How this turbulent decade ushered in a new era for labor, culture, and government.

Government Response

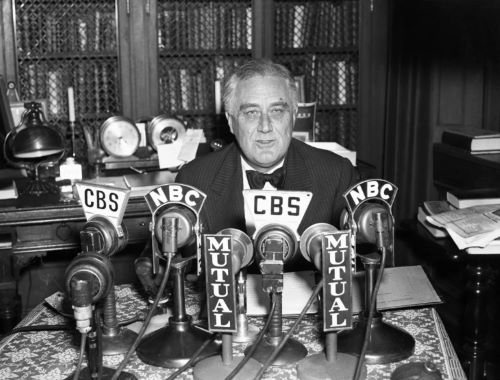

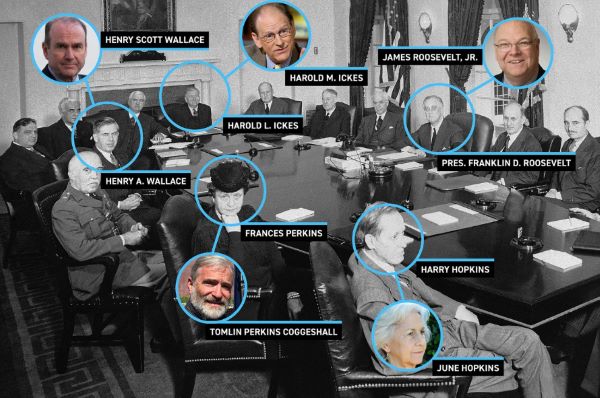

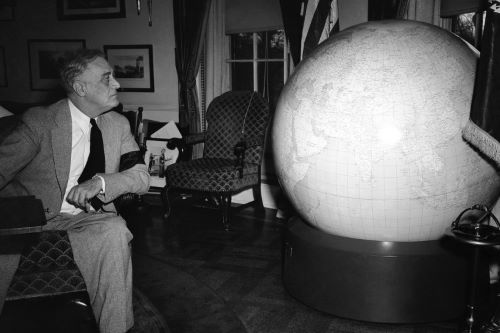

F.D.R. Didn’t Just Fix the Economy

He saved democracy itself.

The New Deal was more than a recovery program for the economy. It was, as the historian Eric Rauchway argues in his new book, “Why the New Deal Matters,” a recovery program for American democracy.

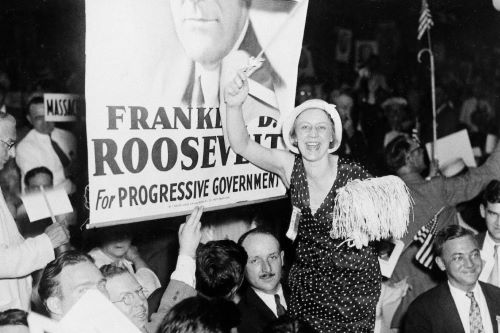

“I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people,” Franklin Roosevelt declared at the 1932 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Roosevelt had broken tradition to accept his party’s nomination and deliver a speech in person. And in that speech, he promised a program based on the “simple moral principle” that the “welfare and the soundness of a nation depend first upon what the great mass of the people wish and need” and second on “whether or not they are getting it.”

Aware of the challenge ahead of him should he win the presidency — nearly a quarter of Americans were out of work and the economy was shrinking by double digits — Roosevelt concluded his address with a call to action. “Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage,” he said. “This is more than a political campaign; it is a call to arms. Give me your help, not to win votes alone, but to win in this crusade to restore America to its own people.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

FDR’s Second 100 Days Were Cooler Than His First 100 Days

Let’s talk about the period when Roosevelt actually created the modern welfare state.

We have now made it past Joe Biden’s first 100 days in office, the traditional point at which political journalists pass sage judgment on the early results of a new presidency (or at least tap out a few saved-up think pieces in need of a hook). The country owes this practice to Franklin Roosevelt, who in July of 1933 sat down for one of his early fireside chats and told radio listeners that he wanted to reflect on “the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.” Reporters have been using it as a benchmark for taking stock ever since.

Does the custom still make any sense today? Maybe. Some research has found that presidents really have had more success passing legislation during their first 100 days than later on, possibly because they have tended to enjoy a moment of bipartisan approval early in their terms. These honeymoon periods might be thing of the past, however, thanks to increasing partisan polarization, which means the first three months might not matter in quite the same way they used to.

But whether or not it makes practical sense, marking the first 100 days bugs me purely from the standpoint of historical appreciation. FDR’s first 100 Days, momentous as they were, are arguably a tiny bit overrated in the popular imagination. And the focus on them obscures the fact that Roosevelt truly cemented his domestic legacy in a period known as the Second 100 Days—which took place two years later, in 1935. That’s when we got little things like Social Security and the foundation of modern labor law. The commentating class basically ignores that stretch, rather than think about what lessons it might hold.

Roosevelt’s first 100 days were really the disaster-response period of his presidency, the moment when the new chief executive grabbed the fire hose and started putting out the flames that had not just engulfed the economy—around a quarter of Americans were unemployed, with the share in some cities vastly higher—but were threatening to destroy the foundations of capitalism. After taking the oath of office in March, he called a special three-month session of Congress, which proceeded to pass some 76 pieces of legislation.

FDR’s achievements in this period were substantial. He successfully halted a spiraling financial crisis by declaring a national bank holiday, and signed reforms to prevent future meltdowns. He freed the U.S. from the shackles of the gold standard, legalized beer (cheers!), stood up public works and relief agencies, rescued rural America with farm subsidies, launched a massive regional development effort by creating the Tennessee Valley Authority, and much more. Though it would ultimately take the industrial frenzy of World War II to restore full prosperity to the United States, the economy did begin to heal and the sense of impending calamity faded.

That Time America Almost Had a 30-Hour Workweek

A six-hour workday could have become the national standard during the Great Depression. Here’s the story of why that didn’t happen.

The nature of work has undergone a lot of changes during the coronavirus pandemic. Millions of office workers began working from home; the service industry has struggled to get workers to come back, and some businesses, like Kickstarter, are now experimenting with four-day workweeks — without reducing salaries. In Congress, Rep. Mark Takano (D-Calif.) has introduced legislation to make a 32-hour workweek standard.

This “great reassessment” of labor feels revolutionary. But we have been here before. In 1933, the Senate passed, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported, a bill to reduce the standard workweek to only 30 hours.

Americans have worked hard, perhaps too hard, since the Colonial era. English and other European colonists often had to work longer and harder on farms here than in the Old World, and a philosophy of working from sunrise to sunset prevailed, according to the Economic History Association. The Massachusetts colony even passed a law requiring a 10-hour minimum workday.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

Reconstruction Finance

Popular politics and reconstructing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

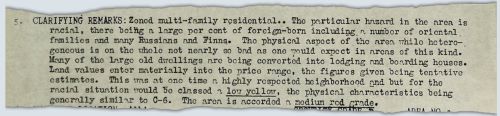

Like the world system as a whole, segregated cities in the United States have their own finance driven core-periphery dynamics. The world economy is structured by countries with competitive export sectors and trade surpluses, like Germany and China, who exhibit underconsumption and excess savings; the US’s debt-fueled economy receives these savings through its domination of global financial markets. The dynamic strengthens the power of global finance at the expense of wages and living standards. And within the US, the allocation of credit and investment has exacerbated racial disparities and altered the municipal geography of debt. At the level of the city and the financial system, these developments warrant a powerful political response. But what form can that response take?

Global underconsumption and a structurally-weakened working class are problems likely to persist as the twenty-first century marches on. Altering the shape of our global economy will require building new institutions capable of funneling excess savings into productive investment. This is not something that can be done with a temporary increase in spending—no matter how large. Moreover, as commentators stressed in the wake of the Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020, such investment must be democratically managed. Can the tensions and energies created on the local scale be harnessed to address larger macroeconomic imbalances? The history of the New Deal’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation offers a starting point with which to think through these dynamics.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PHENOMENAL WORLD

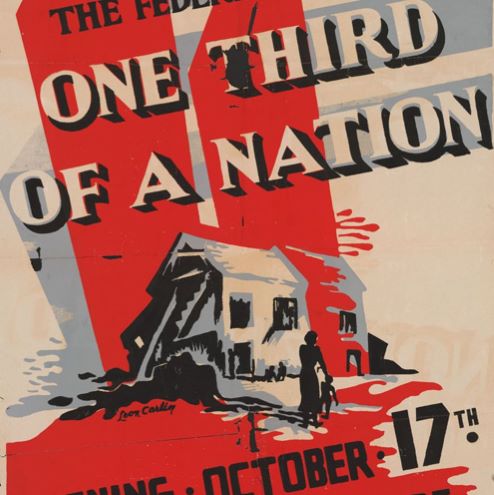

The New Deal Program that Sent Women to Summer Camp

About 8,500 women attended the camps inspired by the CCC and organized by Eleanor Roosevelt—but the “She-She-She” program was mocked and eventually abandoned.

During the Great Depression, thousands of unemployed men picked up saws and axes and headed to the woods to serve in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program that employed about 3 million men. But men in the CCC weren’t the only ones to take to the great outdoors on the New Deal’s dime. Between 1934 and 1937, thousands of women attended “She-She-She camps,” a short-lived group of camps designed to support women without jobs.

The program was the brainchild of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who wanted an option for the 2 million women who had lost work after the stock market crash of 1929. Like their male counterparts, they looked for work, but stigma against women who worked and women who took government aid made finding a job even more difficult. Many women were forced to seek dwindling private charity or turned to their families. Others became increasingly desperate, living on the streets.

Their plight deeply concerned Roosevelt, who wondered if they might be served by the CCC. The program, which sent men to camps around the country and put them to work doing forestry and conservation jobs, was considered a rousing success. But Roosevelt encountered resistance from her husband’s cabinet, which questioned the propriety of sending women to the woods to work.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HISTORY

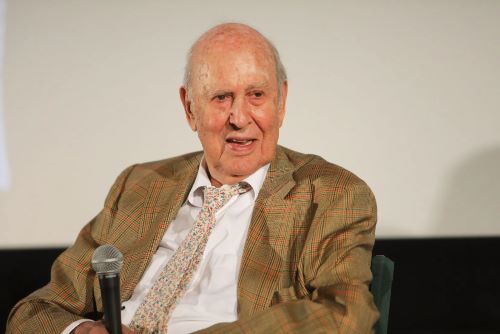

Carl Reiner’s Life Should Remind Us: If You Like Laughing, Thank FDR and the New Deal

Reiner, Stephen Colbert, Jordan Peele, Steve Carrell, Tina Fey, Julia Louis-Dreyfus: Their comedy descends directly from the Works Progress Administration.

When Carl Reiner was 17 in 1939, he was working as a machinist’s helper, bringing sewing machines to hat factories. Then Reiner’s brother saw a small ad in the New York Daily News about free acting lessons being offered in lower Manhattan by the Works Progress Administration. Reiner had never contemplated acting before in his life, but his brother insisted, so he went.

The WPA had been established several years prior to carry out public works projects during the Great Depression, with workers put directly on the government payroll, keeping the struggling economy afloat while also expanding the infrastructure of the U.S. Its initial outlays were huge — the gross domestic product equivalent of about $1.3 trillion today. The WPA paved roads, built bridges, and constructed Camp David and the Tennessee Valley Authority. But it went beyond these physical public works to enhance America’s human infrastructure via Federal Project Number One, which employed writers, musicians, and actors. The Federal Theatre Project, part of Federal Project Number One, funded live performances and acting classes — including the ones Carl Reiner attended.

“All the good things that have happened to me in my life I can trace to that two-inch newspaper item my brother handed to me,” Reiner explained. “Had Charlie not brought it to my attention, I might very well be writing anecdotes about my life as a machinist or, more likely, not be writing anything about anything.”

But Reiner’s life was just one small aspect of the WPA’s impact. A few years earlier in Chicago, a sociologist named Neva Boyd had begun working with immigrant children by teaching them dance, movement, and improvisational games. She soon brought this work to Hull House, a progressive “settlement house” — a central place where anyone regardless of age, class, or culture could go to learn, share, engage with art, express themselves, and grow.

Boyd viewed creativity and playfulness as essential for a democratic society. “Social living cannot be maintained on the basis of destructive ideologies — domination, hate, prejudice, greed and dishonesty,” she wrote in a famous essay. “Play involves social values, as does no other behavior. The spirit of play develops social adaptability, ethics, mental and emotional control, and imagination.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE INTERCEPT

Cities and States Need Aid — But Also Oversight

Federal funding during and after the New Deal ended up hurting cities because of who spent it and how.

Faced with staggering public health costs and cratering tax revenue as a result of the coronavirus, officials in both parties are demanding federal aid for state and local governments. Even Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), who called for allowing states to go bankrupt two weeks ago, has moderated his stance, conceding that aid is now “highly likely.”

Some proponents invoke Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal as a model for this aid, asserting that nationally financed public works programs and relief during the 1930s restored cities to fiscal health after the Great Depression. A new round of federal aid, they argue, might do the same today.

A closer look at the consequences of federal aid to local governments beginning with the New Deal, however, reveals a very different lesson: that without robust democratic oversight and wise management at the local level, federal aid can exacerbate the fiscal problems it was meant to solve.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

The New Deal’s Capitalist Lessons for Joe Biden

The most effective part of F.D.R.’s program wasn’t its direct spending. It was his use of U.S. financial might to reignite business.

In American politics, we talk a great deal about the New Deal, particularly in times of economic crisis. But our collective memory of its contents typically fails to include its most powerful parts.

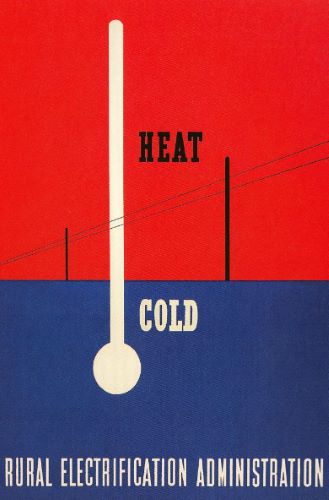

The New Deal’s alphabet soup of job programs still loom large, and was doubtlessly a saving grace for millions of working men and their families. However the macroeconomic impact of President Franklin Roosevelt’s direct government employment programs was dwarfed by what I call the “Other New Deal”: low-cost government loans, ambitious housing insurance programs and tax subsidies that spurred major industries. Together, this resurrected private investment and loosened credit markets — the heart of the capitalist system — for businesses and everyday people.

As President Biden begins his presidency with razor-thin Democratic congressional majorities that could stymie future spending plans, these undersold successes of the New Deal provide him with a historical blueprint for how to creatively “Build Back Better.”

Take the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, or R.F.C., which was led by Jesse Jones, the Texan lumberman, developer and banker. Jones held a dim view of Eastern bankers, who believed they had already invested in everything worth doing. This glut of savings — that is, idle capital — could not be profitably invested, or so the bankers thought. (Somewhat similarly, despite the stable economy of the past decade, we’ve witnessed a glut of private savings as financiers focus on speculation in property and stocks .)

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

A Stronger Welfare State Is the Key to Saving Democracy From Extremism

Democrats’ policies aim to address societal problems to make fascism and socialism less attractive.

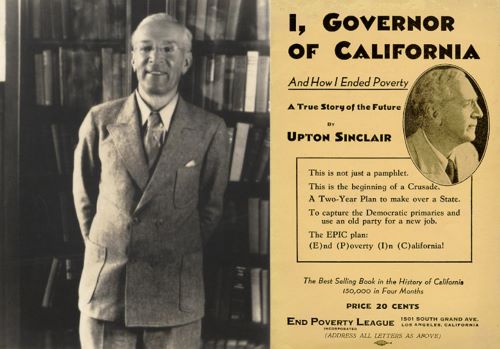

Republicans frequently charge that Democratic ideas are socialist or radical. But there is deep irony in these charges: Democrats are trying to grow and strengthen a social safety net that dates back to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. And far from being radical, the New Deal aimed to save the United States from the growing popular allure of undemocratic extremist philosophies such as Italian fascism. This history offers a blueprint for President Biden at another moment when undemocratic philosophies, specifically those tied to Donald Trump and his proteges, entice Americans.

During the 1920s, government became increasingly disconnected from the American people because of its inability to deal with the transition to an industrial economy. Rural Americans suffered the most, since mechanization on farms led to mounting debts and falling prices. Congress debated farm relief throughout the decade but couldn’t reach an agreement.

According to observers such as New York Times journalist Anne O’Hare McCormick, legislators’ lack of expertise was part of the problem. It left them floundering over complex issues such as subsidies and surpluses. This poor governance, in turn, made for apathetic citizens. Less than 50 percent of eligible voters had gone to the polls in 1920 and 1924 because Americans viewed elections as a spectator activity that lay outside “the class of major sporting events,” McCormick wrote.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

America’s Forgotten History Of Mexican-American ‘Repatriation’

During the Depression, more than a million people of Mexican descent were deported. Author Francisco Balderrama says that most were American citizens.

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Terry Gross. Donald Trump has proposed immigration reform that would include building a wall on the Mexican border, paid for by Mexico, and calls for the mass deportation of immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally. The deportation plan has echoes of a largely forgotten chapter of American history when, in the 1930s, during the Depression, about a million people were forced out of the U.S. across the border into Mexico. It wasn’t called deportation. It was euphemistically referred to as repatriation, returning people to their native country. But about 60 percent of the people in the Mexican repatriation drive were actually U.S. citizens of Mexican descent. Perhaps the most widely cited book on the subject was co-written by my guest, Francisco Balderrama. The book is called “Decade Of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation In The 1930s.” His late co-author, Raymond Rodriguez, had family that was forced out of the U.S. Balderrama is a professor of American history and Chicano studies at California State University, Los Angeles.

Francisco Balderrama, welcome to FRESH AIR. Would you give us an overview of the scope of the mass deportations or the repatriation of the 1930s? Like, how many people were affected? And of those people, how many of them were actually American citizens?

FRANCISCO BALDERRAMA: Well, conservatively, we’re talking about over 1 million Mexican nationals and American citizens of Mexican descent from throughout the United States, from the American Southwest to the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest to the South, even Alaska included. This occurred on a number of different levels through a formal deportation campaign at the federal government, then also efforts by major industries as well as efforts on the local and state level. Conservatively, we are able to estimate that 60 percent of them were U.S. citizens of Mexican descent.

GROSS: So what was behind these deportations? Was it the Depression?

BALDERRAMA: Well, the Depression set the scenario for what happened. I think one needs to keep in mind that in the American public at that time, Mexicans were targeted as a scapegoat partly because they are the most recent immigrant group to come to the United States in the early 20th century.

READ AND LISTEN AT FRESH AIR, NPR

The Dust Bowl

The Kept and the Killed

Of the 270,000 photos commissioned to document the Great Depression, more than a third were “killed.” Explore the hole-punched archive and the void at its center.

The first killed negative I encounter is of a field. It’s a Carl Mydans shot, and a drought has reduced the land to a flat, cracked expanse out of which only a few tenacious scraggles of crabgrass have managed to sprout. Nothing notable here, no action, no grand geometries — except that the center of the negative has been pierced by a perfect circle, as though in counterpoint to the sprocket holes running along the photo’s edge. Briefly I imagine that this circle is what has doomed the land, a well into which all the precious waters must have run. Months after coming across the photograph, it is that void, more than any peripheral scenery, which remains anchored in my memory — that and the caption describing the picture as “killed”.

Begun as part of the alphabet soup of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), under the aegis of which Mydans’ ill-fated photo was taken, had been tasked with resettling struggling farmers onto more fertile ground, providing education about agricultural science, and giving loans for the purchase of land, feed, and livestock. Arguably its most enduring legacy today, however, is the hundreds of thousands of photographs the agency produced to document the plight of destitute farmers, many of whom were trapped in an inescapable pit of debt made deeper still by the environmental devastation of the Dust Bowl. The project’s head, Roy Emerson Stryker (1893–1975), would shop his favorites around, going from newsroom to newsroom “with pictures under his arm”, as Dorothea Lange would later recall, in an attempt to secure placements in major papers. Stryker had encyclopedic ambitions: tasked with the mission of “introducing America to Americans”, the FSA’s photography wing would soon see its remit balloon far past images of rural poverty to encompass everything from aerial shots of utopian building projects to Kodachrome still lifes — all of which could find a home within what Stryker called simply the File.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE PUBLIC DOMAIN REVIEW

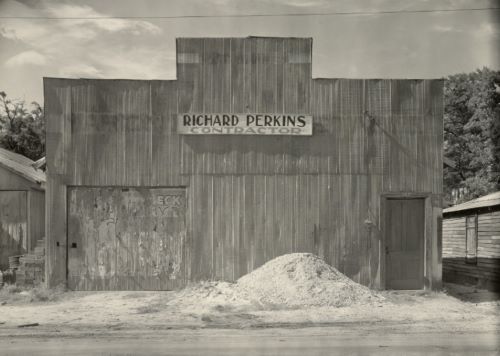

The Anti-Nostalgia of Walker Evans

A recent biography reveals the many contradictions of the photographer who fastidiously documented postwar American life.

In Starting From Scratch, art historian Svetlana Alpers’s biography of the American photographer Walker Evans, the images come first. All the classics are here: the iconic Great Depression–era portraits of white tenant farmers; the economic immiseration contrasting with natty, white-suited cool in his pictures from Cuba; the subway portraits surreptitiously taken using a hidden camera. They are joined with lesser-known works that index the interior and exterior architecture of an America that was already receding into history in Evans’s time. Dilapidated buildings and the tattered, upholstered violence of once glorious plantation homes are captured alongside so many wagons, statues, and show bills—an Americana that slept in its makeup the night before and looks fragile in the light of day. A corrugated tin facade, its variegated surface palimpsestic with faded ads, a pile of dirt out front. A frowning woman in a cloche hat and furs on a busy shopping street. A spiny succulent bursting out of a bucket marked “TRIPLE WHITE,” floral wallpaper, a tiny American flag.

First we see, then we read, and it feels right. Evans was the rare photographer who preferred publishing in print over being exhibited, and indeed he is best known for books like American Photographs (1938) and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), with its text by James Agee. “From the start,” Alpers explains, “Evans imagined seeing his photographs not in, but as a book, a book about America.” A 1933 letter by Evans is notable for the way it prefigures both these later volumes and a very contemporary understanding of the photographer as someone who selects images from the multimedia stream that surrounds us today, whether or not they took them themselves:

A wonderful volume is waiting to be done which would describe America, to ourselves as well as to strangers, entirely by means of pictures—photographs of America, machines, factories, and landscapes, portraits of American faces of low and high degree, intelligent selections from news photographs and the contents of the Sunday photo-gravures.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NATION

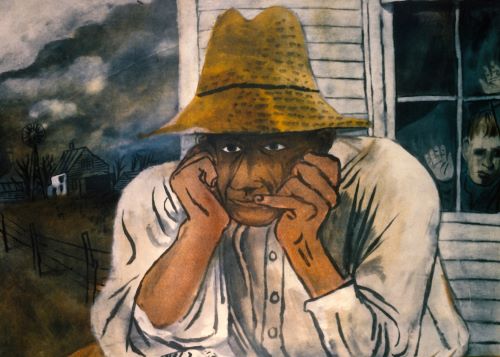

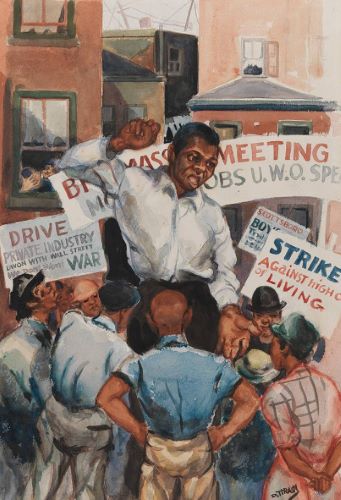

When Black and White Tenant Farmers Joined Together to Take on the Plantation South

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union was founded on the principle of interracial organizing.

It’s 1935 and class war is brewing in Arkansas. Standing before 1,500 black and white sharecroppers, the radical Methodist minister Ward Rodgers thunders, “I can lead a mob to lynch any planter in Poinsett County.” The crowd erupts with applause.

These white and black sharecroppers who worked, lived, and died amid the vestiges of the Southern plantation system were no strangers to terror. The night before, a group of planters and deputy sheriffs had attacked an adult education class taught by Rodgers. The landowner class, the banks, the police, and an offshoot of the Ku Klux Klan called the Nightriders had been engaged in a brutal crackdown on the workers of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union.

Not to be outdone, the youthful and slender Harry Leland Mitchell rose to the stage. H. L. Mitchell was a union organizer and cofounder of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU for short), one of the first interracial and most influential unions in the South. In the middle of the town square, Mitchell defended the Methodist minister, saying, “Ward Rodgers is staying at my house. If any bunch of sons of bitches with their heads in pillowcases come to my house, they are going to get the hell shot out of them.”

The STFU would grow to thirty-one thousand members across the South, challenging the Southern landowning class and the Jim Crow white supremacist order, and leaving an undeniable legacy for both the labor movement and the civil rights movement.

Mitchell borrowed the title of his autobiography Mean Things Happening in This Land from a song of the same name written by the poet, singer, and STFU member John Handcox, whose poetry is found throughout the book. Mean Things Happening in This Land is not just a recollection of fights won and lost, but a lively look at what democratic socialist Michael Harrington called the “grandeur of ordinary people.” The cinematic bravery of poor folks, black and white, facing down the planters and Nightriders is right there next to bawdy jokes, stories of bourbon-soaked nights, and common things.

Mean Things Happening in This Land is a book about the grand sweep of history, but it’s often interrupted by everyday life. Its characters are heroic, but not in a storybook way. They were ordinary people, and they wanted only what was necessary to live a happy ordinary life. What distinguished them was their courage in fighting for it.

The STFU is a model of the connection between social and economic justice as well as the crucial role community must play in sustaining workers’ movements taking on the rich and powerful. We’d do well to study the union today, and Mitchell’s autobiography is as good a place as any to start.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JACOBIN

A Blueprint From History for Tackling Homelessness

During the New Deal, the U.S. knew that economic recovery depended upon housing.

One of the most pressing issues facing the United States during the 2020s is the issue of homelessness. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the instability of the economy, and the changing nature of employment, more Americans now live in precarity than in the previous decade. In California, where an estimated 30% of the nation’s chronically unhoused live, totaling up to 171,500 individuals, a range of nonprofit and civic groups have worked with state officials to address the issue. For example, Urban Alchemy has launched experiments with “safe sleep villages”: tent communities that offer stable housing, food, and bathroom facilities.

Such a program builds on the same ideas launched nearly a century ago during the New Deal when the Farm Security Administration (FSA) sought to tackle acute homelessness during the Great Depression.

Of the New Deal-era initiatives that sought to uplift unemployed Americans from poverty, the Farm Security Administration experimented with several programs to provide migratory families with stable housing and education to help unhoused Americans get back on their feet. As one of the first federal programs to offer affordable housing to unhoused individuals on a national scale, the FSA’s efficient and effective programs provide a blueprint for policymakers today.

Whitewashing the Great Depression

How the preeminent photographic record of the period excluded people of color from the nation’s self-image.

In one sense, the lack of diversity in classic FSA photographs comes as little surprise: The country was roughly 90 percent white during the Depression, and the FSA represented Black people in proportion to their share of the population. Yet overall representation is surely only part of the story, given that the FSA was supposed to be chronicling hardship among farmworkers. During the Depression, Black Americans made up more than half of the country’s tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and farmworkers in the South. In 1932, when a quarter of white Americans were unemployed, half of Black Americans were. “In some Northern cities, whites called for African Americans to be fired from any jobs as long as there were whites out of work,” according to the Library of Congress’s website for teachers. And Black sharecroppers were often forced out of work by white ones. “No group was harder hit than African Americans.”

Yet we’ve come to imagine the Great Depression as largely a white tragedy. That isn’t because the FSA photographers focused only on white subjects. If you look at the roughly 175,000 negatives in the complete FSA/Office of War Information file, now at the Library of Congress, you’ll see that the photographers working for the FSA and for its predecessor, the Resettlement Administration, and its successor, the OWI, documented many people of color. Lee photographed poor Black people in Missouri, and Mexican pecan shellers in Texas. Evans photographed Black Americans out of work in Mississippi and Alabama. And Lange photographed Filipino lettuce pickers and Japanese truck farmers in California.

The most direct responsibility for the whitewashing seems to lie with the photographers’ boss, Roy Stryker, who was the chief of the FSA’s historical section from 1935 to 1941, and then of the OWI’s photography unit. Three new books that pursue three very different subjects in very distinctive ways—Walker Evans: Starting From Scratch, by Svetlana Alpers; Russell Lee: A Photographer’s Life and Legacy, by Mary Jane Appel; and Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, a Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog—all offer evidence that FSA photographers often tangled with Stryker over matters of race.

Stryker openly worried that too much racial honesty might sink his ship at the FSA. Part of his mission at the agency was to compile a complete pictorial record of all kinds of Americans, known as “The File.” The other part was to present to Congress a sympathetic portrayal of American suffering, “to document the problems of the Depression,” as one photographer recalled, “so that we could justify the New Deal legislation that was designed to alleviate them.”

Stryker, in other words, was a realist. And the reality was that Congress, which controlled the FSA’s funds, was dominated by Southern Democrats, who, as Appel writes in her Lee biography, were “interested in preserving the racial status quo.” Knowing this, Stryker and other FSA officials “were reluctant to lead the agency in a crusade against racial disparity.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself feared the Southern Democrats. Without their support, his New Deal programs had no hope of surviving. Thus, although FDR signed an order barring discrimination in the projects sponsored by his newly founded Works Progress Administration in 1935, Appel notes that he wouldn’t back “an anti-lynching campaign because he was afraid of losing his Southern Democratic base.” And when the Social Security Act was passed, also in 1935, agricultural and domestic workers (who were disproportionately Black) were excluded from its benefits.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE ATLANTIC

How Washington Bargained Away Rural America

Every five years, the farm bill brings together Democrats and Republicans. The result is the continued corporatization of agriculture.

A classic premise in American cinema is the buddy comedy, epitomized by films like Tommy Boy or Midnight Run. Two characters who can’t stand each other are thrown together by circumstance, forced to make a screwball pilgrimage across the country to finish a job. Hilarity ensues.

This same storyline infects our politics every five years when the farm bill comes up for reauthorization. Two parties at the brink of civil war are pressured to cooperate in order to deliver for their respective constituents. Congress’s version of this tumultuous road trip runs through both rural and urban America, uniting liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans. But the ultimate winner of this madcap romp is one of the country’s most infamous heels: Big Agriculture.

Despite its title, the farm bill, which is due for reauthorization this September, impacts more than just farmers. Over 80 percent of the allocated funds supports the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, one of the largest welfare programs and arguably the United States’ closest imitation of a Scandinavian social safety net. The fate of SNAP’s 42 million impoverished recipients is shackled to a baroque patchwork of agriculture subsidies that could rival any late-Soviet central-planning efforts.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE AMERICAN PROSPECT

Savoring Pie Town

Sixty-five years after Russell Lee photographed New Mexico homesteaders coping with the Depression, a Lee admirer visits the town for a fresh slice of life.

The name alone would make a stomach-growling man wish to get up and go there: PieTown. And then too, there are the old photographs—those moving gelatin-silver prints, and the equally beautiful ones made in Kodachrome color, six and a half decades ago, at the heel of the Depression, on the eve of a global war, by a gifted, itinerant, government, documentary photographer working on behalf of FDR’s New Deal. His name was Russell Lee. His Pie Town images—and there are something like 600 of them preserved in the archives of the Library of Congress—portrayed this little clot of high-mountain-desert New Mexico humanity in all of its redemptive, communal, hard-won glory. Many were published last year in Bound for Glory, Americain Color 1939-43. But let’s get back to pie for a minute.

“Is there a particular kind you like?” Peggy Rawl, coowner of PieTown’s Daily Pie Café, had asked sweetly on the phone, when I was still two-thirds of a continent away. There was clatter and much talk in the background. I’d forgotten about the time difference between the East Coast and the Southwest and had called at an inopportune hour: lunchtime on a Saturday. But the chief confectioner was willing to take time out to ask what my favorite pie was so that she could have one ready when I got there.

Having known about PieTown for many years, I was itching to go. You’ll find it on most maps, in west-central New Mexico, in CatronCounty. The way you get there is via U.S. 60. There’s almost no other way, unless you own a helicopter. Back when Russell Lee of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) went to Pie Town, U.S. 60—nowhere near as celebrated a highway as its more northerly New Mexico neighbor, Route 66, on which you got your kicks—called itself the “ocean to ocean” highway. Big stretches weren’t even paved. Late last summer, when I made the trek, the road was paved just fine, but it was still an extremely lonesome two lane ribbon of asphalt. We’ve long licked the idea of distance and remoteness in America, and yet there remain places and roads like PieTown and U.S. 60. They sit yet back beyond the moon, or at least they feel that way, and this, too, explains part of their beckoning.

When I saw my first road sign for PieTown outside a New Mexico town called Socorro (by New Mexico standards, Socorro would count as a city), I found myself getting cranky and strangely elevated. This was because I knew I still had more than an hour to go. It was the psychic power of pie, apparently. Again, I hadn’t planned things quite right—I’d left civilization, which is to say Albuquerque—without properly filling my stomach for the three-hour haul. I was muttering things like, They better damn well have some pie left when I get there. The billboard at Socorro, in bold letters, proclaimed: HOME COOKING ON THE GREAT DIVIDE. PIE TOWNUSA. I drove on with some real resolve.

Continental Divide: this is another aspect of PieTown’s strange gravitational pull, or so I have become convinced. People want to go see it, taste it, at least in part, because it sits right on the Continental Divide, at just under 8,000 feet. PieTown, on the Great Divide—it sounds like a Woody Guthrie lyric. Something there is in our atavistic frontier self that hankers to stand on a spot in America, an invisible demarcation line, where the waters start to run in different directions toward different oceans. Never mind that you’re never going to see much flowing water in PieTown. Water, or, more accurately, its lack, has much to do with PieTown’s history.

The place was built up, principally, by Dust Bowlers of the mid- and late 1930s. They were refugees from their busted dreams in Oklahoma and West Texas. A little cooperative, Thoreauvian dream of self-reliance flowered 70 and 80 years ago, on this red earth, amid these ponderosa pines and junipers and piñon and rattlesnakes. The town had been around as a settlement since at least the early 1920s, started, or so the legend goes, by a man named Norman who’d filed a mining claim and opened a general store and enjoyed baking pies, rolling his own dough, making them from scratch. He’d serve them to family and travelers. Mr. Norman’s pies were such a hit that everybody began calling the crossroads PieTown. Around 1927, the locals petitioned for a post office. The authorities were said to have wanted a more conventional name. The Pie Towners said it would be PieTown or no town.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

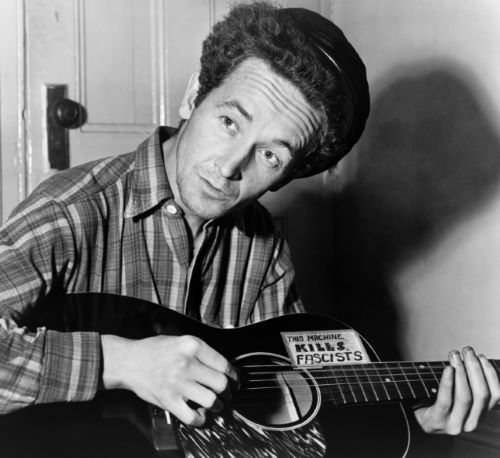

Government Song Women

The Resettlement Administration was one of the New Deal’s most radical, far-reaching, and highly criticized programs, and it lasted just two years.

It was October 1935, and the Resettlement Administration was in trouble. The experimental agency—“RA” in the New Deal lexicon—was tasked with moving those hardest hit by the Great Depression onto government-built homesteads, but their early efforts were undermined by discord among the new homesteaders—a mix of farmers whose land had failed, jobless urban workers willing to return to farming, and unemployed miners and other workers whose jobs had disappeared.

The Special Skills Division, which had been created as a service division to make furniture and print materials for the RA, was charged with helping to develop recreation programs and activities to alleviate social tensions on the new settlements. Clubs were set up and programs introduced. But after visiting four RA homesteads in Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, Special Skills staffer Katharine Kellock submitted a report warning that instead of a solution to the homesteads’ social problems, the clubs had become “hotbeds of discontent.” At meetings, unhappy participants steered the agenda toward “a serious contemplation of their economic problems which they had no power to solve.”

Kellock characterized this discontentment as “an emergency situation” that was tearing apart the communities that the RA had worked hard to build. So who did the government call on to rescue their faltering social experiment? “The Special Skills Division,” Kellock announced, “is sending in leaders of music.”

Explaining the rationale, she wrote, “In every one of these colonies project managers and educational supervisors told me of the desperate need for recreation to keep up morale and carry the homesteaders through the present pioneer period. Without exception, they regarded musical leadership for the adult homesteaders as the first important assistance that we could give.”

The RA’s newly formed music unit dispatched field representatives to teach rudimentary music classes, organize musical groups, and lead community singing and other social events. Music unit representatives also visited homesteads and surrounding communities to record folk songs, which were then incorporated into the group singing to help strengthen ties among the homesteaders. This focus on the “social use” of music was intertwined with a larger (and controversial) goal of the RA: to foster an ideological shift on the homesteads, away from rugged individualism to an emphasis on collective responsibility. Homes were built in close enough proximity to encourage cooperation and a move toward cooperative farming, and every homestead included a community hall to allow residents to gather informally.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HUMANITIES

The Value of Farmland: Rural Gentrification and the Movement to Stop Sprawl

Rapidly rising metropolitan land value can mean “striking gold” for some landowners while threatening the livelihood of others.

Rents are rapidly rising. Property values are skyrocketing. Real estate taxes are ever-increasing. Long-time owners are selling out and moving away. Newcomers express values and politics at odds with older residents. This sounds like a gentrifying urban neighborhood—but it was the situation in not-long-to-be-rural, mid-twentieth century Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

J. Warren Shelly, whose family began farming in Bucks County in the 1700s, worried that he would have to sell the 65-acre farm where he was born, because its real estate tax assessment was increased 900 percent in 1972. Yet, as he noted, “The land isn’t for sale, so the market value doesn’t mean anything to us.” He went on to observe “It’s a funny thing…A lot of people came here originally because they like the way it is out here, with the open spaces and green fields. Those are the same people who are taxing us out of existence.”

Shelly was one of many Bucks County farmers who found their lives upended as the demand for exurban estates and suburban tract homes transformed their rural townships and caused land prices to sharply appreciate. Some farmers happily sold their land and pocketed the windfall, which allowed them to comfortably retire from the hard work and financial uncertainty of farming. But other farmers found increased property values and the higher real estate taxes they produced problematic if they wanted to continue to farm or to live out their retirement years on land that had been in their family for generations.

While many of the new arrivals were sympathetic to the plight of neighboring farmers, the novelty of the problem and the glacial rate of change in state and local government policy resulted in many long-time residents being uprooted from their land. When programs were finally enacted to preserve prime farmland and agriculture, the new policies were implemented largely because farmers found allies in their exurban neighbors who valued the amenity that a farm landscape provided.

The history of suburbanization has largely been written in order to understand the experience and motivations of the people who moved from city to suburb. I am interested in the perspective of the farmers who were living in the rural areas to which suburbanization came. The legacies of conflicts over land, how it is regulated and taxed, and who can afford to live on it, continue to reverberate not just in cities, but at the rural-urban fringe.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE METROPOLE

Postal Banking is Making a Comeback. Here’s How to Ensure it Becomes a Reality.

Grass-roots pressure will be key to turning the idea into reality.

Last week, the joint task forces put together by former vice president Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) to heal the Democratic Party at the end of a bruising primary revealed their policy proposals.

Among the most compelling suggestions was to make bank accounts and payment services more accessible to middle- and low-income Americans by creating new consumer banking roles for the Federal Reserve System and Postal Service.

The task force’s endorsement of this change represents a homecoming for Democrats, pushing the party to the left and turning toward the economic ideas that Sanders has advocated throughout his career. But the history of this kind of banking policy reveals that only a concerted push from the grass roots will make it reality.

Although government banking represents a major departure from recent policy, the idea has ample precedent in American history. It rose to prominence during the Populist movement of the 1890s. As a counterweight to the inequality of the Gilded Age, Populists advocated offering bank accounts at local post offices, making direct federal loans to farmers and placing the supply of money and credit under the control of government officials.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

Down in Dyess

Johnny Cash’s life in a collectivist colony during the Great Depression.

My grandfather met Johnny Cash at the Illinois State Fair. After serving in the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II and then mining coal for a while, Grandpa Elmer became an Illinois conservation officer. In August 1965, four years before he died, Elmer was assigned to work the state fair. Johnny Cash played on the grandstand.

After the show, Cash got intoxicated and volatile. The state troopers wanted to make sure the beloved performer didn’t get into any trouble. My grandfather had a reputation as a calm man who could talk anyone down, so his law enforcement buddies asked him to help handle Cash. Elmer spent the night hanging out with Cash in the hotel. Whenever Cash tried to go out and raise hell in the streets of Springfield, Elmer told him firmly: “Now Johnny, you don’t want to be doing that.”

In the spring of 2000, Elmer’s widow—my Grandma Frances—lay dying in a state hospital. While my mother was at Frances’s bedside, I spent the afternoons walking around their hometown of Stonington, Illinois. Surrounded by corn fields, the town was a change of pace for a fifteen-year-old Philadelphia kid, but I felt a connection to the place where generations of my family had lived, back when it was a booming coal town. It was at a Stonington yard sale that I bought my first Cash record, the famous live album Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Fittingly, the album included a cover of Merle Travis’s “Dark as a Dungeon,” which describes coal mines where “the sun never shines.” The song provided a glimpse into the life of my grandfather and other men in my family.

Johnny Cash’s own hometown is mentioned at the end of Folsom Prison, as an announcer introduces his father: “He used to be, many years ago, a badland farmer down in Dyess, Arkansas, but he’s Johnny Cash’s daddy, Mr. Ray Cash.” Johnny’s childhood in Dyess has long been central to his mythos. Cash detailed in his 1997 autobiography how he worked in the family’s fields from the age of five; at eight, he graduated from carrying water to picking cotton.1 This experience is dramatized in the 2005 biopic Walk the Line. Cash also writes about family cotton farming in songs like “Picking Time” and “Cotton Pickin’ Hands.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT CONTINGENT MAGAZINE

Documenting the Depression

The Enduring Lessons of a New Deal Writers Project

The case for a Federal Writers’ Project 2.0.

In 1937, Sterling A. Brown, a poet and literature professor at Howard University, published a forthright essay charting the history of Black life in his hometown of Washington, DC—from the district’s early status as the “very seat and center” of the domestic slave trade through the present-day effects of disenfranchisement and segregation. “In this border city, southern in so many respects, there is a denial of democracy, at times hypocritical and at times flagrant,” Brown wrote. “Social compulsion forces many who would naturally be on the side of civic fairness into hopelessness and indifference.”

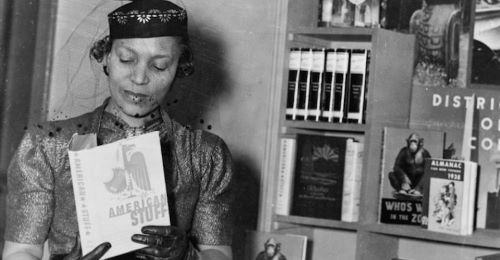

The essay was not the sort of thing you might have expected to find in a guidebook—let alone one paid for and published by the federal government—yet that’s exactly where it appeared: as a chapter in Washington, City and Capital, an early publication of a New Deal program known as the Federal Writers’ Project. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration founded the project two years earlier under the aegis of its Works Progress Administration, a relief program now best known for putting unemployed Americans to work building roads and bridges, but which also hired writers, actors, artists, and musicians—supporting creative labor while also launching programs in arts education, documentation, and performance. The guidebook—which was compiled as a template, of sorts, for similar works across the country—was hardly practical. It ran to more than a thousand pages; upon receiving a copy, Roosevelt reportedly quipped, “And where is the steamer trunk that goes with it?” But the reviews were positive.

At its peak, the Writers’ Project employed more than six thousand people. Some of its hires—Zora Neale Hurston, John Cheever, Richard Wright, Saul Bellow, and Studs Terkel, among others—were celebrated, or would become so, but most qualified by dint of their economic circumstances. The result was an eclectic staff—“a mazy mass,” as Time magazine put it, of “unemployed newspapermen, poets, graduates of schools of journalism who had never had jobs, authors of unpublished novels, high-school teachers, people who had always wanted to write,” and so on. Putting writers on the public payroll was controversial, but as Harry Hopkins, the administrator of the Works Progress Administration, said at the time, “Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT COLUMBIA JOURNALISM REVIEW

Photogrammar

A web-based visualization platform for exploring the 170,000 photos taken by U.S. government agencies during the Great Depression.

The 170,000 photographs taken between 1935 and 1944 under the direction of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and the Office of War Information (OWI) constitutes one of the richest photographic archives in the United States, arguably the world. One of the most famous documentary photography collections of the twentieth century, the “Historic Section” created visual evidence of government initiatives alongside scenes of everyday life during the Great Depression and World War II across the United States. Photogrammar provides tools to explore this abundant archive: maps to see photos taken in thousands of locations across the United States, a “treemap” to explore them categorically and thematically, a timeline to concentrate on a given moment in time or a specific photographer, and individual photographer pages with oral histories.

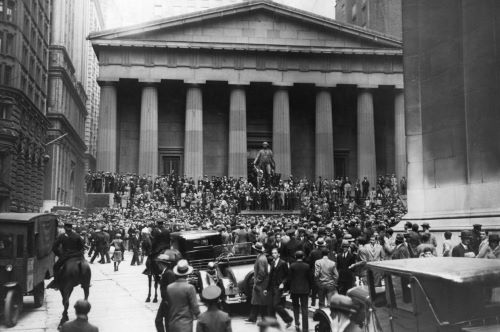

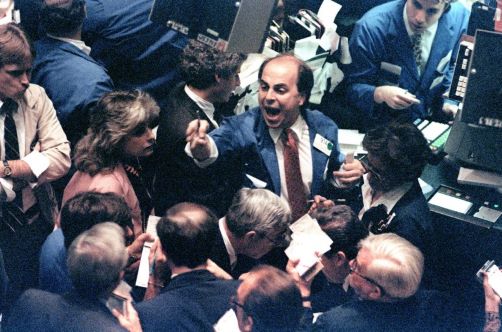

October 29, 1929, more infamously known as Black Tuesday, exacerbated a crisis that would become one of the most dramatic economic downturns in American history: the Great Depression. Millions of Americans were unemployed or underemployed as banks failed and market demand for products plummeted. Confidence in the very foundations of capitalism and government also quickly evaporated. By 1933, over 15 million Americans were unemployed. With the election of Franklin Roosevelt came a shift in policy from the Hoover years. The government focused first on relief followed by recovery and then reform. The set of programs that became known as the first New Deal created over thirty agencies and an extraordinary expansion of the federal government. Among the agencies was the Resettlement Administration (RA), which was established in May 1935 to relocate struggling families to planned communities. The RA came under immediate scrutiny. Looking to persuade the public about the value of their work, agency chief Rexford Tugwell created the Historic Section of the Resettlement Administration and hired Roy Stryker to lead the unit. The section would quickly become one of the most important documentary projects of the twentieth century.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT AMERICAN PANORAMA

Things as They Are

Dorothea Lange created a vast archive of the twentieth century’s crises in America. For years her work was censored, misused, impounded, or simply rejected.

In 1966 the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective devoted to Dorothea Lange—its first-ever solo exhibition of work by a female photographer. Lange’s photographs have now become part of our collective memory of the Great Depression. Migrant Mother (1936)—a portrait taken in a pea pickers’ camp in California of a woman holding her baby and surrounded by her children—is perhaps one of the most reprinted images in history. But beyond her better-known photographs of the Depression and the Dust Bowl migrations, Lange produced a vast archive of events and crises in the American twentieth century, from the Japanese internment camps to the arrival of the first Mexican braceros and the racial and economic inequality in the judicial system. Many of those photographs were censored by the US government for decades, or simply not published by the magazines that had originally commissioned them.

When John Szarkowski, head of MoMA’s Department of Photography, initially approached her in the early 1960s, Lange was almost seventy years old and suffering from cancer of the esophagus. She had already decided to devote the time she had left to making a series of intimate family portraits, and she agreed to the retrospective with some reluctance. There is film footage of Lange talking to one of her sons in 1963, as she’s looking over a lifetime of work for the exhibition and finding herself at an impasse. Her son tells her she just needs to get the job done, to stop doubting herself and hurry up. After a short pause, she responds: “It is not really modesty on my part. Don’t mistake it. It’s not modesty. It’s that I’m afraid.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK REVIEW

Layered Lives

Rhetoric and representation in the Southern Life History Project.

The Southern Life History Project, a Federal Writers’ Project initiative, put unemployed writers to work during the Great Depression by capturing the stories of everyday people across the Southeast through a new form of social documentation called “life histories.”

Layered Lives recovers the history of the Southern Life History Project (SLHP) through an interdisciplinary approach that combines close readings of archival material with computational methods that analyze the collection at scale. The authors grapple with the challenges of what counts as social knowledge, how to accurately represent social conditions, who could produce such knowledge, and who is and is not represented. Embedded within such debates are also struggles over what counts as data, evidence, and ways of knowing. As we look to our current moment, where debates about the opportunities and limits of quantification and the nature of data continue, the problems and promises that shaped the SLHP still shape how we capture and share stories today.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAYERED LIVES, STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

How Did Artists Survive the First Great Depression?

What is the role of artists in a crisis?

This year the questions come up again with a vengeance: What is the role of artists in a crisis? Writers ask, what does my work mean in this larger emergency? Does my personal creativity matter in the vast public sphere? And most immediately, how do I navigate this meltdown?

When the economy collapsed in 1929, American jobs disappeared at the rate of 20,000 a day. That used to impress people before this pandemic. In the Great Depression, the publishing and arts sectors shrank by about a third, like they have again recently. Creatives were desperate. Then, as now, there was private desperation and there was public desperation.

Harry Hopkins, the New Deal’s jobs program coordinator, focused on the public aspect and short-term solutions. When Congress questioned the idea of supporting artists and writers with jobs in the Works Progress Administration, Hopkins replied that artists had to eat like everyone else. In response to protests in New York by unemployed publishing workers who felt abandoned, the WPA began a small Federal Writers’ Project and others for art, music, and theater. The notion behind “work relief” was that paying work could sustain morale better than direct unemployment payments.

Researching a handful of WPA writers and artists for a book and documentary, I was struck by the variety of their personalities and responses. I found myself examining their choices for clues to getting through our own time. Some were already mature artists, like Zora Neale Hurston, Anzia Yezierska, and Dorothea Lange (who ran a portrait studio in San Francisco for over a decade). Others were fresh out of college like May Swenson, Saul Bellow, and Margaret Walker. Some we may not associate with the 1930s, like Ralph Ellison and Kenneth Rexroth, who for most people remains tied to the Beat poets, though he resented the comparison.

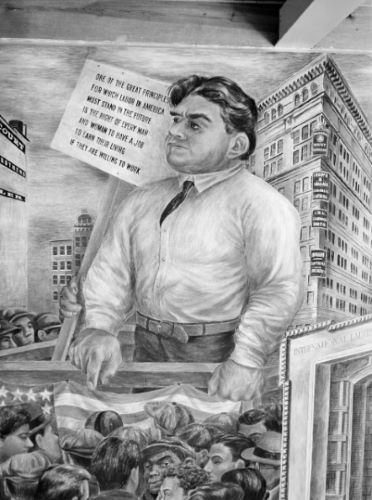

Back then there was even less agreement on a public role for creatives. The Writers’ Project assigned them a public role in producing travel guidebooks, histories, and life stories of everyday Americans, including thousands of narratives of formerly enslaved people. New Deal artists created landscapes, murals, street scenes, portraits, sculptures, and abstracts inspired by American life.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LITERARY HUB

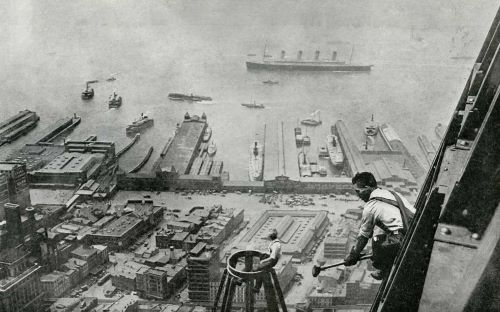

One of the Most Iconic Photos of American Workers is Not What it Seems

But “Lunch atop a Skyscraper,” which was taken during the Great Depression, has come to represent the country’s resilience, especially on Labor Day.

Eleven pairs of shoes were dangling over the New York City skyline. It was September of 1932, as the Great Depression was reaching its height. Unemployment and uncertainty could be felt throughout the city and the entire country. But on West 49th Street, a pillar of hope was under construction: the art deco skyscraper that would come to be known as 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

The ironworkers constructing its 70 floors were taking a break, sharing boxed lunches and cigarettes. They appeared to be completely unfazed by the location of this break: a narrow steel beam jutting out into the sky, hundreds of feet above the pavement.

As one coveralled man helped another light his smoke, someone snapped a picture. The resulting photograph became one of the most iconic images in the world, an embodiment of the spirit of the American worker. It still hangs in pubs, classrooms and union offices across the nation. Construction workers frequently re-create the 87-year-old photo. And every Labor Day, it is shared across social media, in tribute to those whose perspiration and determination built this country.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

The Making of an Iconic Photograph: Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother

The complex backstory of one of the most famous images of the Great Depression.

At the end of a long day in March 1936, Dorothea Lange stopped in a migrant workers camp in California for just 10 minutes and took six photos of a woman and her children. The final photo, known as Migrant Mother, became one of the most iconic photographs of the Great Depression.

In this video, Evan Puschak details not only the context the photo was created under (FDR’s administration wanted photos that would shift public support towards providing government aid) but also how Lange stage-managed the scene to get the shot she wanted.

As Puschak notes, the photo we are all familiar with was retouched three years after its initial publication to remove what Lange saw as a detriment to the balance of the scene: the thumb of the woman’s hand holding the tent post in the lower right-hand corner.

The Haunting of Drums and Shadows

On the stories and landscapes the Federal Writers’ Project left unexplored.

Savannah is haunted. That’s the first thing tourists learn about this city at the northern end of Georgia’s hundred-mile coast—a notion solidified in the popular imagination by the success of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, both the 1994 book by John Berendt and the subsequent film directed by Clint Eastwood. Midnight revolves around a nouveau riche antiques dealer named Jim Williams. Berendt, formerly the editor of New York magazine, happened to be in Savannah in the early 1980s when Williams killed a roughneck rent boy; he chronicled the event’s reverberations through Savannah society, which he depicts as eccentric and decadent. “The whole of Savannah is an oasis,” an informant tells him. “We are isolated. Gloriously isolated!”

“I suspected that in Savannah I had stumbled on a rare vestige of the Old South,” Berendt concludes. This vestige isn’t exactly the plantation fantasy—for Berendt, the Old South seems to have something to do with an enduring, atavistic faith in certain habits and creeds. The white elite believe in social custom; they have their teas and luncheons. Williams, bred in small-town Georgia, is able to insinuate himself into this echelon, but he maintains connections to other worlds, too. Williams buttresses his defense with an extralegal approach: he engages the services of a black root worker named Minerva. (Related to hoodoo, root work is a West African–derived form of folk medicine or magic practiced in the South.) Williams explains to Berendt that Minerva had been the “common-law wife of Dr. Buzzard,” a famous voodoo practitioner. One of Dr. Buzzard’s specialties was in the legal realm, where he “was especially effective ‘defending’ clients in criminal cases. He’d sit in the courtroom and glare at hostile witnesses as he chewed the root.” After Dr. Buzzard died, Minerva continued his work both in and out of the courtroom. A central scene in the book is set in a cemetery: the midnight garden of the book’s title, where Minerva has Williams drop “nine shiny dimes” into the dirt while she communicates with his victim, whom she tries to persuade to “ease off a little.”

In some ways it was a familiar scene, and the notion of the southeast coast’s being “gloriously isolated” was not a novel proposition. Earlier in the century, a similar spirit undergirded another spooky book, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, a peculiar volume compiled in the 1930s by workers affiliated with the Federal Writers’ Project’s Savannah Unit. Other FWP workers in the South gathered oral histories of slavery; the Savannah Unit, under the leadership of a white woman named Mary Granger, embarked on a stranger and far more fraught mission. Inspired by the anthropologist Melville Herskovits, Granger believed the lack of outside influence had led black people to retain certain “African” cultural traits or “survivals.” Her idea of what these attributes were is expressed in the book’s title and in her introduction, which mentions “sorcery,” “root doctors,” “miracles and cures,” and “mystic rites.” One such rite would be familiar to Berendt’s readers: “Not very long ago when a man was arrested for murder,” Granger wrote, “his friends, wishing to save him, went to the grave of the murdered man, secured some dirt, and left three pennies on the grave.”

Who’s to say what did the trick, but Jim Williams was eventually acquitted, following his fourth trial. Midnight became a juggernaut, credited with boosting Savannah’s tourism industry while earning it a reputation as uniquely spooky—the U.S.’s “most haunted” city, according to a 2002 designation by the American Institute of Parapsychology (an honor conceded to be “more honorary than scientific”). The Minerva scenes were more or less tangential to the book’s action. Combined with the fact of the murder itself, the strange social scene surrounding it, and the city’s gruesome preexisting history (slavery, several nineteenth-century yellow fever epidemics), they nonetheless seemed to suggest a place imbued to its bones with the macabre—a place where the dead were unusually close at hand. In 2007 the scholar Glenn W. Gentry credited the book with sparking a “boom in Savannah’s ghost tourism trade,” which hasn’t really flagged. Visitors still tour the city in repurposed hearses, walk through colonial and antebellum cemeteries, and pay for admission into purportedly haunted mansions lining Savannah’s famous squares.

Published in 1940, Drums and Shadows was nowhere near as successful as Midnight, but its impact was at least as profound: if Berendt’s book helped shape Savannah’s reputation in the 1990s and beyond, Drums and Shadows did similar work for the whole of the Georgia coast a half century before.1

It continues to be a valuable source for historians, folklorists, the descendants of enslaved people, novelists, artists, and many others, though it was always a plainly fraught endeavor. If white writers traveling the American South in the 1930s in pursuit of what they perceived to be the most “exotic” aspects of people then living under the violent terror of Jim Crow sounds like an ethical and methodological train wreck—well, it is.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAPHAM’S QUARTERLY

Solidarity Now

An experiment in oral history of the present.

There are times when, as if by some mysterious alchemical process, mere ink and printed typeface can bring an actual human existence to life, and a person’s voice seems to rise, almost audibly, from the page. In this case, the voice belongs to a Black woman named Emma Tiller who lived in West Texas in the 1930s and worked as a cook for some of the better-off white folks. She and her husband had previously been sharecroppers, and she is speaking of her solidarity with other poor people.

“When tramps and hoboes would come to their door for food, the southern white people would drive them away,” she recalls. Many of these homeless men were white, yet Tiller remembers that when a Black person came to the door, her white employers would offer food and sometimes money. “They was always nice in a nasty way to Negroes,” Tiller observes. And so she and other domestics went out of their way to help the white men who were driven off.

When the Negro woman would say, “Miz So-and-So, we got some cold food in the kitchen left from lunch. Why don’t you give it to ’im?” she’ll say, “Oh, no, don’t give ’im nothin’. He’ll be back tomorrow with a gang of ’em. He ought to get a job and work.” . . . Sometimes we would hurry down the alley and holler at ’im: “Hey, mister, come here!” And we’d say, “Come back by after a while and I’ll put some food in a bag.” . . . Regardless of whether it was Negro or white, we would give to ’em.

Tiller’s words were recorded and quoted, along with those of more than 150 others who lived through those years, by Studs Terkel in his 1970 oral history of the Great Depression, Hard Times. It’s a period that’s been much on my mind this past year, as Americans have suffered mass unemployment and social upheaval on a scale not experienced since the thirties—a time when the American system appeared on the brink, and a wave of radicalism, of desperate people and emboldened social movements, rose to meet the moment.

There are plenty of political and economic histories of the period, but they tend to lose sight of the daily realities of lived experience. Which may be why, last spring, when life as we knew it fell off a cliff—when our converging catastrophes, political and planetary, were overtaken by the coronavirus pandemic—I became preoccupied with what it was really like to survive through that earlier decade of crisis, how it was that people and communities and movements held together or came apart under extreme conditions. And so I reached for Terkel’s book and other such documents, and I was reminded of the great value, especially in a theory-heavy time, of oral history as a form: its testimony to the unavoidable and not always convenient fact that history and politics, economic forces and mass movements, are driven not simply by ideological and demographic abstractions but by individual, living-breathing human beings.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE BAFFLER

Lewis Hine, Photographer of the American Working Class

Lewis Hine captured the misery, dignity, and occasional bursts of solidarity within US working-class life in the early twentieth century.

Late in his career, labor photographer Lewis Wickes Hine used his camera to capture the best of working life in the United States. As the New Deal ushered in job opportunities and social welfare programs for a large swath of the American population, he documented the country’s gradual recovery from the Depression. Photographs of a Works Progress Administration (WPA) childcare center mark a progression from his famous child labor photographs three decades earlier.

While he lived long enough to see robust federal aid that empowered laborers, Hine is best known for work that challenged capitalist exploitation in the workplace. Driven by his belief that labor was the soul of America, he attributed the nation’s achievements to the individual men, women, and children who made them possible.

Hine’s lifetime roughly paralleled the Second Industrial Revolution, from 1874 to 1940. The era’s increasing speeds of manufacturing stretched the physical limits of manual labor, while photography as a medium evolved from a surveillance tool to a method of exposure. As an investigative photographer, Hine chronicled the normalized labor abuses in US factories leading up to the Great Depression. Not only did he help introduce some of the country’s first child labor laws, he also revolutionized photography’s artistic use value.

Hine once argued that a good picture is “a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others.” For him, an organized workforce was the epitome of empathy and mutual benefit, which he hoped to convey to the greater American public.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JACOBIN

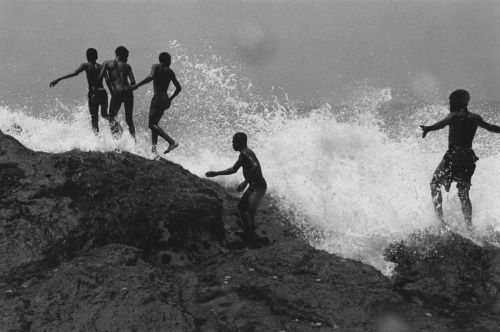

Chester Higgins’s Life in Pictures

All along the way, his eye is trained on moments of calm, locating an inherent grace, style, and sublime beauty in the Black everyday.

When Higgins began making photographs for magazines and newspapers, in the late nineteen-sixties, he was one of a handful of Black photographers working in mainstream media. Much of the work produced in his thirty-nine years as a staff photographer at the Times was a concerted attempt to incorporate Black America into the world’s consciousness. “When I arrived at The New York Times in 1975, I felt the media was immune to any real comprehension of the world I knew well,” he wrote at the time of his retirement from the paper, in 2014. “I wanted to share the history and traditions of the people I grew up with.”

Higgins grew up in New Brockton, Alabama, where, as a nine-year-old, he first encountered the spirit in his bedroom. He recalls waking in the middle of the night to a vision of a Black man in ancient clothing; the figure meditated, and then began to move toward him. “It said, ‘I come for you,’ ” Higgins told me, “and I screamed.” His elders understood the sighting as a call to faith, and he spent the following years preaching to congregations around his county as a youth minister.

It wasn’t until Higgins matriculated at the Tuskegee Institute, however, that he found his true vocation. He was studying business management and handling the budget for the campus newspaper. One semester, the paper was over budget, so Higgins had the idea of selling large photographic advertisements to local businesses to fill the gap. He commissioned P. H. Polk, Tuskegee’s official university photographer—and the only person Higgins knew with a camera—to take them.

Come press time, the pictures had yet to materialize, so Higgins went to Polk’s studio to track them down. He noticed old photographs that Polk had made during the Depression, portraits of Black farmers. Polk had lived on a busy road, a route where country folk would walk or drive mule-drawn wagons to sell their harvest at the weekend market. Every time a character caught Polk’s eye, he would hop off his porch and offer them five dollars to come pose for portraits inside his home studio. These images were revelatory for Higgins. In them, not only did he recognize people that could have easily been his “great aunts and uncles” but he also was struck by a certain stately quality in the treatment of the photo’s subjects.

“Nowhere were the elements of decency, dignity and virtuous character recorded in photographs of African Americans,” Higgins wrote in his 2004 photo-memoir, “Echo of the Spirit.” While he was growing up in southeast Alabama, in the fifties and sixties, the images of Black people in popular media that Higgins encountered were often of a particular bend; he disliked that “we were always seen as potential thugs or rapists.” And, back then, Higgins conceived of photography as a procedural craft rather than an artistic one. “It wasn’t tracing your emotions,” he told me. “It was objectifying something that had happened, some event, some cause.” It was only through his visit to Polk’s studio, and the marvel of those dignified portraits, that he began to realize the expressive—and corrective—potential of photography. The camera, he found, could be a vehicle for conveying the poise and esteem that emanated from the people around him and animated much of his early life.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORKER

How Eudora Welty’s Photography Captured My Grandmother’s History

Natasha Trethewey on experiencing a past not our own.

I was given my first copy of Eudora Welty’s Photographs in 1990, not long after the book’s initial publication. Back then I was in my first year of graduate school, having committed myself to becoming a writer. Of course, I had found my way to Welty before that—through her stories and her illuminating meditation on the origins of her work in One Writer’s Beginnings. As a native Mississippian, I was drawn to this remarkable woman as much for the clarity and vision and truth of her fiction as for the history we shared—rooted in place—the fate of our geography.

“Place,” she wrote, “geography and climate shapes characters. . . . It furnishes the economic background [a writer] grows up in, and the folkways and the stories that come down to him in his family. It is the fountainhead of [her] knowledge and experience.” Looking at her photographs, I found the documentary evidence: the truth not only of her imagination but also of her experience, her deep observation, a record of what she had seen.

This was transformative for me. Already, I had begun writing notes in my journal for poems about my maternal grandmother, a black woman born in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1916, who’d come of age in the 1930s. As long as I can remember I had been listening to the stories about her life, her journeys, the work she’d done to survive, the work she loved, her faith and endless striving. I listened trying to see the palimpsest of her world overlaid on my own, the Mississippi I’d entered in 1966, 50 years after her, on the heels of major advancements in the civil rights movement—the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and ’65.

READ ENTIR ARTICLE AT LITERARY HUB

Shelter in Place

How the misery of homelessness continues to be compounded in America’s cities.

A Dust Bowl migrant may be the figure who most Americans would imagine when they think of Depression-era homelessness, and Dorothea Lange’s 1936 portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, sometimes called Migrant Mother, is easily the most famous depiction. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, came across Thompson in Nipomo, California, where the latter was a 32-year-old migrant farmworker, traveling with her seven children to wherever she could find work. The images Lange shot were used to illustrate a wire-service story about hungry workers in the frost-ravaged pea fields. Roy Stryker, head of the FSA photo unit, declared the photograph to be the “ultimate” image produced by his organization.

But Migrant Mother’s iconic status could overshadow the fact that homelessness was also a major problem in American cities during the Depression, both for locals and for the unemployed people from out of town who had hoped to find relief in industrial centers. It’s difficult to determine exactly how many city-dwellers were homeless, but a national survey from 1933 estimated the number at 1.5 million people, half of whom were transients without a permanent address in any state.

Most homeless people were unskilled laborers, but factory workers and domestic employees were also vulnerable to losing their jobs, and their homes. Perhaps most alarming to the American imagination was the plight of the white-collar workers—those who had seemingly achieved a level of security that should have kept them from the bread lines, but found themselves on the streets. Housing relief favored families, so many of the homeless were singles, or “unattached.”

Cities were overwhelmed by the newly homeless masses. In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, and the federal government stepped in to help with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which devoted an initial fund of $500 million to relief efforts. This included the Federal Transient Program, which helped create a network of shelters around the United States for the homeless, many of whom were barred from receiving assistance from municipalities because they could not prove they once had a local address. Warehouses, offices, stores, garages, schoolhouses, and hotels were converted to homeless lodgings. Separate from these efforts, some people congregated in shanty towns that came to be called “Hoovervilles,” after the president on whom many blamed for their misfortune. One of the largest, in Seattle, sprawled over nine acres of public land and housed up to 1,200 people. Hoovervilles clustered around every major city in New York during the Great Depression; from 1931 to 1933, a Hooverville occupied what is now Central Park’s Great Lawn.

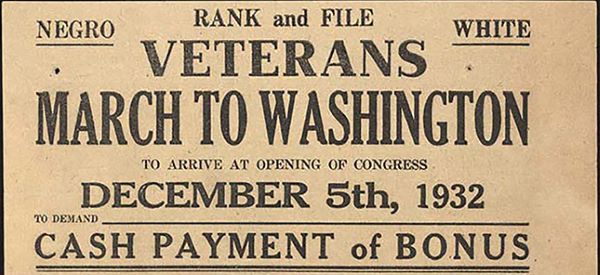

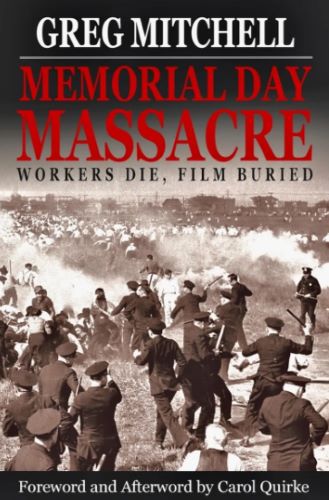

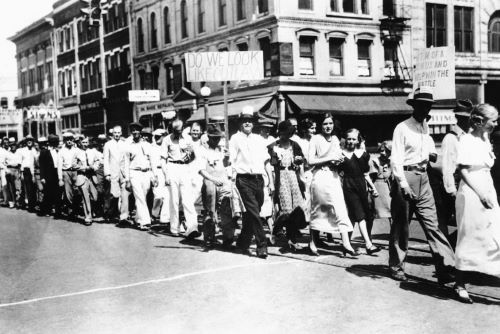

March of the Bonus Army

In 1932, twenty-thousand unemployed WWI veterans descended on Washington, DC to demand better treatment from the federal government.

In the summer of 1932, a group of World War I veterans in Portland, Oregon hopped a freight train and started riding the rails to Washington DC. They were demanding immediate payment of a cash bonus the government had promised them after the war – but delayed until 1945. Desperate for relief in the worst year of the Depression, the vets wanted their bonuses now. They called themselves the Bonus Army.

As they traveled east, veterans from all over the country joined up. By July, more than 20,000 veterans and their families had arrived in the nation’s capital. They established a tent city and vowed to stay until their demands were met. But finally, in a historic confrontation, General Douglas MacArthur’s Army troops routed the Bonus Army and burned their camp to the ground.

The Rise and Fall of New York Public Housing: An Oral History

New York City public housing has become synonymous with dilapidated living conditions. But it wasn’t always like this.

No heat. Leaking roofs. Mold and pests. Interminable waits for basic repairs.