The caste system was enforced not only by law, but by a widespread campaign of terror, known as lynching.

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. Kenneth Warren

Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor

The University of Chicago

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 03.14.2013, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

Between 1915 and 1970, six million African Americans left their homes in the South and moved to states in the North and West. This massive movement of black citizens from one part of the United States to another is known as the Great Migration. Social conditions in the South provided many migrants with a strong incentive to leave: following Reconstruction, state legislatures throughout the South had passed laws mandating the separation of the races in every area of social life (marriage, housing, education, transportation, healthcare, recreation, and so on). Through these laws (known as Jim Crow) and social custom, southern states had systematically developed a severe racial caste system. Journalist and historian Isabel Wilkerson vividly illustrates this pervasive system of white supremacy in her book The Warmth of Other Suns: African Americans “had to step off the sidewalk when a white person approached, were banished to jobs nobody else wanted no matter their skill or ambition, couldn’t vote, but could be hanged on suspicion of the pettiest infraction … In everyday interactions, a black person could not contradict a white person or speak unless spoken to first.” This caste system was enforced not only by law, but by a widespread campaign of terror, known as lynching. Between 1880 and 1950, mobs of white men tortured and murdered approximately 3,500 African Americans, often before crowds of spectators, to avenge suspected violations of the social and legal code.

Yet the migrants were not only fleeing the injustice of the South, they were also recruited to the North by industries seeking to bolster the labor force. Since the early nineteenth-century, these industries had relied on a steady supply of workers from European countries. But, with the advent of World War I, foreign immigration rates plummeted, while demand for manufacturing increased, and Northern industries sent scouts to the South to recruit workers.

Chicago became one of the most important destinations for members of the Great Migration. By the end of the nineteenth century, the city had a large population of European immigrants. In 1890 three-quarters of the city’s population was first- or second-generation immigrant, that is, they or their parents had been born in another country. African Americans made up less than 2 percent of the city. These demographics changed rapidly during the first half of the twentieth century. The black population in Chicago more than doubled during World War I to around 100,000. By 1970, as the Great Migration drew to a close, there were one million African Americans in Chicago, a third of the city’s population.

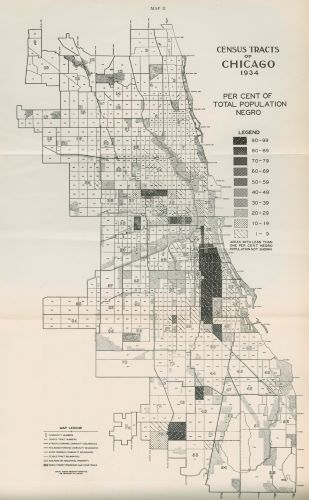

Most of these new arrivals to Chicago found themselves living in a narrow strip of blocks on the South Side, stretching from Twenty-second Street down to Fifty-first Street. The neighborhood was initially labeled the “Black Belt” or the “Black Ghetto,” but an African American writer suggested calling it “Bronzeville,” a name that many residents found less insulting.

Chicago did not build more housing to accommodate the new residents. Instead, as the years went on, more and more people crowded into dilapidated and overpriced tenements in Bronzeville, sometimes living without heat, light, or running water. The city did not have Jim Crow laws on the books, but segregation was enforced through a variety of social customs and residential codes. Among the most important of these were restrictive covenants, contractual agreements among property owners that prohibited the sale or lease of any part of a building to specific groups of people, usually African Americans. Historian Arnold R. Hirsch explains in The Encyclopedia of Chicago that the covenants were “rare in Chicago before the 1920s, their widespread use followed the Great Migration of southern blacks.” Restrictive covenants effectively confined African Americans to Bronzeville until courts began striking down the restrictions in the 1940s.

The Chicago Riots of 1919

Following the end of World War I, factories which had produced weapons and other war materiel began laying off workers and shutting down. The country faced recession. In Chicago, many black migrants who had responded to the wartime demand for cheap labor now found themselves without jobs. They also faced the resentment of many working-class whites, sometimes themselves migrants from the South, who shared this economic hardship and saw African American workers as competitors for scarce jobs. As historian Isabel Wilkerson writes, “Contrary to modern assumptions, for much of the history of the United States, … riots were often carried out by disaffected whites against groups perceived as threats to their survival. Thus riots would become to the North what lynchings were to the South, each a display of uncontained rage by put-upon people directed toward the scapegoats of their condition.”

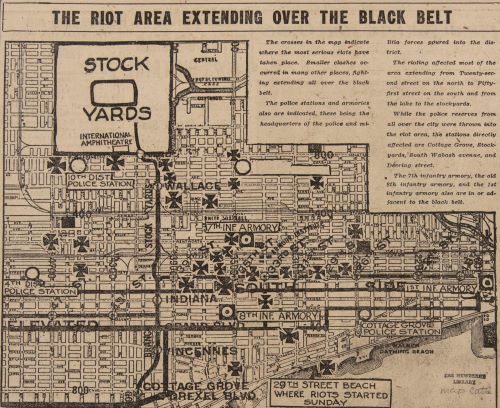

The Chicago Riot of 1919 started on July 27 with the drowning of a 17-year-old black boy when he swam across an unmarked line separating whites from blacks at the Twenty-ninth Street beach. A policeman refused to arrest the whites who had attacked the boy. Whites and blacks at the scene began throwing rocks at each other and the violence rapidly escalated throughout the area. As Wilkerson writes, “White gangs stormed the black belt, setting houses on fire, hunting down black residents, firing shotguns, and hurling bricks.” The riots lasted for more than a week until the state militia finally ended them. They left 38 people dead (23 blacks and 15 whites); 537 injured (342 blacks, 195 whites); and 1,000 people homeless. Critic Robert Bone argues that the 1919 riot became the defining event for members of the first wave of the Great Migration, the World War I generation.

Carl Sandburg, who would later become famous as a poet, wrote a series of articles on black migration and the riot for the Chicago Daily News. The second document is a map published by Chicago Tribune as part of its reporting on the riots as they were occurring. The final document shows a map of the black population in Chicago in 1934, 15 years after the riot, and vividly illustrates the persistence of residential segregation.

Travel during Jim Crow

African American travelers faced numerous challenges and humiliations in many parts of the United States from the late nineteenth century into the 1960s. As historian Isabel Wilkerson explains, between 1891 and 1905, “every southern state, from Florida to Texas, outlawed blacks from sitting next to whites on public conveyances.” Some cities went so far as to require entirely separate vehicles (white streetcars and black streetcars, white taxicabs and black taxicabs). Trains in the North were not segregated, but, if the trains were southbound, black passengers had to move to separate, Jim Crow cars at border cities, such as Washington DC.

As the twentieth century progressed, these laws and customs were extended from streetcars and trains to include buses and private cars. Wilkerson writes,

“Throughout the South, the conventional rules of the road did not apply when a colored motorist was behind the wheel. If he reached an intersection first, he had to let the white motorist go ahead of him. He could not pass a white motorist on the road no matter how slowly the white motorist was going and had to take extreme caution to avoid an accident because he would likely be blamed no matter who was at fault.”

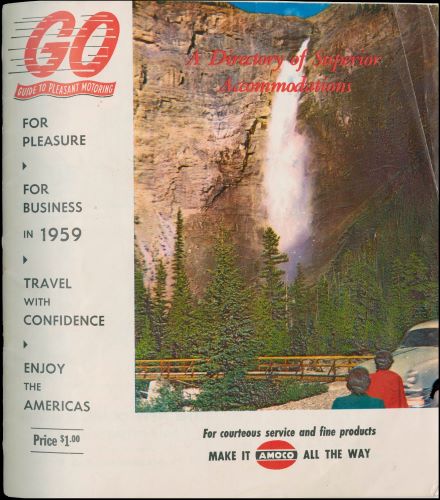

African Americans had to take special care to find places to spend the night while traveling. White-owned hotels in the South would not accept them, and even establishments in the North and West could be unpredictable. Wilkerson describes “a kind of underground railroad for colored travelers,” developing during the Great Migration. People spread information by word of mouth and guidebooks like the one below, produced in 1959 by Amoco American Oil Company. In 1956 the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the segregated bus laws in Montgomery, Alabama. But many southern states ignored the decision. It took years of sit-ins and demonstrations in the South and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 before segregation finally came to an end.

The Great Migration in Chicago Literature

Several decades ago, the literary critic Robert Bone suggested that the cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance (1920–1935) was followed by an equally important, if unrecognized, “second phase of Negro literary awakening”: the Chicago Renaissance. Bone identifies the novelist and memoirist Richard Wright as the central figure in a constellation of writers and artists who lived in or passed through Chicago between 1935 and 1950. Writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Bone argues, often responded to the experience of the Great Migration with nostalgia for the rural past; they celebrated the Southern black folk culture they had left behind. Chicago writers, in contrast, studied the urban experience of migrants, collaborated with sociologists and leftist radicals, and looked toward the future. The poems that follow provide a rich sense of the experiences of African American migrants. Gwendolyn Brooks grew up in Chicago in a family that had participated in the Great Migration, moving from Kansas to Chicago when she was an infant. She named this, her first collection of poetry, for the neighborhood of Bronzeville. The book brought her national acclaim.

The poet Langston Hughes was one of the most famous members of the Harlem Renaissance, the cultural movement of the 1920s and ’30s based in New York City. But Hughes spent time in Chicago as well and, in 1949, enjoyed three months as the poet-in-residence at the University of Chicago Laboratory School. The poems reproduced below were published that year. (Hughes maintained a relationship to Chicago’s literary scene, publishing a regular column in the African American newspaper, the Chicago Defender, from 1942 to 1962.)

Both poets write about kitchenettes, which in Bronzeville at this time meant cramped, one-room apartments, created when landlords divided up larger units and houses in order to accommodate more people. Kitchenettes might be occupied by entire families and often did not include their own bathrooms or kitchens. Hughes also refers to restrictive covenants, contracts between property owners that prohibited selling or leasing space to African Americans, and effectively confined blacks to the neighborhood of Bronzeville despite its shortage of decent housing.

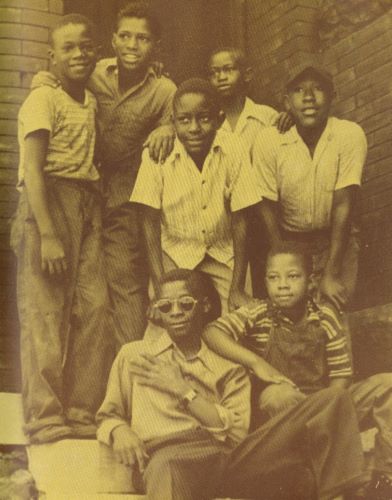

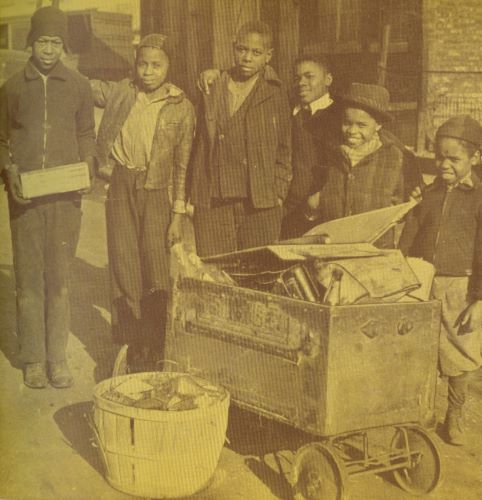

Bright Shadows in Bronzetown

The Southside Community Committee was an organization formed in 1942 to mobilize residents of Bronzeville (or Bronzetown) to address the problem of juvenile delinquency within the neighborhood. The organization’s leaders drew on the research of sociologists, such as Clifford Shaw, Horace Cayton, and St. Clair Drake, and decided to “transition from the traditional methods of philanthropy, which seeks to perform services for people to one in which the people become the chief participants in the study of problems, formulation of goals and purposes, determination of policies, and in the operation of activities programs.” The organization recruited “local citizens” from the neighborhood to design and lead programs for children.

Shaw, who wrote the preface to Bright Shadows in Bronzetown, devoted his career to studying the causes of delinquency among young men in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century. Shaw challenged the conventional wisdom that attributed delinquency—behavior that goes against social norms or breaks the law—to individual moral failings or specific racial and ethnic groups. He argued, instead, that delinquency was a normal human response to abnormal social conditions, conditions that he describes in the documents below.