It was a deliberate hoax.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human. Although there were doubts about its authenticity virtually from the beginning (in 1912), the remains were still broadly accepted for many years, and the falsity of the hoax was only definitively demonstrated in 1953. An extensive scientific review in 2016 established that amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson was responsible for the fraudulent evidence.[1]

In 1912, Charles Dawson claimed that he had discovered the “missing link” between early apes and man. In February 1912, Dawson contacted Arthur Smith Woodward, Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum, stating he had found a section of a human-like skull in Pleistocene gravel beds near Piltdown, East Sussex.[2] That summer, Dawson and Woodward purportedly discovered more bones and artifacts at the site, which they connected to the same individual. These finds included a jawbone, more skull fragments, a set of teeth, and primitive tools.

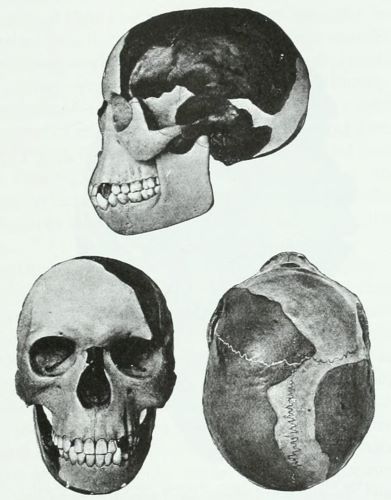

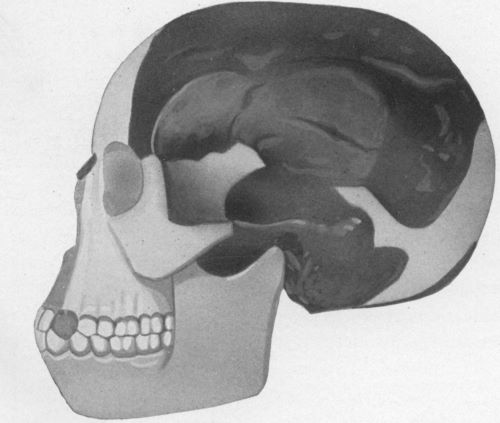

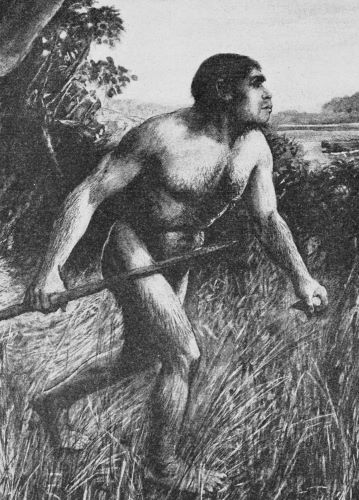

Woodward reconstructed the skull fragments and hypothesised that they belonged to a human ancestor from 500,000 years ago. The discovery was announced at a Geological Society meeting and was given the Latin name Eoanthropus dawsoni (“Dawson’s dawn-man”). The questionable significance of the assemblage remained the subject of considerable controversy until it was conclusively exposed in 1953 as a forgery. It was found to have consisted of the altered mandible and some teeth of an orangutan deliberately combined with the cranium of a fully developed, though small-brained, modern human.

The Piltdown hoax is prominent for two reasons: the attention it generated around the subject of human evolution, and the length of time, 41 years, that elapsed from its alleged initial discovery to its definitive exposure as a composite forgery.

The ‘Find’

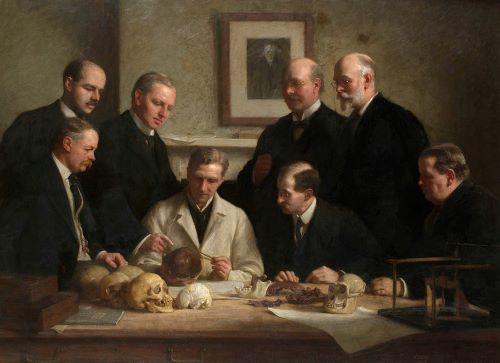

At a meeting of the Geological Society of London on 18 December 1912, Charles Dawson claimed that a workman at the Piltdown gravel pit had given him a fragment of the skull four years earlier. According to Dawson, workmen at the site discovered the skull shortly before his visit and broke it up in the belief that it was a fossilised coconut. Revisiting the site on several occasions, Dawson found further fragments of the skull and took them to Arthur Smith Woodward, keeper of the geological department at the British Museum. Greatly interested by the finds, Woodward accompanied Dawson to the site. Though the two worked together between June and September 1912, Dawson alone recovered more skull fragments and half of the lower jaw.[3][4] The skull unearthed in 1908 was the only find discovered in situ, with most of the other pieces found in the gravel pit’s spoil heaps. French Jesuit paleontologist and geologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin participated in the uncovering of the Piltdown skull with Woodward.[citation needed]

At the same meeting, Woodward announced that a reconstruction of the fragments indicated that the skull was in many ways similar to that of a modern human, except for the occiput (the part of the skull that sits on the spinal column), and brain size, which was about two-thirds that of a modern human. He went on to indicate that, save for two human-like molar teeth, the jaw bone was indistinguishable from that of a modern, young chimpanzee. From the British Museum’s reconstruction of the skull, Woodward proposed that Piltdown Man represented an evolutionary missing link between apes and humans, since the combination of a human-like cranium with an ape-like jaw tended to support the notion then prevailing in England that human evolution began with the brain.

The find was considered legitimate by Otto Schoetensack who had discovered the Heidelberg fossils just a few years earlier; he described it as being the best evidence for an ape-like ancestor of modern humans.[5]

But almost from the outset, Woodward’s reconstruction of the Piltdown fragments was strongly challenged by some researchers. At the Royal College of Surgeons, copies of the same fragments used by the British Museum in their reconstruction were used to produce an entirely different model, one that in brain size and other features resembled a modern human. This reconstruction, by Arthur Keith, was called Homo piltdownensis in reflection of its more human appearance.[6]

Woodward’s reconstruction included ape-like canine teeth, which was itself controversial. In August 1913, Woodward, Dawson and Teilhard de Chardin began a systematic search of the spoil heaps specifically to find the missing canines. Teilhard de Chardin soon found a canine that, according to Woodward, fitted the jaw perfectly. A few days later, Teilhard de Chardin moved to France and took no further part in the discoveries. Noting that the tooth “corresponds exactly with that of an ape”,[7] Woodward expected the find to end any dispute over his reconstruction of the skull. However, Keith attacked the find. Keith pointed out that human molars are the result of side to side movement when chewing. The canine in the Piltdown jaw was impossible as it prevented side to side movement. To explain the wear on the molar teeth, the canine could not have been any higher than the molars. Grafton Elliot Smith, a fellow anthropologist, sided with Woodward, and at the next Royal Society meeting claimed that Keith’s opposition was motivated entirely by ambition. Keith later recalled, “Such was the end of our long friendship.”[8]

As early as 1913, David Waterston of King’s College London published in Nature his conclusion that the sample consisted of an ape mandible and human skull.[9] Likewise, French paleontologist Marcellin Boule concluded the same in 1915. A third opinion from the American zoologist Gerrit Smith Miller Jr. concluded that Piltdown’s jaw came from a fossil ape. In 1923, Franz Weidenreich examined the remains and correctly reported that they consisted of a modern human cranium and an orangutan jaw with filed-down teeth.[10]

In 1915, Dawson claimed to have found three fragments of a second skull (Piltdown II) at a new site about two miles (3.2 km) away from the original finds.[3] Woodward attempted several times to elicit the location from Dawson, but was unsuccessful. So far as is known, the site was never identified and the finds appear largely undocumented. Woodward did not present the new finds to the Society until five months after Dawson’s death in August 1916 and deliberately implied that he knew where they had been found. In 1921, Henry Fairfield Osborn, President of the American Museum of Natural History, examined the Piltdown and Sheffield Park finds and declared that the jaw and skull belonged together “without question” and that the Sheffield Park fragments “were exactly those which we should have selected to confirm the comparison with the original type.”[8]

The Sheffield Park finds were taken as proof of the authenticity of the Piltdown Man; it may have been chance that brought an ape’s jaw and a human skull together, but the odds of it happening twice were slim. Even Keith conceded to this new evidence, though he still harboured personal doubts.[11]

Memorial

On 23 July 1938, at Barkham Manor, Piltdown, Sir Arthur Keith unveiled a memorial to mark the site where Piltdown Man was discovered by Charles Dawson. Sir Arthur finished his speech saying:

So long as man is interested in his long past history, in the vicissitudes which our early forerunners passed through, and the varying fare which overtook them, the name of Charles Dawson is certain of remembrance. We do well to link his name to this picturesque corner of Sussex—the scene of his discovery. I have now the honour of unveiling this monolith dedicated to his memory.[12]

The inscription on the memorial stone reads:

Here in the old river gravel Mr Charles Dawson, FSA found the fossil skull of Piltdown Man, 1912–1913, The discovery was described by Mr Charles Dawson and Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 1913–15.

Exposure

Scientific Investigation

From the outset, some scientists expressed scepticism about the Piltdown find (see above). Gerrit Smith Miller Jr., for example, observed in 1915 that “deliberate malice could hardly have been more successful than the hazards of deposition in so breaking the fossils as to give free scope to individual judgment in fitting the parts together”.[13] In the decades prior to its exposure as a forgery in 1953, scientists increasingly regarded Piltdown as an enigmatic aberration, inconsistent with the path of hominid evolution as demonstrated by fossils found elsewhere.[3]

In November 1953, Time magazine published evidence, gathered variously by Kenneth Page Oakley, Sir Wilfrid Edward Le Gros Clark and Joseph Weiner, proving that Piltdown Man was a forgery[14] and demonstrating that the fossil was a composite of three distinct species. It consisted of a human skull of medieval age, the 500-year-old lower jaw of an orangutan and chimpanzee fossil teeth. Someone had created the appearance of age by staining the bones with an iron solution and chromic acid. Microscopic examination revealed file-marks on the teeth, and it was deduced from this that someone had modified the teeth to a shape more suited to a human diet.

The Piltdown Man hoax succeeded so well because, at the time of its discovery, the scientific establishment believed that the large modern brain preceded the modern omnivorous diet, and the forgery provided exactly that evidence. Stephen Jay Gould argued that nationalism and cultural prejudice played a role in the ready acceptance of Piltdown Man as genuine, because it satisfied European expectations that the earliest humans would be found in Eurasia, and the British in particular wanted a “first Briton” to set against fossil hominids found elsewhere in Europe.[9]

Identify of the Forger

The identity of the Piltdown forger remains unknown, but suspects have included Dawson, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Arthur Keith, Martin A. C. Hinton, Horace de Vere Cole and Arthur Conan Doyle.[15][16]

The focus on Charles Dawson as the main forger is supported by the accumulation of evidence regarding other archaeological hoaxes he perpetrated in the decade or two before the Piltdown discovery. The archaeologist Miles Russell of Bournemouth University analysed Dawson’s antiquarian collection, and determined that at least 38 of his specimens were fakes.[17][18] Among these were the teeth of a multituberculate mammal, Plagiaulax dawsoni, “found” in 1891 (and whose teeth had been filed down in the same way that the teeth of Piltdown Man were to be some 20 years later); the so-called “shadow figures” on the walls of Hastings Castle; a unique hafted stone axe; the Bexhill boat (a hybrid seafaring vessel); the Pevensey bricks (allegedly the latest datable “finds” from Roman Britain); the contents of the Lavant Caves (a fraudulent “flint mine”); the Beauport Park “Roman” statuette (a hybrid iron object); the Bulverhythe Hammer (shaped with an iron knife in the same way as the Piltdown elephant bone implement would later be); a fraudulent “Chinese” bronze vase; the Brighton “Toad in the Hole” (a toad entombed within a flint nodule); the English Channel sea serpent; the Uckfield Horseshoe (another hybrid iron object) and the Lewes Prick Spur. Of his antiquarian publications, most demonstrate evidence of plagiarism or at least naive referencing. Russell wrote: “Piltdown was not a ‘one-off’ hoax, more the culmination of a life’s work.”[19] In addition, Harry Morris, an acquaintance of Dawson, had come into possession of one of the flints obtained by Dawson at the Piltdown gravel pit. He suspected that it had been artificially aged – “stained by C. Dawson with intent to defraud”. He remained deeply suspicious of Dawson for many years to come, though he never sought to discredit him publicly, possibly because it would have been an argument against the eolith theory, which Morris strongly supported.[20]

Adrian Lister of the UK’s Natural History Museum has said that “some people have suggested” that there may also have been a second ‘fraudster’ seeking to use outrageous fraud in the hope of anonymously exposing the original frauds. This was a theory first proposed by Miles Russell.[21] He has explained that the piece nicknamed the ‘cricket bat’ (a fossilised elephant bone) was such a crudely forged ‘early tool’ that it may have been planted to cast doubt upon the other finds, the ‘Earliest Englishman’ in effect being recovered with the earliest evidence for the game of cricket. This seems to have been part of a wider attempt, by disaffected members of the Sussex archaeological community, to expose Dawson’s activities, other examples being the obviously fraudulent ‘Maresfield Map’, the ‘Ashburnham Dial’, and the ‘Piltdown Palaeolith’.[22][23] Nevertheless, the ‘cricket bat’ was accepted at the time, even though it aroused the suspicions of some and ultimately helped lead to the eventual recognition of the fraud decades later.[24]

In 2016, the results[25] of an eight-year review[1] of the forgery were released, identifying Dawson’s modus operandi. Multiple specimens demonstrated the same consistent preparation: application of the stain, packing of crevices with local gravel, and fixation of teeth and gravel with dentist’s putty. Analysis of shape and trace DNA showed that teeth from both sites belonged to the same orangutan.[1] The consistent method and common source indicated the work of one person on all the specimens, and Dawson was the only one associated with Piltdown II. The authors did not rule out the possibility that someone else provided the false fossils to Dawson, but ruled out several other suspects, including Teilhard de Chardin and Doyle, based on the skill and knowledge demonstrated by the forgeries, which closely reflected ideas fashionable in biology at the time.

On the other hand, Stephen Jay Gould judged that Pierre Teilhard de Chardin conspired with Dawson in the Piltdown forgery.[26] Teilhard de Chardin had travelled to regions of Africa where one of the anomalous finds originated, and resided in the Wealden area from the date of the earliest finds (although others suggest that he was “without doubt innocent in this matter”).[27] Hinton left a trunk in storage at the Natural History Museum in London that in 1970 was found to contain animal bones and teeth carved and stained in a manner similar to the carving and staining on the Piltdown finds. Phillip Tobias implicated Arthur Keith in helping Dawson by detailing the history of the investigation of the hoax, dismissing other theories, and listing inconsistencies in Keith’s statements and actions.[28] Other investigations suggest that the hoax involved accomplices rather than a single forger.[29]

Richard Milner, an American historian of science, argued that Arthur Conan Doyle may have been the perpetrator of the Piltdown Man hoax. Milner noted that Doyle had a plausible motive—namely, revenge on the scientific establishment for debunking one of his favourite psychics—and said that The Lost World appeared to contain several clues referring cryptically to his having been involved in the hoax.[30][31] Samuel Rosenberg’s 1974 book Naked is the Best Disguise purports to explain how, throughout his writings, Doyle had provided overt clues to otherwise hidden or suppressed aspects of his way of thinking that seemed to support the idea that Doyle would be involved in such a hoax.[32] However, more recent research suggests that Doyle was not involved. In 2016, researchers at the Natural History Museum and Liverpool John Moores University analyzed DNA evidence showing that responsibility for the hoax lay with Dawson, who had originally “found” the remains. Dawson had initially not been considered the likely perpetrator, because the hoax was seen as being too elaborate for him to have devised. However, the DNA evidence showed that a supposedly ancient tooth Dawson had “discovered” in 1915 (at a different site) came from the same jaw as that of the Piltdown Man, suggesting that he had planted them both. That tooth, too, was later proven to have been planted as part of a hoax.[33]

Chris Stringer, an anthropologist from the Natural History Museum, was quoted as saying: “Conan Doyle was known to play golf at the Piltdown site and had even given Dawson a lift in his car to the area, but he was a public man and very busy[,] and it is very unlikely that he would have had the time [to create the hoax]. So there are some coincidences, but I think they are just coincidences. When you look at the fossil evidence[,] you can only associate Dawson with all the finds, and Dawson was known to be personally ambitious. He wanted professional recognition. He wanted to be a member of the Royal Society and he was after an MBE [sic[34]]. He wanted people to stop seeing him as an amateur”.[35]

Legacy

Early Humans

In 1912, the majority of the scientific community believed the Piltdown Man was the “missing link” between apes and humans. However, over time the Piltdown Man lost its validity, as other discoveries such as the Taung Child and Peking Man were made. R. W. Ehrich and G. M. Henderson note, “To those who are not completely disillusioned by the work of their predecessors, the disqualification of the Piltdown skull changes little in the broad evolutionary pattern. The validity of the specimen has always been questioned”.[36] Eventually, during the 1940s and 1950s, more advanced dating technologies, such as the fluorine absorption test, proved scientifically that this skull was actually a fraud.

Influence

The Piltdown Man fraud significantly affected early research on human evolution.[37] Notably, it led scientists down a blind alley in the belief that the human brain expanded in size before the jaw adapted to new types of food. Discoveries of Australopithecine fossils such as the Taung child found by Raymond Dart during the 1920s in South Africa were ignored because of the support for Piltdown Man as “the missing link,” and the reconstruction of human evolution was confused for decades. The examination and debate over Piltdown Man caused a vast expenditure of time and effort on the fossil, with an estimated 250+ papers written on the topic.[38]

The book Scientology: A History of Man by L. Ron Hubbard features the Piltdown Man as a phase of biological history capable of leaving a person with subconscious memories of traumatic incidents that can only be resolved by use of Scientology technology. Recovered “memories” of this phase are prompted by one’s obsession with biting, hiding the teeth or mouth, and early familial issues. Nominally, this appears to be related to the large jaw of the Piltdown Man specimen. The book was first published in 1952, shortly before the fraud was confirmed, and has since been republished 5 times (most recently in 2007).[39]

Creationists often cite the hoax (along with Nebraska Man) as evidence of an alleged dishonesty of paleontologists who study human evolution, although scientists themselves had exposed the Piltdown hoax (and the Nebraska Man incident was not a deliberate fraud).[40][41]

In November 2003, the Natural History Museum in London held an exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the exposure of the fraud.[42]

Biases in the Interpretation of the Piltdown Man

The Piltdown case is an example of how race, nationalism, and gender influenced scientific and public opinion. Newspapers explained the seemingly primitive and contradictory features of the skull and jaw by attempting to demonstrate an analogy with non-white races, presumed at the time to be more primitive and less developed than white Europeans.[43] The influence of nationalism resulted in the differing interpretations of the find: whilst the majority of British scientists accepted the discovery as “the earliest Englishman”,[44] European and American scientists were considerably more sceptical, and several suggested at the time that the skull and jaw were from two different creatures and had been accidentally mixed up.[43] Although Woodward suggested that the specimen discovered might be female, most scientists and journalists referred to Piltdown as a male. The only notable exception was the coverage by the Daily Express newspaper, which referred to the discovery as a woman, but only to mock the suffragette movement, of which the Express was highly critical.[45]

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 06.11.2002, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.