Defense and other spending for the American colonists.

By Dr. Julian Gwyn

Former Professor of History

University of Ottawa

One of the more intractable problems facing historians of the pre-industrial economy relates to the balance of payments. There is the usual problem of the absence of suitable statistics. There is, for instance, an abundance of data about commodity trade especially with foreign states, which include imports and exports as well as re-exports. But data on the other element in a nation’s current account-invisible trade-were not collected by governments in most cases until the twentieth century. As a result, historians have tended to confine themselves to comments about the balance of trade, and to ignore the more important question of the balance of payments. Moreover, as in so many aspects of economics, the theory of the balance of payments is presently subjected to much discussion and some dispute. In general it was (and perhaps still is) assumed that a positive balance of payments is good, and an endemic adverse balance is bad, for an economy. Yet a deficit in the balance of payments is not necessarily bad nor a surplus good for a state. A deficit is a form of borrowing which could be employed to enhance domestic savings to boost investment to the benefit of future growth. By contrast if the deficit is occasioned by an excess of aggregate demand, an economy could be said to be heading for trouble, if the practice became chronic. A knowledge of aggregate demand then becomes crucial, for it largely determines the levels of production and employment, and thus becomes the critical measure of the relative health of an economy at given intervals. To estimate aggregate demand for pre-industrial economies, where governments collected none of the necessary statistics, is an almost hopeless task for economic historians. Marginally less difficult are estimates of invisible trade.

The economy of British North America in the generation before the War of Independence is a case in point. Useful statistics of merchandise trade, except for a five-year interval from 1768 to 1772,1 exist only for commerce between the colonies and the mother country. In general they show a large commodity trade deficit, for most colonies in most years, in favour of Great Britain. The traditional but erroneous explanation of how such deficits were met was found in American commodity trade to the West Indies.2 Thus it was argued, again wrongly, that there was little need for movements of bullion in the North Atlantic commerce, as there was, for instance, in the trade to Russia, India and the East generally.

Adequate discussion of invisible trade, and hence the balance of payments in colonial America, dates only from research begun fifteen years ago. Such research found that the colonial deficit was met partly by trading favourably elsewhere, especially in Europe south of Cape Finisterre, partly by the income from services to overseas customers, and partly by capital inflows into America. For 1768-1772, by way of example, the annual average deficit on commodity trade was first estimated at £1,331,000. With £610,000 earned annually from shipping services, £400,000 from defence spending in America by Britain and £220,000 from other invisible earnings, all but £99,0003 of this huge annual deficit was accounted for. From an accountant’s viewpoint this was more or less a balanced budget.

It will surprise no one, least of all the authors of this original research, that each of these figures needs correcting. Such is the fate of all worthy pioneering works! It is one of the certain indications of the importance of their work that it should have stimulated new attempts to analyse the colonial economy of the eighteenth century. Much of the revisionary work has been undertaken by Dr Price of the University of Michigan. It was he who first made available to historians the data for Scotland’s trade with America.4 When that is added to the trade of England and Wales, the American deficit was reduced for the years 1768-1772 by 14 percent, or £189,000 annually. For certain colonies, such as the tobacco colonies of the Chesapeake, his Scottish data turned what had been regarded as colonial deficits into trade balances favouring the colonies.5 More recently his analysis of the sale of American-built ships in Britain has added (at the very least) £40,000 annually to Shepherd’s and Walton’s estimates of invisible earnings by Americans.6

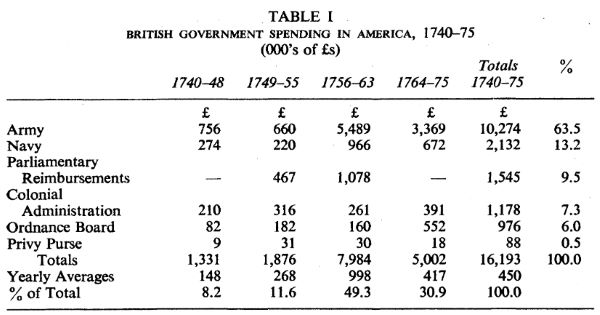

The first main purpose of this contribution is to refine the earlier estimates of defence spending by Britain in America. British spending in the colonies by the government, though largely for defence, was not confined to the army and navy and the Board of Ordinance. Estimates contained here include as well expenditures for Indian services, and payments administered by certain colonial governors and agents for such important frontier colonies as Nova Scotia and Georgia, Quebec (from 1760), and the Floridas, West and East after 1763. It also takes note of reimbursement by Parliament of certain colonial wartime expenditures, and finally some small payments made from the King’s privy purse. The sources for this more refined data are available mostly in the Public Record Office at Kew. They include the audited accounts of the army and Board of Ordnance in Audit Office papers, and for the navy the Navy Board and Victualling Board bill books in the Admiralty Papers, as well as the in-letters of the Navy Board. In addition the papers of the Treasury Board were studied for this thirty-six year interval. Two important printed sources were also employed, the appropriate volumes of the Journals of the House of Commons, and a parliamentary session paper for 1868-69, Vol XXXV, which summarised year by year, public expenditure for the eighteenth century. All information relating to spending in America was recorded and

The period 1740-8 was one of war with Spain and (after 1744) France. As far as the American colonies were concerned the years until 1744 were characterised by rather low levels of British governmental expenditure. Thereafter, especially as a result of the successful siege of Louisbourg and the establishment of a North American naval squadron in 1745, spending rose rapidly to heights never before attained in North America. With the decision in 1745 to garrison Louisbourg with regular British regiments brought from Gibraltar, together with the preparations throughout 1746 for an invasion of Canada, a project not abandoned until 1747, governmental spending remained at a high level until hostilities ended.

Though the years 1749-55 were ostensibly ones of peace, British public spending in America continued well above pre-1740 levels. This arose partly from the decision to compensate the colonies for their 1745-7 wartime expenditures, and partly from the decision to garrison Nova Scotia, after Louisbourg was restored to the French. The cost of maintaining regulars in Nova Scotia together with the expenditures incurred in building the new town of Halifax ensured that costs would rise when compared with the period 1740-8.

The return of war between 1756 and 1763 necessitated outlays in America on a scale that dwarfed the war effort between 1744 and 1748. They represented the greatest imperial expenditure at any time before the War of Independence. With unprecedentedly large bodies of troops stationed in America and large squadrons of warships, demands for funds from Parliament seemed endless. The policy of reimbursing colonies for at least a significant part of their own costs also added to the overall expenditure. The peak was reached in 1759-1760. Yet even afterwards, owing to the need to maintain an army of occupation in Canada, and on the western frontier, spending levels remained higher than had been experienced before 1755.

The years 1764-75 were ones generally of retrenchment, at first somewhat delayed by the need to contain the Indian threat led by Pontiac, and later by the decision to maintain a standing army in America, not on the frontier but in the cities and against the Americans. There was an abrupt reversal of policy from rebates to the colonies out of taxes collected by Parliament in Britain to a demand that part of the cost of this standing army in America be borne by the colonists themselves. Average spending in this period was swollen by the build-up of forces in Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775. In all, this kept spending levels substantially above those of the earlier periods 1740-48 and 1749-55. The details for the entire period 1740-1775 are summarised below in Table I.

What can be learned from these figures? The importance of spending on the Seven Years’ War is clear. Almost half the total spending for the thirty-six years of this study occurred during that brief period 1756-3. Annual expenditure reached an average of almost £1 million, when the overall 1740-75 average was only £450,000. Wartime spending between 1756 and 1763 was almost six times as large as spending during the earlier war of the Austrian Succession 1740-8. Furthermore, while annual spending for 1764-75 dropped to about 40 percent of the annual wartime totals, nevertheless it continued at a level almost 65 percent higher than for the pre-war years of 1749 to 1755.7 Thus the change of British policy in America, if the serious spending of money by Parliament is a reasonable guide, can be said to date not from 1756-63, as is traditionally recorded, but from 1745-6 with the Louisbourg expedition and the planned invasion of Canada. From that moment onwards spending levels acquired an altogether new momentum, from which the British government did not free itself for the rest of the eighteenth century, even after 1783, owing to the need to defend Canada. Moreover, the data show that it was the expense of the army, with its ancillary arms of the artillery and engineers under the Board of Ordnance, which constituted the bulk of the cost, a shade under 70 percent, or more than five times the expenditure on the navy in America. Of the £ 1.2 million spent in America for colonial administration, the bulk went on Nova Scotia, some £618,000, or about 53 percent. By contrast Georgia received about £252,000 and Quebec £125,000, or about 21 and 11 percent respectively of that item of expenditure. A great deal of the Nova Scotia expenditure was for goods and services supplied by New Englanders, chiefly from Massa-chusetts, and those of Georgia by South Carolina merchants.

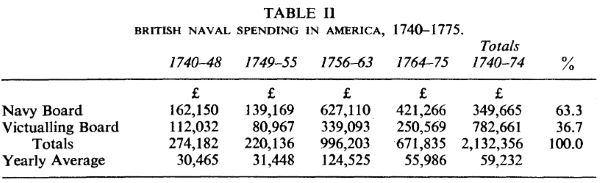

Though there have been estimates of defence spending made by other historians, perhaps the most interesting by John Shy,8 it is naval spending that most confused earlier attempts to come to some sort of reasonable conclusion. It might therefore be useful to provide a few more details concerning naval spending in America. The first thing to notice is that the total naval expenditure in America were but a relatively small fraction of the estimated total cost of maintaining the navy in American waters.9 The cost of shipbuilding was a benefit to English shipbuilders, while Americans were given the crumbs when ships on the North American station needed repairs. The pay of seamen was largely effected in England and was thus of no benefit to Americans. Usually the first six months’ victuals were taken on board warships leaving England for America. It was only after these rations needed replenishing that American suppliers were called upon. Still the principal expenditures by the navy in America were for provisions, administered by the Victualling Board under the Navy Board by contract with suppliers in various specified American ports, and for repairs to naval vessels, administered by the Navy Board, and carried out at the request of naval captains on the spot and without benefit of fixed price contracts. Of less significance were the annual expenditures for sick and wounded seamen, who recuperated ashore, or for Americans who acted as pilots on entering and leaving American ports, in the St Lawrence river and along the entire American coast. Other significant expenditures in America focused from 1759 on the building of a naval base at Halifax, and on the hiring of transport vessels from American owners to move both troops as well as their equipment and provisions. In addition the Navy Board ordered yearly payments to American suppliers of naval stores, either shipped directly to England or to the West Indies squadron, based at Jamaica or Antigua. Such stores included masts and bowsprits, pitch, tar and turpentine, and, increasingly from mid-century, American iron. The Admiralty also paid bounties to American captors either of enemy warships or privateers, based on the complement of the captured enemy vessel. In this way American privateers, especially from New York, earned occasional sums, quite independent of prize money. Details are found in Table n below.

A word of explanation is perhaps needed for seamen’s pay. For the purpose of these estimates it has been assumed that the few seamen, privileged with shore leave while serving off North America, managed to steal as much as they spent from the minute sums they were allowed before their ships were paid off in England.10 In this way the economic impact on America of naval pay was neutral. This is in marked contrast to soldiers and sappers, whose pay was given them more or less regularly in America and who disposed of it locally to the great benefit of the colonists. Naval officers, by cash or through credit, obviously spent some of their income ashore in America. It has been assumed here that, as with public servants everywhere, they charged most of their expenses to their government, which left their private spending at such a low level that it can safely be ignored. If a guess was required, an additional amount of perhaps £2,500 a year (or £90,000 for the entire thirty-six year interval) might be added, a sum which would add about 4 percent to overall naval expenditure in America.

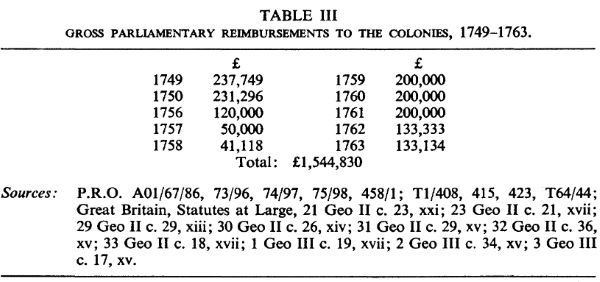

Another little considered but important aspect of American invisible earnings were the reimbursements to the colonies for part of their military costs, rebated to them by Parliament, as so-called ‘free gifts’. In 1749-1750 Parliament voted some £467,000 to compensate the colonies for their costs relating to the defence of Nova Scotia in 1744, when Annapolis Royal was under attack, the attack and garrisoning of Louisbourg in 1745-1746, and the planned, but abortive, assault on Canada in 1746-7. Details of these and later grants are noted in Table III below.

The first point to note is that these are gross figures, and thus somewhat overstate the amounts actually sent to colonial treasurers. It is known, for instance, that of the £183,649 granted to Massachusetts in 1749, some £179,260 or 97.6 percent of the gross sum actually reached the province, the balance going in fees and commissions.11 Again, of the £120,000 voted by Parliament in 1756 for the colonies, about £114,659, or 95.5 percent actually reached the shores of America.12 If these figures are an accurate guide then perhaps it can he assumed that not less than 2.5 percent of the gross grants made by Parliament remained in the hands of English agents and officials, and Royal Navy officers by way of fees, commissions and freight money, for a total of £38,621, thus reducing the reimbursements to £1,506,209 net. The lion’s share naturally went to those provinces most deeply involved in the war efforts. Massachusetts received over £624,000 gross, with Connecticut and New York trailing far behind both with less than £250,000 each. The least active, of course, were the southern colonies, far removed from the principal theatres of war. It might also be suggested that later complaints in the 1760s over Parliament’s attempts to tax Americans directly to support the cost of maintaining a squadron off the continent and an army ashore were in direct proportion to the degree of largesse they had enjoyed from that same Parliament for precisely the same purpose. Such a drastic change in policy between 1764 and the year earlier, carried out without consultation with the colonial assemblies, could only have been pursued by ministers insensitive to American experiences.

It remains to be seen how British spending in America was conducted. There were two principal methods: by drawing bills of exchange on various government offices in England, and by shipping specie to America. As to the first method, a number of colonial governors regularly drew sterling bills to meet local government needs. Such, for instance, was the case of Georgia throughout its colonial history, where there is no evidence that any specie shipments were ever officially forwarded. The same practice was followed when Louisbourg was occupied between 1745 and 1749, though part of the demand for specie was offset by the ready availability in 1745 of Spanish dollars seized from prize vessels condemned there. Later, when the government of Nova Scotia established itself at Halifax, expenditure was carried on in large measure by drawing sterling bills, though again some specie circulated-indeed the first governor brought out a small quantity with him. All the colonies involved in the abortive Canada expedition in 1746-7 paid for their costs by drawing such sterling bills. Later, after the conquest of Canada in 1759-1760 and the session of the Floridas in 1763, the practice spread as by far the more convenient and secure method of making international payments. All the commanders-in-chief in America, from Braddock in 1754 to Gage in 1775, adopted this practice, which incidentally both ordnance and Royal Naval officers in America had traditionally followed. Whatever the office named in the bill of exchange, whether the Paymaster General, the Navy Board, the Victualling Board, the Transport Board, the Sick and Hurt Board, the Board of Ordnance, ultimately all bills drawn in America had either to be accepted or rejected (for lack of adequate vouchers) by the Treasury Board, and balances struck, all of which accounts were then eventually approved by the officers of the Audit Office.

The proportion of British spending in America met by shipping specie to the colonies is somewhat difficult to determine. In general, contractors to the Treasury for the supply of pay, subsistence or victuals in America were reluctant to send coin across the Atlantic, even when they were able to charge their costs of freight, handling and insurance to the government. Normally, through their agents in America, they drew bills which were sold to American merchants or British officers in America either for cash or for goods or services rendered. From time to time, when the specie situation became difficult in America, whether at Quebec or Montreal, Louisbourg or Halifax, Boston, New York or Albany, early notice was given and shipments were dispatched from England carrying Spanish milled silver and Portuguese (Brazilian) gold coin. Such shipments amounting to at least £1,885,426 or £52,373 for each of the thirty-six years under analysis here, can be verified. This amounted to roughly 12 percent of overall British spending in America. The bulk of such payments occurred during the Seven Years’ War, though the first significant shipment of this kind had been made in 1749, when Massachusetts received more than £179,000 in specie by way of parliamentary rebate for the cost of taking and garrisoning Louisburg. It ended, as far as this study is concerned, with the rapid build-up of troops in the colonies late in 1775, and by the shipment of large additional amounts of specie to meet the requirements of army pay and subsistence. 1775 was in many ways, from the administrator’s and contractor’s view, a repetition of 1755, except this time it was unclear how eager the merchant communities of the port towns would be to feed at the trough provided by tb.e Treasury Board, as it carried out the orders of Parliament. It quickly transpired, of course, that at all times American and Canadian merchants were eager to do business with the Crown’s agents, who together represented the most considerable merchant banking business on the continent.

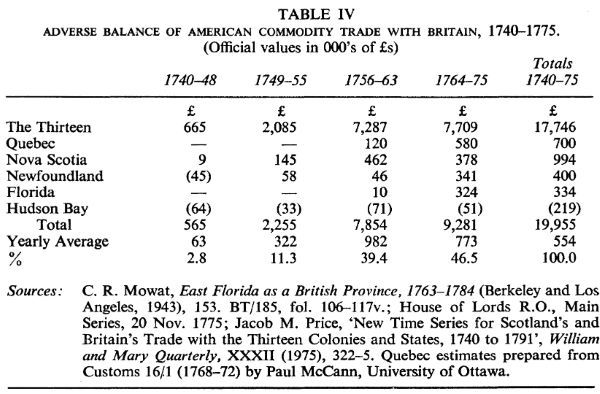

The data on overall British government spending in America could be analysed at much greater length, but their more important significance will be illustrated rather when that expenditure is related to the overall current account of the American colonies. The £16.2 million spent between 1740 and 1775 by Britain to administer and defend her colonies went a very long way to balance the continent’s deficit in commodity trade with the mother country. In a word, much of the government’s spending in America was employed to pay for imports from Britain. The aggregate adverse balance of trade is detailed in Table IV below. Data is arranged as in Table I, in the same intervals of war and peace. The total deficit, amounting to more than £20 million, developed principally from 1756 onwards. Of this huge sum fully 89 percent was generated by the Thirteen Colonies, about 5 percent by Nova Scotia and 3.5 percent by Quebec. Historians are generally wary of these official values for trade; and it is my considered opinion that in general they seriously underestimate the value of American goods imported into Britain. Nevertheless they remain the best available data.13 If they bear any relation to the flow of commodity trade, then the Thirteen Colonies per capita had a far lower trade deficit than had Quebec, Nova Scotia or Newfoundland.

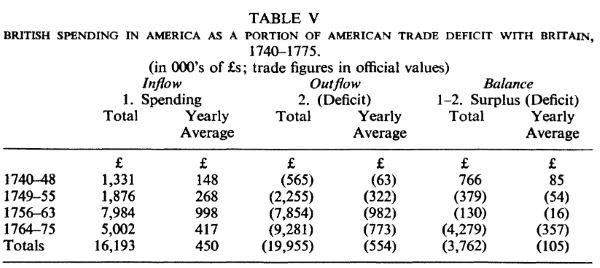

However, of far more importance than any prolonged discussion of the distribution of that deficit, is the relation it bears to the overall balance of payments. So let us now compare these net deficits in the colonial trade with Britain (an economic outflow) with net spending by Britain in America to administer and defend the empire (an inflow of invisibles). The comparative data, in simplified form, is presented in Table V. From the Table it is clear, if the trade figures have any approximate relationship to the real value of the goods in transit,13 that at least until 1763, except for the period 1748-55, inflows into the North American economy of British government funds to pay for defence and administration more than made up the deficit of American colonial trade with the mother country. Between 1740 and 1763 overall British spending in America was an estimated £11,191,000 while the estimated deficit in American trade with Britain was £10,674,000 for a surplus of £517,000, or about £22,000 annually.

The shift in the North American balance came with the restoration of peace after 1764, when a relatively sluggish export trade from America was overtaken by a high aggregate demand for imports from Britain. Thus it was in the dozen years before the outbreak of the War of Independence that British government expenditures in America, for the first time, failed to act as the crucial element in reducing America’s historic trade deficit with Britain. Though North American imports continued to outstrip exports to Britain, the annual gap between 1764 and 1775 was actually lower than it had been during the Seven Years’ War: £773,000 compared with £982,000. At the same time British spending after 1764, though at £417,000 yearly still far above the pre-1756 annual level of £268,000, fell by 42 percent below the war years, 1756-63. For the period 1764-75 this meant that, though more than £5 millions were spent in America, the trade deficit still surpassed this huge amount by £4,279,000, or £375,000 annually. Such a figure, though large in comparison with earlier years, was hardly ruinous, and when calculated on a per capita basis, in view of the greatly enlarged colonial population by the 1770s, was actually rather small. Moreover, it is clear from the research of Shepherd, Walton and Price, among others, that on the whole the North American colonies, as a result of their commodity trade to southern Europe and their invisible earnings in the West Indies, probably experienced with great regularity in the 1760s and 1770s a generally favourable balance of payments. Thus the trade deficit with Britain, however important, was no longer crucial to overall economic growth in the colonies.

In all of this the role of British government spending in America, a matter largely misunderstood and inaccurately estimated, became an important element. It was more than a temporary windfall, more than a passing economic feature, but, from 1740 until 1763 a decisive factor in maintaining a balance of payments favourable to the colonies. Thereafter during the 1760s and 1770s in the context of a rapidly maturing colonial economy, the importance of British government spending as an aspect of American invisible trade declined both absolutely and relatively. Yet its diminished role in no way weakened that economy, as merchants redirected their products to alternative markets, with assets greatly expanded by the Seven Years’ War, and with a confidence given clear expression in the numerous enlarged new houses that they built themselves in the growing colonial cities.14 This underscores perhaps the general success, despite political uncertainty, which North American merchants experienced in international commerce in the dozen years before the outbreak of the American War of Independence.

Endnotes

- P.R.O. London, Customs 16/1, data for which was computerised by Professor Lawrence A. Harper, Department of History, University of California, Berkeley, to whom we all are indebted.

- There was actually a deficit of some £18,000 annually on America’s commodity trade with the West Indies between 1768 and 1772.

- See especially James F. Shepherd and Gary M. Walton, Shipping, maritime trade and the economic development of colonial North America (Cambridge, 1972), 116.

- Jacob M. Price, ‘New Time Series for Scotland’s and Britain’s Trade with the Thirteen Colonies and States, 1740 to 1791 ‘, William and Mary Quarterly, XXXII (1975), 307-25.

- See Price’s review of Joseph A. Ernst, Money and Politics in America, 1755-1775. A Study in the Currency Act of 1764 and the Economy of Revolution. (Chapel Hill, N.C.: 1973) in Reviews in American History, II (1974), 367-8.

- Price, ‘A Note on the Value of Colonial Exports of Shipping’, The Journal of Economic History, XXXVI (1976), 704-24. He estimates that between 1763 and 1775 ‘ship-building in the Thirteen Colonies totalled about 40,000 measured tons annually and was worth about £300,000 sterling, of which at least 18,600 tons worth £140,000 were sold abroad’. p. 722. See Shepherd’s and Walton’s estimates of between £45,000 and £106,000 annually in Appendix VI of their book, op. cit., 241-5.

- For the period 1768-72 Shepherd and Walton roughly estimated annual defence spending at £400,000. My data are slightly different. If the cost of the army, navy and ordnance office alone are taken into account, the total is £341,000, or a difference of 15 per cent. If all civil and military expenditure by Britain in America is calculated the annual figures rise to £365,000 a 9 percent difference from their estimates. See Shepherd and Walton, op. cit., 150-1.

- John Shy, Toward Lexington. The Role of the British Army in the Coming of the American Revolution (Princeton, 1965), especially 338-40. Shepherd and Walton based their estimates on an unpublished Ms by Maclyn P. Burg, ‘An Estimation of the Cost of Defending and Administering the Colonies of British North America, 1763-1775’, a copy of which Dr Burg was good enough to send me. He was concerned with overall costs to the British taxpayer rather than the proportion spent in America. He concluded that £8.4 million was the cost between 1763 and 1775. For another estimate see Walter Scott Dunn Jr., ‘Western Commerce, 1760-1774’, (Unpubl. Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1971). See Charts H-1, pp. 253-4. His estimate is £7.7 million for the period 1759-1774, and he makes no attempt to estimate naval expenditure in America.

- In answer to a request by the Treasury Board of 4 Feb. 1767, arising from a House of Commons order on 22 Jan. 1767, the Navy prepared estimates of the cost of the Navy between 1756 and 1766 inclusive for North America and the West Indies. The totals for the West Indies came to £6,227,759, and for America £4,736,295. Of this sum of £4.7 million, I have found at least £1,493,189 actually expended in America -31.5 percent. The official estimate of £4.7 million included for wear and tear, £1,012,408, for flag officers’ pay and table money £22,180, for officers’ pay and seamen’s wages £1,287,394, for victualling seamen and officers £1,053,233, for sick and hurt seamen and officers £71,090, for transports £967,712, victualling land forces carried on board £322,279. P.R.O., Adm 49/1, fol. 5.

- Daniel A. Baugh, British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole (Princeton, 1965).

- For details see Massachusetts Archives, Vol. XX, fol. 588: ‘The Province of the Massachusetts Bay in America in Account Current with Sir Peter Warren Knight of the Bath and William Bolian Esqr’.

- There is little use in employing current rather than official values for trade. The current values have been calculated by multiplying the official values by a highly suspect commodity price index, but the one only available, and which applies only to England. Scotland has no such commodity index, and much of the American exports in tobacco were sent there, while every colony conducted some trade with Scotland.

- For the current values of American trade to Britain and their method of calculation, see John J. McCusker, ‘The Current Value of English Exports, 1697 to 1800’, William and Mary Quarterly, XXVIII (1971), 607-28.

- Evidence for this can be found in all American colonial cities from Boston south to Charleston. Much of it can be seen readily by comparing evidence of city maps in the 1740s with those of the 1760s. This subject deserves special attention.

Chapter (74-84) from The British Atlantic Empire before the American Revolution, edited by Peter Marshall and Glyn Williams (Routledge, 07.08.2005), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.