Early Americans formed a patchwork system that kept many from destitution.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Moral Economy of Assistance

In the formative centuries of American life—from the colonial period through the early republic—the care of the poor was not an abstract policy question but an immediate and visible social reality. In the absence of a national welfare system, responsibility for economic aid to the needy fell to a complex tapestry of local institutions, community norms, religious convictions, and voluntary charities. What emerged was a decentralized and morally charged relief structure that reflected both the ideals and contradictions of early American society. Central to this system were local governments and churches, which collaborated and occasionally competed in the provision of food, clothing, fuel, employment, and, in some cases, housing. While uneven and frequently punitive in character, community and charitable relief in early America laid the foundations for later welfare systems and revealed a society deeply concerned with the preservation of social order through the management of poverty.

Colonial Precedents and the English Poor Law Legacy

The earliest American approaches to poor relief were profoundly shaped by English models, particularly the Elizabethan Poor Laws of 1601. These laws distinguished between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor and mandated that local parishes—or townships, in the American context—bear the responsibility for their care. The colonists brought with them this dual commitment to localism and moral distinction, creating systems where aid was administered at the town level and governed by a mix of religious duty, social control, and civic necessity.¹

In New England especially, the Puritan ethic fused moral stewardship with practical governance. Town selectmen and overseers of the poor were tasked with assessing applications for aid and allocating scarce resources. Relief could take the form of food, fuel, clothing, or—when absolutely necessary—cash. But even as townships provided this support, they were also empowered to “warn out” newcomers who might become public charges, reinforcing the local and exclusionary nature of the early American welfare ethos.²

Forms of Assistance: Outdoor and Indoor Relief

Community relief in early America took two primary forms: outdoor relief, which allowed recipients to remain in their homes, and indoor relief, which involved institutional care in almshouses or poor farms. Outdoor relief was the more common form in the colonial and early national periods. It included small grants of money, in-kind provisions (such as firewood or flour), and payments to neighbors or relatives willing to care for destitute individuals. This model preserved the dignity and independence of recipients to a degree and allowed the community to maintain close supervision over those it supported.³

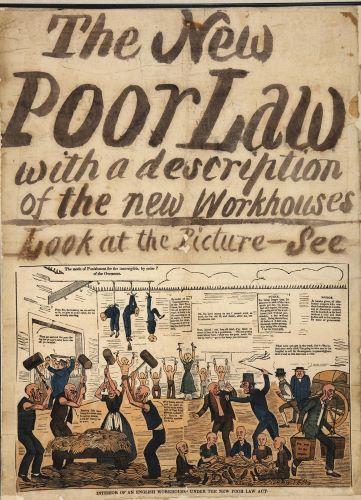

Indoor relief, by contrast, emerged as a solution for those who were elderly, infirm, mentally ill, or otherwise unable to care for themselves. Almshouses, which first appeared in the seventeenth century and became more widespread by the eighteenth, offered minimal shelter and subsistence in exchange for institutional control. Poor farms followed in the nineteenth century, designed to turn poverty into labor and self-discipline. Both forms of indoor relief reflected a shift in the perception of poverty—from a shared misfortune to a condition needing regulation and reform.⁴

Religious and Voluntary Charities

While town governments played a leading role in early relief, religious institutions were equally vital. Churches often maintained poor funds derived from tithes or special offerings. These resources were used to assist members of the congregation, and in many cases, churches also operated their own schools, orphanages, or hospitals.

In urban centers, religious benevolence expanded beyond denominational boundaries through the formation of voluntary societies. By the early nineteenth century, groups such as the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children (founded in New York in 1797) and the Boston Female Asylum (founded in 1800) emerged to fill gaps in the fragmented public system.⁵ These organizations were often run by middle- and upper-class women who saw charitable work as a moral calling and a socially acceptable public role. Their efforts provided food, clothing, temporary lodging, and, occasionally, financial aid to help families remain housed and fed.

Such voluntary societies frequently operated within a framework of moral reform, offering aid contingent upon recipients’ sobriety, work ethic, or church attendance. This conditionality, while limiting, reflected a widespread belief that poverty was not only economic but spiritual and behavioral. Still, for many recipients, these organizations represented a lifeline that might prevent starvation or homelessness.

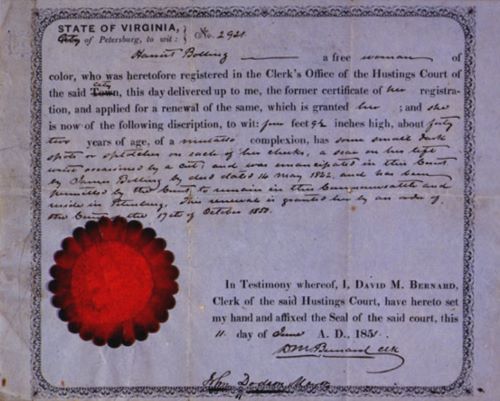

Mutual Aid and Self-Help among Marginalized Communities

In addition to official and religious channels, many marginalized groups developed their own systems of mutual aid. Free Black communities in the North established benevolent societies in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to provide burial insurance, financial assistance, and emergency support for rent or housing.⁶ Immigrant communities, too—especially the Irish and German—formed ethnic mutual aid organizations that provided rudimentary health insurance, job placement, and temporary housing.

These forms of community self-help were born of necessity. Excluded from public aid or subject to discrimination by white-dominated charities, these groups built parallel structures of support rooted in solidarity and shared experience. Though often short on funds, mutual aid societies demonstrated resilience and communal commitment to survival in the face of exclusion.

Community Relief and Housing Support

Though not framed as “rental assistance” in modern terms, early American communities did offer limited forms of housing support as part of their broader relief efforts. Overseers of the poor were sometimes authorized to pay the rent of destitute families, especially widows, the elderly, or single mothers, for short periods. In other cases, towns arranged for the poor to be “boarded out” with local families, paying those households a small fee to shelter someone who would otherwise be homeless.⁷ This system functioned as a highly informal housing subsidy and was most common in New England towns, where community oversight was strongest.

Almshouses and poorhouses provided shelter for the most desperate cases, though at the cost of freedom, privacy, and often family unity. These institutions typically required able-bodied residents to work and sometimes separated children from parents. As cities grew and housing costs rose in the early nineteenth century, urban areas began facing greater pressure to address housing instability. Yet responses remained local, uneven, and often punitive.

In time, debates over the cost and morality of aiding the poor shifted many municipalities away from outdoor relief toward institutional solutions. By the mid-nineteenth century, many cities had cut off rent subsidies entirely, believing them to encourage dependency. This retreat marked the limits of early housing assistance and the increasing professionalization—and moralization—of poverty policy.⁸

Conclusion: The Roots of American Welfare Thinking

Community and charitable relief in early America was a localized and improvisational effort to confront poverty in a society that prized independence but feared disorder. While often guided by moral judgments and hampered by limited resources, early American towns, churches, and voluntary organizations nevertheless formed a patchwork system that kept many from destitution. Housing aid, though minimal, was embedded within these broader systems, reflecting an understanding that shelter was a foundational need—even if not recognized as a civic right.

The legacy of this period is complex. On the one hand, early American relief programs demonstrated a strong sense of community responsibility and innovation. On the other, they established patterns of conditionality, exclusion, and moral surveillance that would shape welfare policy well into the twentieth century. Understanding this history allows us to see how early Americans negotiated the tension between liberty and obligation, personal failure and structural want—tensions that continue to shape American welfare debates today.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 13–16.

- Ibid., 18–21.

- Walter I. Trattner, From Poor Law to Welfare State: A History of Social Welfare in America, 6th ed. (New York: Free Press, 1999), 45–47.

- Ibid., 60–63.

- Anne M. Boylan, The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 23–29.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 124–125.

- Trattner, From Poor Law to Welfare State, 67.

- Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 56–60.

Bibliography

- Boylan, Anne M. The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Katz, Michael B. In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America. New York: Basic Books, 1996.

- Trattner, Walter I. From Poor Law to Welfare State: A History of Social Welfare in America. 6th ed. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.