The appearance of The New Game of Human Life on 14 July 1790 was a significant milestone in the history of British leisure.

By Dr. Christopher Rovee

Professor of Literature

Louisiana State University

Introduction

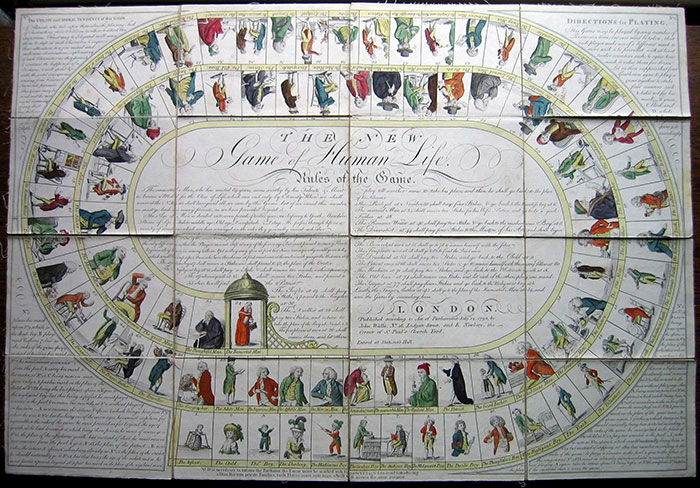

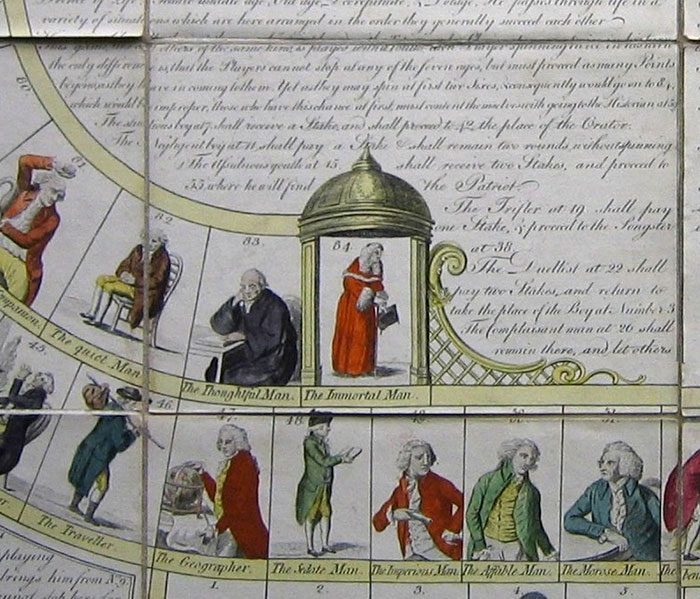

The New Game of Human Life was published by Act of Parliament on 14 July 1790. Famous today in its modern incarnation as Life, the iconic board game that for many decades anchored the American gaming empire of Milton Bradley Corporation, The New Game of Human Life appeared under the shared imprint of John Wallis and Elizabeth Newbery, leading London publishers that would go on to produce many similar games for the lucrative market in domestic amusements. The New Game of Human Life was issued as a hand-colored engraving (Fig. 1), printed on sixteen separate pieces of paper and mounted on linen; this cloth-backed playing-sheet could be folded and nestled into a marbled slipcase roughly the size of an octavo book. A separate decorative label was engraved and illustrated for the slipcase. A statement on “The UTILITY and MORAL TENDENCY of this GAME,” along with some directions for game-play, appear in fancy script in the spandrels of the playing surface; the “Rules of the Game” take up the empty space at the center of the racing-spiral. Each individual square on the course represents one year of a hypothetical life and contains a concise, miniature illustration, sometimes of a recognizable personage, representing various stations that such a life might include. There is “The Poet” at space 41, represented by Alexander Pope; “The Patriot” at space 55, embodied by William Pitt; and “The Glutton” at space 59, who resembles many popular satires on the indulgent Prince of Wales. Victory belonged to the player who arrived at the final panel, space 84, where “The Immortal Man” was pictured as Isaac Newton, who had lived to that same age (Fig. 2). Though advertised in its subtitle as “the Most Agreeable and Rational Recreation Ever Invented for Youth of Both Sexes,” the game is entirely male-centered, charting a masculine path through seven distinct twelve-year “ages.”

Modern Markets for ‘Human Life’

The publication of Human Life on the first anniversary of the French Revolution might have been a coincidence, but it is a particularly rich one given the game’s intimacy with various aspects of modernity that the Revolution helped usher in—from what J. H. Plumb calls “the commercialization” and “sophisticated exploitation of leisure” (286, 273); to the specifically modern sense of contingent and disjunctive historical time as described by Reinhart Koselleck (49-57) and others; to the increasingly complex relationship between an individual’s moral development and the thrills and insecurities that attend a life of social mobility. The game sprang from a marketplace that targeted children but made its appeals “through the refraction of the parental eye” (Plumb 301). In this child-centered market, which contributed to (even as it was enabled by) an upsurge in printed ephemera, education and recreation were profitably joined. At the end of the previous century, John Locke proposed to conceal education in the unimposing form of the dice game by replacing dots with letters. “I have always had a Fancy,” he wrote in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), “that Learning might be made a Play and Recreation to Children” (208). By the mid eighteenth century, book publishers were exploiting in earnest the commercial possibilities of pleasurable learning. “Children had become a trade,” as Plumb puts it, “a field of commercial enterprise for the sharp-eyed entrepreneur” (310). Books and toy-like accessories were sold together from at least the 1740s: John Newbery’s Little Pretty Pocket-Book(1744) could be purchased with a ball or a pincushion, as its title page announced, “for the Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly”; the text cites Locke as an inspiration. “For the first time ever,” Brian Alderson writes, “child-focussed book-making went hand-in-hand with commercial nous, and its success may be measured not simply through the frequency with which works were reprinted or the way they were used as models for new publications, but also through the way they were plundered by unscrupulous rivals” (194).

Yet in an age of “heightened rivalry among children’s publishers” (Avery and Kinnell 58), the London version of The New Game of Human Life heralded a different approach. It was the first of many collaborations between two London firms that, between them, had mastered the diverse aspects of child-oriented salesmanship. John Wallis (1764-1818), whose shop at 16 Ludgate Street sometimes went by the name “Map Warehouse,” was a prominent retailer of cartographic puzzles, books, prints, charts, and music; after the success of Human Life, he went on to become the most prolific of London game publishers (Hannas 30-35). To Wallis’s expertise in the home-amusements market, Elizabeth Newbery (1745/6-1821) added a savvy sense of book-marketing, and possibly financial backing (Hannas 32; Shefrin, “Elizabeth Newbery” 571). A niece by marriage of John Newbery, publishing pioneer and namesake of the Newbery Medal, Elizabeth Newbery assumed the family business at the corner of St. Paul’sChurchyard in 1780. Among bibliographers, she is known for having exploited the tendency of child readers to damage illustrated books (see Bottigheimer 17-18); her frequent print runs—“almost annual,” speculates Newbery bibliographer Sidney Roscoe (vii)—were indistinguishable from earlier runs, thus providing owners with replacement copies while leading to later confusion regarding the date of a specific item’s publication. Because of her reprinting practices, it is hard to know how many different times The New Game of Human Life was typeset in the years between its first appearance and its reissue, more than two decades later, under the Wallis imprint. Nearly all recorded copies of the game’s initial edition are dated 14 July 1790, yet there is no reason to assume, given Newbery’s canny marketing strategies and the wear-and-tear that the game-kits themselves underwent, that at least some of these copies were not produced in a subsequent print run. “It is the exception to the rule,” writes the bibliographer and collector D’Alté Welch, “that two Newbery items are identical if they are undated” (quoted in Roscoe vii).[1]

The vibrant coloring of its illustrated playing-surface no doubt made The New Game of Human Life an appealing commodity and cherished domestic possession (though some enhancement is likely to have been undertaken by the game’s owners, as well). The survival of some uncolored and partly colored engravings indicates that, in keeping with its publishers’ savviness, there may have been a sliding-scale to suit various classes of consumer.[2] The advertised pricing hints as much: in 1790, the printed game-sheet alone sold for five shillings, but pasted on a board it went for six. Meanwhile, a complete boxed set, including totum, counters, and a designer slipcase that resembled the outer-covering of a book and allowed the game to be shelved as if it were one, could be had for six-and-a-half shillings (Wallis and Newbery). In all these details, the publishers of The New Game of Human Life provided a blueprint for innumerable successors even as they exploited the one established by their predecessors—mainly in France, where table-games were a popular eighteenth-century adult pastime.

Origins, Associations, Affinities

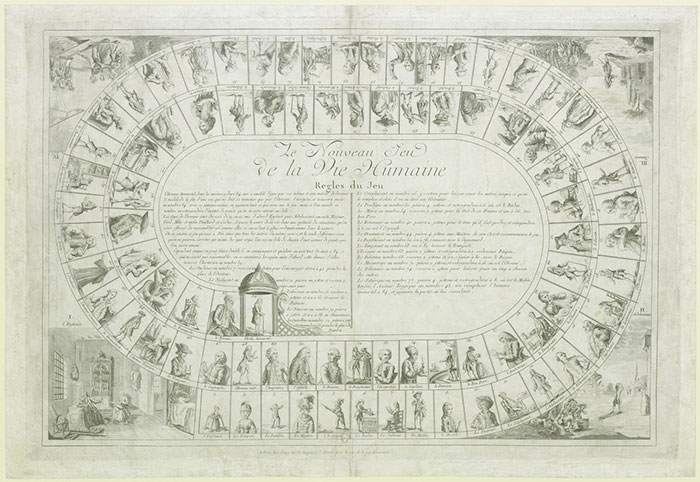

The New Game of Human Life took its practical origins from the continent, where variants of the spiral race game known as “gioco dell’oca” or “jeu de l’oie” (“Game of the Goose”) had been played since at least the mid sixteenth century.[3] In the late 1770s, the Parisian publisher Jean-Baptiste Crépy obtained a license to produce game-boards and promptly issued Le Nouveau Jeu de La Vie Humaine (Fig. 3), in which victory was embodied by the illustrated figure of Voltaire, who occupied the game’s culminating space.[4] (“Quel triste jeu de hasard que le jeu de la vie humaine,” Voltaire had reflected in the aftermath of the 1755

Lisbon earthquake [511]: “What a sad game of chance is the game of human life.”)

Wallis and Newbery drew directly on the French version, reproducing several of its features but gearing these toward their English target audience. The basic structure of “the seven ages of man,” each consisting of twelve years, remained intact, as did many of the game’s moralized rewards and punishments. In the French and English versions alike, a player landing on space 34, “The Married Man” (le Marié), would “receive two Stakes for his Wife’s portion” and skip ahead to the “Good Father” (le Bon Père) at space 56; but to land on space 63, “The Drunkard” (l’Yvrogne), meant paying two to the pool and moving back all the way to space 2, “The Child” (le Poupon). Curiously, while success was keyed to conventional middle-class values, it also meant a shorter life. As Jill Lepore puts it, “Whoever dies first wins” (xix). “The Married Man” skips quickly past middle age, while Drunkards, Duellists, and Romance Writers, though they are not the game’s “winners,” get to inhabit, for better or worse, perpetual childhoods. Here is one of the strange and unexpected ways that Human Life (like modern life) could toy with the perceived movement of time.

Wallis and Newbery did make a couple of significant modifications to their French model. First, the illustrations were adapted to suit English tastes and understandings: Newton, for example, replaced Voltaire as “The Immortal Man” of space 84. A second change was more symbolic, and involved the ideological concerns that shaped the middle-class market for domestic amusements. Whereas Le Nouveau Jeu de La Vie Humaine was played with two dice, The New Game of Human Life instead used a teetotum, a kind of spinning top “commonly made of ivory or bone” (Shefrin, “Make It a Pleasure” 255). This was (as printed on the bottom of the playing-sheet) “to avoid introducing a Dice Box into private Families.” The association of dice with gambling was an uneasy fit with a game of moral instruction; indeed Maria Edgeworth, in Practical Education, warned against “games of chance” precisely because of their tendency “to give a taste for gambling,” a vice that “has been the ruin of so many” (1: 44). Thus, most of the successors to Human Life in the next half-century—and even games that did not have an explicitly moral purpose—similarly avoided dice. “You could gamble in essentials, or in soul,” as the early twentieth-century collector and book-historian Harvey Darton put it, “but be saved by the look of the external symbol or machine” (125n).

As Darton implies, The New Game of Human Life was nothing if not a game of chance. Moral good may have been studiously linked with “success” in the game-play, yet it nevertheless remained a gamble, in a way that may have suggested some of the erratic and inequitable aspects of social mobility. The desire to “tame” the vagaries of chance (Hacking) perhaps made the game’s establishment as an edifying pursuit all the more imperative. This is particularly evident in its explicit appeal to interactivity. Under the heading “Utility and Moral Tendency of this Game,” parents are urged to “take upon themselves the pleasing task of instructing their children” during game-play: they should ask that children “stop at each character” and should make “a few moral and judicious observations, explanatory of each character as they proceed and contrast the happiness of a virtuous and well spent life with the fatal consequences arising from vicious and immoral pursuits.” If this advice is followed, the instructions assert, The New Game of Human Life “may be rendered the most useful and amusing of any [game] that has hitherto been offered to the public.” The injunction to pause the momentum of the game in order to consider the meaning of a “well spent life” could represent a defensive response to the sheer fun of game-play; or perhaps it is just that there is fun to be had in role-playing “A Drunkard,” just for a moment, so as to contemplate the consequences. Pleasure and didacticism need not be a zero-sum game, but there is a friction between them that speaks to the status of The New Game of Human Life, and other morally instructive amusements, as contradictory sites of “instructive gambling” (Darton 150).

Such contradiction is embedded in the concept of le doux commerce, that optimistic enlightenment belief in sociability and private virtue as inextricable from economic success (Hirschman). To “win” at Human Life requires landing, fortuitously, in “virtuous” circumstances, such as “The Benevolent Man” at 52, or “The Patient Man” at 68. Drawing upon a sociable ideal of “commercial humanism” (Pocock 50) that guards against the cynical view that material comfort is best assured through the exercise of selfish passions, the game—like Adam Smith’s economic and moral theories (if less subtly)—holds in delicate balance the values of selflessness and self-interest. Yet this ever-present question of how one “wins” at life holds within it the seeds of some darker possibilities. For in a safe simulation of the real thing, Human Life showed, at the very least, how in a class-mobile society life could sometimes unfold with the contingency and unpredictability of a spin of the totum (if not a roll of the dice). According to Adam Ferguson, the Scottish moral philosopher, this element of chance could be bracing and enjoyable: “The great inventor of the game of human life, knew well how to accommodate the players,” Ferguson wrote; “The chances are matter of complaint; but if these were removed, the game itself would no longer amuse the parties” (71). (Of course, a poor stroke of chance could just as easily cease to “amuse the parties.”) From this less sunny perspective, The New Game of Human Life can be seen as preparing children to lose—a crucially negative capability in a competitive world. Unlike the eighteenth-century sentimental novel, which drew readers into attachment with a particular individual and prioritized the happiness of that character over that of minor ones, amusements like The New Game of Human Life laid bare the essential rivalry of life under capitalism by exposing rivalry in its own narrative, with multiple players vying for a happiness that, in the end, only one would achieve.

The stripped-down structure of narrative in The New Game of Human Life calls attention to the game’s literariness, as well as to certain affinities between such games and the relatively contemporaneous literary genre of the novel—in particular the Bildungsroman, a story of individual development that would soon comprise the novel’s paradigmatic form. To be sure, in keeping with the disruption of linear sequencing that Koselleck associates with a modern world of “contingent eruptions” (Kelley 626), the race-game’s trajectory is more hypertextual than linear: varieties of deviation and non-sequentiality are inscribed into the game-play, giving the “life” it represents an odd and unpredictable rhythm that speeds and slows, progresses and occasionally regresses. Though it lays out for English children a rather harsh course of development, from “Manhood” at age thirteen through “Decrepitude” at age sixty-one, the actual “story” told by the game comes with an endless supply of narrative patterns (all of which nevertheless conclude—for somebody—in the same winning move). There is, of course, a difference between the simulated stories one inhabits as a player of such a game, and the intimate relationship a reader takes up with a book’s characters, and game theorists perennially dispute the applicability of narratology to such amusements.[5] But no doubt there is some relationship to be discerned between the proliferation of race-games around the turn of the nineteenth century and parallel phenomena, such as the rise of the novel, the emergence of romantic spiritual autobiography, and the spread of middle-class portraiture—all of which demonstrate a deepening concern with the individual’s development in an age defined by “a discordant mix of divergent rhythms, variable speeds, and uneven durations” (Comay 4).

Games in Archives

The recent renaissance in game studies has led to a widespread recovery of artifacts associated with the early children’s educational market. Nonetheless, early table-games remain among the rarest of archival objects from the romantic era.[6] This might seem surprising, given how popular they once were: the publisher John Betts claimed in 1816 that demand for his games “reached the Twelfth Thousand” (Whitehouse 4). But the scarcity of these early table-games is a testament to the status of printed materials as distinctively social media. Not only the rules and guidelines for these games, but even (or especially) their artifactual afterlives bear witness to the fact that interactivity was a feature of printed material well before it became the defining characteristic of the digital/hypertextual world. Once a game left the seller’s shop and entered into the daily lives of its buyers, it was subjected to a process of deterioration quite different from that of even the most recklessly handled books. Games were understood from the get-go as ephemeral objects; they got used, often by children, presumably quite roughly—a fact underscored by the withered corners of even the best-preserved examples. Their fate was to be used-up and discarded, replaced by either a reprint or by the new game on the market.

Ambitious digital archiving projects, such as that being undertaken for the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, have responded to the fascination and fragility of these artifacts by making their rich visual details widely available online. Digital reproduction, which arrests the artifact’s physical deterioration better than even a glass museum-case could do, is in some sense a miracle of preservation. But it cannot, of course, reproduce the distinctive artifactual character of these games—which were, after all, designed not merely as texts to be read or as engravings to be ogled but as toys to be handled, unsheathed and unfolded, manipulated, touched, refolded. The process of digitization, though, fruitfully raises some of the archival questions that early table-games present the student of material culture. How best to share these precious artifacts of everyday life with scholars and with the wider public? How to classify them? Are they literary texts or works of visual art (or both? neither?)? How should their various components—teetotums, rules-booklets, slipcases—figure in their material presentation?

Such classificatory and presentational questions might seem fundamental, yet they begin to suggest the wider difficulties that table-games, as a distinctive category of ephemera, have faced in their posthumous existence as archival objects. In tandem with the scholarship that first lifted the study of historical children’s literature out of the cloistered sphere of collectors, cataloguers, and bibliophiles (Ruwe vii), some of the most innovative rethinking of the traditional taxonomies that separate books (“literary” works especially) from artworks, or toys, or instruments, has been (and is being) done by the institutions that deal with ephemera. With the conventional categories still largely in place, it is instructive to consider the various ways games are treated and categorized by the rare-book archives and children’s libraries that hold and manage them. At the Cotsen Children’s Library in Princeton, early table-games are maintained as part of a collection of children’s toys. At Stanford’s Department of Special Collections, they are catalogued among “early books” but given lavish bibliographical entries that convey the distinctive pleasure of the archival ekphrasis. The Cornell Rare and Manuscript Collections catalogue describes early table-games as “Kits”—a strategy that seems apt, considering that they were multimedia productions, consisting not only of the engraved and colored game-sheet mounted on linen but also of various other components. Their manufacture required a variety of participants, most of whose identities subsequently vanished into the name of the publishing conglomerate that coordinated their diverse labors. Although this is a basic fact about such games, it nevertheless complicates their preservation in an archival/museal system that remains, for the most part, structured around the idea of a single author, artist, or maker.

Afterlives of ‘Human Life’

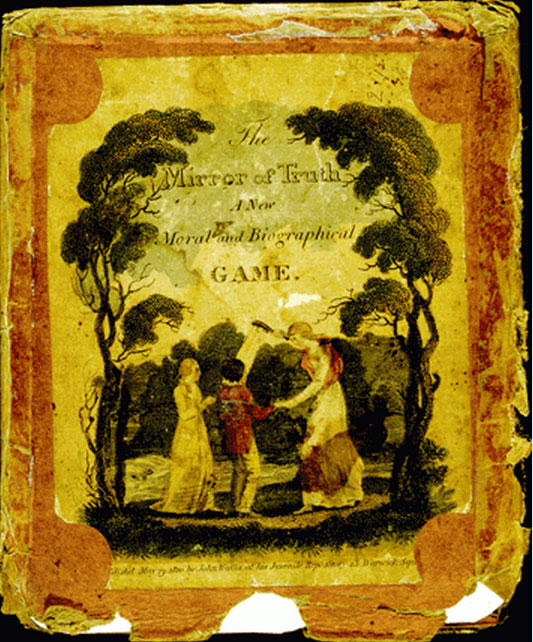

With The New Game of Human Life helping to open the British market for such pastimes, the genre of the race-game blossomed across the next several decades. Many, like Human Life, focused on moral instruction, with titles that were sometimes spectacularly didactic: The Reward of Merit (1801), The New Game of Virtue Rewarded and Vice Punished (1818, with illustrations by George Cruikshank), and The Mirror of Truth: Biographical Anecdotes and Moral Essays calculated to Inspire a Love of Virtue and Abhorrence of Vice (1811), to name just a few. The latter, published by Wallis in January 1811, is representative of the type. The Mirror of Truth was sold in a decorative slipcase, fronted by a richly colored illustration (bearing some resemblance to Blake’s title-page vignette for Songs of Innocence) of two children in a grove with an older female figure—possibly a nurse, angel, or teacher (Fig. 4). Inside was a playing-sheet, a cloth-backed engraving mounted in nine sections, consisting of 45 spaces. Each space matched a particular virtue or vice—virtues were illustrated, vices shown only by name (e.g., “Envy,” “Ingratitude,” “Impiety”)—and was paired with a historical or biographical anecdote printed in an accompanying booklet. Players advanced by spinning a totum. As with The New Game of Human Life, there was a paradoxical calculus to The Mirror of Truth’s luck-of-the-draw game-play, as moral virtue was aligned with success, moral probity with failure. A player landing on a space titled “Disinterestedness” would read a story about a man who, having been offered money to save a family stranded amidst a flood, rows out to them, plucks them from certain death, and then astonishes the gathered crowd by rejecting the proffered reward, declaring: “I will not sell my life, my labour is sufficient to support myself, my wife, and children. Give your money to this poor family, who have lost their all, and are in greater need of it.” A player landing here was rewarded with tokens. But a player landing on “Selfishness” had to go back five spaces to “Generosity,” and stay put there for a turn.

The educational objectives of some games went in a more scholarly direction, as we see in such titles as Arithmetical Pastime (1798), The Pleasures of Astronomy (1804), and Mythological Amusement (1804). There were also numerous map- and travel-related games, which traced their lineage to the earliest recorded English race game—A Journey Through Europe; or, The Play of Geography, designed by a Westminster geographer and writing-master named John Jeffreys and published by Carington Bowles in 1759 (Whitehouse 6; Shefrin, “Make It a Pleasure” 259). A nationalistic agenda was invariably in play, especially in these touristic games. For instance, Geographical Recreation (published October 1809) carried celebratory depictions of English power on its slipcase and on the playing-sheet itself, where the four corners of the world are represented with an idealized Britannia clearly on top (Fig. 5). A detail from the same game juxtaposes images of French and British “eaters”: the Frenchman (space 24) eats “soup-meagre, frogs, and salad” (players who land here must “Pay two to the pool”); the Englishman (space 25) “regales on roast beef and plum pudding” (players who land here “Receive one from the pool”). Nationalism could be made fun, and this is an important aspect of such games: as in the exploding popularity of nursery rhymes, the stress was on the compatibility of amusement with instruction.

The tacit stress, of course, was always on selling more games. The rule-booklet accompanying Geographical Recreation begins with an advertisement for 17 other games issued by John Harris’s publishing house and closes with a list advertising books that “may be deemed useful Appendages to THIS GAME,” plus forty additional books sold at his shop. The winner of The Royal Game of British Sovereigns (1820), arriving at the board’s centerpiece, was instructed “to proceed immediately to the Publishers to purchase another game equally instructive and amusing” (quoted in Whitehouse 26).

By the time Wallis’s son Edward issued (without Newbery’s collaboration) a follow-up to Human Life, such games were staples of the children’s market. The reissue, which first appeared sometime between 1815 and 1820, condensed the 1790 original down to a sixty-seven-part race culminating in “Glory.”[7] To keep up with the conventions of similar games, instructions and rationales were removed from the suddenly spacious and stylish playing surface and exported to an accompanying booklet. The updated Game of Human Life shed its eponymous novelty, even as it grew a second name: the slipcase, as often happened, broadcast a flashier title, with the ornately printed words “Wallis’s Fashionable Game of the Seven Ages of Human Life” (Fig. 6).

Over the next forty years, “the game of life” took on a varied career. In late 1821 a rival publisher’s light-hearted variation, The New Game of Life in London, illustrating Sir Patrick O’Frollic’s Amusements in London, was sold “at all the principal Toy shops.” The year 1830 saw Leitch Ritchie publish an oft-reissued novel called “The Game of Life,” and in the 1850s a detective fiction (by William Russell, under the pseudonym “Waters”) and a comic play (by John Brougham) appeared under the same title. The most famous incarnation, though, was to come across the Atlantic in 1860. As Abraham Lincoln campaigned to lead a young and fraying nation, a twenty-three-year-old lithographer named Milton Bradley made good money hawking prints of the clean-shaven candidate’s portrait (see Lepore xv-xix, xxvii-xxix). But when Lincoln grew his iconic beard, the young businessman was out of luck; the portraits suddenly unmarketable, Bradley burned them all (Shea 56). Seeking another outlet for his entrepreneurial spirit, he looked to a friend’s recent gift of an old table-game from England (its title went unrecorded), and he found in it a pattern familiar to him as that of his own life and of many acquaintances—“checkered, hazardous, uncertain in its outcome” (Shea 48). Bradley set about producing a version for the American market, and by the end of 1860 he published the game that would make his fortune. Within a year, The Checkered Game of Life sold over forty thousand copies (Lepore xxix), forming the cornerstone of the gaming empire behind such mainstays of twentieth-century American leisure as “Twister,” “Parcheesi,” and “Candyland”—not to mention “Life.” Milton Bradley himself, secure in his wealth at a relatively young age, turned his attention to other causes, educational reform chief among them. The pioneering firm that went by his name may have found its origins in what seems, at a glance, a quaint world of late eighteenth-century children’s games. But the eventual fate of the Milton Bradley Company—since 1984 a subsidiary of the multinational behemoth Hasbro, Inc.—is an apposite reverberation of the same, fiercely competitive publishing world, comprised by Bettses and Wallises and Harrises and Newberys and countless other London book-makers and book-traders who first brought the market for children’s games to life.

Appendix

Notes

- An 1811 catalogue by John Harris, Newbery’s former business manager who eventually took over the shop at the corner of St Paul’s Churchyard, advertises The Game of Human Life for six shillings in a slipcase (Whitehouse 80). The absence of recorded examples of an 1811 Human Life under Harris’s name indicates that he was reprinting old copies; given the game’s popularity—and by 1811, its age—he likely was not selling off old stock. On “The Newbery-Harris Succession,” see Appendix 2 in Darton (333).

- The Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University holds fully hand-colored, partly colored, and uncolored versions of the game.

- Waddesdon Manor holds copies of many French eighteenth-century games, and even a handful of pre-1700 ones, including The Game of the College of Litigants (L’Ecole des Plaideurs, c. 1685), a satire on the legal bureaucracy, which a client could play while waiting to meet with his lawyer (Jacobs 5); The New Game of Geography of Nations (Le Nouveau Jeu de Geographie des Nations, 1675), a game that humorously personifies various European countries (Jacobs 9); The Game of War (Le Jeu de la Guerre, c. 1698), which taught players about recent innovations in warfare under Louis XIV (Jacobs 15); and the self-explanatory Game for Learning Heraldry (Carte Methodique pour apprendre aisement le Blason, c. 1700). See Jacobs; Ciompi and Seville.

- Different sources give different dates for this game, but the Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon (which owns it) suggests 1779, and the British Museum catalogue entry dates Crépy’s obtainment of a license to 1779, which makes this date most likely.

- Mäyrä refers to this as “the so-called ludology-narratology debate” (8), adding that “No one actually seems to be willing to reduce games into stories, or claim that they are only interaction, or gameplay, pure and simple, without any potential for storytelling” (10).

- While it cannot be the case that, as the WorldCat database has it, only fourteen participating institutions around the world possess a 1790 copy of The New Game of Human Life, that small number does indicate the relative rarity of the item. (Its rarity is also suggested by a 1929 Parisian auction catalog, which lists Human Life as the second-priciest item among table-games, more than twice the cost of the next most expensive [Whitehouse 82].) In addition to the recorded instances on the WorldCat database, there are copies at the Museum of London viewable in their online collections and at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, whose website notes that “Only c. 100,000 of an estimated 1.5 million items in the John Johnson Collection [of Printed Ephemera] have been catalogued.” One should keep in mind, as well, that as ephemera, games can circulate rather quietly on the market. Last February, a rare-book dealer in Brooklyn purchased a copy from a German bookseller (private correspondence); and on websites such as “boardgamegeek.com” one sometimes discovers the existence of these archival treasures in unexpected places.

- This date-range, given by the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University, is inclusive of the dates suggested by other archival institutions; I have not seen any documentation to indicate a more specific dating.

Works Cited

- Alderson, Brian. “New Playthings and Gigantick Histories: The Nonage of English Children’s Books.” Princeton University Library Chronicle 60.2 (1999): 178-95. Print.

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “The Book on the Bookseller’s Shelf and the Book in the English Child’s Hand.” Culturing the Child, 1690-1914: Essays in Memory of Mitzi Myers. Ed. Donelle Ruwe. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2005. 3-28. Print.

- Ciompi, Luigi, and Adrian Seville. Giochi dell’Oca e di Percorso. n.d. Web. 29 Jul. 2014. <http://www.giochidelloca.it>.

- Comay, Rebecca. Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2010. Print.

- Darton, F. J. Harvey. Children’s Books in England: Five Centuries of Social Life (1932). 3rd ed. Ed. Brian Alderson. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 1982. Print.

- Edgeworth, Maria, and R. L. Edgeworth. Essays on Practical Education. New ed. 2 vols. London: R. Hunter, 1815. Print.

- Ferguson, Adam. An Essay on the History of Civil Society. 4th ed. London: T. Cadell; Edinburgh: A. Kincaid, W. Creech, and J. Bell, 1773. Google Books. Web. 28 Jul. 2014.

- Geographical Recreation: A Voyage Round the Habitable World. London: J. Harris, 1809. Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA.

- Hacking, Ian. The Taming of Chance. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. Print.

- Hannas, Linda. The English Jigsaw Puzzle, 1760-1890. London: Wayland, 1972. Print.

- Hirschman, Albert O. The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism Before its Triumph. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977. Print.

- Jacobs, Rachel (curator). “Playing, Learning, Flirting: Printed Board Games from 18th-Century France.” Exhibition handbook. Waddesdon, UK: Rothschild Collection, 2012. Web. 3 Aug. 2014. <http://www.waddesdon.org.uk/assets/PDFs/Exhibition%20pages/Board%20Games_b.pdf>.

- “Jean Baptiste Crépy (Biographical Details).” The British Museum. The British Museum, n.d. Web. 3 Aug. 2014. <http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=92592>.

- John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera. Bodleian Libraries. University of Oxford. Digital Database. Web. 3 Aug. 2014. <http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/johnson>.

- Kelley, Theresa M. “Romantic Temporality, Contingency, and Mary Shelley.” ELH 75.3 (2008): 625-52. Print.

- Koselleck, Reinhart. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. Trans. Keith Tribe. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985. Print.

- Lepore, Jill. The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012. Print.

- Locke, John. Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693). Ed. J.W. Yolton and J. S. Yolton. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. Print.

- Mäyrä, Frans. An Introduction to Game Studies: Games in Culture. Los Angeles: Sage, 2008. Print.

- Newbery, Elizabeth. Newbery’s Catalogue of instructive and amusing publications for young minds, etc. London: J. Cundee, 1800. Google Books. Web. 8 Aug. 2014.

- Plumb, J. H. “Commercialization and Society.” The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England. Ed. N. McKendrick, J. Brewer, and J. H. Plumb. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982. 265-334. Print.

- Pocock, J. G. A. Virtue, Commerce, and History: Essays on Political Thought and History. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 1985. Print.

- Roscoe, Sidney. John Newbery and his Successors 1740-1814: A Bibliography. Wormesley, Hertfordshire: Five Owls, 1973. Print.

- Ruwe, Donelle. “Introduction.” Culturing the Child, 1690-1914: Essays in Memory of Mitzi Myers. Ed. Donelle Ruwe. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2005. vi-xiv. Print.

- Shea, James J. and Charles H. Mercer. It’s All in the Game. New York: G. P. Putnam, 1960. Google Books. Web. 14 Aug. 2014.

- Shefrin, Jill. “Elizabeth Newbery.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 60 vols. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and B. Harrison. Vol. 40. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 2004. 570-71. Print.

- —. “‘Make It a Pleasure and Not a Task’: Educational Games for Children in Georgian England.” Princeton University Library Chronicle 60 (1999): 251-75. Print.

- The Game of Human Life [Wallis’s Fashionable Game of the Seven Ages of Man]. London: E. Wallis, [c. 1815-20]. Cotsen Children’s Library, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

- The Mirror of Truth: Biographical Anecdotes and Moral Essays calculated to Inspire a Love of Virtue and Abhorrence of Vice. London: J. Harris, 1811. Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA.

- The New Game of Human Life. London: J. Wallis and E. Newbery, 1790. Cotsen Children’s Library, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

- The New Game of Life in London, illustrating Sir Patrick O’Frollic’s Amusements in London. London: I. & E. Bielefeld and Payne & Son, 1821. Toronto Public Library Catalog. Web. 3 Aug. 2014. <http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDM335852&R=335852>

- The Royal Game of British Sovereigns: Exhibiting the Most Remarkable Events in Each Reign from Egbert to George III. London: J. and E. Wallis, and J. Wallis, Jr, [c. 1820]. Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA.

- Voltaire [François-Marie Arouet]. Œuvres complètes: Correspondance. [Ed. Louis Moland.] Vol. 6: 1753-1756. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1880. Google Books. Web. 8 Aug. 2014.

- Wallis, J. and E. Newbery. Booksellers’ advertisement for “The New Game of Human Life.” London: J. Wallis and E. Newbery, [1790]. University of Oxford. Digital Database. Web. 29 Dec. 2014. <http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/johnson.>

- Whitehouse, F. R. B. Table Games of Georgian and Victorian Days. London: Priory Press, Ltd., 1971. Print.

Originally published by BRANCH Collective (March 2015) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.