The study of late medieval sex trafficking makes clear that poverty and limited economic opportunities for women led to vulnerability, and thus to victimization.

By Dr. Christopher Paolella

Professor of History

Valencia College

Introduction

Over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, medieval Western Europe to the north of the Alps and Pyrenees experienced widespread socioeconomic changes that included urban revitalization and an expansion of the monetary economy. These changes encouraged the growth of commercial sex, which developed over the course of the thirteenth century to the point that its socioeconomic structures (brothels, bath-houses or ‘stewes,’ prostitution rings, etc.) began to be formally addressed by royal, ecclesiastical, and municipal authorities: at this point, we may now speak properly of a growing commercial sex industry. The growth of that industry would in turn create a new source of demand for labor that human traffickers were willing and able to supply.

Movement in late medieval Western European sex trafficking networks tended to be regional or local in terms of the cultural and geographical distances traversed, for example, from Valenciennes to Dijon or from Hertfordshire to London, or among and within the streets of London and Paris. Again, we must remember that trafficking is, at its heart, an exchange. As such, movement – whether across thousands of miles from China to Italy or across a narrow lane from the open space of the streets to the enclosed spaces of homes, inns, and taverns – serves to facilitate that exchange.

There were numerous points of entry into the sex trafficking webs of late medieval Europe, including familial pressure, abduction, and predatory employment. The stories of the victims, therefore, vary among individuals. Yet, common patterns emerge from the records preserved in archives across France and England: economic duress, for example, placed women and girls in precarious circumstances that human traffickers readily exploited; stiff competition for employment in industries such as food service and hospitality, laundering and embellishing, and domestic service meant that poor women and girls had few options available to them if they fell into the hands of a predatory employer.

As we turn our attention to medieval sex trafficking, we will also re-connect with Joy and Anne, and we will meet Kris and learn about her experiences in Chicago. Whether in the medieval or modern world, once a victim entered the commercial sex industry, violence kept her there, and escape was difficult although not impossible.

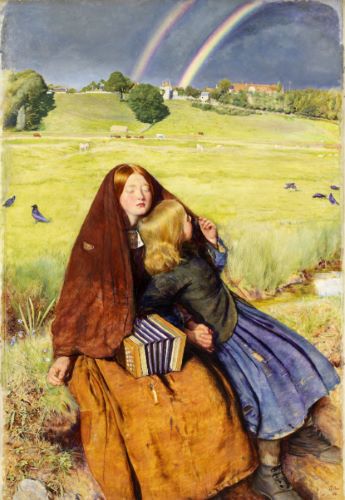

Entry into Sex Trafficking Networks: Familial Pressure

In an environment of constrained economic opportunity for women, human trafficking flourished. In both France and England, poverty could compel mothers to prostitute their own daughters. Fathers were seldom accused of such activity, which suggests both a systemic bias against women where crimes against public morality were concerned, and a particularly acute financial vulnerability that single mothers experienced when deprived of a husband’s income. For example, in a survey of 130 cases of sex work in Dijon between 1440 and 1540, Jacques Rossiaud has estimated that nearly all of the women had entered prostitution by the age of seventeen, and a third had entered sex work before the age of fifteen.1 Of the 77 cases where the reasons for entering sex work are recorded, a quarter of those cases involve young women who had been sold or pressured into the Dijon commercial sex industry by their families because of dire poverty. Twenty-seven percent had been victims of a public rape, and because the victims bore the shame of their sexual assault, their chances for marriage were slim indeed. Faced with the prospect of a daughter without hope of a stable financial future through marriage, families then sold them into the municipal brothel or into prostitution rings, where they might still eke out a living and relieve the household of their financial burden.

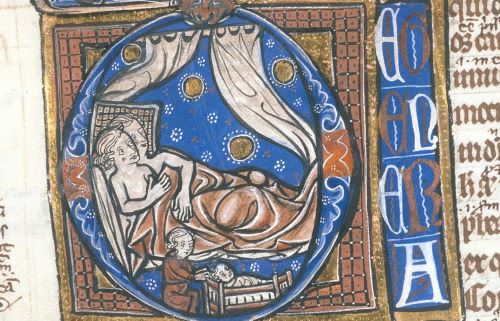

In England, in 1395, Elizabeth Brouderer (Embroiderer) was accused in court testimony of trafficking her daughter among various men over the course of a single night. According to the deposition, Elizabeth ‘brought a certain Alice, her daughter, to different men for the sake of lechery, putting her with those men in their beds at night without light.’2 In the 1470s, Joan Chapman, the widow of a certain John Chapman of Sandown in Kent, was charged with ‘bawdry’ for pimping her fifteen-year old daughter Alice to Flemish and German merchants in port.3 In 1494, Katherine ‘Dwytchwoman’ (Dutchwoman) was accused of being a bawd for her daughter, ‘because she [Katherine] beat her when the girl refused to visit the lodgings of a certain Lombard, by whom she later had a child.’4 In 1523, Agnes Castrey faced charges of bawdry on account of selling, ‘her daughter divers times.’5

In her childhood, Joy’s father was well-connected in her hometown. His reputation for prostituting his daughter spread through the community via word of mouth. He would often sell her to multiple men a night, which included school nights. When she grew older, he brought her to parties and local swinger clubs and there sold her to the guests and patrons.

Entry into Sex Trafficking Networks: Abduction

Young single women, especially those of poor or middling status, had narrow economic prospects beyond marriage within village communities, and most of those opportunities were found in medieval cities and towns. The search for employment was a moment of acute vulnerability for young women and children in the late Middle Ages, who were often driven by desperate financial circumstances into distant labor markets located in unfamiliar environments, far beyond the protection of their kinship networks. Human traffickers understood and exploited their isolation and inexperience as opportunities for profit. In 1517, for example, a tailor named John Barton stood accused of kidnapping a young woman named Joan Rawlyns. According to the court proceedings, Joan had told her patroness, the Lady of Willesden, that she wished to go to London where servant wages were higher than in Aldenham, Hertfordshire (about sixteen miles northwest of Westminster), where she lived. The Lady of Willesden consequently asked John Barton, an acquaintance of hers, to escort Joan to London. Mr. Barton confessed that he had met Joan on the highway as he came from services at Our Lady of Willesden. John promised

to bring her [Joan Rawlyns] to good and honest service in this city [London]. Whereupon she, putting her trust and confidence in him, went with him throughout the whole city until he, unbeknownst to her, had brought her to the Stewes’ side [Southwark] and there he left her in a waterman’s house, and then went immediately to a bawd there and made covenant with her to set the said maiden with the said bawd. In the meantime, the said maiden, perceiving by the said waterman’s wife that she was in such an evil-named place, knelt down on her knees and besought her for Our Lady’s sake to help convey her to this city; which accordingly she did honestly in this city, where she [Joan] now remains in honest service.6

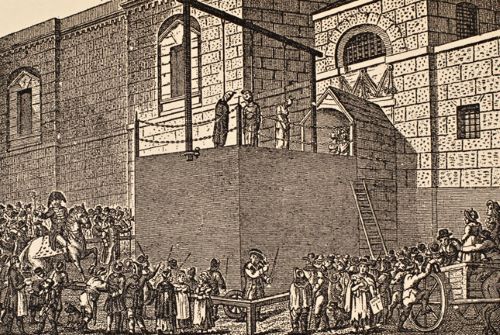

Because he had a history of ‘dishonorable transactions with women,’ the court sentenced John Barton to prison in Newgate. Later, his head was shaved, his crimes were recorded and pinned to his clothes, and then he was paraded through the town while holding the tail of a horse, as his crimes were publicly proclaimed to warn those who were illiterate. Finally, he was pilloried and expelled from the city. John’s record of ‘dishonorable transactions’ suggests that he trafficked semi-professionally, and he clearly maintained an extensive network of personal connections in London’s underworld. He knew local buyers who would conclude transactions swiftly, and he knew the safe houses where he might surreptitiously hold his abductees in the meantime. Considering that John knew to bring Joan to the waterman’s house, and given his history of ‘dishonorable transactions,’ we can reasonably presume that Joan was not the first person the pair had trafficked. Although she was able to escape and eventually find gainful employment, her story was atypical, as we shall see.

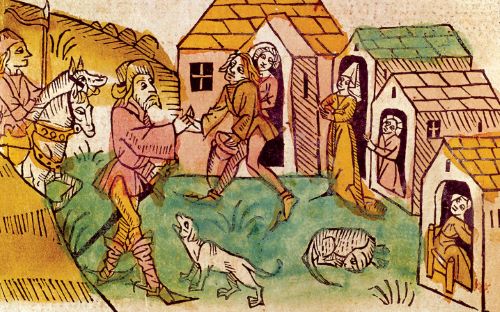

The highways were not the only haunts of traffickers; in the cities and towns of medieval Europe, they stalked the local streets. In Paris in the year 1400, Jeanne de Baugie stood accused of abducting a young girl whom she had lured into her house with the promise of employment in domestic service. During her interrogation, which included torture, Jeanne confessed to running a ‘disorderly house’ and acting as a procuress; however, when she sought royal pardon she chose not to retract her confession, indicating that the charges may well have been true.7 In the streets of Beaucaire, a woman named Catherine fell in love with a riverboatman, who as it turned out, was also a semi-professional trafficker. The man convinced Catherine to leave her husband of two years and then carried her away to Avignon, where he sold her into the municipal brothel.8 Catherine was certainly not unique, for in 1458, a bawd trafficked a woman named Jammeline from Beaucaire to Avignon. Over the next several months she was brought before the temporal courts of the city for habitual prostitution, despite official reprimands and a short stay in jail.9 Considering that regular arrests and imprisonment apparently did little to dissuade her from sex work, we must then wonder which Jammeline feared more: the jail or the anger of her pimp?

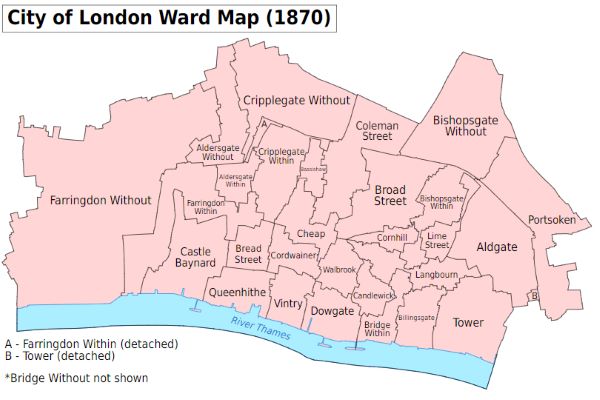

In London, in the latter half of the 1420s, Agnes Smith was charged with kidnapping and bawdry. She was accused of luring Agnes Turner, the nine-year-old daughter of lace-weaver Margaret Turner, into her home with ‘enticing words,’ where she hid a young man named Robert, a clerk of the royal Chapel of Saint Stephen of Westminster. Agnes Turner was unaware of the trap until Robert attacked her. The little girl was saved only because passersby in the street below heard her screams, broke into the house, and rescued her.10 In 1438, Peter Manyfeld was charged with kidnapping Alice Burley from her home, ‘and violently and secretly ravished her against her will, and kept her in his chamber for a long time, and after he was satiated with her, sold her to a certain Easterling at the Steelyard.’ In that same year, a woman named Joan stood accused of bawdry between ‘a certain Agnes and the Flemmings and others at the Stylyard [Steelyard].’11 According to court records, on 11 May 1439 an inquest was made regarding ‘a certain Margaret Hathewyk,’ who

often between 10 October [1438] and 20 March [1439] in the parish of St. Edmund in Lumbardstrete [Lombard Street] procured a young girl named Isabel Lane for certain Lombards and other men unknown, which Isabel was def lowered against her will in the said Margaret’s house and elsewhere for certain sums of money paid to the said Margaret, and further that said Margaret took the said Isabel to the common stewes on the bank of the Thames in Surrey against her will for immoral purposes with a certain unknown gentleman on four occasions against her will.12

In the late 1440s, a ‘stewemonger’ [brothel-keeper] named Nicholas Croke [Crook] stood accused of taking a woman named Christina Swynowe to the Southwark stews on the south bank of the Thames, ‘and by force and money compelled and enticed her to fornication and cohabitation’ for nine days.13 In 1490, Johannes Albon sold a certain Margaret to a procurer in the Southwark stews.14

Although trafficking victims were disproportionately of poor or middling status in the extant sources, and although wealth could certainly mitigate the risks of abduction, money and status were by no means the perfect protection from the dangers of traffickers. In France in 1476, for example, a young noble widow named Marie, the daughter of a local lord in Abbeville, fled with a small entourage of servants from an unwanted second marriage and arrived at Valenciennes, 100 miles east of Abbeville, where she had friends. However, while lodging at an inn outside of the town she became separated from her party and fell in with a band of young men led by a certain Drouhet, himself attached to a noble household. After raping Marie, Drouhet offered to put her in contact with his master, perhaps to buy her silence. Marie accepted his offer, although considering she was still in the company of Drouhet and his men, coercion likely played a role in her acceptance.

Drouhet and his company took Marie to Dijon and lodged at an inn there for several days, while he met with the manager of the municipal brothel, Jeanne Robelote, to arrange Marie’s sale into the house. Drouhet then told Marie that they were going to see his master, but instead he took her to the madam. As Marie became aware of the plot, she was overwhelmed with despair and begged Drouhet for mercy, but he forced her into the brothel nonetheless. As matters unfolded, Jeanne Robelote was quick to discover that Marie was of noble status and balked at possibility of becoming an accomplice in the abduction and prostitution of a member of the nobility, crimes which carried the death penalty. Drouhet was forced to return with Marie to his lodgings, and for two weeks he and his companions used her jewels and adornments to finance their daily living; all the while Drouhet beat her and threatened her life if she didn’t agree to prostitute herself. Eventually, Marie contacted a well-connected woman in Dijon who took her in and put her in communication with the municipal prosecutor. After Marie f iled a formal complaint Drouhet was imprisoned, but for unknown reasons Marie pardoned him once more by dropping the charges. Drouhet then vanishes from the public record.15

Today, as in centuries past, human trafficking continues to disproportionately affect impoverished women and children, but anyone can become a victim and a survivor. Kris, for example, came from a supportive, loving, middle-class family in the Kansas City area. As a teenager, Kris decided to explore the world; she packed her things and brought the little money she had saved to the train station. She planned to make for New York City, but could only afford a ticket to Chicago. In Chicago, a recruiter spotted her alone, isolated, and vulnerable at the train station. After learning that Kris had no friends, family, or job prospects in the area, the recruiter of fered her a place to stay and a job while she was in the city. She believed him.

Entry into Sex Trafficking Networks: Employment

Even if a young woman successfully found a position in an urban-based trade, she was not out of danger. A limited market for female labor meant that competition for employment was fierce, and with little surety of finding an alternative occupation, women could not easily leave a predatory employer’s service. The connection between traditional female labor and prostitution meant that young women and girls who apprenticed in industries associated with prostitution were especially vulnerable to the vices of their employers.

Women who laundered, embellished, or repaired clothing had access to restricted male-only living spaces such as cloisters and rectories, and were therefore popularly associated with prostitution. For example, in 1385 in London, Elizabeth Moryng was charged with operating a prostitution ring out of her embroidery shop, and of pimping the young women and girls who were ostensibly her apprentices. One of her victims, a young woman named Joan, testified that Elizabeth had retained her,

and divers other women and bound them to serve her in that art [embroidery], whereas in truth, she did not practice that art, but after she retained them she exhorted said Joan and all the other women living with her and serving her to live in lechery and to go with friars, chaplains, and all others wishing to have them.16

Joan’s testimony led to Moryng’s conviction on charges of bawdry, and she was eventually banished from London.17 In 1423, Alsoun [Alison] Bostone was sentenced to spend an hour at the pillory (collistrigium) for three consecutive market days after she was convicted of ‘having let to hire for immoral purposes’ her thirteen-year old apprentice, Joan Hammond, ‘to divers persons for divers sums of money.’18

However, the association between the sex industry and the launderesses, embellishers, and so on was not completely illogical. We may recall that in in 1338, authorities charged Juliana atte Celer and Alice de Lincoln with operating a ‘disorderly house’ in Hosierlane, outside of London’s designated red-light district. In 1395, a London prostitute named John Rykener, who dressed in women’s clothes and assumed the identity of a woman named ‘Eleanor,’ claimed in his court deposition that he had ‘stayed at Oxford for five weeks before the last feast of Saint Michael’s, and worked there as an embroideress in women’s clothing, and called himself “Eleanor”,’ and that while in Oxford, ‘three unsuspecting scholars, one of whom was named Lord William Foxlee, another Lord John, and the third Lord Walter, practiced the abominable vice with him of ten.’19 We may also recall that John Barton was a tailor and a part-time sex trafficker in sixteenth-century London and that in Paris, and that the two centers of prostitution on the right bank of the Seine, the rue de Baille-Hoeand the Court-Robert-de-Paris,were located in areas known for textile production.

Women who worked in hospitality and the food service industry were also vulnerable to exploitation from predatory employers, because taverns were closely associated with lascivious behavior throughout the Middle Ages, and thus widely held presumptions of promiscuity among tavern workers put employees at risk. For example, a local London tavern named The Pye in Queenhithe had developed the reputation as a place ‘which is a good shadowing for thieves, and many evil bargains have been made there, and many strumpets and pimps have their covert there, and leisure to make false covenants.’ Municipal authorities felt that it was necessary to recommend that the tavern be prohibited from operating at night, in order to ensure ‘the destruction of evil’ that The Pye appeared to nurture.20 In Kingston-upon-Thames, the wife of Thomas Butcher, a woman named Mariona, was accused of whoredom in association with her management of a local tavern in 1434, and several years later, in 1437, she was presented before local magistrates as ‘a strumpet.’21 In London, William Basseloy, a taverner, stood accused of pimping Thomesina Newton from his establishment in 1470, while two servants of the Busche Tavern, Mandelelyn and Alice, were procured by the proprietor. The taverness of Le Schippe acted as a bawd for one of her tapsters.22

Even if tavern owners did not directly engage in sex trafficking, they could certainly facilitate commercial sex by turning a blind eye. In 1251 in France, prostitutes, ruffians, and ‘vagabond women’ (mulier vagabunda) were prohibited from Montpellier’s taverns.23 Caustelnaudary fined both prostitutes who ate in public houses and the taverners who served them; the municipal statutes for Saint-Félix prohibited prostitutes from taverns; and throughout the late f ifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the consuls of Toulouse impressed upon their successors the necessity of barring prostitutes from the city taverns.24

In London in 1470, John Mande and his wife stood accused of pimping John’s sister at a tavern and of having networked with other bawds and prostitutes in other public houses, all apparently without any interference from the establishments.25 Taverns and inns played a central role in a tryst involving a priest and a prostitute in 1516. The prostitute, a woman named Elizabeth Tomlins, sent for the hostler of The Bell Inn to meet her at a neighboring alehouse. During their meeting, Elizabeth asked if a certain priest named Gregory Kyton was staying at the inn. When the hostler returned to The Bell Inn, he told the priest that a woman in the alehouse had asked for him, and Kyton replied that he would meet her in his room. The hostler then suggested instead that the priest go to The George on Lombard Street, and the hostler would bring Elizabeth there to meet him. Elizabeth and the hostler arrived at The George before the priest and arranged for accommodations. Gregory Kyton arrived shortly thereafter and met Elizabeth in her chamber; later, Elizabeth, the hostler, and the priest ate together at the priest’s expense.26

Domestic service was a third industry of specialized female labor that was closely associated with sex work and trafficking. In Normandy on 13 July 1333, Jacqueline la Cyriere stood accused of luring ten-year-old Jeanette Bille-heuse into her home with the promise of wages in exchange for housework. According to trial proceedings, Jacqueline hid a Lombard soldier in her home, who then raped the child with her assistance. The court ordered two matrons to examine the girl, and the brutality the women described is chilling. Under oath they testified that Jeanette, ‘was found raped and pierced through and through, and was so fearfully injured that it was horrible to see, and [Jeanette] was very ill and terribly wounded, and in every manner injured.’ The court condemned Jacqueline to death by burning at the stake, but the fate of Jeanette’s rapist is unknown.27 In Paris as we have seen, Jeanne de Baugie lured her victims into her house with the promise of employment in her service; in Dijon, of the 130 known cases of sex work between 1440 and 1540, over a third involved domestic service.28 In Toulouse, Peter and Katherine Fontanes were sentenced to corporal punishment and banishment from the town after their conviction of pimping their ten-year old domestic servant, Catherine, in 1474.29

In England in March 1437, the letter books of London record that a couple named Richard Peryn and his wife Margaret had, ‘been committed to prison,’ not only for ‘generally keeping a disorderly house,’ but also ‘for having enticed Isabella Potenam, a maiden, from the service of Thomas Harlowe, and carried her to their house in the parish of All Hallows Berkyng, and there shut and sealed her, and sold her to be debauched by George Galliman [Galleyman] and others, against her will and crying out.’30 In the early 1470s, a young woman named Ellen Butler was searching for a position as a domestic servant in London, when a certain Thomas Bowde approached her. Bowde was a shrewd confidence man who used Ellen’s desire for domestic employment as a pretext to lure her into his home in Southwark, in which he operated a brothel. When Ellen refused to cooperate, Thomas then brought charges against her accusing her of owing him an insurmountable debt. Although El-len claimed coercion, the court sided with Thomas, and Ellen faced the choice of imprisonment for delinquency or a return with Thomas to employment in his brothel. Evidently Ellen chose imprisonment, because at some point between 1473 and 1475 she petitioned the bishop of Winchester for a release from prison, although her fate is unknown.31 In 1490, Agnes Hutton stood accused of bawdry for allegedly procuring and soliciting, ‘young girls and the servants of divers men to commit the crime of fornication with divers men, and leads them to the chambers of Lombards, Spaniards, and Easterlings.’32 At the turn of the sixteenth century, the Commissary Court Act Books record that Robert Cliff and his wife were charged as common bawds for pimping their maidservant, Elizabeth Mountain, to ‘divers merchants,’ and also note that several years earlier, the couple had sold their previous maid, a young girl named Agnes Smith, to ‘Lombard merchants.’33 However, we do not know if this earlier sale was for a single encounter with young Agnes, or multiple encounters, or an outright permanent sale of a child between two parties. In 1517, as we have seen, John Barton abducted Joan Rawlins as she sought employment in domestic service in the city of London. A year later in 1518 in the Ward of Farringdon, Elizabeth Knyght, wife of John Knyght, was convicted of being ‘bawde to a certain person who committed the foul and detestable sin of lechery in her house with a young girl of thirteen years to the great displeasure of Almighty God.’ According to the proceedings, the victim testified that the wife of one Everard, a carpenter, had convinced the girl to go with Elizabeth Knyght, telling her that she would ‘have honest service [domestic service] and fair wage of said Elizabeth.’ The victim was escorted to the Knyghts’ house, and upon arrival she was sent upstairs to the bedchambers. Once inside, Elizabeth ‘shut fast the lower door, and there she [the victim] found the said man waiting, who took her in his arms, and as she cried, he stopped her mouth and had do with her against her will.’34

The Role of Violence in Late Medieval Sex Trafficking Networks

The late medieval sex industry retained and compelled labor through coercion, intimidation, brute force and outright rape. Yet the experience of violence in the late medieval sex trade was also, in part, the experience of violence in the urban environment, and the commercial sex industry was associated with other professions known to traffic in vice and brutishness.35 We may recall that Avignon in the 1240s banned gambling in brothels and the homes of prostitutes as well as in taverns and inns, and that Louis IX in 1256 banned his officers from visiting both taverns and brothels.

In London in September 1281, 29 men were arrested on charges of ‘divers trespasses, as for homicides, robberies, beatings, assaults […] with swords and bucklers.’ The charges also include gambling and ‘keeping houses of ill fame (lupanaria), contrary to the peace of the lord the King, and contrary to the ordinance and provision of good men of the City.’36 The 1393 municipal ordinance from London connected, ‘many and divers affrays, broils, and dissensions,’ as well as the murders of ‘many men’ with ‘the frequent resort of, and consorting with, common harlots, at taverns, brewhouses of huksters, and other places of ill-fame,’ within the city.37

As we have seen, taverns were frequently associated with the commercial sex industry because they often doubled as informal or illicit brothels, and as such they were also venues where sexual violence was commonplace. In London, for example, on 12 March 1301, Joice de Cornwall, a peleter, was stabbed to death following an incident in a tavern. Joice and his associate, a skinner known as Thomas of Bristol, were playing checkers at an inn run by a certain Alice de Wautham, when several men broke into the house carrying a woman with them. The men dropped the woman on the checker table, disrupting the game. Thomas took exception to the commotion, and words quickly escalated to a knife fight. Joice was stabbed in the chest and collapsed dead in the streets of Walebrok Ward.38

On 25 March 1325, the coroner’s roll reports that a tailor, Walter de Benygtone, met his end in a brawl at a ‘public house’ (mercatoria) owned by one Gilbert de Mordone in Bridge Ward. According to the official investigation, Walter de Benygtone and seventeen unnamed companions had come to the alehouse with ‘stones in their hoods, swords, knives and other weapons, and were there sitting and drinking four gallons of beer, lying in wait to seize and carry off Emma, daughter of the late Robert Pourte then under the charge of the said Gilbert.’ The wife of Gilbert de Mordone, Mabel, and the tavern staff asked Walter and his associates to leave the establishment, but the men replied that they would stay because the house was public, and they were spending money. Mabel then hurried young Emma upstairs to her chambers, angering Walter, and he in turn attacked the tavern staff. The fight spilled into the streets and when neighbors came to intervene, Walter attacked them and was subsequently killed in the brawl.39

In December of 1374, according to court proceedings,

John Loryng, William Neweman, Richard Bereford, William Stratford and Robert Buckston were indicted with others, not taken, for having been present with arms to give assistance to a certain John Spencer and others, who had gone with swords and bucklers and cuirasses, called ‘jakkes,’ under their outer garments to the inn of John Godard, hostiller, in the parish of St. Peter’s Cornhill, where they broke into a chamber occupied by Katherine de Brewes and carried her out, dragging her along the floor by her arms and clothes, naked upwards to the waist and with her hair hanging over her bosom, until the neighbours, aroused by the cries of her servants and herself, came and rescued her.40

The men subsequently pleaded not guilty and were acquitted of the charges.

Outside of confined spaces and in the open space of the streets, ‘respectable’ women were generally expected to avoid making eye contact in order to preserve a sense of privacy and personal space. Men, in contrast, held up their gaze to survey that public space and to thus dominate it, as well as to remain alert for potential intrusions into their personal space. Prostitution put women in an awkward position; like ‘respectable’ women, prostitutes were primarily concerned about personal space, and like men, prostitutes kept their gaze high in order to survey the public space, but unlike either of their ‘respectable’ counterparts, prostitutes invited the violation of their personal space.41

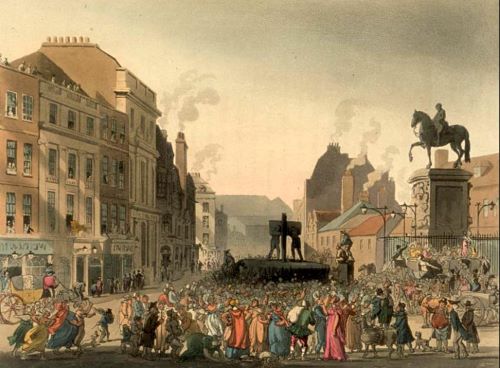

Such intrusion brought not only the promise of economic gain but also the risk of violence, and municipal and ecclesiastical authorities saw the invitation of the prostitute to violate personal space as a threat to the public order. They thus took steps to enclose sex workers in areas or establishments authorized for prostitution in order to contain that threat. Of course, not every prostitute was willing to go along with formal policies of segregation. When the women resisted official attempts to restrict their movement, municipalities responded by authorizing the use of force to compel their compliance, such as the official expulsion of prostitutes from ‘respectable’ neighborhoods throughout France over the course of the thirteenth century, which is documented in municipal and royal ordinances, or the early fourteenth-century municipal statute of Nîmes that authorized the beating of any ‘public woman’ found outside of the town’s red-light district. Throughout the second half of the fifteenth century in Dijon, with the permission of local authorities, the women of the municipal brothel repeatedly hunted down their competition (i.e. freelance prostitutes), and threatened to have them forcibly carried off into the brothel if they persisted in their activities.42 Thus the borders between reputable and disreputable neighborhoods were defined by, and reinforced through, state-sanctioned violence.

In England, a case from 1382 typifies official tolerance of violence against suspected prostitutes. On 9 July of that year, a certain chaplain named Thomas Norwich answered an official charge of trespassing by one Henry de Wilton. Henry claimed that Thomas had, ‘on divers occasions between 1 August 1381 and 8 July 1382, by force and arms and against the peace, had eloigned and carried away the plaintiff’s wife, Joan, [as well as] woollen and linen cloths, silver plate, dishes, pewter saltcellars, and iron and brass pots and pans.’ According to the court proceedings, ‘A jury brought in a verdict that as regards the wife, she was nothing but a common strumpet, and so there was no eloigning, but the defendant was in possession of certain goods belonging to the plaintiff of the value of 60s […] It was considered that the defendant pay 60s damages and restore the goods, in default of which he was committed to prison.’43 In this disturbing case, Thomas faced restitution and potential prison time, not for the abduction and likely sexual assault of Joan, but for the theft of moveable property. Since Joan was ‘nothing but a common strumpet,’ she could not have been assaulted according to the judgment of the court; whether Joan engaged in prostitution is unknown, although from the proceedings it is evident that her public persona was considered disreputable. Regardless of her activities, the court records illustrate the dangers faced by trafficking victims and sex workers in general. Their marginal social status meant susceptibility to officially tolerated, or officially authorized, violence in addition to the risks inherent in their trade.

Yet on occasion, authorities did act to protect sex workers from violence. In 1231 in Sicily, for example, Frederick II Hohenstaufen (1194–1250) in his Constitutions of Melfi decreed the death penalty for the rape of a prostitute.44 The 1285 authorization of the Montpellier red-light district promised the women that they would ‘now and forever remain under the protection of the lord king [James II of Majorca] and the council of this town.’ In 1383, the Bishop of Albi suggested that the city build two brothels: one outside the walls and another inside where the women could be housed at night for their safety and protection. Ordinances across the Languedoc imposed substantial fines and occasionally corporal punishment for the rape of a prostitute throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.45 In 1389 in Valence and Avignon, the rape of a prostitute in the municipal brothel carried a fine of 100 sous.46 Beginning in 1425 and for much of the fifteenth century, the municipal brothel of Toulouse was under the official protection of both the royal seneschal and the vicar of the city and guarded by troops responsible to the captain of the watch (capitan del geyt). The ‘abbess’ of the brothel, one Johannetta de Carneri, was present at the seneschal’s court for the formal proclamation of protection, and the Fleurdelisés was affixed to the house as a sign of royal patronage.47

In England, throughout the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries the municipal authorities of Southwark, Sandwich, and Southampton prohibited the managers of the stews and brothels from beating the women in their employ.48 In Southwark, brothel-keepers were also prohibited from loaning money to their prostitutes, presumably to ensure they did not trap the women in the brothel through debt, although this regulation was apparently either ignored or forgotten in the case of Ellen Butler.49 Thus in many cases, municipalities used violence to create a system of rewards and punishments that encouraged prostitutes to voluntarily cooperate in their own segregation. Inside designated zones of prostitution the women were officially protected from violence, but outside of those zones they were susceptible to officially authorized or tolerated violence.

Of course, we may ask who protected women from their ‘protectors,’ who could just as easily become their persecutors? In 1304, for example, the royal officers of Philip IV of France (r. 1285–1314) ejected and ‘disinhabited’ (deshabitées) prostitutes living on the street of La Laguquein Beaucaire, at the request of the local nobility, burghers, and the Franciscans.50 In Dijon, Avignon, and Lyon, sergeants in the service of local nobility administered the local bathhouses and also ran them as informal brothels.51 In the 1450s, a group of unemployed mercenaries in Burgundy, the Coquillards, took up residence in the municipal brothel of Dijon, and as the self-appointed ‘protectors’ of the women extorted services and large sums of coin from them.52 In 1456, a 26-year-old woman named Catherine caught the eyes of archers in service of the Duke Philippe ‘le Bon’ of Burgundy (r. 1419–1467). The archers had made it publicly known that they planned to carry her off to the Dijon brothel. Under the threat of rape, Catherine chose to go to the brothel voluntarily in order to avoid the humiliation of being led there publicly.53 Catherine was not noted as being a prostitute in the documents; nevertheless, her ‘respectable’ status did not protect her from the threat of rape outside of the brothel, nor did municipal protection of the brothel prevent the threat of rape therein.

Violence permeated the brothel itself.54 In England, brothels were routinely referred to as ‘disorderly houses’ in court proceedings that ‘harbored men of ill fame.’ In London, six prostitutes f led the city following a pair of murders in their establishment in 1261. Edward II closed the city’s brothels in 1310 because he suspected they were harboring criminals. According to his royal decree, ‘receivers’ in connection with those brothels were associated with sex trafficking, robberies, murders, and ‘other diverse transgressions’ in the city of London. In the ‘disorderly house’ of Ellen De Evesham in the Ward of Farringdon Without in 1338,

In Christmas week last after midnight certain foreigners from her [Ellen’s] house attacked a man, who was passing along the highway with a light, and after felling him with blows on the head and body, bound his arms and legs and carried him within the said Ellen’s house, and that she was present with a lighted candle in her hand during the assault.55

In 1391, the city of London issued yet another municipal ordinance prohibiting boatmen from transporting any ‘man or woman to the stewes between sunset and sunrise, nor moor his boat within 20 fathoms of the shore during that period, lest misdoers be assisted in their coming and going.’56 In the Ward of Crepulgate Without in December of 1422, the ward’s bathhouse was indicted ‘as a nuisance and trouble to neighbors, because it is a common house of harlotry and bawdry, and a great resort of thieves and also of priests and their concubines, to the great disgrace of the city and the danger and mischief of the neighbors and passersby.’57 In Southampton and Southwark, the Bawds of the Stewes were repeatedly fined for physically abusing their prostitutes despite municipal statutes and prohibitions.58 The fact that such f ines were repetitive indicates that violence within the stews was endemic and that legal remedies were quite simply ineffective.

In France, violence affected both sex workers and staff in municipal brothels. In August of 1448, Jehan Sudre worked as private security for the municipal brothel of Toulouse and was killed in the establishment during an altercation with a certain Poncelet Paulin. In 1460, a young man from Toulouse named Guillot del Cung faced royal prosecution for 24 offenses including the abduction of a young woman named Jahanete from the municipal brothel of Toulouse, and her sale across the Languedoc in Carcassonne, Narbonne, Beziers, Montpellier, Avignon, and Marseilles, to his considerable profit.59 In 1467 in Dijon, the lieutenant of the provost was sued for refusing to intervene in multiple assaults and brawls in the bathhouse of Marion la Liegeoise.60

Although the women, staff, and patrons of the establishments were vulnerable to violence, the brothel itself was often susceptible during times of unrest. A brothel owned by the Lord Mayor of London, William Walworth (d. 1385), was attacked in 1381 during the Peasants’ Revolt.61 In France, the brothels of Toulouse were attacked on 9 May 1357 when rioters protesting the raising of new taxes, ‘took […] weapons to attack Ghaste-Narbonnais, where Count [Jean] d’Armagnac, the king’s lieutenant in Languedoc, was making his residence. But after they were repulsed, they then turned their fury against the homes of the public girls […] ransacking everything, cutting fruit trees, throwing wine and food, and violating […] the royal safeguard.’62 In Burgundy, the Dijon brothel was sacked seven times in the 50 years between 1495 and 1545.63

In fact, the very foundation of the Dijon municipal brothel was precipitated by cruelty and brutishness. The establishment was founded in 1436 as a public rape epidemic scourged the city. Authorities in Dijon, as in many Western European cities, saw the founding of a red-light district or a municipal brothel as the solution to a greater evil, which was the threat of violence upon ‘respectable’ women and girls.64 The Dijon brothel was thus founded with the intention of providing an acceptable outlet for male aggression: prostitutes (i.e. poor women and girls). If the city fathers hoped that the founding of the municipal brothel would help curb the threats to civic order, they were mistaken. The brothel did little to quell the violence; over the next 50 years between 1436 and 1486 there were over 125 documented cases of public rape, a number likely representing a mere fraction of the total assaults committed. The violence continued in Dijon well into the sixteenth century, nearly a century after the brothel was founded. The acts themselves were accompanied by brutality that always included beatings and, in one case, dragging a pregnant woman through the snow-covered streets.65

Violence was a regular part of life for Kris in her Chicago pimp house. She had to ask permission for everything including eating, sleeping, showering, or using the toilet. The rules were enforced through beatings and threats thereof. However, the rules constantly changed without her knowledge, all in order to keep her off guard. As a result, she and the other girls formed close bonds of friendship as they experienced trauma, violence, and fear together. Yet, these bonds also became sources for further control. Her traffickers threatened to hurt or kill her friends if Kris ever tried to run away. If she left, they would pay the price of her escape.

Her traffickers’ threats of violence were not empty. Her pimp stabbed a rival gang member to death in front of her. As he wiped clean his bloody knife, he told her that he would kill her if she ever spoke about the murder to anyone. He expected loyalty and obedience; Kris obeyed and kept her mouth shut.

Anne tried to escape from the truck several times, and so her traf f icker kept her inside by tying her down to the bunk. He kept a loaded gun in the cabin and ensured her cooperation through physical violence and intimidation; Anne understood that he would shoot her if she tried to escape. ‘There was no getting out of the truck,’ she said simply. ‘Once I was in the truck, I wasn’t getting out.’ While on the road, he kept her on a tight leash. ‘Whatever he wanted, I did. If he wanted a sandwich, then I made him a sandwich. I was his servant; I was a slave in that truck.’

The Role of the Authorities in Sex Trafficking Networks

The participation of the authorities themselves in the commercial sex industry complicated matters further for trafficking victims. The rise of municipal brothels beginning in the latter half of the fourteenth century meant that municipalities and local officials now had vested interests in the commercial sex industry. By extending official protection from violence to prostitutes within authorized red-light districts or brothels, authorities sought not only the containment of sex work, but also the protection of those public and personal investments. Municipal involvement in commercial sex in turn produced a conflict of interest that went to the heart of human trafficking; that is, the very officials tasked with public safety also had personal stakes in an industry that involved sex trafficking.

In Southwark, the Bishop of Winchester had retained authority over the bathhouses in the borough as part of the Winchester Liberty since the early fourteenth century, and under his supervision and protection the commercial sex industry grew and thrived to his personal prof it. Despite ecclesiastical oversight, local and royal authorities were aware of trafficking victims in the Southwark baths. For example, the fourteenth-century Dyvers Ordinaunces and Constitutions is explicit in its preamble that, ‘to the gret displesuir of God and gret hurt unto the lorde King […] orrible synne has multiplied […] women are being kept in brothels against their will.’ The Ordinances went on to charge the royal bailiff with weekly inspections to ensure public health in the brothels, and to ensure that the women were not being beaten or held against their wishes.66 Direct royal intervention apparently relieved the bishop of his responsibilities as a landed magnate to manage the safety of the stews, because extant records suggest that only by the beginning of the sixteenth century had the episcopal see also begun to send officers into the baths to inquire if women were being held against their will.67

The Lord Mayor of London was not the only municipal official to own a brothel in Southwark; wealthy Londoners, including members of the Aldermen Council, were so deeply invested in the commercial sex industry that municipal authorities declared in 1417 that, ‘No Alderman, Commoner, or other person whatsoever shall thenceforth receive as a tenant any man or woman known to be living a vicious life.’68 In 1518, in the parish of Thornton, under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Lincoln, parishioners informed the bishop’s officers that the rector, a Lord Thomas Rogers, lived ‘intemperately’ (incontinenter) with a certain woman named Joan Thakham, who stood accused of being a common prostitute and of having kept a common tavern in the parish rectory.69

In France, prelates, local lords, and municipal officials all participated in the commercial sex industry. For example, the Bishop of Albi claimed as one of his rights the authority to administer and to regulate prostitution in the town, including the location of the municipal brothel.70 The deputy magistrates of both Tarascon and Beaucaire openly used their positions to pimp, as formal complaints throughout the middle of the fifteenth century attest.71 Francis de Genas, a royal courtier who also held the position of ‘Général des finances’ in Languedoc, owned a brothel in Valence during the 1450s and kept annual accounts of his profits from the establishment. The bathhouses of Langres belonged to the bishop, and the abbey of Saint-Étienne owned the baths of Saint-Michel in Dijon. The provost of Dijon, a nobleman named J. de Marnay, used his aristocratic position to abduct and sell women into prostitution rings and bathhouses throughout the city, as well as into the municipal brothel. The local procuresses who managed many of these operations were also close personal associates of the provost.72

Jeanne Saignant, considered the finest maquerelle in Dijon during the 1460s, enjoyed the protection of both ecclesiastical and secular authorities. For two decades, her bathhouse at Saint-Philibert boasted ‘the finest flesh,’ and catered to single and married men, clerics, and the local nobility. Her girls, meanwhile, were heavily indebted to Madame Saignant, who used their debt to trap them in the baths. Jeanne herself ran in exclusive circles. She kept company with local noblewomen and was a close friend of Jean Coustain, the valet de chambre of Duke Philippe ‘le Bon’. Her brother was a priest, allowing her to cater to the clergy and to thus enjoy the unspoken protection of local ecclesiastical authorities. Through her personal and professional networks of associates and clients, Saignant was able to delay for years legal actions taken against her on charges of blackmail and procuring. When she was finally brought before the courts, her trial lasted an impressive four years.73

Today, official corruption remains an obstacle in the global fight against human trafficking. Kris experienced that corruption personally; a Chicago police officer owned the building that served as Kris’s pimp house. She was introduced to him on the day that she arrived at the house, her first day in the city. Her traffickers made it clear that the officer was aware of the drugs, prostitution, and violence that went on inside his building. Moreover, they claimed that many officers in the city’s police department cooperated with them; thus, she believed that if she went to the authorities, her traffickers would know and would punish her accordingly.

The officer would visit regularly, drink beer with her pimp, and have sex with the girls. After her pimp murdered his rival in front of her, the officer who owned the building ‘investigated’ the murder. Her pimp was never prosecuted.

The Clients of the Late Medieval Commercial Sex Industry

Human trafficking is fundamentally an exchange, and as such demand underpins every aspect of its activity. Simply put, without clients there is no commercial sex industry. Like traffickers, clients spanned the gamut; single and married men, foreign merchants, and clergy are all represented in the sources. In general, the legal client base of the commercial sex industry evolved over the centuries. In the late thirteenth century and well into the fourteenth century, the municipal ordinances that established red-light districts generally did not mention the social status of clients, or in some cases they explicitly protected men from charges of adultery so long as they visited prostitutes within designated areas. As time went on, however, social mores regarding sexual conduct gradually became less permissive for married men and for members of the clergy, and these men were increasingly both barred from brothels and prosecuted for adultery. For the commercial sex industry, single laymen remained its largest and most reliable customer demographic.

Generally, brothels and prostitution rings catered to day laborers, craftsmen, sailors and merchants, as well as members of nobility or their households. The day laborers, craftsmen, and sailors tended to be poor young men who often had few prospects for marriage in an urban environment where they were in competition with their wealthier peers and with older, established widowers. Poor single men often targeted women in the households of their wealthier rivals, and their bitterness and their sense of entitlement are palpable in extant court proceedings. For example, in Dijon in 1449, G. Robelin, a journeyman in the butcher’s trade, shouted to a young domestic servant that he would have his pleasure with her just like her master.74 In 1454, a gang of six young men assaulted the domestic servant of a certain Mongin, an unmarried carpenter, in the streets of the city.75 In 1505, the sixteen-year old niece of the viscount-mayor of the city was accosted in the streets by two journeymen masons who shouted, ‘We are going to fuck you; we can fuck you just as well as the others!’ In 1535, the son of a local weaver threatened a 22-year-old domestic servant named Jaquette that he had ‘a right to have a go with you just like the others.’76

Overall, the matter of married men visiting prostitutes followed a trend from tolerance in the late thirteenth century to intolerance by the middle of the fifteenth century. While late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century decrees establishing red-light districts sometimes included clauses that protected men from charges of adultery within designated areas for prostitution, by the middle of the fifteenth century those protective clauses disappeared, while statutes that barred married men from brothels began to appear.

In France, for example, the Synod of Avignon of 1441 barred married men from the municipal brothel.77 In 1448, married men who kept concubines were fined 50 livres touronensis in Barbentane.78 In 1445, the royal grant to Castelnaudary for the establishment of a public brothel specified the large number of unmarried men in the town as a major justification for the royal license. Sexual misconduct among married men in the town remained a concern for the Crown because in 1510, a royal letter to the judge of Castelnaudary urged the punishment of both married men who kept concubines and the women themselves. As a result, the men were threatened with prison and a fine, while the women faced the whip and banishment from Castelnaudary. In Lyon, when residents filed complaints against a bathhouse owned by the lawyer for the archbishop, the lawyer argued that the brothel was upstanding since it admitted no married men. In 1501, a married man in Pamiers was charged with adultery after he was found in the company of two prostitutes.79 In Dijon, Jeanne Saignant specifically catered to married men in her bathhouse because, as she claimed in her court deposition, they were willing to pay more than poor single men.80 In 1487, municipal regulations in Aubignan and Loriol in the territories of the Comte Venaissin forbade prostitutes from committing adultery with married men.81

In England, as in France, licensed brothels admitted unmarried young men who were perceived as threats to the wives and daughters of ‘respectable’ burghers. Many towns prohibited the admission of married men into brothels, although the effectiveness of these regulations is questionable.82 In Southwark, for example, brothel-keepers were forbidden from residing with any woman except their wives. Women who violated this prohibition were to be turned over to the bishop’s off icers by the brothel-keeper, under penalty of a 40-shilling fine. The women then faced a 20-shilling fine and the cucking stool.83 These provisions ensured that married men did not commit adultery and that public prostitutes did not become paramours of their employers.

Foreign merchants represented another important client base for the commercial sex industry. Merchants carried coin with them; they were often away from their wives and families for extended periods of time and could easily claim unmarried status, and they had business connections in port towns that could include disreputable figures. In most cases, these merchants appear as end clients rather than middlemen, but not always. Recall that Margaret Hathewyk prostituted Isabel Lane among Lombard merchants, during which times Isabel ‘was def lowered against her will’; Peter Manyfeld sold Alice Burley to Germans in the London Steelyard, and Robert Cliff and his wife were charged as common bawds for pimping their maidservant, Elizabeth Mountain, ‘to divers merchants.’ In 1438, Agnes Talbot was charged with pimping ‘a certain Joan to the Flemings and Lombards.’84 In 1490, Agnes Hutton stood accused of procuring ‘young girls and the servants of divers men […] and lead[ing] them to the chambers of Lombards, Spaniards, and Easterlings.’ Richard Wyer in 1529 was convicted of bawdry for being ‘a common bringer and conveyer of single women to merchant strangers’ places […] to use and occupy in the foul sins of lechery to the great displeasure of Almighty God.’85 Joan Chapman acted as a bawd between her fifteen-year-old daughter Alice and German and Flemish merchants and sailors in Sandwich.

The clergy is well represented as a client demographic for the commercial sex industry in court records, because ecclesiastics, like merchants, generally had greater access to coin than poor single laborers. In England, we have already seen how, in 1385, Elizabeth Moryng encouraged her apprentices in her embroidery shop ‘to live in lechery and to go with friars, chaplains, and all others wishing to have them.’ In 1395, John Rykener testified in court that ‘many priests had committed that crime with him as with a woman, how many he did not know, and he said that he took priests more readily than others because they wished to give him more than other people.’86 Ruth Mazo Karras reasons that female prostitutes presumably had similar expectations of the clergy.87 The bathhouse in the Ward of Crepulgate Without was regarded ‘as a nuisance and trouble to neighbors, because it is a common house of harlotry and bawdry, and a great resort […] of priests and their concubines, to the great disgrace of the city.’ In 1471, Alice Sholton, ‘bawd to priests’ (pronuba sacerdotibus), stood accused of trafficking ‘a certain woman’ (quidam mulier) to a priest, despite the victim’s protests and resistance.88 In 1516, Elizabeth Chebyn was convicted of being a ‘common harlot and a strumpet,’ who had the audacity to walk the streets of London dressed as a priest, a biting critique of the clergy of her day. Elizabeth knew from personal experience the importance of clerics to the commercial sex industry: when she was arrested, she was in bed between two priests.89

In Dijon, Rossiaud has estimated that clerics accounted for roughly 20 percent of the regular clientele of the city’s brothels and bathhouses.90 Members of the clergy were implicated either directly or indirectly in brawls,91 trafficking,92 and several cases of public rape in the city streets, municipal baths, and brothels.93 For 20 years, Jeanne Saignant catered to ecclesiastics in Dijon. In Avignon in 1441, the Synod of Avignon addressed clerical sexual misconduct directly and banned members of the clergy from the municipal brothel.94 In 1494, the town of Beaucaire decreed that clerics who were caught with prostitutes and other shameful women (mulieres inhonestas) were to be brought to the attention of the archbishop and the vicar of Arles.95

In England, as in France, the prosecution of clerics and prostitutes varied widely at the local level. In some towns, such as in Gloucester, municipal authorities sought to punish any cleric found in the company of ‘whores, strumpets, or men’s wives’ after nightfall.96 In Letter Book I (1400–1422), Reginald Sharpe, the editor of the Letter Books of the Corporation of London Record Office, introduces a section of ten folios (286r–290r) covering sexual offenses by observing that the majority of men cited for adultery with prostitutes, unmarried girls, and married women were chantry priests.97

Yet even if municipal authorities took special notice of clerical misconduct, society remained largely ambivalent on the issue. On the one hand, the clergy scandalized the public when they were charged with keeping concubines, or hiring the services of bawds to obtain sexual partners, or attracting the attentions of unwed girls and married women.98 On the other hand, for much of the Middle Ages, celibacy was an ideal for clerics, and society did not expect such men to possess heroic virtue or self-control. Socially, it was preferable to have a member of the clergy visit the brothel than to have him flirt with married women or their daughters. Thus, most charges involving clerical sexual misconduct involve procuration, concubinage, or suspicious activity with the wives and daughters of upstanding local citizens.

Although during the fifteenth century the ecclesiastical hierarchy resisted reform efforts in support of clerical marriage, and insisted instead upon celibacy and chastity, Church officials nevertheless appear to have accepted the fact that many of its members would fail to live up to their vows of chastity, since they begrudgingly tolerated clerical visits to public brothels. Society might have ridiculed the licentiousness of monks and priests, but they did not outright condemn it.99

The Reformation and the End of the Institutional Brothel

For much of the late Middle Ages, the developmental process of the commercial sex industry had been one of acceptance, legitimation, and growth. However, as the fifteenth century gave way to the sixteenth, many of the sex industry’s gains in terms of social integration, protection, and regulation were reversed in the wake of the religious reform movements that swept across Europe. Initially, the concerns of reformers regarding sexual misconduct were part of broader anticlerical critiques. In the eyes of the reformers, the civic-minded married household was a concrete example of piety and morality set in stark relief against the licentiousness of monks and priests.

Many reformers addressed the role of women in society: they revitalized the roles of wife and mother, and they encouraged women’s education in order to read the Bible and to participate in religious services. Yet at the same time, reformers limited the social role of wives to the home and emphasized their subordination to their husbands. For evangelical leaders, however, their status as married men indicated their inclusion in the municipality as citizens, which meant that for women, marriage meant exclusion from civic life, but for men, marriage meant inclusion.100 Married, faithful, and subject to the same standards of morality as the rest of the laity, evangelical leaders presented themselves as paragons of moral and civic virtue, as opposed to unmarried priests whose opulence and licentiousness were held up as examples of corruption and hypocrisy. The lecherous monk, a stock character in evangelical polemics, was guilty of every kind of sexual sin, but he was not alone in his perversity.101 Women were now considered willing participants in their own corruption to the scandal and humiliation of their social superiors: their husbands and fathers.102

In the beginning of the Reformation, attacks on prostitution thus came as part of broader attacks against the clergy. Allegations of clerical licentious-ness in frequenting brothels, seducing married women and virgins, and keeping concubines made no distinctions among the social status of the women in question. To reformers, sexual misconduct among clerics was simply ‘whoring,’ regardless of whether the woman was a prostitute, wife, or virgin. It was a small step from attacking clerics to attacking the women in their company, especially prostitutes who were subsequently classed with priests and monks. Like the priest or monk who led virgins and married women astray in their unbridled lust, the image of the prostitute evolved into a malignant temptress; vain, selfish, and given to opulence, they led upstanding married men astray and threatened the souls of their clients and the moral and civic order of a reformed society.103 They were not merely the companions of priests and monks, and thus guilty by association; they were now guilty in their own right, symbols of the decadence and corruption that threatened to engulf the world as epitomized by the richly attired Whore of Babylon astride the seven-headed Beast adorning the Lutheran Bible.

During the Reformation, the logic of prostitution was turned on its head. The commercial sex industry had for much of the late Middle Ages been considered a social safety valve. Men’s lust was considered natural, but also dangerous and socially disruptive if left to boil over. Prostitution was then deemed an appropriate outlet to channel male aggression and licentious-ness. By the second quarter of the sixteenth century, control over desire became a defining feature of reformed masculinity, and now prostitutes were likened to adulteresses as sources of dangerous and socially disruptive lust. Prostitution had become a moral offense instead of a trade, and ‘prostitute’ had become a moral category instead of a profession. As such, the distinctions among prostitution, adultery, and fornication blurred.104

Men were also now culpable in the acts of adultery and fornication, and they were also now considered sinners. The prosecution of married men who visited brothels, which had already begun in the middle of the f ifteenth century, became commonplace in the sixteenth century. Bachelors who visited married prostitutes were found guilty of adultery because the women were married. Clients now faced heavy fines and imprisonment for patronizing prostitutes and brothels. Yet, as Lyndal Roper notes, women still faced more severe penalties. Men, and especially men of status, could more readily convert imprisonment into cash f ines, when they were prosecuted at all, and their trysts were considered aberrations and lapses in judgment rather than indications of corruption and debauchery. For women, banishment, imprisonment, and corporal punishment could not be so easily commuted, and charges of prostitution suggested deeper underlying corruption.105

The attacks on prostitutes naturally led to attacks on brothels. As early as 1520, Martin Luther (1483–1546) addressed the presence of brothels in cities and larger towns across the Holy Roman Empire:

Finally, is it not lamentable that we Christians tolerate open and common brothels in our midst, when all of us are baptized unto chastity? I know perfectly well what some will say to this, that is, that it is not a custom peculiar to one nation, that it would be difficult to put a stop to it, and moreover, that it is better to keep such a house than that married women, or girls, or others of still more honorable estate should be outraged. Nevertheless, should not the government, which is temporal and also Christian, realize that such evil cannot be prevented by that kind of heathenish practice? If the children of Israel could exist without such abomination, why cannot Christians do as much? In fact, how do so many cities, country towns, market towns, and villages do without such houses? Why cannot large cities do without them as well?106

Luther acknowledged the time-honored argument that brothels prevented a worse evil, the violation of respectable women and girls, by providing an outlet for male aggression and licentiousness; he then rejected such reasoning and argued instead that male lust was in fact controllable, and that cities and towns could do without such public houses. As the old arguments justifying the existence of brothels were dismantled, reformers seized the moral high ground and began to shutter municipal brothels across Western and Central Europe. Augsburg closed its brothel in 1532; Ulm in 1537; Regensburg in 1553; Nuremburg in 1562. In England, Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) ordered the closure of all Southwark brothels, regardless of their licensing, in 1546.107

In France, where Reformation efforts were largely underground, municipalities continued to make major investments in their municipal brothels throughout the first half of the sixteenth century, but the tide was turning against the commercial sex industry because both reformers and counter-reformers were now marked by open hostility towards prostitution. The Languedoc proved fertile ground for French reformers, but even counter-reformers such as the Jesuits zealously opposed institutionalized prostitution in their bid to strengthen clerical discipline. Francis I closed the brothels of Glatigny in Paris in 1518, but the locals, ‘fearing that the King might be induced to change his edict before it was executed,’ took up arms and tools and destroyed all of the brothels in the area within a day.108 Alès closed its brothel in 1553; Castelnaudary in 1555; Montpellier and Toulouse in 1557. The era of the medieval institutionalized brothel had come to an end, and the future of prostitution would become one of criminality and marginality.

The study of late medieval sex trafficking makes clear that poverty and limited economic opportunities for women led to vulnerability, and thus to victimization, as women struggled to alleviate their insecurity within the narrow employment options available to them. Traffickers, noble and common, male and female, understood these constraints and skillfully exploited them in order to funnel victims into the late medieval commercial sex industry, oftentimes with the acquiescence or participation of local authorities. Once in, it was diff icult to get out. Violence compelled victims to labor for an industry whose profits filled the coffers of both the municipalities and the local elite.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 5 (215-245) from Human Trafficking in Medieval Europe: Slavery, Sexual Exploitation, and Prostitution, by Christopher Paolella (Amsterdam University Press, 10.05.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.