Examining the persistent aggression and drive to conquer, the origins and dynamics of Roman imperialism.

By Dr. Neville Morley

Professor in Classics and Ancient History

University of Exeter

Introduction

It is said that cato contrived to drop a libyan fig in the middle of the senate, as he shook out the folds of his toga, and then, as the senators were admiring its size and beauty, said that the country where it grew was only three days’ sailing from rome. and in one thing he was even more savage, namely, in concluding his opinion on any question whatsoever with the words: ‘In my opinion, carthage must be destroyed’.

Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder, 27.1

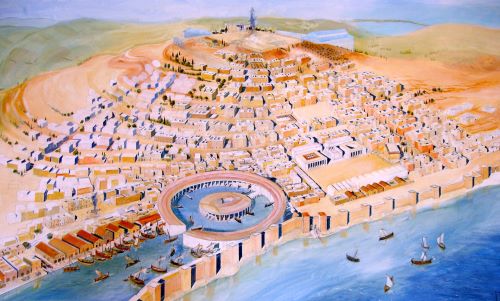

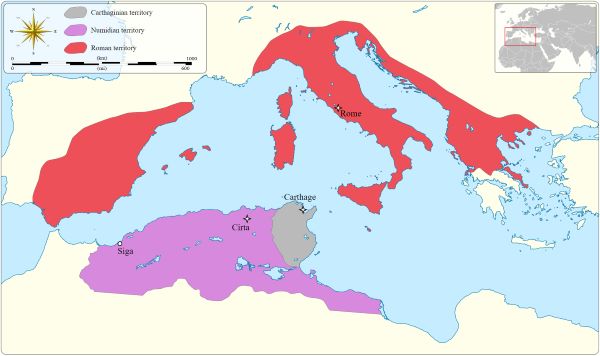

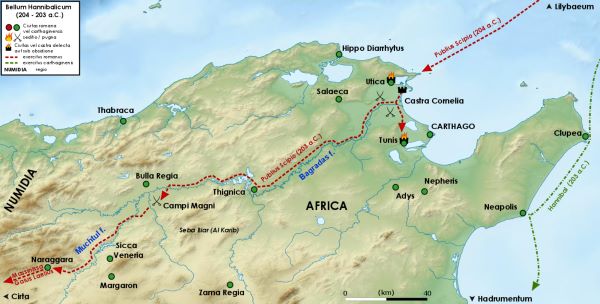

In 149 BCE, the Roman senate despatched an army to Africa: the city of Carthage had broken the terms of the peace treaty it had signed 60 years earlier, by starting a war with the neighbouring kingdom of Numidia without Roman permission, and therefore had to be punished.1 The Carthaginians, having failed to persuade the senate of the justice of their grievances against the Numidians (having, indeed, endured 60-odd years of unprovoked harassment, with Rome almost invariably deciding against them whenever they complained), sought to avert catastrophe by committing themselves to the faith of the Romans, an unconditional surrender of their whole territory and population. Their ambassadors were told that the proposal was acceptable, and that the Carthaginians would be granted their freedom and the possession of their whole territory, provided that they handed over 300 hostages, the sons of leading citizens, and obeyed the orders of the consuls who were commanding the army. Those unspecified orders, it transpired, were firstly to hand over all the weapons in the city; when that had been done, the Carthaginians were then ordered to abandon their city and establish a new settlement, at least ten miles from the sea.

The motive for this was transparent, as was made clear in the speech that the Greek historian Appian placed in the mouth of the Roman general: the absolute destruction of Carthage and the basis of its historic power.

If we were addressing you as enemies, people of Carthage, it would be necessary only to speak and then use force, but since this is a matter of the common good (somewhat of our own, and still more of yours), I have no objection to giving you the reasons, if you may thus be persuaded instead of being coerced. The sea reminds you of the dominion and power you once acquired by means of it. It prompts you to wrong-doing, and brings you to grief. By means of the sea you invaded Sicily and lost it again. Then you invaded Spain and were driven out of it. While a treaty was in force you plundered merchants on the sea, and ours especially, and in order to conceal the crime you threw them overboard, until finally you were caught at it and then gave us Sardinia by way of penalty. Thus you lost Sardinia also by means of this sea, which always begets a grasping disposition by the very facilities which it offers for gain.

Appian, The Punic Wars, 86

As Appian certainly assumed his readers knew, a Carthaginian or a Greek would have offered a very different account of the events of the previous century and a half. The two earlier Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage, 264–241 BCE and 218–201 BCE, could equally well be seen as the inevitable result of two major powers coming into direct contact with one another, each fearing the other. The first war broke out after a group of mercenaries seized control of Messana in Sicily, and appealed to both Rome and Carthage for assistance against the attempts of the powerful city of Syracuse to re-take it; the Carthaginians responded promptly by installing a garrison in Messana, whereupon the Romans feared that Carthaginian dominance of Sicily might threaten their own hegemony in Italy and belatedly decided to send their own forces. In Roman accounts, this was a purely defensive move, in response to a request for help; the eventual acquisition of Sicily and Sardinia as overseas territories was more or less an accidental outcome of their concern to defend justice and protect their own rights. A Carthaginian would have emphasised the way in which the upstart Italian power was clearly seeking to extend its reach into areas that were traditionally part of their own sphere of influence in the western Mediterranean, inciting proxy wars and finding pretexts for military intervention.

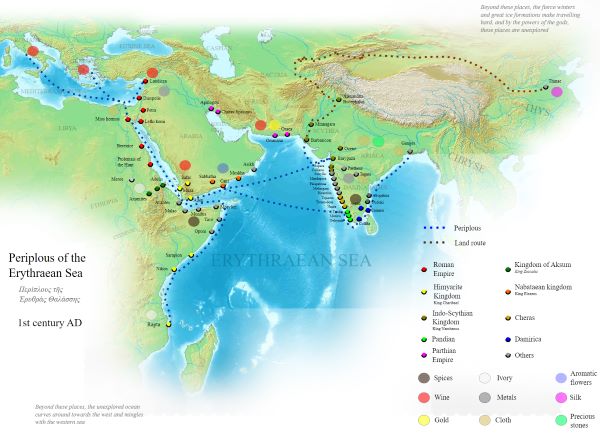

The outbreak of the Second Punic War offers an example. Carthage was above all a naval power, founded by the Phoenicians whose ships had traded across the Mediterranean for centuries; it sought to establish colonies in regions, such as southern Spain, which could supply timber and metal for its ships. During the uneasy peace after 241 BCE, it increased its hold on this area. The Roman response to the threat of a revival in their rival’s power was initially to make an agreement that the Carthaginians would remain south of the river Ebro; then, in the late 220s BCE, they established a relationship with the town of Saguntum, in the heart of that territory. With the promise of Roman protection, the Saguntines seized the opportunity to attack a neighbouring community and were punished by Hannibal, whereupon the Romans issued a blanket ultimatum: hand over the general or face war. The immediate consequences were disastrous for Rome, as Hannibal crossed the Alps and defeated a series of Roman generals in Italy, but the conclusion of the war was the reduction of Carthage from a world power to a minor state, forbidden to make war without Roman permission and required to pay a hefty indemnity to Rome for 60 years, while Rome added Spain to its overseas territories and now enjoyed undisputed mastery of the western Mediterranean.

Carthage remained a prosperous city, with rich agricultural resources and thriving trade connections; some Romans became convinced that, despite the loss of its empire, it would always be a threat to their security. According to the contemporary Greek historian Polybius (36.2), they simply waited for a suitable pretext that would persuade other nations that they acted honourably; the Carthaginians’ breach of the treaty conditions presented the opportunity to destroy their naval capacity, the basis of their old empire and of the future empire that the Romans feared or professed to fear, once and for all. Faced with the prospect of having their city destroyed in order to save it from itself, the Carthaginian response to the ultimatum was to fight; despite having given up their weapons, they successfully resisted the Roman army until 146 BCE. By then, the majority of the population had died of starvation or in battle; the remainder – numbers are notoriously unreliable in ancient sources, but the figure of 50,000 is cited – were sold into slavery, as was customary. The city burned for days and was then abandoned. The story that the fields were then sown with salt, to destroy their fertility and prevent anyone from living there, is a fabrication first encountered in the nineteenth century; the Romans, rather more practically, declared the territory to be public land, redistributed it to a mixture of local farmers and Italian settlers, and established it as the new province of Africa, paying a regular tribute to Rome.2

Approaching Roman Imperialism

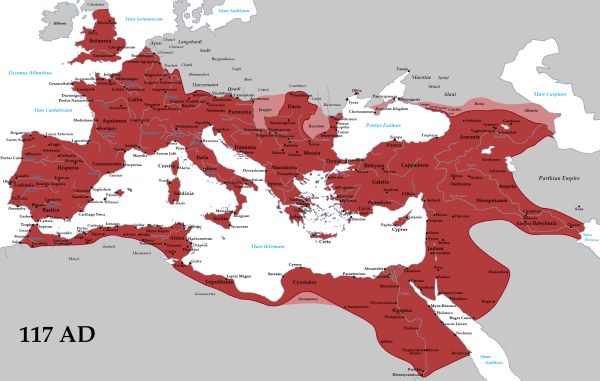

The Third Punic War was one of many fought by Rome in the course of its rise to the status of a world empire, from the conquest of its immediate neighbour Veii in 396 BCE, through the subjugation of the rival empires of Carthage, Macedon (168 BCE), Syria (63 BCE) and Egypt (30 BCE), to the invasion of Britain in 43 CE. While not every war resulted in the expansion of its power, let alone in the acquisition of new territory, the long-term trend was unmistakable. The obvious line of investigation is the nature of this persistent aggression and drive to conquer, the origins and dynamics of Roman imperialism. Surprisingly, however, a number of objections have been raised to thinking about the subject in these terms.

There is no Latin equivalent of ‘imperialism’.3 The word imperium, from which both ‘imperialism’ and ‘empire’ derive, referred originally to the power possessed by a Roman magistrate to command and expect obedience. It came, in time, to be extended to the power of the Roman people as a whole and then to that of the emperor, and took on a further meaning as the area within which Rome expected to exert its dominance without any opposition: its empire. However, the development of ideas about the nature of Rome’s overseas dominions followed long after they had actually been acquired, rather than preceding or influencing the process of conquest and annexation. Even in retrospect, Roman authors did not conceive of their city’s rise to dominance as the result of a policy, let alone as the result of greed or ambition, but rather as the reward of virtue and wise decision-making, along with the favour of the gods and the occasional piece of good fortune.4 According to Cicero, Rome fought only just wars undertaken in the face of provocation and in defence of its safety or its honour (for example, defending one of its allies), having always first offered the enemy an opportunity to make reparations instead. The acquisition of an empire was simply the result of Roman success in such virtuous endeavours, from its dominance of the league of local powers in Latium in the fourth century and triumph over Carthage in the third, to the acquisition of vast domains in Gaul and the eastern Mediterranean thereafter: ‘our people, by defending their allies, have gained dominion over the whole world’ (Republic, II.34).

The absence of any Roman term for a policy or ideology of expansion persuaded some modern historians to take such self-serving claims, and the rituals which the Romans undertook before a formal declaration of war – above all, the issuing of a non-negotiable ultimatum – entirely at face value.5 Roman behaviour was thus characterised as ‘defensive imperialism’, a view which also allowed Rome to be taken as a positive model and justification for empire-building. In sixteenth-century Spanish debates about the justice of the conquests in America, ‘the example of the Romans, whose rule over other peoples was just and legitimate’ was cited regularly in defence of Spanish imperialism, and this argument rested on the assertion that Rome had expanded ‘by taking over by law of war the cities and provinces of enemies from whom they had received an injury’.6 Centuries later, the Earl of Cromer, identifying various analogies between the Roman and British empires, noted:

That in proceeding from conquest to conquest each step in advance was in ancient, as it has been in modern, times accompanied by misgivings, and was often taken with a reluctance that was by no means feigned; that Rome, equally with the modern expansive powers, more especially Great Britain and Russia, was impelled onwards by the imperious and irresistible necessity of acquiring defensible frontiers; that the public opinion of the world scoffed 2,000 years ago, as it does now, at the alleged necessity; and that each onward move was attributed to an insatiable lust for extended dominion.7

Because Roman imperialism had, according to unimpeachable ancient sources, been defensive and reasonable, it was entirely credible to ignore the criticism and to believe that British imperialism might be the same.

Although few historians would now hold the view that Roman wars were invariably or even frequently defensive, the use of the term ‘imperialism’ in the analysis of Roman expansion remains controversial; it may be mentioned only to be rejected, or omitted altogether, even if the author is happy to attribute less than noble motives to the Romans.8 The reasons for this vary and are not always stated. Some historians understand ‘imperialism’ strictly as an ideology of expansionism that must be consciously held and explicitly proclaimed by the conquering state, conditions which clearly did not apply to Rome. For others, the modern connotations of the term, pejorative and highly political, imply that its application to the ancient world will inevitably result in anachronism. There is a long-standing tradition in ancient history of rejecting all modern concepts and theories as misleading, claiming that they force the reality of the past into conformity with modern assumptions and expectations, and ignore its specificity and detail in favour of broad generalisations.9 To think about Roman history in terms of ‘imperialism’ is, according to this argument, to see it solely in terms of the dynamics of modern empires, driven by capitalist over-accumulation, or nationalism and racism, or competition between modern states. Rather, we should focus on the detail of events – the reasons why the Romans went to war in individual cases and the outcomes of those wars – without any suggestion that this was a coherent or directed process and without recourse to modern concepts.

If, therefore, we hope to understand the groping, stumbling, accidental expansion of Rome, we must rid ourselves of anachronistic generalizations and ‘remote causes’ and look instead for the specific accidents that led the nation unwittingly from one contest to another until, to her own surprise, Rome was mistress of the Mediterranean.10

The flaws in such arguments are obvious. The fact that Roman expansionism was not an explicit policy clearly does not mean that the growth of the empire was entirely accidental; on the contrary, the fact that the Romans consistently failed to get on with their neighbours, and as a result steadily accumulated more territory, suggests that it was anything but. Doing away with modern terms of analysis does not enable historians to escape from the way that, consciously or subconsciously, their interpretations are inevitably shaped by contemporary conceptions and concerns. It is certainly the case that ‘imperialism’ has political connotations, generally but not invariably negative, and that applying the term to Rome is intended to establish links between past and present – but an insistence on avoiding the word, refusing to draw any connections between comparable historical events and denying the existence of the phenomenon can be equally political, offering an alibi for Roman imperialism and for imperialism in general. The idea of an ‘accidental’ empire, acquired ‘in a fit of absence of mind’ or as the entirely unforeseen consequence of entirely reasonable actions, was just as useful to apologists for the British Empire as the idea of an empire acquired in justifiable self-defence.11

The Roman Empire was founded upon military considerations… This does not mean that their Empire was purely the outcome of deliberate conquest and annexation on a preconceived plan. They were drawn on in the path of Empire, as we have been drawn on, by force of circumstances.12

At the same time, of course, there are certainly risks in taking too simplistic or monolithic a view of ‘imperialism’, obscuring all historical difference; in many important respects, the process of Roman expansion was significantly different from that of the Spanish or British, or late-twentieth-century United States hegemony. This may be a concern not only for historians but also for studies of contemporary imperialism. Writers in the Marxist tradition have long been aware of the dangers of understanding ‘imperialism’ in excessively general, transhistorical terms, as a ‘policy of conquest in general’, defined above all by its past historical manifestations and thus obscuring the specific nature, roots and dynamics of the modern phenomenon. As Nikolai Bukharin argued,

From this point of view one can speak with equal right of Alexander the Macedonian’s and the Spanish conquerors’ imperialism, of the imperialism of Carthage and Ivan III, of ancient Rome and modern America, of Napoleon and Hindenburg. Simple as this theory may be, it is absolutely untrue. It is untrue because it ‘explains’ everything, i.e. it explains absolutely nothing!13

‘Publicists and scholars attempt to paint modern imperialism as something akin to the policies of the heroes of antiquity with their “imperium”’, ignoring the fundamental differences between ancient slave society and modern capitalism.14 The theory of imperialism developed by J.A. Schumpeter, which sees it as an atavistic survival of the aggression and lust for conquest of primitive warrior states, exemplifies one of the problems with this approach by obscuring the connection between modern economic structures and modern imperialism.15 Another is the pseudo-Darwinian idea that aggression and the drive to maximise reproductive opportunities, resulting in empire, are universal traits of human behaviour and hence can never be changed.16 However, the solution is not to restrict the term ‘imperialism’ to a specific and strictly modern phenomenon, but rather to strike a balance between sameness and difference, with regard both to the variations between different historical imperialisms and to the contexts within which they developed. Lenin’s account of imperialism, for all its indebtedness to Bukharin, offers a more moderate line in this regard:

Colonial policy and imperialism existed before this latest stage of capitalism, and even before capitalism. Rome, founded on slavery, pursued a colonial policy and practised imperialism. But ‘general’ disquisitions on imperialism, which ignore, or put into the background, the fundamental difference between social-economic systems, inevitably degenerate into the most vapid banality or bragging, like the comparison ‘Greater Rome and Greater Britain’.17

Similarly, understanding the overall process of Roman expansion is a matter of balancing generalisations with specifics: drawing on modern theories as a source of ideas about how societies work and therefore how the ancient evidence might (rather than must) be interpreted, and modifying the understanding of ‘imperialism’ as a more general historical phenomenon in the light of the Roman experience.

The study of Roman imperialism seeks to identify patterns and consistencies in the mass of detail and individual events, and to evaluate their significance. Inevitably it involves questions of how far, and in what respect, a particular episode might be seen as typical or representative. The events of the Third Punic War, for example, fit very poorly with the idea that Roman imperialism was defensive, but they are also difficult to reconcile with any theory that sees Roman expansion as fully rational; on the contrary, the main motive (epitomised by Cato’s fig-dropping performance) appears to be an entirely irrational fear and hatred of the old enemy Carthage, even after it had been thoroughly defeated and stripped of any significant power. The episode might, then, be seen as an aberration (and the choice of it as the opening example for this chapter regarded as tendentious, designed to present the Roman Empire in the worst possible light); alternatively it might be claimed, by a theory of imperialism such as Schumpeter’s, as a perfect example of the behaviour of ancient states, even if their aggressive instincts were normally better concealed behind pretexts and claims to be acting justly.

Neither of these positions is entirely convincing. Rome’s past history of bitter conflict with Carthage, and above all the legacy of Hannibal’s invasion of Italy, meant that this was in some respects a special case; however, it was not entirely sui generis, and any theory of Roman imperialism needs to be able to account for this war as well as other, more straightforward episodes. Three points are particularly worth noting. The first is the complexity of decision-making in Rome, and hence the difficulty for modern historians in divining the motives behind decisions. A straightforward narrative of events in which ‘the senate decided’ or ‘the Romans resolved’ conceals the extent to which there was debate, perhaps serious debate, about the decision to undertake any particular war, and about whether or not to annex a particular territory after victory. In the case of the final war on Carthage we find an apparent conflict between the assertions of Greek historians like Polybius and Appian that ‘the senate’ had long since resolved to make war on Carthage and was simply waiting for a pretext, and the account of Cato’s role in obsessively promoting an anti-Carthaginian policy at every opportunity. At the very least there seems to be a disagreement about timing and tactics – Polybius suggested that ‘their disputes with each other about the effect on foreign opinion very nearly made them desist from going to war’ (36.2) – but perhaps there was disagreement about more fundamental matters of strategy. The issue of Roman motivation is complicated further by the complexity of its political system, with different elements having different powers and remits, each being able on occasion to press the others into supporting their wishes:

Now the elements by which the Roman constitution was controlled were three in number, all of which I have mentioned before, and all the aspects of the administration were, taken separately, so fairly and so suitably ordered and regulated through the agency of these three elements that it was impossible even for the Romans themselves to declare with certainty whether the whole system was an aristocracy, a democracy or a monarchy. In fact it was quite natural that this should be so, for if we were to fix our eyes only on the power of the consuls, the constitution might give the impression of being completely monarchical and royal; if we confined our attention to the senate it would seem to be aristocratic; and if we looked at the power of the people it would appear to be a clear example of a democracy.

Polybius, Histories, 6.11.11–12

It should be noted further that while ‘the senate’ (or ‘the Roman elite’) can often be thought of as a unified bloc dedicated to the maintenance of its own power and interests against the mass of the population, it was in practice riven with factions and rivalries. Insofar as the senate showing any signs of coherent organisation, rather than simply being a collection of individuals focused on their own interests, the dividing lines were between ill-defined groups connected by ties of kinship, friendship or advantage, not between parties united around beliefs or political programmes. The study of Roman imperialism is not the study of the explicit and univocal policy of a government or ruler, or of their concealed but fully conscious ambitions, but of the structures that shaped the decisions taken by the individuals in the senate, the magistrates and the people of Rome over the course of centuries. The cumulative result is clear enough, but it is entirely plausible that it developed from a combination of different motives and interests, irrational as well as rational, and that the eloquence of an individual speaker might at times be as significant in determining the course of events as the interests of a larger group. Under the Principate, the decision-making process became simpler, resting on the judgement or whim of an individual emperor under the influence of different advisors – and it is striking that there is significantly less disagreement amongst historians about the nature of Roman rule over the Empire than about the process by which the bulk of the Empire was acquired.

The second significant point is the possibility that Roman imperialism changed over time, and not simply with the end of large-scale expansionism under Augustus. Certainly the Third Punic War was interpreted by some contemporary Greeks as representing a change in approach; Polybius reports them as ‘saying that far from maintaining the principles by which they [the Romans] had won their supremacy, they were little by little deserting it for a lust of domination like that of Athens and Sparta’ (37.1). Some Roman authors, looking back from the political disorder of the first century BCE, saw the war as the moment when they had lost the favour of the gods by acting unjustly. In more material terms, the success of Roman imperialism changed the conditions under which future wars took place. Their armies came to operate over increasingly large areas and different sorts of terrain, creating new problems of logistics, communication and the supervision of generals; they encountered new kinds of opponents, from the city states of southern Italy, Sicily and Greece to the empires of Carthage and Macedon, and the disordered tribes of Spain, Gaul and Germany. At the same time Rome itself changed, and thus the context of decision-making: the influx of wealth altered the workings of the political system and the balance between its different components, while the relationship between Rome and her allies, and between the citizen population and the army, were affected by dramatic changes in the economy and society of Italy as it became the centre of a Mediterranean-wide empire.18 There were sufficient continuities in the structures that shaped Roman imperialism to continue to think of it as a single phenomenon, as will be discussed below, but it was never entirely uniform.

The third point relates to our sources. It is not simply that, as in the history of many other empires, we have to rely primarily on the accounts of the imperialists themselves with scarcely anything from the perspective of the conquered and colonised; in the case of the Roman Empire we have a significant number of important accounts from Greek writers, who reached an accommodation with Rome early on but nevertheless do offer an alternative perspective.19 Rather, it is the fact that most accounts of the growth of Roman power were written in retrospect, from the perspective of the crises of the last century of the Republic or from the vantage point of the new monarchical order established after the civil wars by Augustus. Roman histories of their Empire are not simply or invariably self-serving and justificatory – indeed, they offer some remarkable denunciations of Roman imperialism that have been quoted by opponents of empire ever since – but they do naturally interpret the past according to present concerns and in the service of present needs. Sallust’s account of Roman imperialism before and after the defeat of Carthage, written around 42 BCE, offers an example:

And so the power of the republic increased through diligence and justice. Powerful kings were vanquished, savage tribes and huge nations were brought down; and when Carthage, Rome’s imperial rival, had been destroyed, every land and sea lay open to Rome. It was then that fortune turned unkind and confounded all of Rome’s enterprises. To the men who had so easily endured toil and peril, anxiety and adversity, the leisure and riches which are generally regarded as so desirable proved a burden and a curse. Growing avarice, and the lust for power which followed it, gave birth to every kind of evil. Avarice destroyed honour, integrity and every other virtue, and instead taught men to be proud and cruel, to neglect religion and to hold nothing too sacred to sell.

Sallust, The War Against Catiline, 10

Clearly this cannot be taken at face value. First-century accounts, both of the past and of contemporary imperialism, were fully implicated in the struggle for power and the control of meaning as the republic tottered; Caesar’s reports back to Rome of his own activities in Gaul are simply the most extreme example. Later histories, written under the stultifying influence of powerful and temperamental monarchs, were similarly influenced or distorted. To uncover the reality of Roman imperialism, it is necessary to confront not only the way that Rome was mythologised by later societies but also the myths and polemics that the Romans developed themselves.

Motivation and Ideology

One approach to understanding Roman imperialism is to focus on the factors that inclined the Romans to make war: not the specific tactical or political considerations that affected an individual decision, but the general conceptions and ideological structures that made it more likely than not, especially under the Middle Republic (up to the mid second century BCE), that Rome would despatch an army in any given year. As discussed above, the nature of the decision-making process in Rome means that the reasons behind any individual decision were almost certainly mixed, but, at least for the elite, it is possible to identify a number of consistent factors shaping their choices.20

The first was an obsessive concern for security. It is not necessary to accept the Romans’ claims that all (or nearly all) their wars were fought in self-defence to recognise that these claims were not simply a sop to public opinion, whether in Rome (where the people might be reluctant to fight except in defence of their home) or across the Mediterranean (where trust in Rome’s good faith could be as important as fear of Roman power in keeping allies and neutrals in line). The early years of Roman history established a mindset of prickly defensiveness and suspicion: the fifth century had been a desperate struggle to resist the attacks of powerful neighbours; the beginning of the fourth century saw Celtic raids into Italy and the sack of Rome itself around 386 BCE; and the third century brought Pyrrhus of Epirus and a mercenary army, invited across from Greece by the city of Tarentum to check Roman power, and then the Carthaginians. The Romans had a strong sense of their own past, kept alive by handing down stories of their heroic ancestors (and, according to some historians, through the regular performance of historical plays) long before they began to write formal history.21 They internalised not only the values of the past but also its sense of being surrounded by a hostile world; and, of course, as their success in repelling one enemy brought them increased power and wealth and thus persuaded others of the need to check their growing power, the world frequently confirmed their suspicions.22 Any city or nation that was not under firm Roman control, whether informal or formal, was a potential threat, if not in itself then because it might ally with a rival power. Rome did become less belligerent (at least in terms of the number of wars) after the Second Punic War because it no longer faced an enemy that could menace its own existence; but, as the final destruction of Carthage shows, the senate could still be persuaded to act aggressively in the supposed interests of Roman security.

One element in Roman decision-making, therefore, was a genuine – if sometimes entirely groundless – fear of the consequences if they failed to intervene in a region perceived as troublesome. However, the fact that we hear about Roman generals being criticised for suspected war-mongering makes it clear that there were other factors which made war seem an attractive as well as necessary policy to members of the elite. The most obvious was gain.23 Successful war-making and conquest were generally profitable for all concerned: slaves and booty were seized in the immediate aftermath of victory (the defeat of Macedon in 167 BCE brought in 120 million sesterces of booty); countries that were allowed to remain independent might be required to pay large indemnities to Rome, while those that were annexed as provinces had to pay regular tribute in cash or goods (Macedonia yielded an annual revenue of 2.4 million sesterces). Large areas of land could be confiscated and redistributed to Roman settlers and members of the elite, while assets like mines and quarries were taken into Roman ownership (the Spanish silver mines produced 36.5 million sesterces every year). These profits were spread throughout Roman society: not only amongst the victorious general and his troops, the rapacious governor and the societies of tax-collectors, but Roman society as a whole, with large-scale building projects and distributions of grain funded from the proceeds of conquest. Of course, not all conquests were equally profitable or could compare with the enormous riches captured from the empires of the East; if a strict cost–benefit analysis were applied, it is highly arguable whether the efforts to conquer and subdue some regions were really worth it (the income from the Spanish silver mines, for example, barely covered the costs of pacifying the region).24 But the Romans did not apply cost–benefit analyses in a consistent manner: the military resources were available, in the form of the duty of citizens to serve in the army and the requirement on Rome’s Italian allies to supply troops, so that one might almost speak of an opportunity cost if these forces were not employed productively in war in a given year.25 The expedition into Dalmatia in 156 BCE, on the grounds that the army needed exercise, was an extreme example (there had also been raids across the frontier and insults as provocation), but it is revealing of the Romans’ casual attitude towards the deployment of their forces when they were not confronted with a really serious threat.26 The costs and benefits of making war were not equally shared, so that the consuls had little reason to hesitate even if a majority in the senate was reluctant to take on further commitments; further, reliable information was inevitably in short supply, so that rumours of a country’s wealth might be sufficient to persuade waverers. This is not to say that all, or even any, decisions to go to war were made solely for reasons of profit, but they were always made with an awareness of the likely profitability of conquest for those involved.

Discussion of the material motivation for Roman war-making sometimes becomes conflated with modern ideas of ‘economic imperialism’, in which overseas interventions are seen to be driven by national economic interests or by special interest groups lobbying and bribing the decision-makers. There is little evidence to suggest that this was a significant factor in antiquity.27 The Romans did not conceptualise ‘the economy’ as a significant sector of society, and certainly did not regard it as part of the role of the state to promote trade or economic growth.28 On a few occasions the stated grounds for military intervention were to protect Roman or Italian traders from harassment by pirates (for example, in Illyria in 229 BCE; Polybius, 2.8.3), but this seems to be a matter of defending citizens as a matter of national pride and status, and of responding to a threat to Roman security and dominance, rather than protecting trade per se. The publicani, the groups of businessmen who bought up contracts to supply the army, collect tribute and manage state assets, are known on occasion to have lobbied the senate in favour of military action, but the chief example is their call for Macedonia to be annexed in 167 BCE to gain control of its mines, a call which was ignored.29 It is possible that other, more successful attempts at persuasion may have remained unrecorded, but it is important to remember that any such attempt had to win over not a leader or a party but a large number of individual senators. In practical terms, it was impossible to persuade the senate to agree to a policy that a majority of its members did not believe was in their own best interests.

From the perspective of the individual member of the Roman elite, financial profit was not the only possible gain from successful military action; there was also glory.30 Young aristocratic men were inculcated with an ideology of public service, encouraged to devote their lives to outdoing both their contemporaries and their predecessors. In the words that Cicero placed in the mouth of Scipio Africanus, ‘all those who have preserved, aided or enlarged their fatherland have a special place prepared for them in the heavens’ (Republic, 6.13).

As soon as the young men could endure the hardships of war, they were taught a soldier’s duties in camp under a vigorous discipline, and they took more pleasure in handsome arms and war horses than in harlots and revelry. To such men consequently no labour was unfamiliar, no region too rough or too steep, no armed enemy was terrible; courage was everything. Their hardest struggle was with each other; each man strove to be the first to strike down the foe, to scale a wall, to be seen by all while doing such a deed. This they considered virtue, this fair fame and high nobility.

Sallust, The War Against Catiline, 7.4–6

Sallust’s account of the virtuous Republic of the past is driven by the contrast with the ‘decadent’ Republic of his own time, dominated in his opinion by avarice and luxury; it may not be historically accurate, therefore, but it does clearly express the ideals of the Roman elite, the values which they believed should determine their behaviour. The Roman noble was trained in warfare and in military values from an early age; his public career began as a military tribune and, as he proceeded through the cursus honorum, the ladder of official positions, his terms of office as a magistrate and a member of the senate were interspersed with further periods of military service. War provided opportunities for glory, and a basis for the greater glory of attaining the higher magistracies; an impressive war record was one of the most important qualities that an aristocrat could display to persuade the people to vote for his candidacy. In turn, the consulship entailed command of an army and the possibility – if Rome went to war – of gaining the highest honour of a triumph. Such glory was not essential for political success – by the second century, at any rate, the example of Cato shows that it was possible to build a career on the basis of civilian attributes like oratory – but it remained central to Roman ideology even after the system of competition for office had collapsed. A weak emperor like Claudius, dependent on the continuing support of the military, would make war in order to establish his credentials as the head of the Roman Empire and the army’s commander in chief. Other emperors sought to match or out-do their predecessors and, just as importantly, to limit the opportunities for potential rivals to win glory by permitting only members of the imperial clan to celebrate triumphs.31

This militarised value system and atmosphere of fierce competition for honour and status would clearly prompt any consul to adopt a bellicose attitude during his term of office, seeking to make the best advantage of the single year in which he had command of an army (while perhaps picking and choosing possible theatres of operations; there was always more prestige in bringing a war to a close than in starting one for a rival to conclude). The fact that military achievements clearly did carry weight with voters implies that the people shared the elite view that the best leaders were the most successful generals. There is almost no direct evidence for the attitudes of the masses towards war, except that Rome experienced little difficulty in recruiting troops for most of its wars before the second century. It was a taken-for-granted duty of a Roman citizen to serve in the militia; Roman society (including the way that citizens were organised into groups for voting) was structured like a military camp, and so we might imagine that the ideology of war as normal and praiseworthy was pervasive. The senate was the obvious arena for more mixed opinions: on the one hand, senators might be reluctant to grant a rival the opportunity for glory; on the other, they had the same unquestioning belief in the virtues of military activity and a concern for the reputation of Rome itself – the favour of the gods might depend on maintaining faith with one’s allies, even those acquired only recently for solely tactical purposes, while every victory added to the prestige and standing of Rome even more than it did to that of the individual general.

International Relations

The focus on motivation and the ideology that underpinned it suggests reasons why the Romans were generally inclined to make war on their neighbours, while the need to balance different ends – to prevent an individual’s drive for glory and profit from compromising Rome’s security, for example – and, above all, the complex decision-making process show why their policy was never wholly consistent. However, this ‘psychological’ approach to understanding imperialism has a number of problems and limitations. It takes the Romans’ mindset and ideology entirely for granted – an assumption not too far removed from Schumpeter’s belief in the universality of innate primitive aggression – rather than considering the possibility that a militarised ideology might be the product rather than the cause of a tradition of violent relations with the rest of the world. Furthermore, this approach focuses solely on decisions taken at the centre; imperialism is seen as a directed, conscious process in which the conquering power imposes itself on other nations. Essentially, however far it expresses or implies criticism of their actions, this ‘metrocentric’ approach adopts wholesale the perspective of the conqueror and coloniser.32

Some recent studies of modern imperialism have therefore sought to focus instead on the imperial periphery, the regions outside the empire.33 The aim is to understand the conditions that make a country vulnerable to external interference, whether or not that results in formal annexation (this approach can also be productive in understanding the fate of regions in the post-colonial era, precisely because it focuses on the state of ‘native society’ rather than on the aims and actions of the conquerors).34 Applied to the Roman period, a focus on the periphery emphasises the wide variety of situations faced by the Romans in the course of their expansion – from established empires such as Carthage and Egypt; to the mosaic of small, disunited statelets in Greece; to the pre-state, tribal societies of Spain and Gaul.35 It was not just that these polities had to be handled in different ways and represented different levels of threat; in many cases, conditions at the periphery created opportunities for Rome to intervene, or left them with little choice but to get involved. Rivalries amongst the Greek states and their fear of Macedon led them to seek the protection of an alliance with a greater power; the Romans sought to protect their interests through strategic alliances with neighbouring states, but could then find themselves pulled into local affairs, or in conflict with another of the major powers, as a result.

The same happened in Gaul in the first century BCE when one tribe, the Helvetii, sought to pass through the territory of another tribe that had long-standing ties with the Romans and who called on them for help (Caesar, Gallic War, 1.11). Of course, the Romans might in theory refuse a request for assistance, but that would damage their credibility with other allies and create an impression of weakness in the face of potential enemies. Having seen off the Helvetii, Caesar was then approached by representatives of a confederation of Gallic tribes and asked to intervene against the German Ariovistus who had established dominion over an area of eastern Gaul.

The most important consideration was the fact that the Aedui, who had frequently been styled by the senate ‘Brothers and Kinsmen of the Roman People’ were enslaved and held subject by the Germans, and that Aeduan hostages were in the hands of Ariovistus and the Sequani, which, considering the mighty power of Rome, Caesar regarded as a disgrace to himself and his country. Furthermore, if the Germans gradually formed a habit of crossing the Rhine and entering Gaul in large numbers, he saw how dangerous it would be for the Romans… Moreover, Ariovistus personally had behaved with quite intolerable arrogance and pride.

Gallic War, 1.33

The result was the extension of Roman dominance over a large area of Gaul, provoking the northern tribes into gathering their forces and thus providing grounds for further war and conquest. It is an important reminder that, while some groups on the periphery actively invited Roman intervention, and the disordered or disunited state of some peripheral societies made them ripe for conquest, the Romans were rarely slow to recognise the material benefits of maintaining Rome’s reputation for aiding its allies. Recognition that conquered nations and peoples were not always wholly passive victims of Roman aggression can too easily shade into a new version of the ‘defensive imperialism’ thesis, an apology for imperialism. Empire comes to be justified as the source of order in an anarchic world, saving weak and inferior societies from themselves: ‘the growth of Roman dominion was the necessary and natural advance of a genuine governing nation in a world politically disordered, like the advance of the English in India’.36 Similar rhetoric has been brought forward in recent decades to support an interventionist United States foreign policy, presented as a response to calls for assistance and liberation from smaller nations oppressed by their neighbours or rulers, and as the means of establishing the necessary conditions of peace and security for the benign processes of globalization.37

An alternative approach seeks to interpret imperialism in terms of the doctrines of the realist school of international relations theory.38 States, it is assumed, seek always to maximise their power as a means of self-preservation in the face of other power-maximising states within an anarchic and highly competitive world. War is ubiquitous as the normal means of resolving conflicts of interest between states, and a state which is successful in war naturally seeks to take full advantage of this to bolster its position. Empire, therefore, is simply the natural result of a state adapting especially well to its hostile environment, or possessing some material advantage over its rivals. The ancient Mediterranean was undoubtedly anarchic, with no international law, poor and slow communications and no means of enforcing the few rules of conduct between states besides fear of the gods; war was indeed ubiquitous, and it is clear that Rome’s militaristic culture was shaped by this environment – as were the cultures of many other states. As discussed above, it is clear that concerns for security and fear of a rival gaining advantage were crucial influences on the decision of both Carthage and Rome to intervene in Sicily in 264 BCE, and other episodes, especially Rome’s interactions with the empires of Macedon and Syria in the East, can be interpreted similarly. However, the conception of state motivation in realist theory is unhelpfully narrow, ignoring the complexity of the decision-making process and the significance of different interests and interest groups even in the modern world, let alone in Rome.39 The theory tends to take for granted the existence of modern nation-states as the actors in international relations, whereas the ‘states’ of classical antiquity were more loosely structured and far more disparate in nature, and hence inclined to follow different strategies for power maximisation – to say nothing of those areas which had at best proto-state structures. In important respects, Rome’s environment was more anarchic, complex and unpredictable than that assumed by realist theory, so that its assumptions about the nature of relations between power-maximising, security-obsessed states offer at best only a partial, and very general, guide to the dynamics of Roman imperialism.

The Rise of Fall of the Military-Political-Agricultural Complex

The international relations approach, whatever its questionable aspects, places an important emphasis on the role of systems and constraints in determining the course of historical events. Roman imperialists were never in the position of making entirely free decisions; their choices were always conditioned, partly by external circumstances and partly by the workings of their own society. Whether or not this was entirely a response to the hostility of their environment, war was internalised to the extent of being not merely an expectation and an ideal for Rome’s elite but a requirement for the proper functioning of society. There were two different, interdependent processes in Rome which drove the acquisition of empire and the defeat of all significant external threats. In due course, as a result of their very success, they also became a source of disruption and social breakdown, bringing about the collapse of the Roman political system, its refoundation as an autocracy and significant changes in external behaviour, as the price of retaining the Empire.

The first process has already been mentioned: the cycle of accumulation of the Roman elite.40 The ultimate goal was family power and prestige: material resources were accumulated as a means of gaining status and, especially, of gaining the opportunity for military glory by holding political office; political and military power were used as a means of accumulating material resources. There was no logical end to the cycle, no point at which a family or individual might conclude that they had amassed sufficient wealth and honours, only an incessant comparison with the successes of other families and individuals in accumulation. However, the success of Roman imperialism and the stability of Roman society, which created these opportunities for elite aggrandisement, depended on ensuring a balance between competition and solidarity, and thus on imposing a certain number of rules on the contest. The great fear was that one individual might gain an excess of power and seek to take over the game altogether, so the system incorporated a range of checks: the short duration of magistracies; limits on the number of terms; set periods between one magistracy and the next; the principle of collegiality, so that the actions of every magistrate were subject to the veto of a colleague with equal powers and status; laws to try to control the scale of resources that could be expended in competition for office; and the informal sanctions at the disposal of the senate, such as threatening to withhold honours from successful generals if they over-stepped the boundaries. The system sought to ensure that individual and state interests reinforced one another to the benefit of both; it encouraged fierce competition, in the service of the power of Rome as a whole, not least through the way that the most able were forced to exert themselves ever harder as they climbed up the cursus honorum. Every year, 20 quaestors (the lowest level of magistrate) were elected; in due course, the survivors of those 20 would be competing with one another, and with older senators, for just two consulships.41

The cycle of elite accumulation drove Rome’s tendency to make war; however, it would never have endured or even come into existence without the support of a second process that made Rome’s sustained military activities possible.42 This process operated within Roman and Italian society as a whole, and might be termed a cycle of sustainability; its effect was that war became embedded in the economy and society. For centuries Roman wars were fought with citizen militias, both Roman citizens and the troops supplied by the allies, founded on the sort of peasant patriarch whose image dominated later Roman literature as the essence of true Romanness, fighting for the most part during the quiet agricultural season. War served as a means for the profit of the elite without alienating the masses; taxes were kept low, partly because the state provided only very limited services and partly because the system was organised around military service as an alternative means of surplus appropriation.43 The peasants benefited both directly (from booty) and indirectly (from low taxes and public amenities) as a result of successful conquest; war could therefore be used as a distraction and an outlet for the energies of the masses, which might otherwise have been directed against the dominance of the elite – certainly this was how some ancient sources presented it. Even when military service became more arduous with the expansion of the Empire, because of year-round garrison duties, long wars and distant overseas commitments, it remained manageable because of the way that the life-cycle of the peasant family worked; a farm could cope with the absence of a son for a period of years, and benefited, or at least was compensated, from the additional income from wages and booty.

For the individual household, of course, it was a serious problem if their son was killed or crippled, especially if he was the only heir. As far as Italian society as a whole was concerned, however, the effort was sustainable; Italy benefited from the influx of revenue as well as from the ‘demographic sink’ effect because war casualties kept population growth low, and thus ensured that living standards were maintained, or possibly even improved, without any increase in productivity. However, this meant that regular wars became a necessity; without the flow of tribute and the draining of excess manpower, the Italian population might have risen relative to the available resources, leading to widespread impoverishment and the possibility of rebellion against those who controlled the lion’s share of social wealth. That is not to say that the Roman elite perceived the situation in these terms or were conscious of its underlying dynamic; they simply took advantage of the willingness of their citizens to fight and the availability of troops from their Italian allies. Behind the scenes, Italian society had become geared to regular war, both culturally and economically; Rome rarely had problems in finding soldiers for its conflicts, even in the periods of more or less constant war up to the second century, so there was no constraint on the drive to accumulation of the elite.44

For centuries, Roman imperial expansion was driven by the interaction and reciprocal reinforcement of these two cycles. By the middle of the second century, however, problems were beginning to emerge, largely as a result of the system’s success. The conquest of the wealthy east, above all, brought about a dramatic increase in the profits to be made from political offices; so did the competition for them, and so too the amount of expenditure now required to have a reasonable chance of getting elected. Family resources were often no longer sufficient; Roman notables began to speculate on the potential rewards of office, and their willingness to spend heavily on gaining supporters and bribing the electorate then created the necessity for them either to launch a grand military campaign or to despoil their province in order to pay off the debts they had accumulated. It is clear that many senators chose to opt out of this increasingly uncontrolled competition, content to reach the lowest tier of the cursus honorum and to concentrate on accumulation through exploitation of existing resources rather than active dispossession. However, a small number of individuals whose speculations in power had paid off became ever more powerful, able to dictate to the senate, demand the ratification of their actions even if technically illegal (for example, Pompey’s conquests in the East and the administrative arrangements he put in place without any consultation) and lead armies against other Roman citizens. Each of these men was fearful of the power of the others, alternating between uneasy alliances with one another against the attempts of members of the senate to place restrictions on their power (the obvious example is the ‘first triumvirate’, the pact between Caesar, Pompey and Crassus in 60 BCE) and seeking to counter one another’s ambitions. Both Pompey and Caesar became immensely wealthy as the result of their conquests, but it was impossible for them to leave the competition and give up their armies for fear of losing everything if prosecuted by their enemies. The interests of the state were now firmly subordinated to those of a few powerful individuals, driven to establish their position through military endeavour – but those individuals were equally trapped in the dynamics of the cycle of conquest.

Meanwhile, imperial success brought about far-reaching changes in the economy of Italy, with the growth of the city of Rome and other major urban centres and the establishment of slave-run, market-orientated villas in central Italy.45 New economic opportunities appeared, subsidised by the proceeds of empire, but peasant families whose sons were overseas – or who had been killed in battle – were less able to take advantage of them or to afford the investment that would take them to a higher level of prosperity.46 Furthermore, there was now fierce competition for the most fertile and well-situated land, as members of the land-owning elite sought to respond to the new market opportunities by taking a more rational approach to agricultural production. In areas of central Italy, peasant farms were increasingly put under pressure; not destroyed, as is clear from the archaeological record, but pushed towards the margins and disconnected from the networks of markets.47 Increasingly, families falling into difficulty through debt or illness preferred to move to the city, imagining the golden opportunities that might be found there; to keep this ever-growing urban population quiet and avoid giving further opportunities to populist politicians, the state needed to use its revenue to subsidise the city food supply and provide public services – which attracted further migrants. Faced with an apparent crisis in the peasantry, the traditional source of soldiers, the state began to recruit from the capite censi, those counted by head in the census because they failed to meet the lowest wealth qualification. The result was an increasingly professionalised army, but one loyal to its commanders rather than to the state because it was the general who depended on his troops for power and security, who took responsibility for compelling the senate to allocate land for veteran settlement and thus provided security for retired soldiers. Such armies were powerful tools in the hands of individual generals, but at the same time they placed their commanders in the position of having to fight further wars in order to maintain their position.

Rome continued to make war because it had no choice; the alternative seemed to be the collapse of the political system and the revolutionary redistribution of the rewards of empire in a way that was unacceptable to those who held power, even though the stability of society was being undermined by the very processes that had sustained and driven Roman imperialism. The result, after a series of civil wars between the remaining dynasts, was twofold: the replacement of the republican system with a monarchy, albeit one which retained many of the old forms and titles and professed itself to be a restoration of the republic, and the end of the cycle of conquests.48 The trend towards exploitation rather than violent appropriation had been developing for some time, but the advent of the Principate accelerated the process. Social stability now required the steady stream of revenue that could be gained from exploiting existing provinces rather than seizing new ones; Italy was no longer a reliable source of military recruits, whereas the provinces were beginning to reveal their potential as a source of manpower. Emperors were no longer competing directly with anyone (except their predecessors and the idealised image of the good emperor) and were more concerned to limit the possibility of anyone else gaining glory than to win it themselves. The emperor effectively became the state (not least through a stupendous effort of image creation and propaganda under Augustus), so that the loyalty of the army was, generally, focused on his person and thus subordinated to the interests of the Empire. Above all, the emperor’s claim to legitimacy was that he brought peace to the Empire, and breaking what had become a destructive relationship between wealth, power and war was a prerequisite for that. Of course, the Roman conception of ‘peace’ did not necessarily accord with that of their subjects.

Endnotes

- History of the Punic wars: clear summary by Gargola, D.A., ‘Mediterranean empire (264–134)’, in Rosenstein, N. & Morstein-Marx, R. (eds), A Companion to the Roman Republic (Malden & Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), pp. 147–66; more detailed accounts in Goldsworthy, A., The Punic Wars (London: Cassell, 2000); Hoyos, B.D., Unplanned Wars: the origins of the First and Second Punic Wars (Berlin & New York: de Gruyter, 1998); Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal’s War (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1978). On the history of Carthage, Lancel, S., Carthage: a history, trans. Neill, A. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995).

- Ridley, R.T., ‘To be taken with a pinch of salt: the destruction of Carthage’, Classical Philology, 1986 (81), pp. 140–6.

- For general discussions of ‘Roman imperialism’, see Garnsey, P.D.A. & Whittaker, C.R., ‘Introduction’, in Garnsey & Whittaker (eds), Imperialism in the Ancient World (Cambridge: Cambridge Philological Society, 1976), pp. 1–6; Champion, C.B. & Eckstein, A.M., ‘Introduction: the study of Roman imperialism’, in Champion (ed.), Roman Imperialism: readings and sources (Malden & Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), pp. 1–10; Eckstein, A.M., ‘Conceptualising Roman imperial expansion under the republic: an introduction’, in Rosenstein & Morstein-Marx, Companion to the Roman Republic, pp. 567–89.

- Brunt, P.A., ‘Laus imperii’, in Garnsey & Whittaker, Imperialism in the Ancient World, pp. 159–91.

- For a summary and critique of defensive imperialism, Harris, W.V., War and Imperialism in Republican Rome 327–70 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 163–54.

- de Sepulveda, Gines, (1550) and de Vitoria, Francisco, (1539), cited and discussed by Lupher, D.A., Romans in a New World: classical models in sixteenth-century Spanish America (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

- Baring, E., Earl of Cromer, Ancient and Modern Imperialism [1910] (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2001), pp. 19–20.

- For example, the term does not appear in the index of Flower, H. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- Morley, N., Theories, Models and Concepts in Ancient History (New York & London: Routledge, 2004).

- Frank, T., Roman Imperialism (New York: Macmillan, 1914), pp. 120–1.

- See generally Betts, R.F., ‘The allusion to Rome in British imperialist thought of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’, Victorian Studies, 1971 (15), pp. 149–59.

- Lucas, C.P., Greater Rome and Greater Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1912), p. 59.

- Bukharin, N., Imperialism and World Economy [1915] (London: Bookmarks, 2003), pp. 118–19.

- Ibid., p. 119. Generally on Marxist approaches, Brewer, A., Marxist Theories of Imperialism: a critical survey (2nd edn) (London & New York: Routledge, 1990).

- See generally Kemp, T., Theories of Imperialism (London: Dennis Dobson, 1967).

- cf. Scheidel, W., ‘Sex and empire: a Darwinian perspective’, in Morris, I. & Scheidel, W. (eds), The Dynamics of Ancient Empires (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 255–324.

- Lenin, V.I., Imperialism, the Highest State of Capitalism (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1970), p. 97.

- See generally Rosenstein & Morstein-Marx, Companion to the Roman Republic.

- Whitmarsh, T., Greek Literature and the Roman Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), and further discussion in Ch. 4 below.

- See above, all the discussions in North, J.A., ‘The development of Roman imperialism’, Journal of Roman Studies, 1981 (71), pp. 1–9, and Rich, J., ‘Fear, greed and glory: the causes of Roman war-making in the middle Republic’, in Rich, J. & Shipley, G. (eds), War and Society in the Roman World (New York & London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 38–68; more generally, Reynolds, C., Modes of Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), pp. 124–71.

- Wiseman, T.P., Roman Drama and Roman History (Exeter: Exeter University Press, 1998).

- Raaflaub, K., ‘Born to be wolves? Origins of Roman imperialism’, in Wallace, R.W. & Harris, E.M. (eds), Transitions to Empire: essays in Greco-Roman history 360–146 BC (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), pp. 271–314.

- Harris, War and Imperialism,pp. 54–130.

- Richardson, J., Hispaniae: Spain and the development of Roman imperialism, 218–82 BC (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

- North, ‘Development of Roman imperialism’.

- Polybius, 32.13.7–9.

- Eckstein, ‘Conceptualising’, pp. 570–1.

- See further Ch. 3 below.

- On the publicani, Badian, E., Publicans and Sinners: private enterprise in the service of the Roman Republic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972).

- Harris, War and Imperialism, pp. 9–53.

- Beard, M., The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

- e.g. Loomba, A., Colonialism/Postcolonialism (London & New York: Routledge, 1998), pp. 5–10;Bush, B., Imperialism and Postcolonialism (Harlow: Pearson, 2006), pp. 48–50.

- Robinson, R., ‘Non-European foundations of European imperialism: sketch for a theory of collaboration’, in Owen, R. & Sutcliffe, R. (eds), Studies in the Theory of Imperialism (London: Longman, 1972), pp. 117–40; discussed by Mommsen, W.J., Theories of Imperialism, trans. Falla, P.S. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1981), pp. 70–112.

- cf. Mommsen, W.J., ‘The end of empire and the continuity of imperialism’, in Mommsen, W.J. & Osterhammel, J. (eds), Imperialism and After: continuities and discontinuities (London: Allen & Unwin, 1986), pp. 333–58.

- Doyle, Empires, pp. 88–92; Eckstein, ‘Conceptualising’.

- How, W.W. & Leigh, H.D., A History of Rome to the Death of Caesar (London, New York & Bombay: Longmans, Green & Co., 1896), p. 235.

- e.g. Bender, P., ‘The New Rome’, in Bacevich, A.J. (ed.), The Imperial Tense: prospects and problems of American empire (Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, 2003), pp. 81–92; Ferguson, N., Colossus: the price of America’s empire (London: Penguin, 2004); Lal, D., In Praise of Empire: globalization and order (New York & Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). For a critique of such arguments, see Mooers, C., ‘Nostalgia for empire: revising imperial history for American power’, in Mooers, C. (ed.), The New Imperialists: ideologies of empire (Oxford: Oneworld, 2006), pp. 111–35.

- Epitomised by Waltz, K., Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA & London: Addison-Wesley, 1979); a brief but clear summary, and discussion of its application to Rome, in Eckstein, ‘Conceptualizing’, pp. 577–80.

- cf. Doyle, Empires, pp. 125–7.

- Excellent summary in Beard, M. & Crawford, M., Rome in the Late Republic: problems and interpretations (London: Duckworth, 2nd edn, 1999), pp.12–24.

- Ibid., pp. 53–5.

- This section is heavily indebted to the ideas of Rosenstein, N., Rome at War: farms, families and death in the Middle Republic (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

- Hopkins, K., ‘The political economy of the Roman empire’, in Morris & Scheidel (eds), Dynamics of Ancient Empires, pp. 178–204.

- Rich, J., ‘The supposed manpower shortage of the lated second century BC’, Historia, 1983 (32), pp. 287–331.

- Hopkins, K., Conquerors and Slaves: sociological studies in Roman history I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 1–78; de Ligt, L. & Northwood, S. (eds), People, Land and Politics: demographic developments and the transformation of Roman Italy, 300 BC – AD 14 (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

- Rosenstein, Rome at War.

- Morley, N., Metropolis and Hinterland: the city of Rome and the Italian economy, 200 BC – AD 200 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- Cornell, T.J., ‘The end of Roman imperial expansion’, in Rich & Shipley (eds), War and Society, pp. 139–70.

Chapter 1 (14-37) from The Roman Empire: Roots of Imperialism, by Neville Morley (Pluto Press, 08.04.2010), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.