundwater Quality Report. 2023.

- “Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking, and Environmental Justice.” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 3 (2016).

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.