Introduction

From the start of European expansion into the Atlantic world, Britain fought other powers for territory in the Caribbean and many islands became part of the British Empire. The region experienced near eradication and expulsion of its indigenous populations by European powers. It was also on the receiving end of the largest enforced migration ever witnessed: the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Slavery and its resistance by enslaved Africans was an integral part of Caribbean history. In a remarkably short period of time and in the face of such extraordinary conditions, new cultures and identities were formed in the Caribbean.

This exhibition is based on Colonial Office documents held at The National Archives — home to records belonging to the British Government. The documents we have used in this exhibition are correspondence from administrators of local governments in the British West Indies, and date from 1692-1921. While the documents give an interesting insight into Caribbean history, they also show the views of local people, particularly those concerned with trade and in governance. Those in power were mainly of a particular class, social standing or political allegiance, and the documents reflect this bias. However, there are stories of a more diverse nature, and the Colonial Office archive does include voices from different parts of society, including indigenous and enslaved peoples, through to women and the poor.

Movement of People

The Caribbean is composed of people from all over the world including those taken there by force and those who migrated freely.

Caribs lived in the Caribbean for thousands of years. There were many communities of people we now know as Caribs, including Galibi and various Arawakan speakers such as the Kalinago. Beginning in the 16th century, many were killed or expelled from the islands by European forces. They asserted their identity by fighting for land and political rights. One example is Brigands’ War, also known as the Second Carib War (1794 -1798).

Merchants and plantation owners moved into the region. Indentured servants, political dissidents and others from the British Isles provided the first plantation labour.

The biggest migration to the Caribbean was a forced migration of enslaved people from Africa through the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Many of the merchants who settled in the Caribbean during the 17th and 18th centuries were involved in slave trading. The early Caribbean was also a centre for piracy.

In the late 18th century, Britain moved soldiers and sailors to the Caribbean to defend against invasion by competing European powers and guard against anti-slavery revolutions and protests. Former enslaved people came from Canada to join the West India Regiment.

Indentured labour from India and China started in the 19th century. They migrated to the Caribbean to work on plantations in places such as Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana. So-called ‘Liberated Africans’ were also indentured during this time.

Many people also migrated from the Caribbean and people convicted of crimes were sometimes transported to Australia and England. Also, Bermuda had a convict establishment for British (including Irish) convicts.

Caribbean Identities

There were many different religious and cultural identities in the early Caribbean. Like much of the region, Port Royal in 17th century Jamaica was home to people of many different cultures and religions. Protestants, Catholics, Quakers and Jews had places of worship there.

Enslaved Africans constantly fought to keep their identity and heritage alive. They mixed African with European and indigenous traditions in carnival, religion, storytelling, Obeah and medicine.

One way in which Africans rebelled against slavery was by escaping and developing independent maroon communities. One such community that still exists today is Accompong Town in Jamaica.

Black Caribs and Yellow Caribs had communities in St. Vincent. Sometimes Caribs and former enslaved people worked together against colonial authorities.

Often people who were descended from slave owners and enslaved people were described as ‘coloured’ or ‘mulatto’. They could be freed if the slave owner chose although this did not always happen. A ‘free person of colour,’ who was accepted by the colonial authorities in 1790s Grenada and rose to a position of military and political power was Louis La Grenade.

There were many different religions in the Caribbean trying to establish themselves. In both Grenada and St. Lucia (former French islands) most people, especially those of African descent, were Catholics. In a society dominated by the established Anglican Church, followers of other denominations and religions struggled for religious and educational rights.

Women on different islands wrote letters and petitions: many fought for property and business rights, widows asked for financial help, others petitioned on behalf of male relatives, and some pushed for social and political change.

Slavery and Negotiating Freedom

Between 1662 and 1807 Britain shipped 3.1 million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Africans were forcibly brought to British owned colonies in the Caribbean and sold as slaves to work on plantations. Those engaged in the trade were driven by the huge financial gain to be made, both in the Caribbean and at home in Britain.

Enslaved people constantly rebelled against slavery right up until emancipation in 1834. Most spectacular were the slave revolts during the 18th and 19th centuries, including: Tacky’s rebellion in 1760s Jamaica, the Haitian Revolution (1789), Fedon’s 1790s revolution in Grenada, the 1816 Barbados slave revolt led by Bussa, and the major 1831 slave revolt in Jamaica led by Sam Sharpe. Also voices of dissent began emerging in Britain, highlighting the poor conditions of enslaved people. Whilst the Abolition movement was growing, so was the opposition by those with financial interests in the Caribbean.

The British slave trade officially ended in 1807, making the buying and selling of slaves from Africa illegal; however, slavery itself had not ended. It was not until 1 August 1834 that slavery ended in the British Caribbean following legislation passed the previous year. This was followed by a period of apprenticeship with freedom coming in 1838.

Even after the end of slavery and apprenticeship the Caribbean was not totally free. Former enslaved people received no compensation and had limited representation in the legislatures. Indentured labour from India and China was introduced after slavery. This system resulted in much abuse and was not abolished until the early part of the 20th century. After indenture, Indians and Africans struggled to own land and create their own communities.

Society and Welfare after Slavery

Following emancipation, there was a new society of freed people across the Caribbean: what did they do and what provisions were made for them?

During slavery, plantation owners decided what kind of shelter and medical care was given to their slaves. After the abolition of slavery most available work was on the very same plantations that former enslaved people had worked on; the wages were low, and people had inadequate rights to land. Rent and taxes were high, as was unemployment. The Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica was one example of the working classes protesting about such conditions.

From the middle to late 1800s, the Caribbean saw many changes. Colonial governments reformed judicial systems, police forces, education and health care. They built roads and railways, developed botanical gardens, improved water supplies and sanitation, and established cable communication. Authorities introduced mass vaccinations against common diseases, and provided relief following natural disasters.

Throughout the Caribbean, mental health institutions often suffered from poor standards of care, over crowding and patient neglect. By the 1870s many islands were constructing new facilities and attempting to improve patient care.

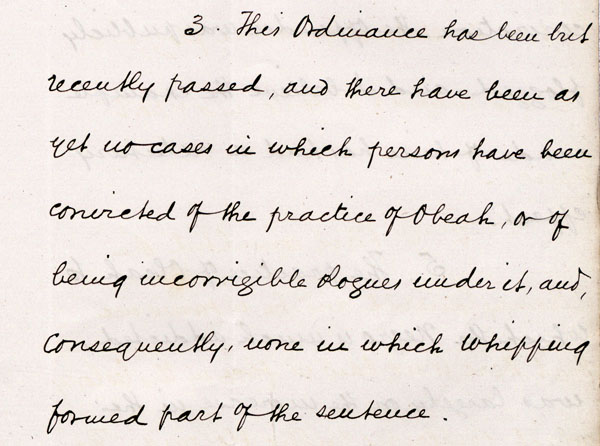

Despite reform, abuse of the system continued. For example, forced labour and flogging were still prevalent in prisons. Such punishments were now conducted by the state instead of slave owners. In 1870s St. Lucia, a man was publicly flogged in the market place for practising Obeah.

The schooling system established during slavery was expanded to teach Christian morals to the recently freed slaves. Later, academic and agricultural schools were instituted by the state. The Mico Charity was an important educational trust that established schools in the British Caribbean.

Caribbean and the Wider World

The Caribbean was a centre of trade for the various Carib peoples who lived throughout the region. After the arrival of the Europeans and the establishment of the plantation system, trade remained a core part of the region’s identity. The main exports from the Caribbean of sugar, molasses and rum were all made possible due to the fields of sugar cane worked by enslaved labour. Other important goods that came from the region included salt, rice, cocoa and fruit.

Because of the wealth to be gained, there were several land disputes between the various European powers. Some islands changed hands frequently in short periods of time.

Events happening on neighbouring islands and in the wider world, also greatly affected those in the British Caribbean. In the 18th century both the Haitian and American Revolutions caused people to migrate to various British Caribbean islands and affected trade. Additionally, the Haitian Revolution caused concern over regard to copycat revolts, especially in nearby Jamaica.

Throughout the 19th century the Caribbean had a tense relationship with the American South. For example, during the American Civil War Britain was neutral, refusing to allow thousands of free blacks from the south to move to Grenada despite the wishes of local plantation owners.

Workers from British Caribbean islands also moved to neighbouring Spanish islands and Central America in search of work. One of the main projects that attracted such workers was the building of the Panama Canal. Additionally, about 40,000 Jamaicans and Barbadians settled in Cuba in the early 20th century after migrating there to work in the sugar industry.

20th-Century Transitions

The late 19th century brought improvements in communications by telegraph cables and travel via steam ships. These many advances helped to make tourism a defining element of Caribbean life, with Americans and Canadians visiting the islands to escape the long northern winters.

During the First World War, Caribbean people travelled abroad to serve with British armed forces alongside other members of the Empire. Initially, West Indians volunteered, but were rejected by the British authorities. As the war progressed, the volunteers were accepted but were often given menial jobs and were posted to battles outside Europe. The various islands also gave money and local products for the war effort. Also, some islands maintained prisoner of war camps in which German civilians and sailors were held.

Political and labour changes swept through the islands in the form of Pan-Africanism, nationalism, Garveyism, and unionisation. From Jamaica to Trinidad black intellectuals and everyday people challenged local social and political establishments by fighting for changes in their constitutions and the right to vote.

It was also a time of massive reform of towns and government institutions. Businessmen, smugglers and merchants alike took advantage of the economic opportunities open to them. Cartels existed on some islands, and Bahamas was used by Americans to consume and buy alcohol during Prohibition.

The Caribbean is home to both a rich heritage and diverse mix of people. It is a centre of modern migration, resulting in a large diaspora in America, Britain, and Canada.

Bibliography

- Alan H. Adamson, Sugar without slaves: The political economy of British Guiana, 1838-1904 (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972)

- Jorma Ahvenainen, The History of the Caribbean Telegraphs before the First World War (Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1996)

- Juanita De Barros, Order and Place in a Colonial City: Patterns of Struggle and Resistance in Georgetown, British Guiana, 1889-1924 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003)

- C. Bayly, Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World, 1780-1830 (Harlow: Longman, 1989)

- Hilary Beckles, ‘Kalinago (Carib) Resistance to European Colonization of the Caribbean’ in Alan Cobley, ed., Crossroads of Empire: The European-Caribbean Connection, 1492-1992 (Cave Hill: University of the West Indies, Department of History, 1994), pp. 23-37.

- Hilary Beckles, A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Settlement to Nation-State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990)

- Virginia Bernhard, Slaves and Slaveholders in Bermuda, 1616-1782 (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1999)

- Clinton V. Black, History of Jamaica (London: Longman, 2002)

- Bridget Brereton, Race Relations in Colonial Trinidad, 1870-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979)

- Bridget Brereton, A History of Modern Trinidad, 1783-1962 (Kingston and London: Heinemann, 1981)

- Mavis C. Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal (Massachusetts: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc., 1988)

- Selwyn H. H. Carrington, The British West Indies During the American Revolution (Dordrecht and Providence: Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology/Foris Publications, 1988)

- Michael L. Conniff, Black Labor on a White Canal: Panama, 1904-1981 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985)

- Michael Craton, Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982)

- Michael Craton, Founded upon the Seas: a History of the Cayman Islands and Their People (Kingston and Miami: Ian Randle Publishers, 2003)

- Malcolm Cross and Gad Heuman, Labour in the Caribbean (London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1988)

- Selwyn R. Cudjoe, Beyond Boundaries: the Intellectual Tradition of Trinidad and Tobago in the Nineteenth Century (Wellesley, Massachusetts: Calaloux Publications, 2003)

- Vere T. Daly, The Making of Guyana (London: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1974)

- Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (London, 1789, reprinted by Longmans 1988 and others)

- David P. Geggus, ed., The impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic world (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina, 2001)

- Harry Goulbourne, Caribbean Transnational Experience (London: Pluto, 2002)

- Guy Grannum, Tracing Your West Indian Ancestors (London: Public Record Office, 2002)

- Catherine Hall, Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830-1867 (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002)

- Douglas Hamilton, Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic world, 1750-1820 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005)

- Edward Cecil Harris, Bermuda Forts, 1612-1957 (Bermuda: Bermuda Maritime Museum Press, 1997)

- Richard Hart, Slaves Who Abolished Slavery: Blacks in Rebellion (Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 1985, 2002)

- Douglas Hay and Paul Craven, ed., Masters, Servants, and Magistrates in Britain and the Empire, 1562-1955 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2004)

- Gad Heuman, ‘The Killing Time’: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1994)

- B. W. Higman, ed., Trade, Government and Society in Caribbean History, 1700-1920 (Kingston: Heinemann Educational Publishers, 1983)

- Lennox Honychurch, The Dominica Story: A History of the Island (London: Macmillan, rev.1995)

- Lennox Honychurch, ‘Chatoyer’s Artist: Agostino Brunias and the depiction of St Vincent’, © Lennox Honychurch, 2003, http://www.uwichill.edu.bb/bnccde/svg/conference/papers/ honychurch.html

[accessed 19 July 2006] - Glenford Howe, Race, War and Nationalism: A Social History of West Indians in the First World War (Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, and Oxford: James Currey Publishers, 2002)

- Vincent K. Hubbard, A History of St Kitts (Oxford: Macmillan, 2002)

- Curtis Jacobs, ‘The Fédons of Grenada, 1763-1814’, © Curtis Jacobs, 2002, http://www.cavehill.uwi.edu/bnccde/grenada/conference/papers/ Jacobsc.html

[accessed 19 July 2006] - Curtis Jacobs, ‘The Brigands’s War in St Vincent: The view from the French records, 1794-1796’, © Curtis Jacobs, 2003, http://www.cavehill.uwi.edu/bnccde/svg/conference/papers/ jacobs.html

[accessed 19 July 2006] - Winston James and Clive Harris, eds., Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain (London: Verso, 1993)

- Howard Johnson, The Bahamas from slavery to servitude, 1783-1933 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996)

- Madhavi Kale, Fragments of Empire: Capital, Slavery, and Indian Indentured Labor Migration in the British Caribbean (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998)

- Walton Look Lai, Indentured Labor, Caribbean Sugar (John Hopkins University Press, 1993)

- Geraldine Lane, Tracing Ancestors in Barbados: A Practical Guide (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2006)

- Frank McGlynn and S. Drescher, eds., The Meaning of Freedom: Economics, Politics, and Culture After Slavery (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992)

- J. R. Oldfield, Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilisation of Public Opinion against the Slave Trade, 1787-1807 (Frank Cass, 1998)

- Cyril Packwood, Chained on the Rock (Bermuda: The Island Press Limited, 1975)

- Diana Paton, No Bond But The Law: Punishment, Race and Gender in Jamaican State Formation, 1780-1870 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004)

- Elizabeth McLean Petras, Jamaican Labor Migration: White Capital and Black Labor, 1850-1930 (London: Westview Press, 1988)

- Bonham C. Richardson, Panama Money in Barbados, 1900-1920 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985)

- Lomarsh Roopnarine, ‘Indo-Caribbean Migration: From Periphery to Core’, Caribbean Quarterly, 49:3 (September 2003)

- Gail Saunders, Bahamian society after emancipation (Kingston: Ian Randle, 2003)

- Mimi Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean: from Arawaks to Zombies (London: Routledge, 2003)

- Beverley Steele, Grenada: A History of its People (Oxford: Macmillan, 2003)

- Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870 (London: Papermac, 1998)

- P. A. B. Thomson, Belize: A Concise History (Oxford: Macmillan, 2004)

- Mary Turner, Slaves and Missionaries: The Disintegration of Jamaican Slave Society, 1787-1834 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982)

- James Walvin, Black Ivory: A History of British Slavery, 2nd ed. (Oxford and Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 2001)

- Irma Watkins-Owens, Blood Relations: Caribbean Immigrants and the Harlem Community, 1900-1930 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996)

- Henry Campbell Wilkinson, Bermuda from Sail to Steam : The History of the Island from 1784 to 1901 (London: Oxford University Press, 1973)

- James Williams, ‘A Narrative of Events Since the First of August 1834 by James Williams, An Apprenticed Labourer in Jamaica’, © University of North Carolina http://docsouth.unc.edu/williamsjames/williams.html

[accessed 26 October 2006] - General History of the Caribbean volumes I-VI (London: UNESCO Publishing, 1999)

Originally published by The UK National Archives under Crown CopyrightOpen Government Licensing.