Slavery and the Roots of Racism

By Lance Selfa

Over 150 years ago, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrendered to the Union Army’s Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, ending the American Civil War.

Earlier that day, Lee had tried to fight his way out of a cordon of Union forces, in which the Northern forces–including several regiments of the all-Black U.S. Colored Troops–outnumbered his army six to one. Seeing the futility of carrying on the war, Lee decided to sue for peace.

Thus ended the Civil War, and with it, the war’s true cause: slavery. Writing from Britain in November 1861, near the beginning of the war, Karl Marx foresaw this. Against those who tried to excuse the South’s claims that it was merely defending itself against “Northern aggression,” Marx wrote: “The war of the Southern Confederacy is…not a war of defense, but a war of conquest, a war of conquest for the extension and perpetuation of slavery.”

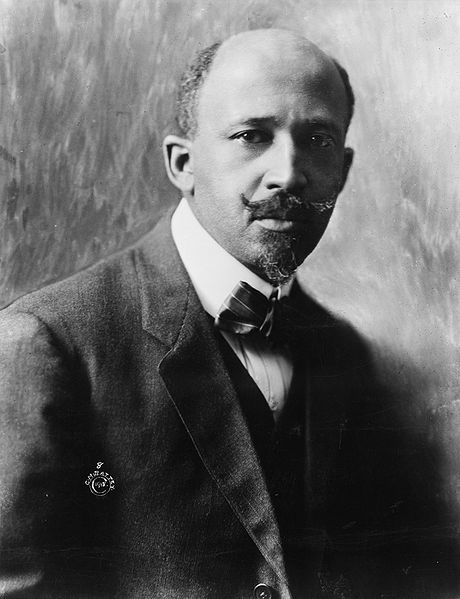

In some senses, slavery had already ended in many parts of the South before Lee’s surrender. Slaves mounted what W.E.B. Du Bois called a “general strike,” withdrawing their labor from the maintenance of the Confederacy and deploying it instead in support of the Union.

In his classic book Black Reconstruction, Du Bois elaborated:

Freedom for the slave was the logical result of a crazy attempt to wage war in the midst of four million Black slaves, and trying the while sublimely to ignore the interests of those slaves in the outcome of the fighting. Yet these slaves had enormous power in their hands. Simply by stopping work, they could threaten the Confederacy with starvation. By walking into Federal camps, they showed to doubting Northerners the easy possibility of using them as workers and as servants, as farmers, and as spies, and finally, as fighting soldiers…It was the fugitive slave who made the slaveholders face the alternative of surrendering to the North, or to the Negroes.

Slaves had this power because slavery had literally built U.S.–and, one could certainly argue, world capitalism. As Marx wrote in one of his earliest analyses of capitalism:

Direct slavery is as much the pivot upon which our present-day industrialism turns as are machinery, credit, etc. Without cotton there would be no modern industry. It is slavery which has given value to the colonies, it is the colonies which have created world trade, and world trade is the necessary condition for large-scale machine industry…Slavery is therefore an economic category of paramount importance.

One of these “colonies” Marx was referring to was, until 1783, under British control until it became the United States of America. Even though it threw off British rule, the new U.S. retained slavery as an essential element of its economy. In 1775, on the eve of the revolution, one out of five of the North American colonies’ 2.5 million people was an African slave. By the Civil War, the slave population was estimated at 4 million.

The increase in the slave population paralleled the crucial role slavery played in the new republic. In 1790, the U.S. produced almost no cotton. By 1860, it was producing 2 billion pounds annually. As Edward T. Baptist writes in his history of slavery and capitalism in the U.S. The Half Has Not Been Told:

The returns from cotton monopoly powered the modernization of the rest of the American economy, and by the time of the Civil War, the United States had become the second nation to undergo large-scale industrialization. In fact, slavery’s expansion shaped every crucial aspect of the economy and politics of the new nation–not only increasing its power and size, but also, eventually, dividing U.S. politics, differentiating regional identities and interests, and helping to make civil war possible.

The new republic faced a contradiction. It had proclaimed in its Declaration of Independence from Britain that “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

And yet its economy and its political institutions rested on a monstrous system that held millions of human beings in bondage. How could it square this circle? One critical way was the ideology of racism and white supremacy.

To be sure, racism–the oppression of a group of people based on the idea that some inherited characteristic, such as skin color, makes them inferior to their oppressors–didn’t just emerge in the 1770s. But it wasn’t, as many believe today, an ideology that existed for all time. Modern racism developed side by side with the development of chattel slavery in the period of the rise of capitalism.

As the Trinidadian historian of slavery Eric Williams put it: “Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” And, one can add, the consequence of modern slavery at the dawn of capitalism. While slavery existed as an economic system for thousands of years before the conquest of America, racism as we understand it today did not exist.

The African slave trade lasted for a little more than 400 years, from the mid-1400s, when the Portuguese made their first voyages down the African coast, to the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888.

Slave traders took as many as 12 million Africans by force to work on the plantations in South America, the Caribbean and North America. About 13 percent of slaves (1.5 million) died during the Middle Passage–the voyage by boat from Africa to the New World. The slave trade–involving African slave merchants, European slavers and New World planters in the traffic in human cargo–represented the greatest forced population transfer ever.

The slave trade helped to shape a wide variety of societies, from modern Argentina to Canada. They differed in their use of slaves, the harshness of the regime imposed on them, and the degree of mixing of the races that custom and law permitted. But no society became as virulently racist–insisting on racial separation and a strict color bar–as the English North American colonies that became the United States.

It is important to underscore that when the European powers began carving up the New World between them, African slaves were not part of their calculations.

When we think of slavery today, we think of it primarily from the point of view of its relationship to racism. But planters in the 17th and 18th centuries looked at it primarily as a means to produce profits. Slavery was a method of organizing labor to produce sugar, tobacco and cotton. It was not, first and foremost, a system for producing white supremacy. How did slavery in the U.S. (and the rest of the New World) become the breeding ground for racism?

For much of the first century of colonization in what became the U.S., the majority of slaves and other “unfree laborers” were white. The hallmark of systems like slavery and indentured servitude was that slaves or servants were “bound over” to a particular employer for a period of time, or for life in the case of slaves. The decision to work for another master wasn’t the slave’s or the servant’s. It was the master’s, who could sell slaves for money or other commodities, like livestock, lumber or machinery.

The North American colonies started predominantly as private business enterprises in the early 1600s. In addition to sheer survival, the settlers’ chief aim was to obtain a labor force that could produce the large amounts of indigo, tobacco, sugar and other crops that would be sold back to England. From 1607, when Jamestown was founded in Virginia to about 1685, the primary source of agricultural labor in English North America came from white indentured servants.

The colonists had first attempted to press the indigenous population into labor. But the Indians refused to be become servants to the English. They resisted being forced to work and were able to escape into the surrounding area, which, after all, they knew far better than the English. One after another, the English colonies turned to a policy of driving out the Indians.

The colonists then turned to white servants. Indentured servants were predominantly young white men–usually English or Irish–who were required to work for a planter master for some fixed term of four to seven years. The servants received room and board on the plantation, but no pay. They could not quit and work for another planter. They had to serve their term, after which they might be able to acquire land and start a farm for themselves.

For most of the 1600s, the planters tried to get by with a predominantly white, but multiracial workforce. But as the 17th century wore on, colonial leaders became increasingly frustrated with white servant labor. For one thing, they faced the problem of constantly having to recruit labor as their servants’ terms expired. Second, after servants finished their contracts and decided to set up their farms, they could become competitors to their former masters.

And finally, the planters didn’t like the servants’ “insolence.” The mid-1600s were a time of revolution in England, when ideas of individual freedom were challenging the old hierarchies based on royalty. The colonial planters tended to be royalists, but their servants tended to assert their “rights as Englishmen” to better food, clothing and time off.

Black slaves worked on plantations in small numbers throughout the 1600s. But until the end of the 1600s, it cost planters more to buy Black slaves than to buy white servants. Blacks lived in the colonies in a variety of statuses–some were free, some were slaves and some were servants.

The law in Virginia didn’t establish the condition of lifelong, perpetual slavery or even recognize African servants as a group different from white servants until 1661. Blacks could serve on juries, own property and exercise other rights. Northampton County, Virginia, recognized interracial marriages and, in one case, assigned a free Black couple to act as foster parents for an abandoned white child. There were even a few examples of Black freemen who owned white servants. Free Blacks in North Carolina had voting rights.

The planters’ economic calculations played a part in the colonies’ decision to move toward full-scale slave labor. By the end of the 17th century, the price of white indentured servants outstripped the price of African slaves. A planter could buy an African slave for life for the same price that he could purchase a white servant for 10 years. As Eric Williams explained:

Here, then, is the origin of Negro slavery. The reason was economic, not racial; it had to do not with the color of the laborer, but the cheapness of the labor. [The planter] would have gone to the moon, if necessary, for labor. Africa was nearer than the moon, nearer, too, than the more populous countries of India and China. But their turn would soon come.

The planters’ fear of a multiracial uprising also pushed them towards racial slavery. Because a rigid racial division of labor didn’t exist in the 17th century colonies, many conspiracies involving Black slaves and white indentured servants were hatched, though ultimately foiled.

The largest of these conspiracies developed into Bacon’s Rebellion, an uprising that threw terror into the hearts of the Virginia Tidewater planters in 1676. Several hundred farmers, servants and slaves initiated a protest to press the colonial government to seize Indian land for distribution. The conflict spilled over into demands for tax relief and resentment of the Jamestown establishment. Planter Nathaniel Bacon helped organize an army of whites and Blacks that sacked Jamestown and forced the governor to flee. The rebel army held out for eight months before the Crown managed to defeat and disarm it.

Bacon’s Rebellion was a turning point. After it ended, the Tidewater planters moved in two directions: First, they offered concessions to the white freemen, lifting taxes and extending to them the vote; and second, they moved to full-scale racial slavery.

Fifteen years earlier, the Burgesses had recognized the condition of slavery for life and placed Africans in a different category from white servants. But the law had little practical effect. As historian Barbara Jeanne Fields wrote: “Until slavery became systematic, there was no need for a systematic slave code. And slavery could not become systematic so long as an African slave for life cost twice as much as an English servant for a five-year term,”

Both of those circumstances changed in the immediate aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion. In the entire 17th century, the planters imported about 20,000 African slaves. The majority were brought to North American colonies in the 24 years after Bacon’s Rebellion.

In 1664, the Maryland legislature passed a law determining who would be considered slaves on the basis of the condition of their father–whether their father was slave or free. It became clear, however, that establishing paternity was difficult, but that establishing who was a person’s mother was definite. So the planters changed the law to establish slave status on the basis of the mother’s condition.

Taking the Maryland law as an example, Fields made this important point:

Historians can actually observe colonial Americans in the act of preparing the ground for race without foreknowledge of what would later arise on the foundation they were laying…[T]he purpose of the experiment is clear: to prevent the erosion of slaveowners’ property rights that would result if the offspring of free white women impregnated by slave men were entitled to freedom. The language of the preamble to the law makes clear that the point was not yet race…Race does not explain the law. Rather, the law shows society in the act of inventing race.

After establishing that African slaves would cultivate the major cash crops of the North American colonies, the planters then established the institutions and ideas that would uphold white supremacy. Most unfree labor became Black labor. Laws and ideas intended to underscore the subhuman status of Black people–in a word, the ideology of racism and white supremacy–emerged full-blown over the next generation.

Within a few decades, the ideology of white supremacy was fully developed. Some of the best known intellectual giants of the day–such as Scottish philosopher David Hume and Thomas Jefferson, who would write the Declaration of Independence–wrote treatises alleging Black inferiority.

The American Revolution was aimed at establishing the rights of the new capitalist class against the old feudal monarchy. But the challenge to British tyranny also gave expression to a whole range of ideas that expanded the concept of “liberty” from being just about trade to include ideas of human rights, democracy and civil liberties. Some of the leading American revolutionaries, such as Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, endorsed abolition.

But because the revolution aimed to establish the rule of capital in America, and because a lot of capitalists and planters made a lot of money from slavery, the revolution compromised with slavery. With few exceptions, no major institution in the new republic–not the universities, nor the churches, nor the newspapers of the time–raised criticisms of white supremacy or slavery. In fact, they bolstered the religious and academic justifications for slavery and Black inferiority. As the Marxist C.L.R. James wrote:

[T]he conception of dividing people by race begins with the slave trade. This thing was so shocking, so opposed to all the conceptions of society which religion and philosophers had, that the only justification by which humanity could face it was to divide people into races and decide that the Africans were an inferior race.

White supremacy wasn’t only used to justify slavery. It was also used to keep in line the two-thirds of Southern whites who weren’t slaveholders. A tiny minority of slave-holding whites, who controlled the governments and economies of the Deep South states, ruled over a population that was roughly two-thirds white farmers and workers and one-third Black slaves.

The slaveholders’ ideology of racism and white supremacy helped to divide the working population, tying poor whites to the slaveholders. The great abolitionist Frederick Douglass understood this dynamic:

The hostility between the whites and Blacks of the South is easily explained. It has its root and sap in the relation of slavery, and was incited on both sides by the cunning of the slave masters. Those masters secured their ascendancy over both the poor whites and the Blacks by putting enmity between them. They divided both to conquer each. [Slaveholders denounced emancipation as] tending to put the white working man on an equality with Blacks, and by this means, they succeed in drawing off the minds of the poor whites from the real fact, that by the rich slave-master, they are already regarded as but a single remove from equality with the slave.

Slavery in the colonies helped produce a boom in the 18th century economy that provided the launching pad for the industrial revolution in Europe. From the start, colonial slavery and capitalism were linked. While it isn’t correct to say that slavery created capitalism, it is correct to say that slavery provided one of the chief sources for the initial accumulations of wealth that helped to propel capitalism forward in Europe and North America.

The clearest example of the connection between plantation slavery and the rise of industrial capitalism was the connection between the cotton South, Britain and, to a lesser extent, the Northern industrial states.

Here, we can see the direct link between slavery in the U.S. and the development of the most advanced capitalist production methods in the world. Cotton textiles accounted for 75 percent of British industrial employment in 1840, and, at its height, three-quarters of that cotton came from the slave plantations of the Deep South. And Northern ships and ports transported the cotton.

To meet the boom in the 1840s and 1850s, the planters became even more vicious. On the one hand, they tried to expand slavery into West and Central America. The fight over the extension of slavery into the territories eventually precipitated the Civil War in 1861. On the other, they drove their existing slaves harder–selling more cotton to buy more slaves just to keep up. On the eve of the Civil War, the South was petitioning to lift the ban on the importation of slaves that had existed officially since 1808.

The close connection between slavery and capitalism, and thus, between racism and capitalism, gives the lie to those who insist that slavery would have just died out. In fact, the South was more dependent on slavery right before the Civil War than 50 or 100 years earlier. Slavery lasted as long as it did because it was profitable. And it was profitable to the richest and most “well-bred” people in the world.

In abolishing slavery, the Civil War struck a great blow against racism. Almost a week before Appomattox, the Confederate capital of Richmond fell into Union hands. While most of the city’s whites seemed to desert the place, Blacks flooded into the streets to greet the arriving Federal troops. A Union chaplain wrote:

The slaves seemed to think that the day of jubilee had fully come. How they danced, shouted…shook our hands…and thanked God, too, for our coming…It is a day never to be forgotten by us, till days shall be no more.

Abolishing slavery accomplished a social revolution. The Civil War’s destruction of slavery was the largest expropriation of private property in history to that point, and for half a century after.

And beyond the economic statistics lay an even more profound social transformation, as a story recounted by the historian Leon Litwack illustrated. After the war, a Black Union soldier recognized his former master among a group of Confederate prisoners he was guarding. The soldier called out to his former master: “Hello, massa, bottom rail on top dis time!”

The Resistance to History’s Enormous Crime

By Alan Maass

THE RISE of the United States to become the richest nation ever known is bound up with one of the most barbaric crimes in all history–the enslavement of Africans to be laborers in the “New World.”

It’s impossible to overstate the horrors of the slave system that thrived in America right up until the Civil War ended it 150 years ago–the “Middle Passage” of kidnapped Africans transported across the Atlantic, costing the lives of one-sixth of the human “cargo”; families ripped apart on the auction block in genteel Southern cities; maximum violence used to extract the maximum possible labor from the slaves.

Plus, there was the day-to-day misery described by the former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass: “The overwork and the brutal chastisements of which I was the victim, combined with the ever-gnawing and soul-devouring thought–‘I am a slave, and a slave for life, a slave with no rational ground to hope for freedom’–rendered me a living embodiment of mental and physical wretchedness.”

But the history of slavery is also a history of resistance–one that is disgracefully ignored or downplayed today even more often than the system’s atrocities are.

The first steps in the struggle were taken by slaves themselves, but the cause of abolition was taken up by Black and white, and grew into a massive movement by the middle of the 19th century–one that was more and more dedicated to the revolutionary overthrow of the slave system.

The slave resistance was rooted in countless small acts of defiance and opposition–feigning illness to avoid work or breaking tools to slow down the pace of work. Slaves developed a culture of resistance, too, converting work songs into expressions of their desire to be free–and, likewise, the Christianity taught to them by the masters.

In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass describes how his fury was directed at a violent overseer. “I was a changed being after that fight,” Douglass wrote. “I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, though I still remained a slave in form.”

More often than is commonly acknowledged, this spirit erupted in mass slave revolts. The most famous was the uprising in Virginia led by Nat Turner in August 1831, but there were more. Four years later, for example, an alliance of Native Americans, escaped slaves, plantation hands and free Blacks organized as a fighting force against the U.S. Army. The radical historian Herbert Aptheker documented more than 250 revolts on plantations and another 55 mutinies on slave ships.

None of these revolts was able to survive against the terrorist system run by the Southern slave owners, who could rely on the government at every level, up to and including the federal, to crush any uprising.

Despite the repression, a system to aid slaves escaping bondage–the Underground Railroad, supported by a variety of conspiratorial organizations in the U.S. and Canada–took shape and helped an estimated 100,000 people escape by 1850. Especially during the later years, most of the railroad’s conductors were Black.

When the slave power tried to reach into the North to kidnap Blacks accused of being fugitives, it was met by direct action and not-so-civil disobedience led by those in the best position to know their enemy.

For example, in 1793, a Massachusetts lawyer named Josiah Quincy was defending a man accused of being a runaway slave. According to his biographer, as Quincy got up to make his argument, a group of Black people came into the courtroom–Quincy turned around and “saw the constable lying on the floor, and a passage opening through the crowd, through which the fugitive was taking his departure without stopping to hear the opinion of the court.”

Before the slave system was finally overthrown 150 years ago, a majority of people in the North had turned against the Southern slaveocracy. But as Herbert Aptheker wrote, Blacks, whether enslaved or free:

were the first and most lasting Abolitionists…Without the initiative of the Afro-American people, without their illumination of the nature of slavery, without their persistent struggle to be free, there would have been no national Abolitionist movement. And when the movement did appear, the participation of Black people in every aspect was indispensable to its functioning and its eventual success.

Beyond the victims themselves, there was sentiment against slavery from the founding of United States. Leading voices of the American Revolution like Tom Paine and Benjamin Franklin recognized the hypocrisy of a country that claimed “all men are created equal” in its Declaration of Independence, but where 1 million people were owned as human property at the time.

But the dominant opinion was that slavery would eventually die out, and therefore nothing more than moral persuasion was needed. This view was proved wrong within a few decades of the founding of the U.S., and the reason why can be summed up in one word: cotton.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made mass production possible at the moment when the Industrial Revolution, based on textile manufacturing, was taking off in Britain. In the next two decades, U.S. cotton exports grew from 500,000 pounds to more than 80 million pounds a year, representing a majority of American trade by a large margin.

The great fortunes of America and of Europe were founded on a system with slave labor at their heart. As Karl Marx wrote in a letter, “Without slavery there would be no cotton, without cotton there would be no modern industry.”

So slavery didn’t die away–the pace of exploitation was massively intensified. In the South, purely moral opposition to slavery fell away, and if it didn’t, it was driven out. Abolitionism became centered in the North among supporters who inevitably reached radical conclusions–that slavery was not some stain that would eventually fade out, but a system that would have to be rooted out.

In 1827, a group of Blacks in New York launched an antislavery newspaper called Freedom’s Journal. The distribution network for the paper was also a circle of political agitators who traveled widely to organize. Among the paper’s agents was David Walker, whose Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World–published a little over a year before Nat Turner’s revolt–struck fear into the hearts of Southerners.

The publications and political ideas put forward by Blacks, many of them escaped from slavery themselves, shaped a new generation of abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, a white Massachusetts printer and journalist. In 1831, he launched the weekly newspaper The Liberator, which would be a call to action to abolitionists breaking from old ideas. As Frederick Douglass remembered in his autobiography:

The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds–its scathing denunciations of slaveholders–its faithful exposures of slavery–and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution–sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before!

At the national level, slavery’s grip grew tighter than ever in this era, both economically and politically. But the rise of the new phase of abolitionism showed that there was fertile ground in the North for a resistance to take root and spread.

By late 1837, Garrison estimated that there were “not less than 1,200 anti-slavery societies in existence”–a sixfold increase in just a few years, and with a total membership of more than 100,000 people.

This growth was the result of the hard work of political organizing–of the kind that radicals of every era, including today, would recognize.

Public meetings were probably the primary way that abolitionists reached their audience. In cities and towns across the North, dozens and hundreds and even thousands would pack into lecture halls to hear speakers.

The editor of Frederick Douglass’ speeches and writings estimated that a “partial” list of speaking events for Douglass, just in one month in 1855, included at least 21 addresses, in cities from Maine and Massachusetts to New York and Pennsylvania. All told, between 1855 and 1863, Douglass gave more than 500 known speeches in the U.S., Britain and Canada.

Papers like Garrison’s Liberator were chronically short of funds, but maintained a growing readership, even as the number of newspapers multiplied. Pamphlets, often based on the speeches of abolitionist agitators, reached hundreds of thousands of people. Published in 1845, Frederick Douglass’ autobiography sold 5,000 copies in four months and some 30,000 by the start of the Civil War a decade and a half later.

After a yearlong petition campaign that began in 1837, the American Anti-Slavery Society announced that 414,471 people had signed a petition calling on Congress to end slavery and the slave trade in the District Columbia. Another petition drive to lift the gag rule on Congress discussing anti-slavery resolutions got 1 million signatures from across the Northern states.

Such accomplishments would have been impossible without a well-trained core of activists. Thus, Herbert Aptheker’s Abolitionism describes a “school” organized in November 1836:

Theodore Weld had recruited about 50 people prepared to devote themselves to spreading the movement’s message. Most of them attended what might well be called, in modern terms, a cadre-training school in New York City. From November 15 through December 2, these volunteer students heard the questions most commonly asked of abolitionists; suggesting appropriate answers were experts Theodore Weld, the Grimké sisters–Angelina and Sarah–William Lloyd Garrison, James G. Birney and others.

This new phase of abolitionism was unapologetically radical and uncompromising, but its main ideas can seem strange from the vantage point of today.

Garrison and his followers rejected involvement in politics. They believed slavery would be overthrown by building overwhelming moral pressure against the slave owners, that the anti-slavery movement must be nonviolent, and that the North should secede from the U.S. rather than remain united with the slave South.

But this represented a significant advance in a movement where the dominant belief had been that emancipation would come gradually, through existing institutions. The hostility to political involvement was a response to the corruption of a U.S. political system that accepted endless compromises with the slaveocracy–a system where the Constitution itself was “infected with the pestilence of slavery,” as Garrison wrote.

The anti-slavery struggle was bound up with discussions and disagreements about these ideas, but Garrison’s philosophy was the ground on which the debates began. Frederick Douglass was a devoted Garrisonian for a decade after his escape from slavery in 1838, until he helped lead a further radical transformation of the movement, directed toward engagement with politics.

One of the most famous critics of Garrison’s insistence on nonviolence was the Black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet, who called for a general strike of slaves at the National Negro Convention in 1843: “Let every slave throughout the land do this, and the days of slavery are numbered…Let your motto be resistance! resistance! resistance!” Yet Garnet’s first political act while a student in New York City was to form the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association.

What Douglass and Garnet recognized in Garrison, whatever their later differences, was a devotion to the struggle, no matter what sacrifice or suffering had to be endured. Another eventual leader of the movement, Wendell Phillips, remembered later that he first saw Garrison in 1835 when the Liberator editor was being dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob of anti-abolitionists who wanted to lynch him.

The radicalism of the abolitionists in this era came out on other social and political questions. For example, the anti-slavery struggle “was the first great social movement in U.S. history in which women fully participated in every capacity: as organizers, propagandists, petitioners, lecturers, authors, editors, executives and especially rank-and-filers,” Aptheker wrote.

Abolitionists saw their fight against slavery as connected to an international one for democracy and freedom. Garnet, writing in Douglass’ newly founded newspaper North Star, greeted the great wave of European revolts of 1848 as the sign of “a revolutionary age” in which “revolution after revolution will undoubtedly take place until all men are placed upon equality.”

Until the 1850s at least, abolitionists were still a minority–often a persecuted one–in the North, where hostility to the Southern slaveocracy coexisted among many ordinary whites with hostility to the slave. Garrison in particular was known for chastising the labor movement in the Liberator. But on this issue, too, ideas shifted. In 1849, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society passed a resolution declaring:

Whereas the rights of the laborer of the North are identical with those of the Southern slave, and cannot be obtained as long as chattel slavery rears its hydra head in our land; and whereas, the same arguments which apply to the situation of the crushed slave, are also in force in reference to the condition of the Northern laborer–although in a less degree; therefore, Resolved, That it is equally incumbent upon the working men of the North to espouse the cause of the emancipation of the slave and upon Abolitionists to advocate the claims of the free laborer.

Abolitionists were determined to challenge racism among Northerners, including bigotry or paternalism within their own ranks–an absolute necessity in a struggle where Black abolitionists played a central role. The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838 adopted a resolution proposed by Sarah Grimké that insisted:

It is the duty of Abolitionists to identify themselves with these oppressed Americans, by sitting with them in places of worship, by appearing with them in our streets, by giving them our countenances in steamboats and stages, by visiting them in their homes, and encouraging them to visit us, receiving them as we do our fellow citizens.

As the 19th century continued, every year brought new confirmation of how the institution of slavery was woven into the fabric of American political and economic power. As Wendell Phillips explained in a speech in Boston in 1852–with Garrison alongside him on the platform:

Every thoughtful and unprejudiced mind must see that such an evil as slavery will yield only to the most radical treatment. If you consider the work we have to do, you will not think us needlessly aggressive, or that we dig down unnecessarily deep in laying the foundation of our enterprise.

A money power of two thousand millions of dollars, as the prices of slaves now range, held by a small body of able and desperate men; that body raised into a political aristocracy by special constitutional provisions, cotton, the product of slave labor, forming the basis of our whole foreign commerce, and the commercial class so subsidized, the press bought up, the pulpit reduced to vassalage, the heart of the common people chilled by a bitter prejudice against the Black race; our leading men bribed, by ambition, either to silence or open hostility; in such a land, on what shall an Abolitionist rely?…

[T]he old jest of one who tries to lift himself in his own basket is but a tame picture of the man who imagines that, by working solely through existing sects and parties, he can destroy slavery.

There were many economic and social factors driving what New York political leader William Seward called the “irrepressible conflict” between North and South. But in the first six decades of the 19th century, each time North and South came to the brink, the Northern business and political elite accepted a compromise that allowed the slaveocracy to continue to reign.

The revolutionaries of the abolitionist movement were essential in pushing that conflict to the breaking point at long last.

The Road to Civil War

One evening in November 1820, John Quincy Adams–the son of a former president, the current Secretary of State, and a president himself in four year’s time–made a bold prediction:

If slavery be the destined sword in the hand of the destroying angel which is to sever the ties of this Union, the same sword will cut in sunder the bonds of slavery itself. A dissolution of the Union for the cause of slavery would be followed by a servile war in the slave-holding States, combined with a war between the two severed portions of the Union. It seems to me that its result must be the extirpation of slavery from this whole continent; and calamitous and desolating as this course of events in its progress must be, so glorious would be its final issue that, as God shall judge me, I dare not say that it is not to be desired.

Adams confided this speculation to his diary, but if he did speak it out loud, his listeners probably would have been taken aback. In 1820, the idea that slavery would be the cause of a war between North and South might have seemed like a shadowy possibility–but a Southern defeat, followed by “extirpation of slavery from this whole continent,” no more than an abolitionist’s fantasy.

After all, the Southern ruling class’s wealth and power was reaching new heights, based on the intensified exploitation of Black slaves to produce the cotton that fueled the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Congress had recently agreed to the Compromise of 1820–the latest in a series of compromises that didn’t just leave the cornerstone of Southern wealth intact, but allowed the slaveocracy to continue to dominate the federal government.

Nevertheless, Adams’ prediction was vindicated to the letter 45 years later–in April 1865, at the end of four bloody years of a Civil War that did ultimately destroy the institution of slavery.

The conflict between North and South–with their two different social systems, one based on slave labor and the other free–was obvious enough by 1820. What Adams foresaw with greater clarity was, first, this conflict with economic and social roots would be fought out in the political arena; second, every time it was resolved in favor of the South, it would be at the expense of democracy and justice in every corner of society; and third, when the North was finally powerful enough to prevail politically, it would undermine the South’s power and seal its fate.

It’s as if Adams was paraphrasing the words of another fierce advocate for democracy, but from the 20th century. The arc of the moral universe may be long, Adams was saying, but it bends toward emancipation.

Still, as much as the North and South were set on a collision course toward the “irrepressible conflict,” as it became known, the shape and timing and outcome of that conflict depended very much on the organization of those determined to bring down the slave system.

The “irrepressible conflict” was present from the founding of the United States.

The American Revolution, fought to end British rule in its North American colonies, gave expression to the highest democratic ideals of the era. More than a decade before “liberté, égalité, fraternité” became the slogan of the French Revolution, America’s Declaration of Independence stated that “all men are created equal.”

But of course, all men weren’t equal in America. At the time of the revolution, there were more than 1 million African slaves in the colonies.

Even at this point, slavery was concentrated in the South–the system of forced labor was suited to the plantation agriculture system. The boom in cotton production in the early 19th century–driven by the demand of an international capitalist system in the midst of the Industrial Revolution–led to an intensification of all the horrors of slavery. The domination of an oligarchy of big plantation owners over Southern society and politics was cemented in place.

The colonies-turned-states of the North developed in a different direction. The merchant elite of the North was tied up with the slave system because of its position in financing and shipping the South’s cotton crop to Europe. But Northern agriculture was dominated by smaller farmsteads and different crops.

More importantly, as the cotton boom took off in the South, industry began to develop nearly as rapidly in the North. The factory system created in Britain spread through New England. By one estimate, by 1840, the value of manufacturing assets concentrated in Providence, Rhode Island–more than 150 factories employing 30,000 men and women–made it the richest city in the world.

The North experienced a further boom after 1840 based on the development of steam power–railroads became the dominant form of transportation in less than a generation. Northern cities grew rapidly, even as the population expanded westward into the upper Midwest and beyond.

In this regard, the North was at least the equal of the South in a different form of barbarism–driving Native Americans off their land and destroying their livelihoods and culture. On this issue, the North and South were united–even the abolitionists appear to have been either oblivious to or silent about this historic crime, at least until after the Civil War.

On virtually every other question, though, the North and South were at odds–and the battles between these rival systems, while rooted in economics, played out in political disputes.

On the issue of trade, for example, the Southern plantation owners wanted free trade policies as the basis of an export economy, while Northern industrialists wanted tariffs to protect their new industrial enterprises. The North needed the federal government to devote financial resources to develop new systems of transportation and spur business innovation, while Southerners wanted the government to stay out of the economy.

Contemporary historians and commentators who want to obscure slavery as the central cause of the Civil War sometimes focus on these other sources of conflict as if they were of equal importance. But all the other frictions flowed out of the essential conflict between two competing social systems, one based on slave labor and the other on free labor.

The different ideological expressions of North and South help illustrate the point. In the North, ideals of democracy and individual freedom, even if they were filtered through the rhetoric of capitalism, could thrive in a society where there was a certain amount of class mobility and economic opportunity. In the South, though the ruling class was enmeshed in an international capitalist system, the dominant ideology reflected anti-democratic prejudices common to the European aristocracy for centuries beforehand.

One article in a Georgia newspaper gave expression to the mindset: “Free Society! We sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of greasy mechanics, filthy operatives, small-fisted farmers and moon-struck theorists…hardly fit for association with a Southern gentleman’s body servant.”

Writing from England as the Civil War was just underway in late 1861, Karl Marx–the keenest of all contemporary observers of the war–emphasized the heart of the North-South conflict:

The whole movement was and is based, as one sees, on the slave question. Not in the sense of whether the slaves within the existing slave states should be emancipated outright or not, but whether the 20 million free men of the North should submit any longer to an oligarchy of 300,000 slaveholders.

In the decades before the war, each time the conflict between North and South came to a head, it had to be papered over with a political compromise–and each one favored the Southern ruling class, at the expense of the North.

The most famous compromise of all was enshrined in the Constitution itself, which is why abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison considered it to be “infected with the pestilence of slavery.” Slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person (Native Americans were not counted at all) for the purposes of allocating representation in the federal government. This gave the South a built-in advantage and helped it to dominate the White House and the Supreme Court for most of the years until the Civil War.

Subsequent compromises typically came down to the make-or-break question of admitting new states into the Union as slave states or free states. Every new free state threatened to tip the balance of power in the U.S. Senate–with its undemocratic two representatives per state, regardless of population–to the Northern side.

The Southern ruling class would stop at nothing to maintain its political domination. In the mid-1840s, the pro-slavery President James Polk launched a war on Mexico, with the clear aim of seizing new territories in the West that could be brought into the U.S. as slave states.

The Compromise of 1850 allowed California into the union as a free state, but at the cost of more concessions to Southern power–including the Fugitive Slave Act, which put the force of the federal government behind the vigilante slave-catchers who kidnapped Blacks from the North, claiming they were escaped slaves.

The Northern ruling class chafed under a political system that kept them, despite their growing economic power, subordinate to their rivals in the South. But the popular effect of the compromises was far more profound.

Among the abolitionists, already committed to the cause of ending slavery, each compromise drove them to more radical positions–including challenging the prevailing orthodoxies of the movement, like nonviolence.

Frederick Douglass, the former slave and well known abolitionist agitator, had already broken with Garrison over nonviolence by 1850, but the Fugitive Slave Act reinforced that direction. “The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter,” Douglass said, “is to make a half-dozen or more dead kidnappers.”

The new law infuriated even moderate opponents of slavery. “This filthy enactment was made in the 19th century by people who could read and write,” wrote the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. “I will not obey it, by God.”

Among the Northern population generally, resentment at the power of the Southern ruling class to dictate national policies remained a central factor. Northern farmers, for example, wanted the same territories that the slaveocracy hoped to settle as slave states. But specifically anti-slavery sentiment continued to spread in the 1840s and ’50s, driven by the campaigns of the abolitionists, but also by each new outrage like the Fugitive Slave Act.

So, for example, in 1854, Anthony Burns, a former slave living in Boston, was ordered to be returned to slavery. That night, a riotous crowd nearly freed him from the jail where he was being held. The next day, Burns had to be guarded by hundreds of police as he was led to the harbor to be put on board a ship bound for the South.

“We went to bed one night old-fashioned conservative Compromise Union Whigs, and waked up stark mad abolitionists,” wrote one Boston resident. From the other side, the Richmond Enquirer newspaper in Virginia commented: “One more victory like that, and the South is lost.”

That same year brought a mini-Civil War after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The law created two new territories that would soon become states–but whether they were free or slave was left to a popular vote. Thousands of pro-Southern settlers known as “border ruffians” descended on Kansas to rig the vote in favor of slavery. The battle between these vigilantes and free state forces continued until the outbreak of the Civil War itself.

Among the abolitionists who went to Kansas to fight on the free state side was John Brown. A few years later, he and his sons came back east to carry out a long-planned military operation, with the goal of sparking a general uprising against slavery.

In October 1859, Brown and a small band of men, Black and white together, carried out a raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The raiders succeeded in capturing the armory, but before they escaped with the weapons they intended to distribute among slaves, they were surrounded. Brown was arrested by a U.S. Army unit led by the future Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. After a show trial that Brown nevertheless turned into an indictment of slavery, the captured raiders were put to death.

The Harpers Ferry raid showed that the conflict between North and South was past the point of compromise. The South was convulsed by fear that a slave insurrection, backed by warriors from the North, was at hand. In the North, Brown was celebrated as a hero and martyr. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow declared that Brown’s hanging would be “a great day in our history, the date of a new Revolution–quite as needed as the old one.”

Frederick Douglass, who Brown nearly convinced to join the Harpers Ferry raid, credited his friend with setting the Civil War in motion:

If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did, at least, begin the war that ended slavery…Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises. When John Brown stretched forth his arm, the sky was cleared–the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union, and the clash of arms was at hand.

There was one more ingredient in the combustible mix that erupted into the Civil War: the Republican Party.

Strange as it might sound with today’s Tea Partying GOP in mind, the Republicans were once hated by the racist reactionaries of the slave South. The New Orleans Daily Delta newspaper called them “essentially a revolutionary party…[made up of] a motley throng of Sans culottes…Infidels and freelovers, interspersed by Bloomer women, fugitive slaves and amalgamationists.”

In reality, the Republicans were not nearly as radical as the slaveocracy feared them to be. They formed in 1854 as a third-party challenge, under the influence of the abolitionists, but also a range of other political forces, including anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Nativists.

The point of unity was opposition to the political power of the Southern elite. Beyond anything else, the different elements of the party wouldn’t accept expansion of slavery into new territories–and potential new states–in the West.

For the 1860 presidential election, more prominent abolitionist voices were passed over for the Republican nomination in favor of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln, who had been a member of Congress from Illinois, was personally opposed to slavery and expected to see it ended over time. But he specifically denied that he favored “the social and political equality of the white and Black races,” as he put it in one political debate. Lincoln won the nomination because he was at the middle point between the different factions of the Republican Party.

Frederick Douglass had supported third-party election challenges in past–by now, he had broken with another orthodoxy of the earlier phase of the abolitionist movement: the rejection of politics preached by William Lloyd Garrison.

As the 1860 election approached, Douglass zeroed in on the contradictions of Lincoln and the Republicans:

The Republican Party…is opposed to the political power of slavery, rather than to slavery itself. It would arrest the spread of the slave system…and defeat all plans for giving slavery any further guarantee of permanence. This is very desirable, but it leaves the great work of abolishing slavery…still to be accomplished. The triumph of the Republican Party will only open the way for this great work.

Nevertheless, Douglass disagreed with other abolitionists who called for boycotting the 1860 election. He recognized that a victory for Lincoln and the Republicans–against a divided Democratic Party, with one candidate representing the Southern slave-owning wing and another the Northern wing–really would “open the way for this great work.” As Douglass wrote a few months before the election:

I cannot fail to see that the Republican Party carries with it the anti-slavery sentiment of the North, and that a victory gained by it in the present canvass will be a victory gained by that sentiment over the wickedly aggressive pro-slavery sentiment of the country…The slaveholders know that the day of their power is over when a Republican president is elected.

Douglass’ words were prophetic. Lincoln’s victory spurred the secession of Southern states–seven of the 11 had broken with the Union before he took the oath of office.

As timid as it might have seemed to the radical abolitionists, the Republicans’ commitment to opposing the expansion of slavery would inevitably undermine the South’s dominant position in the federal government–and that would be the beginning of the end.

In his inaugural speech, Lincoln pledged, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” It was an offer of compromise to save the Union, which he insisted was his highest priority.

But Lincoln would only go so far. Various business figures and fellow Republicans urged him to accept a compromise that scrapped opposition to the expansion of slavery. On this, Lincoln refused to bend:

We have just carried an election on principles fairly stated to the people. Now we are told in advance, the government shall be broken up unless we surrender to those we have beaten…If we surrender, it is the end of us. They will repeat the experiment upon us ad libitum. A year will not pass till we shall have to take Cuba as a condition upon which they will stay in the Union.

The die was cast. A little over one month after Lincoln’s inauguration, the first shots of the Civil War were fired–the Confederacy’s bombardment of the federal government’s Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina.

To Save the Union or Free the Slaves?

By Donny Schraffenberger and Alan Maass

On April 2, 1865–one week before the surrender at Appomattox that ended the Civil War–the Confederate capital of Richmond was evacuated. After the Confederate Army left, Southerners burned their own city.

Among the Northern forces that first occupied Richmond in these weeks 150 years ago was the 25th Corps of the Union Army–a unit made up almost entirely of Black soldiers. They helped patrol the city and put out the fires. The final end of the white slave republic in the U.S. South was being overseen by former slaves, now soldiers in the Union Army.

On April 4, two days after the Confederate forces evacuated Richmond, President Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad visited the still smoldering ruins of the city. As they arrived, Lincoln was instantly recognized by former slaves, who greeted him ecstatically. As Admiral David Porter, who traveled with Lincoln, later wrote:

No electric wire could have carried the news of the president’s arrival sooner than it was circulated through Richmond. As far as the eye could see the streets were alive with negroes and poor whites rushing in our direction, and the crowd increased so fast that I had to surround the President with the sailors with fixed bayonets to keep them off…They all wanted to shake hands with Mr. Lincoln.

Lincoln–who four years before, weeks before the first shots were fired in the Civil War, had offered to support a constitutional amendment guaranteeing slavery in the states where it existed–was deeply moved by these celebrations. Another officer described Lincoln asking a man who had knelt before him to rise, saying:

Don’t kneel to me. That is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter. I am but God’s humble instrument; but you may rest assured that as long as I live, no one shall put a shackle on your limbs, and you shall have all the rights which God has given to every other free citizen of this Republic.

Similarly joyous scenes played out in the months and years before the South finally admitted defeat in April 1865. They confirmed what had seemed uncertain four years before to all but the most far-sighted abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Karl Marx–that the Civil War would revolve around the revolutionary aim of destroying the institution of slavery and the Southern ruling class that depended on it.

Douglass had been critical of Lincoln for not embracing this aim from the beginning. Confederate forces started the war with the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the federal fort guarding harbor in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861. At this point, Douglass wrote, both sides, North and South, were fighting “in the interests of slavery…The South was fighting to take slavery out of the Union, and the North was fighting to keep it in the Union.”

What Douglass meant was that Lincoln had made it clear he would accept a Union where slavery still existed in the South. However, Lincoln and the recently formed Republican Party were adamant about stopping the spread of slavery to new territories and states. The South, meanwhile, wasn’t satisfied with preserving slavery where it existed. It not only wanted new slave states–some Southern leaders proposed to conquer Cuba and Central America as new places to expand the slave South.

This issue–whether slavery would expand or not–was what finally brought the long-running conflict between the Southern slaveocracy and the Northern system based on free labor to a head. All the previous clashes had been papered over with compromises that maintained the balance of power between slave states and free states so the South could continue to dominate the federal government. The South held the balance of power in the Senate and U.S. Supreme Court for almost all the years leading to 1861.

When Lincoln was elected president in 1860 on a platform of stopping any further expansion of slavery, the slave power recognized that this was the beginning of the end of its dominant position–because further expansion of states where slavery was illegal would tip the balance to the North in the Senate and eventually the Court. Most of the states of the Confederacy had seceded from the Union by the time Lincoln took the oath of office.

Still, when the Civil War began, most people in the North thought it would be over in a few months. Lincoln called for volunteers for 90 days of service. He hoped that a majority of white Southerners were still loyal to the federal government and would come to their senses against the leaders of the newly seceded Southern states. Instead, the call for volunteers caused more states to secede.

During the first two years of the war, the North did poorly in the war’s Eastern theater–the primary battleground was located in Virginia, east of the Appalachian Mountains. The Confederate Army won overwhelming victories, including the battles of Bull Run, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

Popular histories of the Civil War often claim that these Confederate successes were the result of the superiority of the South’s generals, like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. In fact, the commander of the Northern forces, Gen. George McClellan, was renown within the Army for his technical skills as a military strategist. The problem was that he was utterly disinterested in fighting the war against the Confederacy.

McClellan was a supporter of the Democrats, the party of slavery in the South and of pro-slavery sentiment in the North. He represented a wing of the Northern elite that wanted to preserve the U.S. as it was before the South seceded, with slavery and the Southern ruling class intact. They wanted the war to impact Southern society as little as possible–enough to return the seceded states to the Union, perhaps, but not enough to threaten the lucrative plantation system, based on the exploitation of slave labor.

So McClellan pursued a timid war strategy consistent with this aim. The commander of Union forces became notorious for overestimating the size of the Confederate troops his men were fighting–and using this as an excuse not to advance. The South, commanded by generals wholly committed to the slaveocracy winning the war, were able to rout numerically superior Northern forces on a regular basis.

For all his political differences with McClellan and the Democrats, Lincoln showed indecision himself in this early period–tellingly, on the issue of slavery.

For example, in August 1861, Major Gen. John Frémont, in command of Union forces in the West, issued an order declaring martial law in Missouri and emancipating the slaves of any owners who took up arms. Missouri was a slave state that had stayed in the Union, but pro-Confederate forces were gaining strength.

Frémont, an abolitionist and the Republican Party’s presidential candidate four years before Lincoln ran in 1860, saw the order as a way to strengthen the resolve of the Union side in Missouri against the violence of the pro-Confederate forces. Abolitionists cheered the Frémont Proclamation, but Lincoln feared that it would alarm the so-called Border States–slave states like Missouri that had stayed a part of the Union–and push them into the Confederacy. He forced Frémont to rescind the order and then maneuvered to have him replaced.

Frederick Douglass was furious. “To fight against slaveholders without fighting slavery is but a half-hearted business and paralyzes the hands engaged in it,” he wrote. “Fire must be met with water. War for the destruction of liberty must be met with war for the destruction of slavery.”

One of the myths of the Civil War is that the North won because it had a larger population and greater resources to draw on–particularly its industrial production and transportation system. These were, indeed, necessary for the North to prevail, but not enough by themselves. The North also needed the political will to defeat the slaveocracy.

Political and ideological factors were bound to play a greater role in the Civil War. Both the North and South relied on volunteer armies–to a greater extent than any other U.S. war, according to historian James McPherson. The living conditions for soldiers were bad, the pay was low–and beyond that, the carnage of the Civil War was unparalleled.

The war caused the deaths of some 750,000 soldiers and an unknown number of civilians–amounting, by one estimate, to around 10 percent of all Northern males between the ages of 20 and 45 and more than 30 percent of Southern white males between 18 and 40. The casualty rate in the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 was four times greater than in the D-Day invasion of France during the Second World War.

To endure this suffering and slaughter required more than the usual forms of coercion that keep all wars as “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” The Civil War required a greater level of political understanding and commitment.

The South, of course, had clear aims from the start of the war, but the aims of the North had to develop and mature, particularly among the rank-and-file soldiers of the Union Army. Slavery was the key. As James McPherson wrote in his book What They Fought For 1861-1865:

Whereas a tacit agreement united Confederate soldiers in support of “Southern institutions,” including slavery, a bitter and explicit disagreement about emancipation divided northern soldiers…[U]nlike Confederate opinion on slavery, which remained relatively constant until the final months of the war, Union opinion was in a state of flux. It moved by fits and starts toward an eventual majority in the favor of abolishing slavery as the only way to win the war and preserve the Union.

Douglass was right: A war against slaveholders had to become a war against slavery for the North to prevail. The transformation began first as a matter of military necessity–and above all, because slaves forced the issue by escaping to the lines of the Union Army.

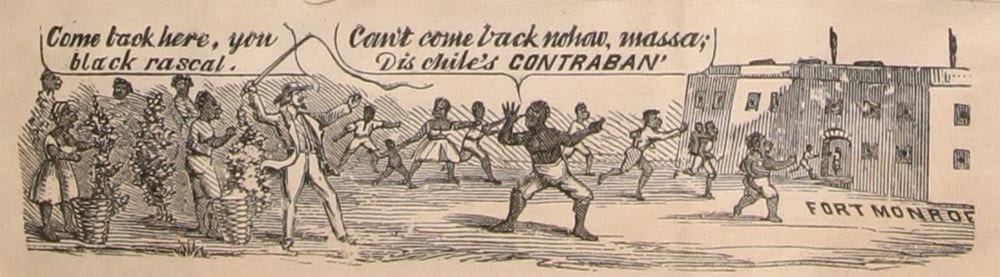

From the beginning of the war, thousands of slaves recognized that their fate was bound up with the outcome of conflict, and so they struck out to reach areas controlled by Northern forces. This posed the question: Was this “contraband” to be treated as escaped property and returned to its “owner,” as the Fugitive Slave Act had required before the war?

Apart from the moral atrocity that this would represent, there was a practical dimension. Slaves were a critical resource in the Southern war effort. The Southern ruling class relied on them to provide the necessary labor to keep the economy and war effort going while a larger proportion of Southern white men fought. Black slaves did the backbreaking work of building fortifications for Southern forces.

Would Union officers return a valuable resource to help their enemies defeat them? Some racist officers proposed to do exactly this and even offered assistance in putting down slave uprisings–in keeping with the leanings of the pro-Democratic Northern command led by George McClellan.

But others reached different conclusions. Gen. Benjamin Butler–a Democrat and sympathizer with, in his words, “Southern rights, but not Southern wrongs”–learned that three slaves had escaped from building Confederate fortifications and reached the Union-controlled Fort Monroe, which he commanded.

Butler decided he would not return the escapees, but would consider them “contraband of war,” to be put to work as laborers–unpaid, until the Army later dictated a wage for the former slaves–for the Union Army. Within weeks, 1,000 fugitive slaves had escaped to the fort.

In Washington, Congress and the Lincoln administration reacted to such developments by passing the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, which gave a legal cover to Butler’s “contraband of war” reasoning. The Militia Act allowed Union officers to employ escaped slaves in the Northern war effort, and Congress banned slavery in the Western territories and enacted a plan to emancipate slaves in Washington itself–though it provided compensation to the slave owners.

Lincoln was still vacillating. He forced John Frémont to rescind his proclamation in Missouri after Congress passed the first Confiscation Act–arguing that this would appease “loyal” slave owners in the Border States and keep them in the Union. But he was under growing pressure from Black and white abolitionists in the North, from radicals in his own party–and from the trickle-turned-torrent of slaves escaping to the camps of the Union Army.

By the time the second Confiscation Act was passed by Congress in the summer of 1862, Lincoln was leaning toward taking another decisive step that would turn the Civil War into a war on slavery: the Emancipation Proclamation.

He was convinced by his Cabinet to wait until the Union Army had won a major victory–then still few and far between–so the order didn’t seem like an act of desperation. Lincoln got his chance in September 1862 when the Battle of Antietam in Maryland ended in a standoff, and the Confederate Army was forced to retreat back into Virginia.

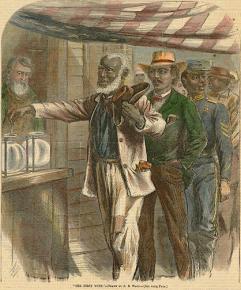

A few days after, Lincoln unveiled his proclamation, declaring that unless the Confederate states returned to the Union by the end of year, all slaves in those states would be declared “henceforth and forever free.” The Emancipation Proclamation also allowed the Northern armies to sign up Black men as soldiers.

The Emancipation Proclamation was, by intention, a half-measure. It left slavery intact in the Border States like Kentucky and Missouri–and even in areas of the South that were under the control of the Union Army. But the implications were clear to everyone: The Civil War was transformed from an attempt to put the pre-Civil War U.S. back together again to a war to destroy slavery. After January 1, 1863, Blacks would win their freedom wherever the Union Army advanced in the Confederate states.

Reflecting the sentiments of a large part of the Northern white population that abhorred slavery but was hesitant to stand for abolition, Lincoln himself was increasingly transformed by events themselves, like issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. By the end of the war, he was adamant against any suggestion that slavery should not be abolished.

This conversion was a vindication of Douglass’ belief that the Civil War would ultimately come to revolve around the abolition of slavery. And it was driven, most of all, by the determination of slaves to free themselves.

The effect of the Emancipation Proclamation was to finally make freedom for 4 million slaves the official war aim of the North. It turned the Northern military forces into an army of liberation, since wherever they advanced in the South, the promise of emancipation could be enforced. By the end of the war, Black soldiers were one-tenth of the ranks of the Union Army.

How that transformation unfolded during the next two years of the war will be the subject of what follows.

The Civil War becomes a Revolutionary War

By Donny Schraffenberger and Alan Maass

It was the summer of 1862, America’s Civil War had been underway for 16 months, and across the Atlantic Ocean, in the northern English city of Manchester, Frederick Engels was upset.

“Things are going wrong in America,” Engels fumed in a letter to a friend in London. He ticked off the latest military setbacks suffered by the North in the war against the Southern slave power–one blunder after another on the primary battleground of Virginia, a Confederate breakthrough with an offensive that drove across Tennessee and Kentucky to the banks of the Ohio River. Engels concluded that, against all odds, the North was on the edge of defeat:

[W]hat cowardice in government and Congress. They are afraid of conscription, of resolute financial steps, of attacks on slavery, of everything that is urgently necessary; they let everything dawdle along as it will, and if some semblance of a measure finally gets through Congress, the honorable Lincoln so hedges it with provisos that nothing is left of it.

This slackness, this collapsing like a punctured pig’s bladder, under the pressure of defeat that has annihilated an army, the strongest and best, and actually left Washington exposed, this total absence of any elasticity in the whole mass of the people–this proves to me that it is all up.

Engels’ London friend was equally pained by the victories of the South’s Confederacy, the states that had seceded from the Union to protect the institution of slavery. But Karl Marx disagreed about whether victory was at hand for the South.

“So far,” Marx wrote in August 1862, “we have only witnessed the first act of the Civil War–the constitutional waging of war. The second act, the revolutionary waging of war, is at hand.”

It was a prophetic comment. As Marx wrote those words, President Abraham Lincoln was preparing to announce the Emancipation Proclamation that would free the slaves in all the Southern states still in rebellion against the Union as of the end of the year. This was the primary confirmation of exactly what Marx predicted–that the Civil War would become a revolutionary war fought to destroy the institution of slavery, and with it, the power of the Southern ruling class.

The first steps toward that transformation came when the North gradually yielded to the self-activity of slaves who recognized the Union Army could become an army of liberation.

Before army officers and Northern political leaders were aware of the new weapon against the South that was being handed to them, slaves escaped to the Union Army’s lines wherever they were in reach. It became official policy to consider them “contraband of war.” Former slaves quickly became the backbone of the labor force in Union camps and fortifications.

Next came the recruitment of Black soldiers into the Union Army, which began in earnest after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. Once again, Lincoln had hesitated to take this more radical step, but he eventually yielded to the criticism of abolitionists like Frederick Douglass. Late in 1861, his newspaper Douglass’ Monthly had run an editorial decrying the government’s policy of “Fighting Rebels with Only One Hand”:

Why does the government reject the Negro? Is he not a man? Can he not wield a sword, fire a gun, march and countermarch, and obey orders like any other?…We do believe that such soldiers, if allowed to take up arms in defense of the Government, and made to feel that they are hereafter to be recognized as persons having rights, would set the highest example of order and general good behavior to their fellow soldiers, and in every way add to the national power…

[T]his is no time to fight with one hand, when both are needed;…this is no time to fight only with your white hand, and allow your black hand to remain tied.

When the Black regiments were finally formed, it was a bitter pill for former slaves that the Union Army paid them less than white soldiers and barred Blacks from being officers. The stakes were clearly far higher for Black soldiers. If they were to be captured by Confederate forces, they faced the certainty of being enslaved again, if they weren’t tortured and killed.

In spite of this, Blacks poured into the Union Army, driven by a determination given expression by, among many others, the Anglo-African newspaper:

Should we not, with two centuries of cruel wrong stirring our heart’s blood, be but too willing to embrace any chance to settle accounts with the slaveholders?…Why should we be alarmed at their threat of hanging us; do we intend to become their prisoners?…Can you ask any more than a chance to drive bayonet or bullet into the slaveholders’ hearts? Are you most anxious to be captains and colonels, or to extirpate these vipers from the face of the earth?

Some 50,000 Black men had enlisted in the Union Army and Navy by August 1863, and more than 200,000 would participate in their ranks by the war’s end–10 percent of the total. Their presence in the army of a government that a few years before had considered them property was the most explicit proof that the Union forces had become an army of liberation.

It was also evidence of the determination of Blacks to win their freedom. Nearly 40,000 Black soldiers died during the war, including at the hands of Confederate forces who wanted vengeance as the war turned against them.

In April 1864, Black soldiers were overwhelmed at Fort Pillow in Tennessee and massacred by white Confederate troops commanded by Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the millionaire slave trader and later leader of the Ku Klux Klan. Forrest gloried in his barbarism, in this passage later quoted by Union Army commander Gen. Ulysses Grant:

The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that Negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.

Forrest’s “hope” was dashed. The words “Remember Fort Pillow” became the battle cry for Black soldiers as they fought to destroy the Southern slave power.

The introduction of Black troops was, by itself, a qualitative transformation of the Union Army. But it also contributed to the radicalization of the rest of the army–the more than 2 million white soldiers, overwhelmingly from the laboring classes.

There was an abolitionist core to the Union Army from the start. Naturally, those most inspired by the cause of defeating the slaveocracy were the quickest to volunteer.

One little-talked-about chapter of Civil War history is the number of German-born immigrants who served in the war–they likewise made up about 10 percent of the Union Army. Many who came to the U.S. after the defeat of the European revolutions of 1848 were radicals fleeing repression once the old order was re-established. Like Marx and Engels in Europe, the German radicals recognized better than most the necessity of destroying slavery, not only for the basic ideals of bourgeois democracy to be realized, but for the infant working class movement in America to develop further.

But the majority of the Union Army didn’t start out as abolitionists. The army rank and file reflected the political sentiments of workers and small farmers throughout the North on the eve of the war. This included the pro-slavery appeasement of the Democratic Party, whose Northern wing, built around urban political machines, was always subservient to the Southern Democrats, who were the political rulers of the slaveocracy.

More commonplace was the attitude given political expression by the recently formed Republican Party–hostility to the economic and political power of the Southern slave system, but also, for many, hostility to the slave, as the historian W.E.B. Du Bois later described it.

The Civil War itself was the source for transforming this consciousness. Union soldiers were also motivated by the belief that they were the defending the democratic institutions and ideals created with the formation of the U.S.–and still, 90 years later, practically unknown in a Europe dominated by the old aristocratic order.

But as the soldiers saw firsthand the horrors of the slave system–and, over time, witnessed the determination of former slaves fighting for their liberation–more and more came to see the destruction of slavery as a central aim of the war.

Thus, one Illinois soldier wrote to his wife about how his unit confiscated horses and liberated hundreds of slaves in Tennessee: “Now what do you think of your husband degenerating from a conservative young Democrat to a horse stealer and a thief of slaves? So long as my flag is confronted by the hostile guns of slavery…I am as confirmed an abolitionist as ever was pelted with stale eggs.”

A Michigan sergeant went further in a letter to his wife:

The more I learn of the cursed institution of slavery, the more I feel willing to endure for its final destruction. After this war is over, this whole country will undergo a change for the better…Abolishing slavery will dignify labor; that fact, of itself, will revolutionize everything.

Not every soldier in the Union Army was won over to abolition, of course, but the balance shifted. This was as important to transforming the Civil War into a revolutionary war as the federal government’s political hardening and the change of the army’s general staff to get rid of pro-Democratic appeasers like McClellan.