A closer look at three iconic events that have been well documented in literature.

By Dr. Jitse H.F. Dijkstra

Professor of Classics and Religious Studies

University of Ottawa

Introduction: Towards a New Narrative of Religious Violence in Late Antique Egypt

Among the splendid Raphael rooms in the Vatican is the Hall of Constantine, which depicts four scenes from the life of Constantine illustrating the triumph of the Church. On the ceiling in the middle of this room is the famous painting Triumph of the Cross, completed in 1585 by Tommaso Laureti. We see a statue of a “pagan” god smashed to pieces on the ground and replaced with the cross (Figure 1).1

This captivating image of a violent clash between “pagans” and Christians from which the new religion rapidly emerged triumphant has long characterised studies of the religious transformation from the ancient religions to Christianity in late antiquity, the period from the fourth to seventh centuries C.E.2 Inspired by the work of Peter Brown, however, since the 1980s scholars have abandoned the monolithic view of a period dominated by a stark Christian-“pagan” conflict and a rapid transition to Christianity in favour of a more intricate web of religious interactions in a world that only gradually became Christian.3 Nevertheless, the idea that religious violence was endemic in the late antique world has remained influential. Our sources are full of book burnings, temple and statue destructions, and inter- and intra-religious violence. Perhaps unsurprisingly in a world where religious violence is so on our minds, the topic has received much attention in the last ten years and is currently one of the most hotly debated issues in Late Antique Studies.4

Despite a growing awareness of the complexity of the phenomenon, all of these studies have “violence” and/or “religion” (or similar words) in their titles without defining or even discussing the terms. This is surprising since both terms are highly complex and problematic, as demonstrated in a stream of recent publica-tions in Religious Studies analysing cases of religious violence in their modern contexts. If we concentrate on violence alone, for example, it can encompass a diversity of actions, from verbal abuse to actual physical violence. Moreover, these studies show that – despite the recent arguments proposed by Egyptologist and cultural historian, Jan Assmann, that religious violence is rooted in monotheism5 – the phenomenon exists in all places and times and even where violence is cast in religious terms, other factors (political, psychological, social, economic) are almost always involved. Consequently, religious violence needs to be analysed on a case-by-case basis and in the context of the particular local and historical circumstances in which it arises,6 a theoretical premise that has now also been applied to late antiquity.7

Such a nuanced understanding of religious violence fits in well with two recent trends within the field. First of all, scholars of Late Antique Studies are becoming increasingly critical of the (mostly Christian) literary accounts that describe violence between Christians and “pagans.”8 For example, one of the most detailed texts describing a temple destruction, the Life of Porphyry, by Mark the Deacon – while purporting to describe events in Gaza ca. 400 – has now been shown to date to the sixth century, which strongly diminishes its trustworthiness.9 The deconstruction of the literary evidence goes hand in hand with the increasing availability of large amounts of archaeological data. Until not too long ago, the picture of what happened to the temples in late antiquity was strongly influenced by a seminal study of Friedrich Deichmann who collected 89 cases of temple conversion and laid down a historical narrative in which violence against temples and their conversion into churches was a widespread phenomenon in the fourth and fifth centuries.10 The archaeological evidence that has now been collected for most parts of the Roman Empire, however, shows overwhelmingly that the destruction of temples and their reuse as churches were exceptional rather than routine events, and merely two aspects of the changing sacred landscape in late antiquity.11

I am currently working on a project that will build on these recent trends by conducting the first book-length study of religious violence in late antique Egypt.12 Thus far the idea that violence, in particular against temples and statues, was widespread in late antique Egypt has been persistent.13 To quote the much-discussed study Religion in Roman Egypt by David Frankfurter: “the gutting and conversion of traditional Egyptian temples, often still functioning, was a widespread phenomenon in Egypt during the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries.”14 My regional study of the process of religious transformation from the Ancient Egyptian religion to Christianity in the First Cataract region in southern Egypt, which exhaustively studies all sources from Philae and the two other towns in the region, Aswan and Elephantine, is a strong counter-argument against such views. It argues that the religious transformation in the whole region, including Philae, consisted of a gradual and complex process that was essentially peaceful.15 The present project extends the picture of a complex and gradual process of religious transformation, in which religious violence only occasionally occurred in specific local or regional circumstances, to Egypt as a whole.

Focusing on Egypt has the advantage that a wealth and variety of sources can be taken into account not found elsewhere in the Mediterranean. In addition to literary works, there is an abundance of inscriptions and extremely well-preserved archaeological material as well as papyri, a category of evidence preserved almost exclusively in Egypt. The project aims to bridge the gap between the ideological story of the literature and the evidence from other sources, in particular the archaeology. Part of the evidence is already presented in my study of the fate of the temples in late antique Egypt, in which I demonstrate, by confronting the literary works with the other sources available, that what happened to Egyptian temples conforms entirely to the complex picture that is now well established for the rest of the late antique world.16 By placing the incidents in a regional context of religious transformation as opposed to a context of violence, I hope to challenge the still pervasive view in current scholarship that religious violence was widespread in late antiquity. In the end, this project will not result in a dramatic picture of religious violence in late antique Egypt, such as now popularised in the Hollywood movie Agora (2009), but it will lead to an infinitely more accurate understanding of the complexity and diversity of this fascinating phenomenon.

Here I shall take a closer look at three iconic events that have been well documented in literature and at first sight might seem to confirm the impression that violence was widespread in late antique Egypt: the destruction of the Serapeum at Alexandria in 391/392, the anti-“pagan” crusade of Abbot Shenoute in the region of Panopolis ca. 400, and the closure of the Isis temple at Philae in 535–537. In fact, these events have often been quoted as perfectly illustrating the pervasive nature of religious violence in the late antique world. As I shall argue, when we take away the emphasis on violence and a stark Christian vs. “pagan” conflict that is so characteristic of the literary works and include the other sources available, and when we place the events in their regional contexts, a more nuanced picture arises, which shows that the representation of religious violence in the literary sources is based more on “wishful thinking” than reality.

The “Destruction” of the Serapeum at Alexandria

The first case that I wish to discuss, that of the Serapeum, in many ways constitutes an exception among the cases of religious violence to be discussed from elsewhere in Egypt. This is because Alexandria, with its huge, multi-ethnic population – one of the largest cities in the Roman Empire – had a long history of urban violence, a setting that is decidedly different from the Egyptian countryside, the chora, where violence was not present to the same extent. One only has to think of the tensions between the Jews and Greeks in the years 38–41, which the Emperor Claudius tried to ease in his famous letter to the Alexandrians.17 In his important study, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, Johannes Hahn has convincingly demonstrated that outbreaks of religious violence in late antique Alexandria should not be seen in exclusively religious terms, as many of our literary sources do, but rather as a socio-political phenomenon arising from deep-seated social tensions. For example, he sees the disturbances in the capital during the episcopate of George of Cappadocia (357–361), including an earlier plundering of the Serapeum and eventually the lynching of George himself, not so much as a Christian-“pagan” conflict but rather as a direct result of the rift caused by the imperial appointment of this controversial Arian bishop.18

The so-called destruction of the Serapeum, about thirty years later, is perhaps the best-documented case of religious violence in the late antique world. We have no fewer than four accounts by the church historians Rufinus, Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret, and even a non-Christian account, by the sophist Eunapius, which were all written within slightly over half a century of the incident.19 Yet these accounts offer a far from consistent reconstruction of the events and contradict each other on numerous points. As we shall shortly see, not even its exact date is known. Hahn has done an admirable job in teasing out the evidence and placing the incident within its socio-political context.20 In two respects, however, I think his analysis can still be improved on.

First of all, unlike previous scholarship, in particular the excellent study by Françoise Thelamon, who relied heavily on the earliest Christian account by Rufinus in 401/402,21 Hahn is highly critical of Rufinus and places great weight instead on Socrates (writing between 439 and 443).22 Whereas Hahn is right that we have to take into account the triumphal overtones in Rufinus, Socrates’ version is even more problematic in that it starts with an alleged edict by the Emperor Theodosius I giving carte blanche to Bishop Theophilus to destroy the temples in Alexandria.23 It is only after the destruction of the Serapeum that riots break out with the “pagans.” If one looks at imperial legislation regarding temples during the fourth century as preserved in book 16 of the Codex Theodosianus, however, it is clear that such an edict could never have been promulgated. Imperial policy before 435 was not aimed at the destruction of temples and the emperor would certainly not have given powers to act against temples to a local bishop.24 On 16 June 391, an edict was indeed promulgated at Alexandria, forbidding sacrifice and the access to temples and this law has often been directly connected to the Serapeum incident.25 However, this law does not, and could not, call for the destruction of temples and should merely be taken as a terminus post quem for the Serapeum incident, which makes Socrates’ version of the events highly suspect.26

The second point is that Hahn, while giving pride of place to Socrates, adds elements from the other accounts in order to provide a coherent picture of the events.27 However, a sounder historical method would be to discuss the accounts in chronological sequence, starting with the earliest preserved account, the one by Eunapius in 399, and paying detailed attention to the interrelations between the sources. While we have to leave such a close literary analysis to another occasion, it can be said in general that the order of events as described by Rufinus seems the most plausible: an incident involving the Christian reuse of a former temple leads to riots, which soon centre on the Serapeum complex, where the violence gets out of hand and is directed against the temple, leading to the end of its cults. The involvement of the highest imperial authorities in Egypt, the governor (praefectus augustalis) Evagrius and the highest military commander (comes Aegypti) Romanus, and an imperial rescript sent in response to the riots, seem in line with how the state would respond to such a situation and, although it cannot have taken the form Rufinus gives it – that the Christians who died are to be considered martyrs and should not be avenged, and that the “cause of the trouble” should be taken away (which is clearly interpreted here as an order to destroy the Serapeum) – a more neutral imperial order to make an end to the public disorder is likely.28

Concerning the other accounts, it is clear that Socrates’ account is a condensed version of Rufinus, reversing the events (Rufinus: riots – rescript – destruction; Socrates: edict – destruction – riots). No doubt he does this in an effort to provide a clearer cause for the destruction of the Serapeum, in which he could have interpreted the edict of 391 in hindsight as providing the trigger for the incident by making imperial involvement into an outright imperial order to destroy the temples. He does add an eyewitness account from two of his teachers in Constantinople, Helladius and Ammonius, who had fled after the incident, showing the impact that the event had on the Alexandrian philosophical schools. Sozomen relies mostly on Rufinus for the chronology but replaces the rescript with Socrates’ imperial call for the destruction of all Alexandrian temples. Finally, Theodoret’s version, which starts from an Empire-wide edict to destroy temples, focuses entirely on Theophilus and embellishes Rufinus’ scene of the striking of the statue of Serapis by adding that mice came out of it, is so concocted that it is hardly useful for reconstructing the events.

What we are left with after a close reading of the sources is disappointingly little: a general sense of how the events unfolded, in which the chain of events as described by Rufinus is the most likely, with the Alexandrian church under Bishop Theophilus and some Greek philosophers in opposing camps, and the imperial authorities trying to do something about the situation. Because of the literary colouring of the events, which are presented, even in Eunapius, in clear Christian-“pagan” terms, precise details are forever lost to us and we can only speculate about what is the most plausible scenario.

There are two sources that have the potential to shed further light on these literary accounts, however. The first of these is the archaeological evidence studied in recent years by the Oxford team under Judith McKenzie. On the basis of previous excavations and their own observations of what little is left of the foundations, it has been possible to reconstruct both the Ptolemaic- and Roman-phase temple and to refine its building history.29 The work of McKenzie and her team has also led to some clarifications regarding the fate of the Serapeum in the fourth century.30 No new structures were added to the temple precinct at this time, which argues against the account of Sozomen who states that under Arcadius (395–408) a church was built inside the temple.31 Moreover, architecturally it would have been difficult to turn the Serapis temple into a church. Remains of Christian buildings, including a church, have been found west of the temple terrain, which seems in line with Rufinus’ remark that churches were built on either side of the Serapeum, though where the other church was located remains unclear.32 The extent to which the Serapeum was destroyed will probably remain an unresolved question. In any case, in the Arab period the colonnade surrounding the temple was still intact and it seems most probable that the temple was not immediately destroyed but – having been deprived of its primary function – only gradually dismantled over time.33

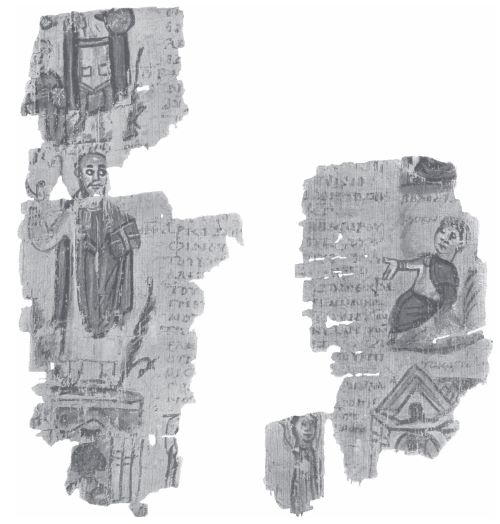

The second source to be considered is the “Alexandrian World Chronicle.” This fragmentary illustrated papyrus codex is best known for its leaf (fol. VI) containing a list of consuls of 383–392 C.E. with occasional historical entries. It includes, on its back side, an entry on the destruction of the Serapeum listed under the year 392, with in the left margin a famous depiction of the victorious Bishop Theophilus on top of the Serapeum, and another illustration of the temple in the lower right corner (Figure 2).

In his 2006 article, Hahn has argued at length that the entry proves that the incident took place in 392.34 His arguments are based on the assumption that this is the last leaf of the manuscript and that the work dates to shortly after 412, that is, fairly close to the events. As this was the last entry of the work, it formed a “grand finale,” highlighting the triumph of the Alexandrian church. Therefore the scribe could not possibly have made an error in the date, which must be 392, more specifically before April of that year when Evagrius, who as we have seen was involved in the event and is also mentioned as the governor of Egypt for this year in the papyrus, was out of office.35

A detailed study of the text undertaken with my colleague Richard Burgess, however, has revealed that this text cannot be used for dating the event, first and foremost because the papyrus dates to the second half of the sixth century, not shortly after 412, and is thus significantly removed in time from the event it is recording. Furthermore, the work would almost certainly not have ended with the 392 entry but rather continued until the time of compilation in the sixth century, as we know is the case with such chronicle texts. Finally, the other historical entries in the same text are full of mistakes, increasing the likelihood that this date, too, is incorrect. Thus, the date has been opened up again to between 16 June 391, the date of the edict of Theodosius I, and 8 April 392, the latest possible date of Evagrius being in office.36 The illustration does provide us with an interesting, sixth-century Christian perspective on the event, which already developed at an early stage, of Theophilus making a definitive end to the “pagan” cults in the city.

Shenoute of Atripe’s Anti-“Pagan” Crusade

Our second case is that of Shenoute (ca. 385–465), the main author of Coptic literature and abbot of the homonymous monastery situated on the west bank of the Nile at Panopolis (modern Akhmim), commonly referred to as the White Monastery. In his classic study of Shenoute, the German Coptologist Johannes Leipoldt made Shenoute into a religious fanatic, roaming the countryside on the lookout to destroy temples: “The Copts of his time had only one passion: this was the hatred against the ‘Greeks’, the pagans. And this hatred restlessly stirred up Shenoute and aroused in him the blazing flame to reduce one temple after the other to ashes.”37 His view has been extremely persistent, witness for example the words of David Bell, the translator of the Bohairic Life of Shenoute into English, who – paraphrasing an earlier characterization of Shenoute by Émile Amélineau – describes him as “an erupting volcano: an impressive sight, though not necessarily a pretty one.”38

Meanwhile, however, the lifelong work of Stephen Emmel on the dispersed and ruinous works of Shenoute has placed the study of his literary corpus on a new footing and an international effort led by Emmel is underway of making it systematically available to the scholarly world.39 While definitive conclusions must await further study of Shenoute’s works, Emmel has conducted a meticulous analysis of all available passages on religious violence in the Shenoutian corpus. His study shows that there is only one secure case of a temple destruction in Shenoute’s works, that of the temple of Atripe, in which idols were destroyed and the temple was set on fire. Shenoute was also, albeit rather indirectly, involved in the “destruction” of another temple, that of Pneueit, in which he defended in court at Antinoopolis some Christians who had been accused of the demolition. Shenoute is most well known, however, for his actions against the local aristocrat Gessios, whom he singles out as a “pagan.” According to his own version of the events, Shenoute stole into his house at night, robbed him of his house statues and threw them into the Nile.40

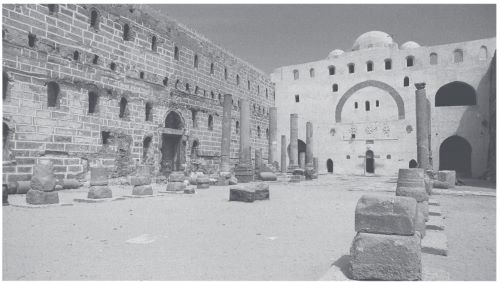

It has been assumed since Leipoldt, without any good grounds, that following its “destruction” Shenoute dismantled the temple of Atripe (Greek Athribis) and reused the blocks in his monastery, where reused materials are still visible today (Figure 3).41 A recent archaeological investigation of the temple of Athribis demonstrates, however, that Shenoute could not have completely dismantled the temple. This picture is confirmed by a study of the spolia reused in the Shenoute Monastery, which derive not from one but various different monuments that were probably no longer functioning by the mid-fifth century. Among the reused materials some slabs from the temple of Atripe have indeed been detected, but they only come from its roof and certainly do not provide evidence for extensive reuse of building material from this site. In fact, the temple was largely left intact and gradually incorporated into the adjacent nunnery, also part of the monastic net-work of Shenoute, from the early fifth century onwards, which suggests that – as we might expect at this time – this temple, too, was no longer in use for Ancient Egyptian cults and practices.42

As with the “destruction” of the Serapeum, we should therefore be cautious in assuming wholesale destruction of temple buildings and idols out of religious frenzy. While the incidents described in Shenoute’s works no doubt go back to actual events, the image of Shenoute as an anti-“pagan” crusader does not hold and is clearly more rhetoric than reality. In this case too, more was at stake than purely religious motivations. In fact, as a recent study by Ariel Lόpez shows, the anti-“pagan” measures of Shenoute can be placed in the context of his power struggle with the local elite at Panopolis on the other side of the Nile, as embodied especially in Gessios.43 That Shenoute’s actions were not always uncontroversial appears from the indignant reactions to the nightly raid on Gessios’ house, after which Shenoute had to write an open letter to the citizens of Panopolis to defend his deed.44

The Closure of the Temple of Isis at Philae

The last case that we shall consider is that of the Isis temple at Philae. The famous temple island has often been considered as an exceptional story.45 Due to its location on the southern Egyptian frontier, Philae retained its traditional attraction to the southern peoples from the other side of the frontier, the Blemmyes and Nou-bades, and managed to stay open for much longer than any other major Egyptian temple. It is here that we find the last inscriptions in the Ancient Egyptian scripts hieroglyphic and demotic, dating to 394 and 452, respectively. It is interesting to observe, however, that despite these special circumstances it has been presupposed that the end of the cults at Philae also occurred in a context of religious violence – a situation that is usually more associated with the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth century, the time of the Serapeum incident and Shenoute. According to this picture, the “last bastion of pagan worship” remained open until 535–537 when the Emperor Justinian himself had to intervene to close it. This picture is based on the account by the sixth-century Byzantine historian Procopius, who writes:

These barbarians retained the temples on Philae right down to my day, but the Emperor Justinian decided to destroy them. Accordingly, Narses, . . . destroyed the temples on the emperor’s orders, held the priests under guard, and sent the statues to Byzantium.46

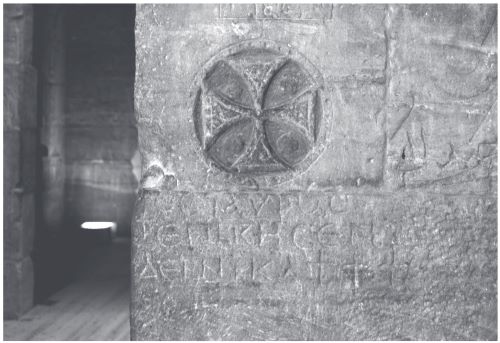

In an influential article published in 1967, the Patristics scholar Pierre Nautin connected this incident to the dedicatory inscriptions of a church of St. Stephen inside the temple, especially the one next to the door leading towards the main sanctuary or naos, which says: “The cross has conquered, it always conquers!” (Figure 4).47

In Nautin’s view the Christian community on the island, annoyed by the continuation of the “pagan” cults until such a late date, must have felt a sense of triumph when they finally entered the holiest part of the temple, the naos. Their feelings were embodied in the inscription of the conquering cross. According to Nautin, this inscription therefore has to be taken quite literally: in a pious ceremony the bishop of Philae, Theodore, would have brought a cross inside the naos and erected it there to replace the cult image of Isis: “from then on, the whole island was for the Christians.”48 The circle is complete: we are back at the evocative image of the Triumph of the Cross with which we started this article.

My study of the religious transformation in the region of Aswan, based on all available sources from the region, has disentangled many presuppositions that have contributed to this triumphalist image, which has made the reuse of the temple of Isis into perhaps the most famous case of a temple conversion in Egypt.49 First of all, Procopius’ account is not unproblematic. As everyone can still see today, the Isis temple is among the best-preserved temples in Egypt. It could not therefore have been “destroyed,” as Procopius says, although most scholars have recognised this and speak only of a “closure” of the temple.50 The historian also gives the impression that the southern peoples continued to worship Isis undisturbed until the sixth century, but this completely ignores the impact that Christianity must have had on the island. Philae probably had a see from as early as 330 onwards and a cathedral church, known as the East Church, was situated on the northern part of the island. This means that Christians and worshippers of Isis lived peacefully side by side for over a century. At the same time, the expansion of Christianity at Philae conforms entirely to similar developments in the rest of the region or, for that matter, in Egypt as a whole.

Moreover, my analysis of the no less than thirty-five inscriptions in demotic and Greek from the last priests of Isis indicate that the Ancient Egyptian cults already show signs of contraction and isolation from the early fourth century onwards. When the last inscription was incised, significantly written in Greek in 456/457, a continuous recording by these priests from time immemorial came to an end, so that it is highly likely that cultic practice stopped soon after, if not in the same year.51 As a result, the closure that Procopius describes, some eighty years later, cannot have been more than a symbolic closure – we know that Justin-ian closed other temples for show – which was no doubt fuelled by the imperial propaganda machine. In this context, the dedication of the church of St Stephen need not directly have followed the temple closure, as the inscriptions that record the dedication are undated and mention Theodore, who was bishop of Philae until after 577. Probably, then, the decision to turn the temple into a church was made by the bishop, in which a new purpose had to be found for an abandoned building. Viewing the reuse of the temple in more practical terms also ties in better with the architectural reconstruction by Peter Grossman, which indicates that rather than the naos, as was assumed by Nautin, the pronaos was turned into a three-aisled church.52 We have therewith placed the reuse of the temple of Isis in a local context rather than regarding it as a triumph of Christianity over still thriving Ancient Egyptian cults.53

A second, even less reliable literary source on the end of the cults at Philae exists in the form of the Coptic Life of Aaron. The Life, which describes events taking place in the fourth and early fifth century but was written down in the sixth century, contains an entertaining story of the first bishop of Philae, Macedonius (ca. 343). Having been freshly appointed by Bishop Athanasius in Alexandria, he travels south and enters the island, which is still dominated by idol worshippers, incognito. He approaches the altar where sacrifices are made and ambiguously asks the sons of the temple priest, who happens to be away on some business, to sacrifice to “God.” As the sons are preparing the fire, he goes to the cage where the sacred falcon is kept, takes it out, cuts off its head and throws the bird into the fire: thus the old god is sacrificed to the new God. At first, Macedonius has to flee but eventually a miracle results in the conversion of the entire island to Christianity. Since we know that the falcon cult was still practiced into the fifth century and the island only became Christian gradually, this story is purely legendary. On the other hand, it does have historical value as the perspective of a later, sixth-century audience on how its community had become Christian.54

Conclusion

We have discussed three cases that have been taken as exemplary for widespread religious violence in late antique Egypt or even for the pervasive nature of religious violence in the late antique world. Each of these three cases is well documented in Christian literature, and even secular literature (Eunapius, Procopius), which describes the violence in dramatic terms as a direct consequence of Christian – “pagan” conflict, thus seemingly confirming the picture that the fourth and fifth centuries saw a struggle between the old and the new religion, leading to Christian triumph.

As it now becomes more and more accepted in Late Antique Studies to dis-card the triumphalist overtones of our Christian sources and to view religious transformation as a gradual and complex process, in which violence only rarely erupted, these cases have been re-evaluated. It has been argued that, if we take away the emphasis on violence and take proper account of the other sources available (inscriptions, papyri, and material remains), it becomes clear that all three incidents occurred in specific local, socio-political circumstances: the Serapeum incident arose from the explosive situation in the capital, perhaps induced but not necessarily directly related to the imperial edict of June 391, the anti-“pagan” rhetoric of Shenoute needs to be seen in the context of his power struggle with the local elite and the closure of the Isis temple at Philae was probably no more than a propaganda stunt of Justinian’s that would have had a minimal effect on a local level. We have also seen that in each case, the literary sources speak of a “destruction” of temples and idols, whereas in reality the violence was something less extreme. At Philae there are no signs at all of destruction, whereas in Atripe the “destruction” by Shenoute could have consisted at most of starting a fire in an abandoned building. Finally, the Serapeum was not as thoroughly destroyed as suggested in the sources, although it is impossible to evaluate the extent to which initial damage was done. The impact of the event cannot be underestimated, how-ever, and was soon perceived as the total triumph of the Alexandrian church.

All in all, I hope that my project – by bridging the gap between the ideological discourse in the literature and the other sources, especially material remains, and by placing the incidents against a wider background of religious transformation – will put these and other events into their proper contexts. Rather than assuming widespread violence from the start, it will address the question why religious violence broke out at all and under what special circumstances. The resulting picture will not be one of a particularly violent society but it will provide clearer insights into why ancient authors used a violent discourse and what factors led to this rhetoric spilling over into reality. The powerful image of Agora can thus be discarded, but the much more complex reality behind it makes religious violence an all the more interesting phenomenon to study.

Appendix

Endnotes

- This painting is also briefly mentioned by T. Myrup Kristensen, Making and Breaking the Gods: Christian Responses to Pagan Sculpture in Late Antiquity, Aarhus Studies in Mediterranean Antiquity 12 (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013), 16.

- I mention here only A. Momigliano, ed., The Conflict Between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 1963), for the historical context of which see P. Brown, “Back to the Future: Pagans and Christians at the Warburg Institute in 1958,” in Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire: The Breaking of a Dialogue (IVth–VIth Century A.D.), ed. P. Brown and R. Lizzi Testa, Christianity and History 9 (Zurich: Lit and Piscataway, NJ: Transaction, 2011), 17–24.

- E.g. R. MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100–400) (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984); R. Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians (London: Viking, 1986); F.R. Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370–529, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 1993–1994); R. MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997); P. Chuvin, Chronique des derniers païens: La disparition du paganisme dans l’Empire romain, du règne de Constantin à celui de Justinien, 3rd ed. (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2009); É. Rebillard, Christians and Their Many Identities in Late Antiquity, North Africa, 200–450 CE (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012); C.P. Jones, Between Pagan and Christian (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- E.g. J. Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt: Studien zu den Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Christen, Heiden und Juden im Osten des Römischen Reiches (von Konstantin bis Theodosius II.), Klio Beihefte, Neue Folge 8 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2004); M. Gaddis, “There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ”: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire, Transformation of the Classical Heritage 39 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005); H.A. Drake, ed., Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006); J. Hahn, S. Emmel, and U. Gotter, eds., From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity, Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163 (Leiden: Brill, 2008); Th. Sizgorich, Violence and Belief in Late Antiquity: Militant Devotion in Christianity and Islam, Divinations (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009); P. Athanassiadi, Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive, Histoire (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2010); B. Isele, Kampf um Kirchen: Religiöse Gewalt, heiliger Raum und christliche Topographie in Alexandria und Konstantinopel (4. Jh.), Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband, Kleine Reihe 4 (Münster: Aschendorff, 2010); E.J. Watts, Riot in Alexandria: Tradition and Group Dynamics in Late Antique Pagan and Christian Communities, Transformation of the Classical Heritage 46 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010); J. Hahn, ed., Staat und religiöser Konflikt: Imperiale und lokale Verwaltung und die Gewalt gegen Heiligtümer in der Spätantike, Millennium-Studien 34 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011); B.D. Shaw, Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), with the discussion of this book by M.A. Tilley, D. Frankfurter, P. Frederiksen, and B.D. Shaw in Journal of Early Christian Studies 21 (2013): 291–309 and by C. Ando, C. Conybeare, C. Grey, N. Lenski, and H.A. Drake in Journal of Late Antiquity 6 (2013): 197–263; Kristensen, Making and Breaking the Gods.

- J. Assmann, Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008), and id., The Price of Monotheism, trans. R. Savage (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010).

- E.g. B. Rennie and P.L. Tite, eds., Religion, Terror, and Violence: Religious Studies Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2008); W.T. Cavenaugh, The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); J.N. Bremmer, “Religious Violence and Its Roots: A View from Antiquity,” Asdiwal 6 (2011): 71–9 (reprinted in the present volume); H. Kippenberg, Violence as Worship: Religious Wars in the Age of Globalization, trans. B. McNeil (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011); M. Juergensmeyer, M. Kitts, and M. Jerryson, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Violence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); S. Clarke, R. Powell, and J. Savulescu, eds., Religion, Intolerance, and Conflict: A Scientific and Conceptual Investigation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); S. Clarke, The Justification of Religious Violence, Blackwell Public Philosophy 15 (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2014); cf. also the launching of the Journal of Religion and Violence in 2013.

- W. Mayer, “Religious Conflict: Definitions, Problems and Theoretical Approaches,” in Religious Conflict from Early Christianity to the Rise of Islam, ed. W. Mayer and B. Neil, Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte 121 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013), 1–20; J.N. Bremmer, “Religious Violence Between Greeks, Romans, Christians and Jews,” in Violence in Early Christianity: Victims and Perpetrators, ed. A.-K. Geljon and R. Roukema, Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 125 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 8–30; see also W. Mayer’s contribution in this volume.

- E.g. S. Emmel, U. Gotter, and J. Hahn, “ ‘From Temple to Church’: Analysing a Late Antique Phenomenon of Transformation,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 1–22; R.S. Bagnall, “Models and Evidence in the Study of Religion in Late Antique Egypt,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 25–32; L. Lavan, “The End of the Temples: Towards a New Narrative?” in The Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism,” ed. L. Lavan and M. Mulryan, Late Antique Archaeology 7 (Leiden: Brill, 2011), xv–lxv.

- T.D. Barnes, Early Christian Hagiography and Roman History, Tria corda 5 (Tübin-gen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 199–234; A. Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 799.

- F.W. Deichmann, “Frühchristliche Kirchen in antiken Heiligtümern,” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 54 (1939): 105–36, repr. in Rom, Ravenna, Konstantinopel, Naher Osten: Gesammelte Studien zur spätantiken Architektur, Kunst und Geschichte (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1984), 56–94.

- E.g. B. Ward Perkins, “Reconfiguring Sacred Space: From Pagan Shrines to Christian Churches,” in Die spätantike Stadt und ihre Christianisierung, ed. G. Brands and H.-G. Severin, Spätantike – frühes Christentum – Byzanz: Kunst im ersten Jahrtausend, Reihe B, Studien und Perspektiven 11 (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2003), 285–90; R. Bayliss, Provincial Cilicia and the Archaeology of Temple Conversion, British Archaeological Reports International Series 1281 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2004); Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church; Lavan and Mulryan, Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism.”

- The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. As the examples mentioned thus far show, I shall clearly limit my topic to religious violence against the Ancient Egyptian religion, in particular temples, statues, and “pagans,” and not venture into intra-religious, Christian violence, which would require a separate project. For now, see e.g. Isele, Kampf um Kirchen, 113–92 on Alexandria.

- E.g. L. Kákosy, “Das Ende des Heidentums in Ägypten,” in Graeco-Coptica: Griechen und Kopten im byzantinischen Ägypten, ed. P. Nagel, Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Reihe I 29 (Halle: Martin-Luther-Universität, 1984), 61–76; E. Wipszycka, “La christianisation de l’Égypte aux IVe–VIesiècles. Aspects sociaux et ethniques,” Aegyptus 68 (1988): 117–65, repr. in Études sur le christianisme dans l’Égypte de l’Antiquité tardive, Studia Ephemeridis Augustinianum 52 (Rome: Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum, 1996), 63–105; L. Kákosy, “Probleme der Religion im römerzeitlichen Ägypten,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 18.5 (1995): 2894–3049; D. Frankfurter, Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), esp. 265–84, and “ ‘Things Unbefitting Christians’: Violence and Christianization in Fifth-Century Panopolis,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 8 (2000): 273–95; E. Sauer, The Archaeology of Religious Hatred in the Roman and Early Medieval World (Stroud: Tempus, 2003), esp. 89–101; D. Frankfurter, “Iconoclasm and Christianization in Late Antique Egypt: Christian Treatments of Space and Image,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 135–59.

- Frankfurter, Religion in Roman Egypt, 265.

- J.H.F. Dijkstra, Philae and the End of Ancient Egyptian Religion: A Regional Study of Religious Transformation (298–642 CE), Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 173 (Leuven: Peeters, 2008).

- J.H.F. Dijkstra, “The Fate of the Temples in Late Antique Egypt,” in Lavan and Mulryan, Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism,” 389–436, a shortened and adapted version of which appeared as “Das Schicksal der Tempel in der Spätantike,” in Kult-Orte. Mythen, Wissenschaft und Alltag in den Tempeln Ägyptens, ed. M.A. Stadler and D. von Recklinghausen (Berlin: Manetho, 2011), 201–17.

- Claudius’ letter to the Jews: P.Lond. VI 1912 = CPJ II 153. For the events of 38–41, see e.g. J.M.G. Barclay, Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora: From Alexander to Trajan (323 BCE–117 CE), Hellenistic Culture and Society 33 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), 48–71; E.S. Gruen, Diaspora: Jews Amidst Greeks and Romans (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 54–83; P.W. van der Horst, Philo’s Flaccus: The First Pogrom. Introduction, Translation and Commentary, Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series 2 (Leiden: Brill, 2003); K. Blouin, Le conflit Judéo-Alexandrin de 38–41: L’identité juive à l’épreuve, Collection Judaïsmes (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2005); A. Harker, Loyalty and Dissidence in Roman Egypt: The Case of the Acta Alexandrinorum (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 9–47; S. Gambetti, The Alexandrian Riots of 38 C.E. and the Persecution of the Jews: A Historical Reconstruction, Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 135 (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

- Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, 66–74.

- Eunapius, V. Soph. 6.107–13; in Eunape de Sardes. Vies de philosophes et de sophistes, ed. R. Goulet, 2 vols., Collection des universités de France. Série grecque 508 (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2014), 2:39–41; Rufinus, Hist. eccl. 11.22–23; in Eusebius Werke, ed. E. Schwartz and Th. Mommsen, vol. 2.2, GCS NF 6.2 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1999), 1025–30; Socrates, Hist. eccl. 5.16–17; in Sokrates Kirchengeschichte, ed. G.C. Hansen, GCS NF 1 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995), 289–91; Sozomen, Hist. eccl. 7.15.2–10; in Sozomenus Kirchengeschichte, ed. J. Bidez and G.C. Hansen, GCS NF 4 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995), 319–21; Theodoret, Hist. eccl. 5.22; in Theodoret Kirchengeschichte, ed. L. Parmentier, F. Scheidweiler, and G.C. Hansen, GCS NF 5 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1998), 320–1. 20 Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, 78–101, reiterated in J. Hahn, “The Conversion of the Cult Statues. The Destruction of the Serapeum 392 A.D. and the Transformation of Alexandria into the ‘Christ-Loving’ City,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 335–65.

- F. Thelamon, Païens et chrétiens au IVe siècle: l’apport de l’“Histoire ecclésiastique” de Rufin d’Aquilée (Paris: Études Augustiniennes, 1981).

- Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, 85–9, and “Conversion of the Cult Statues,” 345–8.

- Socrates, Hist. eccl. 5.16.1 (GCS NF 1.289).

- See the balanced overview of imperial policy on temples by J. Hahn, “Gesetze als Waffen? Die kaiserliche Religionspolitik und die Zerstörung von Tempel,” the concluding chapter (pp. 201–20) of the edited volume Staat und religiöser Konflikt, on which see the review by J.H.F. Dijkstra, Journal of Late Antiquity 6 (2013): 191–4. The first decree to advocate the destruction of temples is the one by Theodosius II in 435 (C.Th. 16.10.25).

- C.Th. 16.10.11. See e.g. T.D. Barnes, “Ammianus Marcellinus and His World,” Classical Philology 88 (1993): 61–2.

- As Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, 81–4; id., “Vetustus error extinctus est: Wann wurde das Sarapeion von Alexandria zerstört?” Historia 55 (2006): 371–4, and “Conversion of the Cult Statues,” 340–4, himself argues without, however, making a clear distinction between the improbable representation by Socrates, in which the imperial order determines the sequence of events and leads directly into the destruction of the Serapeum, and the more plausible versions of Rufinus and Sozomen. Cf. the excellent analysis by M. Errington, “Christian Accounts of the Religious Legislation of Theodosius I,” Klio 79 (1997): 423–8.

- Hahn, Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, 85–92, and “Conversion of the Cult Statues,” 347–52.

- See also Errington, “Christian Accounts,” 427–8.

- J.S. McKenzie, “Glimpsing Alexandria from Archaeological Evidence,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 16 (2003): 50–6; J.S. McKenzie, S. Gibson, and A.T. Reyes, “Reconstructing the Serapeum in Alexandria from the Archaeological Evidence,” Journal of Roman Studies 94 (2004): 73–121; J.S. McKenzie, The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700, Pelican History of Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 53–6, 195–203.

- McKenzie, Gibson, and Reyes, “Reconstructing the Serapeum,” 107–10; McKenzie, Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, 246.

- Sozomen, Hist. eccl. 7.15.10 (GCS NF 4.321.19–20).

- Rufinus, Hist. eccl. 11.27 (GCS NF 6.1033.16–17).

- Dijkstra, “Fate of the Temples,” 399.

- Hahn, “Wann wurde das Sarapeion.”

- Evagrius is mentioned in the accounts of Eunapius, V. Soph. 6.108 (Goulet, 40.5) and Sozomen, Hist. eccl. 7.15.5 (GCS NF 4.320.16) and was succeeded by Hypatius on 9 April 392, as appears from C.Th. 11.36.1 = C.J. 1.4.6. See PLRE I s.v. Evagrius 7 (p. 286) and Hypatius 3 (p. 448).

- R.W. Burgess and J.H.F. Dijkstra, “The ‘Alexandrian World Chronicle’, Its Consulariaand the Date of the Destruction of the Serapeum (with an Appendix on the Praefecti Augustales),” Millennium 10 (2013): 39–113, esp. 96–102, and the summary by J.H.F. Dijkstra, “The ‘Alexandrian World Chronicle’: Place in the Late Antique Chronicle Traditions, Date and Historical Implications,” in Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of Papyrology, ed. T. Derda, A. Łajtar, and J. Urbanik, 3 vols., Journal of Juristic Papyrology Supplements 28 (Warsaw: Faculty of Law and Administration and Institute of Archaeology, Department of Papyrology, Warsaw University and Taubenschlag Foundation, 2016), 1:535–47.

- J. Leipoldt, Schenute von Atripe und die Entstehung des national ägyptischen Christen-tums, Texte und Untersuchungen, Neue Folge 10.1 (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1903), 175: “Die Kopten seiner Zeit hatten aber nur eine Leidenschaft: das war der Haß gegen die ‘Hellenen’, die Heiden. Und diesen Haß hat Schenute rastlos geschürt, hat aus ihm die lodernde Flamme erweckt, die einen Göttertempel nach dem anderen einäscherte” (my translation).

- D.N. Bell, Besa, the Life of Shenoute, Cistercian Studies 73 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1983), 9. Cf. A.G. López, Shenoute of Atripe and the Uses of Poverty: Rural Patronage, Religious Conflict, and Monasticism in Late Antique Egypt, Transformation of the Classical Heritage 50 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013), 2 who cites this passage but without mentioning that Bell paraphrases É. Amélineau, Les moines égyptiens: Vie de Schnoudi, Annales du Musée Guimet. Bibliothèque de vulgarisation 1 (Paris: Leroux, 1889), 58: “Un volcan n’est jamais plus beau que lorsqu’il vomit le feu, les cendres et les laves. Le spectacle est imposant, mais il est horrible et malsain.”

- See esp. S. Emmel, Shenoute’s Literary Corpus, 2 vols., CSCO 599, 600 (Leuven: Peeters, 2004).

- S. Emmel, “Shenoute of Atripe and the Christian Destruction of Temples in Egypt: Rhetoric and Reality,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 161–201. See also Dijkstra, “Fate of the Temples,” 396–7, and “ ‘I Wish to Offer a Sacrifice to God Today’: The Discourse of Idol Destruction in the Coptic Life of Aaron,” Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 7 (2015): 67–8.

- Leipoldt, Schenute von Atripe, 92–3, with n. 1. This view is still found e.g. in P. Grossmann, “Tempel als Ort des Konflikts in christlicher Zeit,” in Le temple, lieu de conflit, ed. P. Borgeaud et al., Les Cahiers du Centre d’étude du Proche-Orient ancien 7 (Leuven: Peeters, 1994), 190, and Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, Handbuch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung, Nahe und der Mittlere Osten 62 (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 171, 532.

- R. el-Sayed, “Schenute und die Tempel von Atripe: Zur Umnutzung des Triphis-bezirks in der Spätantike,” in Honi soit qui mal y pense. Studien zum pharaonischen, griechisch-römischen und spätantiken Ägypten zu Ehren von Heinz-Josef Thissen, ed. H. Knuf, C. Leitz, and D. von Recklinghausen, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 194 (Leuven: Peeters, 2010), 519–38; D. Klotz, “Triphis in the White Monastery: Reused Temple Blocks from Sohag,” Ancient Society 40 (2010): 197–213; R. el-Sayed and Y. el-Masry. Athribis I. General Site Survey 2003–2007; Archaeological & Conservation Studies; the Gate of Ptolemy IX: Architecture and Inscriptions, 2 vols. (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 2012), 1:24–9.

- López, Shenoute of Atripe and the Uses of Poverty, 102–26, with the review of this book by J.H.F. Dijkstra, Vigiliae Christianae 69 (2015): 97–101.

- For text and translation of this work, known by its incipit as Let Our Eyes, see Emmel, “Shenoute of Atripe and the Christian Destruction of Temples in Egypt,” 182–97. For a discussion of Shenoute’s raids on Gessios’ house, see the same article, pp. 166–81.

- E.g. R.S. Bagnall, Egypt in Late Antiquity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 264.

- Procopius, Pers. 1.19.36–37; translation: T. Eide et al., Fontes Historiae Nubiorum. Vol. III: From the First to Sixth Century AD (Bergen: University of Bergen, Department of Greek, Latin and Egyptology, 1998), 1191 (no. 328), adapted.

- I.Philae II 200–204; quoted here is no. 201.

- P. Nautin, “La conversion du temple de Philae en église chrétienne,” Cahiers archéologiques 17 (1967): 1–43 (quote at p. 16: “désormais l’île entière était aux chrétiens”), essentially followed e.g. by J. Hahn, “Die Zerstörung der Kulte von Philae: Geschichte und Legende am ersten Nilkatarakt,” in Hahn, Emmel and Gotter, From Temple to Church, 203–42.

- Emmel, Gotter and Hahn, “ ‘From Temple to Church,’ ” 12: “possibly Philae represents the only completely unambiguous case of an immediate take-over in cultic use from an active pagan temple to a regular church.”

- E.g. Nautin, “Conversion du temple de Philae en église chrétienne,” 7; Hahn, “Zer-störung der Kulte von Philae,” 204–5.

- I.Philae II 199.

- P. Grossmann, “Die Kirche des Bischofs Theodoros im Isistempel von Philae: Ver-such einer Rekonstruktion,” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 58 (1984): 107–17, “Tempel als Ort des Konflikts,” 194, and Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, 47. Pace Nautin, “Conversion du temple de Philae en église chrétienne,” 27–9, 34–43.

- For a full analysis, see Dijkstra, Philae and the End, with the summaries/updates in “Fate of the Temples,” 421–30, and “Philae,” Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum 27 (2015): 574–91.

- I am currently preparing a new critical edition of this work, together with J. van der Vliet, for the announcement of which, see J.H.F. Dijkstra, “Monasticism on the South-ern Egyptian Frontier in Late Antiquity: Towards a New Critical Edition of the Coptic Life of Aaron,” Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 5 (2013): 31–47. For the passage of Macedonius and the holy falcon of Philae, see now Dijkstra, “‘I Wish to Offer a Sacrifice to God Today,’” which also places it in the context of other stories of idol destruction in Egyptian hagiographical literature.

Bibliography

- Amélineau, É. Les moines égyptiens: Vie de Schnoudi. Annales du Musée Guimet. Bibliothèque de vulgarisation 1. Paris: Leroux, 1889.

- Assmann, J. The Price of Monotheism. Translated by R. Savage. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.

- ———. Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008.

- Athanassiadi, P. Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive. Histoire. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2010.

- Bagnall, R.S. “Models and Evidence in the Study of Religion in Late Antique Egypt.” Pages 23–41 in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- ———. Egypt in Late Antiquity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Barclay, J.M.G. Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora. From Alexander to Trajan (323 BCE–117 CE). Hellenistic Culture and Society 33. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996.

- Barnes, T.D. Early Christian Hagiography and Roman History. Tria corda 5. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010.

- ———. “Ammianus Marcellinus and His World.” Classical Philology 88 (1993): 55–70.

- Bayliss, R. Provincial Cilicia and the Archaeology of Temple Conversion. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1281. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2004.

- Bell, D.N. Besa, the Life of Shenoute. Cistercian Studies 73. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1983.

- Bidez, J. and G.C. Hansen, eds. Sozomenus Kirchengeschichte. GCS NF 4. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995.Blouin, K. Le conflit Judéo-Alexandrin de 38–41: L’identité juive à l’épreuve. Collection Judaïsmes. Paris: L’ Harmattan, 2005.

- Bremmer, J.N. “Religious Violence between Greeks, Romans, Christians and Jews.” Pages 8–30 in Violence in Early Christianity: Victims and Perpetrators. Edited by A.-K. Geljon and R. Roukema. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 125. Leiden: Brill, 2014

- ———. “Religious Violence and Its Roots: A View from Antiquity.” Asdiwal 6 (2011): 71–9.

- Brown, P. “Back to the Future: Pagans and Christians at the Warburg Institute in 1958.” Pages 17–24 in Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire: The Breaking of a Dialogue (IVth – VIth Century A.D.). Edited by P. Brown and R. Lizzi Testa. Christianity and History 9. Zurich: Lit and Piscataway, NJ: Transaction, 2011.

- Burgess, R.W. and Dijkstra, J.H.F. “The ‘Alexandrian World Chronicle’, Its Consulariaand the Date of the Destruction of the Serapeum (with an Appendix on the Praefecti Augustales).” Millennium 10 (2013): 39–113.

- Cameron, A. The Last Pagans of Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Cavenaugh, W.T. The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Chuvin, P. Chronique des derniers païens. La disparition du paganisme dans l’Empire romain, du règne de Constantin à celui de Justinien. 3rd ed. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2009.

- Clarke, S. The Justification of Religious Violence. Blackwell Public Philosophy 15. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

- Clarke, S., R. Powell, and J. Savulescu, eds. Religion, Intolerance, and Conflict: A Scientific and Conceptual Investigation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Deichmann, F.W. “Frühchristliche Kirchen in antiken Heiligtümern.” Jahrbuch des deutschen archäologischen Instituts 54 (1939): 105–36. Repr. pages 56–94 in Rom, Ravenna, Konstantinopel, Naher Osten. Gesammelte Studien zur spätantiken Architektur, Kunst und Geschichte. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1984.

- Dijkstra, J.H.F. “The ‘Alexandrian World Chronicle’: Place in the Late Antique Chronicle Traditions, Date and Historical Implications.” Pages 535–47 in Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of Papyrology. Edited by T. Derda, A. Łajtar, J. Urbanik and G. Ochała. 3 vols. Journal of Juristic Papyrology Supplements 28. Warsaw: Faculty of Law and Administration and Institute of Archaeology, Department of Papyrology, Warsaw University and Taubenschlag Foundation, 2016.

- ———. “ ‘I Wish to Offer a Sacrifice to God Today’: The Discourse of Idol Destruction in the Coptic Life of Aaron.” Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 7 (2015): 61–75.

- ———. “Philae.” Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum 27 (2015): 574–91.

- ———. “Religiöse Gewalt im spätantiken Ägypten.” Pages 80–83 in Ein Gott: Abrahams Erben am Nil. Juden, Christen und Muslime in Ägypten von der Antike bis zum Mittelalter. Edited by C. Fluck, G. Helmecke, and E.R. O’Connell. Petersberg: Imhof, 2015.

- ———. “Religious Violence in Late Antique Egypt.” Pages 78 – 81 in Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs. Edited by C. Fluck, G. Helmecke and E.R. O’Connell. London: British Museum Press, 2015.

- ———. Review of A.G. Lόpez, Shenoute of Atripe and the Uses of Poverty. Vigiliae Christianae 59 (2015): 97–101.

- ———. “Monasticism on the Southern Egyptian Frontier in Late Antiquity: Towards a New Critical Edition of the Coptic Life of Aaron.” Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 5 (2013): 31–47.

- ———. Review of J. Hahn, ed., Staat und religiöser Konflikt. Journal of Late Antiquity 6 (2013): 191–4.

- ———. “Das Schicksal der Tempel in der Spätantike.” Pages 201–17 in KultOrte. Mythen, Wissenschaft und Alltag in den Tempeln Ägyptens. Edited by M.A. Stadler and D. von Recklinghausen. Berlin: Manetho, 2011.

- ———. “The Fate of the Temples in Late Antique Egypt.” Pages 389–436 in The Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism.” Edited by L. Lavan and M. Mulryan. Late Antique Archaeology 7. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

- ———. Philae and the End of Ancient Egyptian Religion: A Regional Study of Religious Transformation (298–642 CE). Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 173. Leuven: Peeters, 2008.

- Drake, H.A., ed. Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices. Aldershot and Burlington: Variorum, 2006.

- Eide, T., T. Hägg, R.H. Pierce, and L.T. Török. Fontes Historiae Nubiorum. Vol. III: From the First to Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen, Department of Greek, Latin and Egyptology, 1998.

- Emmel, S. “Shenoute of Atripe and the Christian Destruction of Temples in Egypt: Rhetoric and Reality.” Pages 161–201 in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- ———. Shenoute’s Literary Corpus. 2 vols. CSCO 599, 600. Leuven: Peeters, 2004.

- Emmel, S., U. Gotter, and J. Hahn. “ ‘From Temple to Church’: Analysing a Late Antique Phenomenon of Transformation.” Pages 1–22 in From Temple to Church. Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- Errington, M. “Christian Accounts of the Religious Legislation of Theodosius I.” Klio 79 (1997): 398–443.

- Frankfurter, D. “Iconoclasm and Christianization in Late Antique Egypt: Christian Treatments of Space and Image.” Pages 135–59 in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- ———. “ ‘Things Unbefitting Christians’: Violence and Christianization in Fifth-Century Panopolis.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 8 (2000): 273–95.

- ———. Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gaddis, M. “There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ”: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire. Transformation of the Classical Heritage 39. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005.

- Gambetti, S. The Alexandrian Riots of 38 C.E. and the Persecution of the Jews: A Historical Reconstruction. Journal for the Study of Judaism Supplements 135. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

- Goulet, R., ed. Eunape de Sardes: Vies de philosophes et de sophistes. 2 vols. Collection des universités de France. Série grecque 508. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2014.

- Grossmann, P. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten. Handbuch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung, Nahe und der Mittlere Osten 62. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- ———. “Tempel als Ort des Konflikts in christlicher Zeit.” Pages 181–201 in Le temple, lieu de conflit. Edited by P. Borgeaud et al. Les Cahiers du Centre d’étude du Proche-Orient ancien 7. Leuven: Peeters, 1994.

- ———. “Die Kirche des Bischofs Theodoros im Isistempel von Philae. Versuch einer Rekonstruktion.” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 58 (1984): 107–17.

- Gruen, E.S. Diaspora: Jews amidst Greeks and Romans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-versity Press, 2002.

- Hahn, J.“Gesetze als Waffen? Die kaiserliche Religionspolitik und die Zerstörung von Tempel.” Pages 201–220 in Staat und religiöser Konflikt. Imperiale und lokale Verwaltung und die Gewalt gegen Heiligtümer in der Spätantike. Edited by J. Hahn. Millennium-Studien 34. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011.

- ———. ed. Staat und religiöser Konflikt: Imperiale und lokale Verwaltung und die Gewalt gegen Heiligtümer in der Spätantike. Millennium-Studien 34. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011.

- ———. “The Conversion of the Cult Statues: The Destruction of the Serapeum 392 A.D. and the Transformation of Alexandria into the ‘Christ-Loving’ City.” Pages 335–65 in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- ———. “Die Zerstörung der Kulte von Philae: Geschichte und Legende am ersten Nilkatarakt.” Pages 203–42 in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cul-tic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by J. Hahn, S. Emmel and U. Gotter. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- ———. “Vetustus error extinctus est. Wann wurde das Sarapeion von Alexandria zerstört?” Historia 55 (2006): 368–83.

- ———. Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt: Studien zu den Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Christen, Heiden und Juden im Osten des Römischen Reiches (von Konstantin bis Theodosius II.). Klio Beihefte, Neue Folge 8. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2004.

- Hahn, J., S. Emmel, and U. Gotter, eds. From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 163. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- Hansen, G.C., ed. Sokrates Kirchengeschichte. GCS NF 1. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995.

- Harker, A. Loyalty and Dissidence in Roman Egypt: The Case of the Acta Alexandrinorum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Horst, P.W. van der. Philo’s Flaccus: The First Pogrom. Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series 2. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

- Isele, B. Kampf um Kirchen: Religiöse Gewalt, heiliger Raum und christliche Topographie in Alexandria und Konstantinopel (4. Jh.). Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergän-zungsband, Kleine Reihe 4. Münster: Aschendorff, 2010.

- Jones, C.P. Between Pagan and Christian. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Juergensmeyer, M., M. Kitts and M. Jerryson, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Kákosy, L. “Probleme der Religion im römerzeitlichen Ägypten.” Pages 2894–3049 in Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt, part II, 18.5. Edited by H. Temporini and W. Haase. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995.

- ———. “Das Ende des Heidentums in Ägypten.” Pages 61–76 in Graeco-Coptica. Griechen und Kopten im byzantinischen Ägypten. Edited by P. Nagel. Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Reihe I 29. Halle: Martin-Luther-Universität, 1984.

- Kippenberg, H. Violence as Worship: Religious Wars in the Age of Globalization. Translated by B. McNeil. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

- Klotz, D. “Triphis in the White Monastery: Reused Temple Blocks from Sohag.” Ancient Society 40 (2010): 197–213.

- Lane Fox, R. Pagans and Christians. London: Viking, 1986.

- Lavan, L. “The End of the Temples: Towards a New Narrative?” Pages xv–lxv in The Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism.” Edited by L. Lavan and M. Mulryan. Late Antique Archaeology 7. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

- Lavan, L. and M. Mulryan, eds. The Archaeology of Late Antique “Paganism.” Late Antique Archaeology 7. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

- Leipoldt, J. Schenute von Atripe und die Entstehung des national ägyptischen Christen-tums. Texte und Untersuchungen, Neue Folge 10.1. Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1903.

- López, A.G. Shenoute of Atripe and the Uses of Poverty: Rural Patronage, Religious Conflict, and Monasticism in Late Antique Egypt. Transformation of the Classical Heritage 50. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.

- MacMullen, R. Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

- ———. Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100–400). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984.

- Mayer, W. “Religious Conflict: Definitions, Problems and Theoretical Approaches.” Pages 1–20 in Religious Conflict from Early Christianity to the Rise of Islam. Edited by W. Mayer and B. Neil. Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte 121. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013.

- McKenzie, J.S. The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700. Pelican History of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

- ———. “Glimpsing Alexandria from Archaeological Evidence.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 16 (2003): 35–63.

- McKenzie, J.S., S. Gibson, and A.T. Reyes, “Reconstructing the Serapeum in Alexandria from the Archaeological Evidence.” Journal of Roman Studies 94 (2004): 73–121.

- Momigliano, A., ed. The Conflict between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century. Oxford: Clarendon, 1963.

- Nautin, P. “La conversion du temple de Philae en église chrétienne.” Cahiers Archéologiques 17 (1967): 1–43.

- Parmentier, L., F. Scheidweiler, and G.C. Hansen, eds. Theodoret Kirchengeschichte. GCS NF 5. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1998.

- Rebillard, É. Christians and Their Many Identities in Late Antiquity, North Africa, 200–450 CE. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012.

- Rennie, B. and P.L. Tite, eds. Religion, Terror, and Violence: Religious Studies Perspectives. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Sauer, E. The Archaeology of Religious Hatred in the Roman and Early Medieval World. Stroud: Tempus, 2003.

- el-Sayed, R. “Schenute und die Tempel von Atripe. Zur Umnutzung des Triphisbezirks in der Spätantike.” Pages 519–38 in Honi soit qui mal y pense. Studien zum pharaonischen, griechisch-römischen und spätantiken Ägypten zu Ehren von Heinz-Josef Thissen. Edited by H. Knuf, C. Leitz, and D. von Recklinghausen. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 194. Leuven: Peeters, 2010.

- el-Sayed, R. and Y. el-Masry. Athribis I. General Site Survey 2003–2007; Archaeological & Conservation Studies; the Gate of Ptolemy IX: Architecture and Inscriptions. 2 vols. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 2012.

- Schwartz, E. and Th. Mommsen, eds. Eusebius Werke, vol. 2.2. GCS NF 6.2. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1999.

- Shaw, B. Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Sizgorich, Th. Violence and Belief in Late Antiquity: Militant Devotion in Christianity and Islam. Divinations. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- Thelamon, F. Païens et chrétiens au IVe siècle: l’apport de l’“Histoire ecclésiastique” de Rufin d’Aquilée. Paris: Études Augustiniennes, 1981.

- Trombley, F.R. Hellenic Religion and Christianization, c. 370–529. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1993–1994.

- Ward Perkins, B. “Reconfiguring Sacred Space: From Pagan Shrines to Christian Churches.” Pages 285–90 in Die spätantike Stadt und ihre Christianisierung. Edited by G. Brands and H.-G. Severin. Spätantike – frühes Christentum – Byzanz: Kunst im ersten Jahrtausend. Reihe B, Studien und Perspektiven 11. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2003.

- Watts, E.J. Riot in Alexandria: Tradition and Group Dynamics in Late Antique Pagan and Christian Communities. Transformation of the Classical Heritage 46. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010.

- Wipszycka, E. “La christianisation de l’Égypte aux IVe – VIe siècles. Aspects sociaux et ethniques.” Aegyptus 68 (1988): 117–65. Repr. pages 63–105 in Études sur le chris-tianisme dans l’Égypte de l’Antiquité tardive. Studia Ephemeridis Augustinianum 52. Rome: Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum, 1996.

Chapter 9 (211-233) from Reconceiving Religious Conflict: New Views from the Formative Years of Christianity, edited by Wendy Mayer and Chris L. de Wet (Routledge, 01.25.2018), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.