The history of tax avoidance is a history of inequality made durable not by failure, but by design. It is a testament to the quiet power of legal craft, political lobbying, and bureaucratic opacity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Wealth Without Burden

In the long arc of American capitalism, few figures loom larger in popular imagination than the robber barons. Draped in opulence, immortalized in steel, rail, and oil, they embodied both the promise and peril of industrial modernity. Yet amid the grandeur of their fortunes lies a quieter, more persistent pattern, one that threads through courtrooms, legislatures, and backroom deals: the evasion of taxes.

Tax avoidance by the wealthiest Americans is no recent innovation. It is a tradition, crafted in boardrooms, shielded by legal fictions, and consecrated through policy. From the tycoons of the Gilded Age to the multinational moguls of the twenty-first century, the richest have often succeeded in converting political influence into financial immunity. To study this phenomenon is to peer into the hidden architecture of power, one where wealth not only escapes redistribution but evades the very scrutiny meant to make it legible.

What follows is a historical excavation of this architecture, tracing its foundations in the Gilded Age, its mutation through the New Deal, its globalization in the late twentieth century, and its entrenchment in the digital economy. Tax evasion is not merely an economic story. It is a political act, a cultural performance, and a structural wound in the democratic body.

Gilded Veils: The Taxless Empire of the 19th-Century Tycoon

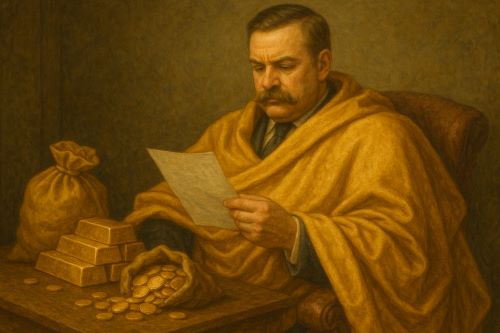

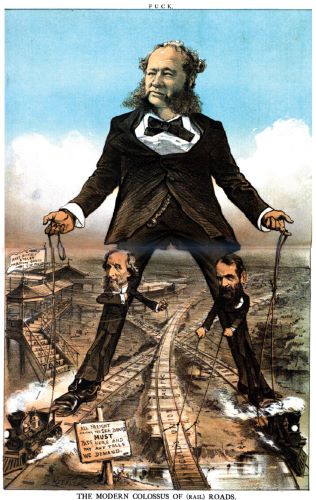

The term “robber baron” was first popularized in the late nineteenth century, borrowed from medieval German nobles who extracted tolls from travelers without offering protection or service. In America, the label attached itself to men like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Cornelius Vanderbilt. Their wealth derived from the extraction and control of resources – oil, steel, railroads, and finance. But just as crucially, it was protected and multiplied through deliberate tax avoidance.1

Until the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, the United States had no permanent federal income tax. The Civil War income tax expired in 1872, and from then until the early twentieth century, the federal government relied heavily on tariffs and excise taxes, regressive mechanisms that burdened the poor more than the rich.2 This structure allowed industrialists to accumulate wealth largely free of federal obligation.

Carnegie and Rockefeller, often lionized for their philanthropy, made their fortunes under conditions of minimal taxation. When Carnegie donated libraries, he did so with pre-tax dollars. Rockefeller, master of the trust and the holding company, built an empire where legal form allowed economic substance to disappear behind layers of incorporation.3 These mechanisms were not illegal, but they reveal how deeply entwined corporate innovation was with the avoidance of fiscal responsibility.

Moreover, the political influence of these magnates shaped the very tax architecture that favored them. The defeat of the 1894 income tax, struck down in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., was widely celebrated by elite financial circles.4 For nearly two more decades, American plutocracy remained largely untaxed.

The Progressive Response: Tax Reform and The Birth of Modern Fiscal Policy

The ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913 was not a technical adjustment. It was a political rupture. Progressive reformers, incensed by the disparities of the Gilded Age, demanded a mechanism to redistribute wealth and constrain monopolistic power. The federal income tax, once unthinkable, became the linchpin of a new social compact.5

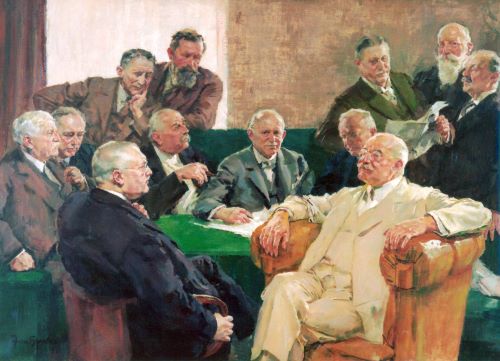

Initially modest in scope, the income tax grew quickly, especially during wartime. By the 1920s and 1930s, marginal rates on the wealthiest Americans reached staggering levels, over 70 percent at their peak. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration saw taxation as a moral and civic duty. In a 1935 address, he famously declared, “The process of the concentration of wealth…has reached such proportions that government must intervene.”6

Yet even in this golden age of progressive taxation, avoidance persisted. Wealthy individuals and corporations employed legal shelters, lobbied for deductions, and restructured holdings to minimize exposure. The DuPonts, Mellons, and other dynasties created complex trusts and family foundations, allowing intergenerational wealth transfer with minimal tax consequences.7

The creation of the Board of Tax Appeals in 1924 (later the Tax Court) and the expansion of the Internal Revenue Service reflected attempts to professionalize enforcement. But enforcement was always constrained by political pressure. Tax law, unlike criminal law, was shaped not only in courts but in committee rooms, where loopholes were often inserted by the very people who stood to benefit from them.

Offshore Frontiers and Legal Alchemy in the Postwar Era

By the mid-twentieth century, tax avoidance took on new dimensions. The rise of multinational corporations allowed firms to shift profits across borders, taking advantage of differential tax regimes. Jurisdictions like the Bahamas, Switzerland, and the Netherlands became havens not for criminals, but for corporations and heirs. As one commentator noted in the 1960s, “the rich have not stopped paying taxes—they have merely changed where their income is.”8

The postwar decades saw the emergence of a professional tax avoidance industry. Lawyers and accountants no longer merely prepared returns; they engineered transactions. Transfer pricing, offshore subsidiaries, and synthetic leases became tools not of productive investment but of fiscal invisibility. General Motors, IBM, and later Apple and Google developed structures so intricate that profits appeared in low-tax jurisdictions while operations remained in high-tax ones.9

Meanwhile, capital gains became a central battleground. While wages were taxed at high rates, investment income received preferential treatment. This disparity, embedded in the Internal Revenue Code since the 1920s, widened in the 1980s under Reagan-era reforms. “Trickle-down” theory masked a deeper reality: income from labor was taxed, income from wealth was massaged.10

Efforts to close loopholes, such as the Tax Reform Act of 1986, were often followed by waves of innovation that created new ones. In this sense, tax policy has been a game of cat and mouse, where the mouse hires better lawyers.11

The Digital Age: Invisible Wealth in the Information Economy

The Apple case is illustrative. Through a structure dubbed the “Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich,” Apple routed royalties through Irish and Dutch subsidiaries to ultimately deposit untaxed earnings in Caribbean shell companies.12 While such schemes have since been targeted by international regulators, they exemplify the agility of corporate strategy when confronted with regulatory friction. The game, it seems, is to stay a step ahead, not necessarily to abide, but to anticipate and outmaneuver.

Jeff Bezos’s Amazon, despite controlling vast logistical infrastructure within U.S. borders, reported no federal tax liability in several years of record profits.13 Facebook (now Meta) similarly employed IP migration to tax havens, routing advertising revenue through Ireland while keeping most of its engineering and platform development in the United States. These arrangements have been entirely legal, but legality here is not exoneration. It is evidence of complicity between legislative design and corporate ambition.

Moreover, the culture of wealth concealment has migrated downstream. The same offshore techniques once reserved for oil tycoons and steel magnates are now packaged and sold to upper-middle-class investors through “dynasty trusts,” “intentionally defective grantor trusts,” and shell LLCs registered in South Dakota or Delaware.14 The architecture of evasion, once bespoke and clandestine, has become normalized and institutional.

Conclusion: The Unseen Public Burden

To trace the history of tax avoidance by America’s wealthiest is not to discover a series of isolated infractions, but to map a pattern of structural exemption. From the railroad barons of the Gilded Age to the data barons of Silicon Valley, the trajectory is not one of increasing accountability but of increasing abstraction, where wealth becomes harder to see, harder to define, and harder to tax.

This pattern has been reinforced by a recurring moral logic: that the rich, by virtue of their philanthropy or innovation, contribute in ways more valuable than taxes could ever account for. Rockefeller endowed the University of Chicago. Gates funds vaccine research. Yet such private beneficence should not be mistaken for public contribution. Taxes are not charity. They are civic obligation.

The history of tax avoidance is a history of inequality made durable not by failure, but by design. It is a testament to the quiet power of legal craft, political lobbying, and bureaucratic opacity. What has been evaded is not merely revenue, but accountability. And in that evasion, the robber barons, then and now, have continued to shape the nation in their image: gilded, efficient, and hollow at the core.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Matthew Josephson, The Robber Barons: The Great American Capitalists, 1861–1901 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1934), 22.

- W. Elliot Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 40–43.

- Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (New York: Random House, 1998), 370.

- Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895).

- Steven R. Weisman, The Great Tax Wars: Lincoln to Wilson—The Fierce Battles over Money and Power That Transformed the Nation (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 264.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Message to Congress on Tax Revision,” June 19, 1935, in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, ed. Samuel I. Rosenman (New York: Random House, 1938), 274–75.

- Richard Tedlow, The Rise of the American Business Corporation (New York: Norton, 2001), 213–15.

- Ferdinand Lundberg, The Rich and the Super-Rich: A Study in the Power of Money Today (New York: Lyle Stuart, 1968), 385.

- Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World (London: Bodley Head, 2011), 88–92.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 180.

- Gabriel Zucman, The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 45–47.

- Jesse Drucker and Simon Bowers, “After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits,” The New York Times, November 6, 2017.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Amazon’s Tax Bill: $0,” February 13, 2019, https://itep.org/amazons-tax-bill-0/.

- Chuck Collins and Josh Hoxie, Billionaire Bonanza: The Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us (Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies, 2015), 29–31.

Bibliography

- Brownlee, W. Elliot. Federal Taxation in America: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. New York: Random House, 1998.

- Collins, Chuck, and Josh Hoxie. Billionaire Bonanza: The Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies, 2015.

- Drucker, Jesse, and Simon Bowers. “After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits.” The New York Times, November 6, 2017.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “Amazon’s Tax Bill: $0.” February 13, 2019. https://itep.org/amazons-tax-bill-0/.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons: The Great American Capitalists, 1861–1901. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1934.

- Lundberg, Ferdinand. The Rich and the Super-Rich: A Study in the Power of Money Today. New York: Lyle Stuart, 1968.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, edited by Samuel I. Rosenman. New York: Random House, 1938.

- Shaxson, Nicholas. Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World. London: Bodley Head, 2011.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. New York: W. W. Norton, 2012.

- Tedlow, Richard. The Rise of the American Business Corporation. New York: Norton, 2001.

- Weisman, Steven R. The Great Tax Wars: Lincoln to Wilson—The Fierce Battles over Money and Power That Transformed the Nation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

- Zucman, Gabriel. The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.